Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hypergraphia

View on Wikipedia

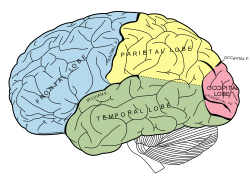

Hypergraphia is a behavioral condition characterized by the intense desire to write or draw. Forms of hypergraphia can vary in writing style and content. It is a symptom associated with temporal lobe changes in epilepsy and in Geschwind syndrome.[1] Structures that may have an effect on hypergraphia when damaged due to temporal lobe epilepsy are the hippocampus and Wernicke's area. Aside from temporal lobe epilepsy, chemical causes may be responsible for inducing hypergraphia.

Characteristics

[edit]Writing style

[edit]American neurologists Stephen Waxman and Norman Geschwind were the first to describe hypergraphia, in the 1970s.[2] The patients they observed displayed highly compulsive detailed writing, sometimes with literary creativity. The patients kept diaries, which some used to meticulously document minute details of their everyday activities, write poetry, or create lists. Case 1 of their study wrote lists of her relatives, her likes and dislikes, and the furniture in her apartment. Beside lists, the patient wrote poetry, often with a moral or philosophical undertone. She described an incident in which she wrote the lyrics of a song she learned when she was 17 several hundred times and another incident in which she felt the urge to write a word over and over again. Another patient wrote aphorisms and certain sentences in repetition.[2]

A patient from a separate study experienced continuous "rhyming in his head" for five years after a seizure and said that he "felt the need to write them down."[3] The patient did not talk in rhyme, nor did he read poetry. Language capacity and mental status were normal for this patient, except for recorded right-temporal spikes on electroencephalograms. This patient had right-hemisphere epilepsy. Functional MRI scans of other studies suggest that rhyming behavior is produced in the left hemisphere, but Mendez proposed that postictal hypoactivity of the right hemisphere may induce a release of writing and rhyming abilities in the left hemisphere.[3]

Content

[edit]

In addition to writing in different forms (poetry, books, repetition of one word), hypergraphia patients differ in the complexity of their writings. While some writers (e.g. Alice Flaherty[4] and Dyane Harwood[5]) use their hypergraphia to help them write extensive papers and books, most patients do not write things of substance. Flaherty describes hypergraphia as a result of decreased temporal lobe function which disinhibits frontal lobe idea and language generation, "sometimes at the expense of quality."[6] Patients hospitalized with temporal lobe epilepsy and other disorders causing hypergraphia have written memos and lists (like their favorite songs) and recorded their dreams in extreme length and detail.[6]

There are many accounts of patients writing in nonsensical patterns including writing in a center-seeking spiral starting around the edges of a piece of paper.[7] In one case study, a patient even wrote backward, so that the writing could only be interpreted with the aid of a mirror.[2] Sometimes the writing can consist of scribbles and frantic, random thoughts that are quickly jotted down on paper very frequently. Grammar can be present, but the meaning of these thoughts is generally hard to grasp and the sentences are loose.[7] In some cases, patients write extremely detailed accounts of events that are occurring or descriptions of where they are.[7]

In some cases, hypergraphia can manifest with compulsive drawing.[8] The composer Robert Schumann, during periods of high musical output, also wrote many long letters to his wife Clara; similarly, Vincent van Gogh had much more written correspondence during bouts of intense painting.[4] Many drawings by patients with hypergraphia exhibit repetition and a high level of detail, sometimes mixing both compulsive writing and drawing together.[9]

Causes

[edit]Some studies have suggested that hypergraphia is related to bipolar disorder, hypomania, and schizophrenia.[10] Although creative ability was observed in the patients of these studies, signs of creativity were observed, not hypergraphia specifically. Therefore, it is difficult to say with absolute certainty that hypergraphia is a symptom of these psychiatric illnesses because creativity in patients with bipolar disorder, hypomania, or schizophrenia may manifest into something aside from writing. However, other studies have shown significant accounts between hypergraphia and temporal lobe epilepsy[11] and chemical causes.[12]

Temporal lobe epilepsy

[edit]

Hypergraphia was first studied as a symptom of temporal lobe epilepsy, a condition of reoccurring seizures caused by excessive neuronal activity, but it is not a common symptom among patients. Less than 10 percent of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy exhibit characteristics of hypergraphia.[medical citation needed] Temporal lobe epilepsy patients may exhibit irritability, discomfort, or an increasing feeling of dread if their writing activity is disrupted.[13] To elicit such responses when interrupting their writing suggests that hypergraphia is a compulsive condition, resulting in an obsessive motivation to write.[10] A temporal lobe epilepsy may influence frontotemporal connections in such a way that the drive to write is increased in the frontal lobe, beginning with the prefrontal and premotor cortex planning out what to write, and then leading to the motor cortex (located next to the central fissure) executing the physical movement of writing.[10]

Most temporal lobe epilepsy patients who suffer from hypergraphia can write words, but not all may have the capacity to write complete sentences that have meaning.[7]

Bipolar disorder

[edit]The disorder most often associated with high-output writers is bipolar disorder, especially during hypomania.[14] In fact, temporal lobe epilepsy is more likely to produce hypergraphia if it also produces manic symptoms. While depression has been linked to increased writing, it appears that most writers with depression write little while depressed, and high output periods correspond to rebound mood elevation after the end of a depression, or in mixed mood states.[14]

Chemicals

[edit]Drugs that boost mood and energy have been known to induce hypergraphia, possibly by increasing activity in brain networks utilizing one of the body's neurotransmitters, dopamine. Dopamine has been known to decrease latent inhibition, which causes a decrease in the ability to habituate to screen out unexpected stimuli. Low latent inhibition leads to an excessive level of stimulation and could contribute to the onset of hypergraphia and general creativity.[15] This research implies that there is a direct correlation between the levels of dopamine between neuronal synapses and the level of creativity exhibited by the patient. Dopamine agonists increase the levels of dopamine between synapses which results in higher levels of creativity, and the opposite is true for dopamine antagonists.

In one case study, a patient taking donepezil reported an elevation in mood and energy levels which led to hypergraphia and other excessive forms of speech (such as singing).[16] Six other cases of patients taking donepezil and experiencing mania have been previously reported. These patients also had cases of dementia, cognitive impairment from a cerebral aneurysm, bipolar I disorder, and/or depression. Researchers are unsure why donepezil can induce mania and hypergraphia. It could potentially result from an increase in acetylcholine levels, which would have an effect on the other neurotransmitters in the brain.[16]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Several regions of the brain are involved in the act of written composition. Handwriting depends on the superior parietal cortex, and motor control areas in the frontal lobe and cerebellum.[17] An area of the frontal lobe that is especially active is Exner's area, located in the premotor cortex.[17] Writing creatively and generating ideas, on the other hand, activates multiple sites in the limbic system and cerebral cortex, including the left inferior frontal gyrus (BA 45) and the left temporal pole (BA 38).[18] Lesions to Wernicke's area (in the left temporal lobe) can increase speech output, which can sometimes manifest itself in writing.[6] In one study, patients with hippocampal atrophy showed signs of having Geschwind syndrome, including hypergraphia.[19] While epilepsy-induced hypergraphia is usually lateralized to the left cerebral hemisphere in the language areas, hypergraphia associated with lesions and other brain damage usually occurs in the right cerebral hemisphere.[20] Lesions to the right side of the brain usually cause hypergraphia because they can disinhibit language function on the left side of the brain.[6] Hypergraphia has also been known to be caused by right hemisphere strokes and tumors.[7][21]

Society and culture

[edit]Hypergraphia was one of the central issues in the 1999 trial of Alvin Ridley for the imprisonment and murder of his wife Virginia Ridley.[22] The mysterious woman, who had died in bed of apparent suffocation, had remained secluded in her home for 27 years in the small town of Ringgold, Georgia, United States. Her 10,000-page journal, which provided abundant evidence that she suffered from epilepsy and had remained housebound of her own will, was instrumental in the acquittal of her husband.[22]

In 1969, Isaac Asimov said "I am a compulsive writer".[23] Other artistic figures reported to have been affected by hypergraphia include Vincent van Gogh,[citation needed] Fyodor Dostoevsky,[24] and Robert Burns.[25] Alice in Wonderland author Lewis Carroll is also said to have had the condition,[26] having written more than 98,000 letters in various formats throughout his life. Some were written backward, in rebus, and in patterns, as with "The Mouse's Tale" in Alice.

Eleanor Alice Burford, whose pen-names included Jean Plaidy, Victoria Holt, Philippa Carr, Eleanor Burford, Elbur Ford, Kathleen Kellow, Anna Percival, and Ellalice Tate, described herself as a compulsive writer.

Naomi Mitchison, often called a doyenne of Scottish literature, writing over 90 books of historical and science fiction, travel writing and autobiography, has been described as a compulsive writer.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Devinsky J, Schachter S (August 2009). "Norman Geschwind's contribution to the understanding of behavioral changes in temporal lobe epilepsy: the February 1974 lecture". Epilepsy Behav (Biography, History article). 15 (4): 417–24. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.06.006. PMID 19640791. S2CID 22179745.

- ^ a b c Waxman, SG; Geschwind, N (March 2005). "Hypergraphia in temporal lobe epilepsy. 1974". Epilepsy & Behavior. 6 (2): 282–91. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.11.022. PMID 15710320. S2CID 32956175.

- ^ a b Mendez, MF (Fall 2005). "Hypergraphia for poetry in an epileptic patient". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 17 (4): 560–1. doi:10.1176/jnp.17.4.560. PMID 16388002.

- ^ a b Flaherty, Alice W. (April 28, 2015). The Midnight Disease: The Drive to Write, Writer's Block, and the Creative Brain. Mariner Books.

- ^ Harwood, Dyane; Henshaw, Dr Carol (October 10, 2017). Birth of a New Brain: Healing from Postpartum Bipolar Disorder. Post Hill Press.

- ^ a b c d Flaherty AW (December 2005). "Frontotemporal and dopaminergic control of idea generation and creative drive". J. Comp. Neurol. (Review). 493 (1): 147–53. doi:10.1002/cne.20768. PMC 2571074. PMID 16254989.

- ^ a b c d e Yamadori A, Mori E, Tabuchi M, Kudo Y, Mitani Y (October 1986). "Hypergraphia: a right hemisphere syndrome". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 49 (10): 1160–4. doi:10.1136/jnnp.49.10.1160. PMC 1029050. PMID 3783177.

- ^ Roberts, JK; Robertson, MM; Trimble, MR (February 1982). "The lateralising significance of hypergraphia in temporal lobe epilepsy". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 45 (2): 131–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.45.2.131. PMC 1083040. PMID 7069424.

- ^ Aminoff, Michael (2001). Neurology and General Medicine. p. 579.

- ^ a b c Flaherty, AW (March 2011). "Brain illness and creativity: mechanisms and treatment risks". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 56 (3): 132–43. doi:10.1177/070674371105600303. PMID 21443820.

- ^ Sachdev, H S; Waxman, S G (1981). "Frequency of hypergraphia in temporal lobe epilepsy: an index of interictal behaviour syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 44 (4): 358–60. doi:10.1136/jnnp.44.4.358. PMC 490963. PMID 7241165.

Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy tended to reply more frequently to a standard questionnaire, and wrote extensively (mean: 1301 words) as compared to others (mean: 106 words). The incidence of temporal lobe epilepsy was 73% in patients exhibiting hypergraphia compared to 17% in patients without this trait. These findings suggest that hypergraphia may be a quantitative index of behaviour change in temporal lobe epilepsy.

- ^ Flaherty, Alice W (December 28, 2012). "Writing and Drugs". Writing and Pedagogy. 4 (2): 191–207. doi:10.1558/wap.v4i2.191. ISSN 1756-5847.

- ^ van Vugt P, Paquier P, Kees L, Cras P (November 1996). "Increased writing activity in neurological conditions: a review and clinical study". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 61 (5): 510–4. doi:10.1136/jnnp.61.5.510. PMC 1074050. PMID 8937347.

- ^ a b Jamison, Kay R. (1994). Touched with fire: manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament (1. paperback ed.). New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-916003-9.

- ^ Carson, Shelley H.; Peterson, Jordan B.; Higgins, Daniel M. (September 2003). "Decreased latent inhibition is associated with increased creative achievement in high-functioning individuals". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 85 (3): 499–506. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.499. ISSN 0022-3514. PMID 14498785.

- ^ a b Wicklund S, Wright M (2012). "Donepezil-induced mania". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 24 (3): E27. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11070160. PMID 23037669.

- ^ a b Planton S, Jucla M, Roux FE, Démonet JF (2013). "The 'handwriting brain': A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies of motor versus orthographic processes". Cortex. 49 (10): 2772–87. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2013.05.011. PMID 23831432. S2CID 22404108.

- ^ Shah C, Erhard K, Ortheil HJ, Kaza E, Kessler C, Lotze M (May 2013). "Neural correlates of creative writing: an fMRI study". Hum Brain Mapp. 34 (5): 1088–101. doi:10.1002/hbm.21493. PMC 6869990. PMID 22162145.

- ^ van Elst LT, Krishnamoorthy ES, Bäumer D, et al. (June 2003). "Psychopathological profile in patients with severe bilateral hippocampal atrophy and temporal lobe epilepsy: evidence in support of the Geschwind syndrome?". Epilepsy & Behavior. 4 (3): 291–7. doi:10.1016/s1525-5050(03)00084-2. PMID 12791331. S2CID 34974937.

- ^ Ishikawa, T; Saito, M; Fujimoto, S; Imahashi, H (September 2000). "Ictal increased writing preceded by dysphasic seizures". Brain & Development. 22 (6): 398–402. doi:10.1016/s0387-7604(00)00163-7. PMID 11042425. S2CID 43906342.

- ^ Imamura, T; Yamadori, A; Tsuburaya, K (January 1992). "Hypergraphia associated with a brain tumour of the right cerebral hemisphere". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 55 (1): 25–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.55.1.25. PMC 488927. PMID 1548492.

- ^ a b Brownlee 2006.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1969). Nightfall, and other stories. Doubleday. p. 244.

- ^ "New Comments on the Epilepsy of Fyodor Dostoevsky," Epilepsia 25 (No. 4, 1984), p. 409.

- ^ Robert Burns and the Medical Profession Retrieved : January 11, 2014

- ^ Flaherty, The Midnight Disease p 26

Further reading

[edit]- Flaherty, Alice Weaver (2004). The Midnight Disease: The Drive to Write, Writer's Block, and the Creative Brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-23065-3.

- Pickover, C. A. (1999). Strange brains and genius: The secret lives of eccentric scientists and madmen. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-16894-9

- Schachter, S. C., Holmes, G. L., & Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité, D. (2008). Behavioral aspects of epilepsy: Principles and practice. New York: Demos. ISBN 1-933864-04-4