Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Brooklyn

View on Wikipedia

Brooklyn is the most populous of the five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located at the westernmost end of Long Island and formerly an independent city, Brooklyn shares a land border with the borough and county of Queens. It has several bridge and tunnel connections to the borough of Manhattan, across the East River, most famously, the architecturally significant Brooklyn Bridge, and is connected to Staten Island by way of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge.

Key Information

The borough, as Kings County, at 37,339.9 inhabitants per square mile (14,417.0/km2), is the second most densely populated county in the U.S. after Manhattan (New York County), and the most populous county in the state, as of 2022.[7] In the 2020 United States census,[3] the population stood at 2,736,074.[8][9][10] Had Brooklyn remained an independent city on Long Island, it would now be the fourth most populous American city after the rest of New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, while ahead of Houston.[10] With a land area of 69.38 square miles (179.7 km2) and a water area of 27.48 square miles (71.2 km2), Kings County, one of the twelve original counties established under British rule in 1683 in the then-province of New York, is the state of New York's fourth-smallest county by land area and third smallest by total area.[11]

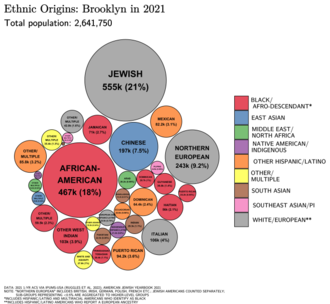

Brooklyn, named after the Dutch town of Breukelen in the Netherlands, was founded by the Dutch in the 17th century and grew into a busy port city on New York Harbor by the 19th century. On January 1, 1898, after a long political campaign and public-relations battle during the 1890s and despite opposition from Brooklyn residents, Brooklyn was consolidated in and annexed, along with other areas, to form the current five-borough structure of New York City in accordance to the new municipal charter of Greater New York.[12] The borough continues to maintain some distinct culture. Many Brooklyn neighborhoods are ethnic enclaves. With Jews forming around a fifth of its population, the borough has been described as one of the main global hubs for Jewish culture.[13] Brooklyn's official motto, displayed on the borough seal and flag, is Eendraght Maeckt Maght, which translates from early modern Dutch as 'Unity makes strength'.[14]

Educational institutions in Brooklyn include the City University of New York's Brooklyn College, Medgar Evers College, and College of Technology, as well as, Pratt Institute, Long Island University, and the New York University Tandon School of Engineering. In sports, basketball's Brooklyn Nets, and New York Liberty play at the Barclays Center. In the first decades of the 21st century, Brooklyn has experienced a renaissance as a destination for hipsters,[15] with concomitant gentrification, dramatic house-price increases, and a decrease in housing affordability.[16] Some new developments are required to include affordable housing units.[17] Since the 2010s, parts of Brooklyn have evolved into a hub of entrepreneurship, high-technology startup firms,[18][19] postmodern art,[20] and design.[19]

Toponymy

[edit]The name Brooklyn is derived from the original Dutch town of Breukelen. The oldest mention of the settlement in the Netherlands is in a charter of 953 by Holy Roman Emperor Otto I as Broecklede.[21] This form is made up of the words broeck, meaning bog or marshland, and lede, meaning small (dug) water stream, specifically in peat areas.[22] Breuckelen on the American continent was established in 1646, and the name first appeared in print in 1663.[23][24][25]

Over the past two millennia, the name of the ancient town in Holland has been Bracola, Broccke, Brocckede, Broiclede, Brocklandia, Broekclen, Broikelen, Breuckelen, and finally Breukelen.[26] The New Amsterdam settlement of Breuckelen also went through many spelling variations, including Breucklyn, Breuckland, Brucklyn, Broucklyn, Brookland, Brockland, Brocklin, and Brookline/Brook-line. There have been so many variations of the name that its origin has been debated; some have claimed breuckelen means "broken land".[27] The current name, however, is the one that best reflects its meaning.[28][29]

The county's name, Kings County, was named after King Charles II of England, who ruled from 1660 to 1685.

History

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Long Island |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Regions |

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

The history of European settlement in Brooklyn spans more than 350 years. The settlement began in the 17th century as the small Dutch-founded town of "Breuckelen" on the East River shore of Long Island, grew to be a sizeable city in the 19th century and was consolidated in 1898 with New York City (then confined to Manhattan and the Bronx), the remaining rural areas of Kings County, and the largely rural areas of Queens and Staten Island, to form the modern City of New York.

Colonial era

[edit]New Netherland

[edit]The Dutch were the first Europeans to settle Long Island's western edge, which was then largely inhabited by the Lenape, an Algonquian-speaking American Indian tribe often referred to in European documents by a variation of the place name "Canarsie". Bands were associated with place names, but the colonists thought their names represented different tribes. The Breuckelen settlement was named after Breukelen in the Netherlands; it was part of New Netherland. The Dutch West India Company lost little time in chartering the six original parishes (listed here by their later English town names):[30]

- Gravesend: in 1645, settled under Dutch patent by English followers of Anabaptist Deborah Moody, named for 's-Gravenzande, Netherlands, or Gravesend, England;

- Brooklyn Heights: chartered as Breuckelen in 1646, after the town now spelled Breukelen, Netherlands. Breuckelen was along Fulton Street (now Fulton Mall) between Hoyt Street and Smith Street (according to H. Stiles and P. Ross). Brooklyn Heights, or Clover Hill, is where the village of Brooklyn was founded in 1816;

- Flatlands: chartered as Nieuw Amersfoort in 1647;

- Flatbush: chartered as Midwout in 1652;

- Nieuw Utrecht in 1652, named after the city of Utrecht, Netherlands; and

- Bushwick: chartered as Boswijck in 1661.

A dining table from the Dutch village of Brooklyn, c. 1664, in The Brooklyn Museum

The colony's capital of New Amsterdam, across the East River, obtained its charter in 1653. The neighborhood of Marine Park was home to North America's first tide mill. It was built by the Dutch, and the foundation can be seen today. But the area was not formally settled as a town. Many incidents and documents relating to this period are in Gabriel Furman's 1824 compilation.[31]

Province of New York

[edit]

Present-day Brooklyn left Dutch hands after the English conquest of New Netherland in 1664, which sparked the Second Anglo-Dutch War. New Netherland was taken in a naval action, and the English renamed the new capture for their naval commander, James, Duke of York, brother of the then monarch King Charles II and future king himself as King James II. Brooklyn became a part of the West Riding of York Shire in the Province of New York, one of the Middle Colonies in England's North American colonies.

On November 1, 1683, Kings County was partitioned from the West Riding of York Shire, containing the six old Dutch towns on southwestern Long Island,[32] as one of the "original twelve counties". This tract of land was recognized as a political entity for the first time, and the municipal groundwork was laid for a later expansive idea of a Brooklyn identity.

Lacking the patroon and tenant farmer system established along the Hudson River Valley, this agricultural county unusually came to have one of the highest percentages of slaves among the population in the "Original Thirteen Colonies" along the Atlantic Ocean eastern coast of North America.[33]

Revolutionary War

[edit]

On August 27, 1776, the Battle of Long Island (also known as the 'Battle of Brooklyn') was fought, the first major engagement fought in the American Revolutionary War after independence was declared, and the largest of the entire conflict. British troops forced the Continental Army under George Washington off the heights near the modern sites of Green-Wood Cemetery, Prospect Park, and Grand Army Plaza.[34]

Washington, viewing particularly fierce fighting at the Gowanus Creek and Old Stone House from atop a hill near the west end of present-day Atlantic Avenue, was reported to have emotionally exclaimed: "What brave men I must this day lose!".[34]

The fortified American positions at Brooklyn Heights consequently became untenable and were evacuated a few days later, leaving the British in control of New York Harbor. While Washington's defeat on the battlefield cast early doubts on his ability as the commander, the tactical withdrawal of all his troops and supplies across the East River in a single night is now seen by historians as one of his most brilliant triumphs.[34]

The British controlled the surrounding region for the duration of the war, as New York City was soon occupied and became their military and political base of operations in British-held North America for the remainder of the conflict. The Patriot residents largely fled or changed their political sentiments, and afterward the British generally enjoyed a dominant Loyalist sentiment from the residents in Kings County who did not evacuate, though the region was also the center of the fledgling—and largely successful—Patriot intelligence network, headed by Washington himself.

The British set up a system of prison ships off the coast of Brooklyn in Wallabout Bay. More American prisoners of war died on these prison ships than were killed in action on all the battlefield engagements of the war combined. One result of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 was the evacuation of the British from New York City, which was celebrated by New Yorkers into the 20th century.

Post-independence era

[edit]Urbanization

[edit]

The first half of the 19th century saw the beginning of the development of urban areas on the economically strategic East River shore of Kings County, facing the adolescent City of New York confined to Manhattan Island. The New York Navy Yard operated in Wallabout Bay (border between Fort Greene and Williamsburg) during the 19th century and two-thirds of the 20th century.

The first center of urbanization sprang up in the Town of Brooklyn, directly across from Lower Manhattan, which saw the incorporation of the Village of Brooklyn in 1816. Reliable steam ferry service across the East River to Fulton Landing converted Brooklyn Heights into a commuter town for Wall Street. Ferry Road to Jamaica Pass became Fulton Street to East New York. Town and Village were combined to form the first, kernel incarnation of the City of Brooklyn in 1834.

In a parallel development, the Town of Bushwick, farther up the river, saw the incorporation of the Village of Williamsburgh in 1827, which separated as the Town of Williamsburgh in 1840 and formed the short-lived City of Williamsburgh in 1851. Industrial deconcentration in the mid-century was bringing shipbuilding and other manufacturing to the northern part of the county. Each of the two cities and six towns in Kings County remained independent municipalities and purposely created non-aligning street grids with different naming systems.

However, the East River shore was growing too fast for the three-year-old infant City of Williamsburg; it, along with its Town of Bushwick hinterland, was subsumed within a greater City of Brooklyn in 1855, subsequently dropping the 'h' from its name.[35]

By 1841, with the appearance of The Brooklyn Eagle, and Kings County Democrat published by Alfred G. Stevens, the growing city across the East River from Manhattan was producing its own prominent newspaper.[36] It later became the most popular and highest circulation afternoon paper in America.[citation needed] The publisher changed to L. Van Anden on April 19, 1842,[37] and the paper was renamed The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and Kings County Democrat on June 1, 1846.[38] On May 14, 1849, the name was shortened to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle;[39] on September 5, 1938, it was further shortened to Brooklyn Eagle.[40] The establishment of the paper in the 1840s helped develop a separate identity for Brooklynites over the next century. The borough's soon-to-be-famous National League baseball team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, also assisted with this. Both major institutions were lost in the 1950s: the paper closed in 1955 after unsuccessful attempts at a sale following a reporters' strike, and the baseball team decamped for Los Angeles in a realignment of Major League Baseball in 1957.

Agitation against Southern slavery was stronger in Brooklyn than in New York,[41] and under Republican leadership, the city was fervent in the Union cause in the Civil War. After the war the Henry Ward Beecher Monument was built downtown to honor a famous local abolitionist. A great victory arch was built at what was then the south end of town to celebrate the armed forces; this place is now called Grand Army Plaza.

The number of people living in Brooklyn grew rapidly early in the 19th century. There were 4,402 by 1810, 7,175 in 1820 and 15,396 by 1830.[42] The city's population was 25,000 in 1834, but the police department comprised only 12 men on the day shift and another 12 on the night shift. Every time a rash of burglaries broke out, officials blamed burglars from New York City. Finally, in 1855, a modern police force was created, employing 150 men. Voters complained of inadequate protection and excessive costs. In 1857, the state legislature merged the Brooklyn force with that of New York City.[43]

Civil War

[edit]Fervent in the Union cause, the city of Brooklyn played a major role in supplying troops and materiel for the American Civil War. The best-known regiment to be sent off to war from the city was the 14th Brooklyn "Red Legged Devils". They fought from 1861 to 1864, wore red the entire war, and were the only regiment named after a city. President Abraham Lincoln called them into service, making them part of a handful of three-year enlisted soldiers in April 1861. Unlike other regiments during the American Civil War, the 14th wore a uniform inspired by the French Chasseurs, a light infantry used for quick assaults.

As a seaport and a manufacturing center, Brooklyn was well prepared to contribute to the Union's strengths in shipping and manufacturing. The two combined in shipbuilding; the ironclad Monitor was built in Brooklyn.

Twin city

[edit]Brooklyn is referred to as the twin city of New York in the 1883 poem, "The New Colossus" by Emma Lazarus, which appears on a plaque inside the Statue of Liberty. The poem calls New York Harbor "the air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame". As a twin city to New York, it played a role in national affairs that was later overshadowed by decades of subordination by its old partner and rival.

During this period, the affluent, contiguous districts of Fort Greene and Clinton Hill (then characterized collectively as The Hill) were home to such notable figures as Astral Oil Works founder Charles Pratt and his children, including local civic leader Charles Millard Pratt; Theosophical Society co-founder William Quan Judge; and Pfizer co-founders Charles Pfizer and Charles F. Erhart. Brooklyn Heights remained one of the New York metropolitan area's most august patrician redoubts into the early 20th century under the aegis of such figures as abolitionist clergyman Henry Ward Beecher, Congregationalist theologians Lyman Abbott and Newell Dwight Hillis (who followed Beecher as the second and third pastors of Plymouth Church, respectively), financier John Jay Pierrepont (a grandson of founding Heights resident Hezekiah Pierrepont), banker/art collector David Leavitt, educator/politician Seth Low, merchant/banker Horace Brigham Claflin, attorney William Cary Sanger (who served for two years as United States Assistant Secretary of War under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt) and publisher Alfred Smith Barnes. Contiguous to the Heights, the less exclusive South Brooklyn was home to longtime civic leader James S. T. Stranahan, who became known (often derisively) as the "Baron Haussmann of Brooklyn" for championing Prospect Park and other public works.

Economic growth continued, propelled by immigration and industrialization, and Brooklyn established itself as the third-most populous American city for much of the 19th century. The waterfront from Gowanus to Greenpoint was developed with piers and factories. Industrial access to the waterfront was improved by the Gowanus Canal and the canalized Newtown Creek. USS Monitor was the most famous product of the large and growing shipbuilding industry of Williamsburg. After the Civil War, trolley lines and other transport brought urban sprawl beyond Prospect Park (completed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1873 and widely heralded as an improvement upon the earlier Central Park) into the center of the county, as evinced by gradual settlement in the comparatively rustic villages of Windsor Terrace and Kensington in the Town of Flatbush. By century's end, Dean Alvord's Prospect Park South development (adjacent to the village of Flatbush) would serve as the template for contemporaneous "Victorian Flatbush" micro-neighborhoods and the post-consolidation emergence of outlying districts, such as Midwood and Marine Park. Along with Oak Park, Illinois, it also presaged the automobile and commuter rail-driven vogue for more remote prewar suburban communities, such as Garden City, New York and Montclair, New Jersey.

The rapidly growing population needed more water, so the City built centralized waterworks, including the Ridgewood Reservoir. The municipal Police Department, however, was abolished in 1854 in favor of a Metropolitan force covering also New York and Westchester Counties. In 1865 the Brooklyn Fire Department (BFD) also gave way to the new Metropolitan Fire District.

Throughout this period the peripheral towns of Kings County, far from Manhattan and even from urban Brooklyn, maintained their rustic independence. The only municipal change seen was the secession of the eastern section of the Town of Flatbush as the Town of New Lots in 1852. The building of rail links such as the Brighton Beach Line in 1878 heralded the end of this isolation.

Sports in Brooklyn became a business. The Brooklyn Bridegrooms played professional baseball at Washington Park in the convenient suburb of Park Slope and elsewhere. Early in the next century, under their new name of Brooklyn Dodgers, they brought baseball to Ebbets Field, beyond Prospect Park. Racetracks, amusement parks, and beach resorts opened in Brighton Beach, Coney Island, and elsewhere in the southern part of the county.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the City of Brooklyn experienced its final, explosive growth spurt. Park Slope was rapidly urbanized, with its eastern summit soon emerging as the city's third "Gold Coast" district alongside Brooklyn Heights and The Hill; notable residents of the era included American Chicle Company co-founder Thomas Adams Jr. and New York Central Railroad executive Clinton L. Rossiter. East of The Hill, Bedford-Stuyvesant coalesced as an upper middle class enclave for lawyers, shopkeepers, and merchants of German and Irish descent (notably exemplified by John C. Kelley, a water meter magnate and close friend of President Grover Cleveland), with nearby Crown Heights gradually fulfilling an analogous role for the city's Jewish population as development continued through the early 20th century. Northeast of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Bushwick (by now a working class, predominantly German district) established a considerable brewery industry; the so-called "Brewer's Row" encompassed 14 breweries operating in a 14-block area in 1890. On the southwestern waterfront of Kings County, railroads and industrialization spread to Sunset Park (then coterminous with the city's sprawling, sparsely populated Eighth Ward) and adjacent Bay Ridge (hitherto a resort-like subsection of the Town of New Utrecht). Within a decade, the city had annexed the Town of New Lots in 1886; the Towns of Flatbush, Gravesend and New Utrecht in 1894; and the Town of Flatlands in 1896. Brooklyn had reached its natural municipal boundaries at the ends of Kings County.

Seth Low as mayor

[edit]Low's time in office from 1882 to 1885 was marked by a number of reforms:[44]

- Secured a degree of "home rule" of the city. Previously, the State Government dictated city policies, hiring, salaries, and other affairs. Low managed to secure an unofficial veto over all Brooklyn bills in the State Assembly.

- Instituted a number of educational reforms. He was the first to integrate Brooklyn schools. He introduced free textbooks for all students, not just those who had taken a pauper's oath. He instituted a competitive examination for hiring teachers, instead of giving teaching jobs to pay political debts. He set aside $430,000 (equivalent to $14,010,586 in 2024) for the construction of new schools to accommodate 10,000 new students.

- Introduced Civil Service Code to all city employees, eliminating patronage jobs.

- German Americans wanted to enjoy their local beer gardens on the Sabbath, in violation of state "dry" laws and the demands of local puritanical clergy. Low's compromise solution was that saloons could stay open as long as they were orderly. At the first sign of rowdiness, they would be closed.

- Served as a member of the board of the New York Bridge Company, the company that built the Brooklyn Bridge, and led an unsuccessful effort to remove Washington Roebling as the chief engineer on that project.[45]

- Raised the tax rate from 2.33% of $100 assessed valuation in 1881 to 2.59% in 1883.[44] He also went after property owners who had not paid back taxes. This increase in city revenue enabled him to reduce the city's debt and increase services. However, raising taxes proved extremely unpopular.

Mayors of the City of Brooklyn

[edit]Brooklyn elected a mayor from 1834 until 1898, after which it was consolidated into the City of Greater New York, whose own second mayor (1902–1903), Seth Low, had been Mayor of Brooklyn from 1882 to 1885. Since 1898, Brooklyn has, in place of a separate mayor, elected a Borough President.

| Mayor | Start year | End year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| George Hall | Democratic-Republican | 1834 | 1834 | |

| Jonathan Trotter | Democratic | 1835 | 1836 | |

| Jeremiah Johnson | Whig | 1837 | 1838 | |

| Cyrus P. Smith | Whig | 1839 | 1841 | |

| Henry C. Murphy | Democratic | 1842 | 1842 | |

| Joseph Sprague | Democratic | 1843 | 1844 | |

| Thomas G. Talmage | Democratic | 1845 | 1845 | |

| Francis B. Stryker | Whig | 1846 | 1848 | |

| Edward Copland | Whig | 1849 | 1849 | |

| Samuel Smith | Democratic | 1850 | 1850 | |

| Conklin Brush | Whig | 1851 | 1852 | |

| Edward A. Lambert | Democratic | 1853 | 1854 | |

| George Hall | Know Nothing | 1855 | 1856 | |

| Samuel S. Powell | Democratic | 1857 | 1860 | |

| Martin Kalbfleisch | Democratic | 1861 | 1863 | |

| Alfred M. Wood | Republican | 1864 | 1865 | |

| Samuel Booth | Republican | 1866 | 1867 | |

| Martin Kalbfleisch | Democratic | 1868 | 1871 | |

| Samuel S. Powell | Democratic | 1872 | 1873 | |

| John W. Hunter | Democratic | 1874 | 1875 | |

| Frederick A. Schroeder | Republican | 1876 | 1877 | |

| James Howell | Democratic | 1878 | 1881 | |

| Seth Low | Republican | 1882 | 1885 | |

| Daniel D. Whitney | Democratic | 1886 | 1887 | |

| Alfred C. Chapin | Democratic | 1888 | 1891 | |

| David A. Boody | Democratic | 1892 | 1893 | |

| Charles A. Schieren | Republican | 1894 | 1895 | |

| Frederick W. Wurster | Republican | 1896 | 1897 |

New York City borough

[edit]

In 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was completed, transportation to Manhattan was no longer by water only, and the City of Brooklyn's ties to the City of New York were strengthened.

The question became whether Brooklyn was prepared to engage in the still-grander process of consolidation then developing throughout the region, whether to join with the county of Richmond and the western portion of Queens County, and the county of New York, which by then already included the Bronx, to form the five boroughs of a united City of New York. Andrew Haswell Green and other progressives said yes, and eventually, they prevailed against the Daily Eagle and other conservative forces. In 1894, residents of Brooklyn and the other counties voted by a slight majority to merge, effective in 1898.[47]

Kings County retained its status as one of New York State's counties, but the loss of Brooklyn's separate identity as a city was met with consternation by some residents at the time. Many newspapers of the day called the merger the "Great Mistake of 1898".[48]

Geography

[edit]

Brooklyn is 97 square miles (250 km2) in area, of which 71 square miles (180 km2) is land (73%), and 26 square miles (67 km2) is water (27%); the borough is the second-largest by land area among the New York City's boroughs. However, Kings County, coterminous with Brooklyn, is New York State's fourth-smallest county by land area and third-smallest by total area.[9] Brooklyn lies at the southwestern end of Long Island, and the borough's western border constitutes the island's western tip.

Brooklyn's water borders are extensive and varied, including Jamaica Bay; the Atlantic Ocean; The Narrows, separating Brooklyn from the borough of Staten Island in New York City and crossed by the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge; Upper New York Bay, separating Brooklyn from Jersey City and Bayonne in the U.S. state of New Jersey; and the East River, separating Brooklyn from the borough of Manhattan in New York City and traversed by the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, and numerous routes of the New York City Subway. To the east of Brooklyn lies the borough of Queens, which contains John F. Kennedy International Airport in that borough's Jamaica neighborhood, approximately two miles from the border of Brooklyn's East New York neighborhood.

Climate

[edit]Under the Köppen climate classification, Brooklyn experiences a humid subtropical climate (Cfa),[49] with partial shielding from the Appalachian Mountains and moderating influences from the Atlantic Ocean. Brooklyn receives plentiful precipitation all year round, with nearly 50 in (1,300 mm) yearly. The area averages 234 days with at least some sunshine annually, and averages 57% of possible sunshine annually, accumulating 2,535 hours of sunshine per annum.[50] Brooklyn lies in the USDA plant hardiness zone 7b.[51]

| Climate data for JFK Airport, New York (normals 1981–2010,[52] extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

71 (22) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

90 (32) |

77 (25) |

75 (24) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.8 (13.8) |

57.9 (14.4) |

68.5 (20.3) |

78.1 (25.6) |

84.9 (29.4) |

92.1 (33.4) |

94.5 (34.7) |

92.7 (33.7) |

87.4 (30.8) |

78.0 (25.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

96.6 (35.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.1 (3.9) |

41.8 (5.4) |

49.0 (9.4) |

59.0 (15.0) |

68.5 (20.3) |

78.0 (25.6) |

83.2 (28.4) |

81.9 (27.7) |

75.3 (24.1) |

64.5 (18.1) |

54.3 (12.4) |

44.0 (6.7) |

61.6 (16.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.3 (−3.2) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

34.2 (1.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

52.8 (11.6) |

62.8 (17.1) |

68.5 (20.3) |

67.8 (19.9) |

60.8 (16.0) |

49.6 (9.8) |

40.7 (4.8) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.8 (−12.3) |

13.4 (−10.3) |

19.1 (−7.2) |

32.6 (0.3) |

42.6 (5.9) |

52.7 (11.5) |

60.7 (15.9) |

58.6 (14.8) |

49.2 (9.6) |

37.6 (3.1) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

16.3 (−8.7) |

7.5 (−13.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

−2 (−19) |

4 (−16) |

20 (−7) |

34 (1) |

45 (7) |

55 (13) |

46 (8) |

40 (4) |

30 (−1) |

19 (−7) |

2 (−17) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.16 (80) |

2.59 (66) |

3.78 (96) |

3.87 (98) |

3.94 (100) |

3.86 (98) |

4.08 (104) |

3.68 (93) |

3.50 (89) |

3.62 (92) |

3.30 (84) |

3.39 (86) |

42.77 (1,086) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.3 (16) |

8.3 (21) |

3.5 (8.9) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

4.7 (12) |

23.8 (60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 10.5 | 9.6 | 11.0 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 10.7 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 10.6 | 119.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 inch) | 4.6 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 13.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.9 | 64.4 | 63.4 | 64.1 | 69.5 | 71.5 | 71.4 | 71.7 | 71.9 | 69.1 | 67.9 | 66.3 | 68.0 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity 1961–1990)[53][54][55] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Brooklyn, New York City (Avenue V) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.7 (4.3) |

42.4 (5.8) |

49.7 (9.8) |

60.5 (15.8) |

70.5 (21.4) |

79.3 (26.3) |

84.8 (29.3) |

83.3 (28.5) |

76.5 (24.7) |

65.0 (18.3) |

54.3 (12.4) |

44.5 (6.9) |

62.5 (16.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 27.5 (−2.5) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

35.2 (1.8) |

44.8 (7.1) |

54.4 (12.4) |

64.0 (17.8) |

70.3 (21.3) |

68.9 (20.5) |

62.4 (16.9) |

51.2 (10.7) |

41.4 (5.2) |

33.2 (0.7) |

48.5 (9.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.53 (90) |

2.97 (75) |

4.37 (111) |

3.85 (98) |

4.03 (102) |

4.44 (113) |

4.85 (123) |

3.92 (100) |

3.92 (100) |

4.02 (102) |

3.23 (82) |

4.00 (102) |

47.13 (1,197) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.5 (17) |

8.5 (22) |

4.4 (11) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

4.3 (11) |

24.5 (62) |

| Source: NOAA[56] | |||||||||||||

Boroughscape

[edit]Neighborhoods

[edit]

Brooklyn's neighborhoods are dynamic in ethnic composition. For example, the early to mid-20th century, Brownsville had a majority of Jewish residents; since the 1970s it has been majority African American. Midwood during the early 20th century was filled with ethnic Irish, then filled with Jewish residents for nearly 50 years, and is slowly becoming a Pakistani enclave. Brooklyn's most populous racial group, white, declined from 97.2% in 1930 to 46.9% by 1990.[57]

The borough attracts people previously living in other cities in the United States. Of these, most come from Chicago, Detroit, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston, Cincinnati, and Seattle.[58][59][60][61][62][63][64]

Community diversity

[edit]

Given New York City's role as a crossroads for immigration from around the world, Brooklyn has evolved a globally cosmopolitan ambiance of its own, demonstrating a robust and growing demographic and cultural diversity with respect to metrics including nationality, religion, race, and domiciliary partnership. In 2010, 51.6% of the population was counted as members of religious congregations.[65] In 2014, there were 914 religious organizations in Brooklyn, the 10th most of all counties in the nation.[66] Brooklyn contains dozens of distinct neighborhoods representing many of the major culturally identified groups found within New York City. Among the most prominent are listed below:

Jewish American

[edit]

Over 600,000 Jews, particularly Orthodox and Hasidic Jews, have become concentrated in such historically Jewish areas as Borough Park, Williamsburg, and Midwood, where there are many yeshivas, synagogues, and kosher restaurants, as well as a variety of Jewish businesses. Adjacent to Borough Park, the Kensington area housed a significant population of Conservative Jews (under the aegis of such nationally prominent midcentury rabbis as Jacob Bosniak and Abraham Heller)[67] when it was still considered to be a subsection of Flatbush; many of their defunct facilities have been repurposed to serve extensions of the Borough Park Hasidic community. Other notable religious Jewish neighborhoods with a longstanding cultural lineage include Canarsie, Sea Gate, and Crown Heights, home to the Chabad world headquarters. Neighborhoods with largely defunct yet historically notable Jewish populations include central Flatbush, East Flatbush, Brownsville, East New York, Bensonhurst and Sheepshead Bay (particularly its Madison subsection). Many hospitals in Brooklyn were started by Jewish charities, including Maimonides Medical Center in Borough Park and Brookdale Hospital in East Flatbush.[68][69]

According to the American Jewish Population Project in 2020, Brooklyn was home to over 480,000 Jews.[70] In 2023, the UJA-Federation of New York estimated that Brooklyn is home to 462,000 Jews, a large decrease compared to the 561,000 estimated in 2011.[71]

The predominantly Jewish, Crown Heights (and later East Flatbush)-based Madison Democratic Club served as the borough's primary "clubhouse" political venue for decades until the ascendancy of Meade Esposito's rival, Canarsie-based Thomas Jefferson Democratic Club in the 1960s and 1970s, playing an integral role in the rise of such figures as Speaker of the New York State Assembly Irwin Steingut; his son, fellow Speaker Stanley Steingut; New York City Mayor Abraham Beame; real estate developer Fred Trump; Democratic district leader Beadie Markowitz; and political fixer Abraham "Bunny" Lindenbaum.

Many non-Orthodox Jews (ranging from observant members of various denominations to atheists of Jewish cultural heritage) are concentrated in Ditmas Park and Park Slope, with smaller observant and culturally Jewish populations in Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Brighton Beach, and Coney Island.

Chinese American

[edit]

Over 200,000 Chinese Americans live throughout the southern parts of Brooklyn, primarily concentrated in Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, Gravesend, and Homecrest. Brooklyn is the borough that is home to the highest number of Chinatowns in New York City. The largest concentration is in Sunset Park along 8th Avenue, which has become known for its Chinese culture since the opening of the now-defunct Winley Supermarket in 1986 spurred widespread settlement in the area. It is called "Brooklyn's Chinatown" and originally it was a small Chinese enclave with Cantonese speakers being the main Chinese population during the late 1980s and 1990s, but since the 2000s, the Chinese population in the area dramatically shifted to majority Fuzhounese Americans, which contributed immensely to expanding this Chinatown, and bestowing the nicknames "Fuzhou Town (福州埠), Brooklyn" or the "Little Fuzhou (小福州)" of Brooklyn. Many Chinese restaurants can be found throughout Sunset Park, and the area hosts a popular Chinese New Year celebration. Since the 2000s going forward, the growing concentration of the Cantonese speaking population in Brooklyn have dramatically shifted to Bensonhurst/Gravesend and Homecrest creating newer Chinatowns of Brooklyn and these newer Brooklyn Chinatowns are known as "Brooklyn's Little Hong Kong/Guangdong" due to their Chinese populations being overwhelmingly Cantonese populated.[72][73]

Caribbean and African American

[edit]

Brooklyn's African American and Caribbean communities are spread throughout much of Brooklyn. Brooklyn's West Indian community is concentrated in the Crown Heights, Flatbush, East Flatbush, Kensington, and Canarsie neighborhoods in central Brooklyn. Brooklyn is home to the largest community of West Indians outside of the Caribbean. Although the largest West Indian groups in Brooklyn are Jamaicans, Guyanese and Haitians, there are West Indian immigrants from nearly every part of the Caribbean. Crown Heights and Flatbush are home to many of Brooklyn's West Indian restaurants and bakeries. Brooklyn has an annual, celebrated Carnival in the tradition of pre-Lenten celebrations in the islands.[74] Started by natives of Trinidad and Tobago, the West Indian Labor Day Parade takes place every Labor Day on Eastern Parkway. The Brooklyn Academy of Music also holds the DanceAfrica festival in late May, featuring street vendors and dance performances showcasing food and culture from all parts of Africa.[75][76] Since the opening of the IND Fulton Street Line in 1936, Bedford-Stuyvesant has been home to one of the most famous African American communities in the United States. Working-class communities remain prevalent in Brownsville, East New York and Coney Island, while remnants of similar communities in Prospect Heights, Fort Greene and Clinton Hill have endured amid widespread gentrification.

Hispanic American

[edit]In the aftermath of World War II and subsequent urban renewal initiatives that decimated longtime Manhattan enclaves (most notably on the Upper West Side), Puerto Rican migrants began to settle in such waterfront industrial neighborhoods as Sunset Park, Red Hook and Gowanus, near the shipyards and factories where they worked. The borough's Hispanic population diversified after the 1965 Hart-Cellar Act loosened restrictions on immigration from elsewhere in Latin America.

Bushwick has since emerged as the largest hub of Brooklyn's Hispanic American community. Like other Hispanic neighborhoods in New York City, Bushwick has an established Puerto Rican presence, along with an influx of many Dominicans, South Americans, Central Americans and Mexicans. As nearly 80% of Bushwick's population is Hispanic, its residents have created many businesses to support their various national and distinct traditions in food and other items. Sunset Park's population is 42% Hispanic, made up of these various ethnic groups. Brooklyn's main Hispanic groups are Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Dominicans and Ecuadorians; they are spread out throughout the borough. Puerto Ricans and Dominicans are predominant in Bushwick, Williamsburg's South Side and East New York. Mexicans (especially from the state of Puebla) now predominate alongside Chinese immigrants in Sunset Park, although remnants of the neighborhood's once-substantial postwar Puerto Rican and Dominican communities continue to reside below 39th Street. Save for Red Hook (which remained roughly one-fifth Hispanic American as of the 2010 Census), the South Side and Sunset Park, similar postwar communities in other waterfront neighborhoods—including western Park Slope, the north end of Greenpoint,[77] and Boerum Hill, long considered the northern subsection of Gowanus—largely disappeared by the turn of the century due to various factors, including deindustrialization, ensuing gentrification and suburbanization among more affluent Dominicans and Puerto Ricans. A Panamanian enclave exists in Crown Heights.

Russian and Ukrainian American

[edit]Brooklyn is also home to many Russians and Ukrainians, who are mainly concentrated in the areas of Brighton Beach and Sheepshead Bay. Brighton Beach features many Russian and Ukrainian businesses and has been nicknamed Little Russia and Little Odessa, respectively. In the 1970s, Soviet Jews won the right to immigrate, and many ended up in Brighton Beach. In recent years, the non-Jewish Russian and Ukrainian communities of Brighton Beach have grown, and the area is now home to a diverse collection of immigrants from across the former USSR. Smaller concentrations of Russian and Ukrainian Americans are scattered elsewhere in south Brooklyn, including Bay Ridge, Bensonhurst, Homecrest, Coney Island, and Mill Basin. A growing community of Uzbek Americans have settled alongside them in recent years due to their ability to speak Russian.[78][79]

Polish American

[edit]Brooklyn's Polish inhabitants are historically concentrated in Greenpoint, home to Little Poland. Other longstanding settlements in Borough Park and Sunset Park have endured, while more recent immigrants are scattered throughout the southern parts of Brooklyn alongside the Russian and Ukrainian American communities.

Italian American

[edit]Despite widespread migration to Staten Island and more suburban areas in metropolitan New York throughout the postwar era, notable concentrations of Italian Americans continue to reside in the neighborhoods of Bensonhurst, Dyker Heights, Bay Ridge, Bath Beach and Gravesend. Less perceptible remnants of older communities have persisted in Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens, where the homes of the remaining Italian Americans can often be contrasted with more recent upper middle class residents through the display of small Madonna statues, the retention of plastic-metal stoop awnings and the use of Formstone in house cladding. All of the aforementioned neighborhoods have retained Italian restaurants, bakeries, delicatessens, pizzerias, cafes and social clubs.

Arab American & Muslim

[edit]In the early 20th century, many Lebanese and Syrian Christians settled around Atlantic Avenue west of Flatbush Avenue in Boerum Hill; more recently, this area has evolved into a Yemeni commercial district. More recent, predominantly Muslim Arab immigrants, especially Egyptians and Lebanese, have moved into the southwest portion of Brooklyn, particularly to Bay Ridge, where many Middle Eastern restaurants, hookah lounges, halal grocers, Islamic shops and mosques line the commercial thoroughfares of Fifth and Third Avenues below 86th Street. Brighton Beach is home to a growing Pakistani American community, while Midwood is home to Little Pakistan along Coney Island Avenue (recently co-named Muhammad Ali Jinnah Way). Pakistani Independence Day is celebrated every year with parades and parties on Coney Island Avenue. Just to the north, Kensington is one of New York's several emerging Bangladeshi enclaves.

Irish American

[edit]Third-, fourth- and fifth-generation Irish Americans can be found throughout Brooklyn, with moderate concentrations[clarification needed] enduring in the neighborhoods of Windsor Terrace, Park Slope, Bay Ridge, Marine Park and Gerritsen Beach. Historical communities also existed in Vinegar Hill and other waterfront industrial neighborhoods, such as Greenpoint and Sunset Park. Paralleling the Italian American community, many moved to Staten Island and suburban areas in the postwar era. Those that stayed engendered close-knit, stable working-to-middle class communities through employment in the civil service (especially in law enforcement, transportation, and the New York City Fire Department) and the building and construction trades, while others were subsumed by the professional-managerial class and largely shed the Irish American community's distinct cultural traditions (including continued worship in the Catholic Church and other social activities, such as Irish stepdance and frequenting Irish American bars).[citation needed]

South Asian American

[edit]While not as extensive as the Indian American population in Queens, younger professionals of Asian Indian origin are finding Brooklyn to be a convenient alternative to Manhattan to find housing. Nearly 30,000 Indian Americans call Brooklyn home.[citation needed]

Brighton Beach is home to a growing Pakistani American community, while Midwood is home to Little Pakistan along Coney Island Avenue recently renamed Muhammad Ali Jinnah way. Pakistan Independence Day is celebrated every year with parades and parties on Coney Island Avenue. Just to the north, Kensington is one of New York's several emerging Bangladeshi enclaves.

Greek American

[edit]Brooklyn's Greek Americans live throughout the borough. A historical concentration has endured in Bay Ridge and adjacent areas, where there is a noticeable cluster of Hellenic-focused schools, businesses and cultural institutions. Other businesses are situated in Downtown Brooklyn near Atlantic Avenue. As in much of the New York metropolitan area, Greek-owned diners are found throughout the borough.

LGBTQ community

[edit]Brooklyn is home to a large and growing number of same-sex couples. Same-sex marriages in New York were legalized on June 24, 2011, and were authorized to take place beginning 30 days thereafter.[80] The Park Slope neighborhood spearheaded the popularity of Brooklyn among lesbians, and Prospect Heights has an LGBT residential presence.[81] Numerous neighborhoods have since become home to LGBT communities. Brooklyn Liberation March, the largest transgender-rights demonstration in LGBTQ history, took place on June 14, 2020, stretching from Grand Army Plaza to Fort Greene, focused on supporting Black transgender lives, drawing an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 participants.[82][83]

Artists-in-residence

[edit]Brooklyn became a preferred site for artists and hipsters to set up live/work spaces after being priced out of the same types of living arrangements in Manhattan. Various neighborhoods in Brooklyn, including Williamsburg, DUMBO, Red Hook, and Park Slope evolved as popular neighborhoods for artists-in-residence. However, rents and costs of living have since increased dramatically in these same neighborhoods, forcing artists to move to somewhat less expensive neighborhoods in Brooklyn or across Upper New York Bay to locales in New Jersey, such as Jersey City or Hoboken.[84]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1731 | 2,150 | — |

| 1756 | 2,707 | +25.9% |

| 1771 | 3,623 | +33.8% |

| 1786 | 3,966 | +9.5% |

| 1790 | 4,549 | +14.7% |

| 1800 | 5,740 | +26.2% |

| 1810 | 8,303 | +44.7% |

| 1820 | 11,187 | +34.7% |

| 1830 | 20,535 | +83.6% |

| 1840 | 47,613 | +131.9% |

| 1850 | 138,882 | +191.7% |

| 1860 | 279,122 | +101.0% |

| 1870 | 419,921 | +50.4% |

| 1880 | 599,495 | +42.8% |

| 1890 | 838,547 | +39.9% |

| 1900 | 1,166,582 | +39.1% |

| 1910 | 1,634,351 | +40.1% |

| 1920 | 2,018,356 | +23.5% |

| 1930 | 2,560,401 | +26.9% |

| 1940 | 2,698,285 | +5.4% |

| 1950 | 2,738,175 | +1.5% |

| 1960 | 2,627,319 | −4.0% |

| 1970 | 2,602,012 | −1.0% |

| 1980 | 2,230,936 | −14.3% |

| 1990 | 2,300,664 | +3.1% |

| 2000 | 2,465,326 | +7.2% |

| 2010 | 2,504,700 | +1.6% |

| 2020 | 2,736,074 | +9.2% |

| 2024 | 2,617,631 | −4.3% |

| 1731–1786[85] U.S. Decennial Census[86] 1790–1960[87] 1900–1990[88] 1990–2000[89] 2010[90] 2020[3] 2024[4] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[91] | ||

| Jurisdiction | Population | Land area | Density of population | GDP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borough | County | Census (2020) |

square miles |

square km |

people/ sq. mile |

people/ sq. km |

billions (2022 US$) 2 | |

Bronx

|

1,472,654 | 42.2 | 109.2 | 34,920 | 13,482 | 51.574 | ||

Kings

|

2,736,074 | 69.4 | 179.7 | 39,438 | 15,227 | 125.867 | ||

New York

|

1,694,251 | 22.7 | 58.7 | 74,781 | 28,872 | 885.652 | ||

Queens

|

2,405,464 | 108.7 | 281.6 | 22,125 | 8,542 | 122.288 | ||

Richmond

|

495,747 | 57.5 | 149.0 | 8,618 | 3,327 | 21.103 | ||

| 8,804,190 | 300.5 | 778.2 | 29,303 | 11,314 | 1,206.484 | |||

| 20,201,249 | 47,123.6 | 122,049.5 | 429 | 166 | 2,163.209 | |||

| Sources:[92][93][94][95] and see individual borough articles. | ||||||||

| Racial composition | 2020[96] | 2010[97] | 1990[57] | 1950[57] | 1900[57] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 37.6% | 42.8% | 46.9% | 92.2% | 98.3% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 35.4% | 35.7% | 40.1% | n/a | n/a |

| Black or African American | 26.7% | 34.3% | 37.9% | 7.6% | 1.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 18.9% | 19.8% | 20.1% | n/a | n/a |

| Asian | 13.6% | 10.5% | 4.8% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Two or more races | 8.7% | 3.0% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

At the 2020 census, 2,736,074 people lived in Brooklyn. The United States Census Bureau had estimated Brooklyn's population increased by 2.2% to 2,559,903 between 2010 and 2019. Brooklyn's estimated population represented 30.7% of New York City's estimated population of 8,336,817; 33.5% of Long Island's population of 7,701,172; and 13.2% of New York State's population of 19,542,209.[98] In 2020, the government of New York City projected Brooklyn's population at 2,648,403.[99] The 2019 census estimates determined there were 958,567 households with an average of 2.66 persons per household.[100] There were 1,065,399 housing units in 2019 and a median gross rent of $1,426. Citing growth, Brooklyn gained 9,696 building permits at the 2019 census estimates program.

Ethnic groups

[edit]The 2020 American Community Survey estimated the racial and ethnic makeup of Brooklyn was 35.4% non-Hispanic white, 26.7% Black or African American, 0.9% American Indian or Alaska Native, 13.6% Asian, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 4.1% two or more races, and 18.9% Hispanic or Latin American of any race.[96] According to the 2010 United States census, Brooklyn's population was 42.8% White, including 35.7% non-Hispanic White; 34.3% Black, including 31.9% non-Hispanic black; 10.5% Asian; 0.5% Native American; 0.0% (rounded) Pacific Islander; 3.0% Multiracial American; and 8.8% from other races. Hispanics and Latinos made up 19.8% of Brooklyn's population.[104] In 2010, Brooklyn had some neighborhoods segregated based on race, ethnicity, and religion. Overall, the southwest half of Brooklyn is racially mixed although it contains few black residents; the northeast section is mostly black and Hispanic/Latino.[105]

Languages

[edit]Brooklyn has a high degree of linguistic diversity. As of 2010, 54.1% (1,240,416) of Brooklyn residents ages 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 17.2% (393,340) spoke Spanish, 6.5% (148,012) Chinese, 5.3% (121,607) Russian, 3.5% (79,469) Yiddish, 2.8% (63,019) French Creole, 1.4% (31,004) Italian, 1.2% (27,440) Hebrew, 1.0% (23,207) Polish, 1.0% (22,763) French, 1.0% (21,773) Arabic, 0.9% (19,388) various Indic languages, 0.7% (15,936) Urdu, and African languages were spoken as a main language by 0.5% (12,305) of the population over the age of five. In total, 45.9% (1,051,456) of Brooklyn's population ages 5 and older spoke a mother tongue other than English.[106]

Culture

[edit]

Brooklyn has played a major role in various aspects of American culture, including literature, cinema, and theater. Brooklyn's accent has often been portrayed as the "typical New Yorker accent" in American media, although this accent and its stereotypes are supposedly diminishing in currency.[107] Brooklyn's official colors are blue and gold.[108]

Cultural venues

[edit]Brooklyn hosts the world-renowned Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Philharmonic, and the second-largest public art collection in the United States, housed in the Brooklyn Museum.

The Brooklyn Museum, opened in 1897, is New York City's second-largest public art museum. It has in its permanent collection more than 1.5 million objects, from ancient Egyptian masterpieces to contemporary art. The Brooklyn Children's Museum, the world's first museum dedicated to children, opened in December 1899. The only such New York State institution accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, it is one of the few globally to have a permanent collection – over 30,000 cultural objects and natural history specimens.

The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) includes a 2,109-seat opera house, an 874-seat theater, and the art-house BAM Rose Cinemas. Bargemusic and St. Ann's Warehouse are on the other side of Downtown Brooklyn in the DUMBO arts district. Brooklyn Technical High School has the second-largest auditorium in New York City (after Radio City Music Hall), with a seating capacity of over 3,000.[109]

Media

[edit]Local periodicals

[edit]Brooklyn has several local newspapers: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Bay Currents (Oceanfront Brooklyn), Brooklyn View, The Brooklyn Paper, and Courier-Life Publications. Courier-Life Publications, owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, is Brooklyn's largest chain of newspapers. Brooklyn is also served by the major New York dailies, including The New York Times, the New York Daily News, and the New York Post. Several others are now defunct, including the Brooklyn Union (1867–1937),[110][111] and the Brooklyn Times.[110]

The borough is home to the arts and politics monthly Brooklyn Rail, as well as the arts and cultural quarterly Cabinet. Hello Mr. is also published in Brooklyn.

Brooklyn Magazine is one of the few glossy magazines about Brooklyn. Several others are now defunct, including BKLYN Magazine (a bimonthly lifestyle book owned by Joseph McCarthy, that saw itself as a vehicle for high-end advertisers in Manhattan and was mailed to 80,000 high-income households), Brooklyn Bridge Magazine, The Brooklynite (a free, glossy quarterly edited by Daniel Treiman), and NRG (edited by Gail Johnson and originally marketed as a local periodical for Clinton Hill and Fort Greene, but expanded in scope to become the self-proclaimed "Pulse of Brooklyn" and then the "Pulse of New York").[112]

Ethnic press

[edit]Brooklyn has a thriving ethnic press. El Diario La Prensa, the largest and oldest Spanish-language daily newspaper in the United States, maintains its corporate headquarters at 1 MetroTech Center in Downtown Brooklyn.[113] Major ethnic publications include the Brooklyn–Queens Catholic paper The Tablet, Hamodia, an Orthodox Jewish daily, and The Jewish Press, an Orthodox Jewish weekly. Many nationally distributed ethnic newspapers are based in Brooklyn. Over 60 ethnic groups, writing in 42 languages, publish some 300 non-English language magazines and newspapers in New York City. Among them is the quarterly L'Idea, a bilingual magazine printed in Italian and English since 1974. In addition, many newspapers published abroad, such as The Daily Gleaner and The Star of Jamaica, are available in Brooklyn.[citation needed] Our Time Press, published weekly by DBG Media, covers the Village of Brooklyn with a motto of "The Local Paper with the Global View".

Television

[edit]The City of New York has an official television station, run by NYC Media, which features programming based in Brooklyn. Brooklyn Community Access Television is the borough's public access channel.[114] Its studios are at the BRIC Arts Media venue, called BRIC House, located on Fulton Street in the Fort Greene section of the borough.[115]

Events

[edit]- The annual Coney Island Mermaid Parade (mid-to-late June) is a costume-and-float parade.[116]

- Coney Island also hosts the annual Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest (July 4).[116]

- The annual Labor Day Carnival (also known as the Labor Day Parade or West Indian Day Parade) takes place along Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights.

- The Art of Brooklyn Film Festival runs annually around the second week of June.[117]

Economy

[edit]

Brooklyn's job market is driven by three main factors: the performance of the national and city economy, population flows and the borough's position as a convenient back office for New York's businesses.[118]

Forty-four percent of Brooklyn's employed population, or 410,000 people, work in the borough; more than half of the borough's residents work outside its boundaries. As a result, economic conditions in Manhattan are important to the borough's jobseekers. Strong international immigration to Brooklyn generates jobs in services, retailing and construction.[118]

Since the late 20th century, Brooklyn has benefited from a steady influx of financial back office operations from Manhattan, the rapid growth of a high-tech and entertainment economy in DUMBO, and strong growth in support services such as accounting, personal supply agencies, and computer services firms.[118]

Jobs in the borough were traditionally concentrated in manufacturing, but since 1975, Brooklyn has shifted from a manufacturing-based to a service-based economy. In 2004, 215,000 Brooklyn residents worked in the services sector, while 27,500 worked in manufacturing. Although manufacturing has declined, a substantial base has remained in apparel and niche manufacturing concerns such as furniture, fabricated metals, and food products.[119] The pharmaceutical company Pfizer was founded in Brooklyn in 1869 and had a manufacturing plant in the borough for many years that employed thousands of workers, but the plant shut down in 2008. However, new light-manufacturing concerns in packaging organic and high-end food have sprung up in the old plant.[120]

Established as a shipbuilding facility in 1801, the Brooklyn Navy Yard employed 70,000 people at its peak during World War II and was then the largest employer in the borough. The Missouri, the ship on which the Japanese formally surrendered, was built there, as was the Maine, whose sinking off Havana led to the start of the Spanish–American War. The iron-sided Civil War vessel the Monitor was built in Greenpoint. From 1968 to 1979 Seatrain Shipbuilding was the major employer.[121] Later tenants include industrial design firms, food processing businesses, artisans, and the film and television production industry. About 230 private-sector firms providing 4,000 jobs are at the Yard.

Construction and services are the fastest-growing sectors.[122] Most employers in Brooklyn are small businesses. In 2000, 91% of the approximately 38,704 business establishments in Brooklyn had fewer than 20 employees.[123] As of August 2008[update], the borough's unemployment rate was 5.9%.[124]

Brooklyn is also home to many banks and credit unions. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, there were 37 banks and 26 credit unions operating in the borough in 2010.[125][126]

The rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn has generated over US$10 billion of private investment and $300 million in public improvements since 2004. Brooklyn is also attracting numerous high technology start-up companies, as Silicon Alley, the metonym for New York City's entrepreneurship ecosystem, has expanded from Lower Manhattan into Brooklyn.[127]

Parks and other attractions

[edit]

- Brooklyn Botanic Garden: adjacent to Prospect Park is the 52-acre (21 ha) botanical garden, which includes a cherry tree esplanade, a one-acre (0.4 ha) rose garden, a Japanese hill, and pond garden, a fragrance garden, a water lily pond esplanade, several conservatories, a rock garden, a native flora garden, a bonsai tree collection, and children's gardens and discovery exhibits.

- Coney Island developed as a playground for the rich in the early 1900s, but it grew as one of America's first amusement grounds and attracted crowds from all over New York. The Cyclone rollercoaster, built-in 1927, is on the National Register of Historic Places. The 1920 Wonder Wheel and other rides are still operational. Coney Island went into decline in the 1970s but has undergone a renaissance.[128]

- Floyd Bennett Field: the first municipal airport in New York City and long-closed for operations, is now part of the National Park System. Many of the historic hangars and runways are still extant. Nature trails and diverse habitats are found within the park, including salt marsh and a restored area of shortgrass prairie that was once widespread on the Hempstead Plains.

- Green-Wood Cemetery, founded by the social reformer Henry Evelyn Pierrepont in 1838,[129] is an early rural cemetery. It is the burial ground of many notable New Yorkers.

- Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge: a unique Federal wildlife refuge straddling the Brooklyn–Queens border, part of Gateway National Recreation Area

- New York Transit Museum displays historical artifacts of Greater New York's subway, commuter rail, and bus systems; it is at Court Street, a former Independent Subway System station in Brooklyn Heights on the Fulton Street Line.

- Prospect Park is a public park in central Brooklyn encompassing 585 acres (2.37 km2).[130] The park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who created Manhattan's Central Park. Attractions include the Long Meadow, a 90-acre (36 ha) meadow, the Picnic House, which houses offices and a hall that can accommodate parties with up to 175 guests; Litchfield Villa, Prospect Park Zoo, the Boathouse, housing a visitors center and the first urban Audubon Center;[131] Brooklyn's only lake, covering 60 acres (24 ha); the Prospect Park Bandshell that hosts free outdoor concerts in the summertime; and various sports and fitness activities including seven baseball fields. Prospect Park hosts a popular annual Halloween Parade.

- Fort Greene Park is a public park in the Fort Greene Neighborhood. The park contains the Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument, a monument to American prisoners during the Revolutionary War.

Sports

[edit]

Brooklyn's major professional sports team is the NBA's Brooklyn Nets. The Nets moved into the borough in 2012, and play their home games at Barclays Center in Prospect Heights. Previously, the Nets had played in Uniondale, New York and in New Jersey.[132] In April 2020, the New York Liberty of the WNBA were sold to the Nets' owners and moved their home venue from Madison Square Garden to the Barclays Center.

Barclays Center was also the home arena for the NHL's New York Islanders full-time from 2015 to 2018, then part-time from 2018 to 2020 (alternating with Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale). The Islanders had originally played at Nassau Coliseum full-time since their inception until 2015 when their lease at the venue expired and the team moved to Barclays Center. In 2020, the team returned to Nassau Coliseum full-time for one season before moving to the UBS Arena in Elmont, New York in 2021.

Brooklyn also has a storied sports history. It has been home to many famous sports figures such as Joe Paterno, Vince Lombardi, Mike Tyson, Zab Judah, Joe Torre, Sandy Koufax, Billy Cunningham and Vitas Gerulaitis. Basketball legend Michael Jordan was born in Brooklyn though he grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina.

In the earliest days of organized baseball, Brooklyn teams dominated the new game. The second recorded game of baseball was played near what is now Fort Greene Park on October 24, 1845. Brooklyn's Excelsiors, Atlantics and Eckfords were the leading teams from the mid-1850s through the Civil War, and there were dozens of local teams with neighborhood league play, such as at Mapleton Oval.[133] During this "Brooklyn era", baseball evolved into the modern game: the first fastball, first changeup, first batting average, first triple play, first pro baseball player, first enclosed ballpark, first scorecard, first known African-American team, first black championship game, first road trip, first gambling scandal, and first eight pennant winners were all in or from Brooklyn.[134]

Brooklyn's most famous historical team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, named for "trolley dodgers" played at Ebbets Field.[135] In 1947 Jackie Robinson was hired by the Dodgers as the first African-American player in Major League Baseball in the modern era. In 1955, the Dodgers, perennial National League pennant winners, won the only World Series for Brooklyn against their rival New York Yankees. The event was marked by mass euphoria and celebrations. Just two years later, the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles. Walter O'Malley, the team's owner at the time, is still vilified, even by Brooklynites too young to remember the Dodgers as Brooklyn's ball club.

After a 43-year hiatus, professional baseball returned to the borough in 2001 with the Brooklyn Cyclones, a minor league team that plays in MCU Park in Coney Island. They are an affiliate of the New York Mets.

The minor-league New York Cosmos soccer club played its home games at MCU Park in 2017.[136] A new Brooklyn FC will begin play in 2024, fielding a women's team in the first-division USL Super League and a men's team in the second-division USL Championship beginning in 2025.[137][138]

Brooklyn once had a National Football League team named the Brooklyn Lions in 1926, who played at Ebbets Field.[139]

In rugby union, Rugby United New York joined Major League Rugby in 2019 and played their home games at MCU Park through the 2021 season.

Brooklyn has one of the most active recreational fishing fleets in the United States. In addition to a large private fleet along Jamaica Bay, there is a substantial public fleet within Sheepshead Bay. Species caught include Black Fish, Porgy, Striped Bass, Black Sea Bass, Fluke, and Flounder.[140][141][142]

Government and politics

[edit]

Each of New York City's five counties, coterminous with each borough, has its own criminal court system and District Attorney, the chief public prosecutor who is directly elected by popular vote. Brooklyn has 16 City Council members, the largest number of any of the five boroughs. The Brooklyn Borough Government includes a borough government president and a court, library, borough government board, head of borough government, deputy head of borough government and deputy borough government president.

Brooklyn has 18 of the city's 59 community districts, each served by an unpaid community board with advisory powers under the city's Uniform Land Use Review Procedure. Each board has a paid district manager who acts as an interlocutor with city agencies. The Kings County Democratic County Committee (aka the Brooklyn Democratic Party) is the county committee of the Democratic Party in Brooklyn.

The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Main Post Office is located at 271 Cadman Plaza East in Downtown Brooklyn.[143]

| Year | Republican / Whig | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 233,964 | 27.40% | 601,265 | 70.43% | 18,515 | 2.17% |

| 2020 | 202,772 | 22.14% | 703,310 | 76.78% | 9,927 | 1.08% |

| 2016 | 141,044 | 17.51% | 640,553 | 79.51% | 24,008 | 2.98% |

| 2012 | 124,551 | 16.90% | 604,443 | 82.02% | 7,988 | 1.08% |

| 2008 | 151,872 | 19.99% | 603,525 | 79.43% | 4,451 | 0.59% |

| 2004 | 167,149 | 24.30% | 514,973 | 74.86% | 5,762 | 0.84% |

| 2000 | 96,609 | 15.65% | 497,513 | 80.60% | 23,115 | 3.74% |

| 1996 | 81,406 | 15.08% | 432,232 | 80.07% | 26,195 | 4.85% |

| 1992 | 133,344 | 22.93% | 411,183 | 70.70% | 37,067 | 6.37% |

| 1988 | 178,961 | 32.60% | 363,916 | 66.28% | 6,142 | 1.12% |

| 1984 | 230,064 | 38.29% | 368,518 | 61.34% | 2,189 | 0.36% |

| 1980 | 200,306 | 38.44% | 288,893 | 55.44% | 31,893 | 6.12% |

| 1976 | 190,728 | 31.08% | 419,382 | 68.34% | 3,533 | 0.58% |

| 1972 | 373,903 | 48.96% | 387,768 | 50.78% | 1,949 | 0.26% |

| 1968 | 247,936 | 31.99% | 489,174 | 63.12% | 37,859 | 4.89% |

| 1964 | 229,291 | 25.05% | 684,839 | 74.80% | 1,373 | 0.15% |

| 1960 | 327,497 | 33.51% | 646,582 | 66.16% | 3,227 | 0.33% |

| 1956 | 460,456 | 45.23% | 557,655 | 54.77% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 446,708 | 39.82% | 656,229 | 58.50% | 18,765 | 1.67% |

| 1948 | 330,494 | 30.49% | 579,922 | 53.51% | 173,401 | 16.00% |

| 1944 | 393,926 | 34.01% | 758,270 | 65.46% | 6,168 | 0.53% |

| 1940 | 394,534 | 34.44% | 742,668 | 64.83% | 8,365 | 0.73% |

| 1936 | 212,852 | 21.85% | 738,306 | 75.78% | 23,143 | 2.38% |

| 1932 | 192,536 | 25.04% | 514,172 | 66.86% | 62,300 | 8.10% |

| 1928 | 245,622 | 36.13% | 404,393 | 59.48% | 29,822 | 4.39% |

| 1924 | 236,877 | 47.50% | 158,907 | 31.87% | 102,903 | 20.63% |

| 1920 | 292,692 | 63.32% | 119,612 | 25.88% | 49,944 | 10.80% |

| 1916 | 120,752 | 46.90% | 125,625 | 48.79% | 11,080 | 4.30% |

| 1912 | 51,239 | 20.94% | 109,748 | 44.86% | 83,676 | 34.20% |

| 1908 | 119,789 | 50.64% | 96,756 | 40.90% | 20,025 | 8.46% |

| 1904 | 113,246 | 48.12% | 111,855 | 47.53% | 10,216 | 4.34% |

| 1900 | 108,977 | 49.57% | 106,232 | 48.32% | 4,639 | 2.11% |

| 1896 | 109,135 | 56.35% | 76,882 | 39.70% | 7,659 | 3.95% |

| 1892 | 70,505 | 39.97% | 100,160 | 56.78% | 5,720 | 3.24% |

| 1888 | 70,052 | 45.49% | 82,507 | 53.58% | 1,430 | 0.93% |

| 1884 | 53,516 | 42.37% | 69,264 | 54.83% | 3,541 | 2.80% |

| 1880 | 51,751 | 45.66% | 61,062 | 53.88% | 516 | 0.46% |

| 1876 | 39,066 | 40.41% | 57,556 | 59.53% | 62 | 0.06% |

| 1872 | 33,369 | 46.68% | 38,108 | 53.31% | 10 | 0.01% |

| 1868 | 27,707 | 41.02% | 39,838 | 58.98% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1864 | 20,838 | 44.75% | 25,726 | 55.25% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1860 | 15,883 | 43.56% | 20,583 | 56.44% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1856 | 7,846 | 25.58% | 14,174 | 46.22% | 8,647 | 28.20% |

| 1852 | 8,496 | 43.97% | 10,628 | 55.00% | 199 | 1.03% |

| 1848 | 7,511 | 56.59% | 4,882 | 36.78% | 879 | 6.62% |

| 1844 | 5,107 | 51.94% | 4,648 | 47.27% | 77 | 0.78% |

| 1840 | 3,293 | 50.86% | 3,157 | 48.76% | 24 | 0.37% |

| 1836 | 1,868 | 44.59% | 2,321 | 55.41% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1832 | 1,264 | 42.06% | 1,741 | 57.94% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1828 | 1,053 | 43.84% | 1,349 | 56.16% | 0 | 0.00% |

As is the case with sister boroughs Manhattan and the Bronx, Brooklyn has not voted for a Republican in a national presidential election since Calvin Coolidge in 1924. In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 79.4% of the vote in Brooklyn while Republican John McCain received 20.0%. In 2012, Barack Obama increased his Democratic margin of victory in the borough, dominating Brooklyn with 82.0% of the vote to Republican Mitt Romney's 16.9%.[144]

In 2024, Republican Donald Trump reached 27% of the vote, and held Kamala Harris at just over 70%, a significant shift from Joe Biden's performance of over 76% in 2020. While still a decisive Democratic victory, this was the strongest Republican support in Brooklyn since 1988, and the largest number of raw Republican votes there since 1972.[144]

Federal representation

[edit]As of 2023, four Democrats and one Republican represented Brooklyn in the United States House of Representatives. One congressional district lies entirely within the borough.[147]

- Nydia Velázquez (first elected in 1992) represents New York's 7th congressional district, which includes the central-west Brooklyn neighborhoods of Boerum Hill, Brooklyn Heights, Bushwick, Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, Dumbo, East New York, East Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Gowanus, Red Hook, Sunset Park, and Williamsburg. The district also covers a small portion of Queens.[147]

- Hakeem Jeffries (first elected in 2012) represents New York's 8th congressional district, which includes the southern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Bergen Beach, Brighton Beach, Brownsville, Canarsie, Clinton Hill, Coney Island, East Flatbush, East New York, Fort Greene, Gerritsen Beach, Marine Park, Mill Basin, Ocean Hill, Sheepshead Bay, and Spring Creek. The district also covers a small portion of Queens.[147]

- Yvette Clarke (first elected in 2006) represents New York's 9th congressional district, which includes the central and southern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Crown Heights, East Flatbush, Flatbush, Midwood, Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, and Windsor Terrace.[147]

- Dan Goldman (first elected in 2022) represents New York's 10th congressional district, which includes the southwestern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Midwood, Red Hook, Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, Borough Park, Gravesend, Kensington, and Mapleton. The district also covers the West Side of Manhattan.[147]

- Nicole Malliotakis (first elected in 2020) represents New York's 11th congressional district, which includes the southwestern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bensonhurst, Gravesend, Bath Beach, Bay Ridge, and Dyker Heights. The district also covers all of Staten Island.[147]

| Party | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | 69.7 | 69.2 | 70.0 | 70.1 | 70.6 | 70.3 | 70.7 | 70.8 | 70.8 | 71.0 |

| Republican | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 11.5 |

| Other | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| No affiliation | 16.5 | 16.9 | 16.1 | 16.2 | 16.3 | 16.5 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 15.4 | 15.2 |

Housing

[edit]Brooklyn offers a wide array of private housing, as well as public housing, which is administered by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). Affordable rental and co-operative housing units throughout the borough were created under the Mitchell–Lama Housing Program.[148]

There were 1,101,441 housing units in 2022[90] at an average density of 15,876 units per square mile (6,130/km2). Public housing administered by NYCHA accounts for more than 100,000 residents in nearly 50,000 units in 2023.[149]

Education

[edit]

Education in Brooklyn is provided by a vast number of public and private institutions. Non-charter public schools in the borough are managed by the New York City Department of Education,[150] the largest public school system in the United States.

Brooklyn Technical High School, commonly called Brooklyn Tech, a New York City public high school, is the largest specialized high school for science, mathematics, and technology in the United States.[151] Brooklyn Tech opened in 1922. Brooklyn Tech is across the street from Fort Greene Park. This high school was built from 1930 to 1933 at a cost of about $6 million and is 12 stories high. It covers about half of a city block.[152] Brooklyn Tech is noted for its famous alumni[153] (including two Nobel Laureates), its academics, and a large number of graduates attending prestigious universities.

Higher education

[edit]Public colleges

[edit]Brooklyn College is a senior college of the City University of New York (CUNY), and was the first public coeducational liberal arts college in New York City. The college ranked in the top 10 nationally for the second consecutive year in Princeton Review's 2006 guidebook, America's Best Value Colleges. Many of its students are first and second-generation Americans. Founded in 1970, Medgar Evers College is a senior college of the City University of New York. The college offers programs at the baccalaureate and associate degree levels, as well as adult and continuing education classes for central Brooklyn residents, corporations, government agencies, and community organizations. Medgar Evers College is a few blocks east of Prospect Park in Crown Heights.

CUNY's New York City College of Technology (City Tech) of The City University of New York (Downtown Brooklyn/Brooklyn Heights) is the largest public college of technology in New York State and a national model for technological education. Established in 1946, City Tech can trace its roots to 1881 when the Technical Schools of the Metropolitan Museum of Art were renamed the New York Trade School. That institution—which became the Voorhees Technical Institute many decades later—was soon a model for the development of technical and vocational schools worldwide. In 1971, Voorhees was incorporated into City Tech.

SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, founded as the Long Island College Hospital in 1860, is the oldest hospital-based medical school in the United States. The Medical Center comprises the College of Medicine, College of Health Related Professions, College of Nursing, School of Public Health, School of Graduate Studies, and University Hospital of Brooklyn. The Nobel Prize winner Robert F. Furchgott was a member of its faculty. Half of the Medical Center's students are minorities or immigrants. The College of Medicine has the highest percentage of minority students of any medical school in New York State.

Private colleges

[edit]Adelphi University, based in Garden City, moved its Manhattan Campus in 2023 to a new location on Livingston Street in Downtown Brooklyn. The move marks a return to Brooklyn for the university, which originated on Adelphi Street with the Adelphi Academy. The facility is shared with St. Francis College, which has created a new campus at 179 Livingston Street.[154]

Brooklyn Law School was founded in 1901 and is notable for its diverse student body. Women and African Americans were enrolled in 1909. According to the Leiter Report, a compendium of law school rankings published by Brian Leiter, Brooklyn Law School places 31st nationally for the quality of students.[155]

Long Island University is a private university headquartered in Brookville on Long Island, with a campus in Downtown Brooklyn with 6,417 undergraduate students. The Brooklyn campus has strong science and medical technology programs, at the graduate and undergraduate levels.

Pratt Institute, in Clinton Hill, is a private college founded in 1887 with programs in engineering, architecture, and the arts. Some buildings in the school's Brooklyn campus are official landmarks. Pratt has over 4700 students, with most at its Brooklyn campus. Graduate programs include a library and information science, architecture, and urban planning. Undergraduate programs include architecture, construction management, writing, critical and visual studies, industrial design and fine arts, totaling over 25 programs in all.