Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor

View on Wikipedia

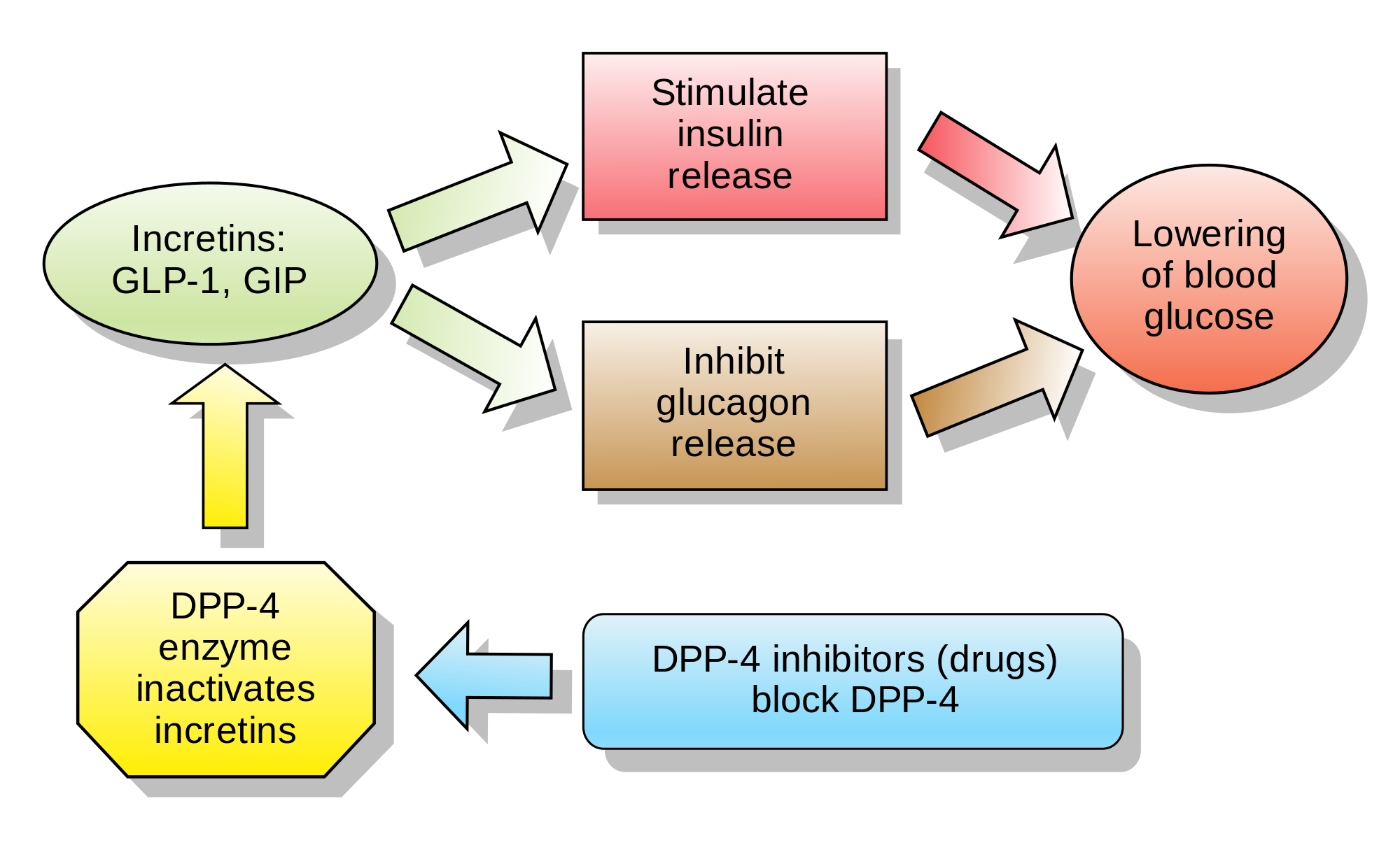

Inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4 inhibitors or gliptins) are a class of oral hypoglycemics that block the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). They can be used to treat diabetes mellitus type 2.

The first agent of the class—sitagliptin—was approved for marketing by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2006.[1]

Glucagon increases blood glucose levels, and DPP-4 inhibitors reduce glucagon and blood glucose levels. The mechanism of DPP-4 inhibitors is to increase incretin levels (GLP-1 and GIP),[2][3][4] which inhibit glucagon release, which in turn increases insulin secretion, decreases gastric emptying, and decreases blood glucose levels.

A 2018 meta-analysis found no favorable effect of DPP-4 inhibitors on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction or stroke in patients with type 2 diabetes.[5]

Examples

[edit]Drugs belonging to this class are:

- Sitagliptin[6] (FDA approved in 2006, and marketed by Merck & Co. as Januvia)

- Vildagliptin[7] (EU approved in 2007, and marketed in the EU by Novartis as Galvus)

- Saxagliptin (FDA approved in 2009, and marketed as Onglyza)

- Linagliptin (FDA approved in 2011, and marketed as Tradjenta by Eli Lilly and Company and Boehringer Ingelheim)[8]

- Gemigliptin (approved in Korea in 2012, and marketed by LG Life Sciences as Zemiglo, among other names)[9]

- Anagliptin (approved in Japan as Suiny in 2012; marketed by Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd. and Kowa Company, Ltd.)[10]

- Teneligliptin (approved in Japan as Tenelia in 2012)[11]

- Alogliptin (FDA approved in 2013 as Nesina/Vipidia, and marketed by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company)

- Trelagliptin (approved for use in Japan as Zafatek/Wedica in 2015)

- Omarigliptin (MK-3102; approved as Marizev in Japan in 2015,[12] having been developed by Merck & Co. In November 2015, Sheu and colleagues[13] showed that omarigliptin could be used once-weekly and was generally well tolerated throughout the base and extension studies)

- Evogliptin (approved as Suganon/Evodine for use in South Korea)[14]

- Gosogliptin (approved as Saterex for use in Russia)[15]

- Dutogliptin (PHX- 1149; free base[clarification needed] being developed by Phenomix Corporation. In a phase III trial as of April 2010)[16]

- Neogliptin[17]

- Retagliptin (SP-2086; approved in China)

- Denagliptin

- Cofrogliptin (HSK- 7653; compound 2)

- Fotagliptin

- Prusogliptin

- Cetagliptin (CGT 8012)

Berberine, an alkaloid found in plants of the genus Berberis (the "barberry"), inhibits DPP-4, which may at least partly explains the chemical's antihyperglycemic activity.[18]

Adverse effects

[edit]In individuals already taking sulphonylureas, use of DPP-4-class medications concurrently increases their risk for low blood sugar events relative to those on sulphonylureas alone.[19]

Adverse effects include nasopharyngitis, headache, nausea, heart failure, hypersensitivity, and skin reactions.[citation needed]

In late August 2015, the US FDA issued a warning that drugs like sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin, and other DPP-4 inhibitors could cause joint pain that can be severe and disabling.[20] However, studies assessing risk of rheumatoid arthritis among DPP-4 inhibitor users have been inconclusive.[21] A 2014 review found that the use of saxagliptin and alogliptin increased individuals' risk of developing heart failure, leading the FDA to add warnings to the labels of these drugs in 2016.[22] A 2018 meta-analysis indicated that the use of DPP-4 inhibitors was associated with a 58% increased risk of developing acute pancreatitis compared to placebo or no treatment.[23] Additionally, a 2018 observational study suggested an elevated risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease, specifically ulcerative colitis, which peaked after three to four years of use and decreased after more than four years.[24] Finally, a 2020 Cochrane systematic review found insufficient evidence to suggest that metformin monotherapy reduced all-cause mortality, serious adverse events, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, or end-stage renal disease when compared to DPP-4 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.[25]

Cancer

[edit]In response to a report of precancerous changes in the pancreases of rats and organ donors treated with the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin,[26][27] the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency each undertook independent reviews of all clinical and preclinical data related to the possible association of DPP-4 inhibitors with pancreatic cancer. In a joint letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, the agencies stated that they had not yet reached a final conclusion regarding a possible causative relationship.[28] A 2014 meta-analysis found no evidence for increased pancreatic cancer risk in people treated with DPP-4 inhibitors, but owing to the modest amount of data available, the authors were unable to completely exclude possibly increased risk.[29]

Combination drugs

[edit]Some DPP-4 inhibitor drugs have received approval from the FDA to be used with metformin concomitantly with additive effect to increase the level of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) which also decreases hepatic glucose production.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "FDA Approves New Treatment for Diabetes" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. October 17, 2006. Archived from the original on October 22, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-17.

- ^ McIntosh CH, Demuth HU, Pospisilik JA, Pederson R (June 2005). "Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: how do they work as new antidiabetic agents?". Regulatory Peptides. 128 (2): 159–65. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2004.06.001. PMID 15780435. S2CID 9151210.

- ^ Behme MT, Dupré J, McDonald TJ (April 2003). "Glucagon-like peptide 1 improved glycemic control in type 1 diabetes". BMC Endocrine Disorders. 3 (1) 3. doi:10.1186/1472-6823-3-3. PMC 154101. PMID 12697069.

- ^ Dupre J, Behme MT, Hramiak IM, McFarlane P, Williamson MP, Zabel P, McDonald TJ (June 1995). "Glucagon-like peptide I reduces postprandial glycemic excursions in IDDM". Diabetes. 44 (6): 626–30. doi:10.2337/diabetes.44.6.626. PMID 7789625.

- ^ Zheng SL, Roddick AJ, Aghar-Jaffar R, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis D, Oliver N, Meeran K (April 2018). "Association Between Use of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors, Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Agonists, and Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitors With All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 319 (15): 1580–1591. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3024. PMC 5933330. PMID 29677303.

- ^ Banting and Best Diabetes Centre at UT sitagliptin

- ^ Banting and Best Diabetes Centre at UT vildagliptin

- ^ "FDA approves new treatment for Type 2 diabetes". Fda.gov. 2011-05-02. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ^ "LG Life Science". Lgls.com. Archived from the original on 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- ^ "New Drugs Approved in FY 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-18. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- ^ Bronson J, Black A, Dhar TM, Ellsworth BA, Merritt JR (2012). Teneligliptin (Antidiabetic). To Market, To Market. Vol. 48. pp. 523–524. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-417150-3.00028-4. ISBN 978-0-12-417150-3.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Merck MARIZEV Once-Weekly DPP-4 Inhibitor For Type2 Diabetes Approved In Japan". NASDAQ. 28 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Sheu WH, Gantz I, Chen M, Suryawanshi S, Mirza A, Goldstein BJ, et al. (November 2015). "Safety and Efficacy of Omarigliptin (MK-3102), a Novel Once-Weekly DPP-4 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Patients With Type 2 Diabetes". Diabetes Care. 38 (11): 2106–14. doi:10.2337/dc15-0109. PMID 26310692.

- ^ "Dong-A ST's DPP4 inhibitor, SUGANON, got approved for type 2 diabetes in Korea". pipelinereview.com. October 2, 2015.

- ^ "SatRx LLC Announces First Registration in Russia of SatRx (gosogliptin), an Innovative Drug for Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes" (Press release). SatRx LLC.

- ^ "Forest Splits With Phenomix". San Diego Business Journal. 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2025-07-28.

- ^ Maslov IO, Zinevich TV, Kirichenko OG, Trukhan MV, Shorshnev SV, Tuaeva NO, Gureev MA, Dahlén AD, Porozov YB, Schiöth HB, Trukhan VM (February 2022). "Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Neogliptin, a Novel 2-Azabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-Based Inhibitor of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4)". Pharmaceuticals. 15 (3): 273. doi:10.3390/ph15030273. PMC 8949241. PMID 35337071.

- ^ Al-masri IM, Mohammad MK, Tahaa MO (October 2009). "Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) is one of the mechanisms explaining the hypoglycemic effect of berberine". Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 24 (5): 1061–6. doi:10.1080/14756360802610761. PMID 19640223. S2CID 25517996.

- ^ Salvo F, Moore N, Arnaud M, Robinson P, Raschi E, De Ponti F, et al. (May 2016). "Addition of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors to sulphonylureas and risk of hypoglycaemia: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 353 i2231. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2231. PMC 4854021. PMID 27142267.

- ^ "DPP-4 Inhibitors for Type 2 Diabetes: Drug Safety Communication - May Cause Severe Joint Pain". FDA. 2015-08-28. Archived from the original on September 1, 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Kathe N, Shah A, Said Q, Painter JT (February 2018). "DPP-4 Inhibitor-Induced Rheumatoid Arthritis Among Diabetics: A Nested Case-Control Study". Diabetes Therapy. 9 (1): 141–151. doi:10.1007/s13300-017-0353-5. PMC 5801239. PMID 29236221.

- ^ "Diabetes Meds Containing Saxagliptin and Alogliptin Linked to Increased HF". Pharmacy Practice News. April 2016.

- ^ Zheng SL, Roddick AJ, Aghar-Jaffar R, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis D, Oliver N, Meeran K (April 2018). "Association Between Use of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors, Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Agonists, and Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Inhibitors With All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 319 (15): 1580–1591. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3024. PMC 5933330. PMID 29677303.

- ^ Abrahami D, Douros A, Yin H, Yu OH, Renoux C, Bitton A, Azoulay L (March 2018). "Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among patients with type 2 diabetes: population based cohort study". BMJ. 360: k872. doi:10.1136/bmj.k872. PMC 5861502. PMID 29563098.

- ^ Gnesin F, Thuesen AC, Kähler LK, Madsbad S, Hemmingsen B, et al. (Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group) (June 2020). "Metformin monotherapy for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6) CD012906. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012906.pub2. PMC 7386876. PMID 32501595.

- ^ Matveyenko AV, Dry S, Cox HI, Moshtaghian A, Gurlo T, Galasso R, et al. (July 2009). "Beneficial endocrine but adverse exocrine effects of sitagliptin in the human islet amyloid polypeptide transgenic rat model of type 2 diabetes: interactions with metformin". Diabetes. 58 (7): 1604–15. doi:10.2337/db09-0058. PMC 2699878. PMID 19403868.

- ^ Butler AE, Campbell-Thompson M, Gurlo T, Dawson DW, Atkinson M, Butler PC (July 2013). "Marked expansion of exocrine and endocrine pancreas with incretin therapy in humans with increased exocrine pancreas dysplasia and the potential for glucagon-producing neuroendocrine tumors". Diabetes. 62 (7): 2595–604. doi:10.2337/db12-1686. PMC 3712065. PMID 23524641.

- ^ Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, de Graeff PA, Hummer BT, Bourcier T, Rosebraugh C (February 2014). "Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs--FDA and EMA assessment". The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (9): 794–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1314078. PMID 24571751.

- ^ Monami M, Dicembrini I, Mannucci E (January 2014). "Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and pancreatitis risk: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 16 (1): 48–56. doi:10.1111/dom.12176. PMID 23837679. S2CID 7642027.