Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geppetto

View on Wikipedia| Geppetto | |

|---|---|

| The Adventures of Pinocchio character | |

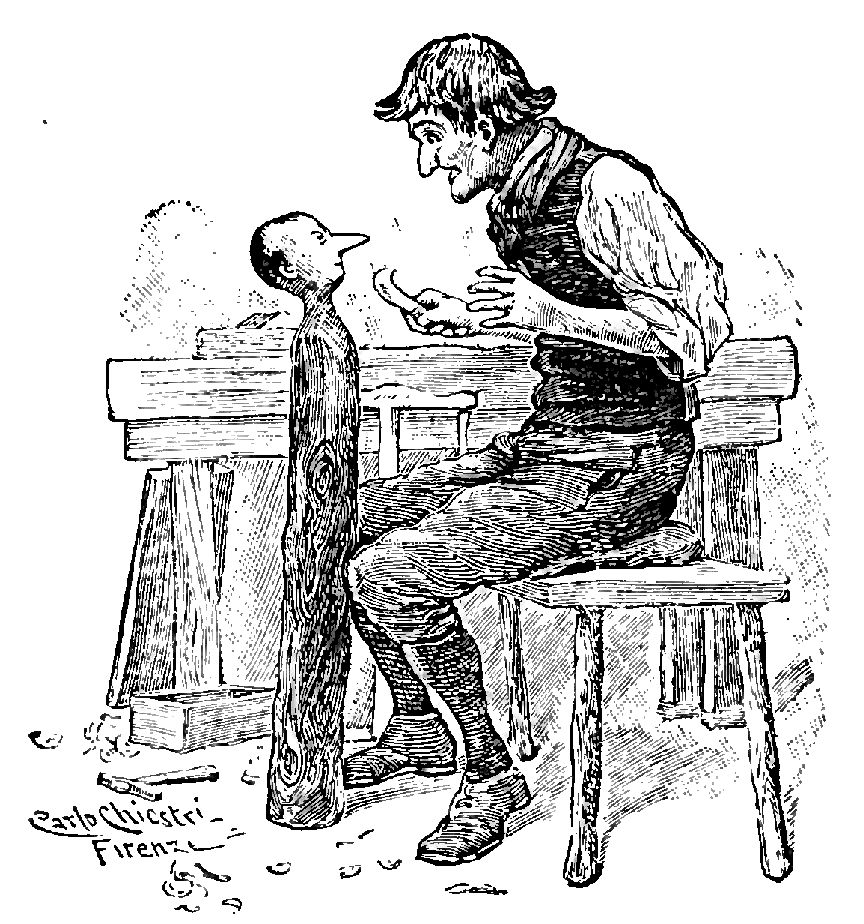

Geppetto carving Pinocchio. | |

| First appearance | The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883) |

| Created by | Carlo Collodi |

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Human |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Carpenter |

| Family | Pinocchio (son) |

| Nationality | Italian |

Geppetto (/dʒəˈpɛtoʊ/ jə-PET-oh; Italian: [dʒepˈpetto])[1] is a fictional character in the 1883 Italian novel The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi. Geppetto is an elderly, impoverished woodcarver and the creator (and thus 'father') of Pinocchio. He wears a yellow wig resembling cornmeal mush (called polendina), and consequently his neighbors call him "Polendina" to annoy him. The name Geppetto is a Tuscan diminutive of the name Giuseppe (Italian for Joseph).

Role

[edit]

Geppetto is introduced when carpenter Mister Antonio finds a talking block of pinewood that he was about to carve into a leg for his table. When Geppetto drops by looking for a piece of wood to build a marionette, Antonio gives the block to Geppetto.

Geppetto, being extremely poor and thinking of making a living as a puppeteer, carves the block into a boy and names him "Pinocchio." Before he is even built, Pinocchio already has a mischievous attitude; no sooner is Geppetto finished carving Pinocchio's feet than the puppet proceeds to kick him. Once the puppet has been finished and Geppetto teaches him to walk, Pinocchio runs out the door and away into the town. He is caught by the carabiniere. When people say that Geppetto dislikes children, the carabiniere assumes that Pinocchio has been treated poorly and imprisons Geppetto.

The next morning, Geppetto is released from jail and finds that Pinocchio's feet have burnt off. Geppetto replaces them with new feet. When Geppetto feeds him three pears, Pinocchio promises to go to school. Because Geppetto has no money to buy school books, he sells his only coat.

Geppetto is next seen when Pinocchio believes that the Fairy with Turquoise Hair has died and a pigeon carries him to the seashore, where Geppetto is building a boat to search for Pinocchio (depending on the version of the story he sails in search for Pinocchio on near islands or following Mangiafuoco and his puppet theatre headed to the Nuovo Mondo). Pinocchio tries to swim to Geppetto but is washed underwater while Geppetto is swallowed by the Terrible Dogfish.

Geppetto is not seen again until Pinocchio is himself swallowed. Pinocchio and Geppetto escape the Dogfish and are thence conveyed to shore by a tuna.

After several months of hard work supporting the ailing Geppetto at a farmer's house, Pinocchio goes to buy himself a new suit, and Geppetto and Pinocchio are not reunited until the puppet has become a boy. Geppetto is seen healthy again and resuming woodcarving.

Adaptations

[edit]Disney version

[edit]

In the 1940 Disney animated film, Geppetto is introduced as a shopkeeper finishing Pinocchio. Before falling asleep, Geppetto wishes upon on a star for Pinocchio to become a real boy. During the night, the Blue Fairy grants Geppetto's wish. The next day, he sends Pinocchio on his first day of school. On his way, Pinocchio meets Honest John and Gideon, who convince him to join Stromboli's puppet show instead, and then to go to Pleasure Island. When Pinocchio returns home, he finds the shop empty and full of dust and cobwebs, and learns from a letter by the Blue Fairy that Geppetto, venturing out to sea to rescue Pinocchio from Pleasure Island, had been swallowed by Monstro (a whale-like variation of The Terrible Dogfish). Determined to rescue his father, Pinocchio reunites with Geppetto and his pets inside Monstro, where Pinocchio burns spare furniture to choke their captor into releasing them. This done, Monstro pursues them to the coast, where Pinocchio pulls Geppetto to safety, but himself falls senseless. While Geppetto mourns Pinocchio at home, the Blue Fairy revives Pinocchio, and makes him human.

Geppetto appeared the following year in the short All Together (1942), made for the Canadian government.[3]

Disney's version of Geppetto has also made appearances in House of Mouse as well as in the Kingdom Hearts series of video games in the "Monstro" world. The character also made a cameo appearance alongside Pinocchio in the episode "Wonders of the Deep" of the Mickey Mouse TV show.

Tom Hanks plays Geppetto in the 2022 live-action/CGI adaptation of the film.[4] This version was shown to have a son who died.

Russian version

[edit]In the 1936 Soviet book adaptation The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Buratino by Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy, the character based on Geppetto is named Papa Carlo. He is an elderly organ grinder who lives in a tiny closet under a staircase, containing nothing but a painted fireplace on a piece of canvas. His barrel organ had long been broken, forcing him to survive on odd jobs. His only friend is Giuseppe the Blue Nose, an aging and perpetually drunk carpenter (based on Mastro Antonio), who gives Carlo a sentient log that he later carves into Buratino. Tolstoy likely used Carlo and Giuseppe as a satirical depiction of Russian theater practitioners Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, respectively.

In the 1959 animated adaptation of the book, Papa Carlo was voiced by Yevgeny Vesnik, while in the 1975 live-action adaptation, he was portrayed by Nikolai Grinko.

Television musical

[edit]Geppetto is the title character in the 2000 made-for-television musical, portrayed by Drew Carey. He dearly wishes to become a father until one night, the Blue Fairy appears in his workshop and brings Pinocchio to life. At first, Geppetto is happy that his wish came true, but runs into problems with Pinocchio asking persistent questions when trying to get to sleep, wandering off and getting into mischief when introducing him to the townspeople of Villagio, lying, and not interested in being a toymaker. The next day, Geppetto sends Pinocchio off to school, telling him to just act like all of the other children and he'll be alright. However, Pinocchio gets sent home from school after he gets into a fight for imitating all the other children, disappointing Geppetto. On their way home, they meet Stromboli the puppeteer who is fascinated by Pinocchio and thinks he would be worth a fortune to him as the main attraction in his puppet show.

After a brief confrontation with the Blue Fairy doesn't go well, Geppetto returns home, only to find out that Pinocchio ran away to live with Stromboli, who keeps him under a contract he had him sign. When Geppetto arrives after the show, Stromboli says Pinocchio left, claiming that he wanted to see the world, only to find Pinocchio running off to Pleasure Island and they both set out to find him. Along the way, Geppetto meets a magician named Lezarno and visits the town of Idylia where Professor Buonragazzo and his son make perfectly obedient children for any family that wants one. He then arrives at Pleasure Island and discovers the terrible curse it harnesses. After riding the roller coaster, the boys all "make jackasses of themselves" by turning into donkeys. He arrives at the roller coaster to rescue Pinocchio, but he refuses, saying he was a big disappointment to him, gets on the ride, and is shipped off to the salt mines after having been turned into a donkey. Geppetto, keeping up with the ship using a tiny fishing boat, suddenly gets swallowed by a monstrous whale where Pinocchio tells him that after he jumped in the water to save him, the donkey curse washed away and he became human again. After making up their misunderstanding, Pinocchio tells as many lies as he can, causing his nose to grow, which tickles the whale's uvula, causing it to throw them up. They then return home to Villagio, only to find Stromboli waiting to take Pinocchio back, still keeping him under the contract he signed earlier. Geppetto offers his entire shop in exchange, only for Stromboli to kidnap Pinocchio and Geppetto pleads and begs to the Blue Fairy, who can no longer help him, to grant him one last wish. The fairy then turns Pinocchio into a real boy, shoos Stromboli away with her magic, and transformed the words on the workshop sign to "Geppetto & Son," thus resulting in Pinocchio and Geppetto living happily ever after.

Fables

[edit]Geppetto is a major villain in the Fables comic series written by Bill Willingham and published by DC Comics. His actions are responsible for the entire premise of the comic book, in that he is the being known as "The Adversary" who masterminded the conquest of the Fable homelands, forcing the Fables to flee into the mundane world.[5]

Video games

[edit]Geppetto serves as one of two main antagonists, alongside Simon Manus, in the 2023 soulslike Lies of P developed by Neowiz Games and Round8 Studio and published by Neowiz. His actions are responsible for the puppet uprising that desolates the fictional city of Krat. He entrusts his creation P to enter the chaos to gather strength and retrieve an artifact in Simon's possession to enact a sinister resurrection plot for his deceased son, Carlo.

References

[edit]- ^ "Geppetto". Dizionario d'Ortografia e di Pronunzia. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- ^ "Fairy Tale Police Department - Episode 1 - Pinocchio: Puppet in Peril". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Roe, Bella Honess (2011). A. Bowdoin Van Riper (ed.). Learning from Mickey, Donald and Walt: Essays on Disney's Edutainment Films. McFarland. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7864-8475-1.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca (December 10, 2020). "'Pinocchio' With Tom Hanks, 'Peter Pan and Wendy' to Skip Theaters for Disney Plus". Variety. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Irvine, Alex (2008), "Fables", in Dougall, Alastair (ed.), The Vertigo Encyclopedia, New York: Dorling Kindersley, pp. 72–81, ISBN 978-0-7566-4122-1, OCLC 213309015