Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Hagiography.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hagiography

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Hagiography

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

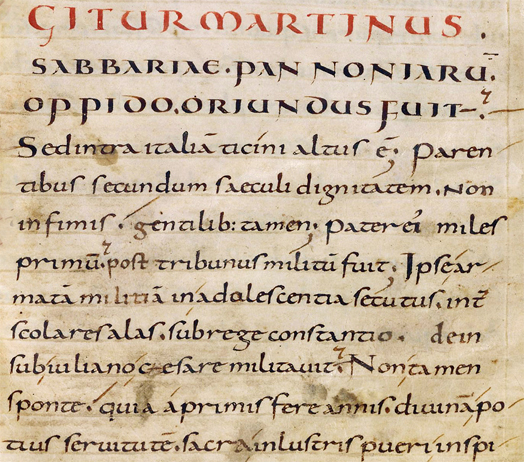

Hagiography, derived from the Greek terms hagios (holy) and graphē (writing), is a genre of Christian literature focused on the lives, deeds, miracles, and posthumous cults of saints. In modern usage, the term has also come to refer more broadly to any biography that idealizes or uncritically praises its subject.[1] These narratives, often termed vitae (lives) or passiones (accounts of suffering or martyrdom), blend historical elements with legendary motifs to portray saints as moral and spiritual exemplars for the faithful.[2] While primarily associated with Christianity, similar traditions exist in other religions, such as Judaism, where hagiographic accounts emphasize divine relationships and visible holiness.[3]

The origins of hagiography trace back to the early Christian period, with the earliest known texts emerging in the 2nd century CE, such as passion narratives of martyrs.[4] It proliferated during late antiquity and reached its peak in the Middle Ages, particularly in Western and Eastern Christendom, where it became a dominant literary form for promoting saint cults and theological doctrines.[5] In the Byzantine Empire, for instance, hagiographic production surged from the 8th to 10th centuries, often serving as vehicles for defending icon veneration during periods of iconoclasm or commemorating monastic figures through miracle collections and relic translations.[5] By the 13th century, the Roman Catholic Church centralized the canonization process under papal authority, influencing the standardization of saintly narratives.[4]

Hagiographies differ from secular biographies by prioritizing edification over factual accuracy, employing recurring literary topoi—such as ascetic trials or divine interventions—to convey virtues like humility and piety.[4] They offer historians critical windows into medieval social structures, including gender dynamics (where female saints were often underrepresented due to clerical biases), provincial life, and material culture, despite their propagandistic elements.[5] The scholarly study of hagiography emerged in the 17th century through the Bollandists, a group of Jesuit scholars who compiled and critically analyzed saints' lives in the multi-volume Acta Sanctorum, establishing rigorous philological methods that continue to underpin the field.[4] Today, hagiography remains a vital resource for understanding religious history, with ongoing projects like digital databases facilitating access to Byzantine and medieval texts.[5]