Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Server (computing).

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Server (computing)

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Server (computing)

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

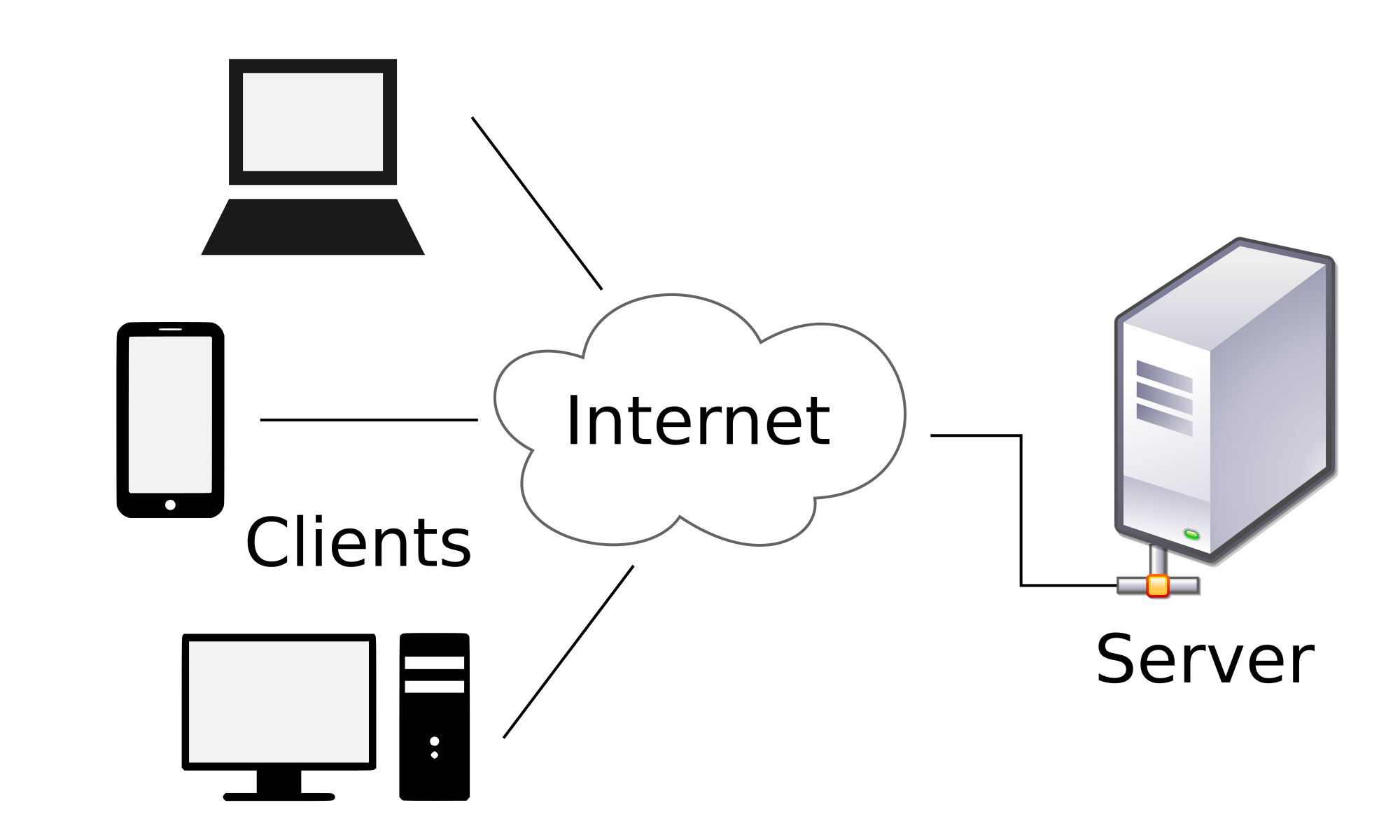

In computing, a server is a computer or device on a network that manages resources and provides services to other computers or devices, known as clients, such as file, print, database, or network management functions.[1] Servers operate within the client-server model, where clients initiate requests for data or services, and servers respond by delivering the required functionality, often across local or wide-area networks.[2] This architecture enables centralized resource management, scalability for handling multiple simultaneous requests, and efficient distribution of computing tasks.[3]

Servers can function as dedicated hardware systems optimized for reliability, high performance, and continuous operation, featuring powerful processors, substantial memory, redundant storage, and advanced cooling to support demanding workloads without frequent interruptions.[4] Common types include web servers for hosting websites, database servers for data storage and retrieval, email servers for message handling, and application servers for executing business logic, each tailored to specific network roles.[5] Evolving from mainframe systems in the mid-20th century—rooted in queueing theory for service provision—the modern server traces key milestones like the first web server in 1990 and rack-mounted designs in 1993, which facilitated data center deployments and the internet's expansion.[6] These systems underpin essential infrastructure for enterprises, cloud computing, and global connectivity, prioritizing uptime, security, and efficiency over user interactivity found in client devices.[7]

Servers incorporate network interface controllers (NICs) as primary hardware for connectivity, enabling communication over Ethernet networks via physical ports such as RJ-45 for copper cabling or SFP+ for fiber optics.[61][62] These interfaces support speeds ranging from 1 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) in legacy systems to 25 GbE and 100 GbE in contemporary data center deployments, where 25 GbE serves as a standard access speed for many enterprise servers due to cost-effectiveness and sufficient bandwidth for most workloads.[63] Higher-speed uplinks, such as 400 GbE and emerging 800 GbE, are increasingly adopted in hyperscale environments to handle escalating data traffic, projected to multiply by factors of 2.3 to 55.4 by 2025 according to IEEE assessments.[64][65] Specialized protocols like RDMA over Converged Ethernet facilitate low-latency data transfers critical for applications in high-performance computing and storage fabrics.[66] Server form factors dictate physical enclosure designs optimized for scalability, cooling, and space efficiency in varied operational contexts. Tower servers, akin to upright desktop cases, accommodate standalone or small-business setups with expandability for fewer than ten drives but consume more floor space and airflow compared to denser alternatives.[14] Rack-mount servers dominate data centers, adhering to the EIA-310-D standard for 19-inch-wide mounting in cabinets, where vertical spacing is quantified in rack units (U), with 1U equating to 1.75 inches in height to enable stacking of multiple units—typically 1U or 2U for compact, high-throughput models.[67][68] Blade servers enhance density by integrating compute modules into shared chassis that provide common power, networking, and cooling, reducing cabling complexity and operational overhead in large-scale clusters, though they demand compatible infrastructure investments.[69][70] These configurations prioritize causal trade-offs: rack and blade forms minimize latency through proximity and shared fabrics, while tower variants favor simplicity in low-density scenarios.[71]

Definition and Core Principles

Fundamental Purpose and Functions

A server constitutes a dedicated computing system engineered to deliver resources, data, services, or processing capabilities to client devices over a network. Its core purpose centers on fulfilling client-initiated requests by centralizing resource management, which facilitates efficient distribution, reduces hardware duplication across endpoints, and supports multi-user access to shared functionalities. This architecture underpins the client-server model, where servers operate continuously to ensure responsiveness and reliability, handling workloads that would otherwise overwhelm individual client machines.[4][8][9] Key functions encompass data storage and retrieval, whereby servers maintain persistent repositories accessible via standardized protocols; computation execution, performing intensive tasks like query processing or algorithmic operations delegated by clients; and resource orchestration, including load balancing to distribute demands across multiple units for sustained performance. Servers also enforce access controls and security measures to safeguard shared assets, while logging interactions for auditing and optimization. These operations enable applications such as web hosting, where servers respond to HTTP requests with dynamic content, or database management, querying structured data in real-time. Empirical metrics underscore efficiency: for instance, enterprise servers can process thousands of concurrent requests per second, far exceeding typical client hardware limits.[10][11][12] In essence, servers embody causal realism in networked computing by decoupling service provision from end-user devices, allowing specialization—servers prioritize uptime, redundancy via RAID configurations achieving 99.999% availability in data centers, and scalability through clustering—while clients focus on user interfaces and lightweight interactions. This division optimizes overall system throughput, as evidenced by the proliferation of server-centric infrastructures since the 1980s, which have scaled global internet traffic from megabits to exabytes daily.[4][8]Classifications and Types

Servers in computing are classified by hardware form factors, which determine their physical design and deployment suitability, and by functional roles, which define the primary services they deliver to clients. Hardware classifications include tower, rack, and blade servers, each optimized for different scales of operation from small businesses to large data centers.[13][14] Tower servers resemble upright personal computers with server-grade components such as redundant power supplies and enhanced cooling, making them suitable for standalone or small network environments where space is not a constraint and ease of access for maintenance is prioritized.[15] They typically support 1-4 processors and are cost-effective for entry-level deployments but less efficient for high-density scaling due to their larger footprint.[16] Rack servers are engineered to mount horizontally in standard 19-inch equipment racks, enabling modular expansion and efficient use of data center floor space through vertical stacking in units measured in rack units (U1U to U4U typically).[17] This form factor facilitates cable management, shared infrastructure, and rapid scalability, predominant in enterprise and cloud environments where thousands of servers may operate in colocation facilities.[13] Blade servers consist of thin, modular compute units—blades—that insert into a shared chassis providing power, cooling, and networking, achieving higher density than rack servers by minimizing per-unit overhead.[15] Each blade functions as an independent server but leverages chassis-level resources, ideal for high-performance computing clusters or virtualization hosts requiring intensive parallel processing.[16] Functionally, servers specialize in tasks such as web hosting, data management, and resource sharing. Web servers process HTTP requests to deliver static and dynamic content, with software like Apache HTTP Server handling over 30% of websites as of 2023 per usage surveys.[5][4] Database servers store, retrieve, and manage structured data using systems like MySQL or PostgreSQL, optimizing for query performance via indexing and transaction processing to support applications requiring ACID compliance.[18][19] File servers centralize storage for network-accessible files, employing protocols like SMB or NFS to enable sharing, versioning, and permissions control across distributed users.[3] Mail servers route electronic messages using SMTP for outbound transfer and IMAP/POP3 for retrieval, often incorporating spam filtering and secure transport via TLS.[5] Application servers execute business logic and middleware, bridging clients and backend resources in architectures like Java EE or .NET, facilitating scalable deployment of enterprise software.[18] Proxy servers act as intermediaries for requests, enhancing security through caching, anonymity, and content filtering.[4] DNS servers resolve domain names to IP addresses, underpinning internet navigation via recursive or authoritative query handling.[18] A single physical server may host multiple virtual instances via hypervisors like VMware or KVM, allowing diverse functional types to coexist on unified hardware for resource efficiency.[20]Historical Development

Early Mainframe Era (1940s–1970s)

The development of mainframe computers in the 1940s and 1950s laid the groundwork for centralized computing systems that functioned as early servers, processing data in batch mode for multiple users or tasks through punched cards or tape inputs. These machines, often room-sized and powered by vacuum tubes, prioritized reliability and high-volume calculations over interactivity, serving governmental and scientific needs before commercial expansion. The UNIVAC I, delivered to the U.S. Census Bureau on June 14, 1951, marked the first commercially available digital computer in the United States, weighing 16,000 pounds and utilizing approximately 5,000 vacuum tubes for data processing tasks such as census analysis.[21][22] Designed explicitly for business and administrative applications, it replaced slower punched-card systems with magnetic tape storage and automated alphanumeric handling, enabling faster execution of repetitive operations.[23][24] IBM emerged as a dominant force in the 1950s, producing machines like the IBM 701 in 1952, its first commercial scientific computer, which supported batch processing for engineering and research computations.[25] By the mid-1960s, the IBM System/360, announced on April 7, 1964, introduced a compatible family of six models spanning small to large scales, unifying commercial and scientific workloads under a single architecture that emphasized modularity and upward compatibility.[26][27] This shift to transistor-based third-generation mainframes reduced costs through economies of scale and enabled real-time processing for inventory and accounting, fundamentally altering business operations by allowing scalable data handling without frequent hardware overhauls.[28] Mainframe sales surged from 2,500 units in 1959 to 50,000 by 1969, reflecting their adoption for centralized data management in enterprises.[29] The 1960s brought time-sharing innovations, transforming mainframes into interactive servers capable of supporting multiple simultaneous users via remote terminals, a precursor to modern client-server dynamics. John McCarthy proposed time-sharing around 1955 as an operating system allowing users to interact as if in sole control of the machine, dividing CPU cycles rapidly among tasks to simulate concurrency.[30] The Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS), implemented at MIT in 1961, demonstrated this by enabling multiple users to access a central IBM 709 via teletype terminals, reducing wait times from hours in batch mode to seconds.[31] Systems like Multics, developed from 1964 at MIT, further advanced secure multi-user access and file sharing, influencing later operating systems despite its complexity.[32][33] By the 1970s, mainframes incorporated interactive terminals such as the IBM 2741 and 2260, supporting hundreds of concurrent users in time-sharing environments and paving the way for networked computing.[34] IBM's System/370 series, introduced in 1970, extended the System/360 architecture with virtual memory enhancements, boosting efficiency for enterprise workloads like banking and airlines reservations.[35] These evolutions prioritized fault-tolerant design and high I/O throughput, essential for serving diverse peripheral devices and establishing mainframes as robust central hubs in organizational computing infrastructures.[36]Emergence of Client-Server Model (1980s–1990s)

The client-server model emerged in the early 1980s amid the transition from centralized mainframe computing to distributed systems, driven by the affordability and capability of personal computers. Organizations began deploying networks to share resources like files and printers, reducing reliance on expensive terminals connected to mainframes. This shift was facilitated by advancements in networking hardware, including the IEEE 802.3 standard for Ethernet ratified in 1983, which standardized local area network communication.[37] A pivotal example was Novell NetWare, released in 1983, which introduced dedicated file and print servers accessible by PC clients over networks, marking one of the first widespread implementations of server-based resource management. Database technologies also advanced along client-server lines; Sybase, founded in 1984, developed an SQL-based architecture separating client applications from server-hosted data processing, enabling efficient query handling across distributed environments. These systems emphasized servers as centralized providers of compute-intensive tasks, while clients managed user interfaces and local processing.[38][39] By the late 1980s, the model gained formal acceptance in software architecture, with the term "client-server" describing the division of application logic between lightweight clients and robust servers. This period saw the rise of relational database management systems like Oracle's offerings, which by the 1990s supported multi-user client access to shared data stores. The proliferation of UNIX-based servers and protocols like TCP/IP further solidified the paradigm, laying groundwork for internet-scale applications in the 1990s, though initial focus remained on enterprise LANs.[40]Virtualization and Distributed Systems (2000s–Present)

The adoption of server virtualization in the 2000s transformed server computing by enabling the partitioning of physical hardware into multiple isolated virtual machines (VMs), thereby addressing inefficiencies from underutilized dedicated servers. VMware's release of ESX Server in 2001 introduced a type-1 hypervisor that ran directly on x86 hardware, allowing enterprises to consolidate workloads and achieve up to 10-15 times higher server utilization rates compared to physical deployments.[41] This shift reduced capital expenditures on hardware, as organizations could defer purchases of additional physical servers amid rising demands from web applications and data growth.[42] Open-source alternatives accelerated virtualization's proliferation; the Xen Project hypervisor, initially developed at the University of Cambridge, released its first version in 2003, supporting paravirtualization for near-native performance on commodity servers.[42] By 2006, VMware extended accessibility with the free VMware Server, while Linux-based KVM emerged in 2007 as an integrated kernel module, embedding virtualization into standard server operating systems like those from Red Hat and Ubuntu.[42] These technologies lowered barriers for small-to-medium enterprises, fostering hybrid environments where physical and virtual servers coexisted, though early challenges included overhead from VM migration and security isolation. Microsoft's Hyper-V, integrated into Windows Server 2008, further mainstreamed virtualization in Windows-dominated data centers, capturing significant market share by emphasizing compatibility with existing applications.[42] Virtualization laid the groundwork for distributed systems by enabling elastic scaling across networked servers, culminating in cloud computing's rise. Amazon Web Services (AWS) launched Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) in 2006, offering on-demand virtual servers backed by distributed physical infrastructure, which by 2010 supported over 40,000 instances daily and reduced provisioning times from weeks to minutes.[43] This model extended to multi-tenant environments, where hyperscale providers like Google and Microsoft Azure deployed thousands of interconnected servers for fault-tolerant distributed processing.[44] In distributed frameworks, virtualization complemented tools like Apache Hadoop (2006), which distributed data processing across clusters of virtualized commodity servers, handling petabyte-scale workloads through horizontal scaling rather than vertical upgrades.[45] The 2010s onward integrated containerization with virtualization for lighter-weight distributed systems, as containers—building on Linux kernel features like cgroups (2006) and namespaces (2000s)—allowed microservices to run efficiently across server clusters without full VM overhead. Docker's 2013 release popularized container packaging for servers, enabling rapid deployment in distributed setups, while Kubernetes (2014), originally from Google, provided orchestration for managing thousands of containers over dynamic server pools, achieving auto-scaling and self-healing in production environments.[46] By 2020, over 80% of enterprises used hybrid virtualized-distributed architectures, with edge computing extending these to geographically dispersed servers for low-latency applications.[45] Challenges persist in areas like network latency in hyper-distributed systems and energy efficiency, driving innovations in serverless computing where providers abstract server management entirely.[47]Hardware Components and Design

Processors, Memory, and Storage

Server processors, commonly known as CPUs, are designed for sustained high-throughput workloads, featuring multiple cores, sockets for scalability, and support for error-correcting code (ECC) memory to maintain data integrity under heavy loads. The x86 architecture dominates, with Intel's Xeon series and AMD's EPYC series leading the market; in Q1 2025, AMD achieved 39.4% server CPU market share, up from prior quarters, while Intel retained approximately 60%. [48] [49] ARM-based processors are expanding rapidly, capturing 25% of the server market by Q2 2025, driven by energy efficiency in hyperscale data centers and AI applications. [50] High-end models like the AMD EPYC 9755 offer 128 cores at up to 512 MB L3 cache, enabling parallel processing for databases and virtualization. [51] Server memory relies on ECC dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) modules, which detect and correct single-bit errors using parity bits—typically 8 check bits per 64 data bits—to prevent corruption in mission-critical environments. [52] [53] DDR4 and emerging DDR5 standards are prevalent, with registered DIMMs (RDIMMs) providing buffering for stability in multi-channel configurations supporting capacities from 16 GB to 256 GB per module. [54] [55] Systems can scale to several terabytes total, as evidenced by Windows Server 2025's support for up to 240 TB in virtualized setups, though physical limits depend on motherboard slots and CPU capabilities. [56] Storage in servers balances capacity, speed, and redundancy, often combining hard disk drives (HDDs) for economical bulk storage with solid-state drives (SSDs) and NVMe interfaces for low-latency I/O operations via PCIe lanes. [57] NVMe SSDs deliver superior performance over SATA SSDs or HDDs, with RAID configurations like RAID 10 offering striping and mirroring for enhanced throughput and fault tolerance, while RAID 5/6 prioritizes capacity with parity. [58] [59] Hardware RAID controllers are less common for NVMe due to direct PCIe attachment, favoring software-based redundancy to avoid performance bottlenecks. [60]Networking and Form Factors

Servers incorporate network interface controllers (NICs) as primary hardware for connectivity, enabling communication over Ethernet networks via physical ports such as RJ-45 for copper cabling or SFP+ for fiber optics.[61][62] These interfaces support speeds ranging from 1 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) in legacy systems to 25 GbE and 100 GbE in contemporary data center deployments, where 25 GbE serves as a standard access speed for many enterprise servers due to cost-effectiveness and sufficient bandwidth for most workloads.[63] Higher-speed uplinks, such as 400 GbE and emerging 800 GbE, are increasingly adopted in hyperscale environments to handle escalating data traffic, projected to multiply by factors of 2.3 to 55.4 by 2025 according to IEEE assessments.[64][65] Specialized protocols like RDMA over Converged Ethernet facilitate low-latency data transfers critical for applications in high-performance computing and storage fabrics.[66] Server form factors dictate physical enclosure designs optimized for scalability, cooling, and space efficiency in varied operational contexts. Tower servers, akin to upright desktop cases, accommodate standalone or small-business setups with expandability for fewer than ten drives but consume more floor space and airflow compared to denser alternatives.[14] Rack-mount servers dominate data centers, adhering to the EIA-310-D standard for 19-inch-wide mounting in cabinets, where vertical spacing is quantified in rack units (U), with 1U equating to 1.75 inches in height to enable stacking of multiple units—typically 1U or 2U for compact, high-throughput models.[67][68] Blade servers enhance density by integrating compute modules into shared chassis that provide common power, networking, and cooling, reducing cabling complexity and operational overhead in large-scale clusters, though they demand compatible infrastructure investments.[69][70] These configurations prioritize causal trade-offs: rack and blade forms minimize latency through proximity and shared fabrics, while tower variants favor simplicity in low-density scenarios.[71]