Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

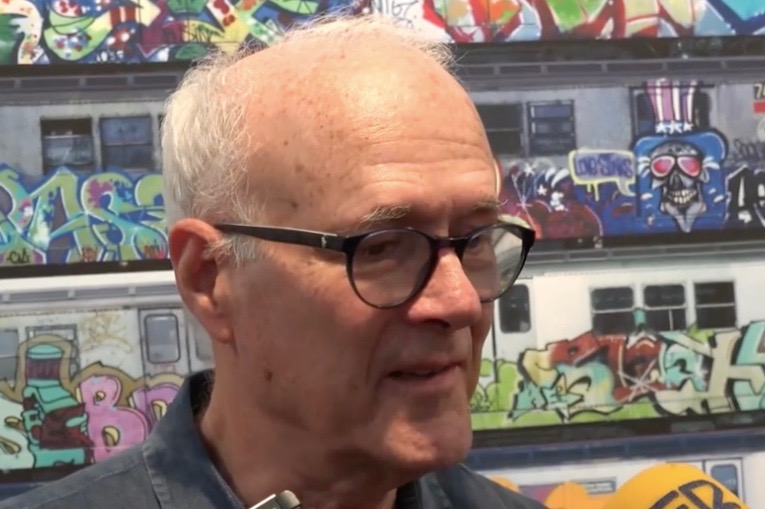

Henry Chalfant

View on WikipediaHenry Chalfant (born January 2, 1940) is an American photographer and videographer most notable for his work on graffiti, breakdance, and hip hop culture.

Key Information

One of Chalfant's prints is held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Education and career

[edit]Chalfant is a graduate of Stanford University, where he majored in classical Greek. Starting out as a sculptor in New York City in the 1970s, Chalfant turned to photography and film to do an in-depth study of hip-hop culture and graffiti art. One of the foremost authorities on New York subway art, and other aspects of urban youth culture, his photographs record hundreds of ephemeral, original art works that have long since vanished.[1]

His photographs have appeared in exhibitions of graffiti art from its early appearances in New York/New Wave at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center to retrospectives such as Art in the Streets at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and City as Canvas: Graffiti Art From the Martin Wong Collection at the Museum of the City of New York, in addition to galleries and museums in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

In 1983, Chalfant co-produced the PBS documentary Style Wars, the seminal documentary about graffiti and hip hop culture.[2] Among Chalfant's other films are Flyin' Cut Sleeves, a documentary about Bronx street gang leaders in the 1970s and Visit Palestine: Ten Days on the West Bank, based on his visit to the occupied territories in 2000. His 2006 documentary From Mambo to Hip Hop: A South Bronx Tale chronicles two generations who grew up on the same blocks of the Bronx, NY, using rhythm as their form of rebellion—for the older generation of the 1950s it was the rhythms of Cuba; for their children of the 1970s it was the rhythms of rap.[3] The film was featured in the Latino Public Broadcasting series Voces in 2006-2007, and won an Alma Award for Best Documentary.

He has co-authored an account of New York graffiti art, Subway Art, and a sequel on the art form's worldwide diffusion, Spraycan Art.

Chalfant has stated his influences are varied:

"In college my mentor was Charles Rowan Beye, the Greek scholar. I really didn't have a mentor for my art work, but I was influenced by great sculptors I admired like David Smith and Eduardo Chillida. For visual anthropology, I was influenced by the ethnographic filmmaker, Jean Rouch."[4]

Chalfant continues to preserve and archive past work, make documentary films, and mentor other filmmakers' work through Public Art Films, a non-profit organization "dedicated to producing films and videos about grassroots cultural expressions."[5]

Henry Chalfant's Big Subway Archive

[edit]On June 29, 2012, Chalfant released Henry Chalfant's Big Subway Archive as a 200-page book. Produced by Chalfant and Max Hergenrother, it is the first volume of a multi-volume archive comprising his entire collection of subway graffiti photographs. The archive series was renamed Henry Chalfant's Graffiti Archive: New York City's Subway Art and Artists in 2013.[6]

The e-books are published by Sleeping Dog Films, which primarily archives the photographer's over 800 photos of New York City Subway graffiti.[7]

Each book in the series concentrates on a particular group or groups of graffiti artists, with an introduction by Chalfant giving background on the time and place in which the artists worked. These passages also contain non-subway-car photos of the artists or their neighborhoods as well as video interviews with the featured artists. The pictures of the subway cars are actually multiple photos overlapped to show the entire length of the subway car at a direct ninety degree angle.

The first three volumes of the series have been released. Volume 1, CYA and TVS published June 29, 2012; CYA stands for "Crazy Young Artists" and TVS stands for "The Vamp Squad." Volume 2, Rolling Thunder Writers and Soul Artists, published December 7, 2012.[8] Volume 3, TC5 featuring Blade, published July 1, 2013; "TC5" stands for "The Crazy Five" or "The Cool Five."[9]

The series has received generally positive critical support and has generated mild controversy for some interview material, such as graffiti artist Lady Pink's assertion that "The graffiti movement has become a greater thing than the Renaissance."[10] The series also sheds new light on some historical graffiti feuds such as Seen TC5 versus Seen UA.[11]

Exhibitions

[edit]- A-Dieci Gallery (1970), Padua

- 14 Sculptors Gallery (1973), New York

- Sculptors Guild, Lever House (1974), New York

- Three Rivers Arts Festival (1977), Pittsburgh

- O.I.A. (1977) Battery Park, New York

- 55 Mercer Gallery (1978), New York

- New York/New Wave (1981) P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, New York

- Sculptors Guild (1981) Bronx Botanical Garden, New York

- Elaine Benson Gallery (1981) Bridgehampton, New York

- The Comic Art Show (1983) Whitney Downtown, New York

- Content, a Contemporary Focus 1974-1984 (1984) Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C.

- Since the Harlem Renaissance: 50 Years of Afro-American Art (1985) Bucknell University, Lewisburg

- Hip Hop: A Cultural Expression (1999) Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Cleveland

- Art of the American Century Part ll (1999) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

- Urban Mythologies (1999) Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York

- Hip Hop (2000) Museum of Pop Culture, Seattle

- Born in the Streets (2009) Fondation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain, Paris

- Art in the Streets (2011) Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

- Moving Murals (2014) City Lore Gallery, New York

- City as Canvas: Graffiti Art From the Martin Wong Collection (2014) Museum of the City of New York

- 1980 (2016) Eric Firestone Loft, New York

- Art Is Not A Crime 1977-1987 (2018) CEART Fuenlabrada, Madrid[12]

- Henry Chalfant: Art vs. Transit, 1977-1987 (2019) Bronx Museum, New York [13]

Chalfant's solo exhibitions also include[14] Maharishi (2002), London; Prosper (2002), Tokyo; Galerie Speerstra (2003, 2006), Paris; Iguapop (2004), Barcelona; Montana Colors (2006), Barcelona; and Cox 18 (2006), Milano.

Personal life

[edit]He married actress Kathleen Chalfant (née Bishop) in 1966. They have two children: David Chalfant, a record producer and bass player for the folk-rock band The Nields; and Andromache Chalfant, a set designer. The Chalfants live in Brooklyn Heights.[15]

Collections

[edit]Chalfant's work is held in the following public collection:

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City: 1 print ("Children of the Grave, Part II")[16]

References

[edit]- ^ "Henry Chalfant Biography". artnet.com. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Harder, Jeff (14 November 2014). "Inside the '80s Graffiti Doc Style Wars". Esquire. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (14 September 2006). "Mambo and Hip-Hop: Two Bronx Sounds, Once Sense of Dignity". New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Bravo, Vee (1998). "Henry Chalfant: Granddaddy of the Graff Flik". Stress Magazine. 13.

- ^ "Style Wars Auction". obeygiant.com. 27 May 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ iTunes Henry Chalfant's Graffiti Archive Vol. 1

- ^ "HCGA Volume 1". Apple Computer. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "HCGA Volume 2". Apple Computer. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "HCGA Volume 3". Apple Computer. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "Graffiti:Bigger than the Renaissance". Deadly Buda. 22 March 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Gonzalez, David (14 December 2012). "Art, Elevated: Henry Chalfant's Archives". New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "HENRY CHALFANT. "ART IS NOT A CRIME, 1977 – 1987" Del 27 de septiembre al 18 de noviembre de 2018 SALAS A y B". 5 November 2018. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ^ "Henry Chalfant: "Art vs. Transit, 1977-1987" September 25, 2019 to March 8, 2020". 25 September 2019.

- ^ "Henry Chalfant". Concrete to Data. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Cardin, Kathryn (26 January 2015). "Award-winning actress, new to Brooklyn Heights, falls in love with the place". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "Children of the Grave, Part II". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2018-11-12.

External links

[edit]Henry Chalfant

View on GrokipediaHenry Chalfant (born January 2, 1940) is an American photographer, filmmaker, and sculptor renowned for his extensive documentation of New York City subway graffiti and the nascent hip-hop culture during the late 1970s and early 1980s.[1] Originally trained as a sculptor after graduating from Stanford University, Chalfant relocated to New York in 1973 and shifted his focus to photography upon encountering the vibrant, illicit street art adorning subway cars.[1] His work captured the ephemeral nature of this underground movement, preserving images of whole-train masterpieces by pioneering graffiti writers such as Dondi, Futura, and Lee Quiñones before they were buffed or painted over by transit authorities.[2] Chalfant's innovative technique involved taking sequential photographs from elevated platforms to composite full views of graffiti-covered trains, resulting in an archive exceeding 1,500 images that form a visual record of urban youth expression.[2] He co-authored the seminal book Subway Art with Martha Cooper in 1984, which provided the first comprehensive photographic survey of the graffiti phenomenon and influenced its global spread.[3] Additionally, as co-producer and cinematographer of the 1983 PBS documentary Style Wars, Chalfant offered an unflinching portrayal of graffiti artists, breakdancers, and DJs, earning the film the Grand Prize at the Sundance Film Festival and cementing its status as a foundational hip-hop document.[1] Beyond graffiti, Chalfant's oeuvre includes books like Spraycan Art (1987) and Training Days (2015), as well as films such as From Mambo to Hip Hop (2006), which earned an Alma Award for its exploration of South Bronx cultural evolution.[1] His photographs are held in prestigious collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Carnegie Institute, and have been featured in major retrospectives, underscoring his role as a pivotal archivist of street culture's raw, unfiltered vitality.[3]