Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Liver

View on Wikipedia| Liver | |

|---|---|

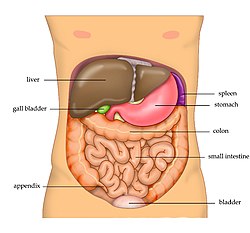

The human liver is located in the upper right abdomen | |

Location of human liver (in red) shown on a male body | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Foregut |

| System | Digestive system |

| Artery | Hepatic artery |

| Vein | Hepatic vein and hepatic portal vein |

| Nerve | Celiac ganglia and vagus nerve[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | jecur, iecur |

| Greek | hepar (ἧπαρ) root hepat- (ἡπατ-) |

| MeSH | D008099 |

| TA98 | A05.8.01.001 |

| TA2 | 3023 |

| FMA | 7197 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The liver is a major metabolic organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of various proteins and various other biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth.[2][3][4] In humans, it is located in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, below the diaphragm and mostly shielded by the lower right rib cage. Its other metabolic roles include carbohydrate metabolism, the production of a number of hormones, conversion and storage of nutrients such as glucose and glycogen, and the decomposition of red blood cells.[4] Anatomical and medical terminology often use the prefix hepat- from ἡπατο-, from the Greek word for liver, such as hepatology, and hepatitis.[5]

The liver is also an accessory digestive organ that produces bile, an alkaline fluid containing cholesterol and bile acids, which emulsifies and aids the breakdown of dietary fat. The gallbladder, a small hollow pouch that sits just under the right lobe of liver, stores and concentrates the bile produced by the liver, which is later excreted to the duodenum to help with digestion.[6] The liver's highly specialized tissue, consisting mostly of hepatocytes, regulates a wide variety of high-volume biochemical reactions, including the synthesis and breakdown of small and complex organic molecules, many of which are necessary for normal vital functions.[7] Estimates regarding the organ's total number of functions vary, but is generally cited as being around 500.[8] For this reason, the liver has sometimes been described as the body's chemical factory.[9][10]

It is not known how to compensate for the absence of liver function in the long term, although liver dialysis techniques can be used in the short term. Artificial livers have not been developed to promote long-term replacement in the absence of the liver. As of 2018[update], liver transplantation is the only option for complete liver failure.[11]

Structure

[edit]

The liver is a dark reddish brown, wedge-shaped organ with two lobes of unequal size and shape. A human liver normally weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms (3.3 pounds)[12] and has a width of about 15 centimetres (6 inches).[13] There is considerable size variation between individuals, with the standard reference range for men being 970–1,860 grams (2.14–4.10 lb)[14] and for women 600–1,770 g (1.32–3.90 lb).[15] It is both the heaviest internal organ and the largest gland in the human body. It is located in the right upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity, resting just below the diaphragm, to the right of the stomach, and overlying the gallbladder.[6]

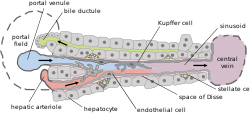

The liver is connected to two large blood vessels: the hepatic artery and the portal vein. The hepatic artery carries oxygen-rich blood from the aorta via the celiac trunk, whereas the portal vein carries blood rich in digested nutrients from the entire gastrointestinal tract and also from the spleen and pancreas.[11] These blood vessels subdivide into small capillaries known as liver sinusoids, which then lead to hepatic lobules.

Hepatic lobules are the functional units of the liver. Each lobule is made up of millions of hepatocytes, which are the basic metabolic cells. The lobules are held together by a fine, dense, irregular, fibroelastic connective tissue layer extending from the fibrous capsule covering the entire liver known as Glisson's capsule after British doctor Francis Glisson.[4] This tissue extends into the structure of the liver by accompanying the blood vessels, ducts, and nerves at the hepatic hilum. The whole surface of the liver, except for the bare area, is covered in a serous coat derived from the peritoneum, and this firmly adheres to the inner Glisson's capsule.

Gross anatomy

[edit]Lobes

[edit]

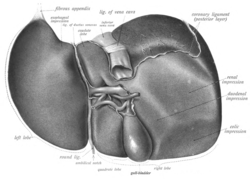

The liver is grossly divided into two parts when viewed from above – a right and a left lobe – and four parts when viewed from below (left, right, caudate, and quadrate lobes).[16]

The falciform ligament makes a superficial division of the liver into a left and right lobe. From below, the two additional lobes are located between the right and left lobes, one in front of the other. A line can be imagined running from the left of the vena cava and all the way forward to divide the liver and gallbladder into two halves.[17] This line is called Cantlie's line.[18]

Other anatomical landmarks include the ligamentum venosum and the round ligament of the liver, which further divide the left side of the liver in two sections. An important anatomical landmark, the porta hepatis, divides this left portion into four segments, which can be numbered starting at the caudate lobe as I in an anticlockwise manner. From this parietal view, seven segments can be seen, because the eighth segment is only visible in the visceral view.[19]

Surfaces

[edit]

On the diaphragmatic surface, apart from a triangular bare area where it connects to the diaphragm, the liver is covered by a thin, double-layered membrane, the peritoneum, that helps to reduce friction against other organs.[20] This surface covers the convex shape of the two lobes where it accommodates the shape of the diaphragm. The peritoneum folds back on itself to form the falciform ligament and the right and left triangular ligaments.[21]

These peritoneal ligaments are not related to the anatomic ligaments in joints, and the right and left triangular ligaments have no known functional importance, though they serve as surface landmarks.[21] The falciform ligament functions to attach the liver to the posterior portion of the anterior body wall.

The visceral surface or inferior surface is uneven and concave. It is covered in peritoneum apart from where it attaches the gallbladder and the porta hepatis.[20] The fossa of gallbladder lies to the right of the quadrate lobe, occupied by the gallbladder with its cystic duct close to the right end of porta hepatis.

Impressions

[edit]

Several impressions on the surface of the liver accommodate the various adjacent structures and organs. Underneath the right lobe and to the right of the gallbladder fossa are two impressions, one behind the other and separated by a ridge. The one in front is a shallow colic impression, formed by the hepatic flexure and the one behind is a deeper renal impression accommodating part of the right kidney and part of the suprarenal gland.[22]

The suprarenal impression is a small, triangular, depressed area on the liver. It is located close to the right of the fossa, between the bare area and the caudate lobe, and immediately above the renal impression. The greater part of the suprarenal impression is devoid of peritoneum and it lodges the right suprarenal gland.[23]

Medial to the renal impression is a third and slightly marked impression, lying between it and the neck of the gall bladder. This is caused by the descending portion of the duodenum, and is known as the duodenal impression.[23]

The inferior surface of the left lobe of the liver presents behind and to the left of the gastric impression.[23] This is moulded over the upper front surface of the stomach, and to the right of this is a rounded eminence, the tuber omentale, which fits into the concavity of the lesser curvature of the stomach and lies in front of the anterior layer of the lesser omentum.

Microscopic anatomy

[edit]

Microscopically, each liver lobe is seen to be made up of hepatic lobules. The lobules are roughly hexagonal, and consist of plates of hepatocytes, and sinusoids radiating from a central vein towards an imaginary perimeter of interlobular portal triads.[24] The central vein joins to the hepatic vein to carry blood out from the liver. A distinctive component of a lobule is the portal triad, which can be found running along each of the lobule's corners. The portal triad consists of the hepatic artery, the portal vein, and the common bile duct.[25] The triad may be seen on a liver ultrasound, as a Mickey Mouse sign with the portal vein as the head, and the hepatic artery, and the common bile duct as the ears.[26]

Histology, the study of microscopic anatomy, shows two major types of liver cell: parenchymal cells and nonparenchymal cells. About 70–85% of the liver volume is occupied by parenchymal hepatocytes. Nonparenchymal cells constitute 40% of the total number of liver cells but only 6.5% of its volume.[27] The liver sinusoids are lined with two types of cell, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and phagocytic Kupffer cells.[28] Hepatic stellate cells are nonparenchymal cells found in the perisinusoidal space, between a sinusoid and a hepatocyte.[27] Additionally, intrahepatic lymphocytes are often present in the sinusoidal lumen.[27]

-

Microscopic anatomy of the liver

-

Types of capillaries–sinusoid on right

-

3D medical animation still shot depicting parts of liver

Functional anatomy

[edit]

The central area, or hepatic hilum, includes the opening known as the porta hepatis which carries the common bile duct and common hepatic artery, and the opening for the portal vein. The duct, vein, and artery divide into left and right branches, and the areas of the liver supplied by these branches constitute the functional left and right lobes. The functional lobes are separated by the imaginary plane, Cantlie's line, joining the gallbladder fossa to the inferior vena cava. The plane separates the liver into the true right and left lobes. The middle hepatic vein also demarcates the true right and left lobes. The right lobe is further divided into an anterior and posterior segment by the right hepatic vein. The left lobe is divided into the medial and lateral segments by the left hepatic vein.

The hilum of the liver is described in terms of three plates that contain the bile ducts and blood vessels. The contents of the whole plate system are surrounded by a sheath.[29] The three plates are the hilar plate, the cystic plate and the umbilical plate and the plate system is the site of the many anatomical variations to be found in the liver.[29]

Couinaud classification system

[edit]

In the widely used Couinaud system, the functional lobes are further divided into a total of eight subsegments based on a transverse plane through the bifurcation of the main portal vein.[30] The caudate lobe is a separate structure that receives blood flow from both the right- and left-sided vascular branches.[31][32] The Couinaud classification divides the liver into eight functionally independent liver segments. Each segment has its own vascular inflow, outflow and biliary drainage. In the centre of each segment are branches of the portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct. In the periphery of each segment is vascular outflow through the hepatic veins.[33] The classification system uses the vascular supply in the liver to separate the functional units (numbered I to VIII) with unit 1, the caudate lobe, receiving its supply from both the right and the left branches of the portal vein. It contains one or more hepatic veins which drain directly into the inferior vena cava.[30] The remainder of the units (II to VIII) are numbered in a clockwise fashion:[33]

Gene and protein expression

[edit]About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and 60% of these genes are expressed in a normal, adult liver.[34][35] Over 400 genes are more specifically expressed in the liver, with some 150 genes highly specific for liver tissue. A large fraction of the corresponding liver-specific proteins are mainly expressed in hepatocytes and secreted into the blood and constitute plasma proteins and hepatokines. Other liver-specific proteins are certain liver enzymes such as HAO1 and RDH16, proteins involved in bile synthesis such as BAAT and SLC27A5, and transporter proteins involved in the metabolism of drugs, such as ABCB11 and SLC2A2. Examples of highly liver-specific proteins include apolipoprotein A II, coagulation factors F2 and F9, complement factor related proteins, and the fibrinogen beta chain protein.[36]

Development

[edit]

Organogenesis, the development of the organs, takes place from the third to the eighth week during embryonic development. The origins of the liver lie in both the ventral portion of the foregut endoderm (endoderm being one of the three embryonic germ layers) and the constituents of the adjacent septum transversum mesenchyme. In the human embryo, the hepatic diverticulum is the tube of endoderm that extends out from the foregut into the surrounding mesenchyme. The mesenchyme of septum transversum induces this endoderm to proliferate, to branch, and to form the glandular epithelium of the liver. A portion of the hepatic diverticulum (that region closest to the digestive tube) continues to function as the drainage duct of the liver, and a branch from this duct produces the gallbladder.[37] Besides signals from the septum transversum mesenchyme, fibroblast growth factor from the developing heart also contributes to hepatic competence, along with retinoic acid emanating from the lateral plate mesoderm. The hepatic endodermal cells undergo a morphological transition from columnar to pseudostratified resulting in thickening into the early liver bud. Their expansion forms a population of the bipotential hepatoblasts.[38] Hepatic stellate cells are derived from mesenchyme.[39]

After migration of hepatoblasts into the septum transversum mesenchyme, the hepatic architecture begins to be established, with liver sinusoids and bile canaliculi appearing. The liver bud separates into the lobes. The left umbilical vein becomes the ductus venosus and the right vitelline vein becomes the portal vein. The expanding liver bud is colonized by hematopoietic cells. The bipotential hepatoblasts begin differentiating into biliary epithelial cells and hepatocytes. The biliary epithelial cells differentiate from hepatoblasts around portal veins, first producing a monolayer, and then a bilayer of cuboidal cells. In ductal plate, focal dilations emerge at points in the bilayer, become surrounded by portal mesenchyme, and undergo tubulogenesis into intrahepatic bile ducts. Hepatoblasts not adjacent to portal veins instead differentiate into hepatocytes and arrange into cords lined by sinusoidal epithelial cells and bile canaliculi. Once hepatoblasts are specified into hepatocytes and undergo further expansion, they begin acquiring the functions of a mature hepatocyte, and eventually mature hepatocytes appear as highly polarized epithelial cells with abundant glycogen accumulation. In the adult liver, hepatocytes are not equivalent, with position along the portocentrovenular axis within a liver lobule dictating expression of metabolic genes involved in drug metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, ammonia detoxification, and bile production and secretion. WNT/β-catenin has now been identified to be playing a key role in this phenomenon.[38]

At birth, the liver comprises roughly 4% of body weight and weighs on average about 120 g (4 oz). Over the course of further development, it will increase to 1.4–1.6 kg (3.1–3.5 lb) but will only take up 2.5–3.5% of body weight.[40]

Hepatosomatic index (HSI) is the ratio of liver weight to body weight.[41]

Fetal blood supply

[edit]In the growing fetus, a major source of blood to the liver is the umbilical vein, which supplies nutrients to the growing fetus. The umbilical vein enters the abdomen at the umbilicus and passes upward along the free margin of the falciform ligament of the liver to the inferior surface of the liver. There, it joins with the left branch of the portal vein. The ductus venosus carries blood from the left portal vein to the left hepatic vein and then to the inferior vena cava, allowing placental blood to bypass the liver. In the fetus, the liver does not perform the normal digestive processes and filtration of the infant liver because nutrients are received directly from the mother via the placenta. The fetal liver releases some blood stem cells that migrate to the fetal thymus, creating the T cells (or T lymphocytes). After birth, the formation of blood stem cells shifts to the red bone marrow. After 2–5 days, the umbilical vein and ductus venosus are obliterated; the former becomes the round ligament of liver and the latter becomes the ligamentum venosum. In the disorders of cirrhosis and portal hypertension, the umbilical vein can open up again.

Unlike eutherian mammals, in marsupials the liver remains haematopoietic well after birth.[42][43][44][45]

Functions

[edit]The various functions of the liver are carried out by the liver cells or hepatocytes. The liver is thought to be responsible for up to 500 separate functions, usually in combination with other systems and organs. Currently, no artificial organ or device is capable of reproducing all the functions of the liver. Some functions can be carried out by liver dialysis, an experimental treatment for liver failure. The liver also accounts for about 20% of resting total body oxygen consumption.

Blood supply

[edit]The liver gets its blood supply from the hepatic portal vein and hepatic arteries. The hepatic portal vein delivers around 75% of the liver's blood supply and carries venous blood drained from the spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and its associated organs. The hepatic arteries supply arterial blood to the liver, accounting for the remaining quarter of its blood flow. Oxygen is provided from both sources; about half of the liver's oxygen demand is met by the hepatic portal vein, and half is met by the hepatic arteries.[46] The hepatic artery also has both alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors; therefore, flow through the artery is controlled, in part, by the splanchnic nerves of the autonomic nervous system.

Blood flows through the liver sinusoids and empties into the central vein of each lobule. The central veins coalesce into hepatic veins, which leave the liver and drain into the inferior vena cava.[47]

Biliary flow

[edit]

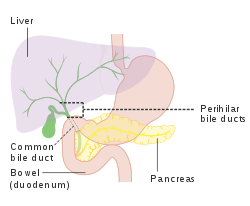

The biliary tract is derived from the branches of the bile ducts. The biliary tract, also known as the biliary tree, is the path by which bile is secreted by the liver then transported to the first part of the small intestine, the duodenum. The bile produced in the liver is collected in bile canaliculi, small grooves between the faces of adjacent hepatocytes. The canaliculi radiate to the edge of the liver lobule, where they merge to form bile ducts. Within the liver, these ducts are termed intrahepatic bile ducts, and once they exit the liver, they are considered extrahepatic. The intrahepatic ducts eventually drain into the right and left hepatic ducts, which exit the liver at the transverse fissure, and merge to form the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct from the gallbladder joins with the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct.[47] The biliary system and connective tissue is supplied by the hepatic artery alone.

Bile either drains directly into the duodenum via the common bile duct, or is temporarily stored in the gallbladder via the cystic duct. The common bile duct and the pancreatic duct enter the second part of the duodenum together at the hepatopancreatic ampulla, also known as the ampulla of Vater.

Metabolism

[edit]The liver plays a major role in carbohydrate, protein, amino acid, and lipid metabolism.

Carbohydrate metabolism

[edit]The liver performs several roles in carbohydrate metabolism.

- The liver synthesizes and stores around 100g of glycogen via glycogenesis, the formation of glycogen from glucose.

- When needed, the liver releases glucose into the blood by performing glycogenolysis, the breakdown of glycogen into glucose.[48]

- The liver is also responsible for gluconeogenesis, which is the synthesis of glucose from certain amino acids, lactate, or glycerol. Adipose and liver cells produce glycerol by breakdown of fat, which the liver uses for gluconeogenesis.[48]

- Liver also does glyconeogenesis which is synthesis of glycogen from lactic acid.[49]

Protein metabolism

[edit]The liver is responsible for the mainstay of protein metabolism, synthesis as well as degradation. All plasma proteins except Gamma-globulins are synthesised in the liver.[50] It is also responsible for a large part of amino acid synthesis. The liver plays a role in the production of clotting factors, as well as red blood cell production. Some of the proteins synthesized by the liver include coagulation factors I (fibrinogen), II (prothrombin), V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, as well as protein C, protein S and antithrombin. The liver is a major site of production for thrombopoietin, a glycoprotein hormone that regulates the production of platelets by the bone marrow.[51]

Lipid metabolism

[edit]The liver plays several roles in lipid metabolism: it performs cholesterol synthesis, lipogenesis, and the production of triglycerides, and a bulk of the body's lipoproteins are synthesized in the liver. The liver plays a key role in digestion, as it produces and excretes bile (a yellowish liquid) required for emulsifying fats and help the absorption of vitamin K from the diet. Some of the bile drains directly into the duodenum, and some is stored in the gallbladder. The liver produces insulin-like growth factor 1, a polypeptide protein hormone that plays an important role in childhood growth and continues to have anabolic effects in adults.

Breakdown

[edit]The liver is responsible for the breakdown of insulin and other hormones. The liver breaks down bilirubin via glucuronidation, facilitating its excretion into bile. The liver is responsible for the breakdown and excretion of many waste products. It plays a key role in breaking down or modifying toxic substances (e.g., methylation) and most medicinal products in a process called drug metabolism. This sometimes results in toxication, when the metabolite is more toxic than its precursor. Preferably, the toxins are conjugated to avail excretion in bile or urine. The liver converts ammonia into urea as part of the ornithine cycle or the urea cycle, and the urea is excreted in the urine.[52]

Blood reservoir

[edit]Because the liver is an expandable organ, large quantities of blood can be stored in its blood vessels. Its normal blood volume, including both that in the hepatic veins and that in the hepatic sinuses, is about 450 milliliters, or almost 10 percent of the body's total blood volume. When high pressure in the right atrium causes backpressure in the liver, the liver expands, and 0.5 to 1 liter of extra blood is occasionally stored in the hepatic veins and sinuses. This occurs especially in cardiac failure with peripheral congestion. Thus, in effect, the liver is a large, expandable, venous organ capable of acting as a valuable blood reservoir in times of excess blood volume and capable of supplying extra blood in times of diminished blood volume.[53]

Lymph production

[edit]Because the pores in the hepatic sinusoids are very permeable and allow ready passage of both fluid and proteins into the perisinusoidal space, the lymph draining from the liver usually has a protein concentration of about 6 g/dl, which is only slightly less than the protein concentration of plasma. Also, the high permeability of the liver sinusoid epithelium allows large quantities of lymph to form. Therefore, about half of all the lymph formed in the body under resting conditions arises in the liver.

Other

[edit]- The liver stores a multitude of substances, including vitamin A (1–2 years' supply), vitamin D (1–4 months' supply),[54] vitamin B12 (3–5 years' supply),[55] vitamin K, vitamin E, iron, copper, zinc, cobalt, molybdenum, etc.

- Haemopoiesis - The formation of blood cells is called haemopoiesis. In the embryonic stage, RBCs and WBCs are formed by liver. In the first trimester fetus, the liver is the main site of red blood cell production. By the 32nd week of gestation, the bone marrow has almost completely taken over that task.[56]

- The liver helps in the purification of blood. The Kupffer cells of liver are phagocytic cells that help in the phagocytosis of dead blood cells and bacteria from the blood.[57]

- The liver is responsible for immunological effects – the mononuclear phagocyte system of the liver contains many immunologically active cells, acting as a 'sieve' for antigens carried to it via the portal system.

- The liver produces albumin, the most abundant protein in blood serum. Albumin is essential in the maintenance of oncotic pressure and acts as a transport for fatty acids and steroid hormones.

- The liver synthesizes angiotensinogen, a hormone that is responsible for raising the blood pressure when activated by renin, an enzyme that is released when the kidney senses low blood pressure.

- The liver produces the enzyme catalase to break down hydrogen peroxide, a toxic oxidising agent, into water and oxygen.

Clinical significance

[edit]Disease

[edit]

The liver is a vital organ and supports almost every other organ in the body. Severe or end-stage liver failure has dire consequences for the body's overall health and quality of life. Visible signs of liver disease include jaundice and ascites. Hepatomegaly refers to an enlarged liver and may be caused by several underlying diseases. It can be palpated in an abdominal exam.

Scarring (fibrosis) of the liver from any cause can lead to cirrhosis. Cirrhosis increases the resistance to blood flow in the liver, and can result in portal hypertension. Congested anastomoses between the portal venous system and the systemic circulation, can be a subsequent condition.

The most common chronic liver disease is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which affects an estimated one-third of the world population.[58]

Hepatitis is a common condition of inflammation of the liver. The cause is usually viral, and the most common of these infections are hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Some of these infections are transmitted sexually or through non-sterile needles. Inflammation can also be caused by other viruses in the family Herpesviridae such as the herpes simplex virus. Chronic (rather than acute) infection with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus is the main cause of liver cancer.[59] Globally, about 248 million individuals are chronically infected with hepatitis B (with 843,724 in the U.S.),[60] and 142 million are chronically infected with hepatitis C[61] (with 2.7 million in the U.S.).[62] Globally there are about 114 million and 20 million cases of hepatitis A[61] and hepatitis E[63] respectively, but these generally resolve and do not become chronic. Hepatitis D virus is a "satellite" of hepatitis B virus (it can only infect in the presence of hepatitis B), and co-infects nearly 20 million people with hepatitis B, globally.[64]

Hepatic encephalopathy is caused by an accumulation of toxins in the bloodstream that are normally removed by the liver. This condition can result in coma and or death if not treated.

Budd–Chiari syndrome is a condition caused by blockage of the hepatic veins (including thrombosis) that drain the liver. It presents with the classical triad of abdominal pain, ascites and liver enlargement.[65]

Many diseases of the liver are accompanied by jaundice caused by increased levels of bilirubin in the system. The bilirubin results from the breakup of the hemoglobin of dead red blood cells; normally, the liver removes bilirubin from the blood and excretes it through bile.

Other disorders caused by excessive alcohol consumption are grouped under alcoholic liver diseases and these include alcoholic hepatitis, fatty liver, and cirrhosis. Factors contributing to the development of alcoholic liver diseases are not only the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, but can also include gender, genetics, and liver insult.

Liver damage can also be caused by drugs, particularly paracetamol and drugs used to treat cancer.

A rupture of the liver can be caused by a liver shot used in combat sports.

Primary biliary cholangitis is an autoimmune disease of the liver.[66][67] It is marked by slow progressive destruction of the small bile ducts of the liver, with the intralobular ducts (Canals of Hering) affected early in the disease.[68] When these ducts are damaged, bile and other toxins build up in the liver (cholestasis) and over time damages the liver tissue in combination with ongoing immune related damage.

There are also many pediatric liver diseases, including biliary atresia, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, alagille syndrome, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis and hepatic hemangioma a benign tumour the most common type of liver tumour, thought to be congenital. A genetic disorder causing multiple cysts to form in the liver tissue, usually in later life, and usually asymptomatic, is polycystic liver disease. Diseases that interfere with liver function will lead to derangement of these processes. However, the liver has a great capacity to regenerate and has a large reserve capacity. In most cases, the liver only produces symptoms after extensive damage.

The bare area of the liver is a site that is vulnerable to the passing of infection from the abdominal cavity to the thoracic cavity.

Consuming caffeine regularly may help safeguard individuals from liver cirrhosis.[69] Additionally, it has been shown to slow the advancement of liver disease in those already affected, lower the risk of liver fibrosis, and provide a protective benefit against liver cancer for moderate coffee drinkers. A 2017 study revealed that the positive effects of caffeine on the liver were evident regardless of the coffee preparation method.[70]

Symptoms

[edit]The classic symptoms of liver damage include the following:

- Pale stools occur when stercobilin, a brown pigment, is absent from the stool. Stercobilin is derived from bilirubin metabolites produced in the liver.

- Dark urine occurs when bilirubin mixes with urine

- Jaundice (yellow skin and/or whites of the eyes) This is where bilirubin deposits in skin, causing an intense itch. Itching is the most common complaint by people who have liver failure. Often this itch cannot be relieved by drugs.

- Fluid accumulating in the abdomen, and swelling of the ankles and feet occurs because the liver fails to make albumin.

- Excessive fatigue occurs from a generalized loss of nutrients, minerals and vitamins.

- Bruising and easy bleeding are other features of liver disease. The liver makes clotting factors, substances which help prevent bleeding. When liver damage occurs, these factors are no longer present and severe bleeding can occur.[71]

- Pain in the upper right quadrant can result from the stretching of Glisson's capsule in conditions of hepatitis and pre-eclampsia.

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of liver disease is made by liver function tests, groups of blood tests, that can readily show the extent of liver damage. If infection is suspected, then other serological tests will be carried out. A physical examination of the liver can only reveal its size and any tenderness, and some form of imaging such as an ultrasound or CT scan may also be needed.

Sometimes a liver biopsy will be necessary, and a tissue sample is taken through a needle inserted into the skin just below the rib cage. This procedure may be helped by a sonographer providing ultrasound guidance to an interventional radiologist.[72]

-

Axial CT image showing anomalous hepatic veins coursing on the liver's subcapsular anterior surface[73]

-

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) CT image as viewed anteriorly showing the anomalous hepatic veins coursing on the anterior surface of the liver

-

Lateral MIP view in the same patient as previous image

-

A CT scan in which the liver and portal vein are shown

Liver regeneration

[edit]The liver is the only human internal organ capable of natural regeneration of lost tissue; as little as 25% of a liver can regenerate into a whole liver.[74] This is, however, not true regeneration but rather compensatory growth in mammals.[75] The lobes that are removed do not regrow and the growth of the liver is a restoration of function, not original form. This contrasts with true regeneration where both original function and form are restored. In some other species, such as zebrafish, the liver undergoes true regeneration by restoring both shape and size of the organ.[76] In the liver, large areas of the tissues are formed but for the formation of new cells there must be sufficient amount of material so the circulation of the blood becomes more active.[77]

This is predominantly due to the hepatocytes re-entering the cell cycle. That is, the hepatocytes go from the quiescent G0 phase to the G1 phase and undergo mitosis. This process is activated by the p75 receptors.[78] There is also some evidence of bipotential stem cells, called hepatic oval cells or ovalocytes (not to be confused with oval red blood cells of ovalocytosis), which are thought to reside in the canals of Hering. These cells can differentiate into either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. Cholangiocytes are the epithelial lining cells of the bile ducts.[79] They are cuboidal epithelium in the small interlobular bile ducts, but become columnar and mucus secreting in larger bile ducts approaching the porta hepatis and the extrahepatic ducts. Research is being carried out on the use of stem cells for the generation of an artificial liver.

Scientific and medical works about liver regeneration often refer to the Greek Titan Prometheus who was chained to a rock in the Caucasus where, each day, his liver was devoured by an eagle, only to grow back each night. The myth suggests the ancient Greeks may have known about the liver's remarkable capacity for self-repair.[80]

Liver transplantation

[edit]Human liver transplants were first performed by Thomas Starzl in the United States and Roy Calne in Cambridge, England in 1963 and 1967, respectively.

Liver transplantation is the only option for those with irreversible liver failure. Most transplants are done for chronic liver diseases leading to cirrhosis, such as chronic hepatitis C, alcoholism, and autoimmune hepatitis. Less commonly, liver transplantation is done for fulminant hepatic failure, in which liver failure occurs rapidly over a period of days or weeks.

Liver allografts for transplant usually come from donors who have died from fatal brain injury. Living donor liver transplantation is a technique in which a portion of a living person's liver is removed (hepatectomy) and used to replace the entire liver of the recipient. This was first performed in 1989 for pediatric liver transplantation. Only 20 percent of an adult's liver (Couinaud segments 2 and 3) is needed to serve as a liver allograft for an infant or small child.

More recently,[when?] adult-to-adult liver transplantation has been done using the donor's right hepatic lobe, which amounts to 60 percent of the liver. Due to the ability of the liver to regenerate, both the donor and recipient end up with normal liver function if all goes well. This procedure is more controversial, as it entails performing a much larger operation on the donor, and indeed there were at least two donor deaths out of the first several hundred cases. A 2006 publication addressed the problem of donor mortality and found at least fourteen cases.[81] The risk of postoperative complications (and death) is far greater in right-sided operations than that in left-sided operations.

With the recent advances of noninvasive imaging, living liver donors usually have to undergo imaging examinations for liver anatomy to decide if the anatomy is feasible for donation. The evaluation is usually performed by multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MDCT is good in vascular anatomy and volumetry. MRI is used for biliary tree anatomy. Donors with very unusual vascular anatomy, which makes them unsuitable for donation, could be screened out to avoid unnecessary operations.

-

MDCT image. Arterial anatomy contraindicated for liver donation

-

MDCT image. Portal venous anatomy contraindicated for liver donation

-

MDCT image. 3D image created by MDCT can clearly visualize the liver, measure the liver volume, and plan the dissection plane to facilitate the liver transplantation procedure.

-

Phase contrast CT image. Contrast is perfusing the right liver but not the left due to a left portal vein thrombus.

Society and culture

[edit]Some cultures regard the liver as the seat of the soul.[82] In Greek mythology, the gods punished Prometheus for revealing fire to humans by chaining him to a rock where a vulture (or an eagle) would peck out his liver, which would regenerate overnight (the liver is the only human internal organ that actually can regenerate itself to a significant extent). Many ancient peoples of the Near East and Mediterranean areas practiced a type of divination called haruspicy or hepatomancy, where they tried to obtain information by examining the livers of sheep and other animals.

In Plato, and in later physiology, the liver was thought to be the seat of the darkest emotions (specifically wrath, jealousy and greed) which drive men to action.[83] The Talmud (tractate Berakhot 61b) refers to the liver as the seat of anger, with the gallbladder counteracting this. The Persian, Urdu, and Hindi languages (جگر or जिगर or jigar) refer to the liver in figurative speech to indicate courage and strong feelings, or "their best"; e.g., "This Mecca has thrown to you the pieces of its liver!".[84] The term jan e jigar, literally "the strength (power) of my liver", is a term of endearment in Urdu. In Persian slang, jigar is used as an adjective for any object which is desirable, especially women. In the Zulu language, the word for liver (isibindi) is the same as the word for courage. In English the term 'lily-livered' is used to indicate cowardice from the medieval belief that the liver was the seat of courage. Spanish hígados also means "courage".[85] However the secondary meaning of Basque gibel is "indolence".[86]

In biblical Hebrew, the word for liver, כבד (Kauved, stemmed KBD or KVD, similar to Arabic الكبد), also means heavy and is used to describe the rich ("heavy" with possessions) and honor (presumably for the same reason). In the Book of Lamentations (2:11) it is used to describe the physiological responses to sadness by "my liver spilled to earth" along with the flow of tears and the overturning in bitterness of the intestines.[87] On several occasions in the book of Psalms (most notably 16:9), the word is used to describe happiness in the liver, along with the heart (which beats rapidly) and the flesh (which appears red under the skin). Further usage as the self (similar to "your honor") is widely available throughout the old testament, sometimes compared to the breathing soul (Genesis 49:6, Psalms 7:6, etc.). An honorable hat was also referred to with this word (Job 19:9, etc.) and under that definition appears many times along with פאר Pe'er - grandeur.[88] These four meanings were used in preceding ancient Afro-Asiatic languages such as Akkadian and Ancient Egyptian preserved in classical Ethiopic Ge'ez language.[89]

Anatomical and medical terminology often use the prefix hepat- from ἡπατο-, from the Greek word for liver, such as hepatology, and hepatitis[5]

Food

[edit]

Humans commonly eat the livers of mammals, fowl, and fish as food. Domestic pig, ox, lamb, calf, chicken, and goose livers are widely available from butchers and supermarkets. In the Romance languages, the anatomical word for "liver" (French foie, Spanish hígado, etc.) derives not from the Latin anatomical term, jecur, but from the culinary term ficatum, literally "stuffed with figs", referring to the livers of geese that had been fattened on figs.[90] Animal livers are rich in iron, vitamin A and vitamin B12; and cod liver oil is commonly used as a dietary supplement.

Liver can be baked, boiled, broiled, fried, stir-fried, or eaten raw (asbeh nayeh or sawda naye in Lebanese cuisine, or liver sashimi in Japanese cuisine). In many preparations, pieces of liver are combined with pieces of meat or kidneys, as in the various forms of Middle Eastern mixed grill (e.g. meurav Yerushalmi). Well-known examples include liver pâté, foie gras, chopped liver, and leverpastej. Liver sausages, such as Braunschweiger and liverwurst, are also a valued meal. Liver sausages may also be used as spreads. A traditional South African delicacy, skilpadjies, is made of minced lamb's liver wrapped in netvet (caul fat), and grilled over an open fire. Traditionally, some fish livers were valued as food, especially the stingray liver. It was used to prepare delicacies, such as poached skate liver on toast in England, as well as the beignets de foie de raie and foie de raie en croute in French cuisine.[91]

Giraffe liver

[edit]

The Humr are one of the tribes in the Baggara ethnic group, native to southwestern Kordofan in Sudan who speak Shuwa (Chadian Arabic), make a non-alcoholic drink from the liver and bone marrow of the giraffe, which they call umm nyolokh. They claim it is intoxicating (Arabic سكران sakran), causing dreams and even waking hallucinations.[92] Anthropologist Ian Cunnison accompanied the Humr on one of their giraffe-hunting expeditions in the late 1950s, and noted that:

- It is said that a person, once he has drunk umm nyolokh, will return to giraffe again and again. Humr, being Mahdists, are strict abstainers [from alcohol] and a Humrawi is never drunk (sakran) on liquor or beer. But he uses this word to describe the effects which umm nyolokh has upon him.[93]

Cunnison's remarkable account of an apparently psychoactive mammal found its way from a somewhat obscure scientific paper into more mainstream literature through a conversation between W. James of the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Oxford and specialist on the use of hallucinogens and intoxicants in society, and R. Rudgley, who discussed it in a book on psychoactive drugs for general readers.[92] He speculated that a hallucinogenic compound N,N-Dimethyltryptamine in the giraffe liver might account for the intoxicating properties claimed for umm nyolokh.[92]

Cunnison, on the other hand, writing in 1958 found it hard to believe in the literal truth of the Humr's assertion that the drink was intoxicating:

- I can only assume that there is no intoxicating substance in the drink, and that the effect it produces is simply a matter of convention, although it may be brought about subconsciously.[93]

The study of entheogens in general – including entheogens of animal origin (e.g. hallucinogenic fish and toad venom) – has, however, made considerable progress in the sixty-odd years since Cunnison's report; the idea that some intoxicating substance might reside in giraffe livers may no longer be as far-fetched as it seemed to Cunnison. However, to date, proof (or disproof) still waits on detailed analyses of the organ and the beverage made from it.[92]

Arrow/bullet poison

[edit]Certain Tungusic peoples of northeast Asia formerly prepared a type of arrow poison from rotting animal livers, which was, in later times, also applied to bullets. Russian anthropologist S. M. Shirokogoroff wrote that:

- Formerly the using of poisoned arrows was common. For instance, among the Kumarčen, [a subgroup of the Oroqen] even in recent times, a poison was used which was prepared from decaying liver.

- [Note] This has been confirmed by the Kumarčen. I am not competent to judge as to the chemical conditions of production of poison which is not destroyed by the heat of explosion. However, the Tungus themselves compare this method [of poisoning ammunition] with the poisoning of arrows.[94]

Other animals

[edit]

The liver is found in all vertebrates and is typically the largest internal organ. The internal structure of the liver is broadly similar in all vertebrates, though its form varies considerably in different species, and is largely determined by the shape and arrangement of the surrounding organs. Nonetheless, in most species, it is divided into right and left lobes; exceptions to this general rule include snakes, where the shape of the body necessitates a simple cigar-like form.[95]

In neonatal marsupials, it is responsible for the production of blood cells.[42][45][96][44]

An organ sometimes referred to as a liver is found associated with the digestive tract of the primitive chordate amphioxus. Although it performs many functions of a liver, it is not considered a "true" liver but rather a homolog of the vertebrate liver.[97][98][99] The amphioxus hepatic caecum produces the liver-specific proteins vitellogenin, antithrombin, plasminogen, alanine aminotransferase, and insulin/insulin-like growth factor.[100]

See also

[edit]- Gallbladder

- Pancreas

- Spleen

- Johann Joseph Dömling (published Is the Liver a Purifying Organ in 1798)

- Porphyria

References

[edit]- ^ Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- ^ Elias, H.; Bengelsdorf, H. (1 July 1952). "The Structure of the Liver in Vertebrates". Cells Tissues Organs. 14 (4): 297–337. doi:10.1159/000140715. PMID 14943381.

- ^ Abdel-Misih, Sherif R.Z.; Bloomston, Mark (2010). "Liver Anatomy". Surgical Clinics of North America. 90 (4): 643–653. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2010.04.017. PMC 4038911. PMID 20637938.

- ^ a b c "Anatomy and physiology of the liver – Canadian Cancer Society". Cancer.ca. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ a b "Etymology online hepatic". Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Tortora, Gerard J.; Derrickson, Bryan H. (2008). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology (12th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 945. ISBN 978-0-470-08471-7.

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0. OCLC 32308337.

- ^ Zakim, David; Boyer, Thomas D. (2002). Hepatology: A Textbook of Liver Disease (4th ed.). ISBN 978-0-7216-9051-3.

- ^ Basics, Liver. "VA.gov | Veterans Affairs". www.hepatitis.va.gov. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ "Function of the Liver". UPMC | Life Changing Medicine. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ a b Liver Anatomy at eMedicine

- ^ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. p. 878. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ^ "Enlarged liver". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2017-03-21. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ^ Molina, D. Kimberley; DiMaio, Vincent J.M. (2012). "Normal Organ Weights in Men". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 33 (4): 368–372. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad. ISSN 0195-7910. PMID 22182984. S2CID 32174574.

- ^ Molina, D. Kimberley; DiMaio, Vincent J. M. (2015). "Normal Organ Weights in Women". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 36 (3): 182–187. doi:10.1097/PAF.0000000000000175. ISSN 0195-7910. PMID 26108038. S2CID 25319215.

- ^ "Anatomy of the Liver". Liver.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-06-27. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ Renz, John F.; Kinkhabwala, Milan (2014). "Surgical Anatomy of the Liver". In Busuttil, Ronald W.; Klintmalm, Göran B. (eds.). Transplantation of the Liver. Elsevier. pp. 23–39. ISBN 978-1-4557-5383-3.

- ^ "Cantlie's line | Radiology Reference Article". Radiopaedia.org. Archived from the original on 2015-06-27. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ Kuntz, Erwin; Kuntz, Hans-Dieter (2009). "Liver resection". Hepatology: Textbook and Atlas (3rd ed.). Springer. pp. 900–903. ISBN 978-3-540-76839-5.

- ^ a b Singh, Inderbir (2008). "The Liver Pancreas and Spleen". Textbook of Anatomy with Colour Atlas. Jaypee Brothers. pp. 592–606. ISBN 978-81-8061-833-8.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b McMinn, R.M.H. (2003). "Liver and Biliary Tract". Last's Anatomy: Regional and Applied. Elsevier. pp. 342–351. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ Skandalakis, Lee J.; Skandalakis, John E.; Skandalakis, Panajiotis N. (2009). "Liver". Surgical Anatomy and Technique. pp. 497–531. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-09515-8_13. ISBN 978-0-387-09515-8.

- ^ a b c Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary 2012, p. 925.

- ^ Moore, K (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Wolters Kluwer. p. 501. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ Moore, K (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Wolters Kluwer. p. 494. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ "Mickey Mouse sign". Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Kmieć Z (2001). "Introduction — Morphology of the Liver Lobule". Cooperation of Liver Cells in Health and Disease. Advances in Anatomy Embryology and Cell Biology. Vol. 161. pp. iii–xiii, 1–151. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-56553-3_1. ISBN 978-3-540-41887-0. PMID 11729749.

- ^ Pocock, Gillian (2006). Human Physiology (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- ^ a b Kawarada, Y; Das, BC; Taoka, H (2000). "Anatomy of the hepatic hilar area: the plate system". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 7 (6): 580–586. doi:10.1007/s005340070007. PMID 11180890.

- ^ a b "Couinaud classification | Radiology Reference Article". Radiopaedia.org. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ "Three-dimensional Anatomy of the Couinaud Liver Segments". Archived from the original on 2009-02-09. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ Strunk, H.; Stuckmann, G.; Textor, J.; Willinek, W. (2003). "Limitations and pitfalls of Couinaud's segmentation of the liver in transaxial Imaging". European Radiology. 13 (11): 2472–2482. doi:10.1007/s00330-003-1885-9. PMID 12728331. S2CID 34879763.

- ^ a b "The Radiology Assistant: Anatomy of the liver segments". Radiologyassistant.nl. 2006-05-07. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ "The human proteome in liver – The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-21. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220) 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ Kampf, Caroline; Mardinoglu, Adil; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Edlund, Karolina; Lundberg, Emma; Pontén, Fredrik; Nielsen, Jens; Uhlen, Mathias (2014-07-01). "The human liver-specific proteome defined by transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling". The FASEB Journal. 28 (7): 2901–2914. doi:10.1096/fj.14-250555. ISSN 0892-6638. PMID 24648543. S2CID 5297255.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates. Archived from the original on 2017-12-18. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- ^ a b Lade AG, Monga SP (2011). "Beta-catenin signaling in hepatic development and progenitors: which way does the WNT blow?". Dev Dyn. 240 (3): 486–500. doi:10.1002/dvdy.22522. PMC 4444432. PMID 21337461.

- ^ Berg T, DeLanghe S, Al Alam D, Utley S, Estrada J, Wang KS (2010). "β-catenin regulates mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation during hepatogenesis". J Surg Res. 164 (2): 276–285. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2009.10.033. PMC 2904820. PMID 20381814.

- ^ Clemente, Carmin D. (2011). Anatomy a Regional Atlas of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-58255-889-9.

- ^ Egerton, S.; Wan, A.; Murphy, K.; Collins, F.; Ahern, G.; Sugrue, I.; Busca, K.; Egan, F.; Muller, N.; Whooley, J.; McGinnity, P.; Culloty, S.; Ross, R. P.; Stanton, C. (6 March 2020). "Replacing fishmeal with plant protein in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) diets by supplementation with fish protein hydrolysate". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 4194. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.4194E. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-60325-7. PMC 7060232. PMID 32144276.

- ^ a b Old, J.M.; Deane, E.M. (July 2000). "Development of the immune system and immunological protection in marsupial pouch young". Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 24 (5): 445–454. doi:10.1016/S0145-305X(00)00008-2. PMID 10785270.

- ^ Old, Julie M. (May 2016). "Haematopoiesis in Marsupials". Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 58: 40–46. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2015.11.009. PMID 26592963.

- ^ a b Old, J.M; Selwood, L; Deane, E.M (April 2004). "A developmental investigation of the liver, bone marrow and spleen of the stripe-faced dunnart (Sminthopsis macroura)". Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 28 (4): 347–355. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2003.08.004. PMID 14698220.

- ^ a b Old, J. M.; Deane, E. M. (February 2003). "The lymphoid and immunohaematopoietic tissues of the embryonic brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula)". Anatomy and Embryology. 206 (3): 193–197. doi:10.1007/s00429-002-0285-2. PMID 12592570.

- ^ Shneider, Benjamin L.; Sherman, Philip M. (2008). Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease. Connecticut: PMPH-USA. p. 751. ISBN 978-1-55009-364-3.

- ^ a b Human Anatomy & Physiology + New Masteringa&p With Pearson Etext. Benjamin-Cummings Pub Co. 2012. p. 881. ISBN 978-0-321-85212-0.

- ^ a b Human Anatomy & Physiology + New Masteringa&p With Pearson Etext. Benjamin-Cummings Pub Co. 2012. p. 939. ISBN 978-0-321-85212-0.

- ^ Rocha Leão, M.H.M. (2003). "Glycogen". Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. pp. 2930–2937. doi:10.1016/B0-12-227055-X/00563-0. ISBN 978-0-12-227055-0.

- ^ Miller, L. L.; Bale, W. F. (February 1954). "Synthesis of all plasma protein fractions except gamma globulins by the liver; the use of zone electrophoresis and lysine-epsilon-C14 to define the plasma proteins synthesized by the isolated perfused liver". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 99 (2): 125–132. doi:10.1084/jem.99.2.125. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2180344. PMID 13130789.

- ^ Jelkmann, Wolfgang (2001). "The role of the liver in the production of thrombopoietin compared with erythropoietin". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 13 (7): 791–801. doi:10.1097/00042737-200107000-00006. PMID 11474308.

- ^ Human Anatomy & Physiology + New Masteringa&p With Pearson Etext. Benjamin-Cummings Pub Co. 2012. ISBN 978-0-321-85212-0.

- ^ Lautt, WW; Greenway, CV (August 1976). "Hepatic venous compliance and role of liver as a blood reservoir". American Journal of Physiology. Legacy Content. 231 (2): 292–295. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.2.292. PMID 961879.

- ^ "Liver". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "If a person stops consuming the vitamin, the body's stores of this vitamin usually take about 3 to 5 years to exhaust". Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ Timens, Wim; Kamps, Willem A.; Rozeboom-Uiterwijk, Thea; Poppema, Sibrand (September 1990). "Haemopoiesis in human fetal and embryonic liver: Immunohistochemical determination in B5-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues". Virchows Archiv A. 416 (5): 429–436. doi:10.1007/BF01605149. PMID 2107630. S2CID 10436627.

- ^ Nguyen-Lefebvre, Anh Thu; Horuzsko, Anatolij (2015). "Kupffer Cell Metabolism and Function". Journal of Enzymology and Metabolism. 1 (1). PMC 4771376. PMID 26937490.

- ^ Younossi, Zobair M.; Golabi, Pegah; Paik, James M.; Henry, Austin; Van Dongen, Catherine; Henry, Linda (1 April 2023). "The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review". Hepatology. 77 (4): 1335–1347. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004. ISSN 1527-3350. PMC 10026948. PMID 36626630.

- ^ Hepatitis A, B, and C Center: Symptoms, Causes, Tests, Transmission, and Treatments Archived 2016-01-31 at the Wayback Machine. Webmd.com (2005-08-19). Retrieved on 2016-05-10.

- ^ Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ (2015). "Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013". Lancet. 386 (10003): 1546–1555. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. PMID 26231459. S2CID 41847645.

- ^ a b Vos, Theo; Allen, Christine; Arora, Megha; Barber, Ryan M.; Bhutta, Zulfiqar A.; Brown, Alexandria; Carter, Austin; Casey, Daniel C.; Charlson, Fiona J.; Chen, Alan Z.; Coggeshall, Megan; Cornaby, Leslie; Dandona, Lalit; Dicker, Daniel J.; Dilegge, Tina; Erskine, Holly E.; Ferrari, Alize J.; Fitzmaurice, Christina; Fleming, Tom; Forouzanfar, Mohammad H.; Fullman, Nancy; Gething, Peter W.; Goldberg, Ellen M.; Graetz, Nicholas; Haagsma, Juanita A.; Hay, Simon I.; Johnson, Catherine O.; Kassebaum, Nicholas J.; Kawashima, Toana; et al. (2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ "www.hepatitisc.uw.edu". Archived from the original on 2017-08-25.

- ^ "WHO | Hepatitis E". Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

- ^ Dény, P. (2006). "Hepatitis Delta Virus Genetic Variability: From Genotypes I, II, III to Eight Major Clades?". Hepatitis Delta Virus. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 307. pp. 151–171. doi:10.1007/3-540-29802-9_8. ISBN 978-3-540-29801-4. PMID 16903225.

- ^ Rajani R, Melin T, Björnsson E, Broomé U, Sangfelt P, Danielsson A, Gustavsson A, Grip O, Svensson H, Lööf L, Wallerstedt S, Almer SH (Feb 2009). "Budd-Chiari syndrome in Sweden: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and survival – an 18-year experience". Liver International. 29 (2): 253–259. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01838.x. PMID 18694401. S2CID 36353033.

- ^ Hirschfield, GM; Gershwin, ME (Jan 24, 2013). "The immunobiology and pathophysiology of primary biliary cirrhosis". Annual Review of Pathology. 8: 303–330. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164014. PMID 23347352.

- ^ Dancygier, Henryk (2010). Clinical Hepatology Principles and Practice of. Springer. pp. 895–. ISBN 978-3-642-04509-7. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ Saxena, Romil; Theise, Neil (2004). "Canals of Hering: Recent Insights and Current Knowledge". Seminars in Liver Disease. 24 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1055/s-2004-823100. PMID 15085485. S2CID 260317971.

- ^ Muriel, Pablo; Arauz, Jonathan (2010-07-01). "Coffee and liver diseases". Fitoterapia. 81 (5): 297–305. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.10.003. ISSN 0367-326X. PMID 19825397.

- ^ "Coffee and your liver FAQs". British Liver Trust. February 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Extraintestinal Complications: Liver Disease Archived 2010-11-21 at the Wayback Machine Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America. Retrieved 2010-01-22

- ^ Ghent, Cam N (2009). "Who should be performing liver biopsies?". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 23 (6): 437–438. doi:10.1155/2009/756584. PMC 2721812. PMID 19543575.

- ^ Sheporaitis, L; Freeny, PC (1998). "Hepatic and portal surface veins: A new anatomic variant revealed during abdominal CT". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 171 (6): 1559–1564. doi:10.2214/ajr.171.6.9843288. PMID 9843288.

- ^ Defrances, Marie C.; Michalopoulos, George K. (2011). "Liver Regeneration and Partial Hepatectomy: Process and Prototype". Liver Regeneration. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1515/9783110250794.1. ISBN 978-3-11-025078-7.

- ^ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (1999). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8089-2302-2.

- ^ Chu, Jaime; Sadler, Kirsten C. (2009). "New school in liver development: Lessons from zebrafish". Hepatology. 50 (5): 1656–1663. doi:10.1002/hep.23157. PMC 3093159. PMID 19693947.

- ^ W.T. Councilman (1913). "Two". Disease and Its Causes. New York Henry Holt and Company London Williams and Norgate The University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- ^ Suzuki K, Tanaka M, Watanabe N, Saito S, Nonaka H, Miyajima A (2008). "p75 Neurotrophin receptor is a marker for precursors of stellate cells and portal fibroblasts in mouse fetal liver". Gastroenterology. 135 (1): 270–281.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.075. PMID 18515089.

- ^ Tietz PS, Larusso NF (May 2006). "Cholangiocyte biology". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 22 (3): 279–287. doi:10.1097/01.mog.0000218965.78558.bc. PMID 16550043. S2CID 38944986.

- ^ An argument for the ancient Greek's knowing about liver regeneration is provided by Chen, T.S.; Chen, P.S. (1994). "The myth of Prometheus and the liver". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 87 (12): 754–755. PMC 1294986. PMID 7853302. Counterarguments are provided by Tiniakos, D.G.; Kandilis, A.; Geller, S.A. (2010). "Tityus: A forgotten myth of liver regeneration". Journal of Hepatology. 53 (2): 357–361. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.032. PMID 20472318. and by Power, C.; Rasko, J.E. (2008). "Whither prometheus' liver? Greek myth and the science of regeneration". Annals of Internal Medicine. 149 (6): 421–426. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.689.8218. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-6-200809160-00009. PMID 18794562. S2CID 27637081.

- ^ Bramstedt K (2006). "Living liver donor mortality: where do we stand?". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101 (4): 755–759. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00421.x. PMID 16494593. S2CID 205786066.

- ^ Spence, Lewis (2010). Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria. Cosimo. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-61640-464-2.

Now among people in a primitive state of culture the soul is almost invariably supposed to reside in the liver instead of in the heart or brain.

- ^ Krishna, Gopi; Hillman, James (1970). Kundalini – the evolutionary energy in man. London: Stuart & Watkins. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-57062-280-9. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ The Great Battle Of Badar (Yaum-E-Furqan) Archived 2014-06-30 at the Wayback Machine. Shawuniversitymosque.org (2006-07-08). Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^ "hígado". Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish) (23.4 ed.). ASALE-RAE. 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

Ánimo, valentía. U. m. en pl.

- ^ Azkue, Resurrección María de (1905). "gibel". Diccionario vasco-español-francés ... Dictionnaire basque-espagnol-français . (in Spanish and French). Bilbao, Dirección del autor. p. 345. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

(Bc, BN-s, R) cachaza, calme

- ^ כלו בדמעות עיני חמרמרו מעי נשפך לארץ כבדי על שבר בת עמי בעטף עולל ויונק ברחבות קריה "My eyes terminated with tears, my intestines overturned with bitterness, my liver spilled to the earth on the breaking of my nation's daughter when a suckling baby lies in the town squares" (Lamentations 2:11) this could be interpreted to be read as my honor spilled, or myself being spilled).

- ^ Kavod - Honor (in Hebrew, Israeli Linguist Ruvik Rosenthal's website). Rosenthal hypothesized that the term's usage to describe heaviness comes perhaps from the liver being the heaviest of all body parts in some farm animals or in humans.

- ^ See Kabadu in Akkadian, (From online dictionary at Association Assyrophile de France organization website)

- ^ "Foie". Larousse.fr. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- ^ Schwabe, Calvin W. (1979). Unmentionable Cuisine. University of Virginia Press. pp. 313–. ISBN 978-0-8139-1162-5. Archived from the original on 2015-10-26. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ^ a b c d Rudgley, R. (1998). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances. Abacus. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-349-11127-8.

- ^ a b Cunnison, Ian (1958). "Giraffe hunting among the Humr tribe". SNR. 39: 49–60.

- ^ Shirokogoroff, S.M. (1935). Psychomental Complex of the Tungus. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. p. 89.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 354–355. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^ Old, J.M.; Selwood, L.; Deane, E.M. (2003). "A Histological Investigation of the Lymphoid and Immunohaematopoietic Tissues of the Adult Stripe-Faced Dunnart (Sminthopsis macroura)". Cells Tissues Organs. 173 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1159/000068946. PMID 12649589.

- ^ Yuan, Shaochun; Ruan, Jie; Huang, Shengfeng; Chen, Shangwu; Xu, Anlong (February 2015). "Amphioxus as a model for investigating evolution of the vertebrate immune system". Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 48 (2): 297–305. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2014.05.004. PMID 24877655.

- ^ Yu, Jr-Kai Sky; Lecroisey, Claire; Le Pétillon, Yann; Escriva, Hector; Lammert, Eckhard; Laudet, Vincent (2015). "Identification, evolution and expression of an insulin-like peptide in the cephalochordate Branchiostoma lanceolatum". PLOS ONE. 10 (3) e0119461. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019461L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119461. PMC 4361685. PMID 25774519.

- ^ Escriva, Hector; Chao, Yeqing; Fan, Chunxin; Liang, Yujun; Gao, Bei; Zhang, Shicui (2012). "A novel serpin with antithrombin-like activity in Branchiostoma japonicum: Implications for the presence of a primitive coagulation system". PLOS ONE. 7 (3) e32392. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732392C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032392. PMC 3299649. PMID 22427833.

- ^ Guo, Bin; Zhang, Shicui; Wang, Shaohui; Liang, Yujun (2009). "Expression, mitogenic activity and regulation by growth hormone of growth hormone / insulin-like growth factor in Branchiostoma belcheri". Cell and Tissue Research. 338 (1): 67–77. doi:10.1007/s00441-009-0824-8. PMID 19657677. S2CID 21261162.

Works cited

[edit]- Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier / Saunders. 2012. ISBN 978-1-4557-0985-4.

- Young, Barbara; O'Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (4 November 2013). Wheater's Functional Histology: A text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-4747-3.

External links

[edit]- Liver at the Human Protein Atlas

- VIRTUAL Liver – online learning resource

- Liver enzymes

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 801–803. with several diagrams.

- Rizi, Farid (14 January 2022). "Beaver tail liver". Radiopaedia.org. doi:10.53347/rID-96561.