Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

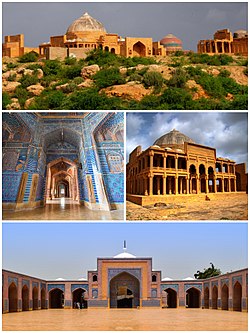

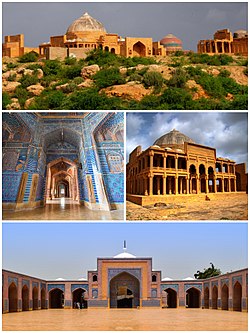

Thatta

View on Wikipedia

Thatta[a] is a city in the Pakistani province of Sindh. Thatta was the medieval capital of Sindh, and served as the seat of power for three successive dynasties. Its construction was ordered by Jam Nizamuddin II in 1495. Thatta's historic significance has yielded several monuments in and around the city. Thatta's Makli Necropolis, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is site of one of the world's largest cemeteries and has numerous monumental tombs built between the 14th and 18th centuries designed in a syncretic funerary style characteristic of lower Sindh. The city's 17th century Shah Jahan Mosque is richly embellished with decorative tiles, and is considered to have the most elaborate display of tile work in the South Asia.[1][2][3]

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]Thatta refers to riverside settlements. Villagers in the rural areas of lower Sindh often refer to the city as Thatta Nagar, or simply Nagar.[4] The name of Thatta, one of the oldest towns, was derived from the Persian term Tah-Tah which literally means "layer over layer", signifying a settlement that has gone through various civilizations.[5] Ḳāni, an 18th century scholar, gave two theories regarding the etymology of Thatta. The first theory suggests that Thatta is a distortion of ‘Teh Teh’ which refers to the migration of people from northern cities to Thatta. The second theory suggests that the name originates from thatt, the Sindhi term for a place of gathering.[3]

History

[edit]Early

[edit]Thatta may be the site of ancient Patala, the main port on the Indus in the time of Alexander the Great,[6] though the site of Patala has been subject to much debate.[7] Before it, Hindus called it Sarnee Nagar, but in 332 BC, Greeks first time called it Pattala or Patala then it became Nagar Tatta in Mughal Period. Muhammad bin Qasim captured the region in 711 CE after the defeating the Raja Dahir in a battle north of Thatta. Thatta is reported by some historians to have been the ancient seaport of Debal that was mentioned by the Arab conquerors, though others place the seaport at the site of modern Karachi.[8] At the time of the Umayyad conquests, small semi-nomadic tribes were living in the Sindh region. The Umayyad conquest introduced the religion of Islam into the hitherto mostly Hindu and Buddhist region.

Medieval

[edit]

Following Mahmud of Ghazna's invasion of Sindh in the early 11th century, the Ghaznavids installed Abdul Razzaq as Governor of Thatta in 1026.[9] Under the rule of the Ghaznavids the local chieftain Ibn Sumar, then ruler of Multan, seized power in Sindh and founded the Sumra dynasty, which ruled from Thatta from 1051 for the next 300 years. Under Sumra rule, Thatta's Ismaili Shia population was granted special protection.[10] The Sumra dynasty began to decline in power by the 13th century, though Thatta and the Indus Delta remained their last bastions of power until the mid 14th century.

In 1351, the Samma Dynasty, of Rajput descent from Sehwan, seized the city and made it their capital as well. It was during this time that the Makli Necropolis rose to prominence as a funerary site. Muhammad bin Tughluq died in 1351 during a campaign to capture Thatta.[11] Firuz Shah Tughlaq unsuccessfully attempted to subjugate Thatta twice; once in 1361 and again in 1365.[9]

Portuguese

[edit]In 1520, the Samma ruler Jam Feroz was defeated by Shah Beg of the Arghun-Tarkhun dynasty, which in turn had been displaced from Afghanistan by the expanding Timurid Empire in Central Asia. The Tarkhuns fell into disarray in the mid-1500s, prompting Muhammad Isa Tarkhun (Mirza Isa Khan I) to seek aid from the Portuguese in 1555. 700 Portuguese soldiers arrived in 28 ships to determine, at the time of their arrival, that Isa Tarkhun had already emerged victorious from the conflict. After the Tarkhuns refused to pay the Portuguese soldiers, the Portuguese plundered the town, robbing its enormous gold treasury, and killing many inhabitants.[12] Despite the 1557 Sack of Thatta, the 16th century Portuguese historian Diogo do Couto described Thatta as one of the richest cities of the Orient.[13]

Nevertheless, some Portuguese presence was early in the 16th century with the conquest of Hormuz by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1507, which started the relationship with Sindi.[14] Later in the first decade of the 16th century, traders created a factory (feitoria), and at the end of the 16th century a religious Order (Carmelitas Descalços) Secular Order of Discalced Carmelites a convent.

Mughal

[edit]

The city was destroyed by Mirza Jani Beg in the 16th century.[8] Beginning in 1592 during the reign of Emperor Akbar, Thatta was governed by the Mughal Empire based in Agra, which lead to a decline in the city's prosperity as some trade was shifted towards other Mughal ports.[13]

Shah Jahan, while still a prince, sought refuge in the city from his father Emperor Jahangir. In his reign, Thatta Subah was carved out of Subah of Multan, with provincial capital in Thatta. It consisted of modern Sindh. In 1626, Shah Jahan's 13th son, Lutfallah, was born in Thatta.[15] The city was almost destroyed by a devastating storm in 1637.[16] As a token of gratitude for the hospitality he had received in the city while still a prince, Shah Jahan bestowed the Shah Jahan Mosque to the city in 1647 as part of the city's rebuilding efforts, although it was not completed until 1659 under the reign of his son Aurangzeb.[16] Emperor Aurangzeb himself had also lived in Thatta for some time as governor of the lower Sindh.

Thatta regained some of its prosperity with the arrival of European merchants.[13] Between 1652 and 1660, the Dutch East India Company had a small trading post (comptoir or factory) in Thatta.[17] This competed with the English one, which was established in 1635 and closed in 1662. Thatta in the 1650s was noted to have 2,000 looms that produced cloth that was exported abroad to Asia and Portugal.[18] Thatta was also home to a thriving silk weaving industry, as well as leather products that were exported throughout South Asia.[18] The city was considered by visiting Augustinian friars in the 1650s to be a wealthy city, though the presence of transgender hijras were taken as a sign of the city's supposed moral depravity.[18]

Thatta'a revival was short lived as the Indus River silted in the second half of the 1600s, shifting its course further east and leading to the abandonment of the city as a seaport.[13] Despite the abandonment of the city's port functions, its Hindu merchants continued to play an important role in trade, and began using their own ships rather than relying on European ships for trade.[13] Traders were particularly active in the region around Masqat, in modern Oman, and members of Thatta's Bhatia caste established Masqat's first Hindu temple during this period.[13] Sindh remained an important economic centre during this period as well, and Thatta remained Sindh's largest economic centre, and its largest centre for textile production.[13]

Kalhora

[edit]The Kalhora dynasty of Jats began to gain influence as a dynasty of feudal lords in upper Sindh, where they ruled since the middle 16th century. They eventually brought Thatta under their control in 1736, and divided the Sind into two partitions, Upper Sind (capital Shikarpur) and Lower Sind, after which they moved the Lower Sind capital to Thatta from Siwistan, before eventually moving it to Hyderabad in 1789. A British factory was established there in 1758, but only lasted a few years.[19] Thatta continued to decline in the mid 18th century in importance as a trading centre throughout the 18th century, as much of the city's trading classes shifted to Nerunkot in northern Sindh, or to Gujarat.[20]

Talpur

[edit]In 1739, however, following the Battle of Karnal, the Mughal province of Sindh was fully ceded to Nadir Shah of the Persian Empire, after which Thatta fell into neglect, as the Indus river also began to silt. The city then came under the rule of the Talpur dynasty, who divided the Sind into three units Khairpur, Haiderabad, Mirpurkhas and seized Thatta from the Kalhoras. A second British comptoir was established during the Kalhora period in 1758, which operated until 1775.[21] In the early 19th century Thatta had declined to a population of about 20,000, from a high of 200,000 a century before.[22]

British

[edit]Talpur rule ended in 1843 on the battlefield of Miani when General Charles James Napier captured the Sindh for the British Empire, and moved the capital of the Sindh from Hyderabad to Karachi. In 1847, Thatta was administered as part of the Bombay Presidency. In 1920, the estimated population of the city was 10,800.[11]

Modern

[edit]

After the independence of Pakistan most of the city's Hindu population, though like much of Sindh, migrated to India, Thatta did not experience the widespread rioting that occurred in Punjab and Bengal.[23] In all, less than 500 Hindu were killed in all of Sindh between 1947 and 1948 as Sindhi Muslims largely resisted calls to turn against their Hindu neighbours.[24] Hindus did not flee Thatta en masse until riots erupted in Karachi on 6 January 1948, which sowed fear in Sindh's Hindus.[23]

In the 1970s under the rule of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Thatta's monuments were restored and some industry was relocated to Thatta.[22]

Geography

[edit]Thatta's geology is characterized by volcanic and sedimentary rocks that are similar to those in the Indus plain, and Thar Desert. Soil types in the region are silty, with some clay as well. Much of the soil is exposed to salinization from the Arabian Sea.[25]

Vegetation in Thatta is characterized by mangrove forests in the coastal region, with tropical-thorny shrubs elsewhere.[25]

Thatta is believed to be the birthplace of Ishta dev of Sindhi Hindus Jhulelal.

- Sri Chand Darbar

- Hanuman Mandir at Cinema road

- Jhule Lal Mandir Behrani at Goth

- Jhule Lal Mandir at Main Shahi Bazar

- Jhule Lal Mandir in a house at Sonara Bazar

- Mata Singh Bhawani Mandir at Makli

- Nath Marhi Mandir

- Seetla Mata Mandir in a house at Sonara Bazar

- Shiv Mandir at Maheshwari Mohala

Climate

[edit]Thatta has a hot semi-arid climate. The average annual rainfall is 250 mm (9.8 in), The average annual temperature in Thatta is 26.8 °C (80.2 °F).[26]

Last 10 years monsoon rains in Thatta were recorded as:

- 2009: 300+mm

- 2010: 300+mm

- 2011: 245mm

- 2012: 206mm

- 2013: 140mm

- 2014: 27mm

- 2015: 199.6mm

- 2016: 132mm

- 2017: 227mm

- 2018: 15mm

Sports

[edit]An association football club, Jeay Laal, was established in 2020.

Notable people

[edit]- Hashim Thattvi (1692–1761), Islamic scholar, the first to translate the Quran into Sindhi

- Mir Ahmed Nasrallah Thattvi (–1588), Islamic scholar at the court of Mughal emperor Akbar

- Mir Ali Sher Qaune Thattvi (1728–1788), Islamic historian and writer

- Tahir Muhammad Thattvi, poet and historian

See also

[edit]- Thatta District

- Sindh

- Indus Valley civilization

- History of Pakistan

- Zulfiqarabad

- List of cities founded by Alexander the Great

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Shah Jahan Mosque, Thatta". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Khazeni, Arash (2014). Sky Blue Stone: The Turquoise Trade in World History. Univ of California Press. ISBN 9780520279070. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ a b Rajani, Shayan (July 2020). "Competing for Distinction: Lineage and Individual Recognition in Eighteenth-Century Sindh". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 30 (3): 397–416. doi:10.1017/S1356186320000061. ISSN 1356-1863.

- ^ Dani, A (1982). Thatta: Islamic Architecture. Inst. of Islamic History, Culture and Civilization. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Siddiqi, Akhtar Husain; Bastian, Robert W. (1985). "Urban Place Names in Pakistan: A Reflection of Cultural Characteristics". Names. 29 (1): 71. OCLC 500207327.

- ^ James Rennell, Memoir of a map of Hindoostan:or the Mogul's Empire, London, 1783, p.57; William Vincent, The Voyage of Nearchus from the Indus to the Euphrates, London, 1797, p.146; William Robertson, An Historical Disquisition concerning the Knowledge which the Ancients had of India, A. Strahan, T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies; and E. Balfour, Edinburgh, 1799, p.47; Alexander Burnes, Travels into Bokhara: containing the narrative of a voyage on the Indus [...] and an account of a journey from India to Cabool, Tartary, and Persia, London, John Murray, 1835, Volume 1, p.27; Carl Ritter, Die Erdkunde im Verhältniss zur Natur und zur Geschichte des Menschen, Berlin, Reimer, 1835, Band IV, Fünfter Theil, pp.475–476.

- ^ A.H. Dani and P. Bernard, "Alexander and His Successors in Central Asia", in János Harmatta, B.N. Puri and G.F. Etemadi (editors), History of civilizations of Central Asia, Paris, UNESCO, Vol.II, 1994, p.85.

- ^ a b Ali, Mubarak 1994. McMurdo's & Delhoste's account of Sindh, Takhleeqat, Lahore, pp. 28-29.

- ^ a b Rickmers, Christian Mabel Duff (1899). The Chronology of India, from the Earliest Times to the Beginning Os the Sixteenth Century. A. Constable & Company. p. 224. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

thatta.

- ^ Daftary, Farhad (2005). Ismailis in Medieval Muslim Societies. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857713872. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b Murray, John (1920). Handbook to India, Burma, and Ceylon. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816061846.

- ^ a b c d e f g Markovits, Claude (2000). The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750–1947: Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139431279. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Sprengard, Karl Anton; Ptak, Roderich (1994). Maritime Asia: Profit Maximisation, Ethics and Trade Structure C. 1300-1800 editado por Karl Anton Sprengard, Roderich Ptak. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447035217. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Nicoll, Fergus (2009). Shah Jahan. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0670083039. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b Asher, Catherine (1992). Architecture of Mughal India, Part 1, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521267281. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ Floor, Willem, 1993-4. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Diewel-Sind (Pakistan) in the 17th and 18th centuries. Institute of Central & West Asian Studies, University of Karachi.

- ^ a b c Lach, Donald (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 2, South Asia. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226466972. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 451.

- ^ Oonk, Gijsbert (2007). Global Indian Diasporas: Exploring Trajectories of Migration and Theory. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9053560358. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Ali, Mubarak, 2005. The English Factory in Sindh, Zahoor Ahmed Khan Fiction House, Lahore

- ^ a b Burki, Shahid Javed (2015). Historical Dictionary of Pakistan. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442241480. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b Kumar, Priya (2 December 2016). "Sindh, 1947 and Beyond". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 39 (4): 773–789. doi:10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752.

- ^ Chitkara, M. G. (1996). Mohajir's Pakistan. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-8170247463. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ a b Sindhu, Abdul Shakoor (2010). "District Thatta – Hazard, Vulnerability and Development Profile" (PDF). Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI), Islamabad. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Pakistan flood victims flee Thatta Archived 30 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

External links

[edit] Thatta travel guide from Wikivoyage

Thatta travel guide from Wikivoyage