Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

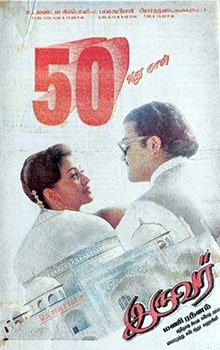

Iruvar

View on Wikipedia

| Iruvar | |

|---|---|

Poster | |

| Directed by | Mani Ratnam |

| Written by | Mani Ratnam |

| Dialogues by | |

| Poem by | |

| Produced by | Mani Ratnam G. Srinivasan |

| Starring | Mohanlal Prakash Raj Aishwarya Rai Revathi Tabu Gautami |

| Cinematography | Santosh Sivan |

| Edited by | Suresh Urs |

| Music by | A. R. Rahman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Madras Talkies |

Release date |

|

Running time | 158 minutes |

| Country | India |

| Language | Tamil |

Iruvar (transl. The Duo) is a 1997 Indian Tamil-language epic political drama film co-written, produced, and directed by Mani Ratnam. The film, inspired by the lives of M. G. Ramachandran, M. Karunanidhi and J. Jayalalithaa, is set against the backdrop of cinema and politics in Tamil Nadu. It stars Mohanlal with an ensemble supporting cast including Prakash Raj, Aishwarya Rai, Revathi, Gautami, Tabu, and Nassar. Rai, who was crowned Miss World 1994, made her first screen appearance, playing dual characters.

The high-budget film had its original soundtrack composed by A. R. Rahman, and the cinematography was by Santosh Sivan. The film marked Mohanlal's debut in Tamil cinema after having only a cameo in Gopura Vasalile.

Iruvar was the first Tamil film to be screened at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures on 19 April 2025[1] and was also screened at the Masters section in the 1997 Toronto International Film Festival. The film won the Best Film award at the Belgrade International Film Festival and two National Film Awards. In 2012, Iruvar was included by critic Rachel Dwyer in the 2012 British Film Institute Sight & Sound 1000 greatest films of all time.[2] In a 2013 interview, Ratnam said he considered Iruvar to be his best film. It used DTS 6 track sound recording.

Plot

[edit]In the late 1940s, Anandan, an aspiring actor, goes around studios in Madras trying to land roles. He meets Tamizhselvan, a rationalist writer he respects, steeped in Dravidian ideas. On the strength of Tamizhselvan's flowery writing and his own impassioned delivery, he is offered the title role in a few films.

Tamizhselvan introduces Anandan to Ayya Veluthambi, who leads a Dravidian political party. He grows to like the party's ideology. Anandan marries Pushpavalli, while Tamizhselvan marries Maragatham, from their respective villages. When the two return to Madras, Anandan's film has been cancelled due to financial difficulties. In a few months, Tamizhselvan's party becomes the main opposition party. Anandan is reduced to playing minor roles. He sends Pushpavalli back to their village and considers joining the army. A few days later, Pushpavalli dies from illness and Tamizhselvan consoles a despondent Anandan.

Weeks later, Anandan's fortunes return, and he is again offered the part of the protagonist. He convinces the director to hire Tamizhselvan as screenwriter. The film receives tremendous response upon release. Anandan becomes a celebrity and a major star in Tamil Cinema within a few years. During the next elections, Tamizhselvan encourages Anandan to use his popularity to help their party attract more attention. Anandan marries fellow actress Ramani who was being tortured by her own family. Five years later, Ayya Veluthambi asks Anandan to contest in the upcoming elections, though Tamizhselvan thinks there are many other devoted workers deserving candidacy.

Anandan is shot in neck by a prop gun while filming a scene, but the party sweeps elections, with 152 seats out of 234. Ayya Veluthambi refuses to become chief minister. He asks Anandan and another leader, Madhivannan, to decide who should be given the post. Tamizhselvan is resentful that Veluthambi did not involve him, but is chosen to be the chief minister of Tamil Nadu with Anandan's wholehearted support. Anandan later asks to be made the health minister, but Tamizhselvan refuses, on the pretext that the executive committee forbids ministers to continue acting while in office. He offers Anandan any portfolio of his choice on the condition that he suspend his acting career. Anandan does not take it up.

Senthamarai, who had admired Tamizhselvan's daring protests, moves in with him when he writes her a poetic letter and has a daughter with him. Anandan's co-star in his new film is Kalpana who resembles his late wife. While initially distant, Kalpana's chattiness draws Anandan to her. But still married to Ramani, his indecision about another marriage angers Kalpana because of which she leaves him.

In a memorial function on Ayya Veluthambi's death, Anandan claims party's corruption in governance was the cause of death of the former. Anandan's expulsion by Tamizhselvan splits the party, with several members creating a new one under Anandan's leadership.

Anandan uses his popular films for next four years to highlight corruption in Tamizhselvan's government and storms to power in the next election with 145/234 seats. But his governance turns out to be no different. Tamizhselvan's eloquent diatribes against misgovernance spark protests and Anandan orders his arrest with a heavy heart. Meanwhile, Anandan sees Kalpana at a disaster relief site and asks her to be brought. The car bringing her has an accident and Kalpana dies.

Anandan is distraught over Kalpana's death. At the wedding of Ayya Veluthambi's granddaughter, a visibly ailing Anandan meets Tamizhselvan. They share a handshake but hardly talk. The next morning, Ramani finds Anandan dead in his bed. Tamizhselvan, in an emotional monologue set in a place where the two had previously planned dominating the Tamil state, recites poetry mourning his death.

Cast

[edit]- Mohanlal as Anandan, a superstar actor, who later becomes the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu

- Prakash Raj as Tamizhselvan, the former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu and current opposition leader

- Aishwarya Rai as Pushpavalli and Kalpana

- Gautami as Ramani[3]

- Revathi as Maragatham

- Tabu as Senthamarai[3]

- Nassar as Ayya Veluthambi

- Kaka Radhakrishnan as Kasshi

- Major Sundarrajan as Police Officer[3]

- Rajesh as Madhivanan

- Delhi Ganesh as Nambi

- Nizhalgal Ravi as Ramani's uncle[3]

- Kalpana Iyer as Annamal, Anandan's mother[4]

- S. N. Lakshmi as Tamizhselvan's mother

- Gowtham Sundararajan as Elango

- C. K. Saraswathi

- P. L. Narayana as Ramasamy

- Laxmi Rattan as Arjun Doss

- Sujitha as Tamizhselvan's daughter

- Vishnuvardhan as Tamizhselvan's son

- Krishna Kulasekaran as Tamizhselvan's son

- Monica as Manimegalai, Tamizhselvan's daughter

- Cheenu Mohan as Assistant director

- Madhoo in a special appearance in song "Narumugaye"[3]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In October 1995, Mani Ratnam announced that he was set to make a feature film titled Anandan featuring dialogue written by his wife Suhasini and starring Mohanlal, Nana Patekar, and Aishwarya Rai.[5] Initial speculation suggested that the film would visualise the duel between Velupillai Prabhakaran and his former Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam deputy Mahattaya, who was executed in 1995 for an alleged plot to kill his mentor, with Aishwarya Rai reported to be playing Indira Gandhi.[6] Mani Ratnam was quick to deny any political backdrop claiming that the film would be about the Indian movie industry; however, this proved to bluff the public as the film was to be set within a political canvas. The film was later retitled Iruvar (The Duo). The idea to make a film on the lives of 1980s Tamil Nadu political icons M. G. Ramachandran and M. Karunanidhi and their influential relationship between Tamil cinema and Dravidian politics was sparked off by a conversation Mani Ratnam had with renowned Malayalam author, M. T. Vasudevan Nair.[7]

Casting

[edit]When interviewed about the difficulties of casting, Mani Ratnam revealed he "struggled" citing that casting "is most important as far as performance is concerned" and that "fifty per cent of the job is done if you cast correctly".[7] Mohanlal was approached to play Anandan, a character inspired by M. G. Ramachandran and about his performance in the film, Ratnam claimed that Mohanlal had "the ability to make everything absolutely realistic with the least amount of effort". He described that debutant Aishwarya Rai, the former Miss World beauty pageant winner, who appeared in two different characters—one inspired by actress-politician J. Jayalalithaa—as a "tremendous dancer" and as "having a lot of potential". The director revealed that the only difficulty Mohanlal and Rai had was the language, with both being non-Tamil speakers, adding that the pair had to work hard over the dubbing trying to get as close to the Tamil tongue as possible.[7] Tabu was also signed to play an important role in the film and shot for Iruvar alongside her Tamil debut film, Kadhal Desam.[8]

The actor to play the role of Tamizhselvan, inspired by Karunanidhi, took substantially longer to finalise with the initial choice, Nana Patekar, withdrawing after several discussions about his remuneration. Later, Mammootty was offered the role but declined, as did Kamal Haasan and Sathyaraj.[9][10] Negotiations with R. Sarathkumar failed as he demanded a higher remuneration, and Mithun Chakraborty declined as the required looks would have affected his other film commitments. Arvind Swamy was later signed on,[11] but soon opted out after a look test, as he could not cut his hair for the role, which would have caused continuity problems for his commitment to Minsara Kanavu and Pudhayal (1997).[12] Ratnam called R. Madhavan, then a small-time model, for the screen test, but left him out of the project citing that he thought his eyes looked too young for a senior role.[13][14][15] Subsequently, Prakash Raj, who had played a small role in Ratnam's Bombay (1995), was signed up. Prakash Raj initially told Ratnam that he was unprepared to essay such a delicate role on such short notice, with Prakash Raj later revealing that Ratnam nurtured the character and brought self-confidence into the actor.[9]

Filming

[edit]The film was shot in 1996 and schedules were canned all across India from Kerala to Leh with Mohanlal stating that it was the longest duration he had shot for a film.[16] To ensure perfection, Ratnam made Prakash Raj take 25 takes for his first shot, lasting over six hours. After the shooting for Iruvar was completed, Mani Ratnam asked Prakash Raj to dub in Tamil himself for the first time, with his work taking four days to complete.[9]

Soundtrack

[edit]The soundtrack was composed by A. R. Rahman.[17] It has songs ranging from pure Carnatic to Tamil folk and jazz. Rahman blended two Carnatic ragas—Naattai and Gambheera Naattai—in "Narumugaye".[18] "Vennila Vennila" and "Hello Mister Edhirkatchi" are based on jazz music.[19][20] Rahman sampled Dave Grusin's "Memphis Stomp" for the intro of "Hello Mister Edhirkatchi".[21] "Udal Mannukku" and "Unnodu Naan Irundha" were recitals by Arvind Swamy.[22] Vishwa Mohan Bhatt also worked on the album, playing the Mohan veena upon Rahman's invitation.[23]

All lyrics are written by Vairamuthu, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Ayirathil Naan Oruvan" | Mano, A. R. Rahman (backing vocals) | 5:51 |

| 2. | "Narumugaye" | P. Unnikrishnan, Bombay Jayashri | 6:20 |

| 3. | "Kannai Kattikolathey" | Hariharan | 5:10 |

| 4. | "Vennila Vennila" (Lyricist:Vaali) | Asha Bhosle | 4:59 |

| 5. | "Hello Mister Edhirkatchi" | Harini, Rajagopal | 4:12 |

| 6. | "Pookodiyin Punnagai" | Sandhya Jayakrishna | 5:31 |

| 7. | "Udal Mannuku" | Arvind Swamy | 2:54 |

| 8. | "Unnodu Naan Irundha" | Arvind Swamy | 2:35 |

All lyrics are written by Veturi Sundararama Murthy, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Aadhukonadam Vratha Mai" | Mano | 5:51 |

| 2. | "Sasivadane" | P. Unnikrishnan, Bombay Jayashri | 6:22 |

| 3. | "Kallagganthalu Kattadhoi" | Hariharan | 5:56 |

| 4. | "Vennelaa" (Lyrics by Sirivennela Seetharama Sastry) | Asha Bhosle | 4:58 |

| 5. | "Hello Mister Edurpakshi" | Harini, Rajagopal | 4:13 |

| 6. | "Poonagave" | Sandhya Jayakrishna | 5:31 |

| 7. | "Odalu Mannanta" | Mano | 2:54 |

| 8. | "Unnanu Neeku Thodugaa" | S. P. Balasubrahmanyam, Dominique Cerejo | 2:36 |

Release

[edit]The Central Board of Film Certification panel saw the film on 31 December 1996 and opined that various characters in the film reflected the personal lives of some politicians and accordingly a certificate was denied. Following the producer's protest, it was seen by an eight-member revising committee on 2 January 1997 which suggested deletion of some objectionable portions and cleared the film for U/A certification. Four dialogues from the film were subsequently cut.[24] However the objected scenes were muted with a background playing rather than a complete muting of the scenes.

Two days before the release of the film, Dravidar Kazhagam president K. Veeramani threatened to mobilise public against its screening in theatres, because he felt that it contained "objectionable" footage denigrating the Dravidian movement founded by Periyar.[25] The politician threatened legal action if the film was screened in theatres without removing what he perceived as the "offending" portion, but Mani Ratnam dismissed that Veeramani was making rushed conclusions without having seen the film.[25] The film's box office performance was also hampered by the fallout from the FEFSI strike of 1997.[26]

A month after the film's release in February 1997, the regional chief of the censor board G. Rajasekaran brought up the issue again and referred the film to the Indian Home Office for "advice", threatening that if more scenes were not deleted, it might ultimately lead to a law and order problem.[24] The film was dubbed in Telugu under the title Iddaru and in Malayalam under the same name.[27][28]

Reception

[edit]The film received positive reviews from critics including by reviewers in Kalki,[29] The Hindu,[30] and the Edmonton Sun.[31]

Controversy

[edit]Both M. Karunanidhi and J. Jayalalithaa denied the relevance of the film to their lives and never admitted to the film being a biopic.[32]

Legacy

[edit]Mani Ratnam named Iruvar as his best film in an interview with critic Baradwaj Rangan.[33] Rangan also named the film the best work of Mani Ratnam, in his list “All Mani Ratnam Movies Ranked”.

The film was also noted for its vignette style of making, with many single-shot scenes, where a fluid camera setup captures the entire action.

Accolades

[edit]- International honours

- Belgrade International Film Festival – Best Film in the Festival of the Auteur Films

- Toronto International Film Festival – Masters section[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Museum, Academy (7 March 2025). "Emotion in Color: A Kaleidoscope of Indian Cinema".

- ^ "Duo, The". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Rangan 2012, p. 292.

- ^ Rangan 2012, p. 174.

- ^ Jayanthi (15 October 1995). "What makes Mani ?". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Paneerselvam, A. V. (14 February 1996). "With A Sepia Edge". Outlook. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Umashankar, Sudha (1998). "Films must reflect the times you live in". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Taliculam, Sharmila (4 April 1997). "Commercial films can get you only so far". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d Ramanujam, D. S (8 June 1999). "Power packed performance". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Rangarajan, Malathi (28 January 2012). "Character Call". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Sitaraman, Sandya (22 October 1996). "Kuzhappam.. shandai niraindha "Anandham"". Google Groups. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Thangadurai, S. (1997). "Look who's talking now". Filmfare. Archived from the original on 3 May 1999. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "A Close Shave". Outlook. 24 July 1996. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Ganapati, Priya (8 March 2000). "People remember scenes, not episodes". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Sitaraman, Sandya (3 February 1996). "Arvind Swamy-in pudhiya image!." Google Groups. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ Warrier, Shobha (4 April 1997). "I celebrate whether a film is a hit or a flop". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Iruvar Tamil audio cassette By A. R. Rahman". Banumass. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Mani, Charulatha (20 December 2013). "Versatile Nattai". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Desikan, Aparna (30 April 2015). "What Does it Take to Jazz Up?". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "10 lesser-known AR Rahman songs you should have been listening to this entire time". Vogue India. 8 October 2019. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Karthik (2 June 2012). "Blast from the past: Mani Rathnam – Sounds of success". Milliblog. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Roshmila (23 September 2021). "Revealed: Why Arvind Swamy Quit Films". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Taliculam, Sharmila (4 April 1997). ""Pop is temporary, classical music is permanent"". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2000. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Censors refer Iruvar to home dept". The Times of India. 28 February 1998. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ a b "Maniratnam's film 'Iruvar' draws DK leader's anger". The Times of India. 13 January 1998. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Strike paralyses Madras film industry". Rediff.com. 18 June 1997. Archived from the original on 16 June 2000. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Remembering S P Balasubrahmanyam: 4 Telugu-dubbed movies that prove he was a brilliant voice actor". 25 September 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "24 Years of Iruvar: A nostalgic look-back at Mani Ratnam's ode to TN politics; 50+ lesser-known facts & rare working stills". Cinema Express. 16 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ ஆர். பி. ஆர். (26 January 1997). "இருவர்". Kalki (in Tamil). p. 16. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Hindu's Iruvar Review". The Hindu. 24 January 1997. Archived from the original on 5 March 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Tilley, Steve (11 March 1998). "Friends at odds in fine Tamil Tale". Edmonton Sun. Archived from the original on 15 July 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Narayanan, Sujatha (7 December 2016). "How Mani Ratnam's Iruvar put the spotlight on Jaya". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Rangan 2012, p. 182.

- ^ Dhananjayan 2014, p. 365.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dhananjayan, G. (2014). Pride of Tamil Cinema: 1931–2013. Blue Ocean Publishers. OCLC 898765509.

- Rangan, Baradwaj (2012). Conversations with Mani Ratnam. India: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-08520-0.

External links

[edit]Iruvar

View on GrokipediaIruvar (transl. The Duo) is a 1997 Indian Tamil-language epic political drama film co-written, produced, and directed by Mani Ratnam.[1]

The narrative centers on the evolving relationship between two friends—one a dedicated theatre practitioner aspiring to cinema, the other a scriptwriter drawn into politics—whose ambitions lead to ideological conflict and personal estrangement, loosely inspired by the historical interplay between Tamil Nadu leaders M. G. Ramachandran and M. Karunanidhi.[2][3]

Featuring Mohanlal as the actor Anantha Neelakandan, Prakash Raj as the writer-politician Tamizhselvan, Aishwarya Rai Bachchan in her film debut as Pushpavalli, and supporting roles by Gautami and Nassar, the film examines themes of loyalty, power, and the intersection of art and politics in mid-20th-century Tamil society.[1][4]

Cinematography by Santosh Sivan and music by A. R. Rahman contributed to its artistic distinction, earning National Film Awards for Best Supporting Actor (Prakash Raj) and Best Cinematography, alongside the Best Film honor at the Belgrade International Film Festival.[5]

Critically lauded for its nuanced storytelling and technical excellence, Iruvar achieved strong retrospective appreciation despite modest box-office returns, cementing its status as a benchmark in Mani Ratnam's oeuvre for blending personal drama with socio-political commentary.[6]