Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

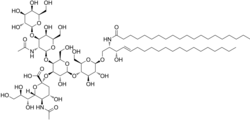

| IUPAC name

(2S,4S,5R,6R)-5-acetamido-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-5-[(2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-3-acetamido-5-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-4-[(2R,3R,4S,5R,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxyoxan-2-yl]oxy-2-[(2R,3S,4R,5R,6R)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-[(E,2R,3S)-3-hydroxy-2-(icosanoylamino)icos-4-enoxy]-2-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-3-yl]oxy-3-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-4-yl]oxy-4-hydroxy-6-[(1R,2R)-1,2,3-trihydroxypropyl]oxane-2-carboxylic acid

| |

| Other names

Monosialotetrahexosylganglioside

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| MeSH | G(M1)+Ganglioside |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C77H139N3O31 | |

| Molar mass | 1602.949 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

GM1 (monosialotetrahexosylganglioside) the "prototype" ganglioside, is a member of the ganglio series of gangliosides which contain one sialic acid residue. GM1 has important physiological properties and impacts neuronal plasticity and repair mechanisms, and the release of neurotrophins in the brain. Besides its function in the physiology of the brain, GM1 acts as the site of binding for both cholera toxin and E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin (Traveller's diarrhea).[1][2]

GM1 and inherited disease

[edit]Galactosidases are enzymes that break down GM1, and the failure to remove GM1 results in GM1 gangliosidosis.[3] GM1 gangliosidosis are inherited disorders that progressively destroy neurons in the brain and spinal cord as GM1 accumulates. Without treatment, this results in developmental decline and muscle weakness, eventually leading to severe retardation and death.

GM1 and acquired disease

[edit]Antibodies to GM1 are increased in Guillain–Barré syndrome, dementia and lupus but their function is not clear.[4] There is some evidence to suggest antibodies against GM1 are associated with diarrhea in Guillain–Barré syndrome.[5]

GM1 antibodies are also seen in multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN), a rare antibody-mediated inflammatory neuropathy.

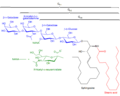

GM1 and the cholera toxin

[edit]The bacteria Vibrio cholerae produces a multimeric toxin called the cholera toxin. The secreted toxin attaches to the surface of the host mucosa cell by binding to GM1 gangliosides. GM1 consists of a sialic acid-containing oligosaccharide covalently attached to a ceramide lipid. The A1 subunit of this toxin will gain entry to intestinal epithelial cells with the assistance of the B subunit via the GM1 ganglioside receptor. Once inside, the A1 subunit will ADP ribosylate the Gs alpha subunit, which will prevent its GTPase activity. This will lock it in the active state and it will continuously stimulate adenylate cyclase. The sustained adenylate cyclase activity will lead to a sustained increase of cAMP which will cause electrolyte and water loss, causing diarrhea.[citation needed]

The SGLT1 receptor is present in the small intestine. When the cholera patient is given a solution containing water, sodium and glucose, the SGLT1 receptor will reabsorb sodium and glucose, while water will be passively absorbed with the sodium. This will replace the water and electrolyte loss in the cholera-induced diarrhea.

Therapeutic applications

[edit]Because of GM1's close role in neuron repair mechanisms, it has been investigated as a possible drug to slow or even reverse the progression of a wide range of neurodegenerative conditions. Controlled phase II studies have indicated that GM1 can ease the symptoms of Parkinson's disease, presumably by countering degeneration of the substantia nigra,[6] and a similar methodology has been pursued to try and limit cellular damage from necrosis and apoptosis occurring after acute spinal cord injury.[7]

Additional images

[edit]-

Sphingolipidoses

-

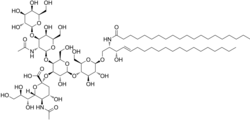

Structures of GM1, GM2, GM3 gangliosides

References

[edit]- ^ Mocchetti I (2005). "Exogenous gangliosides, neuronal plasticity and repair, and the neurotrophins". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 (19–20): 2283–94. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5188-y. PMC 11139125. PMID 16158191.

- ^ Chen JC, Chang YS, Wu SL, et al. (September 2007). "Inhibition of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin-induced diarrhea by Chaenomeles speciosa". J Ethnopharmacol. 113 (2): 233–9. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.031. PMID 17624704.

- ^ U.S. National Library of Medicine. "GM1 gangliosidosis". Genetic Home Reference. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Bansal AS, Abdul-Karim B, Malik RA, et al. (1994). "IgM ganglioside GM1 antibodies in patients with autoimmune disease or neuropathy, and controls". J. Clin. Pathol. 47 (4): 300–2. doi:10.1136/jcp.47.4.300. PMC 501930. PMID 8027366.

- ^ Irie S, Saito T, Kanazawa N, et al. (1997). "Relationships between anti-ganglioside antibodies and clinical characteristics of Guillain–Barré syndrome". Intern. Med. 36 (9): 607–12. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.36.607. PMID 9313102.

- ^ Thomas Jefferson University (December 2012). "GM1 Ganglioside Effects on Parkinson's Disease". Clinical Trials.gov.

- ^ McDonald, John (September 1999). "Repairing the Damaged Spinal Cord". Scientific American: 69.