Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pinetree Line

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2012) |

| Pinetree Line | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1951–1991 |

| Country | Canada |

| Branch | Royal Canadian Air Force United States Air Force |

| Type | Early-warning radar |

| Role | Continental Air Defense |

| Part of | North American Aerospace Defense Command |

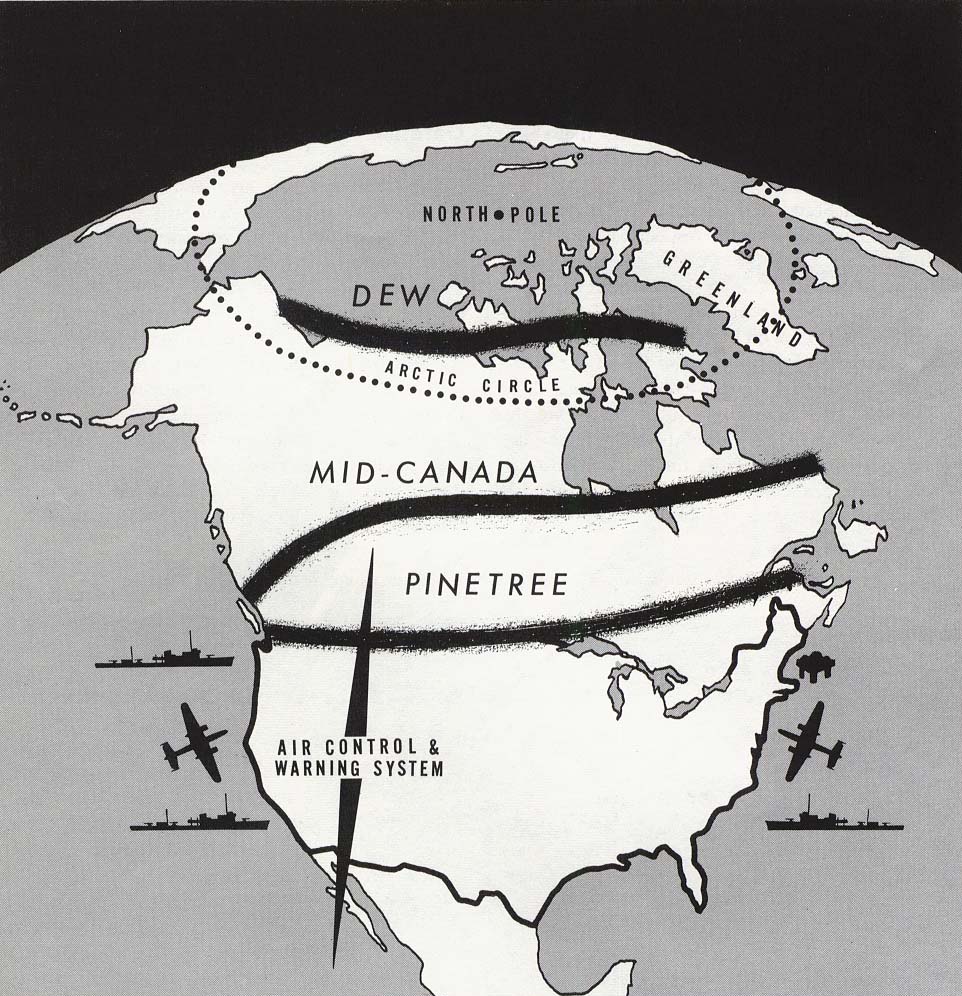

The Pinetree Line was a series of radar stations located across southern Canada at about the 50th parallel north, along with a number of other stations located on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Run by North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) (after its creation), over half were staffed by United States Air Force personnel with the balance operated by the Royal Canadian Air Force. The line was the first coordinated system for early detection of a Soviet bomber attack on North America. Its radar technology quickly became outdated, and the line was in full operation only for a short time.

History

[edit]

Plans for what would become the Pinetree Line were underway as early as 1946 within the Permanent Joint Board on Defense (PJBD), a Canadian-U.S. organization. However, the costs of running such a system in the post-war era was too high, and instead Canada concentrated on the areas around Ontario and Quebec, while the United States set up stations in the Midwest and along the eastern seaboard. With the successful test of an atomic bomb in the USSR, plans changed considerably. In 1949 Congress agreed to a $161 million construction program in co-operation with the RCAF, for a continuous line of stations across southern Canada. The USAF's Continental Air Command and the RCAF met in October 1950 to start planning, and in January 1951 the PJBD presented Recommendation 51/1 for the Extension of the Continental Radar Defence System. The USAF later requested an additional set of six (potentially) mobile stations to provide low-level coverage. Later, it was learned the original radar systems performed better than expected, hence a number of the mobile sites were never deployed.

The system was eventually deployed as a series of 33 main stations and 6 smaller "gap fillers". The majority of these ran in a line at about the 53rd parallel in the west (to offer coverage of major Canadian cities) and about the 50th parallel in the east. A second line ran up the eastern seaboard from the southern tip of Nova Scotia to the southern tip of Baffin Island. Of these, 22 of the main stations and all of the gap fillers were paid for by the USAF, leaving 11 to the RCAF. However 16 of the main stations were staffed by RCAF personnel. On 1 January 1955, the system was officially handed over to RCAF command, and over time an additional 10 stations were added. The stations on the east coast used the Pole Vault system for communication.

The Pinetree Line had several technical problems that limited its usefulness almost immediately. For one, the system used a simple pulse radar technique, which made it unable to detect targets close to the ground due to radar clutter as well as being trivially easy to jam using the recently introduced carcinotron tube. Another was that its location near population centres meant it offered only a last minute warning, and as the USSR moved to jet-powered bombers the warning time was reduced. Studies were already underway in 1951 to build a series of Doppler bistatic radar stations somewhat farther north, which would develop into the Mid-Canada Line. By 1957, just over a year after the Mid-Canada Line was operational, a more advanced long-range search radar, mainly in the Canadian north and Alaska were deployed comprising the Distant Early Warning Line.

The Pinetree stations were kept operational during this period, and most underwent modifications as a part of the deployment of the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE). SAGE dramatically reduced the workload at the stations, cutting staff requirements by well over half. By the later 1950s some were being mothballed as newer systems came on line to the north. Nevertheless, many of the Pinetree stations were kept operational into the 1980s, particularly on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

Radar stations

[edit]Initial sort is based on longitude from east to west.

See also

[edit]- List of Royal Canadian Air Force stations

- United States general surveillance radar stations

- Radar Station, a 1953 short documentary about the Pinetree Line

- Continental Air Defense Integration North

- Continental Air Defense Command

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

- A Handbook of Aerospace Defense Organization 1946–1980, by Lloyd H. Cornett and Mildred W. Johnson, Office of History, Aerospace Defense Center, Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado

- The Pinetree Line

- "The Pinetree Line Home Page". Military Communications and Electronics Museum.