Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

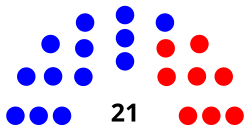

Nevada Senate

View on WikipediaThe Nevada Senate is the upper house of the Nevada Legislature, the state legislature of U.S. state of Nevada, the lower house being the Nevada Assembly. It currently (2012–2021) consists of 21 members from single-member districts.[1] In the previous redistricting (2002–2011) there were 19 districts, two of which were multimember. Since 2012, there have been 21 districts, each formed by combining two neighboring state assembly districts. Each state senator represented approximately 128,598 as of the 2010 United States census. Article Four of the Constitution of Nevada sets that state senators serve staggered four-year terms.[2]

Key Information

In addition, the size of the Senate is set to be no less than one-third and no greater than one-half of the size of the Assembly.[3] Term limits, limiting senators to three 4-year terms (12 years), took effect in 2010. Because of the change in Constitution, seven senators were termed out in 2010, four were termed out in 2012, and one was termed out in 2014. The Senate met at the Nevada State Capitol in Carson City until 1971, when a separate Legislative Building was constructed south of the Capitol. The Legislative Building was expanded in 1997 to its current appearance to accommodate the growing Legislature.

History

[edit]Boom and Bust era (1861–1918)

[edit]The first session of the Nevada Territorial Legislature was held in 1861. The Council was the precursor to the current Senate and the opposite chamber was called a House of Representatives which was later changed to be called the Assembly. There were nine members of the original Council in 1861 elected from districts as counties were not yet established.[4] Counties were established in the First Session of the Territorial Legislature and the size of the Council was increased to thirteen. From the first session of the Nevada Legislature once statehood was granted the size of the Senate ranged from eighteen members, in 1864, to a low of fifteen members from 1891 through 1899, and a high of twenty-five members from 1875 through 1879.[5]

Little Federalism era (1919–1966)

[edit]In 1919 the Senate started a practice called "Little Federalism," where each county received one member of the Nevada Senate regardless of population of said county. This set the Senate membership at seventeen which lasted until 1965–1967. The Supreme Court of the United States issued the opinion in Baker v. Carr in 1962 which found that the redistricting of state legislative districts are not political questions, and thus are justiciable by the federal courts. In 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court heard Reynolds v. Sims and struck down state senate inequality, basing their decision on the principle of "one person, one vote." With those two cases being decided on a national level, Nevada Assemblywoman Flora Dungan and Las Vegas resident Clare W. Woodbury, M.D. filed suit in 1965 with the United States District Court for the District of Nevada arguing that Nevada's Senate districts violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States and lacked of fair representation and proportional districts. At the time, less than 8 percent of the population of the State of Nevada controlled more than 50 percent of the Senate seats. The District Court found that both the Senate and the Assembly apportionment laws were "invidiously discriminatory, being based upon no constitutionally valid policy.[6]" It was ordered that Governor Grant Sawyer call a Special Session to submit a constitutionally valid reapportionment plan.[7] The 11th Special Session lasted from October 25, 1965 through November 13, 1965 and a plan was adopted to increase the size of the Senate from 17 to 20.

Modern era (1967–present)

[edit]The first election after the judicial intervention and newly adopted apportionment law was 1966 and its subsequent legislature consisted of 40 members from the Assembly and 20 members from the Senate. Nine incumbent senators from 1965 were not present in the legislature in 1967.[8] In the 1981 Legislative Session the size of the Senate was increased to twenty-one because of the population growth in Clark County. Following the 2008 election, Democrats took control of the Nevada Senate for the first time since 1991. In January 2011, Senator William Raggio resigned after 38 years of service.[9] On January 18, 2011, the Washoe County Commission selected former member of the Nevada Assembly and former United States Attorney Gregory Brower to fill the vacancy and remainder of the term of Senator William Raggio. After the 76th Session and the decennial redistricting the boundary changes and demographic profiles of the districts prompted a resignation of Senator Sheila Leslie, in February 2012, and she announced her intention to run against Sen. Greg Brower in 2012.[10] Later in February 2012, citing personal reasons, Senator Elizabeth Halseth resigned her suburban/rural Clark County seat.[11]

Legislative sessions

[edit]| Legislative Session | Party (Shading indicates majority caucus)

|

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | |||

| 62nd Legislative Session, 1967 | 11 | 9 | 20 | |

| 63rd Legislative Session, 1969 | 11 | 9 | 20 | |

| 56th Legislative Session, 1971 | 13 | 7 | 20 | |

| 57th Legislative Session, 1973 | 14 | 6 | 20 | |

| 58th Legislative Session, 1975 | 17 | 3 | 20 | |

| 59th Legislative Session, 1977 | 17 | 3 | 20 | |

| 60th Legislative Session, 1979 | 15 | 5 | 20 | |

| 61st Legislative Session, 1981 | 15 | 5 | 20 | |

| 62nd Legislative Session, 1983 | 17 | 4 | 21 | |

| 63rd Legislative Session, 1985 | 13 | 8 | 21 | |

| 64th Legislative Session, 1987 | 9 | 12 | 21 | |

| 65th Legislative Session, 1989 | 8 | 13 | 21 | |

| 66th Legislative Session, 1991 | 11 | 10 | 21 | |

| 67th Legislative Session, 1993 | 10 | 11 | 21 | |

| 68th Legislative Session, 1995 | 8 | 13 | 21 | |

| 69th Legislative Session, 1997 | 9 | 12 | 21 | |

| 70th Legislative Session, 1999 | 9 | 12 | 21 | |

| 71st Legislative Session, 2001 | 9 | 12 | 21 | |

| 72nd Legislative Session, 2003 | 8 | 13 | 21 | |

| 73rd Legislative Session, 2005 | 10 | 11 | 21 | |

| 74th Legislative Session, 2007 | 10 | 11 | 21 | |

| 75th Legislative Session, 2009 | 12 | 9 | 21 | |

| 76th Legislative Session, 2011 | 11 | 10 | 21 | |

| 77th Legislative Session, 2013 | 11 | 10 | 21 | |

| 78th Legislative Session, 2015 | 10 | 11 | 21 | |

| 79th Legislative Session, 2017 | 11† | 8 | 21 | |

| 80th Legislative Session, 2019 | 13 | 8 | 21 | |

| 81st Legislative Session, 2021 | 12 | 9 | 21 | |

| 82nd Legislative Session, 2023 | 13 | 8 | 21 | |

| 83rd Legislative Session, 2025 | 13 | 8 | 21 | |

| Latest voting share | 61.9% | 38.1% | ||

Current session

[edit]

| ↓ | ||

| 13 | 8 | |

| Democratic | Republican | |

| Affiliation | Party (Shading indicates majority caucus)

|

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Ind | Republican | Vacant | ||

| Begin 78th, February 2014 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 0 |

| End 78th, November 2016 | |||||

| Begin 79th, February 2017 | 11 | 0 | 10 | 21 | 0 |

| End 79th, November 2018 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 19 | 2 |

| November 7, 2018[12] | 13 | 0 | 8 | 21 | 0 |

| December 4, 2018[13] | |||||

| March 5, 2019[14] | 12 | 20 | 1 | ||

| March 15, 2019[15] | 13 | 21 | 0 | ||

| Begin 82nd, February 2023 | 13 | 0 | 8 | 21 | 0 |

| October 26, 2023[16] | 7 | 20 | 1 | ||

| Latest voting share | 65% | 35% | |||

Composition and leadership of the 82nd Legislative session

[edit]Presiding over the Senate

[edit]The president of the Senate is the body's highest officer, although they only vote in the case of a tie, and only on procedural matters. Per Article 5, Section 17 of the Nevada Constitution, the lieutenant governor of Nevada serves as Senate president. In their absence, the president pro tempore presides and has the power to make commission and committee appointments. The president pro tempore is elected to the position by the majority party. The other partisan Senate leadership positions, such as the leader of the Senate and minority leader, are elected by their respective party caucuses to head their parties in the chamber. The current president of the Senate is Nevada Lieutenant Governor Stavros Anthony of the Republican Party.

Non-member officers

[edit]On the first day of a regular session, the Senate elects the non-member, nonpartisan administrative officers including the secretary of the Senate and the Senate sergeant at arms. The secretary of the Senate serves as the parliamentarian and chief administrative officer of the Senate and the sergeant at arms is chief of decorum and order for the Senate floor, galleries, and committee rooms. Claire J. Clift was originally appointed by then Republican Senate majority leader William Raggio. The Democratic Party took the majority in 2008 and she was retained until 2010.[17] In August 2010, then Senate majority leader Steven Horsford appointed David Byerman as the 41st secretary of the Senate.[18] The day after the 2014 general election, David Byerman was removed from his position and the previous secretary, Claire J. Clift, was re-appointed.[19] Retired chief of police Robert G. Milby was chosen as the Senate sergeant at arms for the 78th Legislative by the Republican majority leader. Both of the elected non-member officers serve at the pleasure of the Senate, thus they have a two-year term until the succeeding session. The Senate also approves by resolution the remainder of the nonpartisan Senate Session staff to work until the remainder of the 120 calendar day session.

83rd session leadership

[edit]Leadership

[edit]| Position | Name | Party | District |

|---|---|---|---|

| President/Lt. Governor | Stavros Anthony | Republican | N/A |

| President pro tempore | Marilyn Dondero Loop | Democratic | District 8 |

Majority leadership

[edit]| Position | Name | Party | District |

|---|---|---|---|

| Majority Leader | Nicole Cannizzaro | Democratic | District 6 |

| Assistant Majority Leader | Roberta Lange | Democratic | District 7 |

| Chief Majority Whip | Melanie Scheible | Democratic | District 9 |

| Deputy Majority Whip | Fabian Doñate | Democratic | District 10 |

| Deputy Majority Whip | Skip Daly | Democratic | District 13 |

Minority leadership

[edit]| Position | Name | Party | District |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minority Leader | Robin Titus | Republican | District 17 |

| Assistant Minority Leader | Jeff Stone | Republican | District 20 |

| Minority Whip | Lisa Krasner | Republican | District 16 |

Members of the 83rd Senate

[edit]Districts of the Nevada Assembly are nested inside the Senate districts, two per Senate district. The final Legislative redistricting plans as created by the Special Masters in 2011 and approved by District Court Judge James Todd Russell represent the first time since statehood Nevada's Assembly districts are wholly nested inside of a Senate district. Each Assembly district represents 1/42nd of Nevada's population and there are two Assembly districts per Senate district which represents 1/21st of Nevada's population.[20]

| District | Assembly Districts |

Name | Party | Residence | Assumed office | Next election |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 17 | Michelee Crawford | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2024 | 2028 |

| 2 | 11, 28 | Edgar Flores | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2022 | 2026 |

| 3 | 3, 10 | Rochelle Nguyen | Democratic | Las Vegas | 20221 | 2028 |

| 4 | 6, 7 | Dina Neal | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2020 | 2028 |

| 5 | 22, 29 | Carrie Buck | Republican | Henderson | 2020 | 2028 |

| 6 | 34, 37 | Nicole Cannizzaro | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2016 | 20282 |

| 7 | 18, 20 | Roberta Lange | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2020 | 2028 |

| 8 | 2, 5 | Marilyn Dondero Loop | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2018 | 2026 |

| 9 | 9, 42 | Melanie Scheible | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2018 | 2026 |

| 10 | 15, 16 | Fabian Doñate | Democratic | Las Vegas | 20211 | 2026 |

| 11 | 8, 35 | Lori Rogich | Republican | Las Vegas | 2024 | 2028 |

| 12 | 21, 41 | Julie Pazina | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2022 | 2026 |

| 13 | 24, 30 | Skip Daly | Democratic | Sparks | 2022 | 2026 |

| 14 | 31, 32 | Ira Hansen | Republican | Sparks | 2018 | 2026 |

| 15 | 25, 27 | Angie Taylor | Democratic | Reno | 2024 | 2028 |

| 16 | 26, 40 | Lisa Krasner | Republican | Reno | 2022 | 2026 |

| 17 | 38, 39 | Robin Titus | Republican | Wellington | 2022 | 2026 |

| 18 | 4, 13 | John Steinbeck | Republican | Las Vegas | 2024 | 2028 |

| 19 | 33, 36 | John Ellison | Republican | Elko | 2024 | 2028 |

| 20 | 19, 23 | Jeff Stone | Republican | Las Vegas | 2022 | 2026 |

| 21 | 12, 14 | James Ohrenschall | Democratic | Las Vegas | 2018 | 2026 |

- 1 Senator was originally appointed.

- 2 Due to term limits in the Nevada Constitution this individual is not eligible for re-election or appointment to the Nevada Senate

Senate standing committees of the 83rd session

[edit]| Committee | Chair | Vice Chair | Ranking Member | Number of members |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commerce and Labor | Julie Pazina | Skip Daly | John Ellison | 8 |

| Education | Angie Taylor | Marilyn Dondero Loop | Robin Titus | 8 |

| Finance | Marilyn Dondero Loop | Rochelle Nguyen | Robin Titus | 8 |

| Government Affairs | Edgar Flores | James Ohrenschall | Lisa Krasner | 7 |

| Growth and Infrastructure | Rochelle Nguyen | Julie Pazina | Ira Hansen | 5 |

| Health and Human Services | Fabian Doñate | Angie Taylor | Robin Titus | 5 |

| Judiciary | Melanie Scheible | Edgar Flores | Lisa Krasner | 8 |

| Legislative Operations and Elections | James Ohrenschall | Skip Daly | Lisa Krasner | 5 |

| Natural Resources | Michelee Crawford | Melanie Scheible | Ira Hansen | 5 |

| Revenue and Economic Development | Dina Neal | Fabian Doñate | Jeff Stone | 5 |

Standing committees in the Senate have their jurisdiction set by the Senate Rules as adopted through Senate Resolution 1. To see an overview of the jurisdictions of standing committees in the Senate, see Standing Rules of the Senate, Section V, Rule 40.

Past composition of the Senate

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Nevada State Senate - 2011 Districts" (PDF). Legislative Counsel Bureau. January 6, 2012.

- ^ "Nevada Constitution". Legislative Counsel Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ "Nevada Constitution". Legislative Counsel Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ "Political History of Nevada" (PDF). Nevada State Printing Office. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ "Political History of Nevada" (PDF). Nevada State Printing Office. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Dungan v. Sawyer, 250 F.Supp. 480 (1965)

- ^ Dungan v. Sawyer, 250 F.Supp. 480 (1965)

- ^ "Political History of Nevada, Pages 284-286" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Sen. William Raggio (January 5, 2012). "Letter to Washoe County Commission" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Leslie Resigns State Senate Seat to Run in New District 15". Las Vegas Review Journal. February 15, 2012.

- ^ "Republican Halseth Resigning Senate Seat". Las Vegas Review Journal. February 17, 2012.

- ^ Election results. State legislators in Nevada assume office the day after the election.

- ^ Democrats Tick Segerblom (District 3) and Aaron D. Ford (District 11) resigned in order to take office as Clark County Commissioner and Attorney General of Nevada, respectively. The Clark County Commission selected Democrats Chris Brooks and Dallas Harris respectively to succeed them in the Senate. [1]

- ^ Democrat Kelvin Atkinson (District 4) resigned. [2]

- ^ Democrat Marcia Washington appointed to replace Atkinson. [3]

- ^ Republican Scott Hammond (District 18) resigned. [4]

- ^ Sean Whaley (May 25, 2010). "In Surprise Move, State Senate Majority Leader Replaces Long-Time Top Staffer". Nevada News Bureau.

- ^ "Nevada Senate Majority Leader Picks Census Bureau Liaison to Serve in Top Administrative Post". Nevada News Bureau. August 18, 2010. Archived from the original on December 16, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ "Claire Clift to return as Senate Secretary". Nevada Appeal. November 8, 2014.

- ^ Redistricting in Nevada

External links

[edit]- Nevada Senate official government website

- Project Vote Smart – State Senate of Nevada

Nevada Senate

View on GrokipediaHistory

Establishment and early statehood (1864–1900)

Nevada achieved statehood on October 31, 1864, following the Enabling Act passed by Congress on March 21, 1864, which authorized the territory to draft a constitution and establish a state government, including a bicameral legislature comprising a Senate and an Assembly.[7][8] The constitutional convention convened in Carson City from July 4 to July 28, 1864, where delegates, predominantly influenced by mining interests from the Comstock Lode region, framed the document emphasizing limited government and property protections to foster economic growth.[1] Article IV of the constitution vested legislative power in the Senate and Assembly, stipulating that senators must be at least 25 years old, qualified electors resident in their district for one year, and elected for four-year terms, with half the seats up for election biennially alongside the Assembly.[9] The initial Senate consisted of 18 members, apportioned among Nevada's counties based on population to reflect the demographic weight of mining hubs, with Storey County—home to Virginia City's Comstock Lode—allocated five seats due to its roughly 21,000 residents, while smaller rural counties like Douglas, Lyon, and Humboldt received one each.[8][10] This population-based scheme, mandated by Article I, Section 13, prioritized empirical representation from productive areas but sparked debates at the convention over balancing urban mining centers against sparse agricultural districts, as rural delegates argued for safeguards against dominance by boomtown interests.[11] The first legislative session assembled on December 12, 1864, in Carson City, promptly electing U.S. Senators William M. Stewart and James W. Nye, and enacting foundational statutes on county organization and judicial procedures.[10] Early senatorial proceedings centered on legislation supportive of the silver-driven economy, including clarifications on mining claim rights and exemptions for infrastructure development to access Comstock ore bodies, reflecting a commitment to property rights over expansive regulation.[12] Convention debates on taxation highlighted causal tensions: mining advocates, fearing high assessments would repel capital, prevailed in adopting Article X's provision for taxing only net proceeds from mines rather than valuing undeveloped claims as real property, a compromise from the failed 1863 constitution that had proposed broader levies and risked alienating investors amid the Lode's 1859 discovery boom.[13][14] This net-proceeds approach, debated extensively as essential for revenue without stifling exploration, underscored empirical priorities of sustaining output—peaking at over 400 million ounces of silver by 1877—while minimizing government interference, though it drew criticism from non-mining delegates for underfunding homestead and road initiatives.[15] Through the 1870s and 1880s, the Senate iteratively refined claim laws and territorial expansions, adapting to bust cycles by prioritizing fiscal restraint and resource extraction over redistributive policies.[8]Silver boom, bust, and progressive reforms (1901–1940)

The Nevada Legislature, including the Senate, navigated economic volatility stemming from the lingering effects of the 1893 silver panic, which had halved the state's population to 42,335 by 1900 and entrenched fiscal dependency on mining revenues. Discoveries of gold and silver in Tonopah in May 1900 and Goldfield in December 1902 ignited a new boom, spurring population growth to over 80,000 by 1910 and prompting Senate-backed policies to sustain extraction, such as streamlined mining claims and infrastructure investments that prioritized industry recovery over expansive regulation.[16] These measures reflected fiscal realism, as commodity price swings—exacerbated by federal monetary policies post-Sherman Silver Purchase Act repeal—necessitated pragmatic relief to avert further depopulation and state insolvency.[17] Progressive influences permeated legislative agendas, yielding reforms like women's suffrage; in 1913, the Senate concurred with the Assembly to pass Senate Joint Resolution No. 1, amending the state constitution to enfranchise women, which male voters ratified on November 3, 1914, by a margin of 10,367 to 7,774.[18] Labor laws advanced worker protections amid mining's hazards, including eight-hour day mandates for certain industries by 1911, yet these coexisted with union militancy that critics argued stifled innovation; the 1906–1907 Goldfield strikes, involving over 1,000 miners demanding closed shops and higher wages, escalated to violence, prompted federal troop intervention under President Theodore Roosevelt in December 1907, and accelerated the boom's collapse by deterring capital investment and prolonging economic disruption.[19] Efforts to diversify beyond mining included irrigation initiatives, with the Legislature enacting water rights frameworks to leverage federal reclamation; following the 1902 Newlands Reclamation Act, state sessions authorized cooperative agreements and surveys enabling projects like the Truckee-Carson system, which irrigated 130,000 acres by the 1920s and reduced reliance on arid federal land sales.[20] By the Great Depression, economic imperatives reversed prior progressive moralism—gambling had been banned statewide in 1910—leading the Senate to approve Assembly Bill 98 on March 17, 1931, legalizing casinos and other games to generate licensing fees exceeding $500,000 annually by 1932, forging a causal pathway to tourism-driven resilience against extractive busts.[21][22]Postwar expansion and federal relations (1941–1966)

Following World War II, Nevada's population surged from 110,247 in 1940 to 285,278 by 1960, a 78 percent increase fueled by the expansion of military installations such as Nellis Air Force Base and Stead Air Force Base, the establishment of the Nevada Test Site for atomic testing in 1951, and the postwar boom in legalized gaming and tourism concentrated in Clark and Washoe Counties, which accounted for approximately 75 percent of the state's residents by 1960.[23] This demographic shift strained the biennial legislative sessions, which had historically been limited to 60 days but increasingly addressed complex issues like infrastructure and regulation, prompting the creation of the nonpartisan Legislative Counsel Bureau in 1945 to provide research and drafting support to senators and assembly members.[23] The Nevada Senate, consisting of 17 members elected to four-year staggered terms across multi-county districts, played a key role in enacting measures to accommodate growth, including the 1955 Sales and Use Tax Act imposing a 2 percent levy to fund highways and public services, which voters upheld in a 1956 referendum.[23] The Senate prioritized regulatory frameworks for the gaming industry, which generated substantial revenue amid postwar tourism and casino proliferation in Las Vegas. In 1955, senators approved legislation establishing the Gaming Control Board within the Nevada Tax Commission to license operators, enforce licensing requirements, and combat organized crime infiltration, marking a shift from lax prewar oversight to structured state supervision that stabilized the sector and attracted investment.[24] This built on earlier wartime expansions, where federal military spending had indirectly bolstered gaming as a recreational outlet for personnel, with Senate Finance Committee deliberations emphasizing fiscal sustainability over moralistic restrictions.[23] Federal relations intensified as Nevada's economy became intertwined with national defense priorities, with atomic testing at the Nevada Test Site—initiated under federal auspices in 1951—injecting jobs and infrastructure funding into rural Nye County while prompting Senate oversight on environmental and safety concerns through appropriations for state monitoring.[23] Military bases contributed over 20 percent of state payroll by the mid-1950s, leading the Senate to pass tax incentive bills and resolutions supporting federal expansions, such as exemptions for government contractors under the 1942 constitutional amendment on intangible property taxes.[23] These interactions underscored Nevada's reliance on federal grants for highways and water projects, exemplified by the Senate's approval in the 1964 special session of the Southern Nevada Water Project, a federal-state compact leveraging Colorado River allocations to supply growing urban centers, facilitated by U.S. Senator Alan Bible's advocacy and President Lyndon Johnson's administration.[23] By the mid-1960s, urban-rural imbalances—exacerbated by southern Nevada's dominance—fueled reapportionment debates in the Senate, culminating in the 1961 Reapportionment Act maintaining 17 senators but facing legal challenges for malapportionment, with deviations exceeding 100 percent in some districts favoring rural areas.[23] A 1965 special session (October 25–November 13) proposed expanding to 20 senators across 13 districts to align with population centers, though implementation awaited court approval on March 21, 1966, reflecting the Senate's adaptation to postwar federal-driven urbanization without altering its fixed-term structure.[23] Special sessions in 1954 and 1956 further addressed education funding shortfalls, with the Senate enacting a revised school code to expand facilities amid influxes from federal workers' families.[23]Reapportionment, professionalization, and modern partisanship (1967–present)

The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Reynolds v. Sims (1964) mandated that state legislative districts be apportioned on the basis of substantially equal populations, overturning prior malapportionment in Nevada that had disproportionately favored rural counties over urban centers.[25][6] Prior to this, Nevada's districts, last significantly adjusted in 1961, reflected outdated population distributions from decades earlier, granting rural areas outsized influence despite the rapid growth of Clark County following World War II.[6] In response, the 1965 Nevada Legislature redrew districts using 1960 census data to achieve near-equal population sizes, fundamentally shifting power toward urban Las Vegas and diluting the per capita voice of sparsely populated rural districts—a causal outcome of enforcing "one person, one vote" amid uneven demographic expansion.[26] This reapportionment amplified urban priorities in legislative agendas, as Clark County's population surged from 16% of the state total in 1940 to over 60% by the 1990s, driven by tourism, gaming, and migration.[27] Rural-dominated coalitions, which had historically blocked progressive reforms, faced structural erosion, enabling debates on taxation, water rights, and infrastructure to increasingly reflect metropolitan interests. Subsequent redistricting cycles, tied to decennial censuses, reinforced this trend, with independent commissions post-2000 attempting to mitigate gerrymandering claims while adhering to equal-population standards.[28] Professionalization accelerated in the late 1960s and 1970s through expanded nonpartisan staff, including the creation of the Legislative Counsel Bureau's research division in 1965, which provided policy analysis and fiscal notes previously absent in Nevada's citizen legislature.[23] Sessions, constitutionally limited to 120 days biennially, effectively lengthened due to complex bills on gaming regulation and federal land use, with lawmakers receiving modest per diems rather than salaries until incremental increases in the 1980s. Bill passage rates hovered around 20-30% of introduced measures, reflecting selective output amid part-time service, though staff augmentation raised legislative capacity without full-time conversion.[29] Partisan dynamics sharpened post-reapportionment, with Republicans capturing Senate control in 1992 (11-10 margin) amid economic booms, advancing property tax caps and business incentives that aligned with Nevada's no-income-tax model.[30] Democrats, bolstered by public employee unions, countered with expansions in education funding and workers' protections during their 2000s majorities, as urban growth translated into voter registration edges—Democrats leading by up to 5% statewide until recent reversals.[27] By 2024, Democrats maintained a 13-8 Senate majority, empirically linked to Clark County's demographic weight, where non-citizen residents—counted in census-based apportionment—comprise higher shares (up to 13% above state averages in urban districts), potentially distorting per-citizen representation compared to rural areas.[31][32] This urban-rural divergence, exacerbated by national migration patterns including undocumented inflows inflating district populations without corresponding voting eligibility, has fueled critiques that mainstream analyses underemphasize causal distortions in citizen-weighted influence.[32] Recent Republican voter registration leads, overtaking Democrats in early 2025 for the first time since 2007, signal potential realignments tied to suburban shifts.[33]Powers, duties, and legislative process

Constitutional authority and structure

The Nevada Senate constitutes the upper chamber of the state's bicameral legislature, as delineated in Article 4 of the Nevada Constitution, which vests legislative authority jointly in the Senate and the Assembly to ensure divided powers and mutual checks against hasty or excessive enactments. Comprising 21 members elected from single-member districts apportioned decennially by population, the Senate's smaller size and staggered four-year terms— with half the seats up for election biennially—position it as a more deliberative body relative to the 42-member Assembly, fostering restraint in fiscal and policy matters aligned with the framers' intent for balanced representation.[1][2] Under Article 4, Section 18, all bills for raising revenue must originate in the Assembly, embedding a structural curb on Senate-initiated taxation or spending expansions and compelling the upper house to amend or reject such measures, thereby reinforcing empirical limits on government growth through bicameral friction. The Senate further exercises confirmatory authority over gubernatorial appointments to executive boards and commissions, as provided in Article 5, Section 8, serving as a safeguard against unchecked executive discretion without extending to judicial or legislative posts. Gubernatorial vetoes, including line-item vetoes on appropriation bills under Article 5, Section 16, require a two-thirds supermajority in both chambers for override, a threshold that has historically constrained legislative dominance, with successful overrides occurring in under 5% of vetoed bills across most administrations except during the outlier tenure of Governor Jim Gibbons (2007–2011), when partisan supermajorities enabled 25 overrides amid fiscal crises.[1][34][35] Article 19 of the constitution empowers direct popular initiative and referendum, enabling qualified voters—through petitions signed by 10% (for statutes) or 5% (for amendments) of the preceding general election's turnout—to propose laws or constitutional changes that bypass the Senate and Assembly entirely if approved by voters, thus empirically reducing legislative overreach and aligning policy more closely with citizen preferences independent of elite capture. This mechanism, operational since 1912 amendments, has resulted in over 100 ballot measures since inception, including fiscal restraints like the 1996 Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR), underscoring causal checks on Senate authority via voter sovereignty rather than institutional expansion.[1][36]Bill passage, vetoes, and overrides

Bills in the Nevada Senate originate through introduction by a senator or, less commonly, via initiative from the Assembly or governor's request. Following introduction and first reading, bills are referred for committee consideration before advancing to second and third readings on the floor, where debate occurs under time limits set by standing rules that preclude filibusters, ensuring majority rule efficiency. A simple majority quorum—11 of 21 senators—must be present for proceedings, and passage requires a majority vote of 11 senators for most measures, escalating to two-thirds (14 votes) for bills raising taxes or fees. Upon Senate passage, bills proceed to the Assembly for concurrence or amendment, with any differences resolved via conference committee before final approval in both chambers.[37][38][39] Enacted bills reach the governor, who has five business days (excluding Sundays) during session or ten days post-adjournment to sign, veto, or allow automatic enactment without signature. Nevada's governor lacks line-item veto authority, requiring rejection of entire bills, including appropriations measures, to exercise restraint. A veto returns the bill with objections to the originating house; override demands a two-thirds majority in both chambers—14 senators and 28 assembly members—reaffirming constitutional checks against hasty legislation. Post-session vetoes become pocket vetoes if not overridden in a special session convened by legislative petition.[40][41][42] In practice, vetoes serve as a fiscal counterweight in divided government, as evidenced by Republican Governor Joe Lombardo's 87 vetoes during the 2025 session—the highest single-session total in state history—targeting expenditures from the Democrat-controlled legislature amid budget pressures. Of 605 bills received, 518 were signed into law, with vetoes often citing redundancy or unchecked spending, such as expansions in paid leave or regulatory mandates. Override attempts failed across sessions, including 2025, due to insufficient Republican support in the Senate, illustrating how partisan divides enforce veto efficacy over unified legislative dominance, though critics from Democratic lawmakers argue it obstructs bipartisan priorities like mental health funding.[43][44][45]Committee system and oversight functions

The Nevada Senate employs a committee system comprising ten standing committees to scrutinize and process legislation, with each committee assigned jurisdiction over designated policy domains such as finance, judiciary, education, and natural resources. Chairs and vice chairs are appointed by the Senate Majority Leader from the majority party, ensuring alignment with the chamber's partisan control; in the 83rd Session (2025), Democrats held the majority and thus occupied all chair positions. Committees hold public hearings to evaluate bills, solicit testimony from stakeholders, and assess fiscal impacts, often serving as a bottleneck where proposals undergo detailed examination for evidentiary support and causal linkages to intended outcomes. This structure processed over 1,000 measures in the 2025 session, with committees recommending amendments or tabling bills lacking substantiated cost-benefit rationales.[46][47][48] The Committee on Finance, for example, oversees appropriations and revenue measures, conducting hearings on budget shortfalls; during the 2025 session, it reviewed supplemental appropriations to address unanticipated deficits, such as a shortfall in the Office of the Secretary of State's operating expenses, while ultimately trimming more than $450 million from the governor's proposed $12.4 billion two-year budget to prioritize fiscal restraint. Similarly, the Committee on Education scrutinizes school funding proposals, evaluating allocations amid persistent debates over inefficiencies in per-pupil spending, where Nevada's rankings in national assessments underscore the need for outcome-based reforms rather than incremental expansions. These processes enforce empirical scrutiny, frequently stalling legislation advanced by advocacy without rigorous data on long-term efficacy or unintended fiscal burdens.[49][50] Oversight responsibilities extend to confirming limited gubernatorial appointments—only one executive position requires Senate approval—and supporting audits of state agencies through the Legislature's independent Audit Division, which identifies fiscal mismanagement and improper practices. Audits have revealed deficiencies in agency record-keeping and illegal transactions, prompting committee recommendations for corrective actions, including in sectors like education where spending inefficiencies, such as misallocated resources without tied performance metrics, have been flagged for reform. Critics from minority party perspectives argue that majority control can lead to partisan delays in oversight probes, yet the system's transparency via public records and hearings mitigates such risks by mandating evidence-based deliberations over ideological priors.[51][52][53]Elections and membership

Qualifications, terms, and districting

Candidates for the Nevada State Senate must be at least 21 years of age, a qualified elector in the district they seek to represent, and a resident of Nevada for at least one year preceding the election.[54] Qualified electors are U.S. citizens aged 18 or older who have resided in Nevada for 30 days and registered to vote.[54] State senators serve four-year terms with no consecutive term limit restriction within the Senate itself, though a 1996 voter-approved constitutional amendment imposes a lifetime cap of 12 years of service in the Senate (equivalent to three full terms).[55] This contrasts with the Nevada Assembly, where two-year terms and a 12-year lifetime limit (six terms) were similarly enacted, fostering legislative turnover while allowing senators extended individual tenure compared to assembly members.[56] The Nevada Senate comprises 21 single-member districts, reapportioned decennially to reflect population changes from the U.S. Census and ensure approximate equality of representation, with each district averaging around 140,000 residents as of the 2020 census.[57] Following the 2020 census, the Democratic-majority legislature passed Senate Bill 1 in a November 2021 special session, establishing new boundaries signed into law by the governor; these maps emphasize contiguity, compactness, and preservation of communities of interest as required by state criteria.[58] Legal challenges, such as Koenig v. Nevada filed in 2022 alleging violations of compactness, contiguity, and equal protection under the state constitution, were unsuccessful, with courts upholding the maps and resulting in fewer disruptions than in states facing multiple overturned plans or independent commissions.[59] Senate elections are staggered, with 10 or 11 seats (alternating due to the odd total) contested biennially in even-numbered years, ensuring at least partial continuity of membership across legislative sessions.[31] This structure intersects with voter turnout patterns showing urban-rural divides, where densely populated urban districts in counties like Clark exhibit higher participation rates—often exceeding 60% in midterm elections—compared to rural areas with sparser populations and turnout below 50%, potentially skewing representational equity toward metropolitan influences amid logistical barriers to rural voting.[60]Electoral history and apportionment controversies

The Nevada State Senate exhibited Republican majorities in numerous sessions during the early and mid-20th century, aligned with the state's rural, mining-dependent electorate and conservative leanings outside urban centers.[28] This pattern persisted until population surges in Clark County—driven by Las Vegas's expansion—tilted demographics toward Democrats, enabling their first modern control in the 1990s amid national Democratic gains.[61] Post-2000, control alternated: Republicans regained it in 2000 and held through 2010, reflecting backlash to economic downturns and federal policies, before Democrats secured slim majorities from 2012 onward, solidified by 2018 through targeted wins in urban and suburban districts.[62] Recent elections underscore Clark County's decisive role, where Democratic margins often determine statewide outcomes. In the 2024 cycle, Democrats preserved a 13-8 edge despite Donald Trump's statewide presidential victory—the first Republican win in Nevada since 2004—and a broader GOP surge nationally. Key districts in Clark, such as Senate District 1 and District 6, saw Democratic incumbents prevail by under 5% in several races, offsetting Republican gains in rural northern Nevada; for instance, GOP candidates captured seats in Districts 9 and 17 by similar narrow margins, but urban turnout preserved the majority.[63] This resilience highlights empirical reliance on high-density voter bases rather than statewide ideological shifts, with Democrats averaging 52-55% in Clark-heavy contests amid 60%+ turnout.[64] Apportionment disputes have centered on post-census redistricting, with both parties filing suits alleging unfair maps. After the 2020 census, a Democratic legislative supermajority enacted Senate Bill 1 in a 2021 special session, redrawing districts that critics, including Republican voters in Koenig v. Nevada, claimed diluted rural GOP strength through urban packing—concentrating conservative voters into fewer districts while cracking others.[65][59] Courts largely upheld the plans for compactness and population equality, rejecting partisan gerrymander claims absent Nevada-specific constitutional prohibitions, though empirical metrics like the efficiency gap showed modest Democratic advantages (around 4-6% statewide).[66] Historical precedents include 1980s Republican challenges to Democratic maps post-apportionment, but data indicate districts generally adhere to contiguous, compact standards under state law, countering narratives of egregious manipulation.[6] Efforts to reform via independent commissions faced setbacks, including the Nevada Supreme Court's 2024 invalidation of ballot initiatives for violating single-subject rules, preserving legislative control despite public support for depoliticization.[67] Voter-approved Question 3 in 2022, aiming for open (top-five) primaries and ranked-choice voting in generals, was rejected in 2024 by 56-44%, with opponents arguing it could exacerbate strategic abstentions without proven depolarization benefits in diverse electorates.[68][69] While proponents cited Alaska's model for moderating extremes, Nevada's rejection aligns with analyses questioning ranked-choice's causal impact on polarization, as underlying voter sorting—evident in Hispanic communities' rightward shift (e.g., 45% GOP support in 2024 exit polls)—drives divides more than mechanics.[70] Mainstream critiques often underemphasize such demographic realignments, favoring institutional fixes over evidence of organic preference changes.Voter turnout and demographic influences

Voter turnout in Nevada Senate elections, which occur during even-year general elections, has historically been lower in midterm cycles compared to presidential years, reflecting national patterns but amplified by the state's reliance on mail-in voting. In the 2022 midterm election, turnout reached 54.58% of active registered voters, with mail ballots comprising a significant portion due to Nevada's policy of automatically mailing ballots to all active voters since 2020.[71][72] This system has boosted overall participation by reducing barriers, though election-day voting remains under 25% of ballots in recent cycles.[73] Critiques highlight rural underrepresentation in turnout data, as sparse population centers in non-metro counties contribute fewer votes relative to urban hubs like Clark County, exacerbating disparities despite districting efforts to balance geographic influence.[72] Demographic patterns strongly shape outcomes, with urban areas driving Democratic support through Latino and union-heavy electorates, while rural and white conservative voters bolster Republicans. In Clark County, home to over 60% of Nevada's population, Latino voters—who constitute about 20% of the voting-age population—have trended Democratic, with turnout growth outpacing statewide averages and favoring progressive policies on labor and immigration.[74] Conversely, rural districts, encompassing vast federal lands that limit residential density and population growth, amplify conservative voices; federal ownership of approximately 81% of Nevada's land constrains rural development, preserving lower-density electorates that prioritize issues like land use and resource extraction, thereby enhancing per-capita rural electoral clout in Senate districting.[75] Union voters in Las Vegas hospitality sectors similarly tilt urban results Democratic, though economic shifts can mobilize working-class conservatives toward Republicans in off-cycle races.[60] Out-of-state funding influences Senate races through heavy PAC involvement, with both parties drawing criticism for rent-seeking behaviors that prioritize external interests over local priorities. Democratic-aligned unions and progressive groups often channel national resources to urban mobilization efforts, while Republican business PACs target rural and swing districts with ads on economic deregulation; in recent cycles, outside spending has exceeded local contributions, raising concerns about diluted voter sovereignty amid Nevada's battleground status.[76] Balanced analyses note that such inflows, while amplifying turnout via get-out-the-vote operations, can distort policy focus toward donor agendas, as evidenced by comparable escalations from labor federations and corporate entities in 2022 state legislative contests.[77]Sessions

Biennial and special sessions

The Nevada Legislature convenes in biennial regular sessions commencing on the first Monday in February of odd-numbered years, with each such session constitutionally limited to 120 consecutive calendar days, after which it must adjourn sine die no later than midnight Pacific time on the 120th day.[78][79] This structure, in place since 1867 except for an additional session in 1960, positions Nevada among only four U.S. states—alongside Montana, North Dakota, and Texas—that hold true biennial legislatures, concentrating substantive lawmaking in odd years while even-numbered years feature brief organizational meetings for swearing in members, electing officers, and adopting rules, typically lasting a few days.[79][80] Special sessions may be convened by proclamation of the governor for specified purposes, limited in scope to the call's agenda and generally capped at 20 consecutive calendar days, or by joint resolution of two-thirds of the membership of each house upon 10 days' notice.[81] These sessions have occurred 35 times since statehood, most recently in June 2023 (the 35th Special Session), when Governor Joe Lombardo called lawmakers to address budget-related matters following vetoes in the prior regular session, resulting in the passage of targeted appropriations bills over eight days.[81][82] Such sessions are invoked sparingly, often for fiscal emergencies or veto overrides, reflecting constitutional checks that constrain legislative activity compared to the federal Congress's indefinite sessions, thereby curbing potential over-legislation and aligning output with Nevada's part-time citizen legislature model.[81][83] During any session, the Senate and Assembly convene daily unless adjourned, with procedural rules mandating roll call, committee referrals for bills, and floor debates culminating in sine die adjournment upon time expiration or agenda completion.[79] Productivity under these limits averages hundreds of bills introduced per regular session, with passage rates around 40-50% in recent odd-year cycles—for instance, 267 of 605 bills enacted in 2021—equating to roughly 2-3 laws per day when accounting for the full 120-day span, a pace enabled by the fixed duration's focus on priorities like biennial budgeting. This temporal restraint, rooted in Article 4 of the state constitution, promotes efficiency by necessitating pre-session interim studies and discouraging extraneous measures, in contrast to annually meeting legislatures prone to protracted deliberations.[78][84]Key procedural rules

The Nevada Senate adheres to majority rule for passing bills and resolutions, requiring a simple majority on final passage via recorded vote, which can be demanded by any three senators. Unlike the U.S. Senate, it employs no filibuster, limiting debate to two speeches per senator per day on any question, with a motion for the previous question—demanded by at least three senators—ending further discussion upon majority approval. Amendments on the floor must remain germane, barring the introduction of unrelated subjects or irrelevant material to maintain focus on the underlying bill.[39] Overriding a gubernatorial veto demands a two-thirds supermajority of 14 votes in the 21-member chamber, a high bar reflected in historical rarity: only ten such overrides have succeeded in subsequent legislative sessions since statehood, underscoring the procedural emphasis on consensus for extraordinary actions.[85][86] Ethics and decorum fall under the bipartisan Senate Committee on Ethics, composed of two majority-party senators, one minority-party senator, and three non-legislative electors, which conducts confidential investigations into complaints of misconduct, conflicts of interest, or breaches like harassment and dishonesty, with authority to recommend sanctions including censure or penalties.[87][39] Post-COVID-19 adaptations include Rule 136, authorizing remote-technology participation and voting in exceptional circumstances—restricted to in-state locations and requiring Majority Leader approval—allowing senators to be deemed present without physical attendance during emergencies like the pandemic.[39][88]83rd Session (2025): Major bills, vetoes, and outcomes

The 83rd Session of the Nevada Legislature convened on February 3, 2025, and adjourned sine die on June 3, 2025, after 120 days of deliberations. Lawmakers introduced over 500 bills, with hundreds passing both chambers and reaching Governor Joe Lombardo's desk for consideration. The session focused on the biennial budget for fiscal years 2025-2027, education reforms, health care expansions, and public safety measures, amid a divided government where Democrats held majorities in both the Senate (13-8) and Assembly (27-15). Key budget legislation allocated $2.6 billion to the newly established Nevada Health Authority for Medicaid administration and mental health services, alongside funding for state operations through five major appropriations bills passed in the session's final weeks.[89][90][91] Among the enacted measures were education priorities such as Senate Bill 460, an omnibus bill addressing school funding and operations; Assembly Bill 398, providing pay raises for charter school teachers; and Assembly Bill 224, authorizing $100 million in bonds for capital improvements in rural school districts. Public safety and technology bills included Assembly Bill 527 for enhanced school bus safety protocols and Assembly Bill 406, imposing restrictions on artificial intelligence applications in certain contexts. These outcomes reflected Democratic legislative priorities in expanding social services and infrastructure, with nearly 200 new laws taking effect on July 1, 2025. However, attempts at broader tax relief, such as property tax abatements or gaming revenue reallocations, failed to advance amid partisan disputes, as evidenced by the lack of passage for Republican-backed fiscal restraint proposals.[92][93] Governor Lombardo vetoed a record 87 bills, surpassing his 2023 mark of 75, primarily targeting spending expansions in education, health care, and labor provisions that he argued exceeded fiscal capacity given Nevada's reliance on volatile sales and gaming taxes without an income tax. Notable vetoes included measures for paid family leave expansions, in vitro fertilization mandates, gun safety restrictions near polling places, voter ID requirements, and ballot drop box expansions—many of which Lombardo cited as either infringing on Second Amendment rights or imposing unfunded mandates amid projected budget pressures. These actions effectively curbed an estimated additional $500 million in potential expenditures, contributing to a biennial budget with restrained growth of approximately 4% over the prior cycle, prioritizing operational stability over expansive programs. No veto overrides occurred, as the legislature lacked the required two-thirds supermajorities in both chambers post-adjournment.[44][94][95][96] The session's outcomes underscored the checks of divided government, with Lombardo's vetoes serving as a mechanism to align policy with empirical fiscal constraints, including a structural deficit risk from tourism-dependent revenues. While Democratic sources highlighted advancements in health and education equity, Republican critiques emphasized the vetoes' role in averting unsustainable debt accumulation, supported by data showing Nevada's general fund reserves holding steady at around $1.5 billion post-session. Water rights reforms, including clarifications on groundwater allocation amid drought conditions, advanced modestly through targeted bills but faced limitations without comprehensive bipartisan consensus. Overall, the 83rd Session resulted in incremental policy shifts rather than transformative changes, reflecting causal tensions between legislative spending impulses and executive fiscal realism.[97][98]Leadership and organization

Presiding officers and nonpartisan roles

The Lieutenant Governor of Nevada serves as President of the Senate pursuant to Article 5, Section 17 of the state constitution, presiding over daily proceedings, maintaining order through gavel authority, and managing the legislative calendar during sessions.[99] In this capacity, the President holds no voting rights as a non-member except to break ties, a mechanism designed to resolve deadlocks without altering the elected composition of the body.[100] This role promotes institutional stability by separating executive oversight from partisan legislative voting, ensuring procedural decisions remain insulated from caucus pressures.[28] When the Lieutenant Governor is absent, the Senate elects a President pro tempore from its members to preside, continuing the chain of neutral facilitation over debate and quorum calls.[28] Complementing these positions are non-member officers focused on administrative and enforcement functions. The Secretary of the Senate, elected by the body at the session's outset, oversees employee assignments, records legislative proceedings, and handles bill processing to support efficient operations.[101] The Sergeant at Arms enforces chamber rules, supervises security, and executes directives from presiding officers to uphold decorum and access protocols.[102] These roles, held by nonpartisan staff or statewide officers, foster continuity across sessions and prevent procedural capture by transient majorities, as evidenced by their statutory duties independent of party affiliation.[103] Senate employees under these officers operate without partisan advocacy, prioritizing rule enforcement and record-keeping to sustain deliberative integrity.[104]Majority and minority party leadership

The Democratic majority in the Nevada Senate elects its leadership through internal caucus votes following general elections, with positions allocated to coordinate floor strategy, bill prioritization, and party cohesion during sessions.[105] As of November 2024, Senator Nicole Cannizzaro (D-District 6) was selected as Majority Leader for the 83rd Legislative Session starting in 2025, marking her fourth consecutive term in the role; she oversees agenda setting and Democratic messaging on key issues like education and taxation.[106] Supporting roles include Assistant Majority Leader Roberta Lange (D), Chief Majority Whip Melanie Scheible (D), and Deputy Majority Whip Fabian Doñate (D), who enforce party discipline and manage procedural votes.[107] These positions centralize influence within the 13-seat Democratic caucus, enabling control over debate schedules and resource allocation, though Senate Standing Rules mandate opportunities for minority amendments on non-fiscal bills to prevent unilateral dominance.[105] The Republican minority, holding 8 seats in the 2025 session, similarly selects leaders via caucus election to formulate opposition tactics, including blocking measures through procedural delays and amendments.[108] Senator Robin Titus (R-District 17) serves as Minority Leader, a role she assumed following the 2024 elections to represent GOP priorities such as fiscal restraint and regulatory reform amid Democratic majorities.[109] While specific whip and caucus chair announcements for Republicans were not publicly detailed in early 2025 organizational meetings, these roles typically assist the leader in rallying votes and crafting counter-strategies, with influence derived from Senate rules granting the minority guaranteed debate time and amendment rights on select legislation.[105] Critics, including Republican lawmakers, have noted that majority control can concentrate power in leadership hands, potentially sidelining rank-and-file input, but procedural safeguards like roll-call voting requirements help mitigate this by ensuring transparency in decision-making.[110]Standing committees and their jurisdictions

The Nevada Senate maintains ten standing committees as defined in Senate Standing Rule 40, which delineate their jurisdictions based on Nevada Revised Statutes (NRS) titles and chapters relevant to policy areas.[39] These committees conduct hearings, propose amendments, and recommend bills for floor consideration, with empirical scrutiny often revealing implementation flaws in proposals through stakeholder testimony and fiscal analyses; for instance, delays in committee advancement have historically filtered out measures lacking viable causal mechanisms for intended outcomes, countering claims of mere partisan obstruction.[111] In the 83rd Session (2025), Democratic majorities post-caucus assigned chairs to align with party priorities, yet committees processed over 500 bills referred to them, originating key fiscal and regulatory reforms after evidentiary review.[112] Core committees include Finance, which oversees appropriations, operating and capital budgets, and measures under NRS chapters 1A, 387, and 400, including education funding allocations exceeding $10 billion annually.[111] Revenue and Economic Development handles taxation, revenue generation, and economic incentives under NRS title 32 and chapters 360-371, scrutinizing gaming taxes that comprise 40% of state general fund revenue and mining royalties tied to Nevada's 5% gross proceeds tax on minerals.[113] Natural Resources addresses environmental protection, wildlife management, federal land use, and mining regulations under NRS titles 26 and 45-50, plus chapters 383, 407, and 407A, overseeing 86% of Nevada's land under federal jurisdiction and bills impacting lithium and gold extraction, which generated $4.5 billion in economic output in 2024.[114] Commerce and Labor reviews commercial transactions, labor relations, trade practices, and gaming oversight, processing regulations for Nevada's $15 billion gaming industry under NRS chapters on business and employment.[115] In practice, these panels' outputs—such as vetoed or amended bills in 2025—demonstrate rigorous vetting, where data on projected revenues or environmental impacts often deferred or revised hasty initiatives, prioritizing verifiable fiscal sustainability over expediency.[116]| Committee | Primary Jurisdiction |

|---|---|

| Finance | Budgets, appropriations (NRS ch. 1A, 387, 400)[111] |

| Revenue and Economic Development | Taxes, economic policy (NRS title 32, ch. 360-371)[113] |

| Natural Resources | Environment, mining, federal lands (NRS titles 26, 45-50; ch. 383, 407, 407A)[114] |

| Commerce and Labor | Gaming, labor, commercial rights[115] |

Current composition (as of 2025)

Partisan breakdown and vacancies

As of October 2025, the Nevada State Senate comprises 21 members, with Democrats holding 13 seats and Republicans 8 seats, securing a Democratic majority.[28][117] There are no current vacancies in the chamber.[118] The 2024 elections, which covered 10 districts, resulted in Democrats retaining their pre-election 13-8 advantage despite Republican victories in federal races nationwide, including Nevada's U.S. Senate seat flipping to the GOP.[119][117] Official results certified by the Nevada Secretary of State confirmed Democratic holds in key battleground districts, such as District 11 in urban Clark County.[63] This partisan balance reflects Nevada's voter registration dynamics, where Democrats maintain a narrow plurality over Republicans amid a large independent bloc, coupled with consistently higher turnout in Democratic-leaning urban centers like Las Vegas compared to rural areas.[120] Rural conservative perspectives, prevalent in counties like Nye and Elko, exert limited influence due to the chamber's districting, which amplifies urban voter weights.[121]Demographic profile of senators

As of October 2025, the Nevada Senate comprises 13 women and 8 men among its 21 members, marking a female majority that aligns with the state's legislative trends since achieving the nation's first female-majority assembly in 2019.[4][122] This gender composition exceeds the national average for state upper chambers, where women hold about 32% of seats, but stems from targeted recruitment rather than proportional district demographics, raising questions about whether such numerical diversity causally enhances policy outcomes in areas like economic regulation.[123] Ethnically, the Senate includes visible representation from Hispanic senators such as Fabian Doñate (District 10) and Edgar Flores (District 2), alongside Rochelle T. Nguyen (District 3) of Vietnamese descent, reflecting partial alignment with Nevada's population where Hispanics constitute 29.3% and Asians 10.5%.[4] However, white senators predominate, and no comprehensive ethnic census of members exists, potentially underrepresenting Black Nevadans (9.9% of population) despite urban district majorities in Clark County. Rural and mining constituencies, critical to Nevada's extractive economy (contributing over $10 billion annually as of 2023), lack direct worker representation, with senators from districts like 14 (Elko County) and 19 holding non-industry professions. Professional backgrounds skew toward law, public service, and education: at least eight senators are attorneys or former prosecutors (e.g., Nicole J. Cannizzaro, James Ohrenschall), while others include educators (e.g., Dina Neal, adjunct professor) and business owners in real estate or consulting.[124][125] This lawyer-heavy profile (over 38% of seats) mirrors national state legislative patterns but contrasts with empirical needs for expertise in Nevada's dominant sectors—gaming (52% of state tax revenue) and mining—where causal policy errors, such as overregulation stifling investment, may arise from disconnected professional lenses rather than ground-level operational knowledge. Post-2024 shifts added diverse voices like Carrie Ann Buck (Republican, business background), yet data from prior sessions links legislative effectiveness more to issue-specific experience than demographic quotas.[4][126]Key districts and recent shifts from 2024 elections

District 11 emerged as the most pivotal contest, where Republican Lori Rogich defeated Democratic incumbent Dallas Harris by a narrow margin of 50.7% to 49.3%, marking a partisan flip from Democratic to Republican control in this Clark County district encompassing parts of Las Vegas.[127] This shift reflected voter priorities on economic pressures, including high housing costs and property taxes, which polled as top concerns in suburban areas amid Nevada's tourism-dependent economy and post-pandemic recovery challenges.[128] Other competitive races included District 5 in southern Nevada, a Republican hold where incumbent Carrie Buck secured 53.5% against Democratic challenger Jennifer Atlas's 46.5%, bolstered by rural and exurban support in Nye and parts of Clark Counties.[127] In District 6, Democratic incumbent Nicole Cannizzaro held on with 51.7% over Republican Jill Douglass's 45.5%, maintaining urban Democratic strength in northern Las Vegas despite a tighter margin than pre-election forecasts. District 15, an open seat previously held by a Republican, flipped to Democrat Angie Taylor with 54.9% against Republican Michael Ginsburg, offsetting the District 11 loss through gains in Reno-area suburbs.| District | Incumbent Party | Winner | Winner Vote % | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Republican | Carrie Buck (R) | 53.5% | Hold |

| 6 | Democratic | Nicole Cannizzaro (D) | 51.7% | Hold |

| 11 | Democratic | Lori Rogich (R) | 50.7% | Flip to R |

| 15 | Republican (open) | Angie Taylor (D) | 54.9% | Flip to D |

Historical composition and partisan control

Evolution of party majorities

The partisan composition of the Nevada State Senate shifted toward Republican majorities in the 1990s following decades of Democratic control post-New Deal, reflecting statewide economic expansion and conservative voter mobilization.[61] Democrats regained control in 2008 amid a national electoral wave, briefly losing it in 2014 before securing it again in 2016 through a combination of urban voter turnout and a nonpartisan senator's caucus alignment.[28] Since then, Democrats have expanded their edge to 13-8, sustained by demographic changes including rapid growth in Clark County, where Latino and unionized service-sector populations have trended Democratic.[41] These transitions align with broader causal factors: Nevada's population boom, fueled by migration to Las Vegas for tourism and construction jobs, concentrated Democratic-leaning voters in urban districts, amplifying union influence from organizations like the Culinary Workers Union, which mobilizes reliably for Democrats.[61] Empirical data indicate that Democratic majorities have correlated with higher state spending growth—general fund appropriations rose from approximately $5.3 billion in fiscal year 2008 to over $11 billion by 2024—often directed toward education, Medicaid expansion, and public employee benefits, whereas Republican control periods featured veto-driven restraint under aligned governors.[129] Critics of sustained Democratic dominance argue that expansive fiscal policies overlook risks to Nevada's business-attracting no-income-tax model, potentially accelerating corporate relocations observed in high-tax states, though proponents attribute spending hikes to population-driven demands rather than partisan ideology.[130]| Election Year | Democrats | Republicans | Majority Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 10 | 11 | Republican |

| 1994 | 8 | 13 | Republican |

| 1996 | 9 | 12 | Republican |

| 1998 | 9 | 12 | Republican |

| 2000 | 9 | 12 | Republican |

| 2002 | 9 | 12 | Republican |

| 2004 | 9 | 12 | Republican |

| 2006 | 10 | 11 | Republican |

| 2008 | 12 | 9 | Democratic |

| 2010 | 11 | 10 | Democratic |

| 2012 | 11 | 10 | Democratic |

| 2014 | 10 | 11 | Republican |

| 2016 | 11 | 10 | Democratic |

| 2018 | 13 | 8 | Democratic |

| 2020 | 12 | 9 | Democratic |

| 2022 | 13 | 8 | Democratic |

| 2024 | 13 | 8 | Democratic |