Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

| Part of a series on |

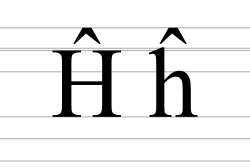

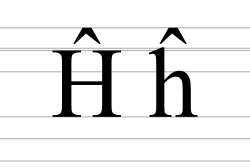

Ĥ or ĥ is a letter of some extended Latin alphabets, most prominently a consonant in Esperanto orthography, where it represents a voiceless velar fricative [x] or voiceless uvular fricative [χ]. Its name in Esperanto is ĥo (pronounced /xo/), or ĥi in the Kalocsay abecedary.

It is also used in the revised Demers/Blanchet/St Onge orthography for Chinook Jargon.[1]

In the case of the minuscule, some fonts place the circumflex centered above the entire base letter h, others over the riser of the letter, and others over the shoulder.

Ĥ is the eleventh letter in Esperanto orthography. Although it is written as hx and hh respectively in the x-system and h-system workarounds, it is normally written as H with a circumflex: ĥ.

History

[edit]"Ĥ" was created by adding a circumflex to an ordinary "H". It first appeared as part of the alphabet of the international language Esperanto, with the publication of the Unua Libro on 26 July 1887 marking the beginning of its wider usage.[2] Like all other non-basic Latin letters in the Esperanto alphabet, it was inspired by Western Slavic Latin alphabets (e.g. Czech), but uses a circumflex instead of a caron — most likely to make the orthography appear more international (i.e. less Slavic) and more compatible with French typewriters, which were in general use at the time and had a dead key for the circumflex, allowing it to be typed over any character.

Reported end

[edit]⟨Ĥ⟩ was always the least frequent letter in Esperanto orthography,[a] occurring mostly in words with Greek etymologies, where it represented a Romanized chi (in fact its name in the Kalocsay abecedary, ĥi, was most likely inspired by this usage). Since chi is pronounced [k] in most languages, neologistic equivalents soon appeared[why?] in which ⟨ĥ⟩ was replaced by ⟨k⟩, such as teĥniko → tekniko ("technology") and ĥemio → kemio ("chemistry"). Such changes were probably due to the 'k' sound being easier to pronounce by most European speakers, and the resulting word sounding more similar to the native equivalent. Some other replacements followed different patterns, such as ĥino → ĉino ("Chinese [person]").

These additions and replacements came very early and were in general use by World War I. Since then, the end of ⟨ĥ⟩ has been often discussed, but has never really happened. In modern times (post-World War II), no new coinages intended to replace words with ⟨ĥ⟩ in them have seen general use, with the notable of exception of koruso for ĥoro ("chorus"). Some words originally containing a ⟨ĥ⟩ are preferred to existing replacements (old or new), such as ĥaoso vs. kaoso ("chaos").[citation needed]

Several words commonly use ⟨ĥ⟩, particularly those not derived from Greek words (ĥano ("khan"), ĥoto ("jota"), Liĥtenŝtejno ("Liechtenstein"), etc.) or those in which there is another word that uses "k" in that context. The latter include:

- eĥo ("echo") ≠ eko ("beginning")

- ĉeĥo ("Czech") ≠ ĉeko ("bank check")

- ĥoro ("chorus") ≠ koro ("heart") ≠ horo ("hour")

Other uses

[edit]- A 'Ĥ' was used in the stage name of the 1980s Italo disco singer CĤATO.[3]

- In quantum mechanics, the Hamiltonian of a system is typically denoted by (where the hat indicates that it is an operator), especially in the Wheeler–DeWitt equation.

Computing codes

[edit]| Preview | Ĥ | ĥ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H WITH CIRCUMFLEX | LATIN SMALL LETTER H WITH CIRCUMFLEX | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 292 | U+0124 | 293 | U+0125 |

| UTF-8 | 196 164 | C4 A4 | 196 165 | C4 A5 |

| Numeric character reference | Ĥ |

Ĥ |

ĥ |

ĥ |

| Named character reference | Ĥ | ĥ | ||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lang, George (2009). Making Wawa: The Genesis of Chinook Jargon. UBC Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0774815277.

- ^ "Unua Libro en Esperanto (First Book in Esperanto) - National Geographic Society". nationalgeographic.org. 2017-10-20. Archived from the original on 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- ^ "Chato – No No No". Discogs. Although the circumflex isn't in the text of the webpage, it is used in his stage name as shown on the record jacket: CĤATO.

Linguistic usage

Esperanto orthography

In Esperanto, the letter ĥ represents the voiceless velar fricative sound /x/, pronounced similarly to the "ch" in Scottish "loch" or German "Bach".[4] This phonetic value, denoted in the International Phonetic Alphabet as , distinguishes it from the plain "h," which is a voiceless glottal fricative.[5] L. L. Zamenhof introduced ĥ in 1887 as part of Esperanto's 28-letter alphabet, specifically to accommodate non-Romance sounds absent from many European languages.[4] ĥ is the least frequent letter in Esperanto, appearing in approximately 0.01% of characters across analyzed texts, and thus in fewer than 0.1% of words overall.[6] It occurs primarily in loanwords derived from Greek, where it transliterates the ancient Greek chi (χ).[7] Representative examples include eĥo ("echo," from Greek ἦχος), monaĥo ("monk," from Greek μοναχός), ĥoro ("choir," from Greek χορός), ĉeĥo ("Czech," from Czech Čech), and in proper names like Baĥ (Bach).[8] Orthographic rules stipulate that ĥ functions as a standalone letter for its unique sound, without forming digraphs or combinations with other letters.[5] Its use with the circumflex diacritic is mandatory in official Esperanto writing, as defined by the Fundamento de Esperanto, though informal systems like "hh" (h-convention) or "hx" (x-system) serve as substitutes when diacritics cannot be rendered.[5]Other languages and romanizations

The letter ĥ appears only sporadically in extended Latin scripts beyond Esperanto, with no standard role in the orthography of any natural language. In constructed languages inspired by Esperanto, such as Ido, diacritics including ĥ were eliminated; the corresponding /x/ sound is rendered with "h".[9] Non-standard or proposed uses persist in some constructed languages modeled on Esperanto and in linguistic fieldwork notations for velar fricatives, but these remain marginal and undocumented in major orthographic systems. The /x/ sound occurs in various global languages, including Dutch, German, and Scottish Gaelic, but is typically represented without diacritics in their standard scripts. ĥ is distinct from similar diacritic-modified h letters employed in other romanizations. For instance, ḫ (h with breve below) denotes the voiceless velar or uvular fricative /x/ or /χ/ in systems like DIN 31635 for Arabic transliteration of the letter خ (khāʾ).[10] By contrast, ħ (h with stroke) represents the voiceless pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet and serves as a dedicated letter in Maltese orthography for the sound akin to Arabic ح (ḥāʾ), often pharyngealizing adjacent vowels.[11]Scientific and mathematical usage

Quantum mechanics

In quantum mechanics, Ĥ denotes the Hamiltonian operator, which represents the total energy of a quantum system, comprising both kinetic and potential energy components.[12] This operator acts on the wavefunction of the system to yield energy-related information, distinguishing it from the classical Hamiltonian function H./04%3A_The_Postulates_of_Quantum_Mechanics/4.06%3A_The_Hamiltonian_and_Time-Evolution) For a single particle in one dimension, the Hamiltonian operator takes the form where is the reduced Planck's constant, is the particle's mass, and is the potential energy function.[12] This expression arises from quantizing the classical Hamiltonian by replacing momentum with the operator and incorporating the position-dependent potential./04%3A_The_Postulates_of_Quantum_Mechanics/4.06%3A_The_Hamiltonian_and_Time-Evolution) The Hamiltonian plays a central role in the time-independent Schrödinger equation, , where is the wavefunction and is the energy eigenvalue. This eigenvalue equation determines the stationary states and discrete energy levels of bound quantum systems, derived from the classical Hamiltonian through quantization rules such as those proposed by Schrödinger.[13] The notation Ĥ, using the circumflex to indicate an operator, was adopted in the 1920s by physicists including Erwin Schrödinger and Werner Heisenberg to differentiate quantum operators from classical variables.[14] Schrödinger introduced the foundational equation in his 1926 paper "Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem," where the operator form emerged as an analogy to the classical energy function, though the hat notation became standardized in subsequent literature.[13] In applications, Ĥ is essential for solving energy levels in atomic and molecular systems; for instance, the hydrogen atom Hamiltonian yields the quantized energy spectrum , confirming Bohr's model predictions and enabling the understanding of atomic spectra./08%3A_The_One-Dimensional_Harmonic_Oscillator/8.05%3A_The_Hydrogen_Atom) Similar forms are used for molecular vibrations and quantum many-body problems, underpinning advancements in quantum chemistry and condensed matter physics.Other notations

In functional analysis, the circumflex accent on , denoted , is frequently employed as part of the hat operator to represent the Fourier transform applied to functions. For example, the Fourier transform of a function is standardly written as , and an analogous notation applies to functions such as , yielding to indicate the transformed version in frequency space. This convention facilitates analysis of signals and distributions in spaces and higher dimensions.[15] In control theory and engineering, commonly signifies estimated or approximated system components, such as transfer functions or parameters in dynamic models. For instance, in adaptive control and system identification, denotes the estimated transfer function derived from frequency-domain data, enabling predictions of system behavior under uncertainty, as seen in models of visuomotor delays in biological systems. In Kalman filtering contexts, may represent the estimated observation matrix, updating predictions of states like position or velocity from noisy measurements.[16] In statistics, particularly linear regression, the hat matrix—often denoted but occasionally to emphasize its role—projects observed responses onto the column space of the design matrix , yielding fitted values via . This idempotent and symmetric matrix quantifies leverage and influence of data points, though the plain is more prevalent than the circumflex variant in standard notation. Rare applications appear in other physics domains, such as general relativity and field theory, where or hatted variants like indicate modified metrics or tensors in specific coordinate systems or Weyl-invariant formulations, primarily serving as an emphasized form of . The circumflex in generally signals operator status or estimation, aligning with broader mathematical conventions for denoting transformations; it must not be confused with , the reduced Planck's constant, or the distinct Maltese letter .[15]Encodings and technical representation

Unicode and character codes

The character Ĥ is encoded in Unicode as U+0124, officially named LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H WITH CIRCUMFLEX, while its lowercase counterpart ĥ is U+0125, LATIN SMALL LETTER H WITH CIRCUMFLEX.[17] These precomposed characters allow direct representation of the letter with its circumflex accent without requiring separate combining diacritics. Both code points belong to the Latin Extended-A block (U+0100–U+017F), which supports additional Latin letters used in various European languages and constructed languages like Esperanto.[17] This block was introduced in Unicode version 1.0 (1991), but U+0124 and U+0125 were specifically added in version 1.1 (June 1993) to accommodate extended Latin scripts. In HTML, Ĥ can be represented using the named entity Ĥ or the decimal numeric entity Ĥ (equivalent to hexadecimal Ĥ), and ĥ using ĥ or ĥ (ĥ).[18] These entities ensure consistent rendering across web browsers supporting HTML5 standards. For legacy 8-bit encodings, ISO/IEC 8859-3 (Latin-3, designed for Southern European languages including Esperanto support) assigns Ĥ to byte 0xA6 and ĥ to 0xB6.[19] Windows-1257 (code page 1257, for Baltic languages) does not directly include these characters, often mapping them to basic H (0x48 and 0x68) or requiring Unicode fallback in modern implementations.[20] Standard system fonts such as Arial Unicode MS and Times New Roman (post-2000 versions) fully support rendering of Ĥ and ĥ, as they include the Latin Extended-A glyphs. However, pre-2000 operating systems and fonts often faced rendering issues with diacritics like the circumflex, leading to fallback to basic H or visual glitches in non-Unicode environments. In the Unicode Collation Algorithm (UCA), Ĥ and ĥ are sorted immediately after plain H (U+0048/h) in primary weight for Latin-script collation sequences, treating the circumflex as a non-ignorable modifier to maintain linguistic order in languages using extended Latin alphabets.Input and display methods

Input and display methods for the letter Ĥ, which features a circumflex accent on H, vary across operating systems, software applications, and devices, primarily due to its use in Esperanto orthography and occasional mathematical notations. On desktop computers, specialized keyboard layouts facilitate direct typing. For Windows, users can create or install custom Esperanto keyboard layouts using the Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator, which allows mapping ĥ to combinations like Right-Alt + H on a QWERTY keyboard.[21] Standard QWERTY layouts with dead key support enable input by pressing the circumflex dead key (often ^) followed by H.[22] On Linux systems, the Compose key provides sequence-based input, such as Compose + ^ + h to produce ĥ, configurable through system settings like those in KDE or GNOME.[23] In software environments, input methods cater to document creation and typesetting. LaTeX supports ĥ via the babel package with Esperanto option, where typing c^, g^, h^, j^, s^, or u^ automatically generates the accented letters, including ĥ for h^; alternatively, ^{h} or \hat{h} can be used explicitly for mathematical contexts.[24] In Microsoft Word, ĥ is inserted through the Insert > Symbol dialog, selecting it from the Latin Extended-A subset, or via AutoCorrect by defining shortcuts like "^h" to replace with ĥ.[25] For mobile devices, dedicated keyboards simplify input. On Android, Google's Gboard includes built-in Esperanto support, accessible by enabling the language in settings, allowing direct taps for ĥ among other diacritics.[26] iOS lacks native Esperanto support but accommodates third-party apps like Esperanta Klavaro, which add a full QWERTY layout with ĥ accessible via long-press or dedicated keys.[27] Web browsers on desktops and mobiles often leverage the Compose key or on-screen virtual keyboards for input, with sequences like ^ followed by h in compatible interfaces. Display of ĥ relies on Unicode compatibility, with full support in UTF-8 encoding for modern web pages under HTML5, ensuring proper rendering in browsers like Chrome and Firefox when the document declares UTF-8 charset.[28] In non-supporting or legacy systems, fallback conventions include ASCII approximations like "H^" for visual representation or substitutions in Esperanto text. For environments without diacritic support, the h-system replaces ĥ with "hh" (h followed by h), as outlined in Zamenhof's Fundamento de Esperanto, while the x-system uses "hx" (h followed by x) for unambiguous conversion, with the latter gaining prevalence in digital contexts due to automated transliteration tools.[29] These methods ensure accessibility across platforms, though UTF-8 adoption minimizes the need for fallbacks in contemporary use.Historical development

Origins and adoption

The circumflex diacritic (^) originated in ancient Greek polytonic orthography around the 3rd century BCE, where it was introduced by the scholar Aristophanes of Byzantium as one of three accent marks—alongside the acute and grave—to indicate pitch contours on vowels.[30] Specifically, the circumflex denoted a perispomenon accent, representing a high-low pitch fall on the final syllable of a word, typically over long vowels.[31] This system marked a shift from earlier oral traditions to written notation for prosody in Greek texts. The diacritic later entered Latin scripts through scholarly transmission, evolving into a tool for indicating vowel length or historical letter loss. In French orthography, it was systematically adopted in the 16th century to signal contractions, such as the elision of an 's' before certain vowels (e.g., distinguishing forms like fête from earlier fest with a lengthened vowel).[32] Before its incorporation into Esperanto, 19th-century phonetic transcription systems used various modified Latin letters and diacritics on 'h' to represent the voiceless velar fricative /x/, a sound common in languages like German (as in Bach) and Scottish English (as in loch). Linguists such as Alexander John Ellis employed modified Latin letters, including diacritics on 'h', in their palaeotype and other notations to transcribe non-English sounds accurately for dialect studies and comparative linguistics.[33] This usage filled gaps in the standard Latin alphabet, which lacked a dedicated symbol for the /x/ phoneme prevalent in Germanic and Slavic languages—a reflex of Proto-Indo-European velar fricatives altered by sound shifts like Grimm's Law.[34] L. L. Zamenhof selected ĥ for his constructed language in 1887, as detailed in the inaugural Unua Libro, to denote the voiceless velar fricative /x/ and extend the Latin alphabet without introducing entirely new characters. This choice addressed the need for a neutral, phonetic script capable of representing sounds absent in Romance languages but familiar in Zamenhof's Polish-Jewish milieu, where /x/ occurs in Polish (e.g., chleb) and Yiddish (e.g., khave).[35] His multilingual upbringing in Bialystok, amid Russian, Polish, German, and Yiddish influences, informed this decision, prioritizing simplicity and international accessibility over ethnocentric bias.[36] Printing the Unua Libro in Warsaw posed significant challenges in 1887, as local presses lacked typefaces for Esperanto's diacritics, including ĥ; Zamenhof resorted to substitutions like 'h' alone or descriptive notes, with some copies featuring handwritten accents added post-printing.[37] Funded by personal resources, the initial Russian edition relied on Chaim Kelter's facilities, but technical limitations delayed full typographic implementation until subsequent reprints. By the early 1900s, as Esperanto communities expanded globally—reaching thousands of adherents through clubs and publications in Europe, Asia, and the Americas—dedicated typefaces emerged, standardizing ĥ in print and influencing minor scripts like those in constructed languages or transliterations.[38] The letter's adoption solidified at the 1905 World Esperanto Congress in Boulogne-sur-Mer, where orthographic fidelity became a hallmark of the movement.[37]Evolution and reform proposals

The Fundamento de Esperanto, published in 1905 by L. L. Zamenhof, codified the language's orthography and grammar, officially including ĥ among the six letters with diacritics (ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ) to represent distinct sounds, such as the voiceless velar fricative.[5] Although ĥ appeared sparingly in Zamenhof's initial vocabulary—primarily in loanwords from Greek and other sources like eĥo (echo) and arĥitekto (architect)—it was retained as an integral part of the standard alphabet despite its limited frequency.[39] During the early 20th century, significant debates arose over ĥ's utility, culminating in the 1907–1908 Ido reform, a splinter language proposed by the International Delegation for the Adoption of an Auxiliary Language to address perceived complexities in Esperanto. Ido reformers eliminated diacritics, replacing ĥ with "k" or "h" to align more closely with natural Romance and Germanic forms; for instance, Esperanto's eĥo became eko, and monaĥo became monako.[40] This proposal was rejected by mainstream Esperantists, who had affirmed the Fundamento's immutability at the 1905 Universal Esperanto Congress in Boulogne-sur-Mer, preserving ĥ's status but highlighting ongoing tensions between tradition and simplification.[5] In the modern era, ĥ's usage has notably declined, with corpus analyses showing it appears in fewer than 0.1% of words, leading to widespread substitution in informal contexts—such as eko for eĥo or arkitekto for arĥitekto—driven by phonetic similarity and ease of expression. The Akademio de Esperanto continues to uphold ĥ as official, permitting ASCII alternatives like "hh" only in technical constraints, while acknowledging its infrequency in declarations on orthography.[41] Discussions in the 2010s, particularly in digital Esperanto communities, speculated on phasing out ĥ to improve typing accessibility on non-specialized keyboards, but no formal reforms have occurred as of 2025, maintaining its place in the language's core structure. As of 2025, the Akademio de Esperanto continues to emphasize orthographic fidelity in official publications. The challenges posed by ĥ's rarity and diacritic form influenced subsequent constructed languages, including Edgar de Wahl's Occidental (1922) and Otto Jespersen's Novial (1928), both of which eschewed diacritics entirely to prioritize typographic simplicity and broader adoption without specialized input methods.[42]References

- https://eo.wikisource.org/wiki/Pa%C4%9Do:Zamenhof_L._L._-_Fundamento_de_Esperanto%2C_1905.djvu/18