Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Supraesophageal ganglion

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

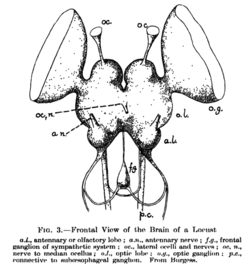

The supraesophageal ganglion (also supraoesophageal ganglion, arthropod brain, or microbrain[1]) generally consists of a set of three fused pairs of ganglia, which constitute the brain in most insect species and in some other closely related arthropods, such as myriapods and crustaceans. It receives and processes information from the first, second, and third metameres. The supraesophageal ganglion lies dorsal to the esophagus and consists of three parts, each a pair of ganglia that may be more or less pronounced, reduced, or fused depending on the genus:

- The protocerebrum, associated with the eyes (compound eyes and ocelli).[2] Directly associated with the eyes is the optic lobe, as the visual center of the brain.

- The deutocerebrum processes sensory information from the antennae.[2][3] It consists of two parts, the antennal lobe and the dorsal lobe.[3][4][5] The dorsal lobe also contains motor neurons which control the antennal muscles.[6]

- The tritocerebrum integrates sensory inputs from the previous two pairs of ganglia.[2] The lobes of the tritocerebrum split to circumvent the esophagus and begin the subesophageal ganglion.

The subesophageal ganglion continues the nervous system and lies ventral to the esophagus. Finally, the segmental ganglia of the ventral nerve cord are found in each body segment as a fused ganglion; they provide the segments with some autonomous control.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Makoto Mizunami, Fumio Yokohari, Masakazu Takahata (1999). "Exploration into the Adaptive Design of the Arthropod "Microbrain"". Zoological Science. 16 (5): 703–709. doi:10.2108/zsj.16.703. S2CID 86501328.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Meyer, John R. "The Nervous System". General Entomology course at North Carolina State University. Department of Entomology NC State University. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b Homberg, U; Christensen, T A; Hildebrand, J G (1989). "Structure and Function of the Deutocerebrum in Insects". Annual Review of Entomology. 34: 477–501. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.34.010189.002401. PMID 2648971.

- ^ "Invertebrate Brain Platform". RIKEN BSI Neuroinformatics Japan Center.

- ^ "Deutocerebrum". Flybrain.

- ^ "Deutocerebrum". Invertebrate Brain Platform. Chelicerata, with their missing antennae, have a very reduced (or absent) deutocerebrum.

Further reading

[edit]- Erber, J.; Menzel, R. (1977). "Visual interneurons in the median protocerebrum of the bee". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 121 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1007/bf00614181. S2CID 34198518.

- Wong, Allan M., Jing W. Wang, and Richard Axel (2002). "Spatial Representation of the Glomerular Map in the Drosophila Protocerebrum". Cell. 109 (2): 229–241. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00707-9. PMID 12007409.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Malun, D.; Waldow, U.; Kraus, D.; Boeckh, J. (1993). "Connections between the deutocerebrum and the protocerebrum, and neuroanatomy of several classes of deutocerebral projection neurons in the brain of male Periplaneta americana". J. Comp. Neurol. 329 (2): 143–162. doi:10.1002/cne.903290202. PMID 8454728. S2CID 20142144.

- Flanagan, Daniel; Mercer, Alison R. (1989). "Morphology and response characteristics of neurones in the deutocerebrum of the brain in the honeybeeApis mellifera". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 164 (4): 483–494. doi:10.1007/bf00610442. S2CID 23327875.

- Childress, Steven A.; B. McIver, Susan (1984). "Morphology of the deutocerebrum of female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 62 (7): 1320–1328. Bibcode:1984CaJZ...62.1320C. doi:10.1139/z84-190.

- Technau, Gerhard (2008). Technau, Gerhard M (ed.). Brain Development in Drosophila melanogaster. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (in Dutch). Vol. 628. New York Austin, Tex: Springer Science+Business Media Landes Bioscience. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-78261-4. ISBN 978-0-387-78260-7. OCLC 314349837.

- Aubele, Elisabeth, and Nikolai Klemm (1977). "Origin, destination and mapping of tritocerebral neurons of locust". Cell and Tissue Research. 178 (2): 199–219. doi:10.1007/bf00219048. PMID 66098. S2CID 22872816.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chaudonneret, J. "Evolution of the insect brain with special reference to the so-called tritocerebrum." Arthropod brain. Wiley, New York (1987): 3-26.

- "Behavioral Neuroscience, lecture on Honey Bee and its behavior - Neuroanatomy". Retrieved 2019-02-08.

External links

[edit]- "Suboesophageal Ganglion". flybrain.

- "Dissecting insect brain for in vivo electrophysiology". YouTube. Neuronal Systems Lab, Center for Neural and Cognitive Systems, University of Hyderabad. 27 June 2021.