Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sphingomyelin

View on Wikipedia

Sphingomyelin (SPH, /ˌsfɪŋɡoʊˈmaɪəlɪn/) is a type of sphingolipid found in animal cell membranes, especially in the membranous myelin sheath that surrounds some nerve cell axons. It usually consists of phosphocholine and ceramide, or a phosphoethanolamine head group; therefore, sphingomyelins can also be classified as sphingophospholipids.[1][2] In humans, SPH represents ~85% of all sphingolipids, and typically makes up 10–20 mol % of plasma membrane lipids.

Sphingomyelin was first isolated by German chemist Johann L.W. Thudicum in the 1880s.[3] The structure of sphingomyelin was first reported in 1927 as N-acyl-sphingosine-1-phosphorylcholine.[3] Sphingomyelin content in mammals ranges from 2 to 15% in most tissues, with higher concentrations found in nerve tissues, red blood cells, and the ocular lenses. Sphingomyelin has significant structural and functional roles in the cell. It is a plasma membrane component and participates in many signaling pathways. The metabolism of sphingomyelin creates many products that play significant roles in the cell.[3]

Physical characteristics

[edit]

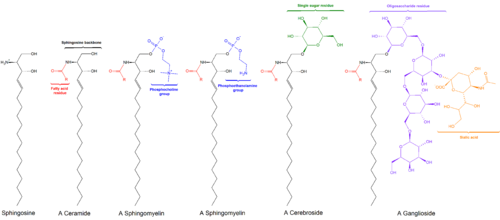

Black: Sphingosine

Red: Phosphocholine

Blue: Fatty acid

Composition

[edit]Sphingomyelin consists of a phosphocholine head group, a sphingosine, and a fatty acid. It is one of the few membrane phospholipids not synthesized from glycerol. The sphingosine and fatty acid can collectively be categorized as a ceramide. This composition allows sphingomyelin to play significant roles in signaling pathways: the degradation and synthesis of sphingomyelin produce important second messengers for signal transduction.

Sphingomyelin obtained from natural sources, such as eggs or bovine brain, contains fatty acids of various chain length. Sphingomyelin with set chain length, such as palmitoylsphingomyelin with a saturated 16 acyl chain, is available commercially.[4]

Properties

[edit]Ideally, sphingomyelin molecules are shaped like a cylinder, however many molecules of sphingomyelin have a significant chain mismatch (the lengths of the two hydrophobic chains are significantly different).[5] The hydrophobic chains of sphingomyelin tend to be much more saturated than other phospholipids. The main transition phase temperature of sphingomyelins is also higher compared to the phase transition temperature of similar phospholipids, near 37 °C. This can introduce lateral heterogeneity in the membrane, generating domains in the membrane bilayer.[5]

Sphingomyelin undergoes significant interactions with cholesterol. Cholesterol has the ability to eliminate the liquid to solid phase transition in phospholipids. Due to sphingomyelin transition temperature being within physiological temperature ranges, cholesterol can play a significant role in the phase of sphingomyelin. Sphingomyelin are also more prone to intermolecular hydrogen bonding than other phospholipids.[6]

Location

[edit]Sphingomyelin is synthesized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it can be found in low amounts, and at the trans Golgi. It is enriched at the plasma membrane with a greater concentration on the outer than the inner leaflet.[7] The Golgi complex represents an intermediate between the ER and plasma membrane, with slightly higher concentrations towards the trans side.[8]

Metabolism

[edit]Synthesis

[edit]The synthesis of sphingomyelin involves the enzymatic transfer of a phosphocholine from phosphatidylcholine to a ceramide. The first committed step of sphingomyelin synthesis involves the condensation of L-serine and palmitoyl-CoA. This reaction is catalyzed by serine palmitoyltransferase. The product of this reaction is reduced, yielding dihydrosphingosine. The dihydrosphingosine undergoes N-acylation followed by desaturation to yield a ceramide. Each one of these reactions occurs at the cytosolic surface of the endoplasmic reticulum. The ceramide is transported to the Golgi apparatus where it can be converted to sphingomyelin. Sphingomyelin synthase is responsible for the production of sphingomyelin from ceramide. Diacylglycerol is produced as a byproduct when the phosphocholine is transferred.[9]

Degradation

[edit]Sphingomyelin breakdown is responsible for initiating many universal signaling pathways. It is hydrolyzed by sphingomyelinases (sphingomyelin specific type-C phospholipases).[7] The phosphocholine head group is released into the aqueous environment while the ceramide diffuses through the membrane.

Function

[edit]Membranes

[edit]The membranous myelin sheath that surrounds and electrically insulates many nerve cell axons is particularly rich in sphingomyelin, suggesting its role as an insulator of nerve fibers.[2] The plasma membrane of other cells is also abundant in sphingomyelin, though it is largely to be found in the exoplasmic leaflet of the cell membrane. There is, however, some evidence that there may also be a sphingomyelin pool in the inner leaflet of the membrane.[10][11] Moreover, neutral sphingomyelinase-2 – an enzyme that breaks down sphingomyelin into ceramide – has been found to localise exclusively to the inner leaflet, further suggesting that there may be sphingomyelin present there.[12]

Signal transduction

[edit]The function of sphingomyelin remained unclear until it was found to have a role in signal transduction.[13] It has been discovered that sphingomyelin plays a significant role in cell signaling pathways. The synthesis of sphingomyelin at the plasma membrane by sphingomyelin synthase 2 produces diacylglycerol, which is a lipid-soluble second messenger that can pass along a signal cascade. In addition, the degradation of sphingomyelin can produce ceramide which is involved in the apoptotic signaling pathway.

Apoptosis

[edit]Sphingomyelin has been found to have a role in cell apoptosis by hydrolyzing into ceramide. Studies in the late 1990s had found that ceramide was produced in a variety of conditions leading to apoptosis.[14] It was then hypothesized that sphingomyelin hydrolysis and ceramide signaling were essential in the decision of whether a cell dies. In the early 2000s new studies emerged that defined a new role for sphingomyelin hydrolysis in apoptosis, determining not only when a cell dies but how.[14] After more experimentation it has been shown that if sphingomyelin hydrolysis happens at a sufficiently early point in the pathway the production of ceramide may influence either the rate and form of cell death or work to release blocks on downstream events.[14]

Lipid rafts

[edit]Sphingomyelin, as well as other sphingolipids, are associated with lipid microdomains in the plasma membrane known as lipid rafts. Lipid rafts are characterized by the lipid molecules being in the lipid ordered phase, offering more structure and rigidity compared to the rest of the plasma membrane. In the rafts, the acyl chains have low chain motion but the molecules have high lateral mobility. This order is in part due to the higher transition temperature of sphingolipids as well as the interactions of these lipids with cholesterol. Cholesterol is a relatively small, nonpolar molecule that can fill the space between the sphingolipids that is a result of the large acyl chains. Lipid rafts are thought to be involved in many cell processes, such as membrane sorting and trafficking, signal transduction, and cell polarization.[15] Excessive sphingomyelin in lipid rafts may lead to insulin resistance.[16]

Due to the specific types of lipids in these microdomains, lipid rafts can accumulate certain types of proteins associated with them, thereby increasing the special functions they possess. Lipid rafts have been speculated to be involved in the cascade of cell apoptosis.[17]

Abnormalities and associated diseases

[edit]Sphingomyelin can accumulate in a rare hereditary disease called Niemann–Pick disease, types A and B. It is a genetically-inherited disease caused by a deficiency in the lysosomal enzyme acid sphingomyelinase, which causes the accumulation of sphingomyelin in spleen, liver, lungs, bone marrow, and brain, causing irreversible neurological damage. Of the two types involving sphingomyelinase, type A occurs in infants. It is characterized by jaundice, an enlarged liver, and profound brain damage. Children with this type rarely live beyond 18 months. Type B involves an enlarged liver and spleen, which usually occurs in the pre-teen years. The brain is not affected. Most patients present with <1% normal levels of the enzyme in comparison to normal levels. A hemolytic protein, lysenin, may be a valuable probe for sphingomyelin detection in cells of Niemann-Pick A patients.[1]

As a result of the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis (MS), the myelin sheath of neuronal cells in the brain and spinal cord is degraded, resulting in loss of signal transduction capability. MS patients exhibit upregulation of certain cytokines in the cerebrospinal fluid, particularly tumor necrosis factor alpha. This activates sphingomyelinase, an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin to ceramide; sphingomyelinase activity has been observed in conjunction with cellular apoptosis.[18]

An excess of sphingomyelin in the red blood cell membrane (as in abetalipoproteinemia) causes excess lipid accumulation in the outer leaflet of the red blood cell plasma membrane. This results in abnormally shaped red cells called acanthocytes.

Additional images

[edit]-

Ball-and-stick model of sphingomyelin

-

Skeletal formula of sphingomyelin

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bruhn, Heike; Winkelmann, Julia; Andersen, Christian; Andrä, Jörg; Leippe, Matthias (2006-01-01). "Dissection of the mechanisms of cytolytic and antibacterial activity of lysenin, a defence protein of the annelid Eisenia fetida". Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 30 (7): 597–606. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2005.09.002. ISSN 0145-305X. PMID 16386304.

- ^ a b Donald J. Voet; Judith G. Voet; Charlotte W. Pratt (2008). "Lipids, Bilayers and Membranes". Principles of Biochemistry, Third edition. Wiley. p. 252. ISBN 978-0470-23396-2.

- ^ a b c Ramstedt, B; Slotte, JP (30 October 2002). "Membrane properties of sphingomyelins". FEBS Letters. 531 (1): 33–7. Bibcode:2002FEBSL.531...33R. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03406-3. PMID 12401199. S2CID 35378780.

- ^ "Avanti Polar Lipids". Archived from the original on 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- ^ a b Barenholz, Y; Thompson, TE (November 1999). "Sphingomyelin: biophysical aspects". Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 102 (1–2): 29–34. doi:10.1016/S0009-3084(99)00072-9. PMID 11001558.

- ^ Massey, John B. (9 February 2001). "Interaction of ceramides with phosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin and sphingomyelin/cholesterol bilayers". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1510 (1–2): 167–84. doi:10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00344-8. PMID 11342156.

- ^ a b Testi, Roberto (December 1996). "Sphingomyelin breakdown and cell fate". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 21 (12): 468–71. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(96)10056-6. PMID 9009829.

- ^ Brügger, B; Sandhoff, R; Wegehingel, S; Gorgas, K; Malsam, J; Helms, JB; Lehmann, WD; Nickel, W; Wieland, FT (30 October 2000). "Evidence for segregation of sphingomyelin and cholesterol during formation of COPI-coated vesicles". The Journal of Cell Biology. 151 (3): 507–18. doi:10.1083/jcb.151.3.507. PMC 2185577. PMID 11062253.

- ^ Tafesse, FG; Ternes, P; Holthuis, JC (6 October 2006). "The multigenic sphingomyelin synthase family". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (40): 29421–5. doi:10.1074/jbc.R600021200. hdl:1874/19992. PMID 16905542.

- ^ Linardic CM, Hannun YA (1994). "Identification of a distinct pool of sphingomyelin involved in the sphingomyelin cycle". J. Biol. Chem. 269 (38): 23530–7. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)31548-X. PMID 8089120.

- ^ Zhang, P.; Liu, B.; Jenkins, G. M.; Hannun, Y. A.; Obeid, L. M. (1997). "Expression of Neutral Sphingomyelinase Identifies a Distinct Pool of Sphingomyelin Involved in Apoptosis". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (15): 9609–9612. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.15.9609. PMID 9092485.

- ^ Tani, M.; Hannun, Y. A. (2007). "Analysis of membrane topology of neutral sphingomyelinase 2". FEBS Letters. 581 (7): 1323–1328. Bibcode:2007FEBSL.581.1323T. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.046. PMC 1868537. PMID 17349629.

- ^ Kolesnick (1994). "Signal transduction through the sphingomyelin pathway". Mol Chem Neuropathol. 21 (2–3): 287–97. doi:10.1007/BF02815356. PMID 8086039. S2CID 30521415.

- ^ a b c Green, Douglas R. (10 July 2000). "Apoptosis and sphingomyelin hydrolysis. The flip side". The Journal of Cell Biology. 150 (1): F5–7. doi:10.1083/jcb.150.1.F5. PMC 2185551. PMID 10893276.

- ^ Giocondi, MC; Boichot, S; Plénat, T; Le Grimellec, CC (August 2004). "Structural diversity of sphingomyelin microdomains". Ultramicroscopy. 100 (3–4): 135–43. doi:10.1016/j.ultramic.2003.11.002. PMID 15231303.

- ^ Li, Z; Zhang, H; Liu, J; Liang, CP; Li, Y; Li, Y; Teitelman, G; Beyer, T; Bui, HH; Peake, DA; Zhang, Y; Sanders, PE; Kuo, MS; Park, TS; Cao, G; Jiang, XC (October 2011). "Reducing plasma membrane sphingomyelin increases insulin sensitivity". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 31 (20): 4205–18. doi:10.1128/MCB.05893-11. PMC 3187286. PMID 21844222.

- ^ Zhang, L; Hellgren, LI; Xu, X (3 May 2006). "Enzymatic production of ceramide from sphingomyelin". Journal of Biotechnology. 123 (1): 93–105. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.10.020. PMID 16337303.

- ^ Jana, A; Pahan, K (December 2010). "Sphingolipids in multiple sclerosis". Neuromolecular Medicine. 12 (4): 351–61. doi:10.1007/s12017-010-8128-4. PMC 2987401. PMID 20607622.

External links

[edit]- Sphingomyelins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)