Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ground-controlled interception

View on WikipediaGround-controlled interception (GCI) is an air defence tactic whereby one or more radar stations or other observational stations are linked to a command communications centre which guides interceptor aircraft to an airborne target. This tactic was pioneered during World War I by the London Air Defence Area organization, which became the Royal Air Force's Dowding system in World War II, the first national-scale system. The Luftwaffe introduced similar systems during the war, but most other combatants did not suffer the same threat of air attack and did not develop complex systems like these until the Cold War era.

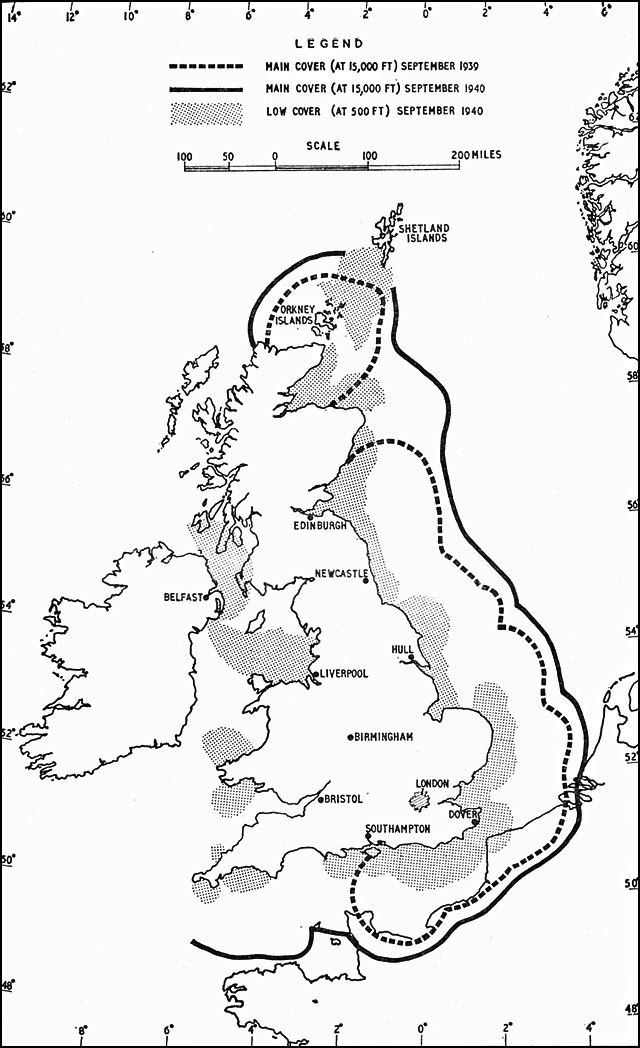

Today the term GCI refers to the style of battle direction, but during WWII it also referred to the radars themselves. Specifically, the term was used to describe a new generation of radars that spun on their vertical axis in order to provide a complete 360 degree view of the sky around the station. Previous systems, notably Chain Home (CH), could only be directed along angles in front of the antennas, and were unable to direct traffic once it passed behind their shore-side locations. GCI radars began to replace CH starting in 1941/42, allowing a single station to control the entire battle from early detection to directing the fighters to intercept.

GCI systems grew in size and sophistication during the post-war era, in response to the overwhelming threat of nuclear attack. The US' SAGE system was perhaps the most complex attempted, using building-filling computers linked to dozens of radars and other sensors to automate the entire task of identifying an enemy aircraft's track and directing interceptor aircraft or surface-to-air missiles against it. In some cases, SAGE sent commands directly to the aircraft's autopilot, bringing the aircraft within attack range entirely under computer control. The RAF counterpart, ROTOR remained a mostly manual system.

Today, GCI is still important for most nations, although Airborne Early Warning and Control, with or without support from GCI, generally offers much greater range due to the much more distant radar horizon.

World War II

[edit]

In the original Dowding system of fighter control, information from the Chain Home coastal radar stations was relayed by phone to a number of operators on the ground floor of the "filter room" at Fighter Command's headquarters at RAF Bentley Priory. Here the information from the radar was combined with reports from the Royal Observer Corps and radio direction finding systems and merged to produce a single set of "tracks", identified by number. These tracks were then telephoned to the Group headquarters that would be responsible for dealing with that target. Group would assign fighter squadrons to the tracks, and phone the information to Section headquarters, who were in direct contact with the fighters. These fighter aircraft could then be "scrambled" to intercept the aircraft.

Because the Chain Home radar stations faced out to sea, once airborne intruders had crossed the British coast they could no longer be tracked by radar; and accordingly the interception direction centres relied on visual and aural sightings of the Observer Corps for continually updated information on the location and heading of enemy aircraft formations. While this arrangement worked acceptably during the daylight raids of the Battle of Britain, subsequent bombing attacks of The Blitz demonstrated that such techniques were wholly inadequate for identifying and tracking aircraft at night.

Experiments in addressing this problem started with manually directed radars being used as a sort of radio-searchlight, but this proved too difficult to use in practice. Another attempt was made by using a height finding radar turned on its side in order to scan an arc in front of the station. This proved very workable, and was soon extended to covering a full 360 degrees by making minor changes to the support and bearing systems. Making a display system, the "Plan Position Indicator" (PPI), that displayed a 360 degree pattern proved surprisingly easy, and test systems were available by late 1940.

Starting in 1941 the RAF began deploying production models of the GCI radar, first with expedient solutions known as the AMES Type 8, and then permanent stations based on the much larger AMES Type 7. Unlike the earlier system where radar data was forwarded by telephone and plotted on a map, GCI radars combined all of these functions into a single station. The PPI was in the form of a 2D top-down display showing both the targets and the intercepting night fighters. Interceptions could be arranged directly from the display, without any need to forward the information over telephone links or similar. This not only greatly eased the task of arranging the interception, but greatly reduced the required manpower as well.

As the system became operational the success of the RAF night fighter force began to shoot up. This was further aided by the introduction of the Bristol Beaufighter and its AI Mk. IV radar which became available in numbers at the same time. These two systems proved to be a potent combination, and interception rates doubled every month from January 1941 until the Luftwaffe campaign ended in May.

The Germans were quite slow to follow in terms of PPI and did not order operational versions of their Jagdschloss radar until late in 1943, with deliveries being relatively slow after that. Many were still under construction when the war ended in 1945.

Post WWII

[edit]More recently, in both the Korean and Vietnam wars, the North Koreans and North Vietnamese had important GCI systems which helped them harass the opposing forces (although in both cases due to the superiority in the number of US planes the effect was eventually minimised[citation needed]). GCI was important to the US and allied forces during these conflicts also, although not so much as for their opponents.

The most advanced GCI system deployed to date was the US's Semi Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) system. SAGE used massive computers to combine reports sent in via teleprinter from the Pinetree Line and other radar networks to produce a picture of all of the air traffic in a particular sector's area. The information was then displayed on terminals in the building, allowing operators to pick defensive assets (fighters and missiles) to be directed onto the target simply by selecting them on the terminal. Messages would then automatically be routed back out via teleprinter to the fighter airbases with interception instructions on them.

The system was later upgraded to relay directional information directly to the autopilots of the interceptor aircraft like the F-106 Delta Dart. The pilot was tasked primarily with getting the aircraft into the air (and back), and then flying in a parking orbit until called for. When an interception mission started, the SAGE computers automatically flew the plane into range of the target, allowing the pilot to concentrate solely on operating the complex onboard radar.

The RAF's post-war system was originally ROTOR, which was largely an expanded and rationalized version of their wartime system and remained entirely manual in operation. This was upset by the introduction of the AMES Type 80 radar, which was originally intended as a very long-range early warning system for ROTOR but demonstrated its ability to control interceptions as well. This led to the abandonment of the ROTOR network and its operation being handled at the Type 80 "Master Radar Stations". In the 1960s the Linesman/Mediator project looked to computerize the system in a fashion similar to SAGE, but was years late, significantly underpowered, and never operated properly. There was some thought given to sending directions to the English Electric Lightning interceptors in a fashion similar to SAGE, but this was never implemented.

GCI is typically augmented with the presence of extremely large early warning radar arrays, which could alert GCI to inbound hostile aircraft hours before they arrive, giving enough time to prepare and launch aircraft and set them up for an intercept either using their own radars or with the assistance of regular radar stations once the bogeys approach their coverage. An example of this type of system is Australia's Jindalee over-the-horizon radar. Such radars typically operate by bouncing their signal off layers in the atmosphere.

Airborne Early Warning and Control

[edit]This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2013) |

In more recent years, GCI has been supplanted, or replaced outright, with the introduction of Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C, often called AWACS) aircraft. AEW&C tends to be superior in that, being airborne and being able to look down, it can see targets fairly far away at low level, as long as it can pick them out from the ground clutter. AEW&C aircraft are extremely expensive, however, and generally require aircraft to be dedicated to protecting them. A combination of both techniques is really ideal, but GCI is typically only available in the defence of one's homeland, rather than in expeditionary types of battles.

The strengths of GCI are that it can cover far more airspace than AEW&C without costing as much and areas that otherwise would be blind-spots for AEW&C can be covered by cleverly placed radar stations. AEW&C also relies on aircraft which may require defence and a few aircraft are more vulnerable than many ground-based radar stations. If a single AEW&C aircraft is shot down or otherwise taken out of the picture, there will be a serious gap in air defence until another can replace it, where in the case of GCI, many radar stations would have to be taken off the air before it became a serious problem. In both cases a strike on a command center could be very serious.

Either GCI or AEW&C can be used to give defending aircraft a major advantage during the actual interception by allowing them to sneak up on enemy aircraft without giving themselves away by using their own radar sets. Typically, to perform an interception by themselves beyond visual range, the aircraft would have to search the sky for intruders with their radars, the energy from which might be noticed by the intruder's radar warning receiver (RWR) electronics, thus alerting the intruders that they may be coming under attack. With GCI or AEW&C, the defending aircraft can be vectored to an interception course, perhaps sliding in on the intruder's tail position without being noticed, firing passive homing missiles and then turning away. Alternatively, they could turn their radars on at the final moment, so that they can get a radar lock and guide their missiles. This greatly increases the interceptor's chance of success and survival.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]External links

[edit]- Ground Controlled Interception Radars in Operation Neptune/Overlord Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)