Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hashihime

View on Wikipedia

Hashihime (橋姫, "Bridge Princess" or "Bridge Maiden")[1] is a character appearing in Japanese folklore and literature. She first appeared in Japanese Heian literature, initially represented as a woman spending lonely nights waiting for her lover. Later legends depicted her as a guardian spirit of bridges, or alternatively as a fierce kijo (female demon) fueled by jealousy.[2] She is most famously associated with a bridge in Uji.

Origins and Etymology

[edit]The origins of Hashihime beliefs are multifaceted. Primarily, large and ancient bridges were often believed to have a guardian deity, the Hashihime, who protected the bridge from external threats.[2] This may stem from older water deity worship, where pairs of male and female deities were enshrined at bridge crossings.[3]

The common interpretation of Hashihime as intensely jealous may derive from several sources. Local deities often dislike mentions of other places, which, combined with local worshippers' pride, might have been interpreted as jealousy when applied to a female deity.[3] Alternatively, the name itself might involve a pun: hashi (橋, bridge) sounds similar to the classical Japanese word hashi (愛し), meaning "lovely" or "beloved." Thus, "Hashihime" could imply both "Bridge Princess" and "Beloved Maiden," linking the guardian role with themes of love and longing.[2] Legends claim that praising another bridge while on a Hashihime's bridge, or reciting Noh chants about female jealousy (like Aoi no Ue), could invoke her wrath.[3]

While the Hashihime of Uji is the most famous, similar traditions exist for the Nagara Bridge in Osaka (shrine no longer extant) and the Seta no Karahashi bridge in Shiga Prefecture.[4]

In Literature

[edit]Kokin Wakashū

[edit]

Hashihime appears early in Japanese literature, notably in the Kokin Wakashū (ca. 905), in an anonymous poem (Book 14, Love IV, poem #730):

衣を片敷き今宵もや 我を待つらん宇治の橋姫

In waka poetry, Hashihime often embodies pathos and loneliness, waiting for an absent lover, contrasting sharply with her later demonic portrayals.

The Tale of the Heike (Sword Chapter)

[edit]

The most famous legend establishing Hashihime as a jealous demon originates from the "Tsurugi no maki" (Chapter of the Sword). This chapter is found in expanded variant texts of The Tale of the Heike, such as the Genpei Jōsuiki and the Yashirobon manuscript, and also appears in the Taiheiki.[5]

The story is set during the reign of Emperor Saga (809-823). A noblewoman, consumed by jealousy towards a rival, performs a seven-day retreat at Kifune Shrine. She prays to the deity (Kifune Myōjin) to turn her into a living kijo (demoness) to exact revenge. Taking pity, the deity instructs her: "If you truly wish to become a demon, change your appearance and immerse yourself in the rapids of the Uji River for twenty-one days."

She returns to the capital (Heian-kyō), ties her hair into five horns, paints her body red with cinnabar and red lead, and dons an inverted iron tripod (kanawa) on her head, lighting torches on its legs. She also carries a torch lit at both ends in her mouth. In this terrifying guise, she runs south, causing onlookers to die of fright. She immerses herself in the Uji River for 21 days, successfully transforming into the Hashihime demon.

She then proceeds to kill her rival, the rival's family, her former lover's family, and eventually countless innocent people in the capital, changing her form as needed (woman to kill men, man to kill women). Fear grips the city, forcing residents indoors after dusk.

The narrative then jumps forward nearly two centuries to the time of the warrior Minamoto no Yorimitsu (late 10th-early 11th century). Yorimitsu sends his retainer, Watanabe no Tsuna (one of the Four Heavenly Kings), on an errand. Due to the danger, Yorimitsu lends Tsuna his legendary sword, Higekiri. On his return, Tsuna crosses the Ichijō Modoribashi bridge over the Horikawa River (not the Uji Bridge). There, he encounters a beautiful woman who asks for an escort. After Tsuna helps her onto his horse, she reveals her true demonic form, grabs his hair, and attempts to fly him to her lair on Mount Atago. Tsuna reacts quickly, drawing Higekiri and severing the demon's arm. He falls near Kitano Tenmangū shrine, while the demon escapes, leaving her arm behind. The arm, once appearing white, is now black and covered in coarse white hair.

Yorimitsu consults the famous onmyōji Abe no Seimei. Seimei performs rituals to seal the demonic arm, and Tsuna undergoes purification rites for seven days. The sword Higekiri is said to have been renamed Onikiri (鬼切, "Demon Cutter") after this event.

Notably, the legend connects the origin ritual to Uji River/Bridge but depicts the famous encounter at Ichijō Modoribashi in central Kyoto, and involves a significant chronological leap between Emperor Saga's era and Tsuna's lifetime.

The Tale of Genji

[edit]Hashihime's name appears prominently in Murasaki Shikibu's The Tale of Genji (early 11th century).

- It is the title of Chapter 45, "Hashihime" (The Bridge Maiden / The Lady at the Bridge).

- The character is also alluded to several times in waka poems within the novel, often invoking the image of a woman waiting forlornly at the Uji Bridge.[1]

Other Literature

[edit]Hashihime is mentioned in other works like the Taiheiki and the Hashihime Monogatari. The Tale of Genji Museum in Uji features an original short film titled "Hashihime: The Hearts of Women."

Associated Legends and Concepts

[edit]Kanawa (Noh Play)

[edit]The Noh play Kanawa (鉄輪, "The Iron Tripod") dramatizes the demonic transformation legend from the "Tsurugi no maki". The protagonist is a wife abandoned for another woman. She undertakes the ritual (wearing the iron tripod, hence the title) to become a demon and curse the couple. They seek help from Abe no Seimei, who uses katashiro (effigies) to counter the curse. The demoness appears in her terrifying form (using the specific "Hashihime" Noh mask) but is ultimately repelled by Seimei and guardian deities. Watanabe no Tsuna does not appear in this adaptation.[6]

Ushi no toki mairi

[edit]The specific curse ritual performed by the woman in the Hashihime legend—dressing in white, wearing an iron tripod with candles, visiting a shrine at the Hour of the Ox (1-3 AM), and striking a nail into a sacred tree—is considered the archetype for the traditional Japanese curse ritual known as ushi no toki mairi (丑の刻参り, "ox-hour shrine visit").[7] The Kifune Shrine, where Hashihime prayed in the legend, remains famously associated with this practice.

Associated Shrines

[edit]Hashihime Shrine (Uji)

[edit]Located near the Uji Bridge in Kyoto, Hashihime Shrine (橋姫神社, Hashihime-jinja) is popularly associated with the Hashihime of legend. Though officially enshrining Seoritsuhime (a purification goddess often linked to water and bridges),[8] the shrine is widely identified with the jealous Hashihime. While she is venerated as a guardian of the bridge, she is also considered a deity of enkiri – severing unwanted relationships. Due to her legendary jealousy, it is considered taboo for couples, especially newlyweds, to cross the Uji Bridge or visit the shrine together.

Aekuni Hashihime Shrine (Ise)

[edit]A separate shrine, Aekuni Hashihime Shrine (饗土橋姫神社, Aekuni Hashihime-jinja), exists near the Uji Bridge (宇治橋, Uji-bashi – a different bridge with the same phonetic name) that spans the Isuzu River within the Ise Grand Shrine complex in Mie Prefecture. Likely founded later (Kamakura or Muromachi period), it was originally called Ōhashi Hashihime Gozen-sha. "Aekuni" refers to the locality, associated with rituals against plagues. Unlike the Uji Hashihime, this deity has no association with jealousy, demons, or curses, and likely also enshrines Seoritsuhime as a bridge guardian.

In popular culture

[edit]- The shoot 'em up game Touhou Chireiden ~ Subterranean Animism features the character Mizuhashi Parsee as the Stage 2 boss. She is explicitly identified as a Hashihime who guards a bridge connecting the surface world to the underworld and possesses the ability to manipulate jealousy.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Shikibu, Murasaki; Tyler, Royall (2003). The Tale of Genji. Penguin. p. 827. ISBN 978-0-14-243714-8. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Tada, Katsumi (1990). Gensō Sekai no Jūnintachi IV Nippon Hen [Inhabitants of the Fantasy World, Vol. IV: Japan]. Truth In Fantasy (in Japanese). Shin Kigensha. p. 137. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- ^ a b c Noguchi, Hiroshi (1986). "Hashihime" [Bridge Princess]. In Inui, Katsumi; et al. (eds.). Nihon Denki Densetsu Daijiten [Encyclopedia of Japanese Tales and Legends] (in Japanese). Kadokawa Shoten. pp. 709–710. ISBN 978-4-04-031300-9.

- ^ Inada, Atsunobu; Tanaka, Naohiko, eds. (1992). Toriyama Sekien Gazu Hyakki Yagyō [Toriyama Sekien's Illustrated Hyakki Yagyō] (in Japanese). Supervised by Takada Mamoru. Kokusho Kankōkai. p. 116. ISBN 978-4-336-03386-4.

- ^ Note: Standard compilations of The Tale of the Heike often omit the "Tsurugi no maki". See for example: J-TEXTS (Japanese).

- ^ Kato, Eileen (1970). "The Iron Crown (Kanawa)". In Keene, Donald (ed.). Twenty Plays of the Nō Theatre. Columbia University Press. pp. 193–194ff. ISBN 9780231034555.

- ^ Murguia, Salvador Jimenez (2013). "The Cursing Kit of Ushi no Koku Mairi". Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural. 2 (1): 73–91. doi:10.5325/preternature.2.1.0073. JSTOR 10.5325/preternature.2.1.0073. S2CID 141380088.

- ^ 三橋, 健 [in Japanese] (2011). 決定版知れば知るほど面白い! 神道の本 (in Japanese). 西東社. pp. 264–5. ISBN 978-4791618163.

External links

[edit]- Hashihime - The Bridge Princess at hyakumonogatari.com (English).

- The Tale of the Hashihime of Uji at hyakumonogatari.com (English).

- Hashihime (Noh mask from the Nagasawa Shigeharu Noh Mask Collection) (in Japanese)

Hashihime

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Origins

Name and Linguistic Roots

The term "Hashihime" (橋姫) is composed of two kanji characters: 橋 (hashi), meaning "bridge," and 姫 (hime), denoting "princess," "maiden," or "noble woman." This literal breakdown translates to "Bridge Princess" or "Maiden of the Bridge," reflecting its association with bridge-dwelling female spirits in Japanese folklore.[1][3] Some scholars interpret "Hashihime" as a generic designation for female bridge deities, emphasizing its role in denoting protective or liminal entities rather than a specific individual.[3] Additionally, the pronunciation "hashihime" carries a homophonic resonance with "airashi-hime" (愛らしい姫), an archaic form evoking "pretty" or "charming princess," suggesting an underlying connotation of allure tied to ancient linguistic patterns.[4] Linguistically, the term traces its roots to the Heian period (794–1185 CE), where it first emerges in classical poetry and narratives as a metaphor for a bridge-inhabiting spirit symbolizing longing and transience. The earliest documented usage appears in the Kokin Wakashū (古今和歌集), an imperial anthology compiled in 905 CE, specifically in a poem from scroll 14 that references the "Hashihime of Uji" as a poignant image of patient waiting.[4][5] In Heian literature, such as the Genji Monogatari, the name appears as a chapter title evoking poetic themes of longing at bridges, later evolving into supernatural motifs in medieval tales.[4] This usage highlights a shift toward personifying bridges as sentient, feminine entities in waka poetry and tales. Pronunciation remains standardized as "hashihime" (はしひめ) in classical and modern Japanese, with minimal regional dialectal variations documented; however, contextual specificity yields forms like "Uji no Hashihime" (宇治の橋姫), appending "Uji no" to indicate the Uji River bridge locale, a convention rooted in Heian-era geographic naming practices.[1] Etymologically, the term connects to ancient Shinto views of bridges as genkaisen (境界線), or liminal boundaries between the human realm and the divine, where such spaces were guarded by kami (spirits) often anthropomorphized as maidens.[6][7] This linguistic foundation underscores bridges' symbolic role in broader Japanese mythology as thresholds facilitating transitions between worlds.[7]Historical and Mythological Foundations

The origins of Hashihime draw from ancient Shinto practices of bridge worship, where bridges served as liminal spaces consecrated to kami associated with passage, transition, and ritual separation between the human and divine realms.[8] In pre-Heian Japan, such sites were revered for their role in facilitating safe crossings and invoking protective deities against perils of travel or existential divides, a tradition reflected in early mythological narratives of boundary guardians.[8] Scholars have interpreted her as an evolved bridge deity embodying themes of separation and vengeful transition.[3] Hashihime first emerges in 10th-century literature as a symbol of feminine envy and supernatural transformation, rooted in tales of a court lady's desperate pact with riverine deities along the Uji waterway.[9] Her narrative appears poetically in the Kokin wakashū, evoking a woman's longing at the Uji Bridge, which later intensifies into demonic motifs in 12th-century collections like the Konjaku monogatari shū.[8] The demonic transformation legend is detailed in the "Tsurugi no maki" of the Heike monogatari (late 12th–13th century), set during the Heian era under Emperor Saga (r. 809–823), adapting earlier poetic motifs into a vengeful yōkai narrative where a noblewoman seeks otherworldly aid to transcend human limitations.[10] In the Heian-era cultural context, Hashihime's legend mirrors imperial court dynamics, where rigid gender roles confined women to private spheres of influence, amplifying jealousy as a recurring motif in polygamous households and aristocratic narratives.[10] Stories like hers, paralleling the envious spirits in The Tale of Genji, highlight how emotional marginalization could invoke supernatural retribution, serving as cautionary tales against infidelity amid the era's hierarchical marriages and limited female autonomy.[9] This framework positions her not merely as a yōkai but as a mythological critique of courtly envy, blending Shinto ritual with the psychological tensions of Heian society.[8]Characteristics as a Yōkai

Physical Depictions

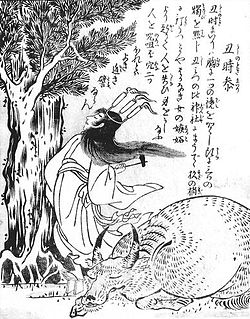

Hashihime is traditionally depicted in Japanese folklore as a fearsome oni-like figure resulting from a woman's transformation driven by jealousy, featuring bright red skin achieved through vermilion dye, hair twisted into five horns, and an iron trivet crown holding three blazing torches.[2] She often appears with additional torches clenched in her teeth, emphasizing her vengeful rage, while her body is adorned in a white robe to evoke demonic ferocity. Depictions vary slightly, with some accounts showing five candles instead of torches.[1] In Edo-period ukiyo-e prints and emaki scrolls, such as those by Toriyama Sekien in his 1779 work Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki, Hashihime is illustrated as a horned demoness lurking beneath bridges, with fangs, flowing disheveled hair, and a shadowy, watery aura that ties her to riverine domains.[4] Variations by artists like Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Okumura Masanobu portray her in dynamic scenes of confrontation, highlighting elongated limbs, claw-like hands, and an overall hybrid form blending human maiden features with oni savagery to convey terror.[2] Symbolic elements in these depictions frequently incorporate fire through the persistent torch motifs, representing the burning intensity of her jealousy, alongside water imagery such as waves or misty bridges to signify her hauntings at crossing points like the Uji River.[1] Post-Heian artistic representations evolved from earlier human-like portrayals of a courtly woman in Heian literature to more hybridized demonic forms by the medieval period, as seen in Heike Monogatari-influenced illustrations where her oni transformation includes an iron crown embedded in her eyebrows and a luminous yet horrifying presence.[4]Powers and Symbolic Associations

Hashihime possesses supernatural abilities rooted in her transformation from a human driven by intense jealousy into a powerful oni, or demon, granting her the capacity to curse unfaithful lovers and induce separations such as divorces or break-ups. In folklore accounts, her vengeful powers manifest as shape-shifting to target victims—appearing as a man to slay women or as a woman to slay men—leading to indiscriminate killings and disappearances, particularly aimed at couples crossing bridges. This demonic strength enables her to attack unfaithful pairs directly, embodying a force capable of severing not only romantic bonds but also broader misfortunes like persistent bad luck.[10][1] Symbolically, Hashihime represents the destructive consequences of unchecked jealousy, or netami, which propels her transformation into an oni, serving as a cautionary figure against infidelity in a polygamous society where women were often marginalized. She embodies the "demon of the heart" (kokoro no oni), illustrating how repressed emotions and personal grudges can erupt into supernatural vengeance, contrasting with male oni's more public, political resentments. As a guardian of long, ancient bridges, she symbolizes the boundary between human and spirit realms, with bridges themselves acting as liminal spaces where human frailties invite otherworldly intervention.[10][1] Despite her primarily vengeful nature, Hashihime exhibits protective aspects in certain folklore traditions, where she is invoked to end toxic relationships or ward off misfortune, positioning her as a goddess of separation who aids in breaking harmful ties. This duality highlights her role in facilitating necessary severances, such as divorces that liberate individuals from suffering, thereby offering a counterbalance to her destructive curses.[1] Her powers are often tied to time-specific rituals, particularly manifesting with heightened potency during the "ox hour" (ushi no toki), from 1 to 3 a.m., a period associated with curse efficacy in Japanese lore, when she is said to appear at sites like Kifune Shrine to amplify her jealous interventions.[1]Literary Appearances

In Heian-Period Poetry

Hashihime first appears in the Heian-period imperial anthology Kokin Wakashū, compiled circa 905 CE under the auspices of Emperor Daigo, where she is evoked as a poignant symbol of longing and isolation. In this collection of waka poems, she embodies the "bridge maiden" (hashihime) of Uji, a figure awaiting her absent lover, reflecting the emotional distances inherent in courtly romance. This early depiction lacks the later demonic transformations, instead aestheticizing her solitude against the backdrop of the Uji River, a site associated with separation in classical imagery.[11] A representative example is the anonymous poem from Book 6 (Love II), numbered 689 in standard editions:samushiro niRendered in English as: "Upon a narrow straw mat, / She spreads her robe— / Tonight, once more, / Will she await me, / The Hashihime of Uji?" This verse imagines the maiden's patient vigil, her robe laid out in anticipation, underscoring the quiet pathos of unrequited devotion without developing a full narrative. Similar Uji River allusions appear sporadically in the anthology's love poems, linking Hashihime to themes of nocturnal yearning and the bridge as a liminal space of emotional parting.[11] In Heian waka, the bridge motif symbolizes profound emotional divides, with Hashihime personifying feminine isolation amid the polygynous dynamics of aristocratic life, where wives often endured rivals and divided affections. Her image captures mono no aware—the gentle sadness of transience—elevating personal envy into a refined courtly sentiment rather than outright malice. These poetic treatments prioritize evocative imagery over storytelling, using Hashihime to explore the vulnerabilities of women in imperial society. The Kokin Wakashū's portrayal of Hashihime laid foundational groundwork for jealousy as a recurring trope in subsequent Heian and early medieval verse, influencing later anthologies like Gosen Wakashū (951 CE) and embedded poems in prose works, where her longing motif recurs to evoke relational strife and desire. This establishment of emotional depth in her character shaped imperial-era poetic conventions, prioritizing subtle pathos over supernatural elements.

koromo katashiki

koyoi mo ya

ware o matsuramu

uji no hashihime