Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

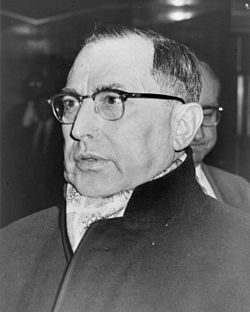

Joe Profaci

View on WikipediaGiuseppe "Joe" Profaci (Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe proˈfaːtʃi]; October 2, 1897 – June 6, 1962) was an Italian-American Cosa Nostra boss who was the founder of what became the Colombo crime family of New York City. Established in 1928, this was the last of the Five Families to be organized. He was the family's boss for over three decades.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Giuseppe Profaci was born in Villabate, in the Province of Palermo, Sicily, on October 2, 1897. In 1920, Profaci spent one year in prison in Palermo on theft charges.[1][2]

Family ties

[edit]Profaci's sons were Frank Profaci and John Profaci Sr. Frank eventually joined the Profaci crime family while John Sr. followed legitimate pursuits.[3] Two of Profaci's daughters married the sons of Detroit Partnership mobsters William Tocco and Joseph Zerilli.[4]

Profaci's brother was Salvatore Profaci, who served as his consigliere for years, and is known to have been heavily into dealing of pornographic materials. One of Profaci's brothers-in-law was Joseph Magliocco, who would eventually become Profaci's underboss. Profaci's niece Rosalie Profaci was married to Salvatore Bonanno, the son of Bonanno crime family boss Joseph Bonanno. Profaci was the uncle of Salvatore Profaci Jr., also a member of the Profaci crime family.[4]

Rosalie Profaci offered the following description of her uncle:

He was a flamboyant man who smoked big cigars, drove big black Cadillacs, and did things like buy tickets to a Broadway play for us cousins. But he didn't buy two or three or even four seats, he bought a whole row.[5]

Released from prison in 1921, Profaci emigrated to the United States, arriving in New York City on September 4. Profaci settled in Chicago, where he opened a grocery store and bakery. However, the business was unsuccessful, and in 1925, Profaci relocated to New York, where he entered the olive oil import business.[1] On September 27, 1927, Profaci became a United States citizen.[2] At some point after his move to Brooklyn, Profaci became involved with local gangs.

Rise to family boss

[edit]On December 5, 1928, Profaci attended a mob meeting in Cleveland, Ohio. The agenda of the meeting included resolving conflicts arising from assassinations, and a vote on recognition of the Profaci crime family in Brooklyn. The 1963 McClellan hearings introduced some erroneous facts about the origins of the Profaci family, one being that it was an offshoot of Maranzano's crime family.[1] His brother-in-law, Joe Magliocco, was Profaci's second-in-command.

Given Profaci's lack of experience in organized crime, it is unclear why the New York gangs gave him power in Brooklyn. Some speculated that Profaci received this position due to his family's status in Sicily, where they may have belonged to the Villabate Mafia. Profaci may have also benefited from contacts made through his olive oil business.[1] Cleveland police eventually raided the meeting and expelled the mobsters from Cleveland, but Profaci's business was accomplished.

By 1930, Profaci was controlling numbers, prostitution, loansharking, and narcotics trafficking in Brooklyn. In 1930, the Castellammarese War broke out in New York City. Some sources say that Profaci remained neutral, while others say that Profaci was firmly aligned with Castellammarese boss Salvatore Maranzano.[2] When the war finally ended in 1931, top mobster Charles "Lucky" Luciano reorganized the New York gangs into five organized crime families. At this point, Profaci was recognized as boss of what was now the Profaci crime family, with Magliocco as underboss and Salvatore Profaci as consigliere.

When Luciano created the National Crime Syndicate, also known as the Mafia Commission, he gave Profaci a seat on the governing board. Profaci's closest ally on the board was Bonanno, who would cooperate with Profaci over the next 30 years. Profaci was also allied with Stefano Magaddino, the boss of the Buffalo crime family.

Business and faith

[edit]Profaci obtained most of his wealth through traditional illegal enterprises such as protection rackets and extortion. However, to protect himself from federal tax evasion charges, Profaci still maintained his original olive oil business, known as Mamma Mia Importing Company, leading to his nickname as "Olive Oil King".[6] As the demand for olive oil skyrocketed after World War II, his business thrived. Profaci owned 20 other businesses that employed hundreds of workers in New York.[4]

Profaci owned a large house in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, a home in Miami Beach, Florida, and a 328-acre (1.33 km2) estate near Hightstown, New Jersey, which previously belonged to President Theodore Roosevelt. Profaci's estate had its own airstrip and a chapel with an altar that replicated one in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.[5]

Profaci was a devout Catholic who made generous cash donations to Catholic charities. A member of the Knights of Columbus, Profaci would invite priests to his estate to celebrate Mass. In May 1952, a thief stole valuable jeweled crowns from the Regina Pacis Votive shrine in Brooklyn. Profaci sent his men to recover the crowns and reportedly kill the thief. However, accounts of the thief being strangled with a rosary are unfounded.[5][7]

In 1949, the Vatican received a petition from a group of New York Catholics to confer a knighthood on Profaci. However, when the Brooklyn District Attorney complained about the move, the Vatican denied the petition.[8]

Legal problems

[edit]In 1953, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service sued Profaci for over $1.5 million in unpaid income taxes.[4] The taxes were still unpaid when Profaci died nine years later.[6]

In 1954, the US Department of Justice moved to revoke Profaci's citizenship. The government claimed that when Profaci entered the United States in 1921, he lied to immigration officials about having no arrest record in Italy. In 1960, a U.S. Court of Appeals reversed Profaci's deportation order, ending the legal action.[9]

In 1956, law enforcement recorded a phone conversation between Profaci and Antonio Cottone, a Sicilian mafioso, about exporting Sicilian oranges to the United States. In 1959, US Customs agents intercepted one of those orange crates in New York. The crate contained 90 wax oranges containing a total 110 pounds (50 kg) of pure heroin. Smugglers in Sicily had filled the hollow oranges with heroin until they weighed as much as real oranges, then packed them in the crate.[10] Profaci was never prosecuted for this crime.

In 1957, Profaci attended the Apalachin Conference, a national mob meeting, at the farm of mobster Joseph Barbara in Apalachin, New York. While the conference was in progress, New York State Troopers surrounded the farm and raided it. Profaci was one of over 60 mobsters arrested that day. On January 13, 1960, Profaci and 21 others were convicted of conspiracy and he was sentenced to five years in prison. However, on November 28, 1960, a United States Court of Appeals overturned the verdicts.[11]

First Colombo war

[edit]In contrast to Profaci's generosity to his relatives and the church, many of his men considered him miserly and mean with money. One reason for their rancor was that Profaci required each family member to pay him a $25 a month tithe, an old Sicilian gang custom. The money, which amounted to approximately $50,000 a month, was meant to support the families of mobsters in prison. However, most of this money stayed with Profaci. In addition, Profaci did not tolerate any dissent from his policies, and people who expressed discontent were murdered.[2]

On February 27, 1961, the Gallos, led by Joe Gallo, kidnapped four of Profaci's top men: underboss Magliocco, Frank Profaci (Joe Profaci's brother), capo Salvatore Musacchia and soldier John Scimone.[12] Profaci himself eluded capture and flew to sanctuary in Florida.[12] While holding the hostages, Larry and Albert Gallo sent Joe Gallo to California. The Gallos demanded a more favorable financial scheme for the hostages' release. Gallo wanted to kill one hostage and demand $100,000 before negotiations, but his brother Larry overruled him. After a few weeks of negotiation, Profaci made a deal with the Gallos.[13] Profaci's consigliere Charles "the Sidge" LoCicero negotiated with the Gallos and all the hostages were released peacefully.[14] However, Profaci had no intention of honoring this peace agreement. On August 20, 1961, Joseph Profaci ordered the murder of Gallo members Joseph "Joe Jelly" Gioielli and Larry Gallo. Gunmen allegedly murdered Gioielli after inviting him to go fishing.[12] Larry Gallo survived a strangulation attempt in the Sahara club of East Flatbush by Carmine Persico and Salvatore "Sally" D'Ambrosio after a police officer intervened.[12][15] The Gallo brothers had been previously aligned with Persico against Profaci and his loyalists;[12][15] The Gallos then began calling Persico "The Snake" after he had betrayed them.[15] the war continued on resulting in nine murders and three disappearances.[15] With the start of the gang war, the Gallo crew retreated to the Dormitory.[16]

Mob standoff

[edit]By 1962, Profaci's health was failing. In early 1962, Carlo Gambino and Lucchese crime family boss Tommy Lucchese tried to convince Profaci to resign to end the gang war. However, Profaci strongly suspected that the two bosses were secretly supporting the Gallo brothers and wanted to take control of his family. Profaci vehemently refused to resign; furthermore, he warned that any attempt to remove him would spark a wider gang war. Gambino and Lucchese did not pursue their efforts.[17]

Death

[edit]On June 6, 1962, Profaci died in South Side Hospital in Bay Shore, New York of liver cancer.[6] He is buried at Saint John Cemetery in the Middle Village section of Queens, in one of the largest mausoleums in the cemetery.[18]

After Profaci's death, Magliocco succeeded him as head of the family.[17] In late 1963, the Mafia Commission forced Magliocco out of office and installed Joseph Colombo as family boss.[19] At this point, the Profaci crime family became the Colombo crime family.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Critchley, David (2008). The origin of organized crime in America : the New York City Mafia, 1891-1931. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-99030-1.

- ^ a b c d Harrell, G.T. (2008). For members only : the story of the mob's secret judge : a true story. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4389-1388-9.

- ^ Goldstein, Joseph (December 12, 2010). "Godmother of real estate". New York Post. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d Abadinsky, Howard (2010). Organized crime (9th ed.). Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-495-59966-1.

profaci taxes.

- ^ a b c Rosenblum, Mort (1998). Olives : the life and lore of a noble fruit (1st paperback ed.). New York: North Point Press. ISBN 0-86547-526-1.

- ^ a b c "Profaci Dies of Cancer; Led Feuding Brooklyn Mob" (PDF). New York Times. June 8, 1962. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Dunleavy, Steven (July 12, 2004). "MAFIA BANNED MURDER - HALTED HITS UNDER HEAT". New York Post. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Sifakis, Carl (2005). The Mafia encyclopedia (3. ed.). New York: Facts on File. p. 365. ISBN 0-8160-5694-3.

- ^ "United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Joe Profaci". VLEX. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ "Covert Money, Power & Policy: Assassination". Archived from the original on 2002-03-29. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ Ranzal, Edward (November 29, 1960). "Civil Rights Cited: Judges Find Evidence Not Sufficient to Prove Crime" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Cage, Nicholas (July 17, 1972) "Part II The Mafia at War" New York pp.27-36

- ^ Sifakis, Carl (2005). The Mafia encyclopedia (3. ed.). New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-5694-3.

- ^ Capeci (2001), p.303

- ^ a b c d Raab (2006), pp.321-324

- ^ Cook, Fred J. (October 23, 1966). "Robin Hoods or Real Tough Boys:Larry Gallo, Crazy Joe, and Kid Blast" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Bruno, Anthony. "The Colombo Family: The Olive Oil King". TruTV Crime Library. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Guart, Al (July 7, 2001). "RESTING PLACES OF THE DONS". New York Post. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Bruno, Anthony. "TruTV Crime Library". The Colombo Family: Trouble and More Trouble. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Capeci, Jerry (2001). The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia. Indianapolis: Alpha Books. ISBN 0-02-864225-2.