Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

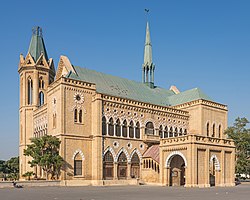

Frere Hall

View on Wikipedia

Frere Hall (Urdu: فریئر ہال) is a building in Karachi, Pakistan that dates from the early British colonial era in Sindh. Completed in 1865, Frere Hall was originally intended to serve as Karachi's town hall,[1] and now serves as an exhibition space and library.

Key Information

Location

[edit]Frere Hall is located in central Karachi's colonial-era Saddar Town, in the Civil Lines neighborhood that is home to several consulates.[2] The hall is located between Abdullah Haroon Road (formerly Victoria Road) and Fatima Jinnah Road (formerly Bonus Road). It lies adjacent to the colonial-era Sind Club.[3]

History

[edit]The building was intended to serve as Karachi's town hall, and was designed by Henry Saint Clair Wilkins,[1] who was chosen from among 12 candidates.[4]

The building's land was purchased at a cost of 2,000 British Indian rupees,[1] which had been donated by WP Andrew of the Scinde Railway, and Sir Frederick Arthur Bartholomew.[1] The total cost of the Hall was about 180,000 rupees, out of which the Government contributed 10,000 rupees, while the rest was paid for by Karachi municipality.[5]

Work commenced in August 1863 and continued until October 1865;[6] construction had not been entirely completed by the time of its inauguration.[4]

In 1877 at Frere Hall, the first attempt was made to form a consistent set of rules of badminton.[7] Following the death of Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere in 1884, the building was renamed in his honour.[8] Frere was a British administrator who was known for promoting economic development in Sindh, as well as for making the Sindhi language the language of administration in Sindh, rather than the Persian language, which had been favoured by the Mughals.

Following the independence of Pakistan, the hall's library was renamed as Liaquat National Library. The library is one of Karachi's largest, and houses a collection of more than 70,000 books, including rare and hand-written manuscripts.[3]

The hall's ceilings were decorated by the world-renowned Pakistani artist Sadequain in the 1980s, with one mural remaining incomplete after his death in 1987.[9] Several other works by Sadequain are found in the hall, and form what is known as the "Galerie Sadequain".[3]

The hall was closed periodically between 2002 and 2011 due to numerous attempted terrorist attacks on the nearby US consulate,[8] and was not reopened permanently until 2011 when the consulate was relocated to a site further away. It is now directly administered by the Karachi Municipal Corporation, and hosts several festivals.[10]

Architecture

[edit]

Frere Hall was built in the Venetian-Gothic style that also blends elements of British and local architecture. The building features multiple pointed arches, ribbed vaults, quatrefoils, and flying buttresses. Carving on the walls and beautifully articulated mosaic designs are visible on multiple walls and pillars.[3][8]

The building is built primarily out of local yellow-toned limestone,[3] with stone details formed from white oolite stone quarried from the nearby town of Bholari.[4] Red and grey sandstone is also used in the building, which was quarried from the Sindhi town of Jungshahi.[4]

A tall octagonal tower is located in one of the building's corner that is crowned by an iron cage.[4] The roof of the hall is coated with Muntz metal.[4]

The hall is surrounded by two lawns originally known as "Queen's Lawn" and "King's Lawn" which after independence were renamed as Bagh-e-Jinnah, or "Jinnah Gardens".[3]

Exhibition space

[edit]

Frere Hall houses a number of stone busts, including that of King Edward VII, which was a gift from local Parsi philanthropist Seth Edulji Dinshaw.[5] Frere Hall also houses oil paintings by Sir Charles Pritchard, who was a former Commissioner of Sindh.

As of 2022, Frere Hall was open to the public, and it is also one of the most important tourist attractions in Karachi because of the building's notable architecture and its association with British rule in the Subcontinent.[3]

Gallery

[edit]-

Frere Hall is surrounded by gardens

-

Architectural details of Frere Hall

-

Frere Hall features Venetian-Gothic architectural elements

-

The hall's balconies feature Venetian-Gothic motifs

-

Staircases at the building are made of stone

-

Frere Hall at sunset.

-

Frere Hall Karachi.View from west side of Garden

-

Frere Hall, Karachi, 1860s

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Sir Bartle Frere (1870). The Speeches and Addresses of Sir H.B.E. Frere, G.C.S.I., K.C.B., D.C.L. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Frere Hall Bagh-e-Jinnah Karachi". White n Green.com website. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zulfishan Ghani (2 April 2015). "Heritage.....A marvellous piece of architecture". You! (Women's Magazine - Jang Group of Newspapers) website. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "KARACHI: Frere Hall library in a state of disrepair". Dawn (newspaper). 19 November 2003. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b J.W. Smyth, Gazetteer of the Province of Sind B Vol 1 Karachi District, Government Central Press, Bombay 1919. Reprinted by Pakistan Herald Publications (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Pg 70

- ^ Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Sátára. Government Central Press. 1885. p. 501. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

frere hall.

- ^ Downey, Jake (2003). Better Badminton for All. Pelham Books. p. 13. ISBN 0720702283.

- ^ a b c Shaikh, Sadeem (29 October 2015). "Frere Hall, a Hundred and Fifty Years Later - Architecture of Frere Hall Karachi". Youlin Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Sadequain's mural at Frere Hall lies ignored". The Express Tribune. 1 July 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "'Illegal' permission for yet another commercial activity at Frere Hall". The Express Tribune. 14 March 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2022.