Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

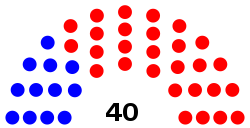

Florida Senate

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

|

|---|

The Florida Senate is the upper house of the Florida Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Florida, the Florida House of Representatives being the lower house. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution of Florida, adopted in 1968, defines the role of the Legislature and how it is to be constituted.[2] The Senate is composed of 40 members, each elected from a single-member district with a population of approximately 540,000 residents. The Senate Chamber is located in the State Capitol building.

The Republicans hold a supermajority in the chamber with 26 seats; Democrats are in the minority with 10 seats.[3] One seat is held by an independent, and three seats are vacant.

Terms

[edit]Article III of the Florida Constitution defines the terms for state legislators. The Constitution requires state senators from odd-numbered districts to be elected in the years that end in numbers that are multiples of four. Senators from even-numbered districts must be elected in even-numbered years, the numbers of which are not multiples of four.[4]

To reflect the results of the U.S. census and the redrawing of district boundaries, all seats are up for election in redistricting years, with some terms truncated as a result. Thus, senators in odd-numbered districts were elected to two-year terms in 2022 (following the 2020 census), and senators in even-numbered districts will be elected to two-year terms in 2032 (following the 2030 census).

Term limits

[edit]Candidates for re-election to the Florida Senate cannot appear on the ballot after serving for eight consecutive years. This was established by Amendment No. 9 (1992) affecting Article 6, Section 4 of the state Constitution.[4][5]

Qualifications

[edit]Florida legislators must be at least twenty-one years old, an elector and resident of their district, and must have resided in Florida for at least two years prior to election.[2]

Legislative session

[edit]

Each year during which the Legislature meets constitutes a new legislative session.

Regular legislative session

[edit]

The Florida Legislature meets in a 60-day regular legislative session each year. Regular sessions in odd-numbered years must begin on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in March. Under the State Constitution, the Legislature can begin even-numbered year regular sessions at a time of its choosing.[4]

Special session

[edit]Special legislative sessions may be called by the governor, by a joint proclamation of the Senate president and House speaker, or by a three-fifths vote of all legislators. During a special session, the Legislature may only address legislative business that is within the purpose or purposes stated in the proclamation calling the session.[4]

Powers and process

[edit]The Florida Statutes are the codified statutory laws of the state.[6]

Leadership

[edit]The Senate is headed by the Senate President, who controls the agenda along with the Speaker of the House and Governor.[citation needed]

- President: Ben Albritton (R)

- President Pro Tempore: Jason Brodeur (R)

- Majority Leader: Jim Boyd (R)

- Minority Leader: Lori Berman (D)

Composition

[edit]| Affiliation | Party (Shading indicates majority caucus)

|

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Democratic | Independent | Vacant | ||

| End of 2020–22 legislature | 23 | 16 | 0 | 39 | 1 |

| Start of previous (2022–24) legislature | 28 | 12 | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| End of previous legislature | |||||

| Start of current (2024–26) legislature | 28 | 12 | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| February 13, 2025[a] | 11 | 39 | 1 | ||

| March 31, 2025[b] | 27 | 38 | 2 | ||

| April 24, 2025[c] | 10 | 1 | |||

| June 10, 2025[d] | 28 | 39 | 1 | ||

| July 21, 2025[e] | 27 | 38 | 2 | ||

| August 12, 2025[f] | 26 | 37 | 3 | ||

| September 2, 2025[g] | 11 | 38 | 2 | ||

| Latest voting share | 70.3% | 27% | 2.7% | ||

Members, 2024–2026

[edit]*Elected in a special election.

District map

[edit]

Past composition of the Senate

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Democrat Geraldine Thompson (District 15) died.[7]

- ^ Republican Randy Fine (District 19) resigned effective this date to run for Congress.[8]

- ^ Jason Pizzo (District 37) changed party affiliation from Democrat to no party affiliation.[9]

- ^ Republican Debbie Mayfield elected to replace Randy Fine (District 19).[10]

- ^ Republican Blaise Ingoglia (District 11) resigned after being appointed state Chief Financial Officer.[11]

- ^ Republican Jay Collins (District 14) resigned after being appointed Lieutenant Governor.[12]

- ^ Democrat LaVon Bracy Davis elected to replace Geraldine Thompson (District 15).[13]

References

[edit]- ^ "The 2017 Florida Statutes F.S. 11.13 Compensation of members". Florida Legislature.

- ^ a b "Florida Statutes". Florida Legislature. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ "Senators". Florida Senate.

- ^ a b c d "The Florida Constitution". Florida Legislature.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Vote Yes On Amendment No. 9 To Begin Limiting Political Terms". Sun-Sentinel. October 27, 1992. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "Statutes & Constitution: Online Sunshine". Florida Legislature. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ Petro, Allison (February 13, 2025). "Florida State Senator Geraldine Thompson dies at 76, family says". WESH. Retrieved February 13, 2025.

- ^ Berman, David (November 27, 2024). "Fine to run for Congress in Daytona Beach area; Mayfield seeks return to Florida Senate". Florida Today. Retrieved April 1, 2025.

- ^ Ellenbogen, Romy (April 24, 2024). "Florida Senate Democratic leader drops party, switches to no-party affiliation". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved April 24, 2025.

- ^ Costeines, Michael (June 11, 2025). "Florida Republicans Earn Clean Sweep in Special Elections". The Floridian. Retrieved June 11, 2025.

- ^ Swisher, Skyler (July 16, 2025). "DeSantis names Sen. Blaise Ingoglia Florida's next CFO". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved July 16, 2025.

- ^ Rohrer, Gray; Bridges, C.A. (August 12, 2025). "Gov. Ron DeSantis taps Jay Collins to be lieutenant governor of Florida". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ Ogles, Jacob (September 2, 2025). "LaVon Bracy Davis will succeed Geraldine Thompson in SD 15 following Special Election win". Florida Politics. Retrieved September 3, 2025.

- ^ And previous terms of service, if any.

External links

[edit]Florida Senate

View on GrokipediaHistory

Establishment and Constitutional Foundations

The Florida Senate traces its origins to the territorial period, when Congress authorized the reorganization of the legislative structure on July 7, 1838, establishing a bicameral system comprising a Senate as the upper house and a House of Representatives, replacing the prior unicameral body that had operated since 1822.[9] This change aligned with preparations for statehood, as delegates convened a constitutional convention in St. Joseph from December 1838 to January 1839, drafting Florida's first constitution, which outlined the Senate's composition, powers, and procedures modeled on the deliberative upper chamber of the U.S. Congress to ensure more measured legislative review.[10] The document emphasized representation by senatorial districts, with senators elected for terms intended to promote stability amid the territory's agrarian economy dominated by cotton plantations and slave labor.[11] Florida achieved statehood on March 3, 1845, as the 27th state, with the new constitution taking effect and the first state Senate convening that year, initially consisting of 19 senators apportioned across districts reflecting the population centers in the northern and panhandle regions.[12][13] The bicameral framework, directly inspired by the federal model, positioned the Senate to check hasty House actions, fostering deliberation on issues like land distribution, internal improvements, and protections for slavery, which the constitution explicitly accommodated by prohibiting state interference with the institution.[14] Pre-Civil War sessions prioritized agrarian interests, enacting laws supportive of plantation agriculture and slave-based production, which formed the backbone of the state's export economy.[15] The Senate's structure underwent significant alteration during Reconstruction following the Civil War. After Florida's secession and the Confederate constitution of 1861, federal military occupation and congressional mandates under Radical Republican influence led to a new constitutional convention in 1868, which expanded civil rights, imposed loyalty oaths, and restructured the legislature to include broader enfranchisement, including African American voters, resulting in a Senate more aligned with national Republican priorities for remaking Southern institutions.[16][17] This 1868 framework marked a departure from antebellum designs, emphasizing federal oversight to prevent restoration of pre-war power dynamics.[18]Evolution Through Reconstructions and Reforms

The Constitution of 1868, adopted during Reconstruction to facilitate Florida's readmission to the Union, restructured the Senate into 24 single-member districts apportioned among counties, expanding from the prior territorial and early state frameworks that had as few as 17 members.[19] This increase reflected population redistribution post-Civil War, while provisions requiring Senate confirmation of gubernatorial appointments for cabinet positions and militia officers limited executive dominance, a response to centralized power under federal military oversight.[19] Impeachment authority vested solely in the Senate further checked potential gubernatorial overreach.[19] The 1885 Constitution, drafted after Democrats regained control ending Reconstruction-era Republican governance, capped the Senate at no more than 32 members, maintaining a county-based apportionment that guaranteed minimal representation to less populous areas.[20] This structure, prioritizing county lines over strict population equality, overrepresented rural, white-majority counties—often at ratios exceeding 10:1 in vote dilution—entrenched one-party Democratic dominance and aligned with Jim Crow policies that segregated public facilities and suppressed black voter participation through poll taxes and literacy tests.[20] [21] Such biases persisted due to infrequent reapportionment, shielding agrarian interests from urban demographic shifts until federal courts, invoking equal protection, mandated reforms.[22] The 1968 Constitution, revised amid national litigation on legislative malapportionment, required decennial reapportionment based on census data to approximate equal population districts, directly addressing rulings like Baker v. Carr (1962), which deemed such disparities justiciable under the Equal Protection Clause.[23] [5] Permitting 30 to 40 senators, it accommodated Florida's postwar population boom; by 1972, the legislature enacted 40 single-member districts to align with urban growth in areas like Miami and Tampa, reducing rural overrepresentation from prior decades.[6] This shift causally linked to suburbanization and migration, compelling representation proportional to actual voter bases rather than geographic units.[24] In 1992, voters approved Amendment 9, amending the constitution to impose consecutive eight-year term limits on senators, prohibiting ballot access after two full terms in the same chamber.) Motivated by public frustration with long-tenured incumbents amid rising scandals and perceived legislative inertia, the measure aimed to enhance turnover and responsiveness to evolving demographics, though it accelerated leadership instability without altering underlying partisan dynamics.[25]20th and 21st Century Shifts in Partisan Control

Throughout the 20th century, the Florida Senate remained under Democratic control, reflecting the state's one-party dominance following Reconstruction, with Democrats holding supermajorities from the 1880s through the 1990s.[26] This persisted despite a national conservative wave in the 1966 midterm elections, during which Republicans gained seats in the state legislature amid gains in governorships and congressional races, though Democrats retained overall Senate majority.[27][26] Republicans achieved a historic breakthrough in the 1996 midterm elections, securing a narrow majority in the Senate for the first time since Reconstruction, with 23 seats to Democrats' 17.[28][29] This marked the start of sustained Republican gains, expanding to a supermajority by the 2020 elections and reaching 28-12 following the 2024 elections for the 2024-2026 term.[4][4] These shifts correlate with demographic changes, including rapid population growth from domestic migration to the Sun Belt, which added over 1 million residents in recent decades and favored Republican-leaning voters seeking lower taxes and business-friendly policies.[30][31] Shifts among Hispanic voters, particularly in South Florida, further bolstered Republican margins, with turnout and preference data showing increased support for GOP candidates in urban and suburban districts.[31][32] Under Republican legislative control since 1997, Florida's real GDP growth has doubled the national rate over the past five years, from 2020 to 2024, amid private-sector job expansion outpacing U.S. averages.[33][26]Structure and Organization

Terms, Elections, and Term Limits

Members of the Florida Senate serve staggered four-year terms, with elections conducted biennially in even-numbered years for 20 of the 40 seats.[34][35] Under Article III, Section 15(a) of the state constitution, senators from odd-numbered districts are elected in years divisible by four (such as 2024), while those from even-numbered districts are elected in other even years, with adjustments following reapportionment to maintain the balance. This arrangement aligns Senate elections with federal midterm and presidential cycles, leveraging elevated voter participation rates associated with national contests.[36] Constitutional term limits, ratified by voters in 1992 via Amendment 9, restrict senators to no more than two consecutive terms (eight years total) in the chamber.)[37] Article VI, Section 4(b) bars ballot access for Senate re-election if a senator will have completed eight consecutive years by term's end, inclusive of partial terms from special elections or apportionment shifts, but permits non-consecutive returns after a one-term hiatus and imposes no lifetime cap.[35] The combination of staggering and limits fosters partial continuity—averting full biennial turnover—while enforcing periodic renewal to counter incumbency advantages, though it elevates incentives for senators to eye higher office mid-tenure. Post-1992 implementation has yielded markedly higher turnover, with freshman cohorts comprising 40-50% of senators in affected cycles versus under 20% pre-limits, correlating with shorter average tenures and a rise in legislators lacking prior public service.[38][39] This influx of relative novices has amplified dependence on executive-branch and lobbyist input for legislative drafting and expertise, potentially accelerating adaptation to emergent policy demands but diluting chamber-specific knowledge accumulation.[40] Empirical assessments show sustained or elevated legislative output volume without evident corruption abatement, underscoring limits' role in prioritizing electoral refresh over entrenched expertise.[41]Qualifications for Membership

To serve in the Florida Senate, candidates must meet the criteria established in Article III, Section 15 of the Florida Constitution: attainment of at least 21 years of age, status as a qualified elector, residency in the district from which elected, and residence in the state for one year preceding the election.[42] Qualified elector status, as defined under Article VI, Section 2, requires United States citizenship, a minimum age of 18 years, and permanent residency in Florida.[43] Felony convictions do not permanently bar eligibility provided voting rights are restored upon completion of all sentence terms, including prison, probation, and parole; this restoration, enacted via voter-approved Amendment 4 in November 2018, applies to most felons but excludes those convicted of murder or felony sexual offenses from automatic reinstatement without further process.[44]) Subsequent legislative requirements for payment of fines and fees to regain rights were partially invalidated by court rulings, affirming the amendment's intent to prioritize sentence completion over financial obligations.[45] These eligibility standards mirror those for the Florida House of Representatives, with no additional age, residency, or other thresholds imposed on senators.[46] The uniformity underscores the constitution's intent for accessible legislative service, though the Senate's staggered four-year terms—versus the House's biennial elections—facilitate longer tenures that can enhance policy continuity and institutional knowledge among senators.[42] Disqualifications beyond standard criteria, such as through ethics investigations leading to removal, remain exceptional and require judicial or legislative action.[47]Districts, Apportionment, and Redistricting

The Florida Senate comprises 40 single-member districts, each designed to encompass substantially equal populations in compliance with the one-person, one-vote principle established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Reynolds v. Sims (1964). Prior to reapportionment in the 1960s, districts were malapportioned, overweighting rural areas with minimal population growth relative to urban centers, a practice invalidated by federal courts mandating equal population deviation no greater than 10% across districts.[48] Following the 2020 Census, which recorded Florida's population at 21,538,187, each Senate district targets approximately 538,455 residents, with actual deviations minimized through legislative adjustments to reflect decennial shifts in population centers.[49] Redistricting for Senate districts occurs decennially, with the state legislature responsible for drawing boundaries via joint resolution during the regular session two years after the Census, without gubernatorial veto power over state legislative plans.[50] The process adheres to criteria in Article III, Section 20 of the Florida Constitution, amended by voter-approved Fair Districts Amendments 5 and 6 on November 2, 2010—passed with 62.3% and 63.6% support, respectively—which prohibit districts drawn with intent to favor or disfavor a political party, incumbent, or group, while requiring compactness, contiguity, preservation of communities of interest, and avoidance of minority vote dilution.[51] These amendments ban mid-decade redistricting absent court order, emphasizing neutral criteria over partisan outcomes, though courts evaluate compliance holistically rather than via strict numerical thresholds.[52] After the 2020 Census, the legislature enacted the current Senate map through Senate Joint Resolution 100, approved February 3, 2022, which rebalanced districts to account for population growth in suburbs and the Sun Belt interior while maintaining urban concentrations. The Florida Supreme Court reviewed and upheld the plan on March 3, 2022, affirming it met Fair Districts standards without evidence of prohibited intent, as boundaries followed natural geographic and demographic contours rather than contrived shapes.[53] No successful challenges alleged racial gerrymandering under the Voting Rights Act Section 2, with the map preserving opportunity districts where Black voters comprise effective majorities or coalitions capable of electing preferred candidates, evaluated under totality-of-circumstances tests including racial polarization and district performance history. The resulting configuration yields Republican majorities reflective of statewide vote shares—where Democrats cluster in coastal and metropolitan enclaves, enabling efficient Republican distribution across rural and exurban areas—without diluting minority influence beyond what geography necessitates.[54]Legislative Operations

Sessions and Meeting Protocols

The Florida Senate convenes in regular sessions annually as mandated by Article III, Section 3 of the Florida Constitution. In odd-numbered years, sessions begin on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in March and last no more than 60 consecutive days.[5] In even-numbered years, they start on the second Tuesday after the first Monday in March and extend up to 60 calendar days, with possible extension by joint agreement of both legislative houses for up to 30 additional calendar days.[5] These sessions focus on enacting the state budget in even years and addressing policy matters in odd years, promoting legislative efficiency while limiting duration to prevent prolonged disruptions to governance.[55] An organizational session occurs on the 14th day following each general election in November, lasting no more than two weeks for preparatory purposes.[5] This session enables the Senate to organize its operations ahead of the regular session, ensuring readiness without delving into substantive legislation.[56] Special sessions are convened either by proclamation of the governor or by joint proclamation of the Senate President and House Speaker, requiring signatures from at least 20% of legislative members.[55] Such sessions are capped at 20 consecutive days and restricted to the purposes outlined in the call, serving as a mechanism for addressing urgent issues while curbing executive overreach through defined scopes.[57] Veto overrides during these or regular sessions demand a two-thirds vote of each house's membership, providing a check on gubernatorial power.[5] Senate protocols emphasize transparency and order, with a quorum of 21 members required for proceedings, constituting a majority of the 40 senators.[58] Daily sessions commence with a roll call conducted by the Secretary to ascertain attendance and quorum.[58] Article III, Section 4 mandates that all sessions be open to the public, aligning with Florida's Sunshine Law to foster accountability.[5] While primarily in-person, temporary hybrid remote participation was authorized during the COVID-19 pandemic for continuity, though post-emergency operations have reverted to physical attendance with limited virtual committee options.[59]Powers, Procedures, and Bill Enactment

The Florida Senate holds exclusive authority to confirm gubernatorial appointments to various executive branch positions, state agency heads, and certain judicial roles, a process requiring a majority vote following review by relevant committees.[60] [61] This confirmation power ensures legislative oversight of key administrative roles, with appointees submitting detailed questionnaires and appearing before Senate committees for examination.[62] Additionally, the Senate conducts trials for officials impeached by the House of Representatives, serving as the court of impeachment with a two-thirds vote required for conviction and removal from office.[5] In conjunction with the House, the Senate approves interstate compacts, which facilitate cooperation on issues like environmental regulation and professional licensure, often enacted through joint legislative resolution.[63] [64] The enactment of bills in the Senate adheres to bicameral procedures outlined in the state constitution and chamber rules, requiring consensus between both legislative houses for passage. Bills may be introduced by senators or, for certain revenue measures, originate in the House before Senate consideration; general appropriations bills specifically begin in the House but undergo Senate amendments prior to final form.[36] [65] Each bill receives three readings: the first by title upon introduction, the second allowing for debate and amendments after committee review, and the third for final passage debate and vote, typically requiring a simple majority unless a higher threshold is specified.[36] [66] Amendments adopted in one chamber necessitate concurrence from the other, potentially leading to conference committees to reconcile differences and produce a unified version for approval.[65] Upon bicameral passage, bills are presented to the governor for signature, pocket veto, or line-item veto in the case of appropriations acts. Legislative override of a veto demands a two-thirds supermajority in both the Senate and House, a threshold met infrequently due to partisan alignment and procedural hurdles.[36] Historical data indicate that approximately 95% of gubernatorial vetoes have been sustained since statehood, underscoring the legislature's deference to executive judgment, though override rates rose modestly during divided government periods before Republican unification of the governorship and legislature in the late 1990s.[67] This pattern reflects empirical trends where unified government correlates with fewer challenges to vetoes, as evidenced by rare successful overrides, such as the 2025 restoration of vetoed legislative support funding.[68]Leadership Roles and Committee System

The Florida Senate's leadership structure centers on the President, elected by a majority vote of senators during the organizational session held 14 days after general elections. The President, invariably from the majority party, presides over floor sessions, appoints committee chairs and members, and oversees administrative operations, wielding significant influence over the legislative agenda through control of bill referrals and debate scheduling.[69][70] The President pro tempore, similarly elected by the body, assumes presiding duties in the President's absence and often handles ceremonial functions, providing continuity amid absences or vacancies.[58] Partisan caucuses play a pivotal role in leadership selection and operations, with the majority leader—elected internally by the dominant party's members—coordinating strategy, whip operations, and committee assignments for Republican senators, while the minority leader performs analogous functions for Democrats.[71] These leaders facilitate party-line voting and negotiate priorities, particularly under the current Republican supermajority of 28 seats to 12 Democratic seats in the 2024–2026 term, which enables expedited consideration of majority-backed bills with success rates exceeding 80% for sponsored legislation in recent sessions.[72] Constitutional term limits, restricting senators to two consecutive four-year terms, contribute to measured leadership turnover, as incoming cohorts from the majority caucus maintain ideological alignment and agenda focus despite periodic changes.[5] The committee system forms the core of legislative deliberation, comprising 27 standing committees that handle bill review, amendments, and policy expertise in areas such as Appropriations (overseeing budget allocations), Rules (governing procedural matters), and specialized panels like Health Policy and Criminal Justice.[73] Committees typically range from 10 to 20 members, with membership and chairmanships allocated by the President in consultation with caucus leaders, ensuring majority party dominance in key fiscal and regulatory bodies.[73] Beyond regular sessions, interim committees and select study groups—convened by leadership—conduct off-session research and hearings on emerging issues, such as economic forecasting or regulatory reforms, informing subsequent legislative priorities without requiring full floor action.[74] This structure enhances efficiency in a supermajority environment, where committee approvals predictably advance to floor votes, minimizing bottlenecks observed in balanced chambers.[75]Composition and Representation

Current Membership (2024–2026 Term)

The Florida Senate for the 2024–2026 term comprises 40 single-member districts, with 39 seats occupied as of October 2025 due to a vacancy in District 14 following the gubernatorial appointment of former Republican Senator Jay Collins as Lieutenant Governor.[76][77] This results in 27 Republicans and 12 Democrats holding seats, preserving the Republican supermajority.[4] A special election for District 14, covering parts of Hillsborough County, was called on October 24, 2025, with qualifying in November 2025 and the general election in January 2026.[78][79] Senate President Ben Albritton, a Republican from District 27 (encompassing Charlotte, DeSoto, Hardee, and portions of Lee and Polk counties), presides over the chamber, elected by fellow senators at the start of the term.[80][3] Districts are apportioned based on the 2020 census, balancing population across diverse geographies: urban centers like Miami (Districts 35–40, mostly Democratic-held with higher minority populations) contrast with rural Panhandle areas (Districts 1–4, solidly Republican) and suburban swings in Central Florida.[4]| District Range | Geographic Focus | Predominant Party (Occupied Seats) |

|---|---|---|

| 1–4 | Rural Panhandle (e.g., Escambia, Bay counties) | Republican (4/4) |

| 5–10 | North Florida (e.g., Jacksonville suburbs, Gainesville) | Republican (5/6) |

| 11–20 | Central/North Central (e.g., Tampa, Orlando edges) | Republican (8/9, 1 vacant) |

| 21–30 | South Central (e.g., Sarasota, Polk County) | Republican (9/10) |

| 31–40 | South Florida (e.g., Miami-Dade, Broward) | Mixed: Republican (1/10), Democratic (9/10) |

Historical Partisan Composition

The Florida Senate was controlled by Democrats for the majority of its history through the mid-20th century, consistent with the Democratic dominance in Southern state legislatures during the Solid South era.[26] In 1990, Democrats held 23 seats to Republicans' 17 in the 40-member chamber.[82] This Democratic trifecta, including control of the governorship and House, facilitated periods of expanded state regulation and spending growth, particularly in areas like environmental and social programs amid post-World War II population booms.[26] A pivotal shift occurred in the 1990s, driven by voter dissatisfaction with rising property taxes and regulatory burdens amid rapid urbanization and real estate appreciation.[83] The 1992 elections resulted in a 20-20 tie, leading to a power-sharing agreement.[4] Republicans gained a slim majority after the 1994 elections with 21 seats to Democrats' 19, marking the first GOP Senate control since Reconstruction.[4] This flipped to 23 Republicans in 1996, solidifying control as the party capitalized on national GOP waves and local tax revolt sentiments, including grassroots efforts to cap assessments.[4][84] Republicans have maintained majority control since 1995, with seat shares expanding amid demographic changes.[4] The partisan composition evolved as follows after key elections:| Election Year | Republicans | Democrats |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 21 | 19 |

| 1996 | 23 | 17 |

| 1998 | 25 | 15 |

| 2000 | 25 | 15 |

| 2002 | 26 | 14 |

| 2010 | 28 | 12 |

| 2018 | 23 | 17 |

| 2020 | 24 | 16 |

| 2022 | 28 | 12 |

| 2024 | 28 | 12 |