Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Microglia

View on Wikipedia| Microglia | |

|---|---|

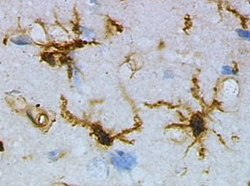

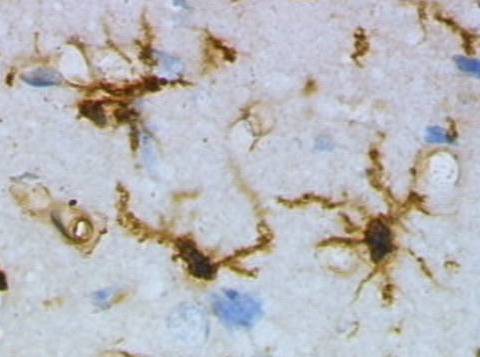

Microglia in resting state from rat cortex before traumatic brain injury (lectin staining with HRP) | |

Microglia/macrophage – activated form from rat cortex after traumatic brain injury (lectin staining with HRP) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Primitive yolk-sac derived macrophage |

| System | Central nervous system |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D017628 |

| TH | H2.00.06.2.00004, H2.00.06.2.01025 |

| FMA | 54539 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Microglia are a type of glial cell located throughout the brain and spinal cord of the central nervous system (CNS).[1] Microglia account for about around 5–10% of cells found within the brain.[2][3] As the resident macrophage cells, they act as the first and main form of active immune defense in the CNS.[4] Microglia originate in the yolk sac under tightly regulated molecular conditions.[5] These cells (and other neuroglia including astrocytes) are distributed in large non-overlapping regions throughout the CNS.[6][7] Microglia are key cells in overall brain maintenance – they are constantly scavenging the CNS for plaques, damaged or unnecessary neurons and synapses, and infectious agents.[8] Since these processes must be efficient to prevent potentially fatal damage, microglia are extremely sensitive to even small pathological changes in the CNS.[9] This sensitivity is achieved in part by the presence of unique potassium channels that respond to even small changes in extracellular potassium.[8] Recent evidence shows that microglia are also key players in the sustainment of normal brain functions under healthy conditions.[10] Microglia also constantly monitor neuronal functions through direct somatic contacts via their microglial processes, and exert neuroprotective effects when needed.[11][12]

The brain and spinal cord, which make up the CNS, are not usually accessed directly by pathogenic factors in the body's circulation due to a series of endothelial cells known as the blood–brain barrier, or BBB. The BBB prevents most infections from reaching the vulnerable nervous tissue. In the case where infectious agents are directly introduced to the brain or cross the blood–brain barrier, microglial cells must react quickly to decrease inflammation and destroy the infectious agents before they damage the sensitive neural tissue. Due to the lack of antibodies from the rest of the body (few antibodies are small enough to cross the blood–brain barrier), microglia must be able to recognize foreign bodies, swallow them, and act as antigen-presenting cells activating T-cells.

History

[edit]The ability to view and characterize different neural cells including microglia began in 1880 when Nissl staining was developed by Franz Nissl. Franz Nissl and William Ford Robertson first described microglial cells during their histology experiments. The cell staining techniques in the 1880s showed that microglia are related to macrophages. The activation of microglia and formation of ramified microglial clusters was first noted by Victor Babeş while studying a rabies case in 1897. Babeş noted the cells were found in a variety of viral brain infections but did not know what the clusters of microglia he saw were.[13] The Spanish scientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal defined a "third element" (cell type) besides neurons and astrocytes.[14] Pío del Río Hortega, a student of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, first called the cells "microglia" around 1920. He went on to characterize microglial response to brain lesions in 1927 and note the "fountains of microglia" present in the corpus callosum and other perinatal white matter areas in 1932. After many years of research Rio Hortega became generally considered as the "father of microglia".[15][16] For a long period of time little improvement was made in our knowledge of microglia. Then, in 1988, Hickey and Kimura showed that perivascular microglial cells are bone-marrow derived, and express high levels of MHC class II proteins used for antigen presentation. This confirmed Pio Del Rio-Hortega's postulate that microglial cells functioned similarly to macrophages by performing phagocytosis and antigen presentation.[citation needed]

At the end of the 20th century, the experimental psychology group at Oxford University classified microglial cells into 3 types according to their morphology, tissue location and duration of phagocytic activity.[17] Today, many researchers around the world are trying to establish a relationship between microglial cell morphology and the levels of expression of immune mediators by microglial cells, using different software.[18].

Forms

[edit]

Microglial cells are extremely plastic, and undergo a variety of structural changes based on location and system needs. This level of plasticity is required to fulfill the vast variety of functions that microglia perform. The ability to transform distinguishes microglia from macrophages, which must be replaced on a regular basis, and provides them the ability to defend the CNS on extremely short notice without causing immunological disturbance.[8] Microglia adopt a specific form, or phenotype, in response to the local conditions and chemical signals they have detected.[19] It has also been shown, that tissue-injury related ATP signalling plays a crucial role in the phenotypic transformation of microglia.[20]

Ramified

[edit]This form of microglial cell is commonly found at specific locations throughout the entire brain and spinal cord in the absence of foreign material or dying cells. This "resting" form of microglia is composed of long branching processes and a small cellular body. Unlike the amoeboid forms of microglia, the cell body of the ramified form remains in place while its branches are constantly moving and surveying the surrounding area. The branches are very sensitive to small changes in physiological condition and require very specific culture conditions to observe in vitro.[19]

Unlike activated or ameboid microglia, ramified microglia do not phagocytose cells and secrete fewer immunomolecules (including the MHC class I/II proteins). Microglia in this state are able to search for and identify immune threats while maintaining homeostasis in the CNS.[21][22][23] Although this is considered the resting state, microglia in this form are still extremely active in chemically surveying the environment. Ramified microglia can be transformed into the activated form at any time in response to injury or threat.[19]

Reactive (activated)

[edit]Although historically frequently used, the term "activated" microglia should be replaced by "reactive" microglia.[24] Indeed, apparently quiescent microglia are not devoid of active functions and the "activation" term is misleading as it tends to indicate an "all or nothing" polarization of cell reactivity. The marker Iba1, which is upregulated in reactive microglia, is often used to visualize these cells.[25]

Non-phagocytic

[edit]This state is actually part of a graded response as microglia move from their ramified form to their fully active phagocytic form. Microglia can be activated by a variety of factors including: pro-inflammatory cytokines, cell necrosis factors, lipopolysaccharide, and changes in extracellular potassium (indicative of ruptured cells). Once activated the cells undergo several key morphological changes including the thickening and retraction of branches, uptake of MHC class I/II proteins, expression of immunomolecules, secretion of cytotoxic factors, secretion of recruitment molecules, and secretion of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules (resulting in a pro-inflammation signal cascade). Activated non-phagocytic microglia generally appear as "bushy", "rods", or small ameboids depending on how far along the ramified to full phagocytic transformation continuum they are. In addition, the microglia also undergo rapid proliferation in order to increase their numbers. From a strictly morphological perspective, the variation in microglial form along the continuum is associated with changing morphological complexity and can be quantitated using the methods of fractal analysis, which have proven sensitive to even subtle, visually undetectable changes associated with different morphologies in different pathological states.[8][21][22][26]

Phagocytic

[edit]Activated phagocytic microglia are the maximally immune-responsive form of microglia. These cells generally take on a large, ameboid shape, although some variance has been observed. In addition to having the antigen presenting, cytotoxic and inflammation-mediating signaling of activated non-phagocytic microglia, they are also able to phagocytose foreign materials and display the resulting immunomolecules for T-cell activation. Phagocytic microglia travel to the site of the injury, engulf the offending material, and secrete pro-inflammatory factors to promote more cells to proliferate and do the same. Activated phagocytic microglia also interact with astrocytes and neural cells to fight off any infection or inflammation as quickly as possible with minimal damage to healthy brain cells.[8][21]

Amoeboid

[edit]This shape allows the microglia free movement throughout the neural tissue, which allows it to fulfill its role as a scavenger cell. Amoeboid microglia are able to phagocytose debris, but do not fulfill the same antigen-presenting and inflammatory roles as activated microglia. Amoeboid microglia are especially prevalent during the development and rewiring of the brain, when there are large amounts of extracellular debris and apoptotic cells to remove. This form of microglial cell is found mainly within the perinatal white matter areas in the corpus callosum known as the "Fountains of Microglia".[8][22][27]

Perivascular

[edit]Unlike the other types of microglia mentioned above, "perivascular" microglia refers to the location of the cell, rather than its form/function. Perivascular microglia are however often confused with perivascular macrophages (PVMs),[28] which are found encased within the walls of the basal lamina, so care must be taken to determine which of these two cell types authors of publications are referring to. PVMs, unlike normal microglia, are replaced by bone marrow-derived precursor cells on a regular basis, and express MHC class II antigens regardless of their environment.[8]

Juxtavascular

[edit]"Perivascular microglia" and "juxtavascular microglia" are different names for the same type of cell. Confusion has arisen due to the misuse of the term perivascular microglia to refer to perivascular macrophages,[28] which are a different type of cell. Juxtavascular microglia/perivascular microglia are found making direct contact with the basal lamina wall of blood vessels but are not found within the walls. In this position they can interact with both endothelial cells and pericytes.[29][30] Like perivascular cells, they express MHC class II proteins even at low levels of inflammatory cytokine activity. Unlike perivascular cells, but similar to other microglia, juxtavascular microglia do not exhibit rapid turnover or replacement with myeloid precursor cells on a regular basis.[8]

Functions

[edit]

Microglial cells fulfill a variety of different tasks within the CNS mainly related to both immune response and maintaining homeostasis. The following are some of the major known functions carried out by these cells.[citation needed]

Scavenging

[edit]In addition to being very sensitive to small changes in their environment, each microglial cell also physically surveys its domain on a regular basis. This action is carried out in the ameboid and resting states via highly motile microglial processes.[12] While moving through its set region, if the microglial cell finds any foreign material, damaged cells, apoptotic cells, neurofibrillary tangles, DNA fragments, or plaques it will activate and phagocytose the material or cell. In this manner microglial cells also act as "housekeepers", cleaning up random cellular debris.[21] During developmental wiring of the brain, microglial cells play a large role regulating numbers of neural precursor cells and removing apoptotic neurons. There is also evidence that microglia can refine synaptic circuitry by engulfing and eliminating synapses.[31] Post development, the majority of dead or apoptotic cells are found in the cerebral cortex and the subcortical white matter. This may explain why the majority of ameboid microglial cells are found within the "fountains of microglia" in the cerebral cortex.[27]

Phagocytosis

[edit]The main role of microglia, phagocytosis, involves the engulfing of various materials. Engulfed materials generally consist of cellular debris, lipids, and apoptotic cells in the non-inflamed state, and invading virus, bacteria, or other foreign materials in the inflamed state. Once the microglial cell is "full" it stops phagocytic activity and changes into a relatively non-reactive gitter cell.[32]

Extracellular signaling

[edit]A large part of microglial cell's role in the brain is maintaining homeostasis in non-infected regions and promoting inflammation in infected or damaged tissue. Microglia accomplish this through an extremely complicated series of extracellular signaling molecules which allow them to communicate with other microglia, astrocytes, neurons, T-cells, and myeloid progenitor cells. As mentioned above the cytokine IFN-γ can be used to activate microglial cells. In addition, after becoming activated with IFN-γ, microglia also release more IFN-γ into the extracellular space. This activates more microglia and starts a cytokine induced activation cascade rapidly activating all nearby microglia. Microglia-produced TNF-α causes neural tissue to undergo apoptosis and increases inflammation. IL-8 promotes B-cell growth and differentiation, allowing it to assist microglia in fighting infection. Another cytokine, IL-1, inhibits the cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β, which downregulate antigen presentation and pro-inflammatory signaling. Additional dendritic cells and T-cells are recruited to the site of injury through the microglial production of the chemotactic molecules like MDC, IL-8, and MIP-3β. Finally, PGE2 and other prostanoids prevent chronic inflammation by inhibiting microglial pro-inflammatory response and downregulating Th1 (T-helper cell) response.[21]

Antigen presentation

[edit]As mentioned above, resident non-activated microglia act as poor antigen presenting cells due to their lack of MHC class I/II proteins. Upon activation they rapidly express MHC class I/II proteins and quickly become efficient antigen presenters. In some cases, microglia can also be activated by IFN-γ to present antigens, but do not function as effectively as if they had undergone uptake of MHC class I/II proteins. During inflammation, T-cells cross the blood–brain barrier thanks to specialized surface markers and then directly bind to microglia in order to receive antigens. Once they have been presented with antigens, T-cells go on to fulfill a variety of roles including pro-inflammatory recruitment, formation of immunomemories, secretion of cytotoxic materials, and direct attacks on the plasma membranes of foreign cells.[8][21]

Cytotoxicity

[edit]In addition to being able to destroy infectious organisms through cell to cell contact via phagocytosis, microglia can also release a variety of cytotoxic substances.[33] Microglia in culture secrete large amounts of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide in a process known as 'respiratory burst'. Both of these chemicals can directly damage cells and lead to neuronal cell death. Proteases secreted by microglia catabolise specific proteins causing direct cellular damage, while cytokines like IL-1 promote demyelination of neuronal axons. Finally, microglia can injure neurons through NMDA receptor-mediated processes by secreting glutamate, aspartate and quinolinic acid. Cytotoxic secretion is aimed at destroying infected neurons, virus, and bacteria, but can also cause large amounts of collateral neural damage. As a result, chronic inflammatory response can result in large scale neural damage as the microglia ravage the brain in an attempt to destroy the invading infection.[8] Edaravone, a radical scavenger, precludes oxidative neurotoxicity precipitated by activated microglia.[34]

Synaptic stripping

[edit]In a phenomenon first noticed in spinal lesions by Blinzinger and Kreutzberg in 1968, post-inflammation microglia remove the branches from nerves near damaged tissue. This helps promote regrowth and remapping of damaged neural circuitry.[8] It has also been shown that microglia are involved in the process of synaptic pruning during brain development.[35]

Promotion of repair

[edit]Post-inflammation, microglia undergo several steps to promote regrowth of neural tissue. These include synaptic stripping, secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines, recruitment of neurons and astrocytes to the damaged area, and formation of gitter cells. Without microglial cells regrowth and remapping would be considerably slower in the resident areas of the CNS and almost impossible in many of the vascular systems surrounding the brain and eyes.[8][36] Recent research verified, that microglial processes constantly monitor neuronal functions through specialized somatic junctions, and sense the "well-being" of nerve cells. Via this intercellular communication pathway, microglia are capable of exerting robust neuroprotective effects, contributing significantly to repair after brain injury.[11] Microglia have also been shown to contribute to proper brain development, through contacting immature, developing neurons.[37]

Development

[edit]

For a long time it was thought that microglial cells differentiate in the bone marrow from hematopoietic stem cells, the progenitors of all blood cells. However, recent studies show that microglia originate in the yolk sac during a remarkably restricted embryonal period and populate the brain parenchyma guided by a precisely orchestrated molecular process.[5] Yolk sac progenitor cells require activation colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) for migration into the brain and differentiation into microglia.[38] Additionally, the greatest contribution to microglial repopulation is based upon its local self-renewal, both in steady state and disease, while circulating monocytes may also contribute to a lesser extent, especially in disease.[5][39]

Monocytes can also differentiate into myeloid dendritic cells and macrophages in the peripheral systems. Like macrophages in the rest of the body, microglia use phagocytic and cytotoxic mechanisms to destroy foreign materials. Microglia and macrophages both contribute to the immune response by acting as antigen presenting cells, as well as promoting inflammation and homeostatic mechanisms within the body by secreting cytokines and other signaling molecules.[40]

In their downregulated form, microglia lack the MHC class I/MHC class II proteins, IFN-γ cytokines, CD45 antigens, and many other surface receptors required to act in the antigen-presenting, phagocytic, and cytotoxic roles that distinguish normal macrophages. Microglia also differ from macrophages in that they are much more tightly regulated spatially and temporally in order to maintain a precise immune response.[21]

Another difference between microglia and other cells that differentiate from myeloid progenitor cells is the turnover rate. Macrophages and dendritic cells are constantly being used up and replaced by myeloid progenitor cells which differentiate into the needed type. Due to the blood–brain barrier, it would be fairly difficult for the body to constantly replace microglia. Therefore, instead of constantly being replaced with myeloid progenitor cells, the microglia maintain their status quo while in their quiescent state, and then, when they are activated, they rapidly proliferate in order to keep their numbers up. Bone chimera studies have shown, however, that in cases of extreme infection the blood–brain barrier will weaken, and microglia will be replaced with haematogenous, marrow-derived cells, namely myeloid progenitor cells and macrophages. Once the infection has decreased the disconnect between peripheral and central systems is reestablished and only microglia are present for the recovery and regrowth period.[41]

Aging

[edit]Microglia undergo a burst of mitotic activity during injury; this proliferation is followed by apoptosis to reduce the cell numbers back to baseline.[42] Activation of microglia places a load on the anabolic and catabolic machinery of the cells causing activated microglia to die sooner than non-activated cells.[42] To compensate for microglial loss over time, microglia undergo mitosis and bone marrow derived progenitor cells migrate into the brain via the meninges and vasculature.[42]

Accumulation of minor neuronal damage that occurs during normal aging can transform microglia into enlarged and activated cells.[43] These chronic, age-associated increases in microglial activation and IL-1 expression may contribute to increased risk of Alzheimer's disease with advancing age through favoring neuritic plaque formation in susceptible patients.[43] DNA damage might contribute to age-associated microglial activation. Another factor might be the accumulation of advanced glycation endproducts, which accumulate with aging.[43] These proteins are strongly resistant to proteolytic processes and promote protein cross-linking.[43]

Research has discovered dystrophic (defective development) human microglia. "These cells are characterized by abnormalities in their cytoplasmic structure, such as deramified, atrophic, fragmented or unusually tortuous processes, frequently bearing spheroidal or bulbous swellings."[42] The incidence of dystrophic microglia increases with aging.[42] Microglial degeneration and death have been reported in research on prion disease, schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease, indicating that microglial deterioration might be involved in neurodegenerative diseases.[42] A complication of this theory is the fact that it is difficult to distinguish between "activated" and "dystrophic" microglia in the human brain.[42]

In mice, it has been shown that CD22 blockade restores homeostatic microglial phagocytosis in aging brains.[44]

Clinical significance

[edit]

Microglia are the primary immune cells of the central nervous system, similar to peripheral macrophages. They respond to pathogens and injury by changing morphology and migrating to the site of infection/injury, where they destroy pathogens and remove damaged cells. As part of their response they secrete cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, and reactive oxygen species, which help to direct the immune response. Additionally, they are instrumental in the resolution of the inflammatory response, through the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Microglia have also been extensively studied for their harmful roles in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, as well as cardiac diseases, glaucoma, and viral and bacterial infections. There is accumulating evidence that immune dysregulation contributes to the pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), Tourette syndrome, and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS).[45]

Since microglia rapidly react to even subtle alterations in central nervous system homeostasis, they can be seen as sensors for neurological dysfunctions or disorders.[46] In the event of brain pathologies, the microglial phenotype is certainly altered.[46] Therefore, analyzing microglia can be a sensitive tool to diagnose and characterize central nervous system disorders in any given tissue specimen.[46] In particular, the microglial cell density, cell shape, distribution pattern, distinct microglial phenotypes and interactions with other cell types should be evaluated.[46]

Sensome genetics

[edit]The microglial sensome is a relatively new biological concept that appears to be playing a large role in neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration. The sensome refers to the unique grouping of protein transcripts used for sensing ligands and microbes. In other words, the sensome represents the genes required for the proteins used to sense molecules within the body. The sensome can be analyzed with a variety of methods including qPCR, RNA-seq, microarray analysis, and direct RNA sequencing. Genes included in the sensome code for receptors and transmembrane proteins on the plasma membrane that are more highly expressed in microglia compared to neurons. It does not include secreted proteins or transmembrane proteins specific to membrane bound organelles, such as the nucleus, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum.[47] The plurality of identified sensome genes code for pattern recognition receptors, however, there are a large variety of included genes. Microglial share a similar sensome to other macrophages, however they contain 22 unique genes, 16 of which are used for interaction with endogenous ligands. These differences create a unique microglial biomarker that includes over 40 genes including P2ry12 and HEXB. DAP12 (TYROBP) appears to play an important role in sensome protein interaction, acting as a signalling adaptor and a regulatory protein.[47]

The regulation of genes within the sensome must be able to change in order to respond to potential harm. Microglia can take on the role of neuroprotection or neurotoxicity in order to face these dangers.[48] For these reasons, it is suspected that the sensome may be playing a role in neurodegeneration. Sensome genes that are upregulated with aging are mostly involved in sensing infectious microbial ligands while those that are downregulated are mostly involved in sensing endogenous ligands.[47] This analysis suggests a glial-specific regulation favoring neuroprotection in natural neurodegeneration. This is in contrast to the shift towards neurotoxicity seen in neurodegenerative diseases.

The sensome can also play a role in neurodevelopment. Early-life brain infection results in microglia that are hypersensitive to later immune stimuli. When exposed to infection, there is an upregulation of sensome genes involved in neuroinflammation and a downregulation of genes that are involved with neuroplasticity.[49] The sensome's ability to alter neurodevelopment may however be able to combat disease. The deletion of CX3CL1, a highly expressed sensome gene, in rodent models of Rett syndrome resulted in improved health and longer lifespan.[50] The downregulation of Cx3cr1 in humans without Rett syndrome is associated with symptoms similar to schizophrenia.[51] This suggests that the sensome not only plays a role in various developmental disorders, but also requires tight regulation in order to maintain a disease-free state.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ginhoux F, Lim S, Hoeffel G, Low D, Huber T (2013). "Origin and differentiation of microglia". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 7: 45. doi:10.3389/fncel.2013.00045. PMC 3627983. PMID 23616747.

- ^ Lana D, Magni G, Landucci E, Wenk GL, Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Giovannini MG (September 2023). "Phenomic Microglia Diversity as a Druggable Target in the Hippocampus in Neurodegenerative Diseases". Int J Mol Sci. 24 (18) 13668. doi:10.3390/ijms241813668. PMC 10531074. PMID 37761971.

- ^ Dos Santos SE, Medeiros M, Porfirio J, Tavares W, Pessôa L, Grinberg L, et al. (June 2020). "Similar Microglial Cell Densities across Brain Structures and Mammalian Species: Implications for Brain Tissue Function". The Journal of Neuroscience. 40 (24): 4622–43. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2339-19.2020. PMC 7294795. PMID 32253358.

- ^ Filiano AJ, Gadani SP, Kipnis J (August 2015). "Interactions of innate and adaptive immunity in brain development and function". Brain Research. 1617: 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.07.050. PMC 4320678. PMID 25110235.

- ^ a b c Dermitzakis I, Manthou ME, Meditskou S, Tremblay MÈ, Petratos S, Zoupi L, et al. (March 2023). "Origin and Emergence of Microglia in the CNS-An Interesting (Hi)story of an Eccentric Cell". Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 45 (3): 2609–28. doi:10.3390/cimb45030171. PMC 10047736. PMID 36975541.

- ^ Kreutzberg GW (March 1995). "Microglia, the first line of defence in brain pathologies". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 45 (3A): 357–60. PMID 7763326.

- ^ Bushong EA, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH (January 2002). "Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains". The Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (1): 183–92. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00183.2002. PMC 6757596. PMID 11756501.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y, Kreutzberg GW (March 1995). "Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 20 (3): 269–87. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(94)00015-H. PMID 7550361. S2CID 22708728.

- ^ Dissing-Olesen L, Ladeby R, Nielsen HH, Toft-Hansen H, Dalmau I, Finsen B (October 2007). "Axonal lesion-induced microglial proliferation and microglial cluster formation in the mouse". Neuroscience. 149 (1): 112–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.037. PMID 17870248. S2CID 36995129.

- ^ Kierdorf and Prinz, J Clin Invest. 2017;127(9): 3201–09. doi:10.1172/JCI90602.

- ^ a b Cserép C, Pósfai B, Lénárt N, Fekete R, László ZI, Lele Z, et al. (January 2020). "Microglia monitor and protect neuronal function through specialized somatic purinergic junctions". Science. 367 (6477): 528–37. Bibcode:2020Sci...367..528C. doi:10.1126/science.aax6752. PMID 31831638. S2CID 209343260.

- ^ a b Nimmerjahn A (January 2020). "Monitoring neuronal health". Science. 367 (6477): 510–511. Bibcode:2020Sci...367..510N. doi:10.1126/science.aba4472. PMC 9291239. PMID 32001643.

- ^ Babeş VM (1892). "Certains caractères des lesions histologiques de la rage" [Certain characteristics of the histological lesions of rabies]. Annales de l'Institut Pasteur (in French). 6: 209–23.

- ^ Sierra A, de Castro F, Del Río-Hortega J, Rafael Iglesias-Rozas J, Garrosa M, Kettenmann H (November 2016). "The 'Big-Bang' for modern glial biology: Translation and comments on Pío del Río-Hortega 1919 series of papers on microglia". Glia. 64 (11) (published 2016-09-16): 1801–40. doi:10.1002/glia.23046. PMID 27634048. S2CID 3712733.

- ^ del Río Hortega P, Penfield W (1892). "Cerebral Cicatrix: the Reaction of Neuroglia and Microglia to Brain Wounds". Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 41: 278–303.

- ^ del Rio-Hortega F (1937). "Microglia". Cytology and Cellular Pathology of the Nervous System: 481–534.

- ^ Lawson, Perry, Dri, Gordon (1990). "Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain". Neuroscience. 39 (1): 151–170. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-W. PMID 2089275.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fernandez-Arjona M.D.M., Grondona J.M., Fernandez-Llebrez P. , Lopez-Avalos M.D. (2019). "Microglial morphometric parameters correlate with the expression level of IL-1beta, and allow identifying different activated morphotypes". Front Cell Neurosci. 13 472. doi:10.3389/fncel.2019.00472. PMC 6824358. PMID 31708746.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Verkhratsky A, Butt A (2013). Glial physiology and pathophysiology. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-40205-4.[page needed]

- ^ Peter, Berki; Csaba, Cserep; Zsuzsanna, Környei (2024). "Microglia contribute to neuronal synchrony despite endogenous ATP-related phenotypic transformation in acute mouse brain slices". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 5402. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.5402B. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-49773-1. PMC 11208608. PMID 38926390.

- ^ a b c d e f g Aloisi F (November 2001). "Immune function of microglia". Glia. 36 (2): 165–79. doi:10.1002/glia.1106. PMID 11596125. S2CID 25410282.

- ^ a b c Christensen RN, Ha BK, Sun F, Bresnahan JC, Beattie MS (July 2006). "Kainate induces rapid redistribution of the actin cytoskeleton in ameboid microglia". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 84 (1): 170–81. doi:10.1002/jnr.20865. PMID 16625662. S2CID 34491558.

- ^ Davis EJ, Foster TD, Thomas WE (1994). "Cellular forms and functions of brain microglia". Brain Research Bulletin. 34 (1): 73–78. doi:10.1016/0361-9230(94)90189-9. PMID 8193937. S2CID 22596219.

- ^ Eggen BJ, Raj D, Hanisch UK, Boddeke HW (September 2013). "Microglial phenotype and adaptation". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 8 (4): 807–23. doi:10.1007/s11481-013-9490-4. PMID 23881706. S2CID 15283939.

- ^ Lan X, Han X, Li Q, Yang QW, Wang J (July 2017). "Modulators of microglial activation and polarization after intracerebral haemorrhage". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 13 (7): 420–33. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2017.69. PMC 5575938. PMID 28524175.

- ^ Jelinek HF, Karperien A, Bossomaier T, Buchan A (1975). "Differentiating grades of microglia activation with fractal analysis" (PDF). Complexity International. 12 (18): 1713–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- ^ a b Ferrer I, Bernet E, Soriano E, del Rio T, Fonseca M (1990). "Naturally occurring cell death in the cerebral cortex of the rat and removal of dead cells by transitory phagocytes". Neuroscience. 39 (2): 451–58. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(90)90281-8. PMID 2087266. S2CID 23457378.

- ^ a b Takashi Koizumi; Danielle Kerkhofs; Toshiki Mizuno; Harry WM Steinbusch; Sebastien Foulquier (4 December 2019). "Vessel-Associated Immune Cells in Cerebrovascular Diseases: From Perivascular Macrophages to Vessel-Associated Microglia". Front. Neurosci. 13 1291. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.01291. PMC 6904330. PMID 31866808.

- ^ Morris GP, Foster CG, Courtney JM, Collins JM, Cashion JM, Brown LS, et al. (August 2023). "Microglia directly associate with pericytes in the central nervous system". Glia. 71 (8): 1847–69. doi:10.1002/glia.24371. PMC 10952742. PMID 36994950.

- ^ Morris, Gary P.; Foster, Catherine G.; Sutherland, Brad A.; Grubb, Søren (2024). "Microglia contact cerebral vasculature through gaps between astrocyte endfeet". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 44 (12): 1472–1486. doi:10.1177/0271678X241280775. PMC 11751324. PMID 39253821.

- ^ Chung WS, Welsh CA, Barres BA, Stevens B (November 2015). "Do glia drive synaptic and cognitive impairment in disease?". Nature Neuroscience. 18 (11): 1539–45. doi:10.1038/nn.4142. PMC 4739631. PMID 26505565.

- ^ Galloway DA, Phillips AE, Owen DR, Moore CS (2019). "Phagocytosis in the Brain: Homeostasis and Disease". Frontiers in Immunology. 10 790. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00790. PMC 6477030. PMID 31040847.

- ^ Wolf A, Herb M, Schramm M, Langmann T (June 2020). "The TSPO-NOX1 axis controls phagocyte-triggered pathological angiogenesis in the eye". Nature Communications. 11 (1) 2709. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.2709W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16400-8. PMC 7264151. PMID 32483169.

- ^ Banno M, Mizuno T, Kato H, Zhang G, Kawanokuchi J, Wang J, et al. (February 2005). "The radical scavenger edaravone prevents oxidative neurotoxicity induced by peroxynitrite and activated microglia". Neuropharmacology. 48 (2): 283–90. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.10.002. PMID 15695167. S2CID 25545853.

- ^ Soteros BM, Sia GM (November 2021). "Complement and microglia dependent synapse elimination in brain development". WIREs Mechanisms of Disease. 14 (3) e1545. doi:10.1002/wsbm.1545. PMC 9066608. PMID 34738335.

- ^ Ritter MR, Banin E, Moreno SK, Aguilar E, Dorrell MI, Friedlander M (December 2006). "Myeloid progenitors differentiate into microglia and promote vascular repair in a model of ischemic retinopathy". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (12): 3266–76. doi:10.1172/JCI29683. PMC 1636693. PMID 17111048.

- ^ Cserép C, Schwarcz AD, Pósfai B, László ZI, Kellermayer A, Környei Z, et al. (September 2022). "Microglial control of neuronal development via somatic purinergic junctions". Cell Reports. 40 (12) 111369. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111369. PMC 9513806. PMID 36130488. S2CID 252416407.

- ^ Stanley ER, Chitu V (June 2014). "CSF-1 receptor signaling in myeloid cells". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (6) a021857. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021857. PMC 4031967. PMID 24890514.

- ^ Ginhoux F, Prinz M (July 2015). "Origin of microglia: current concepts and past controversies". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (8) a020537. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a020537. PMC 4526747. PMID 26134003.

- ^ Zhu H, Wang Z, Yu J, Yang X, He F, Liu Z, et al. (July 2019). "Role and mechanisms of cytokines in the secondary brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage". Progress in Neurobiology. 178 101610. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.03.003. PMID 30923023. S2CID 85495400.

- ^ Gehrmann J (1996). "Microglia: a sensor to threats in the nervous system?". Research in Virology. 147 (2–3): 79–88. doi:10.1016/0923-2516(96)80220-2. PMID 8901425.

- ^ a b c d e f g Streit WJ (September 2006). "Microglial senescence: does the brain's immune system have an expiration date?". Trends in Neurosciences. 29 (9): 506–10. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.07.001. PMID 16859761. S2CID 8874596.

- ^ a b c d Mrak RE, Griffin WS (March 2005). "Glia and their cytokines in progression of neurodegeneration". Neurobiology of Aging. 26 (3): 349–54. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.010. PMID 15639313. S2CID 33152515.

- ^ Pluvinage JV, Haney MS, Smith BA, Sun J, Iram T, Bonanno L, et al. (April 2019). "CD22 blockade restores homeostatic microglial phagocytosis in ageing brains". Nature. 568 (7751): 187–92. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..187P. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1088-4. PMC 6574119. PMID 30944478.

- ^ Frick L, Pittenger C (2016). "Microglial Dysregulation in OCD, Tourette Syndrome, and PANDAS". Journal of Immunology Research. 2016 8606057. doi:10.1155/2016/8606057. PMC 5174185. PMID 28053994.

- ^ a b c d Schwabenland M, Brück W, Priller J, Stadelmann C, Lassmann H, Prinz M (December 2021). "Analyzing microglial phenotypes across neuropathologies: a practical guide". Acta Neuropathologica. 142 (6) (published October 2021): 923–36. doi:10.1007/s00401-021-02370-8. PMC 8498770. PMID 34623511.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c Hickman SE, Kingery ND, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky ML, Wang LC, Means TK, El Khoury J (December 2013). "The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing". Nature Neuroscience. 16 (12): 1896–905. doi:10.1038/nn.3554. PMC 3840123. PMID 24162652.

- ^ Block, ML, Zecca, L & Hong, JS. "Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 57–69 (2007).

- ^ Ji P, Schachtschneider KM, Schook LB, Walker FR, Johnson RW (May 2016). "Peripheral viral infection induced microglial sensome genes and enhanced microglial cell activity in the hippocampus of neonatal piglets". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 54: 243–51. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2016.02.010. PMC 4828316. PMID 26872419.

- ^ Horiuchi M, Smith L, Maezawa I, Jin LW (February 2017). "CX3CR1 ablation ameliorates motor and respiratory dysfunctions and improves survival of a Rett syndrome mouse model". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 60: 106–16. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2016.02.014. PMC 5531048. PMID 26883520.

- ^ Bergon A, Belzeaux R, Comte M, Pelletier F, Hervé M, Gardiner EJ, et al. (October 2015). "CX3CR1 is dysregulated in blood and brain from schizophrenia patients" (PDF). Schizophrenia Research. 168 (1–2): 434–43. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.010. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_49794. PMID 26285829. S2CID 205073822.

Further reading

[edit]- Rock RB, Gekker G, Hu S, Sheng WS, Cheeran M, Lokensgard JR, Peterson PK (October 2004). "Role of microglia in central nervous system infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 17 (4): 942–64, table of contents. doi:10.1128/CMR.17.4.942-964.2004. PMC 523558. PMID 15489356.

- Han X, Li Q, Lan X, El-Mufti L, Ren H, Wang J (September 2019). "Microglial Depletion with Clodronate Liposomes Increases Proinflammatory Cytokine Levels, Induces Astrocyte Activation, and Damages Blood Vessel Integrity". Molecular Neurobiology. 56 (9): 6184–96. doi:10.1007/s12035-019-1502-9. PMC 6684378. PMID 30734229.

External links

[edit]- Microglia information, videos & resources at microglia.info

- Microglia home page at microglia.net

- "Creeping into your Head – A Brief Introduction to Microglia" – A Review from the Science Creative Quarterly

- "Immune Scavengers Target Alzheimer's Plaques". April 6, 2007.

- The Department of Neuroscience at Wikiversity

- NIF Search – Microglial Cell via the Neuroscience Information Framework