Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Elephant

View on Wikipedia

| Elephants Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A female African bush elephant in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Superfamily: | Elephantoidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Living genera | |

|

For extinct genera, see Elephantidae | |

| |

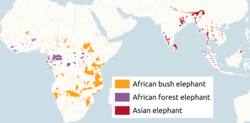

| Distribution of living elephant species | |

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), the African forest elephant (L. cyclotis), and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae and the order Proboscidea; extinct relatives include mammoths and mastodons. Distinctive features of elephants include a long proboscis called a trunk, tusks, large ear flaps, pillar-like legs, and tough but sensitive grey skin. The trunk is prehensile, bringing food and water to the mouth and grasping objects. Tusks, which are derived from the incisor teeth, serve both as weapons and as tools for moving objects and digging. The large ear flaps assist in maintaining a constant body temperature as well as in communication. African elephants have larger ears and concave backs, whereas Asian elephants have smaller ears and convex or level backs.

Elephants are scattered throughout sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia and are found in different habitats, including savannahs, forests, deserts, and marshes. They are herbivorous, and they stay near water when it is accessible. They are considered to be keystone species, due to their impact on their environments. Elephants have a fission–fusion society, in which multiple family groups come together to socialise. Females (cows) tend to live in family groups, which can consist of one female with her calves or several related females with offspring. The leader of a female group, usually the oldest cow, is known as the matriarch.

Males (bulls) leave their family groups when they reach puberty and may live alone or with other males. Adult bulls mostly interact with family groups when looking for a mate. They enter a state of increased testosterone and aggression known as musth, which helps them gain dominance over other males as well as reproductive success. Calves are the centre of attention in their family groups and rely on their mothers for as long as three years. Elephants can live up to 70 years in the wild. They communicate by touch, sight, smell, and sound; elephants use infrasound and seismic communication over long distances. Elephant intelligence has been compared with that of primates and cetaceans. They appear to have self-awareness, and possibly show concern for dying and dead individuals of their kind.

African bush elephants and Asian elephants are listed as endangered and African forest elephants as critically endangered on the IUCN Red Lists. One of the biggest threats to elephant populations is the ivory trade, as the animals are poached for their ivory tusks. Other threats to wild elephants include habitat destruction and conflicts with local people. Elephants are used as working animals in Asia. In the past, they were used in war; today, they are often controversially put on display in zoos, or employed for entertainment in circuses. Elephants have an iconic status in human culture and have been widely featured in art, folklore, religion, literature, and popular culture.

Etymology

[edit]The word elephant is derived from the Latin word elephas (genitive elephantis) 'elephant', which is the Latinised form of the ancient Greek ἐλέφας (elephas) (genitive ἐλέφαντος (elephantos,[1])) probably from a non-Indo-European language, likely Phoenician.[2] It is attested in Mycenaean Greek as e-re-pa (genitive e-re-pa-to) in Linear B syllabic script.[3][4] As in Mycenaean Greek, Homer used the Greek word to mean ivory, but after the time of Herodotus, it also referred to the animal.[1] The word elephant appears in Middle English as olyfaunt in c. 1300 and was borrowed from Old French oliphant in the 12th century.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]| A cladogram of the elephants within Afrotheria based on molecular evidence[5] |

Elephants belong to the family Elephantidae, the sole remaining family within the order Proboscidea. Their closest extant relatives are the sirenians (dugongs and manatees) and the hyraxes, with which they share the clade Paenungulata within the superorder Afrotheria.[6] Elephants and sirenians are further grouped in the clade Tethytheria.[7]

Three species of living elephants are recognised; the African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), and Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).[8] African elephants were traditionally considered a single species, Loxodonta africana, but molecular studies have affirmed their status as separate species.[9][10][11] Mammoths (Mammuthus) are nested within living elephants as they are more closely related to Asian elephants than to African elephants.[12] Another extinct genus of elephant, Palaeoloxodon, is also recognised, which appears to have close affinities with African elephants and to have hybridised with African forest elephants.[13] Palaeoloxodon was even larger than modern species, all exceeding 4 metres in height and 10 tonnes in body mass, with P. namadicus being a contender for the largest land mammal to have ever existed.[14]

Evolution

[edit]The earliest members of Proboscidea like Eritherium are known from the Paleocene of Africa, around 60 million years ago, the earliest proboscideans were much smaller than living elephants, with Eritherium having a body mass of around 3–8 kg (6.6–17.6 lb).[15] By the late Eocene, some members of Proboscidea like Barytherium had reached considerable size, with an estimated mass of around 2 tonnes,[14] while others like Moeritherium are suggested to have been semi-aquatic.[16]

| |||||||||

| Proboscidea phylogeny based on morphological and DNA evidence[17][18][13] |

A major event in proboscidean evolution was the collision of Afro-Arabia with Eurasia, during the Early Miocene, around 18–19 million years ago, allowing proboscideans to disperse from their African homeland across Eurasia and later, around 16–15 million years ago into North America across the Bering Land Bridge. Proboscidean groups prominent during the Miocene include the deinotheres, along with the more advanced elephantimorphs, including mammutids (mastodons), gomphotheres, amebelodontids (which includes the "shovel tuskers" like Platybelodon), choerolophodontids and stegodontids.[19] Around 10 million years ago, the earliest members of the family Elephantidae emerged in Africa, having originated from gomphotheres.[20]

Elephantids are distinguished from earlier proboscideans by a major shift in the molar morphology to parallel lophs rather than the cusps of earlier proboscideans, allowing them to become higher-crowned (hypsodont) and more efficient in consuming grass.[21] The Late Miocene saw major climactic changes, which resulted in the decline and extinction of many proboscidean groups.[19] The earliest members of the modern genera of elephants (Elephas, Loxodonta) as well as mammoths, appeared in Africa during the latest Miocene–early Pliocene around 7-4 million years ago.[22] The elephantid genera Elephas (which includes the living Asian elephant) and Mammuthus (mammoths) migrated out of Africa during the late Pliocene, around 3.6 to 3.2 million years ago.[23]

Over the course of the Early Pleistocene, all non-elephantid proboscidean genera outside of the Americas became extinct with the exception of Stegodon,[19] with gomphotheres dispersing into South America as part of the Great American interchange,[24] and mammoths migrating into North America around 1.5 million years ago.[25] At the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 800,000 years ago the elephantid genus Palaeoloxodon dispersed outside of Africa, becoming widely distributed in Eurasia.[26] Proboscideans were represented by around 23 species at the beginning of the Late Pleistocene. Proboscideans underwent a dramatic decline during the Late Pleistocene as part of the Late Pleistocene extinctions of most large mammals globally, with all remaining non-elephantid proboscideans (including Stegodon, mastodons, and the American gomphotheres Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon) and Palaeoloxodon becoming extinct, with mammoths only surviving in relict populations on islands around the Bering Strait into the Holocene, with their latest survival being on Wrangel Island, where they persisted until around 4,000 years ago.[19][27]

Over the course of their evolution, proboscideans grew in size. With that came longer limbs and wider feet with a more digitigrade stance, along with a larger head and shorter neck. The trunk evolved and grew longer to provide reach. The number of premolars, incisors, and canines decreased, and the cheek teeth (molars and premolars) became longer and more specialised. The incisors developed into tusks of different shapes and sizes.[28] Several species of proboscideans became isolated on islands and experienced insular dwarfism,[29] some dramatically reducing in body size, such as the 1 m (3 ft 3 in) tall dwarf elephant species Palaeoloxodon falconeri.[30]

Living species

[edit]| Name | Size | Appearance | Distribution | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana) | Male: 304–336 cm (10 ft 0 in – 11 ft 0 in) (shoulder height), 5.2–6.9 t (5.7–7.6 short tons) (weight); Female: 247–273 cm (8 ft 1 in – 8 ft 11 in) (shoulder height), 2.6–3.5 t (2.9–3.9 short tons) (weight).[14] | Relatively large and triangular ears, concave back, diamond shaped molar ridges, wrinkled skin, sloping abdomen, and two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk.[31] | Sub-Saharan Africa; forests, savannahs, deserts, wetlands, and near lakes.[32] |

|

| African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) | 209–231 cm (6 ft 10 in – 7 ft 7 in) (shoulder height), 1.7–2.3 t (1.9–2.5 short tons) (weight).[14] | Similar to the bush species, but with smaller and more rounded ears and thinner and straighter tusks.[31][32] | West and Central Africa; equatorial forests, but occasionally gallery forests and forest/grassland ecotones.[32] |

|

| Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) | Male: 261–289 cm (8 ft 7 in – 9 ft 6 in) (shoulder height), 3.5–4.6 t (3.9–5.1 short tons) (weight); Female: 228–252 cm (7 ft 6 in – 8 ft 3 in) (shoulder height), 2.3–3.1 t (2.5–3.4 short tons) (weight).[14] | Relatively small ears, convex or level back, dish-shaped forehead with two large bumps, narrow molar ridges, smooth skin with some blotches of depigmentation, a straightened or saggy abdomen, and one extension at the tip of the trunk.[31] | South and Southeast Asia; habitats with a mix of grasses, low woody plants, and trees, including dry thorn-scrub forests in southern India and Sri Lanka and evergreen forests in Malaya.[32][33] |

|

Anatomy

[edit]

Elephants are the largest living terrestrial animals. The skeleton is made up of 326–351 bones.[34] The vertebrae are connected by tight joints, which limit the backbone's flexibility. African elephants have 21 pairs of ribs, while Asian elephants have 19 or 20 pairs.[35] The skull contains air cavities (sinuses) that reduce the weight of the skull while maintaining overall strength. These cavities give the inside of the skull a honeycomb-like appearance. By contrast, the lower jaw is dense. The cranium is particularly large and provides enough room for the attachment of muscles to support the entire head.[34] The skull is built to withstand great stress, particularly when fighting or using the tusks. The brain is surrounded by arches in the skull, which serve as protection.[36] Because of the size of the head, the neck is relatively short to provide better support.[28] Elephants are homeotherms and maintain their average body temperature at ~ 36 °C (97 °F), with a minimum of 35.2 °C (95.4 °F) during the cool season, and a maximum of 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) during the hot dry season.[37]

Ears and eyes

[edit]

Elephant ear flaps, or pinnae, are 1–2 mm (0.039–0.079 in) thick in the middle with a thinner tip and supported by a thicker base. They contain numerous blood vessels called capillaries. Warm blood flows into the capillaries, releasing excess heat into the environment. This effect is increased by flapping the ears back and forth. Larger ear surfaces contain more capillaries, and more heat can be released. Of all the elephants, African bush elephants live in the hottest climates and have the largest ear flaps.[34][38] The ossicles are adapted for hearing low frequencies, being most sensitive at 1 kHz.[39]

Lacking a lacrimal apparatus (tear duct), the eye relies on the harderian gland in the orbit to keep it moist. A durable nictitating membrane shields the globe. The animal's field of vision is compromised by the location and limited mobility of the eyes.[40] Elephants are dichromats[41] and they can see well in dim light but not in bright light.[42]

Trunk

[edit]

The elongated and prehensile trunk, or proboscis, consists of both the nose and upper lip, which fuse in early fetal development.[28] This versatile appendage contains up to 150,000 separate muscle fascicles, with no bone and little fat. These paired muscles consist of two major types: superficial (surface) and internal. The former are divided into dorsal, ventral, and lateral muscles, while the latter are divided into transverse and radiating muscles. The muscles of the trunk connect to a bony opening in the skull. The nasal septum consists of small elastic muscles between the nostrils, which are divided by cartilage at the base.[43] A unique proboscis nerve – a combination of the maxillary and facial nerves – lines each side of the appendage.[44]

As a muscular hydrostat, the trunk moves through finely controlled muscle contractions, working both with and against each other.[44] Using three basic movements: bending, twisting, and longitudinal stretching or retracting, the trunk has near unlimited flexibility. Objects grasped by the end of the trunk can be moved to the mouth by curving the appendage inward. The trunk can also bend at different points by creating stiffened "pseudo-joints". The tip can be moved in a way similar to the human hand.[45] The skin is more elastic on the dorsal side of the elephant trunk than underneath; allowing the animal to stretch and coil while maintaining a strong grasp.[46] The flexibility of the trunk is aided by the numerous wrinkles in the skin.[47] The African elephants have two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk that allow them to pluck small food. The Asian elephant has only one and relies more on wrapping around a food item.[31] Asian elephant trunks have better motor coordination.[43]

The trunk's extreme flexibility allows it to forage and wrestle other elephants with it. It is powerful enough to lift up to 350 kg (770 lb), but it also has the precision to crack a peanut shell without breaking the seed. With its trunk, an elephant can reach items up to 7 m (23 ft) high and dig for water in the mud or sand below. It also uses it to clean itself.[48] Individuals may show lateral preference when grasping with their trunks: some prefer to twist them to the left, others to the right.[44] Elephant trunks are capable of powerful siphoning. They can expand their nostrils by 30%, leading to a 64% greater nasal volume, and can breathe in almost 30 times faster than a human sneeze, at over 150 m/s (490 ft/s).[49] They suck up water, which is squirted into the mouth or over the body.[28][49] The trunk of an adult Asian elephant is capable of retaining 8.5 L (2.2 US gal) of water.[43] They will also sprinkle dust or grass on themselves.[28] When underwater, the elephant uses its trunk as a snorkel.[50]

The trunk also acts as a sense organ. Its sense of smell may be four times greater than a bloodhound's nose.[51] The infraorbital nerve, which makes the trunk sensitive to touch, is thicker than both the optic and auditory nerves. Whiskers grow all along the trunk, and are particularly packed at the tip, where they contribute to its tactile sensitivity. Unlike those of many mammals, such as cats and rats, elephant whiskers do not move independently ("whisk") to sense the environment; the trunk itself must move to bring the whiskers into contact with nearby objects. Whiskers grow in rows along each side on the ventral surface of the trunk, which is thought to be essential in helping elephants balance objects there, whereas they are more evenly arranged on the dorsal surface. The number and patterns of whiskers are distinctly different between species.[52]

Damaging the trunk would be detrimental to an elephant's survival,[28] although in rare cases, individuals have survived with shortened ones. One trunkless elephant has been observed to graze using its lips with its hind legs in the air and balancing on its front knees.[43] Floppy trunk syndrome is a condition of trunk paralysis recorded in African bush elephants and involves the degeneration of the peripheral nerves and muscles. The disorder has been linked to lead poisoning.[53]

Teeth

[edit]Elephants usually have 26 teeth: the incisors, known as the tusks; 12 deciduous premolars; and 12 molars. Unlike most mammals, teeth are not replaced by new ones emerging from the jaws vertically. Instead, new teeth start at the back of the mouth and push out the old ones. The first chewing tooth on each side of the jaw falls out when the elephant is two to three years old. This is followed by four more tooth replacements at the ages of four to six, 9–15, 18–28, and finally in their early 40s. The final (usually sixth) set must last the elephant the rest of its life. Elephant teeth have loop-shaped dental ridges, which are more diamond-shaped in African elephants.[54]

Tusks

[edit]The tusks of an elephant are modified second incisors in the upper jaw. They replace deciduous milk teeth at 6–12 months of age and keep growing at about 17 cm (7 in) a year. As the tusk develops, it is topped with smooth, cone-shaped enamel that eventually wanes. The dentine is known as ivory and has a cross-section of intersecting lines, known as "engine turning", which create diamond-shaped patterns. Being living tissue, tusks are fairly soft and about as dense as the mineral calcite. The tusk protrudes from a socket in the skull, and most of it is external. At least one-third of the tusk contains the pulp, and some have nerves that stretch even further. Thus, it would be difficult to remove it without harming the animal. When removed, ivory will dry up and crack if not kept cool and wet. Tusks function in digging, debarking, marking, moving objects, and fighting.[55]

Elephants are usually right- or left-tusked, similar to humans, who are typically right- or left-handed. The dominant, or "master" tusk, is typically more worn down, as it is shorter and blunter. For African elephants, tusks are present in both males and females and are around the same length in both sexes, reaching up to 300 cm (9 ft 10 in),[55] but those of males tend to be more massive.[56] In the Asian species, only the males have large tusks. Female Asians have very small tusks, or none at all.[55] Tuskless males exist and are particularly common among Sri Lankan elephants.[57] Asian males can have tusks as long as Africans', but they are usually slimmer and lighter; the largest recorded was 302 cm (9 ft 11 in) long and weighed 39 kg (86 lb). Hunting for elephant ivory in Africa[58] and Asia[59] has resulted in an effective selection pressure for shorter tusks[60][61] and tusklessness.[62][63]

Skin

[edit]

An elephant's skin is generally very tough, at 2.5 cm (1 in) thick on the back and parts of the head. The skin around the mouth, anus, and inside of the ear is considerably thinner. Elephants are typically grey, but African elephants look brown or reddish after rolling in coloured mud. Asian elephants have some patches of depigmentation, particularly on the head. Calves have brownish or reddish hair, with the head and back being particularly hairy. As elephants mature, their hair darkens and becomes sparser, but dense concentrations of hair and bristles remain on the tip of the tail and parts of the head and genitals. Normally, the skin of an Asian elephant is covered with more hair than its African counterpart.[64] Their hair is thought to help them lose heat in their hot environments.[65]

Although tough, an elephant's skin is very sensitive and requires mud baths to maintain moisture and protection from burning and insect bites. After bathing, the elephant will usually use its trunk to blow dust onto its body, which dries into a protective crust. Elephants have difficulty releasing heat through the skin because of their low surface-area-to-volume ratio, which is many times smaller than that of a human. They have even been observed lifting up their legs to expose their soles to the air.[64] Elephants only have sweat glands between the toes,[66] but the skin allows water to disperse and evaporate, cooling the animal.[67][68] In addition, cracks in the skin may reduce dehydration and allow for increased thermal regulation in the long term.[69]

Legs, locomotion, and posture

[edit]To support the animal's weight, an elephant's limbs are positioned more vertically under the body than in most other mammals. The long bones of the limbs have cancellous bones in place of medullary cavities. This strengthens the bones while still allowing haematopoiesis (blood cell creation).[70] Both the front and hind limbs can support an elephant's weight, although 60% is borne by the front.[71] The position of the limbs and leg bones allows an elephant to stand still for extended periods of time without tiring. Elephants are incapable of turning their manus because the ulna and radius of the front legs are secured in pronation.[70] Elephants may also lack the pronator quadratus and pronator teres muscles or have very small ones.[72] The circular feet of an elephant have soft tissues, or "cushion pads" beneath the manus or pes, which allow them to bear the animal's great mass.[71] They appear to have a sesamoid, an extra "toe" similar in placement to a giant panda's extra "thumb", that also helps in weight distribution.[73] As many as five toenails can be found on both the front and hind feet.[31]

Elephants can move both forward and backward, but are incapable of trotting, jumping, or galloping. They can move on land only by walking or ambling: a faster gait similar to running.[70][74] In walking, the legs act as pendulums, with the hips and shoulders moving up and down while the foot is planted on the ground. The fast gait does not meet all the criteria of running, since there is no point where all the feet are off the ground, although the elephant uses its legs much like other running animals, and can move faster by quickening its stride. Fast-moving elephants appear to 'run' with their front legs, but 'walk' with their hind legs and can reach a top speed of 25 km/h (16 mph). At this speed, most other quadrupeds are well into a gallop, even accounting for leg length. Spring-like kinetics could explain the difference between the motion of elephants and other animals.[74][75] The cushion pads expand and contract, and reduce both the pain and noise that would come from a very heavy animal moving.[71] Elephants are capable swimmers: they can swim for up to six hours while completely waterborne, moving at 2.1 km/h (1 mph) and traversing up to 48 km (30 mi) continuously.[76]

Internal systems

[edit]The brain of an elephant weighs 4.5–5.5 kg (10–12 lb) compared to 1.6 kg (4 lb) for a human brain.[77] It is the largest of all terrestrial mammals.[78] While the elephant brain is larger overall, it is proportionally smaller than the human brain. At birth, an elephant's brain already weighs 30–40% of its adult weight. The cerebrum and cerebellum are well developed, and the temporal lobes are so large that they bulge out laterally.[77] Their temporal lobes are proportionally larger than those of other animals, including humans.[78] The throat of an elephant appears to contain a pouch where it can store water for later use.[28] The larynx of the elephant is the largest known among mammals. The vocal folds are anchored close to the epiglottis base. When comparing an elephant's vocal folds to those of a human, an elephant's are proportionally longer, thicker, with a greater cross-sectional area. In addition, they are located further up the vocal tract with an acute slope.[79]

The heart of an elephant weighs 12–21 kg (26–46 lb). Its apex has two pointed ends, an unusual trait among mammals.[77] In addition, the ventricles of the heart split towards the top, a trait also found in sirenians.[80] When upright, the elephant's heart beats around 28 beats per minute and actually speeds up to 35 beats when it lies down.[77] The blood vessels are thick and wide and can hold up under high blood pressure.[80] The lungs are attached to the diaphragm, and breathing relies less on the expanding of the ribcage.[77] Connective tissue exists in place of the pleural cavity. This may allow the animal to deal with the pressure differences when its body is underwater and its trunk is breaking the surface for air.[50] Elephants breathe mostly with the trunk but also with the mouth. They have a hindgut fermentation system, and their large and small intestines together reach 35 m (115 ft) in length. Less than half of an elephant's food intake gets digested, despite the process lasting a day.[77] An elephant's bladder can store up to 18 litres of urine[81] and its kidneys can produce more than 50 litres of urine per day.[82]

Sex characteristics

[edit]A male elephant's testes, like other Afrotheria,[83] are internally located near the kidneys.[84] The penis can be as long as 100 cm (39 in) with a 16 cm (6 in) wide base. It curves to an 'S' when fully erect and has an orifice shaped like a Y. The female's clitoris may be 40 cm (16 in). The vulva is found lower than in other herbivores, between the hind legs instead of under the tail. Determining pregnancy status can be difficult due to the animal's large belly. The female's mammary glands occupy the space between the front legs, which puts the suckling calf within reach of the female's trunk.[77] Elephants have a unique organ, the temporal gland, located on both sides of the head. This organ is associated with sexual behaviour, and males secrete a fluid from it when in musth.[85] Females have also been observed with these secretions.[51]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Elephants are herbivorous and will eat leaves, twigs, fruit, bark, grass, and roots. African elephants mostly browse, while Asian elephants mainly graze.[32] They can eat as much as 300 kg (660 lb) of food and drink 40 L (11 US gal) of water in a day. Elephants tend to stay near water sources.[32][86] They have morning, afternoon, and nighttime feeding sessions. At midday, elephants rest under trees and may doze off while standing. Sleeping occurs at night while the animal is lying down.[86] Elephants average 3–4 hours of sleep per day.[87] Both males and family groups typically move no more than 20 km (12 mi) a day, but distances as far as 180 km (112 mi) have been recorded in the Etosha region of Namibia.[88] Elephants go on seasonal migrations in response to changes in environmental conditions.[89] In northern Botswana, they travel 325 km (202 mi) to the Chobe River after the local waterholes dry up in late August.[90]

Because of their large size, elephants have a huge impact on their environments and are considered keystone species. Their habit of uprooting trees and undergrowth can transform savannah into grasslands;[91] smaller herbivores can access trees mowed down by elephants.[86] When they dig for water during droughts, they create waterholes that can be used by other animals. When they use waterholes, they end up making them bigger.[91] At Mount Elgon, elephants dig through caves and pave the way for ungulates, hyraxes, bats, birds, and insects.[91] Elephants are important seed dispersers; African forest elephants consume and deposit many seeds over great distances, with either no effect or a positive effect on germination.[92] In Asian forests, large seeds require giant herbivores like elephants and rhinoceros for transport and dispersal. This ecological niche cannot be filled by the smaller Malayan tapir.[93] Because most of the food elephants eat goes undigested, their dung can provide food for other animals, such as dung beetles and monkeys.[91] Elephants can have a negative impact on ecosystems. At Murchison Falls National Park in Uganda, elephant numbers have threatened several species of small birds that depend on woodlands. Their weight causes the soil to compress, leading to runoff and erosion.[86]

Elephants typically coexist peacefully with other herbivores, which will usually stay out of their way. Some aggressive interactions between elephants and rhinoceros have been recorded.[86] The size of adult elephants makes them nearly invulnerable to predators.[33] Calves may be preyed on by lions, spotted hyenas, and wild dogs in Africa[94] and tigers in Asia.[33] The lions of Savuti, Botswana, have adapted to hunting elephants, targeting calves, juveniles or even sub-adults.[95][96] There are rare reports of adult Asian elephants falling prey to tigers.[97] Elephants tend to have high numbers of parasites, particularly nematodes, compared to many other mammals. This may be due to elephants being less vulnerable to predation; in other mammal species, individuals weakened by significant parasite loads are easily killed off by predators, removing them from the population.[98]

Social organisation

[edit]

Elephants are generally gregarious animals. African bush elephants in particular have a complex, stratified social structure.[99] Female elephants spend their entire lives in tight-knit matrilineal family groups.[100] They are led by the matriarch, who is often the eldest female.[101] She remains leader of the group until death[94] or if she no longer has the energy for the role;[102] a study on zoo elephants found that the death of the matriarch led to greater stress in the surviving elephants.[103] When her tenure is over, the matriarch's eldest daughter takes her place instead of her sister (if present).[94] One study found that younger matriarchs take potential threats less seriously.[104] Large family groups may split if they cannot be supported by local resources.[105]

At Amboseli National Park, Kenya, female groups may consist of around ten members, including four adults and their dependent offspring. Here, a cow's life involves interaction with those outside her group. Two separate families may associate and bond with each other, forming what are known as bond groups. During the dry season, elephant families may aggregate into clans. These may number around nine groups, in which clans do not form strong bonds but defend their dry-season ranges against other clans. The Amboseli elephant population is further divided into the "central" and "peripheral" subpopulations.[100]

Female Asian elephants tend to have more fluid social associations.[99] In Sri Lanka, there appear to be stable family units or "herds" and larger, looser "groups". They have been observed to have "nursing units" and "juvenile-care units". In southern India, elephant populations may contain family groups, bond groups, and possibly clans. Family groups tend to be small, with only one or two adult females and their offspring. A group containing more than two cows and their offspring is known as a "joint family". Malay elephant populations have even smaller family units and do not reach levels above a bond group. Groups of African forest elephants typically consist of one cow with one to three offspring. These groups appear to interact with each other, especially at forest clearings.[100]

Adult males live separate lives. As he matures, a bull associates more with outside males or even other families. At Amboseli, young males may be away from their families 80% of the time by 14–15 years of age. When males permanently leave, they either live alone or with other males. The former is typical of bulls in dense forests. A dominance hierarchy exists among males, whether they are social or solitary. Dominance depends on age, size, and sexual condition.[106] Male elephants can be quite sociable when not competing for mates and form vast and fluid social networks.[107][108] Older bulls act as the leaders of these groups.[109] The presence of older males appears to subdue the aggression and "deviant" behaviour of younger ones.[110] The largest all-male groups can reach close to 150 individuals. Adult males and females come together to breed. Bulls will accompany family groups if a cow is in oestrous.[106]

Sexual behaviour

[edit]Musth

[edit]

Adult males enter a state of increased testosterone known as musth. In a population in southern India, males first enter musth at 15 years old, but it is not very intense until they are older than 25. At Amboseli, no bulls under 24 were found to be in musth, while half of those aged 25–35 and all those over 35 were. In some areas, there may be seasonal influences on the timing of musths. The main characteristic of a bull's musth is a fluid discharged from the temporal gland that runs down the side of his face. Behaviours associated with musth include walking with a high and swinging head, nonsynchronous ear flapping, picking at the ground with the tusks, marking, rumbling, and urinating in the sheath. The length of this varies between males of different ages and conditions, lasting from days to months.[111]

Males become extremely aggressive during musth. Size is the determining factor in agonistic encounters when the individuals have the same condition. In contests between musth and non-musth individuals, musth bulls win the majority of the time, even when the non-musth bull is larger. A male may stop showing signs of musth when he encounters a musth male of higher rank. Those of equal rank tend to avoid each other. Agonistic encounters typically consist of threat displays, chases, and minor sparring. Rarely do they full-on fight.[111]

There is at least one documented case of infanticide among Asian elephants at Dong Yai Wildlife Sanctuary, with the researchers describing it as most likely normal behaviour among aggressive musth elephants.[112]

Mating

[edit]

Elephants are polygynous breeders,[113] and most copulations occur during rainfall.[114] An oestrous cow uses pheromones in her urine and vaginal secretions to signal her readiness to mate. A bull will follow a potential mate and assess her condition with the flehmen response, which requires him to collect a chemical sample with his trunk and taste it with the vomeronasal organ at the roof of the mouth.[115] The oestrous cycle of a cow lasts 14–16 weeks, with the follicular phase lasting 4–6 weeks and the luteal phase lasting 8–10 weeks. While most mammals have one surge of luteinizing hormone during the follicular phase, elephants have two. The first (or anovulatory) surge, appears to change the female's scent, signaling to males that she is in heat, but ovulation does not occur until the second (or ovulatory) surge.[116] Cows over 45–50 years of age are less fertile.[102]

Bulls engage in a behaviour known as mate-guarding, where they follow oestrous females and defend them from other males.[117] Most mate-guarding is done by musth males, and females seek them out, particularly older ones.[118] Musth appears to signal to females the condition of the male, as weak or injured males do not have normal musths.[119] For young females, the approach of an older bull can be intimidating, so her relatives stay nearby for comfort.[120] During copulation, the male rests his trunk on the female.[121] The penis is mobile enough to move without the pelvis.[82] Before mounting, it curves forward and upward. Copulation lasts about 45 seconds and does not involve pelvic thrusting or an ejaculatory pause.[122]

Homosexual behaviour has been observed in both sexes. As in heterosexual interactions, this involves mounting. Male elephants sometimes stimulate each other by playfighting, and "championships" may form between old bulls and younger males. Female same-sex behaviours have been documented only in captivity, where they engage in mutual masturbation with their trunks.[123]

Birth and development

[edit]Gestation in elephants typically lasts between one and a half and two years and the female will not give birth again for at least four years.[124] The relatively long pregnancy is supported by several corpora lutea and gives the foetus more time to develop, particularly the brain and trunk.[125] Births tend to take place during the wet season.[114] Typically, only a single young is born, but twins sometimes occur.[125] Calves are born roughly 85 cm (33 in) tall and with a weight of around 120 kg (260 lb).[120] They are precocial and quickly stand and walk to follow their mother and family herd.[126] A newborn calf will attract the attention of all the herd members. Adults and most of the other young will gather around the newborn, touching and caressing it with their trunks. For the first few days, the mother limits access to her young. Alloparenting – where a calf is cared for by someone other than its mother – takes place in some family groups. Allomothers are typically aged two to twelve years.[120]

For the first few days, the newborn is unsteady on its feet and needs its mother's help. It relies on touch, smell, and hearing, as its eyesight is less developed. With little coordination in its trunk, it can only flop it around which may cause it to trip. When it reaches its second week, the calf can walk with more balance and has more control over its trunk. After its first month, the trunk can grab and hold objects but still lacks sucking abilities, and the calf must bend down to drink. It continues to stay near its mother as it is still reliant on her. For its first three months, a calf relies entirely on its mother's milk, after which it begins to forage for vegetation and can use its trunk to collect water. At the same time, there is progress in lip and leg movements. By nine months, mouth, trunk, and foot coordination are mastered. Suckling bouts tend to last 2–4 min/hr for a calf younger than a year. After a year, a calf is fully capable of grooming, drinking, and feeding itself. It still needs its mother's milk and protection until it is at least two years old. Suckling after two years may improve growth, health, and fertility.[126]

Play behaviour in calves differs between the sexes; females run or chase each other while males play-fight. The former are sexually mature by the age of nine years[120] while the latter become mature around 14–15 years.[106] Adulthood starts at about 18 years of age in both sexes.[127][128] Elephants have long lifespans, reaching 60–70 years of age.[54] Lin Wang, a captive male Asian elephant, lived for 86 years.[129]

Communication

[edit]Elephants communicate in various ways. Individuals greet one another by touching each other on the mouth, temporal glands, and genitals. This allows them to pick up chemical cues. Older elephants use trunk-slaps, kicks, and shoves to control younger ones. Touching is especially important for mother–calf communication. When moving, elephant mothers will touch their calves with their trunks or feet when side-by-side or with their tails if the calf is behind them. A calf will press against its mother's front legs to signal it wants to rest and will touch her breast or leg when it wants to suckle.[130]

Visual displays mostly occur in agonistic situations. Elephants will try to appear more threatening by raising their heads and spreading their ears. They may add to the display by shaking their heads and snapping their ears, as well as tossing around dust and vegetation. They are usually bluffing when performing these actions. Excited elephants also raise their heads and spread their ears but additionally may raise their trunks. Submissive elephants will lower their heads and trunks, as well as flatten their ears against their necks, while those that are ready to fight will bend their ears in a V shape.[131]

Elephants produce several vocalisations—some of which pass through the trunk[132]—for both short and long range communication. This includes trumpeting, bellowing, roaring, growling, barking, snorting, and rumbling.[132][133] Elephants can produce infrasonic rumbles.[134] For Asian elephants, these calls have a frequency of 14–24 Hz, with sound pressure levels of 85–90 dB and last 10–15 seconds.[135] For African elephants, calls range from 15 to 35 Hz with sound pressure levels as high as 117 dB, allowing communication for many kilometres, possibly over 10 km (6 mi).[136] Elephants are known to communicate with seismics, vibrations produced by impacts on the earth's surface or acoustical waves that travel through it. An individual foot stomping or mock charging can create seismic signals that can be heard at travel distances of up to 32 km (20 mi). Seismic waveforms produced by rumbles travel 16 km (10 mi).[137][138]

Intelligence and cognition

[edit]Elephants are among the most intelligent animals. They exhibit mirror self-recognition, an indication of self-awareness and cognition that has also been demonstrated in some apes and dolphins.[139] One study of a captive female Asian elephant suggested the animal was capable of learning and distinguishing between several visual and some acoustic discrimination pairs. This individual was even able to score a high accuracy rating when re-tested with the same visual pairs a year later.[140] Elephants are among the species known to use tools. An Asian elephant has been observed fine-tuning branches for use as flyswatters.[141] Tool modification by these animals is not as advanced as that of chimpanzees. Elephants are popularly thought of as having an excellent memory. This could have a factual basis; they possibly have cognitive maps which give them long lasting memories of their environment on a wide scale. Individuals may be able to remember where their family members are located.[42]

Scientists debate the extent to which elephants feel emotion. They are attracted to the bones of their own kind, regardless of whether they are related.[142] As with chimpanzees and dolphins, a dying or dead elephant may elicit attention and aid from others, including those from other groups. This has been interpreted as expressing "concern";[143] however, the Oxford Companion to Animal Behaviour (1987) said that "one is well advised to study the behaviour rather than attempting to get at any underlying emotion".[144]

Conservation

[edit]Status

[edit]

African bush elephants were listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2021,[145] and African forest elephants were listed as Critically Endangered in the same year.[146] In 1979, Africa had an estimated population of at least 1.3 million elephants, possibly as high as 3.0 million. A decade later, the population was estimated to be 609,000; with 277,000 in Central Africa, 110,000 in Eastern Africa, 204,000 in Southern Africa, and 19,000 in Western Africa. The population of rainforest elephants was lower than anticipated, at around 214,000 individuals. Between 1977 and 1989, elephant populations declined by 74% in East Africa. After 1987, losses in elephant numbers hastened, and savannah populations from Cameroon to Somalia experienced a decline of 80%. African forest elephants had a total loss of 43%. Population trends in southern Africa were various, with unconfirmed losses in Zambia, Mozambique and Angola while populations grew in Botswana and Zimbabwe and were stable in South Africa.[147] The IUCN estimated that total population in Africa is estimated at to 415,000 individuals for both species combined as of 2016.[148]

African elephants receive at least some legal protection in every country where they are found. Successful conservation efforts in certain areas have led to high population densities while failures have led to declines as high as 70% or more of the course of ten years. As of 2008, local numbers were controlled by contraception or translocation. Large-scale cullings stopped in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1989, the African elephant was listed under Appendix I by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), making trade illegal. Appendix II status (which allows restricted trade) was given to elephants in Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe in 1997 and South Africa in 2000. In some countries, sport hunting of the animals is legal; Botswana, Cameroon, Gabon, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have CITES export quotas for elephant trophies.[145]

In 2020, the IUCN listed the Asian elephant as endangered due to the population declining by half over "the last three generations".[149] Asian elephants once ranged from Western to East Asia and south to Sumatra.[150] and Java. It is now extinct in these areas,[149] and the current range of Asian elephants is highly fragmented.[150] The total population of Asian elephants is estimated to be around 40,000–50,000, although this may be a loose estimate. Around 60% of the population is in India. Although Asian elephants are declining in numbers overall, particularly in Southeast Asia, the population in the Western Ghats may have stabilised.[149]

Threats

[edit]

The poaching of elephants for their ivory, meat and hides has been one of the major threats to their existence.[149] Historically, numerous cultures made ornaments and other works of art from elephant ivory, and its use was comparable to that of gold.[151] The ivory trade contributed to the fall of the African elephant population in the late 20th century.[145] This prompted international bans on ivory imports, starting with the United States in June 1989, and followed by bans in other North American countries, western European countries, and Japan.[151] Around the same time, Kenya destroyed all its ivory stocks.[152] Ivory was banned internationally by CITES in 1990. Following the bans, unemployment rose in India and China, where the ivory industry was important economically. By contrast, Japan and Hong Kong, which were also part of the industry, were able to adapt and were not as badly affected.[151] Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Malawi wanted to continue the ivory trade and were allowed to, since their local populations were healthy, but only if their supplies were from culled individuals or those that died of natural causes.[152]

The ban allowed the elephant to recover in parts of Africa.[151] In February 2012, 650 elephants in Bouba Njida National Park, Cameroon, were slaughtered by Chadian raiders.[153] This has been called "one of the worst concentrated killings" since the ivory ban.[152] Asian elephants are potentially less vulnerable to the ivory trade, as females usually lack tusks. Still, members of the species have been killed for their ivory in some areas, such as Periyar National Park in India.[149] China was the biggest market for poached ivory but announced they would phase out the legal domestic manufacture and sale of ivory products in May 2015, and in September 2015, China and the United States said "they would enact a nearly complete ban on the import and export of ivory" due to causes of extinction.[154]

Other threats to elephants include habitat destruction and fragmentation. The Asian elephant lives in areas with some of the highest human populations and may be confined to small islands of forest among human-dominated landscapes. Elephants commonly trample and consume crops, which contributes to conflicts with humans, and both elephants and humans have died by the hundreds as a result. Mitigating these conflicts is important for conservation. One proposed solution is the protection of wildlife corridors which give populations greater interconnectivity and space.[149] Chili pepper products as well as guarding with defense tools have been found to be effective in preventing crop-raiding by elephants. Less effective tactics include beehive and electric fences.[155]

Human relations

[edit]Working animal

[edit]

Elephants have been working animals since at least the Indus Valley civilization over 4,000 years ago[156] and continue to be used in modern times. There were 13,000–16,500 working elephants employed in Asia in 2000. These animals are typically captured from the wild when they are 10–20 years old, the age range when they are both more trainable and can work for more years.[157] They were traditionally captured with traps and lassos, but since 1950, tranquillisers have been used.[158] Individuals of the Asian species have often been trained as working animals. Asian elephants are used to carry and pull both objects and people in and out of areas as well as lead people in religious celebrations. They are valued over mechanised tools as they can perform the same tasks but in more difficult terrain, with strength, memory, and delicacy. Elephants can learn over 30 commands.[157] Musth bulls are difficult and dangerous to work with and so are chained up until their condition passes.[159]

In India, many working elephants are alleged to have been subject to abuse. They and other captive elephants are thus protected under The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960.[160] In both Myanmar and Thailand, deforestation and other economic factors have resulted in sizable populations of unemployed elephants resulting in health problems for the elephants themselves as well as economic and safety problems for the people amongst whom they live.[161][162]

The practice of working elephants has also been attempted in Africa. The taming of African elephants in the Belgian Congo began by decree of Leopold II of Belgium during the 19th century and continues to the present with the Api Elephant Domestication Centre.[163]

Warfare

[edit]

Historically, elephants were considered formidable instruments of war. They were described in Sanskrit texts as far back as 1500 BC. From South Asia, the use of elephants in warfare spread west to Persia[164] and east to Southeast Asia.[165] The Persians used them during the Achaemenid Empire (between the 6th and 4th centuries BC)[164] while Southeast Asian states first used war elephants possibly as early as the 5th century BC and continued to the 20th century.[165] War elephants were also employed in the Mediterranean and North Africa throughout the classical period since the reign of Ptolemy II in Egypt. The Carthaginian general Hannibal famously took African elephants across the Alps during his war with the Romans and reached the Po Valley in 218 BC with all of them alive, but died of disease and combat a year later.[164]

An elephant's head and sides were equipped with armour, the trunk may have had a sword tied to it and tusks were sometimes covered with sharpened iron or brass. Trained elephants would attack both humans and horses with their tusks. They might have grasped an enemy soldier with the trunk and tossed him to their mahout, or pinned the soldier to the ground and speared him. Some shortcomings of war elephants included their great visibility, which made them easy to target, and limited maneuverability compared to horses. Alexander the Great achieved victory over armies with war elephants by having his soldiers injure the trunks and legs of the animals which caused them to panic and become uncontrollable.[164]

Zoos and circuses

[edit]

Elephants have traditionally been a major part of zoos and circuses around the world. In circuses, they are trained to perform tricks. The most famous circus elephant was probably Jumbo (1861 – 15 September 1885), who was a major attraction in the Barnum & Bailey Circus.[166][167] These animals do not reproduce well in captivity due to the difficulty of handling musth bulls and limited understanding of female oestrous cycles. Asian elephants were always more common than their African counterparts in modern zoos and circuses. After CITES listed the Asian elephant under Appendix I in 1975, imports of the species almost stopped by the end of the 1980s. Subsequently, the US received many captive African elephants from Zimbabwe, which had an overabundance of the animals.[167]

Keeping elephants in zoos has met with some controversy. Proponents of zoos argue that they allow easy access to the animals and provide fund and knowledge for preserving their natural habitats, as well as safekeeping for the species. Opponents claim that animals in zoos are under physical and mental stress.[168] Elephants have been recorded displaying stereotypical behaviours in the form of wobbling the body or head and pacing the same route both forwards and backwards. This has been observed in 54% of individuals in UK zoos.[169] One study claims wild elephants in protected areas of Africa and Asia live more than twice as long as those in European zoos; the median lifespan of elephants in European zoos being 17 years. Other studies suggest that elephants in zoos live a similar lifespan as those in the wild.[170]

The use of elephants in circuses has also been controversial; the Humane Society of the United States has accused circuses of mistreating and distressing their animals.[171] In testimony to a US federal court in 2009, Barnum & Bailey Circus CEO Kenneth Feld acknowledged that circus elephants are struck behind their ears, under their chins, and on their legs with metal-tipped prods, called bull hooks or ankus. Feld stated that these practices are necessary to protect circus workers and acknowledged that an elephant trainer was rebuked for using an electric prod on an elephant. Despite this, he denied that any of these practices hurt the animals.[172] Some trainers have tried to train elephants without the use of physical punishment. Ralph Helfer is known to have relied on positive reinforcement when training his animals.[173] Barnum and Bailey circus retired its touring elephants in May 2016.[174]

Attacks

[edit]Elephants can exhibit bouts of aggressive behaviour and engage in destructive actions against humans.[175] In Africa, groups of adolescent elephants damaged homes in villages after cullings in the 1970s and 1980s. Because of the timing, these attacks have been interpreted as vindictive.[176][177] In parts of India, male elephants have entered villages at night, destroying homes and killing people. From 2000 to 2004, 300 people died in Jharkhand, and in Assam, 239 people were reportedly killed between 2001 and 2006.[175] Throughout the country, 1,500 people were killed by elephants between 2019 and 2022, which led to 300 elephants being killed in kind.[178] Local people have reported that some elephants were drunk during the attacks, though officials have disputed this.[179][180] Purportedly drunk elephants attacked an Indian village in December 2002, killing six people, which led to the retaliatory slaughter of about 200 elephants by locals.[181]

Cultural significance

[edit]Elephants have a universal presence in global culture. They have been represented in art since Paleolithic times. Africa, in particular, contains many examples of elephant rock art, especially in the Sahara and southern Africa.[182] In Asia, the animals are depicted as motifs in Hindu and Buddhist shrines and temples.[183] Elephants were often difficult to portray by people with no first-hand experience of them.[184] The ancient Romans, who kept the animals in captivity, depicted elephants more accurately than medieval Europeans who portrayed them more like fantasy creatures, with horse, bovine, and boar-like traits, and trumpet-like trunks. As Europeans gained more access to captive elephants during the 15th century, depictions of them became more accurate, including one made by Leonardo da Vinci.[185]

Elephants have been the subject of religious beliefs. The Mbuti people of central Africa believe that the souls of their dead ancestors resided in elephants.[183] Similar ideas existed among other African societies, who believed that their chiefs would be reincarnated as elephants. During the 10th century AD, the people of Igbo-Ukwu, in modern-day Nigeria, placed elephant tusks underneath their dead leader's feet in the grave.[186] The animals' importance is only totemic in Africa but is much more significant in Asia.[187] In Sumatra, elephants have been associated with lightning. Likewise, in Hinduism, they are linked with thunderstorms as Airavata, the father of all elephants, represents both lightning and rainbows.[183] One of the most important Hindu deities, the elephant-headed Ganesha, is ranked equal with the supreme gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Brahma in some traditions.[188] Ganesha is associated with writers and merchants, and it is believed that he can give people success as well as grant them their desires, but could also take these things away.[183] In Buddhism, Buddha is said to have taken the form of a white elephant when he entered his mother's womb to be reincarnated as a human.[189]

In Western popular culture, elephants symbolise the exotic, especially since – as with the giraffe, hippopotamus, and rhinoceros – there are no similar animals familiar to Western audiences. As characters, elephants are most common in children's stories, where they are portrayed positively. They are typically surrogates for humans with ideal human values. Many stories tell of isolated young elephants returning to or finding a family, such as "The Elephant's Child" from Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories, Disney's Dumbo, and Kathryn and Byron Jackson's The Saggy Baggy Elephant. Other elephant heroes given human qualities include Jean de Brunhoff's Babar, David McKee's Elmer, and Dr. Seuss's Horton.[190]

Several cultural references emphasise the elephant's size and strangeness. For instance, a "white elephant" is a byword for something that is weird, unwanted, and has no value.[190] The expression "elephant in the room" refers to something that is being ignored but ultimately must be addressed.[191] The story of the blind men and an elephant involves blind men touching different parts of an elephant and trying to figure out what it is.[192]

See also

[edit]- Animal track

- Desert elephant

- Elephants' graveyard

- List of individual elephants

- Motty, captive hybrid of an Asian and African elephant

- National Elephant Day (Thailand)

- World Elephant Day

References

[edit]- ^ a b Liddell, H. G.; Scott, R (1940). "ἐλέφας". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b Harper, D. "Elephant". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Lujan, E. R.; Bernabe, A. (2012). "Ivory and horn production in Mycenaean texts". In Nosch, M.-L.; Laffineur, R. (eds.). Kosmos. Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegaeum 33. Liège: Peeters. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "elephant". Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ Tabuce, R.; Asher, R. J.; Lehmann, T. (2008). "Afrotherian mammals: a review of current data" (PDF). Mammalia. 72: 2–14. doi:10.1515/MAMM.2008.004. ISSN 0025-1461. S2CID 46133294. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Kellogg, M.; Burkett, S.; Dennis, T. R.; Stone, G.; Gray, B. A.; McGuire, P. M.; Zori, R. T.; Stanyon, R. (2007). "Chromosome painting in the manatee supports Afrotheria and Paenungulata". Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 6. Bibcode:2007BMCEE...7....6K. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-6. PMC 1784077. PMID 17244368.

- ^ Ozawa, T.; Hayashi, S.; Mikhelson, V. M. (1997). "Phylogenetic position of mammoth and Steller's sea cow within tethytheria demonstrated by mitochondrial DNA sequences". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 44 (4): 406–13. Bibcode:1997JMolE..44..406O. doi:10.1007/PL00006160. PMID 9089080. S2CID 417046.

- ^ Shoshani, J. (2005). "Order Proboscidea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. Archived from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ Rohland, N.; Reich, D.; Mallick, S.; Meyer, M.; Green, R. E.; Georgiadis, N. J.; Roca, A. L.; Hofreiter, M. (2010). Penny, David (ed.). "Genomic DNA Sequences from Mastodon and Woolly Mammoth Reveal Deep Speciation of Forest and Savanna Elephants". PLOS Biology. 8 (12) e1000564. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564. PMC 3006346. PMID 21203580.

- ^ Ishida, Y.; Oleksyk, T. K.; Georgiadis, N. J.; David, V. A.; Zhao, K.; Stephens, R. M.; Kolokotronis, S.-O.; Roca, A. L. (2011). Murphy, William J (ed.). "Reconciling apparent conflicts between mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies in African elephants". PLOS ONE. 6 (6) e20642. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620642I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020642. PMC 3110795. PMID 21701575.

- ^ Roca, Alfred L.; Ishida, Yasuko; Brandt, Adam L.; Benjamin, Neal R.; Zhao, Kai; Georgiadis, Nicholas J. (2015). "Elephant Natural History: A Genomic Perspective". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 3 (1): 139–167. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110838. PMID 25493538.

- ^ Roca, Alfred L.; Ishida, Yasuko; Brandt, Adam L.; Benjamin, Neal R.; Zhao, Kai; Georgiadis, Nicholas J. (2015). "Elephant Natural History: A Genomic Perspective". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 3 (1): 139–167. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110838. PMID 25493538.

- ^ a b Palkopoulou, Eleftheria; Lipson, Mark; Mallick, Swapan; Nielsen, Svend; Rohland, Nadin; Baleka, Sina; Karpinski, Emil; Ivancevic, Atma M.; To, Thu-Hien; Kortschak, R. Daniel; Raison, Joy M. (13 March 2018). "A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (11): E2566 – E2574. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E2566P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720554115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5856550. PMID 29483247.

- ^ a b c d e Larramendi, A. (2015). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- ^ Gheerbrant, E. (2009). "Paleocene emergence of elephant relatives and the rapid radiation of African ungulates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (26): 10717–10721. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610717G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900251106. PMC 2705600. PMID 19549873.

- ^ Liu, Alexander G. S. C.; Seiffert, Erik R.; Simons, Elwyn L. (15 April 2008). "Stable isotope evidence for an amphibious phase in early proboscidean evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (15): 5786–5791. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.5786L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800884105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2311368. PMID 18413605.

- ^ Baleka, S.; Varela, L.; Tambusso, P. S.; Paijmans, J. L. A.; Mothé, D.; Stafford Jr., T. W.; Fariña, R. A.; Hofreiter, M. (2022). "Revisiting proboscidean phylogeny and evolution through total evidence and palaeogenetic analyses including Notiomastodon ancient DNA". iScience. 25 (1) 103559. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j3559B. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103559. PMC 8693454. PMID 34988402.

- ^ Benoit, J.; Lyras, G. A.; Schmitt, A.; Nxumalo, M.; Tabuce, R.; Obada, T.; Mararsecul, V.; Manger, P. (2023). "Paleoneurology of the Proboscidea (Mammalia, Afrotheria): Insights from Their Brain Endocast and Labyrinth". In Dozo, M. T.; Paulina-Carabajal, A.; Macrini, T. E.; Walsh, S. (eds.). Paleoneurology of Amniotes. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 579–644. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-13983-3_15. ISBN 978-3-031-13982-6.

- ^ a b c d Cantalapiedra, J. L.; Sanisidro, Ó.; Zhang, H.; Alberdi, M. T.; Prado, J. L.; Blanco, F.; Saarinen, J. (2021). "The rise and fall of proboscidean ecological diversity". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 5 (9): 1266–1272. Bibcode:2021NatEE...5.1266C. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01498-w. hdl:10261/249360. PMID 34211141. S2CID 235712060.

- ^ Saegusa, H.; Nakaya, H.; Kunimatsu, Y.; Nakatsukasa, M.; Tsujikawa, H.; Sawada, Y.; Saneyoshi, M. & Sakai, T. (2014). "Earliest elephantid remains from the late Miocene locality, Nakali, Kenya" (PDF). In Kostopoulos, D. S.; Vlachos, E. & Tsoukala, E. (eds.). VIth International Conference on Mammoths and Their Relatives. Vol. 102. Thessaloniki: School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. p. 175. ISBN 978-960-9502-14-6.

- ^ Lister, A. M. (2013). "The role of behaviour in adaptive morphological evolution of African proboscideans". Nature. 500 (7462): 331–334. Bibcode:2013Natur.500..331L. doi:10.1038/nature12275. PMID 23803767. S2CID 883007.

- ^ Sanders, William J. (7 July 2023). Evolution and Fossil Record of African Proboscidea (1 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 154, 220. doi:10.1201/b20016. ISBN 978-1-315-11891-8.

- ^ Iannucci, Alessio; Sardella, Raffaele (28 February 2023). "What Does the "Elephant-Equus" Event Mean Today? Reflections on Mammal Dispersal Events around the Pliocene-Pleistocene Boundary and the Flexible Ambiguity of Biochronology". Quaternary. 6 (1): 16. Bibcode:2023Quat....6...16I. doi:10.3390/quat6010016. hdl:11573/1680082.

- ^ Mothé, Dimila; dos Santos Avilla, Leonardo; Asevedo, Lidiane; Borges-Silva, Leon; Rosas, Mariane; Labarca-Encina, Rafael; Souberlich, Ricardo; Soibelzon, Esteban; Roman-Carrion, José Luis; Ríos, Sergio D.; Rincon, Ascanio D.; Cardoso de Oliveira, Gina; Pereira Lopes, Renato (30 September 2016). "Sixty years after 'The mastodonts of Brazil': The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae)" (PDF). Quaternary International. 443: 52–64. Bibcode:2017QuInt.443...52M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.08.028.

- ^ Lister, A. M.; Sher, A. V. (2015). "Evolution and dispersal of mammoths across the Northern Hemisphere". Science. 350 (6262): 805–809. Bibcode:2015Sci...350..805L. doi:10.1126/science.aac5660. PMID 26564853. S2CID 206639522.

- ^ Lister, A. M. (2004). "Ecological Interactions of Elephantids in Pleistocene Eurasia". Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books. pp. 53–60. ISBN 978-1-78570-965-4.

- ^ Rogers, R. L.; Slatkin, M. (2017). "Excess of genomic defects in a woolly mammoth on Wrangel island". PLOS Genetics. 13 (3) e1006601. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006601. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 5333797. PMID 28253255.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shoshani, J. (1998). "Understanding proboscidean evolution: a formidable task". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 13 (12): 480–487. Bibcode:1998TEcoE..13..480S. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01491-8. PMID 21238404.

- ^ Sukumar, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Romano, M.; Manucci, F.; Palombo, M. R. (2021). "The smallest of the largest: new volumetric body mass estimate and in-vivo restoration of the dwarf elephant Palaeoloxodon ex gr. P. falconeri from Spinagallo Cave (Sicily)". Historical Biology. 33 (3): 340–353. Bibcode:2021HBio...33..340R. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1617289. S2CID 181855906.

- ^ a b c d e Shoshani, pp. 38–41.

- ^ a b c d e f Shoshani, pp. 42–51.

- ^ a b c Shoshani, J.; Eisenberg, J. F. (1982). "Elephas maximus" (PDF). Mammalian Species (182): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504045. JSTOR 3504045. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Shoshani, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Somgrid, C. "Elephant Anatomy and Biology: Skeletal system". Elephant Research and Education Center, Department of Companion Animal and Wildlife Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University. Archived from the original on 13 June 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ Kingdon, p. 11.

- ^ Mole, Michael A.; Rodrigues Dáraujo, Shaun; Van Aarde, Rudi J.; Mitchell, Duncan; Fuller, Andrea (2018). "Savanna elephants maintain homeothermy under African heat". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 188 (5): 889–897. doi:10.1007/s00360-018-1170-5. PMID 30008137. S2CID 51626564. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Narasimhan, A. (2008). "Why do elephants have big ear flaps?". Resonance. 13 (7): 638–647. doi:10.1007/s12045-008-0070-5. S2CID 121443269.

- ^ Reuter, T.; Nummela, S.; Hemilä, S. (1998). "Elephant hearing" (PDF). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 104 (2): 1122–1123. Bibcode:1998ASAJ..104.1122R. doi:10.1121/1.423341. PMID 9714930. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2012.

- ^ Somgrid, C. "Elephant Anatomy and Biology: Special sense organs". Elephant Research and Education Center, Department of Companion Animal and Wildlife Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ Yokoyama, S.; Takenaka, N.; Agnew, D. W.; Shoshani, J. (2005). "Elephants and human color-blind deuteranopes have identical sets of visual pigments". Genetics. 170 (1): 335–344. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.039511. PMC 1449733. PMID 15781694.

- ^ a b Byrne, R. W.; Bates, L.; Moss C. J. (2009). "Elephant cognition in primate perspective". Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews. 4: 65–79. doi:10.3819/ccbr.2009.40009. hdl:10023/1612.

- ^ a b c d Shoshani, pp. 74–77.

- ^ a b c Martin, F.; Niemitz C. (2003). ""Right-trunkers" and "left-trunkers": side preferences of trunk movements in wild Asian elephants (Elephas maximus)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 117 (4): 371–379. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.117.4.371. PMID 14717638.

- ^ Dagenais, P; Hensman, S; Haechler, V; Milinkovitch, M. C. (2021). "Elephants evolved strategies reducing the biomechanical complexity of their trunk". Current Biology. 31 (21): 4727–4737. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E4727D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.029. PMID 34428468. S2CID 237273086.

- ^ Schulz, A. K.; Boyle, M; Boyle, C; Sordilla, S; Rincon, C; Hooper, K; Aubuchon, C; Reidenberg, J. S.; Higgins, C; Hu, D. L. (2022). "Skin wrinkles and folds enable asymmetric stretch in the elephant trunk". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (31) e2122563119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11922563S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2122563119. PMC 9351381. PMID 35858384.

- ^ Schulz, A. K.; Kaufmann, L. V.; Reveyaz, N; Ritter, C; Hildebrandt, T; Brecht, M (2024). "Elephants develop wrinkles through both form and function". Royal Society Open Science. 11 (10) 240851. Bibcode:2024RSOS...1140851S. doi:10.1098/rsos.240851. PMC 11461087. PMID 39386989.

- ^ Kingdon, p. 9.

- ^ a b Schulz, A. K.; Ning Wu, Jia; Sara Ha, S. Y.; Kim, G. (2021). "Suction feeding by elephants". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 18 (179). doi:10.1098/rsif.2021.0215. PMC 8169210. PMID 34062103.

- ^ a b West, J. B. (2002). "Why doesn't the elephant have a pleural space?". Physiology. 17 (2): 47–50. doi:10.1152/nips.01374.2001. PMID 11909991. S2CID 27321751.

- ^ a b Sukumar, p. 149.

- ^ Deiringer, Nora; Schneeweiß, Undine; Kaufmann, Lena V.; Eigen, Lennart; Speissegger, Celina; Gerhardt, Ben; Holtze, Susanne; Fritsch, Guido; Göritz, Frank; Becker, Rolf; Ochs, Andreas; Hildebrandt, Thomas; Brecht, Michael (8 June 2023). "The functional anatomy of elephant trunk whiskers". Communications Biology. 6 (1): 591. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-04945-5. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 10250425. PMID 37291455.

- ^ Cole, M. (14 November 1992). "Lead in lake blamed for floppy trunks". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ a b Shoshani, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Shoshani, pp. 71–74.

- ^ Sukumar, p. 120

- ^ Clutton-Brock, J. (1986). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. British Museum (Natural History). p. 208. ISBN 978-0-521-34697-9.

- ^ "Elephants Evolve Smaller Tusks Due to Poaching". Environmental News Network. 20 January 2008. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Under poaching pressure, elephants are evolving to lose their tusks". National Geographic. 9 November 2018. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Gray, R. (20 January 2008). "Why elephants are not so long in the tusk". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Chiyo, P. I.; Obanda, V.; Korir, D. K. (2015). "Illegal tusk harvest and the decline of tusk size in the African elephant". Ecology and Evolution. 5 (22): 5216–5229. Bibcode:2015EcoEv...5.5216C. doi:10.1002/ece3.1769. PMC 6102531. PMID 30151125.

- ^ Jachmann, H.; Berry, P. S. M.; Imae, H. (1995). "Tusklessness in African elephants: a future trend". African Journal of Ecology. 33 (3): 230–235. Bibcode:1995AfJEc..33..230J. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1995.tb00800.x.

- ^ Kurt, F.; Hartl, G.; Tiedemann, R. (1995). "Tuskless bulls in Asian elephant Elephas maximus. History and population genetics of a man-made phenomenon". Acta Theriol. 40: 125–144. doi:10.4098/at.arch.95-51.

- ^ a b Shoshani, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Myhrvold, C. L.; Stone, H. A.; Bou-Zeid, E. (10 October 2012). "What Is the Use of Elephant Hair?". PLOS ONE. 7 (10) e47018. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747018M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047018. PMC 3468452. PMID 23071700.

- ^ Lamps, L. W.; Smoller, B. R.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Slade, B. E.; Fritsch, G; Godwin, T. E. (2001). "Characterization of interdigital glands in the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus)". Research in Veterinary Science. 71 (3): 197–200. doi:10.1053/rvsc.2001.0508. PMID 11798294.

- ^ Wright, P. G.; Luck, C. P. (1984). "Do elephants need to sweat?". Journal of Zoology. 19 (4): 270–274. doi:10.1080/02541858.1984.11447892.

- ^ Spearman, R. I. C. (1970). "The epidermis and its keratinisation in the African Elephant (Loxodonta Africana)". Zoologica Africana. 5 (2): 327–338. doi:10.1080/00445096.1970.11447400.

- ^ Martins, António F.; Bennett, Nigel C.; Clavel, Sylvie; Groenewald, Herman; Hensman, Sean; Hoby, Stefan; Joris, Antoine; Manger, Paul R.; Milinkovitch, Michel C. (2018). "Locally-curved geometry generates bending cracks in the African elephant skin". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3865. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3865M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06257-3. PMC 6168576. PMID 30279508.

- ^ a b c Shoshani, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c Weissengruber, G. E.; Egger, G. F.; Hutchinson, J. R.; Groenewald, H. B.; Elsässer, L.; Famini, D.; Forstenpointner, G. (2006). "The structure of the cushions in the feet of African elephants (Loxodonta africana)". Journal of Anatomy. 209 (6): 781–792. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00648.x. PMC 2048995. PMID 17118065.

- ^ Shoshani, p. 74.

- ^ Hutchinson, J. R.; Delmer, C; Miller, C. E.; Hildebrandt, T; Pitsillides, A. A.; Boyde, A (2011). "From flat foot to fat foot: structure, ontogeny, function, and evolution of elephant "sixth toes"" (PDF). Science. 334 (6063): 1699–1703. Bibcode:2011Sci...334R1699H. doi:10.1126/science.1211437. PMID 22194576. S2CID 206536505.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, J. R.; Schwerda, D.; Famini, D. J.; Dale, R. H.; Fischer, M. S.; Kram, R. (2006). "The locomotor kinematics of Asian and African elephants: changes with speed and size". Journal of Experimental Biology. 209 (19): 3812–3827. Bibcode:2006JExpB.209.3812H. doi:10.1242/jeb.02443. PMID 16985198.

- ^ Hutchinson, J. R.; Famini, D.; Lair, R.; Kram, R. (2003). "Biomechanics: Are fast-moving elephants really running?". Nature. 422 (6931): 493–494. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..493H. doi:10.1038/422493a. PMID 12673241. S2CID 4403723. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Shoshani, p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shoshani, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b O'Connell, Caitlin (20 July 2016). "Elephant Don: The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse". University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-38005-6. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ Herbest, C. T.; Švec, J. G.; Lohscheller, J.; Frey, R.; Gumpenberger, M.; Stoeger, A.; Fitch, W. T. (2013). "Complex Vibratory Patterns in an Elephant Larynx". Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (21): 4054–4064. Bibcode:2013JExpB.216.4054H. doi:10.1242/jeb.091009. PMID 24133151.

- ^ a b Anon (2010). Mammal Anatomy: An Illustrated Guide. Marshall Cavendish. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7614-7882-9.

- ^ Yang, Patricia J.; Pham, Jonathan; Choo, Jerome; Hu, David L. (19 August 2014). "Duration of urination does not change with body size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (33): 11932–11937. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11111932Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402289111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4143032. PMID 24969420.

- ^ a b Murray E. Fowler; Susan K. Mikota (2006). Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants. John Wiley & Sons. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-8138-0676-1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Sharma, Virag; Lehmann, Thomas; Stuckas, Heiko; Funke, Liane; Hiller, Michael (2018). "Loss of RXFP2 and INSL3 genes in Afrotheria shows that testicular descent is the ancestral condition in placental mammals". PLOS Biology. 16 (6) e2005293. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2005293. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 6023123. PMID 29953435.

- ^ Short, R. V.; Mann, T.; Hay, Mary F. (1967). "Male reproductive organs of the African elephant, Loxodonta africana" (PDF). Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 13 (3): 517–536. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0130517. PMID 6029179. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ Shoshani, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e Eltringham, pp. 124–27.

- ^ Siegel, J. M. (2005). "Clues to the functions of mammalian sleep". Nature. 437 (7063): 1264–1271. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1264S. doi:10.1038/nature04285. PMC 8760626. PMID 16251951. S2CID 234089.

- ^ Sukumar, p. 159.

- ^ Sukumar, p. 174.

- ^ Hoare, B. (2009). Animal Migration: Remarkable Journeys in the Wild. University of California Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-520-25823-5.

- ^ a b c d Shoshani, pp. 226–29.

- ^ Campos-Arceiz, A.; Blake, S. (2011). "Mega-gardeners of the forest – the role of elephants in seed dispersal" (PDF). Acta Oecologica. 37 (6): 542–553. Bibcode:2011AcO....37..542C. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2011.01.014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2012.