Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tolbutamide

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2014) |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Orinase |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682481 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablet) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 96% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2C19-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 4.5 to 6.5 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.541 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

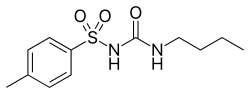

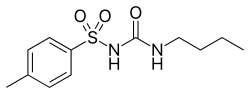

| Formula | C12H18N2O3S |

| Molar mass | 270.35 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 128.5 to 129.5 °C (263.3 to 265.1 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Tolbutamide is a first-generation potassium channel blocker, sulfonylurea oral hypoglycemic medication. This drug may be used in the management of type 2 diabetes if diet alone is not effective. Tolbutamide stimulates the secretion of insulin by the pancreas.

It is not routinely used due to a higher incidence of adverse effects compared to newer, second-generation sulfonylureas, such as Glibenclamide. It generally has a short duration of action due to its rapid metabolism, so is safe for use in older people.

It was discovered in 1956.[1]

Side effects

[edit]Side effects include:[medical citation needed]

- Hypoglycemia

- Weight gain

- Hypersensitivity: cross-allergicity with sulfonamides

- Drug interactions (especially first-generation drugs): Increased hypoglycemia with cimetidine, insulin, salicylates, and sulfonamides

Salicylates displace tolbutamide from its binding site on plasma binding proteins which lead to increase in free tolbutamide concentration, thus hypoglycemic shock.[2]

History

[edit]Orinase was developed by Upjohn Co. at a time when the primary medical treatment for diabetes was insulin injections. Eli Lilly had a lock on the market for insulin production at the time. The practical applicability of Orinase, like that of other treatments for disease states detected by paraclinical signs (such as lab test results) rather than clinically observable signs or patient-reported symptoms, benefited from increased sensitivity and availability of testing (in this instance, urinary glucose testing and later also fingerstick blood glucose testing). Milton Moskowitz (editor in 1961 of Drug and Cosmetic Industry) claimed that the introduction of Orinase, "expanded the total market by bringing under medical care diabetics who were formerly not treated."[3] It did this by changing the mindset about diabetes even more than insulin had. Treatment of this chronic disease was no longer seen as a mere slowing of "inexorable degeneration", but instead viewed through "a model of surveillance and early detection."[3]: 84

Orinase and other sulfonylureas emerged from European pharmaceutical research into antibiotics, specifically from attempts to develop sulfa compounds. One of the contenders for a new sulfa antibiotic had serious side effects during clinical trials at the University of Montpellier including blackouts, convulsions, and coma, side effects not observed with any other drugs in the sulfa cohort. An insulin researcher at the same university heard of these side effects and recognized them as common results of hypoglycemia. The resulting class of drugs for lowering blood sugar came to be known as the sulfonylureas, starting with Orinase and still in use today in other forms.

Unfortunately for diabetics dependent on insulin as a treatment for their condition, this research at Montpellier occurred in the early 1940s and was significantly disrupted by the German occupation of France during World War II. Development of these compounds was taken over by German pharmaceutical companies, which were obviously disinclined to share their bounty with nations upon which they were waging war. The German research was, in turn, disrupted by Germany's defeat in 1945 and the partition of Germany into East and West Germany. The sulfonylureas were trapped in East Germany. In 1952, someone smuggled a sample to a West German pharmaceutical company and research resumed. Clinical trials in diabetics began in 1954 in Berlin. In 1956, two different sulfonylureas were brought to market in Germany under the trade names Nadisan and Rastinon. American pharmaceutical companies in the postwar period had been seeking to establish business relations with the remnants of German pharmaceutical giants weakened by the war and partition of Germany. Upjohn (based in Kalamazoo until its purchase by Pharmacia in the 1990s) made deals with Hoechst, maker of Rastinon. The result was a cross-licensing agreement which produced Orinase.

Upjohn stood to open up a whole new arena of treatment for diabetes, one with a built-in and sustainable market, i.e. patient population. Just as two German companies brought sulfonylureas to market within the same year, Upjohn discovered Eli Lilly had begun clinical trials for carbutamide, another oral hypoglycemic. Upjohn pushed for large-scale clinical trials from 1955–1957, enrolling over 5,000 patients at multiple sites.

Upjohn's formulation was preferred when the Lilly formulation demonstrated evidence of toxicity in parallel trials at the Joslin Clinic. Lilly pulled carbutamide and halted development, leaving the field open for Upjohn to market its new treatment. In 1956, Upjohn filed for approval from the Food and Drug Administration. Jeremy A. Greene found the application's size – 10,580 pages in 23 volumes with 5,786 cases reports – was necessary to "render visible the relatively small improvements provided in less severe forms of diabetes." Indeed, Orinase was marketed by Upjohn not as a cure-all for all diabetics, but specifically as a treatment that was "not an oral insulin" and "did not work in all diabetics". Those were the instructions for marketing given to Upjohn's salespeople. As indicated by the FDA application, Orinase had been demonstrated "not to be effective in severe diabetes, but only in milder cases of the disease."[3]: 93 Orinase was one of a new class of drugs (including treatments for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia) aimed at providing marginal benefits over existing treatments for patients who had not previously been a target market for pharmaceuticals. As blood sugar testing for diagnosis of diabetes became more widespread, a curious side effect occurred: because blood sugar testing is not absolutely definitive in diagnoses of diabetes, more people were receiving borderline tests regarding their glycemic status. These borderline persons could be considered as being at risk for diabetes – prediabetic. Prediabetic patients have elevated blood sugar, but normal levels of sugar in their urine (glycosuria). Upjohn saw an opportunity to benefit and definitely market to a yet-greater expansion of the diabetic population, beyond even the "hidden diabetics" revealed by earlier public health campaigns. Upjohn also found a new use for Orinase: as a diagnostic. Orinase Diagnostic was added to the Orinase product line and, by 1962, was being sold as means of detecting prediabetes in that an abnormal response to Orinase following administration of cortisone in a "stress test" could be taken to indicate prediabetes. Orinase thus not only served to detect a previously hidden patient population, but also detected a patient population most likely to be interested in Orinase as a treatment for their newly diagnosed prediabetes. By the late 1960s, Orinase Diagnostic was withdrawn and the drug reverted to its therapeutic purpose. By that point, prediabetes had become a diagnosable and treatable condition which had dramatically increased the market for Orinase.

Orinase began to fall out of favor in May 1970 when asymptomatic prediabetics on long-term regimens of Orinase began to see news reports (beginning with the Washington Post) that Orinase may have serious side effects including death from cardiovascular problems, according to a long-term study. In many cases, patients learned of this before their physicians, and also before FDA could advise relabeling the medication or suggesting alterations in appropriate usage. The question of whether Orinase did or did not increase cardiovascular problems has not been conclusively settled. The result was that Orinase and other medical treatments for prediabetes were "rolled back" by the FDA and practitioners in an attempt to focus on symptomatic patients for whom the risks of treatment might be balanced by the symptoms of the disease.

Pharmacia and Upjohn (now merged) stopped making Orinase in 2000, though a generic is still available and occasionally used.

Historical consequences

[edit]The history of tolbutamide has had a lasting effect on medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. Patients today are still diagnosed with prediabetes, many of them managing to delay the onset of diabetes through dietary and lifestyle changes, but many also have the option to take metformin, which demonstrated a 31% reduction in three-year incidence of development of diabetes relative to placebo.[4] While impressive, the lifestyle-modification arm of that same trial demonstrated a 58% reduction.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Walker SR (2012). Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 978-94-009-2659-2.

- ^ Kalra S (2015). "Sulfonylureas and their use in clinical practice". Veterinary Record Open. 1 (1) e000080. Termedia Publishing. doi:10.1136/vetreco-2014-000080. PMC 4562452. PMID 26392882.

- ^ a b c Greene JA (2007). Prescribing by Numbers: Drugs and the Definition of Disease. Baltimore, MD.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8477-1.

- ^ Lawrence WL (24 February 1957). "Science in Review: Drug for the Treatment of Diabetes Tested And Found of Great Importance". The New York Times.

- ^ Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM (February 2002). "Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin". The New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (6): 393–403. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012512. PMC 1370926. PMID 11832527.