Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Georgia General Assembly

View on Wikipedia

The Georgia General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is bicameral, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Key Information

Each of the General Assembly's 236 members serve two-year terms and are directly elected by constituents of their district.[1][2] The Constitution of Georgia vests all legislative power with the General Assembly. Both houses have similar powers, though each has unique duties as well.[1] For example, the origination of appropriations bills only occurs in the House, while the Senate is tasked with confirmation of the governor's appointments.[1]

The General Assembly meets in the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta.

History

[edit]The General Assembly, which is the legislative branch of the state's government, was created in 1777 during the American Revolution—it is older than the United States Congress. During its existence the Assembly has moved four different times when the state capital changed its location. The first location of the Assembly was Savannah, then Augusta and Louisville, moving from there to Milledgeville, and finally to Atlanta in 1868.[3]

The General Assembly in Savannah

[edit]By January 1777 Savannah had become the capital of Georgia—when the former colony declared independence from Britain. The legislature, then a unicameral body, met there in 1777–1778—retreating to Augusta when the British captured the city. They were not in Augusta long before it was captured by the British in 1779. Augusta changed hands three times during the war, finally returning to American possession in July 1781. They stayed in Augusta until the British left Savannah in May 1782 and the legislature returned to the capital.[3]

Move to Augusta

[edit]Between 1783 and 1785, the Georgia General Assembly met in both Savannah and Augusta—moving from there when tensions arose between the two cities, causing then Governor Lyman Hall to officially reside in both places. On February 22, 1785, the General Assembly held its last meeting in Savannah—Augusta had become the official capital due to pressure from the general populace to have their capital in the center of the state.[3]

On to Louisville

[edit]As the population dispersed—shifting the geographic center, it was determined that the state's capital needed to move as well. A commission was appointed by the legislature in 1786 to find a suitable location that was central to the new demography. The commission recommended Louisville, which would become Georgia's first planned capital and would hold her first capitol building. Due to the fact that the capital would have to be built from the ground up, and because of numerous construction delays, it took a decade to build the city. The name Louisville was chosen by the General Assembly in honor of King Louis XVI for France's aid during the Revolutionary War.

The new state house, a two-story 18th century Gregorian building of red brick, was completed in 1796. The Legislature designated Louisville the "permanent seat" of Georgia's government. Yet, further western expansion created the need for another new state capital. The capitol building was purchased by Jefferson County and used as a courthouse, but the building had to be torn down because it became unsound. A plaque marks the location of the old Capitol.[3]

The Assembly arrives in Milledgeville

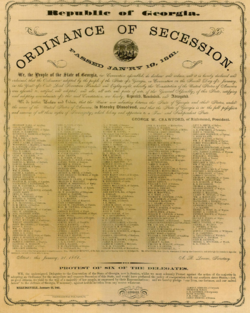

[edit]| Ordinance of Secession | |

|---|---|

Facsimile of the 1861 Ordinance of Secession signed by 293 delegates to the Georgia Secession Convention at the statehouse in Milledgeville, Georgia January 21, 1861. | |

| Full text | |

In 1804, the state government decided that yet another capital, would be needed. Subsequently, an act was passed authorizing construction of a new capital city on 3,240 acres (13 km2) in the area currently known as Baldwin County. The city was named Milledgeville in honor of Governor John Milledge.

The new Capitol took two years to complete and was a brick construction in the Gothic Revival style. The legislature convened The Georgia Secession Convention of 1861 in the Milledgeville statehouse on January 16, 1861. On January 19, delegates voted for Georgia to secede from the Union—208 in favor with 89 against—drafting a new constitution, and declaring the state an independent Republic.

On January 21, Assembly delegates (secessionists finishing with a slight majority of delegates)[4] celebrated their decision by a public signing of the Ordinance of Secession outside of the State Capitol. Later that year, the legislature also voted to send $100,000 to South Carolina for "the relief of Charlestonians" who suffered a disastrous fire in December 1861. With General Sherman's approach, the members of the General Assembly adjourned in fall 1864, reconvening briefly in Macon in 1865. As the American Civil War came to a close with the federal government in military control of Georgia, the legislature reconvened at the Capitol in Milledgeville.[3]

Atlanta

[edit]In 1867, Major General John Pope, military governor of Georgia, called for an assembly in Atlanta to hold a constitutional convention. At that time Atlanta officials moved once again to have the city designated as Georgia's state capital, donating the property where Atlanta's first city hall was constructed. The constitutional convention agreed and the people voted to ratify the decision on April 20, 1868. The Georgia General Assembly first convened in Atlanta on July 4, 1868.

In 1884, the legislature appropriated one million dollars to build a new State Capitol. Construction began October 26, 1884, and the building was completed (slightly under budget) and occupied on June 15, 1889.[3]

Notably, the dome atop the capitol building is plated with real gold, most of which came from the Dahlonega, Georgia area.[5] The roofing gives rise to local colloquialisms—for instance, if one knowledgeable Georgian wanted to ask another what the General Assembly was doing, he might ask what was happening "under the gold dome."[6]

Organization and procedure of the General Assembly

[edit]The General Assembly meets in regular session on the second Monday in January for no longer than 40 legislative (rather than calendar) days each year. Neither the House nor the Senate can adjourn during a regular session for longer than three days or meet in any place other than the state capitol without the other house's consent. The legislative session usually lasts from January until late March or early April. When the General Assembly is not sitting, legislative committees may still meet to discuss specific issues. In cases of emergency, the Governor can summon a special session of the Assembly. Days in special session do not count towards the 40-day constitutional limit.

Committees

[edit]Both the House and Senate are organized into various legislative committees. All bills introduced in the General Assembly will be referred to at least one committee. Committee chairs usually come from the majority party. Committee chairs determine the business of the committee, including which bills get a hearing.

Rules of procedure, employees and interim committees

[edit]Each house of the General Assembly may determine procedural rules governing its own employees. The General Assembly as a whole, or each house separately, has the ability to create interim committees.

At the beginning of each two-year term, the House elects a speaker, who is always from the majority party. Unlike in the federal House of Representatives, the speaker usually presides over sittings of the House. There is also a speaker pro tempore, who presides in the absence of the speaker.

The Lieutenant Governor of Georgia is the ex officio president of the State Senate. The lieutenant governor is elected for a four-year term in a statewide vote along with the governor. The lieutenant governor does not have the power to introduce legislation.

Oath of office

[edit]Before taking office senators and representatives must swear (or affirm) an oath—stipulated by state law.

Legislative procedure

[edit]A majority of the members to which each house is entitled constitutes a quorum to transact business. A smaller number may adjourn from day to day and compel the presence of its absent members. In order for a bill to become law, it must be passed by both chambers of the General Assembly, and receive the governor's signature. In each chamber, the number of votes required to pass a bill is determined according to the number of seats in the chamber, not merely the number of votes cast. Therefore, a bill must receive 91 votes in the House (a majority of its membership) and 29 votes in the Senate, regardless of the number of legislators voting. In the case of a tie, the presiding officer of each chamber may cast the deciding vote.

Some motions require more than an absolute majority to pass. A resolution to amend the state constitution, for instance, requires a two-thirds vote in both chambers (121 votes in the House and 38 votes in the Senate).

All senators and representatives are entitled to introduce bills and resolutions. Bills are intended to have the force of law, while resolutions may or may not have any practical effect. Bills and resolutions are referred to a legislative committee by the presiding officer as soon as they are introduced. The presiding officer has discretion to refer a bill to any committee he or she chooses, although the chamber may vote to move a bill to a different committee.

Committee chairs determine which bills will be heard in committee. Bills that do not get a committee hearing cannot proceed, and the majority of bills die in committee this way. Because most committee chairs are from the majority party, bills that are introduced by members of the majority are much more likely to be heard. The vast majority of legislation considered by the Assembly is introduced by the majority party. Committees will hear testimony from a bill's sponsor, as well as experts in the public and private sectors and concerned citizens. Members of the committee may ask questions of the sponsor. Committees usually amend bills under their consideration; an amended version of a bill is known as a "substitute." Once the committee is done debating, it will vote on the bill, as well as any proposed amendments. If the bill is approved, it is transmitted to the Committee on Rules.

Both the House and Senate have a Rules committee. The House Committee on Rules meets early in the morning on most legislative days to determine which bills will get a floor vote that day. Power in House Rules is highly centralized, and the committee usually acts as a rubber stamp for decisions already made by the chairperson, the speaker, and even the governor. The Senate Committee on Rules meets after each legislative day, to determine the agenda for the next legislative day.

For the first 28 days in a legislative session, the House and Senate only consider legislation introduced by their own members. After the 28th day, bills passed by one chamber will "cross over" to the other, hence why the day is known as "Crossover Day." After Crossover Day, no new bills will be considered. If a bill, after having crossed over to the other chamber, is amended in committee on the floor, it will have to return to the original chamber for final approval. Further amendments may be made, and the bill will move back and forth until both chambers agree. If the two chambers cannot agree on the final version of a bill by the end of the session, the bill is not passed.

Vacancies

[edit]Whenever a vacancy occurs in the General Assembly, an event that occurs whenever a member dies, resigns, or moves from the district from which he was elected, it is filled according to Georgia law and the Constitution.[7] If the vacancy occurs anytime prior to the end of the legislative session in the second year of a term, the governor must issue a writ of special election within ten days of the vacancy occurring, and, if the vacancy occurs after the end of the legislative session in the second year of a term, then the governor may choose to issue a writ of special election. But, if the vacancy exists at the time that an extraordinary session is called, then the governor must issue a writ of special election within 2 days after the call for the extraordinary session, and, if the vacancy occurs after the call but before the special session has concluded, then the governor must issue a writ of special election within 5 days of the occurrence. In each case, the writ of special election must designate a day on which the election will be held, which must be no less than 30 days and no more than 60 days after the governor issues the writ.[8]

Salaries

[edit]Members of the General Assembly receive salaries provided by law, so long as that salary does not increase before the end of the term during which the increase becomes effective. Members of the Georgia General Assembly currently earn $17,000 a year.[9]

Election and returns; disorderly conduct

[edit]Each house holds the responsibility of judging the election, returns, and qualifications of its own members. Also, each house has the power to punish its own members for disorderly misconduct. Punishments for such conduct include:

- censure

- fine

- imprisonment

- expulsion

However, no member may be expelled except upon a two-thirds vote of the house in which he or she sits.

Contempt

[edit]When a person is guilty of contempt, the individual may be imprisoned if ordered by either the House or the Senate.

Elections by either house

[edit]All elections of the General Assembly are to be recorded. The recorded vote then appears in the journal of each house.

Open meetings

[edit]Sessions of the General Assembly, including committee meetings, are open to the public except when either house makes an exception.

Legislative history

[edit]The General Assembly does not publish reports and does not keep bill files. Major legislation is discussed in detail in the Peach Sheets,[10] a student-written part of Georgia State University College of Law's Law Review. Recent Peach Sheet articles are available in an online archive. Otherwise, Peach Sheets articles should be included in the Georgia State Law Review databases on Lexis, Westlaw and HeinOnline.[11]

Composition

[edit]The Georgia General Assembly began in 1777 as a body consisting of the lower House of Assembly to which counties elected two members each, and an Executive Council, which included a councillor elected by their respective Assembly delegation. After the enactment of the Georgia Constitution of 1789, the body was changed to a bicameral legislature of a Senate and House of Representatives, both to be directly elected. From 1789 to 1795, senators were elected every three years, and after the enactment of the May 1795 Constitution, senators were elected annually to one-year terms. Senators were moved to two-terms after December 5, 1843.

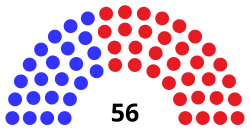

It is now made up of a Senate (the upper house) and a House of Representatives (the lower house). The Senate has 56 members while the House of Representatives has 180. Members from each body serve for two years, but have no limit to the number of times they can be re-elected. Both senators and representatives are elected from their constituents' districts.

Qualifications for election

[edit]The Georgia Constitution stipulates that members of the Senate must be citizens of the United States, at least 25 years old, a citizen of the state of Georgia at least two years, and a legal resident of the district the senator was elected to. Members of the House of Representatives must be citizens of the United States, at least 21 years old, a Georgia citizen for at least two years, and a legal resident of the district the representative was elected for at least one year.

Disqualifications

[edit]According to the Georgia Constitution Article III Section II Paragraph IV:[12]

- No person on active duty with any branch of the armed forces of the United States shall have a seat in either house unless otherwise provided by law.

- No person holding any civil appointment or office having any emolument annexed thereto under the United States, this state, or any other state shall have a seat in either house.

- No Senator or Representative shall be elected by the General Assembly or appointed by the Governor to any office or appointment having any emolument annexed thereto during the time for which such person shall have been elected unless the Senator or Representative shall first resign the seat to which elected; provided, however, that, during the term for which elected, no Senator or Representative shall be appointed to any civil office which has been created during such term.

Officers

[edit]The presiding officer of the Senate is the President of the Senate or Lieutenant Governor. Like the United States Senate, a President Pro Tempore is elected by the Senate from among its members. The President Pro Tempore acts as president in case of the temporary disability of the President. In case of the death, resignation, or permanent disability of the President or in the event of the succession of the President to the executive power, the President Pro Tempore becomes President. The Senate also has as an officer the Secretary of the Senate.

The House of Representatives elects its own Speaker and a Speaker Pro Tempore. The Speaker Pro Tempore becomes Speaker in case of the death, resignation, or permanent disability of the Speaker. The Speaker Pro Tempore serves until a new Speaker is elected. The House also has as an officer the Clerk of the House of Representatives.

Historic composition

[edit]The 1866 Constitution called for 22 seats in the Senate and 175 seats in the House. The 1877 Constitution expanded the Senate to 44 seats while keeping 175 members in the House.

Powers and privileges

[edit]Article III Section VI of the Georgia State Constitution specifies the powers given to the Georgia General Assembly.[12] Paragraph I states, "The General Assembly shall have the power to make all laws not inconsistent with this Constitution, and not repugnant to the Constitution of the United States, which it shall deem necessary and proper for the welfare of the state." Moreover, the powers the Constitution gives the Assembly include land use restrictions to protect and preserve the environment and natural resources; the creation, use and disciplining through court martial of a state militia which would be under the command of the Governor of Georgia acting as commander-in-chief (excepting times when the militia is under Federal command); The power to expend public money, to condemn property, and to zone property; The continuity of state and local governments during times of emergency; state participation in tourism. The use, control and regulation of outdoor advertising within the state.

Limitation of powers

[edit]Paragraph V of Article III Section VI states that:

- The General Assembly shall not have the power to grant incorporation to private persons but shall provide by general law the manner in which private corporate powers and privileges may be granted.

- The General Assembly shall not forgive the forfeiture of the charter of any corporation existing on August 13, 1945, nor shall it grant any benefit to or permit any amendment to the charter of any corporation except upon the condition that the acceptance thereof shall operate as a novation of the charter and that such corporation shall thereafter hold its charter subject to the provisions of this Constitution.

- The General Assembly shall not have the power to authorize any contract or agreement which may have the effect of or which is intended to have the effect of defeating or lessening competition, or encouraging a monopoly, which are hereby declared to be unlawful and void.

- The General Assembly shall not have the power to regulate or fix charges of public utilities owned or operated by any county or municipality of this state, except as authorized by this Constitution.

- No municipal or county authority which is authorized to construct, improve, or maintain any road or street on behalf of, pursuant to a contract with, or through the use of taxes or other revenues of a county or municipal corporation shall be created by any local Act or pursuant to any general Act nor shall any law specifically relating to any such authority be amended unless the creation of such authority or the amendment of such law is conditioned upon the approval of a majority of the qualified voters of the county or municipal corporation affected voting in a referendum thereon. This subparagraph shall not apply to or affect any state authority.

Privileges of members

[edit]Members of the Georgia General Assembly maintain two important privileges during their time in office. First, no member of either house of the Assembly can be arrested during sessions of the General Assembly or during committee meetings except in cases of treason, felony, or "breach of the peace". Also, members are not liable for anything they might say in either the House or the Senate or in any committee meetings of both.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c georgia.gov - Legislature Archived April 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. georgia.gov. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ Georgia General Assembly Archived July 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. georgiaencyclopedia.org. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f The Capitalization of Georgia Archived April 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. sos.state.ga.us. Retrieved February 5, 2007.

- ^ "Georgia Secession Convention of 1861". georgiaencyclopedia.org. Georgia Humanities. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Georgia State Capitol". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ "Under the Gold Dome | Legislative Preview 2017". ajc. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ Ga. Const. Art. 3, § 4, ¶ V. http://sos.ga.gov/admin/files/Constitution_2013_Final_Printed.pdf

- ^ O.C.G.A. § 21-2-544. http://web.lexisnexis.com/research/xlink?app=00075&view=full&interface=1&docinfo=off&searchtype=get&search=O.C.G.A.+%A7+21-2-544[permanent dead link]

- ^ Salzer, James. "Cost of politics puts off potential candidates". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Peach Sheets. digitalarchive.gsu.edu. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Zimmerman's Research Guide". Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Georgia Constitution Article III Section II Paragraph IV Archived 2007-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. cviog.uga.edu. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

References

[edit]- Cobb, James C. Georgia Odyssey. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

- Fleischman, Arnold, and Pierannunzi, Carol. Politics in Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

- Grant, Chris. Our Arc of Constancy: The Georgia General Assembly, 250 Years of Effective Representation for all Georgians. Atlanta: Georgia Humanities Council, 2001.

External links

[edit]- Georgia General Assembly website

- Georgia Encyclopedia article Archived July 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- georgia.gov - Legislature

- The Capitalization of Georgia Archived April 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

Georgia General Assembly

View on GrokipediaOverview and Constitutional Role

Establishment and Purpose

The Georgia General Assembly traces its origins to Georgia's first state constitution, ratified on February 5, 1777, which established a unicameral legislature vested with the state's legislative powers.[11] This body, elected annually by free white male inhabitants aged 21 or older who owned at least 50 acres of land or equivalent property, convened for the first time in Savannah on February 13, 1778, to enact laws, levy taxes, and manage wartime finances amid the American Revolution.[12] The 1777 framework concentrated authority in this single chamber to ensure rapid decision-making in a frontier state transitioning from colonial rule, reflecting influences from Pennsylvania's unicameral model while separating powers into legislative, executive, and judicial branches.[13] A revised constitution adopted in 1789 transformed the General Assembly into a bicameral institution, introducing a Senate and House of Representatives to enhance checks on legislative impulses and align more closely with the federal model established by the U.S. Constitution.[14] The Senate, with members elected for two-year terms from districts apportioned by population, served as an upper house for deliberation, while the House provided broader representation.[15] This structure has endured through subsequent constitutional revisions, including the current 1983 document, which explicitly vests "the legislative power of the state" in the General Assembly.[16] The primary purpose of the General Assembly is to enact statutes governing state affairs, appropriate funds for the annual operating budget, and exercise oversight over executive functions, such as confirming appointments and impeaching officials when necessary.[5][7] It convenes annually on the second Monday in January for up to 40 legislative days, focusing on policy priorities like taxation, education funding, and infrastructure, while maintaining fiscal conservatism through biennial budgeting cycles.[16] This role underscores its function as the people's elected forum for balancing competing interests via debate and compromise, distinct from direct democracy or executive fiat.[4]Bicameral Framework and Size

The Georgia General Assembly operates as a bicameral legislature, with legislative authority vested in two distinct chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives, as specified in Article III, Section I of the 1983 Georgia Constitution.[16] This structure mirrors the U.S. Congress, providing checks and balances within the state lawmaking process, where bills typically require approval from both houses before advancing to the governor.[16] The Senate consists of 56 members, each elected from single-member districts apportioned based on population decennial census data, with the constitutional limit set at no fewer than 54 nor more than 56 senators.[16] All senators serve two-year terms without term limits.[17] The House of Representatives comprises 180 members, also elected from single-member districts redrawn every ten years following the federal census, with the constitution mandating no fewer than 180 representatives.[16] House members likewise serve two-year terms.[18] This configuration results in a total legislative body of 236 members, making Georgia's General Assembly one of the larger state legislatures in the United States by membership size.[3]Historical Evolution

Colonial Origins and Formation (1777–1789)

Prior to independence, Georgia operated under a royal colonial government established by the Charter of 1732, which evolved into a bicameral structure by 1752 featuring an appointed governor, an appointed council serving as the upper house, and an elected Commons House of Assembly as the lower house.[4] The Commons House, first convened in 1755, consisted of representatives elected by freeholders possessing at least fifty acres of land or a town lot, reflecting limited franchise typical of colonial assemblies.[4] This body handled local legislation, taxation, and grievances against royal authority, but its powers were checked by the governor's veto and the crown's oversight.[19] As tensions with Britain escalated during the American Revolution, Georgia's patriots formed extralegal bodies including a Council of Safety in 1775 and a Provincial Congress in 1776 to coordinate resistance, bypassing royal institutions amid divided loyalties in the colony.[20] The Provincial Congress, convened in April 1776, called for a constitutional convention to establish independent governance, aligning with the Continental Congress's recommendations.[12] This convention assembled on October 1, 1776, in Savannah and, after intermittent sessions, adopted Georgia's first state constitution on February 5, 1777.[21] The document vested legislative authority in a unicameral House of Assembly, comprising representatives elected annually from parishes and counties by white male inhabitants aged twenty-one or older who met minimal residency and property qualifications, approximating broad suffrage for the era.[11] This assembly held extensive powers to enact laws for the state's order and welfare, subject to few checks, with an elected executive president lacking veto authority.[13] The House of Assembly convened its first session under the new constitution in 1778, but British occupation of Georgia from late 1778 to July 1782 disrupted operations, forcing patriot legislators into exile or guerrilla resistance.[19] Post-liberation, the assembly reconvened in Augusta in 1782, addressing reconstruction, debt, and land distribution while navigating factional disputes between radicals and moderates.[19] By the mid-1780s, criticisms mounted over the 1777 constitution's imbalances, including an overpowered legislature, weak executive, and absence of explicit separation of powers, prompting calls for reform amid economic instability and Shays'-like debtor unrest.[12] In response, a convention convened in Savannah on October 13, 1788, and adopted a revised constitution on May 14, 1789, ratified by popular vote.[12] This framework transformed the legislature into a bicameral General Assembly, explicitly styled as such, comprising a Senate of ten members elected every three years from districts and a House of Representatives with members elected annually, both drawing from property-qualified white male voters.[22] The change aimed to moderate legislative dominance through divided powers, introduce a stronger governor with veto rights, and establish a judiciary, reflecting influences from the recently ratified U.S. Constitution while retaining state-specific provisions like parish-based representation.[12] The bicameral structure has endured, marking the formal origin of the modern Georgia General Assembly's organization.[15]19th-Century Developments and Capital Shifts

In the early 19th century, the Georgia General Assembly addressed the need for a more centrally located capital as the state's population expanded inland from coastal areas. Following the brief tenure of Louisville as capital from 1796 to 1802, the Assembly passed legislation in 1804 designating Milledgeville in Baldwin County as the new seat of government, with construction of the capitol building completed by 1807.[23] This move facilitated better access for upcountry representatives and symbolized the shift toward interior governance.[23] Throughout the antebellum period, the bicameral General Assembly convened annual sessions in November and December in Milledgeville, enacting laws to support economic expansion, including charters for banks and early railroads that connected the state.[24] The legislature's structure remained stable, with the House of Representatives and Senate handling bills on infrastructure, education, and agriculture amid rapid territorial growth following the Louisiana Purchase influences and Creek land cessions.[4] During the Civil War era, Milledgeville hosted critical deliberations, including the secession convention in January 1861, where delegates ratified Georgia's Ordinance of Secession on January 19, aligning the state with the Confederacy.[4] Post-war Reconstruction prompted further change; in 1868, under the new state constitution, the General Assembly ratified the relocation of the capital to Atlanta following a public referendum that favored the move by a vote of 89,007 to 71,309.[23] Atlanta's selection reflected its emergence as a railroad hub and industrial center, donated land for the capitol, and represented the "New South" in contrast to Milledgeville's association with the antebellum era.[23] This permanent shift marked the end of 19th-century capital relocations and positioned the Assembly in Georgia's growing economic core.[4]Civil War, Reconstruction, and 20th-Century Reforms

In the prelude to the Civil War, the Georgia General Assembly responded to Abraham Lincoln's election by appropriating $1 million for state defense on November 16, 1860, and authorizing Governor Joseph E. Brown to raise 10,000 troops two days later.[25] The Assembly endorsed secession by a vote of 208 to 89, prompting a convention that adopted the Ordinance of Secession on January 19, 1861, making Georgia the fifth state to leave the Union. During the war, the legislature convened annual sessions in Milledgeville, passing acts to support the Confederate effort, including an extra session in Macon after adjourning in fall 1864 amid General William T. Sherman's advance.[26] Following the war's end in 1865, the General Assembly ratified the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery in early December, under President Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction plan.[27] Unlike other former Confederate states, Georgia avoided enacting stringent Black Codes, instead passing measures granting persons of color—defined as those with one-eighth African blood—rights to contract, sue, inherit, and own property, though with restrictions on testimony against whites and other limitations.[28][27] Congressional Reconstruction imposed military rule in 1867, leading to a new state constitution in 1868 and the election of 32 African American legislators, who were promptly expelled by Democratic majorities on grounds of ineligibility despite meeting property and literacy requirements.[29] A total of 69 African Americans served in the legislature during this period, advocating for education and civil rights before their ouster.[30] Georgia's readmission to the Union on July 15, 1870, required ratifying the Fifteenth Amendment and seating black legislators, which the Assembly did amid ongoing political turmoil.[31] Democratic "Redeemers" regained control in late October 1871 through elections, leveraging intimidation and violence—including Ku Klux Klan activities—to dominate both legislative houses and end Republican governance.[32][30] In the 20th century, the General Assembly maintained rural-dominated apportionment to curb urban influence, exemplified by the county unit system in Democratic primaries, which allocated votes by county size rather than population, effectively diluting city dwellers' power until its invalidation as unconstitutional in Gray v. Sanders (1963).[33] Federal mandates under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and one-person, one-vote rulings compelled reapportionment reforms, shifting toward population-based districts and expanding legislative representation for growing metropolitan areas like Atlanta.[34] These changes professionalized operations, extended session lengths, and integrated standing committees, adapting the body to modern governance demands while dismantling Jim Crow-era electoral barriers.[35]Transition to Atlanta and Modern Operations

The Georgia General Assembly's transition to Atlanta occurred amid Reconstruction following the Civil War. The 1867–1868 Constitutional Convention, held under Union military governance, relocated the state capital from Milledgeville to Atlanta on a temporary basis, citing Atlanta's centrality, railroad infrastructure, and reduced risk of Confederate resistance compared to the former capital.[36] [37] This shift brought the General Assembly's sessions to Atlanta starting in 1868, initially convening in the city's overcrowded hall that doubled as municipal offices.[38] The 1868 state constitution formalized Atlanta's status as the permanent seat of government, mandating that the General Assembly operate from there onward.[39] [4] This relocation reflected Atlanta's postwar economic resurgence as a transportation and commercial hub, displacing Milledgeville's historical precedence established in 1804.[23] By the late 1870s, amid ongoing debates, the legislature affirmed the move, with Atlanta donating land for a dedicated capitol; construction of the current neoclassical Georgia State Capitol, featuring its iconic gold dome, commenced in 1886 and completed in 1889 at a cost of approximately $1 million.[4][23] In modern operations, the General Assembly convenes annually in the Atlanta State Capitol for a primary legislative session capped at 40 days, beginning on the second Monday in January as stipulated by the state constitution.[4][3] This structure, unchanged since the 1976 constitution, emphasizes efficiency in a bicameral body handling over 1,000 bills per session, with proceedings streamed online and accessible via the official legislative portal.[3] Special sessions may be called by the governor or legislative petition for urgent matters, as seen in responses to events like natural disasters or fiscal crises.[40] The Atlanta location facilitates proximity to executive agencies and lobbying interests, though it has drawn criticism for concentrating influence in urban metro areas distant from rural constituencies.[4]Organizational Structure

Senate Composition and Leadership

The Georgia State Senate consists of 56 members, each elected from a single-member district apportioned approximately equally by population following decennial redistricting based on the U.S. Census.[41][5] Senators serve two-year terms, with all 56 seats contested in even-numbered years and no constitutional term limits.[41][42] Eligibility requires candidates to be at least 25 years old, residents of Georgia for two years prior to election, and residents of their district for one year.[43] As of October 2025, Republicans hold a 33–23 majority.[44] The Lieutenant Governor serves ex officio as President of the Senate, presiding over floor proceedings, enforcing rules, assigning bills to committees, and casting deciding votes only on ties.[45] Burt Jones, a Republican elected in 2022, has occupied the position since January 2023.[46] The Senate elects a President pro tempore from its membership to assume presiding duties during the Lieutenant Governor's absence and to succeed to that office upon vacancy; the role also carries seniority privileges in committee assignments.[1] John Kennedy (R) held the position until May 2025, after which internal caucus selections positioned Larry Walker III (R) as nominee for continuation into the 2026 session.[47][48] Party caucuses select floor leaders to manage legislative strategy. The Majority Leader, elected by the dominant party, schedules debates, allocates speaking times, and advances the caucus agenda; Jason Anavitarte (R) assumed this role in June 2025 following prior leadership transitions.[49] The Minority Leader performs analogous functions for the opposition; Harold V. Jones II (D) was selected for the post entering the 2025 session.[50] These positions, while influential, operate within Senate rules emphasizing committee consensus and procedural votes.[1]House of Representatives Composition and Leadership

The Georgia House of Representatives comprises 180 members, each representing a single-member district apportioned based on population from the decennial census, with elections held every two years on even-numbered years coinciding with federal midterm or presidential cycles.[51] Members must be at least 21 years old, U.S. citizens, and residents of their district for one year preceding the election, serving without term limits.[51] Following the November 5, 2024, general election, Republicans maintained a majority with 100 seats, while Democrats hold 80 seats, reflecting a slim GOP edge sustained since 2005.[51] Leadership in the House is determined by party caucuses and formal votes at the session's opening, with the Speaker presiding over proceedings, assigning bills to committees, and influencing the legislative agenda as the chamber's highest officer.[51] The current Speaker is Jon Burns (Republican, District 159), elected to the role on January 9, 2023, succeeding David Ralston and focusing on budget priorities and rural economic issues during his tenure.[52] [53] The Majority Leader, Chuck Efstration (Republican, District 104), coordinates the GOP caucus strategy and floor operations, while the Minority Leader, Carolyn Hugley (Democrat, District 89), represents Democratic priorities such as education funding and voting access.[51] [50] These positions enable party leaders to shape debate rules, committee assignments, and resource allocation, with the Speaker holding veto power over certain procedural matters under House rules.[51]Committees and Administrative Operations

The Georgia General Assembly utilizes standing committees in both chambers to conduct in-depth analysis of referred legislation, including public hearings, amendments, and recommendations for floor action such as do-pass, substitute, or indefinite postponement. These committees are formed at the outset of each two-year General Assembly term under chamber-specific rules, with the Senate's Committee on Assignments appointing members, chairs, and subcommittees; senators generally serve on up to four standing committees, excluding certain oversight bodies like Assignments or Ethics.[54] The Senate maintains standing committees across policy domains including Appropriations (limited to 30 members), Judiciary (10 members), and Rules (14 members), while the House operates a parallel system with committees tailored to areas like Banks and Banking, Budget and Fiscal Affairs Oversight, and Transportation.[54] [55] Committee procedures mandate a quorum defined as a majority of assigned members, with no proxy voting permitted and recorded votes requiring at least one-third of those present; chairs' rulings on procedure may be appealed by majority vote, and reports must be written and signed.[54] Meetings are scheduled by the Secretary of the Senate (with Administrative Affairs approval) and posted publicly by Friday at 10:00 a.m., remaining open to the public except for specified executive sessions; bill authors receive opportunity to testify prior to votes.[54] Conference committees, convened ad hoc to resolve inter-chamber differences on identical bills, follow open-meeting requirements and may adopt their own conduct rules, with the Senate President appointing conferees.[54] Special and study committees address targeted issues, such as election procedures or gaming policy, beyond routine legislative work.[56] Administrative operations support committee and chamber functions through elected and appointed officers, including the constitutionally mandated Secretary of the Senate—who oversees journals, records, and bill filing deadlines (e.g., by 4:00 p.m. daily)—and the Clerk of the House, who performs analogous duties for parliamentary records and proceedings when both chambers convene.[16] [57] The Senate's Committee on Administrative Affairs manages staff hiring, supervision, compensation, supplies, and out-of-state travel approvals, while the nonpartisan Office of Legislative Counsel delivers bill drafting, code revision, and legal research services to both chambers.[54] [58] These elements ensure procedural integrity, with rules prohibiting staff interference in lobbying and requiring fiscal oversight for operational expenses.[54]Legislative Process

Sessions, Calendars, and Timelines

The Georgia General Assembly convenes in annual regular sessions beginning on the second Monday in January, as mandated by the state constitution.[59][3] These sessions are capped at 40 legislative days, where a legislative day constitutes a day of actual assembly excluding Sundays, holidays, and periods of recess unless otherwise resolved by the body.[60] In practice, sessions span approximately three to four months of calendar time due to intermittent recesses, with the 2025 session commencing on January 13 and adjourning sine die on April 4.[55][61] Bill prefiling commences on November 1 of the preceding year, allowing legislators to draft and submit proposed legislation prior to convening.[59] Key procedural timelines include committee assignments shortly after opening day, followed by hearings and amendments. Crossover Day, typically falling on or around the 30th legislative day (e.g., March 7 in 2025), requires bills to have passed at least one chamber to avoid expiration at sine die.[62][63] Following passage by both chambers, enrolled bills are transmitted to the Governor, who has six days (excluding Sundays) during session to sign or veto, after which unsigned bills become law; post-adjournment, the window extends to 40 days.[64][65] Each chamber publishes daily calendars outlining the agenda, including committee meetings, floor debates, and bills queued for third reading or final action.[66] These calendars prioritize general orders, local bills, and consent measures, with the House and Senate maintaining separate sequences to manage workload. Special sessions, convened by gubernatorial proclamation or legislative petition with a two-thirds quorum threshold, follow abbreviated timelines focused on enumerated purposes and lack the 40-day limit unless specified.[3][67]Bill Introduction, Debate, and Passage

Bills in the Georgia General Assembly may be introduced by any member in either chamber, except for appropriation and revenue-raising measures, which must originate in the House of Representatives as mandated by the state constitution.[68] Sponsors typically collaborate with the Office of Legislative Counsel to draft the bill, ensuring compliance with statutory formatting and researching relevant existing law.[69] Pre-filing of bills is permitted before the session convenes, with members-elect required to request fiscal notes by December 1 for bills intended for introduction in the upcoming session.[70] Upon filing with the clerk of the House or secretary of the Senate, the bill receives a number and is formally introduced on the next legislative day through its first reading, during which only the title is read aloud.[69] The presiding officer then refers it to an appropriate standing committee or subcommittee for review.[68] In committee, the bill undergoes public hearings where proponents, opponents, and experts may testify, followed by deliberations that can include amendments.[69] Committee chairs control the agenda, and a majority vote is required to report the bill favorably, with or without recommendations, to the full chamber; unfavorable reports or tabling effectively kill the bill unless reconsidered.[71] Reported bills proceed to a second reading, printed in the journal, and placed on the calendar for floor debate, where members propose amendments subject to germaneness rules and majority approval.[69] Debate is governed by chamber rules limiting time per speaker—typically up to 30 minutes initially in the Senate, adjustable by unanimous consent—and prioritizing the main question after amendments.[70] A constitutional majority (quorum present and majority voting aye) passes the bill on second reading, advancing it to third reading for engrossment and a final vote without further amendment, requiring the same majority for approval.[68] Upon passage in the originating chamber, the bill is transmitted to the second chamber, restarting the committee and floor processes identically, with potential amendments creating differences resolvable via a conference committee appointed by leadership from both houses.[69] Conference committees negotiate compromises, reporting a unified version for approval by majority vote in each chamber without further amendment.[71] Identical passage by both chambers enrolls the bill for gubernatorial consideration, with simple resolutions passing one chamber dying there unless concurred upon by the other.[68] This bicameral process ensures scrutiny but can extend timelines, as evidenced by the 2023-2024 session where over 1,200 bills were introduced but fewer than 200 enacted into law.Role of the Governor and Veto Override

The Governor of Georgia receives bills passed by both chambers of the General Assembly for approval, veto, or inaction, as outlined in Article III, Section V of the state constitution.[16] Upon transmittal, the Governor has 40 days during a legislative session—or 20 days after adjournment if the bill reaches the executive after sine die—to sign it into law, veto it, or allow it to become law without signature if no action is taken within the timeframe.[69][5] A veto requires the Governor to return the bill to the originating house with a written statement of objections, after which the General Assembly must reconsider it.[16] Override demands a two-thirds vote of the members present and voting in that house, followed by the same threshold in the second house; success enacts the bill into law notwithstanding the veto.[69][72] If the session has adjourned, veto overrides occur in the subsequent session, preserving legislative check on executive power.[73] For appropriation bills, the Governor holds line-item veto authority, enabling rejection of specific fiscal provisions while approving the remainder, subject to the same two-thirds override process.[60] This mechanism, rooted in Article V, Section II, Paragraph IV, allows targeted fiscal restraint without nullifying entire budgets.[16] Historically, veto overrides have been infrequent; for instance, during Republican trifectas since 2005, governors have sustained most vetoes due to partisan alignment, though isolated overrides, such as on education funding in 2010, demonstrate the threshold's viability when supermajorities falter.[72]Powers, Privileges, and Limitations

Core Legislative Powers

The legislative power of the state of Georgia is vested exclusively in the General Assembly, comprising the Senate and House of Representatives, as established by Article III, Section I of the state constitution.[16] This authority enables the body to enact statutes addressing public policy matters, including general laws of uniform statewide application—such as those governing education, criminal justice, taxation, and transportation—and local laws tailored to specific counties, municipalities, or districts, provided they do not conflict with general laws or constitutional prohibitions.[74] The General Assembly's lawmaking power is plenary within constitutional bounds, extending to regulation of commerce, public health, elections, and natural resources, but subject to limitations like the uniformity clause requiring equal application of general laws across similar classes.[16] A primary core power is fiscal authority, particularly through the appropriations process outlined in Article III, Section IX, where the General Assembly determines the state's operating budget by allocating revenues for executive agencies, infrastructure, and public services.[6] This includes levying taxes, authorizing bonds, and dedicating fees, with biennial budget acts typically passed during the legislative session; for instance, the fiscal year 2025 budget exceeded $35 billion in expenditures, reflecting priorities in education and transportation.[16] The body also serves as custodian of the treasury, overseeing state finances to ensure accountability in revenue collection and disbursement.[75] The General Assembly holds impeachment powers under Article III, Section VII, with the House of Representatives possessing sole authority to initiate charges against executive or judicial officers for malfeasance, and the Senate conducting trials, requiring a two-thirds vote for conviction and removal from office.[16] Additionally, it proposes constitutional amendments via majority approval in both chambers, followed by voter ratification in a statewide referendum, as seen in the 2018 amendments expanding opportunity school districts and ethics reforms.[6] These powers facilitate oversight of the executive branch and local governments, including investigations into agency operations and confirmation of certain gubernatorial appointees by the Senate, reinforcing checks on other branches while representing constituent interests in policy formation.[75]Member Privileges and Immunities

Members of the Georgia General Assembly possess privileges and immunities enshrined in Article III, Section VI, Paragraph VII of the Georgia Constitution of 1983, designed to protect legislative independence from executive or judicial interference during official duties.[16] These include freedom from arrest, except for treason, felony, or breach of the peace, applicable during sessions of the General Assembly, committee meetings, and travel to and from such proceedings.[5] This arrest immunity ensures members can attend legislative business without disruption from civil process or minor criminal matters, a provision rooted in common law traditions adapted to state governance.[76] The same constitutional paragraph extends immunity for speech and debate, stipulating that no member shall be liable or questioned elsewhere for words spoken in either house or any committee meeting thereof.[16] This clause shields legislators from civil suits, criminal prosecutions, or other accountability for legislative utterances and actions performed in their official capacity, fostering candid deliberation without fear of extraneous reprisal.[5] Georgia courts have interpreted this broadly to encompass core legislative functions, such as voting, introducing bills, and committee deliberations, but not extraneous activities like personal campaigns or constituent services outside formal proceedings.[76] Statutory law reinforces these constitutional safeguards. Under the Official Code of Georgia Annotated (O.C.G.A.), Title 28, members receive immunity from legal actions constituting harassment for conduct tied to legislative duties, extending protection to official acts beyond mere speech.[77] In 2023, both the Georgia House and Senate adopted internal rules broadening legislative privilege to include certain communications with third parties when linked to legislative activities, aiming to further insulate members from external pressures, though critics argued this reduced transparency.[78] These privileges do not confer absolute impunity; exceptions persist for non-legislative misconduct, and violations of ethical standards may trigger internal disciplinary measures by the respective houses.[76]Constitutional and Statutory Constraints

The Georgia Constitution vests legislative power in the General Assembly while imposing explicit limits to prevent abuse, ensure uniformity, and maintain fiscal discipline. Article III, Section IV, Paragraph I(a) restricts the regular annual session, which convenes on the second Monday in January, to no more than 40 legislative days in aggregate, excluding Sundays and legal holidays; extensions require a gubernatorial proclamation declaring an emergency or a two-thirds vote of each house followed by gubernatorial approval.[16] Special sessions, convened by the Governor or upon petition, are similarly limited to 40 days unless extended under the same conditions.[16] These caps aim to constrain prolonged deliberations and associated costs, reflecting a design for part-time citizen legislators rather than a full-time body.[16] Article III, Section VI delineates substantive prohibitions on legislative authority. Paragraph IV forbids the passage of local or special laws in 20 specified categories, including divorces, changing corporate names or charters, granting limited liability, legitimating bastards, authorizing lotteries (beyond the state lottery established separately), and altering venue in civil or criminal cases; such matters must instead be addressed through general laws of uniform statewide operation, with local exceptions requiring published notice, a local referendum, and two-thirds approval in each house.[16] Paragraph V(a) denies the power to grant incorporation or corporate powers to private persons or entities, mandating general laws for such grants.[16] Paragraph V(c) voids any contracts authorized by law that encourage monopolies, and Paragraph VI(a) prohibits donations, gratuities, or forgiveness of public debts due the state, except as constitutionally permitted for specific purposes like education or infrastructure.[16] Procedural constraints further bound legislative action. Article III, Section V, Paragraph III enforces a single-subject rule, prohibiting any bill from containing more than one subject matter or embracing matters not fairly expressed in its title, to prevent logrolling and ensure transparency.[16] Paragraph IV requires that bills amending or repealing existing laws or Code sections distinctly describe the altered provisions.[16] Section IV, Paragraph I(b) bars either house from adjourning for more than three consecutive days or convening outside the capitol without mutual consent, preserving bicameral coordination.[16] Appropriations are confined by Section IX, Paragraph IV(b), which limits expenditures to the unappropriated surplus plus estimated revenues, prohibiting deficits without voter-approved amendments.[16] Statutory constraints, derived from codes enacted under constitutional authority, primarily regulate internal operations and ethics rather than core powers, as Article III, Section I, Paragraph I declares that the General Assembly shall not abridge its constitutional powers nor enact laws construed to limit them.[16] For instance, the Official Code of Georgia Annotated (O.C.G.A.) Title 28 outlines ethics rules, including financial disclosure and lobbying restrictions under O.C.G.A. § 21-5-70 et seq., enforceable by the Georgia Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission, but these do not curtail substantive lawmaking. Procedural statutes, such as those governing open meetings (O.C.G.A. § 50-14-1 et seq.), apply to committees but yield to constitutional prerogatives. Violations of these can result in civil penalties or member sanctions, yet the legislature retains amendment authority, underscoring the primacy of constitutional over self-imposed limits.[16]Composition and Elections

Qualifications, Disqualifications, and Districts

The Georgia House of Representatives consists of 180 members, each elected from single-member districts apportioned by the General Assembly through general law following each decennial census to ensure substantially equal population representation.[79] Districts must be composed of contiguous territory and numbered consecutively, with reapportionment occurring after federal census data release to reflect population changes.[79] The Georgia State Senate comprises 56 members, similarly elected from single-member districts divided by general law, prioritizing compact and contiguous areas while adhering to equal population standards as required by the state constitution and federal law.[80] Senate districts often encompass multiple House districts, and redistricting follows the same census-driven process, with the General Assembly tasked with enacting maps that avoid diluting minority voting rights under applicable precedents.[80] Qualifications for House members include being at least 21 years old upon assuming office, a United States citizen, a Georgia citizen for at least two years preceding election, a legal resident of the district for at least one year prior to election, and a registered qualified voter.[81][5] Senate qualifications mirror these except for a minimum age of 25 years.[81][5] Disqualifications apply uniformly to both chambers and include conviction of a felony involving moral turpitude unless civil rights are restored and at least 10 years have passed without further such convictions; conviction for fraudulent election law violations or malfeasance in office absent rights restoration; holding another incompatible public office of profit or trust under federal, state, or foreign authority (with narrow exceptions like certain military service); unaccounted public funds; mental unsoundness or physical infirmity preventing duty performance; or failure to maintain district residency or voter registration.[81][5] Active-duty armed forces members are ineligible absent legislative exception, and legislators cannot accept new emolument-bearing offices created during their term without resigning their seat.[5] Ceasing to meet qualifications during a term results in office vacancy.[81]Election Procedures and Term Limits

Members of both the Georgia House of Representatives and the Georgia State Senate are elected to two-year terms in even-numbered years, with all 180 House seats and up to 56 Senate seats contested simultaneously.[5][59] This biennial election cycle aligns with the Georgia Constitution's provisions for short terms to ensure frequent accountability to voters.[5] Partisan primaries for legislative candidates are held on a date set by the Secretary of State, typically the third Tuesday in May of even-numbered years, as governed by the Georgia Election Code (O.C.G.A. Title 21).[82] Qualifying for primaries requires payment of a fee or submission of petitions, with major parties nominating candidates via these contests; if no primary candidate secures a majority, a runoff occurs about four weeks later between the top two vote-getters.[83] The general election follows on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November, employing a first-past-the-post system in single-member districts, where the candidate with the most votes wins regardless of majority threshold.[83][59] Vacancies arising mid-term—due to death, resignation, or expulsion—are filled via special elections called by the Governor under O.C.G.A. § 21-2-540, with writs issued no later than 10 days after the vacancy and the election held 30 to 60 days thereafter, subject to primary and runoff processes if necessary.[84] These procedures ensure minimal disruption while adhering to partisan selection norms. Georgia imposes no term limits on General Assembly members, permitting incumbents to seek and hold office indefinitely if reelected and meeting constitutional qualifications.[85] This absence of limits, shared by 34 other states, relies on electoral competition rather than arbitrary tenure caps to address concerns like entrenched power.[86] Proposals for limits, such as those advanced in recent sessions for federal offices, have not extended to state legislators.[87]Current and Historical Partisan Composition (as of 2025)

As of January 2025, Republicans hold a majority in both chambers of the Georgia General Assembly. The Senate comprises 33 Republicans and 23 Democrats out of 56 seats.[88] The House of Representatives consists of 100 Republicans and 80 Democrats out of 180 seats.[88] These figures reflect the composition following the November 5, 2024, elections, in which all legislative seats were contested; Republicans retained control but saw their House majority narrow from 102–78 to 100–80 due to Democratic gains in several districts.| Chamber | Republicans | Democrats | Total Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senate | 33 | 23 | 56 |

| House | 100 | 80 | 180 |