Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

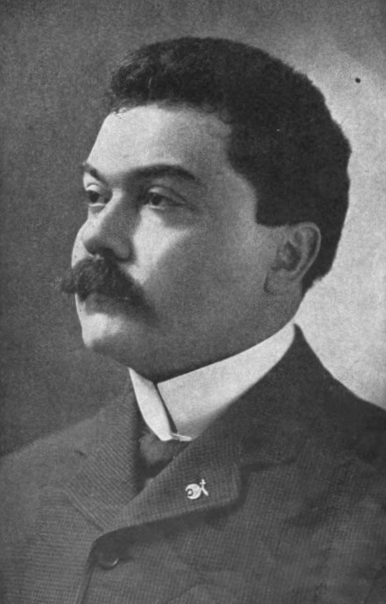

John Ringling

View on Wikipedia

John Nicholas Ringling (May 31, 1866 – December 2, 1936) was an American entrepreneur who is the best known of the seven Ringling brothers, five of whom merged the Barnum & Bailey Circus with their own Ringling Bros. World's Greatest Shows to create a virtual monopoly of traveling circuses and helped shape the modern circus. In addition to owning and managing many of the largest circuses in the United States, he was also a rancher, a real estate developer and art collector.[1] He was inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame in 1987.[2]

Key Information

Early circus life

[edit]

John was born in McGregor, Iowa, the fifth son in a family of seven sons and a daughter born to a French mother, Marie Salomé Juliar, and German father, August Ringling (a farmer and harness maker). The original family name was "Ruengeling". Five of those sons worked together to build a circus empire.[3]

The Ringlings started their first show in 1870 as "The Ringling Bros. United Monster Shows, Great Double Circus, Royal European Menagerie, Museum, Caravan, and Congress of Trained Animals", charging a penny for admission. In 1882, it was known as "The Ringling Bros. Classic and Comic Concert Company". By 1889, the circus was large enough to travel on railroad cars, rather than animal-drawn wagons. [citation needed]

In 1905, John married Mable Burton. In 1907, the brothers bought the Barnum & Bailey circus for $400,000 from the estate of James Anthony Bailey and ran the two circuses as separate entities until the end of the 1918 season.[4] John worked the circus with his brothers, declaring "We divided the work; but stood together." John took the advance position, traveling ahead and booking the appearances and Charles was the operating manager.[citation needed]

Building the circus empire

[edit]

After purchasing Barnum & Bailey's Greatest Show on Earth from the estate of James Bailey in 1907, the Ringling brothers were recognized as the "Circus Kings" in the United States as they controlled not only the show that carried their own name, but also the Barnum & Bailey circus and the Adam Forepaugh and Sells Brothers Circus.[5]

In the early 1900s the ranks of the brothers began thinning as Otto died unexpectedly in 1911. Four years later, the oldest sibling, Al Ringling also died, followed by brother Henry in 1918. At the same time that family management was evolving, the Ringlings were challenged by keeping two mammoth circuses touring during World War I. Manpower shortages, combined with railroad restrictions and the 1918 flu pandemic all contributed in the decision to merge the Ringling Bros World's Greatest Shows and the Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth at the end of the 1918 season.[6] On October 8, 1918, the Ringling Bros. season concluded after performances in Waycross, Georgia, and the circus trains were routed to the Barnum & Bailey Winter Quarters in Bridgeport, Connecticut.[7] During the winter of 1918-19 the two circuses were combined into one enormous show,[8] and on March 29, 1919, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus debuted at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

After the death of Alf T. Ringling in 1919, brothers John and Charles made the decision to move the Winter Quarters to Sarasota, Florida, in 1927[9] where the brothers were having success in real estate speculation.[10] Although a resident of Sarasota, Charles died in 1926 before the move was complete. With the death of brother Charles, John was now the last of the Ringling brothers. Although other family members had inherited stock in the company, as President he continued to manage the circus in the years prior to The Great Depression.[11]

During the 1920s, Ringling built Gray Crag, a 20-room manor house on an estate that was their summer residence in Alpine, New Jersey, atop the New Jersey Palisades and overlooking the Hudson River. Ringling would bring the circus troupe across the river from Yonkers, New York, with acrobats and animals to entertain their guests at parties. With the financial and personal difficulties that Ringling faced during the Great Depression, control of the property was lost and the house was ultimately demolished in November 1935.[12][13]

In 1909 John and his wife, Mable began spending their winters in Sarasota. The couple bought bay front property from Mary Louise and Charles N. Thompson, another circus manager who engaged several members of the Ringling family in land investments on the Florida Gulf Coast. Ringling commissioned a 30-room mansion which was inspired by the Venetian Gothic palaces, designed by New York architect Dwight James Baum, and built by Owen Burns, It was completed in 1926 and named Cà d'Zan, "The House of John" in Venetian. Later a museum was built on the grounds of the estate for their art collection. Because of their investments in real estate and the later development of the circus winter quarters as a tourist attraction, John and his brother, Charles are seen as pioneers in the development of Sarasota.[14] After some 40 years in the entertainment business, along with his ownership of railroads, oil field and ranches John had become one of the richest men in the world.[15] In addition he was a world traveler as he was always looking for new acts for his circus. It was during these travels to Europe that he began establishing a collection of old world masterpieces and a collection of Baroque art[16] including four cartoons for tapestries by Peter Paul Rubens.[17]

In 1929, John Ringling bought the American Circus Corporation, which consisted of the Sells-Floto Circus, the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, the John Robinson Circus, the Sparks Circus, Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, and the Al G. Barnes Circus. He bought them from Jerry Mugivan, Bert Bowers, and Ed Ballard, for $1.7 million (approximately $31,130,000 today).[18] With that acquisition, Ringling owned all of the major traveling circuses in America.[19]

In 1933, the last of the Brothers Ringling, ill and aging John, who had owned more circuses than any other man on earth and whose fortune was once estimated to be $50,000,000, hobbled into a Federal Court in Brooklyn to testify on the loan that brought him low. The firm that held his note was in bankruptcy. At a prize fight in 1929, Mr. Ringling related, he met William M. Greve, president of New York Investors, Inc. (realty), who agreed to lend him $1,700,000. As collateral Mr. Ringling put up one-half of all his circus stocks. Shortly afterward New York Investors sold the Ringling note to the now bankrupt subsidiary. While ill last year, Mr. Ringling had been unable to meet an interest payment of about $18,000. Financier Greve promptly marched out to Coney Island. Threatening to attach the circus receipts, Financier Greve demanded: "Put all your assets in a bag and give them to me."

That night, despite a fever of 104, Mr. Ringling was put in a wheelchair and brought to another room. Over the protest of his nurse he signed papers which gave most of his assets to New York Investors. Later he learned that swift Mr. Greve had formed a voting trust to hold the Ringling stocks and manage the circuses, another trust to hold some of the Titians, Rembrandts, Hals, Rubens from his famed collection in Sarasota, Fla. Mr. Ringling was left with nothing. But he was one of the five voting trustees, and as soon as he could pay off the loan he would get his bag of assets back.[20]

Other businesses and activities

[edit]Ringling was involved in many businesses, including; railroads in Missouri, Montana, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Texas; oil in Oklahoma; real estate in Florida.[3][21]

- Chatham and Phenix National Bank of New York, director and shareholder.[22][23]

- Eastland, Wichita Falls and Gulf Railroad, from Mangum to Breckwalker.[24]

- John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, founder, Sarasota, Florida.[21]

- John Ringling Real Estate Company, president, Sarasota.[21]

- Kansas City, Mexico, and Orient Railroad Company, director.[25]

- Madison Square Garden Corporation, vice-president, and chairman of the board.[21][22]

- Madison Square Garden Sporting Company, president.[22]

- Oklahoma, New Mexico and Pacific Railway (nicknamed the Ringling Railroad); president and financier. Chartered January 8, 1913, sold to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) in 1926. Jake L. Hamon was the operator and Ringling's business agent for the railroad.[22][26][27][28]

- Ringling and Oil Fields Railway, president. Chartered November 23, 1916, leased to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in July, 1925, and sold to the AT&SF in 1926.[22][27]

- White Sulphur Springs and Yellowstone Park Railway, president.[29]

Namesakes

[edit]- Ringling, Montana, was named for John Ringling,[30] who at one time was president of the White Sulphur Springs and Yellowstone Park Railway.[29] John Ringling had a family summer home in White Sulphur Springs and purchased the hot springs there with the intent of building a resort spa and $1 million dollar 220-room hotel.[31]

- Ringling, Oklahoma, also named for Ringling, when the Oklahoma, New Mexico and Pacific Railway created the town.[26]

- The World War II Liberty Ship SS John Ringling was named in his honor.

- John Ringling Causeway, a road bridge in Sarasota, Florida, over Sarasota Bay connecting Sarasota to Lido Key and Longboat Key. Ringling lived in Sarasota during summers for many decades. Ringling had built the first bridge, in 1925. The current bridge is now the third one (the first one was replaced in 1950, the second one in 2000).

Decline in later life

[edit]Ringling's health soon began to fail and the Great Depression (which gripped the nation almost as soon as he acquired the American Circus Corporation) dealt a severe financial blow to the John Ringling empire. He lost virtually his entire fortune, but was able to retain his home, the museum and his extensive art collection. His wife, Mable, died in June 1929 and he remarried on June 19, 1930, to Emily Haag Buck in Jersey City, New Jersey.[32]

Ringling was voted out of control of the business in 1932 by its board of directors and Sam Gumpertz was named vice president and general manager of the circus.[33]

Death

[edit]John Ringling died on December 2, 1936, in New York City. He was the last Ringling brother to die, as well as the longest-lived of the Ringling brothers. He was the only brother to reach his 70s.[34][36] Once one of the world's wealthiest men, he died with only $311 in the bank.[37] At his death, he willed his Sarasota mansion, the museum, and his entire art collection to the state of Florida. The house, Cà d'Zan, and the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art offer visitors a glimpse into the lifestyle of the Roaring 20s, a renowned art collection and library.[38] Another of John's legacies is the Ringling College of Art and Design, which asked to adopt his name because of the cultural influence of the museum and its collection. A museum devoted to the Ringling Brothers Circus has been established on the estate also.

After his death, the circus was operated by his nephew, John Ringling North, who sold the circus to Judge Roy Hofheinz of Houston and Washington, D.C., promoters Irvin Feld and Israel Feld in 1967.[39]

In 1991, John and Mable Ringling and his sister, Ida Ringling North, were exhumed from their original resting places and reburied at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, just in front and to the right of the Ca d'Zan. It is called the secret garden and John is buried between the two women.

The Ringling family

[edit]There were seven Ringling brothers and one sister (Ida), four of them (Alf, Al, Charles, and Otto) partnered with John to create the Ringling Bros. circus:[40][41][42][43]

- Albert Charles "Al" Ringling (1852–1916).

- Augustus Gustav "Gus" Ringling, Jr. (1854–1907); also listed as Charles August (Gus).[40][41]

- William Henry Otto "Otto" Ringling (1858–1911).[44]

- Alfred Theodore "Alf T." Ringling (1861–1919).

- Charles Edward "Charley" Ringling (1863–1926); also listed birth year 1864.[45]

- John Nicholas Ringling (1866–1936).

- Henry William George Ringling (1868–1918).[46]

- Ida Loraina Wilhelmina Ringling (1874–1950).[47]

References

[edit]- ^ "John Ringling Set the Tone for the Sarasota of Today". Sarasota Magazine.

- ^ John Ringling Florida Artists Hall of Fame

- ^ a b "John (1866-1936) and Mable (1875-1929) Ringling". Ringling Museum. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

John Ringling was born in McGregor, Iowa, on 31 May 1866, the sixth of seven surviving sons and daughter born to August and Marie Salomé Juliar. Five of the brothers joined together and started the Ringling Bros. Circus in 1884.

- ^ "Barnum and Bailey Circus history and Photos". www.circusesandsideshows.com.

- ^ "Adam Forepaugh and Sells Bros Circus". www.circusesandsideshows.com.

- ^ Joe McElroy. "How Did Foreign Relations in the US Change After the Revolutionary War? | The Classroom". Classroom.synonym.com. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "Ringling Bros. Circus routes 1916-18". Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Apps, Jerry (January 7, 2013). Ringlingville USA: The Stupendous Story of Seven Siblings and Their Stunning Circus Success. Wisconsin Historical Society. ISBN 9780870205491.

- ^ "Pages - RiBBB Circus Winter Quarters". Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "Biography of John Ringling". The Ringling.

- ^ To, Speeiaz (December 4, 1926). "Charles Ringling, Circus Owner, Dies. Member of World's Greatest Show Organization. One of Six Famous Brothers". New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

One of the famous "six brothers of Baraboo," Charles Ringling was the son of a harness maker of Baraboo, Wisconsin. The brothers, John, Charles, Otto, Al, ...

- ^ Ritacco, Joseph. Circus Atmosphere; John Ringling's castle on the cliffs, (201) magazine, January 2015. Accessed January 11, 2015.

- ^ Staff. "Gray Crag" Archived January 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Cliff Notes, May–June 2010, Palisades Interstate Park Commission. Accessed January 11, 2015. "It was in 1918 that John Ringling (that Ringing) and his wife Mable (née Burton) bought two big properties here and merged them into the hundred-acre estate they named Gray Crag."

- ^ "Circus Magnate, Art Patron, Showman, and Historian, John Ringling - Sarasota Florida". www.simplysarasota.com.

- ^ "Article 404 - Sarasota Herald-Tribune - Sarasota, FL". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ De Groft, Aaron H. "John Ringling 'In perpetua memoria': The Legacy and Prestige of Art and Collecting." Ph.D. dissertation—Florida State University, 2000. (Proquest Dissertations and Theses, accessed March 22, 2023)

- ^ "John Ringling's Art. How the collection developed". ringlingdocents.org.

- ^ "Man Who Started as a Clown Now Controls the Entire Big Top Industry". The New York Times. September 10, 1929. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

John Ringling, head of the Ringling Brothers-Barnum Bailey Combined Circus, has purchased the five circuses, with Winter quarters, of the American Circus Corporation, it was learned yesterday.

- ^ "Bailey and the Ringlings". Feld Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

In 1929, reacting to the fact that his competitor, the American Circus Corporation, had signed a contract to perform in New York's Madison Square Garden, Ringling purchased American Circus for $1.7-million. John had power and money. In one fell swoop, Ringling had absorbed five major shows: Sells-Floto, Al G. Barnes, Sparks, Hagenbeck-Wallace, and John Robinson.

- ^ "Business & Finance: Fallen Ringling". Time. November 27, 1933.

- ^ a b c d Ingham, John N., (1983). - Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders: A-G. - p.1177-1179. - ISBN 978-0-313-21362-5

- ^ a b c d e Herringshaw, Thomas William, (1922). - American Elite and Sociologist Bluebook. - American Blue Book Publishers. - p.418.

- ^ Klein, Henry H. (2003). - Dynastic America and Those Who Own It (1921). - p.107. - ISBN 978-0-7661-6729-2.

- ^ "EASTLAND COUNTY". - Handbook Of Texas. - Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ Goodsell, Charles M., Financial News Association (New York), and Henry E. Wallace, (1909). - The Manual of Statistics. - The Association. - p.169-170.

- ^ a b "RINGLING". - Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. - Oklahoma Historical Society.

—"WILSON". - Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. - Oklahoma Historical Society. - ^ a b Robinson, Gilbert L. - "TRANSPORTATION IN CARTER COUNTY, 1913-1917". - Chronicles of Oklahoma. - Volume 19, No. 4. - December, 1941. - Oklahoma Historical Society. - p.368-376.

- ^ Bryant, Keith L., (1974). - History of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. - New York, New York: Macmillan & Co. - p.254. - ISBN 978-0-02-517920-2.

- ^ a b Schwantes, Carlos A., (2003). - Going Places: Transportation Redefines the Twentieth-Century West. - Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. - p.129. - ISBN 978-0-253-34202-7.

—1918. - The Resources and Opportunities of Montana. - Montana Department of Agriculture and Publicity. - p.179. - ^ Snyder, S. A., (2005). - Scenic Driving Montana. - 2nd Edition. - Helena, Montana: Falcon Publishing. - p.152. - ISBN 978-0-7627-3030-8.

- ^ Cobb, Nathan. - "A Family Discovers Montana's Mystique". - Boston Globe. - May 14, 2000.

—French, Brett. - "A Sulfurous Soak". - Billings Gazette. - January 28, 2009.

—Duclaux, Denise. - "The Banker Who Never Comes in from the Cold". - ABA Banking Journal. - Vol. 89. - 1997. - ^ "Circus Owner Is Married by Mayor Hague in Jersey City. Met Bride in Europe". The New York Times. December 20, 1930. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

John Ringling, head of the Ringling Brothers-Barnum Bailey Combined Circus, and Mrs. Emily H. Buck of the Hotel Barclay were married yesterday afternoon ...

- ^ "Ringling takes old ally Sam Gumpertz into circus business". Chicago Tribune. November 6, 1932. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ a b "Circus in America TimeLine". Circus in America. Archived from the original on March 23, 2006. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

December 19, 1930. They were divorced July 6, 1936. John died December 2, 1936 in New York City and is buried ...

- ^ "Sued for Divorce". Time magazine. April 16, 1934. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

Mrs. Emily Haag Buck Ringling; by Circusman John Ringling; in Sarasota, Fla. Charges: vilification, physical violence which caused the pulse of Mr. Ringling, ill with thrombosis, on occasion to rise from 76 to 104.

- ^ "John Ringling dies of pneumonia at 70. Organizer of Great Circus Business Succumbs to Illness at Home Here. Last of the Brothers. Father's Harness Sale Started them on Career That Led to 'Greatest Show on Earth.'". The New York Times. December 2, 1936. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

John Ringling, who formed and directed one of the world's greatest ... He was 70 years old. With him when he died was his sister Hilda Ringling ...

- ^ Burnett, Gene M., (1986). - Florida's Past: People and Events That Shaped the State, Vol. 2. - Pineapple Press - p.190. - ISBN 978-1-56164-139-0.

- ^ Oliver, Mēgan. “Programming Special Collections: A Case Study of John Ringling’s Personal Art Library.” Art Documentation 35, no. 1 (2016): 164–71.

- ^ "Died". Time. June 17, 1985. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

John Ringling North, 81, flamboyant, fast-talking showman who from 1937 to '43 and from 1947 to '67 ran "The Greatest Show on Earth," the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, started by his five uncles in 1884; of a stroke; in Brussels. North took over the debt-spangled show after the death of his last uncle, John Ringling, and modernized it ...

- ^ a b "The Ringlings in the McGregor Area". Iowa Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

Beginning their tented circus in 1884, Alf T. Ringling, Al Ringling, Charles Ringling, John Ringling, and Otto Ringling soon became known as Kings Of The Circus World. A sixth brother, Henry Ringling, joined the show in 1886. In 1889 the seventh Ringling brother, A.G. "Gus" Ringling, joined the show ...

- ^ a b "Augustus Ringling Dead. Head of Tented Shows In America Dies in New Orleans" (PDF). The New York Times. August 19, 1907. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

When the Ringling Brothers bought the Barnum Bailey show they ... got a monopoly on the circus business in America. They now own outright three ...

- ^ Morris, Joan. - "The Seven Ringlins Were the Real Thing". - Contra Costa Times. - June 3, 2000.

- ^ Fox, Charles Philip, (1959). - A Ticket to the Circus: A Pictorial History of the Incredible Ringlings. - Seattle, Washington: Superior Publishing. - p.11. - 1252183.

- ^ "Tribute to the Memory of Otto Ringling. His Body Taken to Wisconsin" (PDF). New York Times. April 2, 1911. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ To, Speeiaz (December 4, 1926). "Charles Ringling, Circus Owner, Dies. Member of World's Greatest Show Organization. One of Six Famous Brothers". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

One of the famous "six brothers of Baraboo," Charles Ringling was the son of a harness maker of Baraboo, Wisconsin. The brothers, John, Charles, Otto, Al, ...

- ^ "Henry Ringling Dead" (PDF). New York Times. October 12, 1918. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

Henry Ringling, youngest of the six brothers who during the last 25-years have been prominent in the circus world died yesterday of heart and other internal disorders.

- ^ "Mrs. Ida Ringling North Dies in Sarasota". Washington Post. December 22, 1950. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2008.