Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kinetochore

View on Wikipedia

A kinetochore (/kɪˈnɛtəkɔːr/, /-ˈniːtəkɔːr/) is a flared oblique-shaped protein structure associated with duplicated chromatids in eukaryotic cells where the spindle fibers, which can be thought of as the ropes pulling chromosomes apart, attach during cell division to pull sister chromatids apart.[1] The kinetochore assembles on the centromere and links the chromosome to microtubule polymers from the mitotic spindle during mitosis and meiosis. The term kinetochore was first used in a footnote in a 1934 Cytology book by Lester W. Sharp[2] and commonly accepted in 1936.[3] Sharp's footnote reads: "The convenient term kinetochore (= movement place) has been suggested to the author by J. A. Moore", likely referring to John Alexander Moore who had joined Columbia University as a freshman in 1932.[4]

Monocentric organisms, including vertebrates, fungi, and most plants, have a single centromeric region on each chromosome which assembles a single, localized kinetochore. Holocentric organisms, such as nematodes and some plants, assemble a kinetochore along the entire length of a chromosome.[5]

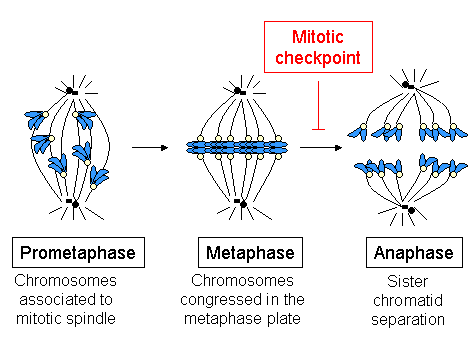

Kinetochores start, control, and supervise the striking movements of chromosomes during cell division. During mitosis, which occurs after the amount of DNA is doubled in each chromosome (while maintaining the same number of chromosomes) in S phase, two sister chromatids are held together by a centromere. Each chromatid has its own kinetochore, which face in opposite directions and attach to opposite poles of the mitotic spindle apparatus. Following the transition from metaphase to anaphase, the sister chromatids separate from each other, and the individual kinetochores on each chromatid drive their movement to the spindle poles that will define the two new daughter cells. The kinetochore is therefore essential for the chromosome segregation that is classically associated with mitosis and meiosis.

Structure

[edit]The kinetochore contains two regions:

- an inner kinetochore, which is tightly associated with the centromere DNA and assembled in a specialized form of chromatin that persists throughout the cell cycle;

- an outer kinetochore, which interacts with microtubules; the outer kinetochore is a very dynamic structure with many identical components, which are assembled and functional only during cell division.

Even the simplest kinetochores consist of more than 19 different proteins. Many of these proteins are conserved between eukaryotic species, including a specialized histone H3 variant (called CENP-A or CenH3) which helps the kinetochore associate with DNA. Other proteins in the kinetochore adhere it to the microtubules (MTs) of the mitotic spindle. There are also motor proteins, including both dynein and kinesin, which generate forces that move chromosomes during mitosis. Other proteins, such as Mad2, monitor the microtubule attachment as well as the tension between sister kinetochores and activate the spindle checkpoint to arrest the cell cycle when either of these is absent.[6] The actual set of genes essential for kinetochore function varies from one species to another.[7][8]

Kinetochore functions include anchoring of chromosomes to MTs in the spindle, verification of anchoring, activation of the spindle checkpoint and participation in the generation of force to propel chromosome movement during cell division.[9] On the other hand, microtubules are metastable polymers made of α- and β-tubulin, alternating between growing and shrinking phases, a phenomenon known as dynamic instability.[10] MTs are highly dynamic structures, whose behavior is integrated with kinetochore function to control chromosome movement and segregation. It has also been reported that the kinetochore organization differs between mitosis and meiosis and the integrity of meiotic kinetochore is essential for meiosis specific events such as pairing of homologous chromosomes, sister kinetochore monoorientation, protection of centromeric cohesin and spindle-pole body cohesion and duplication.[11][12]

In animal cells

[edit]The kinetochore is composed of several layers, observed initially by conventional fixation and staining methods of electron microscopy,[13][14] (reviewed by C. Rieder in 1982[15]) and more recently by rapid freezing and substitution.[16]

The deepest layer in the kinetochore is the inner plate, which is organized on a chromatin structure containing nucleosomes presenting a specialized histone (named CENP-A, which substitutes histone H3 in this region), auxiliary proteins, and DNA. DNA organization in the centromere (satellite DNA) is one of the least understood aspects of vertebrate kinetochores. The inner plate appears like a discrete heterochromatin domain throughout the cell cycle.

External to the inner plate is the outer plate, which is composed mostly of proteins. This structure is assembled on the surface of the chromosomes only after the nuclear envelope breaks down.[13] The outer plate in vertebrate kinetochores contains about 20 anchoring sites for MTs (+) ends (named kMTs, after kinetochore MTs), whereas a kinetochore's outer plate in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) contains only one anchoring site.

The outermost domain in the kinetochore forms a fibrous corona, which can be visualized by conventional microscopy, yet only in the absence of MTs. This corona is formed by a dynamic network of resident and temporary proteins implicated in the spindle checkpoint, in microtubule anchoring, and in the regulation of chromosome behavior.

During mitosis, each sister chromatid forming the complete chromosome has its own kinetochore. Distinct sister kinetochores can be observed at first at the end of G2 phase in cultured mammalian cells.[17] These early kinetochores show a mature laminar structure before the nuclear envelope breaks down.[18] The molecular pathway for kinetochore assembly in higher eukaryotes has been studied using gene knockouts in mice and in cultured chicken cells, as well as using RNA interference (RNAi) in C. elegans, Drosophila and human cells, yet no simple linear route can describe the data obtained so far.[citation needed]

The first protein to be assembled on the kinetochore is CENP-A (Cse4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae). This protein is a specialized isoform of histone H3.[19] CENP-A is required for incorporation of the inner kinetochore proteins CENP-C, CENP-H and CENP-I/MIS6.[20][21][22][23][24] The relation of these proteins in the CENP-A-dependent pathway is not completely defined. For instance, CENP-C localization requires CENP-H in chicken cells, but it is independent of CENP-I/MIS6 in human cells. In C. elegans and metazoa, the incorporation of many proteins in the outer kinetochore depends ultimately on CENP-A.

Kinetochore proteins can be grouped according to their concentration at kinetochores during mitosis: some proteins remain bound throughout cell division, whereas some others change in concentration. Furthermore, they can be recycled in their binding site on kinetochores either slowly (they are rather stable) or rapidly (dynamic).

- Proteins whose levels remain stable from prophase until late anaphase include constitutive components of the inner plate and the stable components of the outer kinetocore, such as the Ndc80 complex,[25][26] KNL/KBP proteins (kinetochore-null/KNL-binding protein),[27] MIS proteins[27] and CENP-F.[28][29] Together with the constitutive components, these proteins seem to organize the nuclear core of the inner and outer structures in the kinetochore.

- The dynamic components that vary in concentration on kinetochores during mitosis include the molecular motors CENP-E and dynein (as well as their target components ZW10 and ROD), and the spindle checkpoint proteins (such as Mad1, Mad2, BubR1 and Cdc20). These proteins assemble on the kinetochore in high concentrations in the absence of microtubules; however, the higher the number of MTs anchored to the kinetochore, the lower the concentrations of these proteins.[30] At metaphase, CENP-E, Bub3 and Bub1 levels diminish by a factor of about three to four as compared with free kinetochores, whereas dynein/dynactin, Mad1, Mad2 and BubR1 levels are reduced by a factor of more than 10 to 100.[30][31][32][33]

- Whereas the spindle checkpoint protein levels present in the outer plate diminish as MTs anchor,[33] other components such as EB1, APC and proteins in the Ran pathway (RanGap1 and RanBP2) associate to kinetochores only when MTs are anchored.[34][35][36][37] This may belong to a mechanism in the kinetochore to recognize the microtubules' plus-end (+), ensuring their proper anchoring and regulating their dynamic behavior as they remain anchored.

A 2010 study used a complex method (termed "multiclassifier combinatorial proteomics" or MCCP) to analyze the proteomic composition of vertebrate chromosomes, including kinetochores.[38] Although this study does not include a biochemical enrichment for kinetochores, obtained data include all the centromeric subcomplexes, with peptides from all 125 known centromeric proteins. According to this study, there are still about one hundred unknown kinetochore proteins, doubling the known structure during mitosis, which confirms the kinetochore as one of the most complex cellular substructures. Consistently, a comprehensive literature survey indicated that there had been at least 196 human proteins already experimentally shown to be localized at kinetochores.[39]

Function

[edit]The number of microtubules attached to one kinetochore is variable: in Saccharomyces cerevisiae only one MT binds each kinetochore, whereas in mammals there can be 15–35 MTs bound to each kinetochore.[40] However, not all the MTs in the spindle attach to one kinetochore. There are MTs that extend from one centrosome to the other (and they are responsible for spindle length) and some shorter ones are interdigitated between the long MTs. Professor B. Nicklas (Duke University), showed that, if one breaks down the MT-kinetochore attachment using a laser beam, chromatids can no longer move, leading to an abnormal chromosome distribution.[41] These experiments also showed that kinetochores have polarity, and that kinetochore attachment to MTs emanating from one or the other centrosome will depend on its orientation. This specificity guarantees that only one chromatid will move to each spindle side, thus ensuring the correct distribution of the genetic material. Thus, one of the basic functions of the kinetochore is the MT attachment to the spindle, which is essential to correctly segregate sister chromatids. If anchoring is incorrect, errors may ensue, generating aneuploidy, with catastrophic consequences for the cell. To prevent this from happening, there are mechanisms of error detection and correction (as the spindle assembly checkpoint), whose components reside also on the kinetochores. The movement of one chromatid towards the centrosome is produced primarily by MT depolymerization in the binding site with the kinetochore. These movements require also force generation, involving molecular motors likewise located on the kinetochores.

Chromosome anchoring to MTs in the mitotic spindle

[edit]Capturing MTs

[edit]

During the synthesis phase (S phase) in the cell cycle, the centrosome starts to duplicate. Just at the beginning of mitosis, both centrioles in each centrosome reach their maximal length, centrosomes recruit additional material and their nucleation capacity for microtubules increases. As mitosis progresses, both centrosomes separate to establish the mitotic spindle.[42] In this way, the spindle in a mitotic cell has two poles emanating microtubules. Microtubules are long proteic filaments with asymmetric extremes, a "minus"(-) end relatively stable next to the centrosome, and a "plus"(+) end enduring alternate phases of growing-shrinking, exploring the center of the cell. During this searching process, a microtubule may encounter and capture a chromosome through the kinetochore.[43][44] Microtubules that find and attach a kinetochore become stabilized, whereas those microtubules remaining free are rapidly depolymerized.[45] As chromosomes have two kinetochores associated back-to-back (one on each sister chromatid), when one of them becomes attached to the microtubules generated by one of the cellular poles, the kinetochore on the sister chromatid becomes exposed to the opposed pole; for this reason, most of the times the second kinetochore becomes attached to the microtubules emanating from the opposing pole,[46] in such a way that chromosomes are now bi-oriented, one fundamental configuration (also termed amphitelic) to ensure the correct segregation of both chromatids when the cell will divide.[47][48]

When just one microtubule is anchored to one kinetochore, it starts a rapid movement of the associated chromosome towards the pole generating that microtubule. This movement is probably mediated by the motor activity towards the "minus" (-) of the motor protein cytoplasmic dynein,[49][50] which is very concentrated in the kinetochores not anchored to MTs.[51] The movement towards the pole is slowed down as far as kinetochores acquire kMTs (MTs anchored to kinetochores) and the movement becomes directed by changes in kMTs length. Dynein is released from kinetochores as they acquire kMTs[30] and, in cultured mammalian cells, it is required for the spindle checkpoint inactivation, but not for chromosome congression in the spindle equator, kMTs acquisition or anaphase A during chromosome segregation.[52] In higher plants or in yeast there is no evidence of dynein, but other kinesins towards the (-) end might compensate for the lack of dynein.

Another motor protein implicated in the initial capture of MTs is CENP-E; this is a high molecular weight kinesin associated with the fibrous corona at mammalian kinetochores from prometaphase until anaphase.[53] In cells with low levels of CENP-E, chromosomes lack this protein at their kinetochores, which quite often are defective in their ability to congress at the metaphase plate. In this case, some chromosomes may remain chronically mono-oriented (anchored to only one pole), although most chromosomes may congress correctly at the metaphase plate.[54]

It is widely accepted that the kMTs fiber (the bundle of microtubules bound to the kinetochore) is originated by the capture of MTs polymerized at the centrosomes and spindle poles in mammalian cultured cells.[43] However, MTs directly polymerized at kinetochores might also contribute significantly.[55] The manner in which the centromeric region or kinetochore initiates the formation of kMTs and the frequency at which this happens are important questions,[according to whom?] because this mechanism may contribute not only to the initial formation of kMTs, but also to the way in which kinetochores correct defective anchoring of MTs and regulate the movement along kMTs.

Role of Ndc80 complex

[edit]MTs associated to kinetochores present special features: compared to free MTs, kMTs are much more resistant to cold-induced depolymerization, high hydrostatic pressures or calcium exposure.[56] Furthermore, kMTs are recycled much more slowly than astral MTs and spindle MTs with free (+) ends, and if kMTs are released from kinetochores using a laser beam, they rapidly depolymerize.[41]

When it was clear that neither dynein nor CENP-E is essential for kMTs formation, other molecules should be responsible for kMTs stabilization. Pioneer genetic work in yeast revealed the relevance of the Ndc80 complex in kMTs anchoring.[25][57][58][59] In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Ndc80 complex has four components: Ndc80p, Nuf2p, Spc24p and Spc25p. Mutants lacking any of the components of this complex show loss of the kinetochore-microtubule connection, although kinetochore structure is not completely lost.[25][57] Yet mutants in which kinetochore structure is lost (for instance Ndc10 mutants in yeast[60]) are deficient both in the connection to microtubules and in the ability to activate the spindle checkpoint, probably because kinetochores work as a platform in which the components of the response are assembled.

The Ndc80 complex is highly conserved and it has been identified in S. pombe, C. elegans, Xenopus, chicken and humans.[25][26][57][61][62][63][64] Studies on Hec1 (highly expressed in cancer cells 1), the human homolog of Ndc80p, show that it is important for correct chromosome congression and mitotic progression, and that it interacts with components of the cohesin and condensin complexes.[65]

Different laboratories have shown that the Ndc80 complex is essential for stabilization of the kinetochore-microtubule anchoring, required to support the centromeric tension implicated in the establishment of the correct chromosome congression in high eukaryotes.[26][62][63][64] Cells with impaired function of Ndc80 (using RNAi, gene knockout, or antibody microinjection) have abnormally long spindles, lack of tension between sister kinetochores, chromosomes unable to congregate at the metaphase plate and few or any associated kMTs.

There is a variety of strong support for the ability of the Ndc80 complex to directly associate with microtubules and form the core conserved component of the kinetochore-microtubule interface.[66] However, formation of robust kinetochore-microtubule interactions may also require the function of additional proteins. In yeast, this connection requires the presence of the complex Dam1-DASH-DDD. Some members of this complex bind directly to MTs, whereas some others bind to the Ndc80 complex.[58][59][67] This means that the complex Dam1-DASH-DDD might be an essential adapter between kinetochores and microtubules. However, in animals an equivalent complex has not been identified, and this question remains under intense investigation.

Verification of kinetochore–MT anchoring

[edit]During S-Phase, the cell duplicates all the genetic information stored in the chromosomes, in the process termed DNA replication. At the end of this process, each chromosome includes two sister chromatids, which are two complete and identical DNA molecules. Both chromatids remain associated by cohesin complexes until anaphase, when chromosome segregation occurs. If chromosome segregation happens correctly, each daughter cell receives a complete set of chromatids, and for this to happen each sister chromatid has to anchor (through the corresponding kinetochore) to MTs generated in opposed poles of the mitotic spindle. This configuration is termed amphitelic or bi-orientation.

However, during the anchoring process some incorrect configurations may also appear:[68]

- monotelic: only one of the chromatids is anchored to MTs, the second kinetochore is not anchored; in this situation, there is no centromeric tension, and the spindle checkpoint is activated, delaying entry in anaphase and allowing time for the cell to correct the error. If it is not corrected, the unanchored chromatid might randomly end in any of the two daughter cells, generating aneuploidy: one daughter cell would have chromosomes in excess and the other would lack some chromosomes.

- syntelic: both chromatids are anchored to MTs emanating from the same pole; this situation does not generate centromeric tension either, and the spindle checkpoint will be activated. If it is not corrected, both chromatids will end in the same daughter cell, generating aneuploidy.

- merotelic: at least one chromatid is anchored simultaneously to MTs emanating from both poles. This situation generates centromeric tension, and for this reason the spindle checkpoint is not activated. If it is not corrected, the chromatid bound to both poles will remain as a lagging chromosome at anaphase, and finally will be broken in two fragments, distributed between the daughter cells, generating aneuploidy.

Both the monotelic and the syntelic configurations fail to generate centromeric tension and are detected by the spindle checkpoint. In contrast, the merotelic configuration is not detected by this control mechanism. However, most of these errors are detected and corrected before the cell enters in anaphase.[68] A key factor in the correction of these anchoring errors is the chromosomal passenger complex, which includes the kinase protein Aurora B, its target and activating subunit INCENP and two other subunits, Survivin and Borealin/Dasra B (reviewed by Adams and collaborators in 2001[69]). Cells in which the function of this complex has been abolished by dominant negative mutants, RNAi, antibody microinjection or using selective drugs, accumulate errors in chromosome anchoring. Many studies have shown that Aurora B is required to destabilize incorrect anchoring kinetochore-MT, favoring the generation of amphitelic connections. Aurora B homolog in yeast (Ipl1p) phosphorilates some kinetochore proteins, such as the constitutive protein Ndc10p and members of the Ndc80 and Dam1-DASH-DDD complexes.[70] Phosphorylation of Ndc80 complex components produces destabilization of kMTs anchoring. It has been proposed that Aurora B localization is important for its function: as it is located in the inner region of the kinetochore (in the centromeric heterochromatin), when the centromeric tension is established sister kinetochores separate, and Aurora B cannot reach its substrates, so that kMTs are stabilized. Aurora B is frequently overexpressed in several cancer types, and it is currently a target for the development of anticancer drugs.[71]

Spindle checkpoint activation

[edit]The spindle checkpoint, or SAC (for spindle assembly checkpoint), also known as the mitotic checkpoint, is a cellular mechanism responsible for detection of:

- correct assembly of the mitotic spindle;

- attachment of all chromosomes to the mitotic spindle in a bipolar manner;

- congression of all chromosomes at the metaphase plate.

When just one chromosome (for any reason) remains lagging during congression, the spindle checkpoint machinery generates a delay in cell cycle progression: the cell is arrested, allowing time for repair mechanisms to solve the detected problem. After some time, if the problem has not been solved, the cell will be targeted for apoptosis (programmed cell death), a safety mechanism to avoid the generation of aneuploidy, a situation which generally has dramatic consequences for the organism.

Whereas structural centromeric proteins (such as CENP-B), remain stably localized throughout mitosis (including during telophase), the spindle checkpoint components are assembled on the kinetochore in high concentrations in the absence of microtubules, and their concentrations decrease as the number of microtubules attached to the kinetochore increases.[30]

At metaphase, CENP-E, Bub3 and Bub1 levels decreases 3 to 4 fold as compared to the levels at unattached kinetochores, whereas the levels of dynein/dynactin, Mad1, Mad2 and BubR1 decrease >10-100 fold.[30][31][32][33] Thus at metaphase, when all chromosomes are aligned at the metaphase plate, all checkpoint proteins are released from the kinetochore. The disappearance of the checkpoint proteins out of the kinetochores indicates the moment when the chromosome has reached the metaphase plate and is under bipolar tension. At this moment, the checkpoint proteins that bind to and inhibit Cdc20 (Mad1-Mad2 and BubR1), release Cdc20, which binds and activates APC/CCdc20, and this complex triggers sister chromatids separation and consequently anaphase entry.

Several studies indicate that the Ndc80 complex participates in the regulation of the stable association of Mad1-Mad2 and dynein with kinetochores.[26][63][64] Yet the kinetochore associated proteins CENP-A, CENP-C, CENP-E, CENP-H and BubR1 are independent of Ndc80/Hec1. The prolonged arrest in prometaphase observed in cells with low levels of Ndc80/Hec1 depends on Mad2, although these cells show low levels of Mad1, Mad2 and dynein on kinetochores (<10-15% in relation to unattached kinetochores). However, if both Ndc80/Hec1 and Nuf2 levels are reduced, Mad1 and Mad2 completely disappear from the kinetochores and the spindle checkpoint is inactivated.[72]

Shugoshin (Sgo1, MEI-S332 in Drosophila melanogaster[73]) are centromeric proteins which are essential to maintain cohesin bound to centromeres until anaphase. The human homolog, hsSgo1, associates with centromeres during prophase and disappears when anaphase starts.[74] When Shugoshin levels are reduced by RNAi in HeLa cells, cohesin cannot remain on the centromeres during mitosis, and consequently sister chromatids separate synchronically before anaphase initiates, which triggers a long mitotic arrest.

On the other hand, Dasso and collaborators have found that proteins involved in the Ran cycle can be detected on kinetochores during mitosis: RanGAP1 (a GTPase activating protein which stimulates the conversion of Ran-GTP in Ran-GDP) and the Ran binding protein called RanBP2/Nup358.[75] During interphase, these proteins are located at the nuclear pores and participate in the nucleo-cytoplasmic transport. Kinetochore localization of these proteins seem to be functionally significant, because some treatments that increase the levels of Ran-GTP inhibit kinetochore release of Bub1, Bub3, Mad2 and CENP-E.[76]

Orc2 (a protein that belongs to the origin recognition complex -ORC- implicated in DNA replication initiation during S phase) is also localized at kinetochores during mitosis in human cells;[77] in agreement with this localization, some studies indicate that Orc2 in yeast is implicated in sister chromatids cohesion, and when it is eliminated from the cell, spindle checkpoint activation ensues.[78] Some other ORC components (such orc5 in S. pombe) have been also found to participate in cohesion.[79] However, ORC proteins seem to participate in a molecular pathway which is additive to cohesin pathway, and it is mostly unknown.

Force generation to propel chromosome movement

[edit]Most chromosome movements in relation to spindle poles are associated to lengthening and shortening of kMTs. One of the features of kinetochores is their capacity to modify the state of their associated kMTs (around 20) from a depolymerization state at their (+) end to polymerization state. This allows the kinetochores from cells at prometaphase to show "directional instability",[80] changing between persistent phases of movement towards the pole (poleward) or inversed (anti-poleward), which are coupled with alternating states of kMTs depolymerization and polymerization, respectively. This kinetochore bi-stability seem to be part of a mechanism to align the chromosomes at the equator of the spindle without losing the mechanic connection between kinetochores and spindle poles. It is thought that kinetochore bi-stability is based upon the dynamic instability of the kMTs (+) end, and it is partially controlled by the tension present at the kinetochore. In mammalian cultured cells, a low tension at kinetochores promotes change towards kMTs depolymerization, and high tension promotes change towards kMTs polymerization.[81][82]

Kinetochore proteins and proteins binding to MTs (+) end (collectively called +TIPs) regulate kinetochore movement through the kMTs (+) end dynamics regulation.[83] However, the kinetochore-microtubule interface is highly dynamic, and some of these proteins seem to be bona fide components of both structures. Two groups of proteins seem to be particularly important: kinesins which work like depolymerases, such as KinI kinesins; and proteins bound to MT (+) ends, +TIPs, promoting polymerization, perhaps antagonizing the depolymerases effect.[84]

- KinI kinesins are named "I" because they present an internal motor domain, which uses ATP to promote depolymerization of tubulin polymer, the microtubule. In vertebrates, the most important KinI kinesin controlling the dynamics of the (+) end assembly is MCAK.[85] However, it seems that there are other kinesins implicated.

- There are two groups of +TIPs with kinetochore functions.

- The first one includes the protein adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and the associated protein EB1, which need MTs to localize on the kinetochores. Both proteins are required for correct chromosome segregation.[86] EB1 binds only to MTs in polymerizing state, suggesting that it promotes kMTs stabilization during this phase.

- The second group of +TIPs includes proteins which can localize on kinetochores even in absence of MTs. In this group there are two proteins that have been widely studied: CLIP-170 and their associated proteins CLASPs (CLIP-associated proteins). CLIP-170 role at kinetochores is unknown, but the expression of a dominant negative mutant produces a prometaphase delay,[87] suggesting that it has an active role in chromosome alignment. CLASPs proteins are required for chromosome alignment and maintenance of a bipolar spindle in Drosophila, humans and yeast.[88][89]

References

[edit]- ^ Santaguida S, Musacchio A (September 2009). "The life and miracles of kinetochores". The EMBO Journal. 28 (17): 2511–31. doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.173. PMC 2722247. PMID 19629042.

- ^ Sharp LW (1934). Introduction to cytology (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, inc. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.6429.

- ^ Schrader F (1936-06-01). "The kinetochore or spindle fibre locus in amphiuma tridactylum". The Biological Bulletin. 70 (3): 484–498. doi:10.2307/1537304. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1537304.

- ^ Kops GJ, Saurin AT, Meraldi P (July 2010). "Finding the middle ground: how kinetochores power chromosome congression". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 67 (13): 2145–61. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0321-y. PMC 2883098. PMID 20232224.

- ^ Albertson DG, Thomson JN (May 1993). "Segregation of holocentric chromosomes at meiosis in the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans". Chromosome Research. 1 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1007/BF00710603. PMID 8143084. S2CID 5644126.

- ^ Peter De Wulf, William C. Earnshaw, The Kinetochore: From Molecular Discoveries to Cancer Therapy

- ^ van Hooff JJ, Tromer E, van Wijk LM, Snel B, Kops GJ (September 2017). "Evolutionary dynamics of the kinetochore network in eukaryotes as revealed by comparative genomics". EMBO Reports. 18 (9): 1559–1571. doi:10.15252/embr.201744102. PMC 5579357. PMID 28642229.

- ^ Vijay N (2020-09-29). "Loss of inner kinetochore genes is associated with the transition to an unconventional point centromere in budding yeast". PeerJ. 8 e10085. doi:10.7717/peerj.10085. PMC 7531349. PMID 33062452.

- ^ a b Maiato H, DeLuca J, Salmon ED, Earnshaw WC (November 2004). "The dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface". Journal of Cell Science. 117 (Pt 23): 5461–77. doi:10.1242/jcs.01536. hdl:10216/35050. PMID 15509863.

- ^ Mitchison T, Kirschner M (1984). "Dynamic instability of microtubule growth" (PDF). Nature. 312 (5991): 237–42. Bibcode:1984Natur.312..237M. doi:10.1038/312237a0. PMID 6504138. S2CID 30079133. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ^ Mehta GD, Agarwal M, Ghosh SK (March 2014). "Functional characterization of kinetochore protein, Ctf19 in meiosis I: an implication of differential impact of Ctf19 on the assembly of mitotic and meiotic kinetochores in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Molecular Microbiology. 91 (6): 1179–99. doi:10.1111/mmi.12527. PMID 24446862.

- ^ Agarwal M, Mehta G, Ghosh SK (March 2015). "Role of Ctf3 and COMA subcomplexes in meiosis: Implication in maintaining Cse4 at the centromere and numeric spindle poles". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1853 (3): 671–84. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.12.032. PMID 25562757.

- ^ a b Brinkley BR, Stubblefield E (1966). "The fine structure of the kinetochore of a mammalian cell in vitro". Chromosoma. 19 (1): 28–43. doi:10.1007/BF00332792. PMID 5912064. S2CID 43314146.

- ^ Jokelainen PT (July 1967). "The ultrastructure and spatial organization of the metaphase kinetochore in mitotic rat cells". Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 19 (1): 19–44. doi:10.1016/S0022-5320(67)80058-3. PMID 5339062.

- ^ Rieder CL (1982). The Formation, Structure, and Composition of the Mammalian Kinetochore and Kinetochore Fiber. International Review of Cytology. Vol. 79. pp. 1–58. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)61672-1. ISBN 978-0-12-364479-4. PMID 6185450.

- ^ McEwen BF, Hsieh CE, Mattheyses AL, Rieder CL (December 1998). "A new look at kinetochore structure in vertebrate somatic cells using high-pressure freezing and freeze substitution". Chromosoma. 107 (6–7): 366–75. doi:10.1007/s004120050320. PMC 2905855. PMID 9914368.

- ^ Brenner S, Pepper D, Berns MW, Tan E, Brinkley BR (October 1981). "Kinetochore structure, duplication, and distribution in mammalian cells: analysis by human autoantibodies from scleroderma patients". The Journal of Cell Biology. 91 (1): 95–102. doi:10.1083/jcb.91.1.95. PMC 2111947. PMID 7298727.

- ^ Pluta AF, Mackay AM, Ainsztein AM, Goldberg IG, Earnshaw WC (December 1995). "The centromere: hub of chromosomal activities". Science. 270 (5242): 1591–4. Bibcode:1995Sci...270.1591P. doi:10.1126/science.270.5242.1591. PMID 7502067. S2CID 44632550.

- ^ Palmer DK, O'Day K, Trong HL, Charbonneau H, Margolis RL (May 1991). "Purification of the centromere-specific protein CENP-A and demonstration that it is a distinctive histone". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 88 (9): 3734–8. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.3734P. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.9.3734. PMC 51527. PMID 2023923.

- ^ Howman EV, Fowler KJ, Newson AJ, Redward S, MacDonald AC, Kalitsis P, Choo KH (February 2000). "Early disruption of centromeric chromatin organization in centromere protein A (Cenpa) null mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (3): 1148–53. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.1148H. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.3.1148. PMC 15551. PMID 10655499.

- ^ Oegema K, Desai A, Rybina S, Kirkham M, Hyman AA (June 2001). "Functional analysis of kinetochore assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans". The Journal of Cell Biology. 153 (6): 1209–26. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.6.1209. PMC 2192036. PMID 11402065.

- ^ Van Hooser AA, Ouspenski II, Gregson HC, Starr DA, Yen TJ, Goldberg ML, et al. (October 2001). "Specification of kinetochore-forming chromatin by the histone H3 variant CENP-A". Journal of Cell Science. 114 (Pt 19): 3529–42. doi:10.1242/jcs.114.19.3529. PMID 11682612.

- ^ Fukagawa T, Mikami Y, Nishihashi A, Regnier V, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y, et al. (August 2001). "CENP-H, a constitutive centromere component, is required for centromere targeting of CENP-C in vertebrate cells". The EMBO Journal. 20 (16): 4603–17. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.16.4603. PMC 125570. PMID 11500386.

- ^ Goshima G, Kiyomitsu T, Yoda K, Yanagida M (January 2003). "Human centromere chromatin protein hMis12, essential for equal segregation, is independent of CENP-A loading pathway". The Journal of Cell Biology. 160 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1083/jcb.200210005. PMC 2172742. PMID 12515822.

- ^ a b c d Wigge PA, Kilmartin JV (January 2001). "The Ndc80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere components and has a function in chromosome segregation". The Journal of Cell Biology. 152 (2): 349–60. doi:10.1083/jcb.152.2.349. PMC 2199619. PMID 11266451.

- ^ a b c d DeLuca JG, Moree B, Hickey JM, Kilmartin JV, Salmon ED (November 2002). "hNuf2 inhibition blocks stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment and induces mitotic cell death in HeLa cells". The Journal of Cell Biology. 159 (4): 549–55. doi:10.1083/jcb.200208159. PMC 2173110. PMID 12438418.

- ^ a b Cheeseman IM, Niessen S, Anderson S, Hyndman F, Yates JR, Oegema K, Desai A (September 2004). "A conserved protein network controls assembly of the outer kinetochore and its ability to sustain tension". Genes & Development. 18 (18): 2255–68. doi:10.1101/gad.1234104. PMC 517519. PMID 15371340.

- ^ Rattner JB, Rao A, Fritzler MJ, Valencia DW, Yen TJ (1993). "CENP-F is a .ca 400 kDa kinetochore protein that exhibits a cell-cycle dependent localization". Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 26 (3): 214–26. doi:10.1002/cm.970260305. PMID 7904902.

- ^ Liao H, Winkfein RJ, Mack G, Rattner JB, Yen TJ (August 1995). "CENP-F is a protein of the nuclear matrix that assembles onto kinetochores at late G2 and is rapidly degraded after mitosis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 130 (3): 507–18. doi:10.1083/jcb.130.3.507. PMC 2120529. PMID 7542657.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffman DB, Pearson CG, Yen TJ, Howell BJ, Salmon ED (July 2001). "Microtubule-dependent changes in assembly of microtubule motor proteins and mitotic spindle checkpoint proteins at PtK1 kinetochores". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 12 (7): 1995–2009. doi:10.1091/mbc.12.7.1995. PMC 55648. PMID 11451998.

- ^ a b King SM (March 2000). "The dynein microtubule motor". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1496 (1): 60–75. doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(00)00009-4. PMID 10722877.

- ^ a b Howell BJ, Moree B, Farrar EM, Stewart S, Fang G, Salmon ED (June 2004). "Spindle checkpoint protein dynamics at kinetochores in living cells". Current Biology. 14 (11): 953–64. Bibcode:2004CBio...14..953H. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.053. PMID 15182668.

- ^ a b c Shah JV, Botvinick E, Bonday Z, Furnari F, Berns M, Cleveland DW (June 2004). "Dynamics of centromere and kinetochore proteins; implications for checkpoint signaling and silencing". Current Biology. 14 (11): 942–52. Bibcode:2004CBio...14..942S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.046. PMID 15182667.

- ^ Tirnauer JS, Canman JC, Salmon ED, Mitchison TJ (December 2002). "EB1 targets to kinetochores with attached, polymerizing microtubules". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 13 (12): 4308–16. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0236. PMC 138635. PMID 12475954.

- ^ Kaplan KB, Burds AA, Swedlow JR, Bekir SS, Sorger PK, Näthke IS (April 2001). "A role for the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli protein in chromosome segregation". Nature Cell Biology. 3 (4): 429–32. doi:10.1038/35070123. PMID 11283619. S2CID 12645435.

- ^ Joseph J, Liu ST, Jablonski SA, Yen TJ, Dasso M (April 2004). "The RanGAP1-RanBP2 complex is essential for microtubule-kinetochore interactions in vivo". Current Biology. 14 (7): 611–7. Bibcode:2004CBio...14..611J. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.031. PMID 15062103.

- ^ Salina D, Enarson P, Rattner JB, Burke B (September 2003). "Nup358 integrates nuclear envelope breakdown with kinetochore assembly". The Journal of Cell Biology. 162 (6): 991–1001. doi:10.1083/jcb.200304080. PMC 2172838. PMID 12963708.

- ^ Ohta S, Bukowski-Wills JC, Sanchez-Pulido L, Alves F, Wood L, Chen ZA, et al. (September 2010). "The protein composition of mitotic chromosomes determined using multiclassifier combinatorial proteomics". Cell. 142 (5): 810–21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.047. PMC 2982257. PMID 20813266.

- ^ Tipton AR, Wang K, Oladimeji P, Sufi S, Gu Z, Liu ST (June 2012). "Identification of novel mitosis regulators through data mining with human centromere/kinetochore proteins as group queries". BMC Cell Biology. 13: 15. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-13-15. PMC 3419070. PMID 22712476.

- ^ McEwen BF, Heagle AB, Cassels GO, Buttle KF, Rieder CL (June 1997). "Kinetochore fiber maturation in PtK1 cells and its implications for the mechanisms of chromosome congression and anaphase onset". The Journal of Cell Biology. 137 (7): 1567–80. doi:10.1083/jcb.137.7.1567. PMC 2137823. PMID 9199171.

- ^ a b Nicklas RB, Kubai DF (1985). "Microtubules, chromosome movement, and reorientation after chromosomes are detached from the spindle by micromanipulation". Chromosoma. 92 (4): 313–24. doi:10.1007/BF00329815. PMID 4042772. S2CID 24739460.

- ^ Mayor T, Meraldi P, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA, Fry AM (June 1999). "Protein kinases in control of the centrosome cycle". FEBS Letters. 452 (1–2): 92–5. Bibcode:1999FEBSL.452...92M. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00534-7. PMID 10376685. S2CID 22671038.

- ^ a b Kirschner M, Mitchison T (May 1986). "Beyond self-assembly: from microtubules to morphogenesis". Cell. 45 (3): 329–42. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90318-1. PMID 3516413. S2CID 36994346.

- ^ Holy TE, Leibler S (June 1994). "Dynamic instability of microtubules as an efficient way to search in space". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (12): 5682–5. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.5682H. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.12.5682. PMC 44060. PMID 8202548.

- ^ Hayden JH, Bowser SS, Rieder CL (September 1990). "Kinetochores capture astral microtubules during chromosome attachment to the mitotic spindle: direct visualization in live newt lung cells". The Journal of Cell Biology. 111 (3): 1039–45. doi:10.1083/jcb.111.3.1039. PMC 2116290. PMID 2391359.

- ^ Nicklas RB (January 1997). "How cells get the right chromosomes". Science. 275 (5300): 632–7. doi:10.1126/science.275.5300.632. PMID 9005842. S2CID 30090031.

- ^ Loncarek J, Kisurina-Evgenieva O, Vinogradova T, Hergert P, La Terra S, Kapoor TM, Khodjakov A (November 2007). "The centromere geometry essential for keeping mitosis error free is controlled by spindle forces". Nature. 450 (7170): 745–9. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..745L. doi:10.1038/nature06344. PMC 2586812. PMID 18046416.

- ^ Dewar H, Tanaka K, Nasmyth K, Tanaka TU (March 2004). "Tension between two kinetochores suffices for their bi-orientation on the mitotic spindle". Nature. 428 (6978): 93–7. Bibcode:2004Natur.428...93D. doi:10.1038/nature02328. PMID 14961024. S2CID 4418232.

- ^ Echeverri CJ, Paschal BM, Vaughan KT, Vallee RB (February 1996). "Molecular characterization of the 50-kD subunit of dynactin reveals function for the complex in chromosome alignment and spindle organization during mitosis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 132 (4): 617–33. doi:10.1083/jcb.132.4.617. PMC 2199864. PMID 8647893.

- ^ Sharp DJ, Rogers GC, Scholey JM (December 2000). "Cytoplasmic dynein is required for poleward chromosome movement during mitosis in Drosophila embryos". Nature Cell Biology. 2 (12): 922–30. doi:10.1038/35046574. PMID 11146657. S2CID 11753626.

- ^ Banks JD, Heald R (February 2001). "Chromosome movement: dynein-out at the kinetochore". Current Biology. 11 (4): R128-31. Bibcode:2001CBio...11.R128B. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00059-8. PMID 11250166.

- ^ Howell BJ, McEwen BF, Canman JC, Hoffman DB, Farrar EM, Rieder CL, Salmon ED (December 2001). "Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin drives kinetochore protein transport to the spindle poles and has a role in mitotic spindle checkpoint inactivation". The Journal of Cell Biology. 155 (7): 1159–72. doi:10.1083/jcb.200105093. PMC 2199338. PMID 11756470.

- ^ Cooke CA, Schaar B, Yen TJ, Earnshaw WC (December 1997). "Localization of CENP-E in the fibrous corona and outer plate of mammalian kinetochores from prometaphase through anaphase". Chromosoma. 106 (7): 446–55. doi:10.1007/s004120050266. PMID 9391217. S2CID 18884489.

- ^ Weaver BA, Bonday ZQ, Putkey FR, Kops GJ, Silk AD, Cleveland DW (August 2003). "Centromere-associated protein-E is essential for the mammalian mitotic checkpoint to prevent aneuploidy due to single chromosome loss". The Journal of Cell Biology. 162 (4): 551–63. doi:10.1083/jcb.200303167. PMC 2173788. PMID 12925705.

- ^ a b Maiato H, Rieder CL, Khodjakov A (December 2004). "Kinetochore-driven formation of kinetochore fibers contributes to spindle assembly during animal mitosis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 167 (5): 831–40. doi:10.1083/jcb.200407090. PMC 2172442. PMID 15569709.

- ^ Mitchison TJ (1988). "Microtubule dynamics and kinetochore function in mitosis". Annual Review of Cell Biology. 4 (1): 527–49. doi:10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.002523. PMID 3058165.

- ^ a b c He X, Rines DR, Espelin CW, Sorger PK (July 2001). "Molecular analysis of kinetochore-microtubule attachment in budding yeast". Cell. 106 (2): 195–206. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00438-X. PMID 11511347.

- ^ a b Westermann S, Cheeseman IM, Anderson S, Yates JR, Drubin DG, Barnes G (October 2003). "Architecture of the budding yeast kinetochore reveals a conserved molecular core". The Journal of Cell Biology. 163 (2): 215–22. doi:10.1083/jcb.200305100. PMC 2173538. PMID 14581449.

- ^ a b De Wulf P, McAinsh AD, Sorger PK (December 2003). "Hierarchical assembly of the budding yeast kinetochore from multiple subcomplexes". Genes & Development. 17 (23): 2902–21. doi:10.1101/gad.1144403. PMC 289150. PMID 14633972.

- ^ Goh PY, Kilmartin JV (May 1993). "NDC10: a gene involved in chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". The Journal of Cell Biology. 121 (3): 503–12. doi:10.1083/jcb.121.3.503. PMC 2119568. PMID 8486732.

- ^ Nabetani A, Koujin T, Tsutsumi C, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y (September 2001). "A conserved protein, Nuf2, is implicated in connecting the centromere to the spindle during chromosome segregation: a link between the kinetochore function and the spindle checkpoint". Chromosoma. 110 (5): 322–34. doi:10.1007/s004120100153. PMID 11685532. S2CID 22443613.

- ^ a b Howe M, McDonald KL, Albertson DG, Meyer BJ (June 2001). "HIM-10 is required for kinetochore structure and function on Caenorhabditis elegans holocentric chromosomes". The Journal of Cell Biology. 153 (6): 1227–38. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.6.1227. PMC 2192032. PMID 11402066.

- ^ a b c Martin-Lluesma S, Stucke VM, Nigg EA (September 2002). "Role of Hec1 in spindle checkpoint signaling and kinetochore recruitment of Mad1/Mad2". Science. 297 (5590): 2267–70. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.2267M. doi:10.1126/science.1075596. PMID 12351790. S2CID 7879023.

- ^ a b c McCleland ML, Gardner RD, Kallio MJ, Daum JR, Gorbsky GJ, Burke DJ, Stukenberg PT (January 2003). "The highly conserved Ndc80 complex is required for kinetochore assembly, chromosome congression, and spindle checkpoint activity". Genes & Development. 17 (1): 101–14. doi:10.1101/gad.1040903. PMC 195965. PMID 12514103.

- ^ Zheng L, Chen Y, Lee WH (August 1999). "Hec1p, an evolutionarily conserved coiled-coil protein, modulates chromosome segregation through interaction with SMC proteins". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 19 (8): 5417–28. doi:10.1128/mcb.19.8.5417. PMC 84384. PMID 10409732.

- ^ Wei RR, Al-Bassam J, Harrison SC (January 2007). "The Ndc80/HEC1 complex is a contact point for kinetochore-microtubule attachment". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 14 (1): 54–9. doi:10.1038/nsmb1186. PMID 17195848. S2CID 5991912.

- ^ Courtwright AM, He X (November 2002). "Dam1 is the right one: phosphoregulation of kinetochore biorientation". Developmental Cell. 3 (5): 610–1. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00332-5. PMID 12431367.

- ^ a b Cimini D, Moree B, Canman JC, Salmon ED (October 2003). "Merotelic kinetochore orientation occurs frequently during early mitosis in mammalian tissue cells and error correction is achieved by two different mechanisms". Journal of Cell Science. 116 (Pt 20): 4213–25. doi:10.1242/jcs.00716. PMID 12953065.

- ^ Adams RR, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC (February 2001). "Chromosomal passengers and the (aurora) ABCs of mitosis". Trends in Cell Biology. 11 (2): 49–54. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01880-8. PMID 11166196.

- ^ Cheeseman IM, Anderson S, Jwa M, Green EM, Kang J, Yates JR, et al. (October 2002). "Phospho-regulation of kinetochore-microtubule attachments by the Aurora kinase Ipl1p". Cell. 111 (2): 163–72. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00973-X. PMID 12408861.

- ^ Gautschi O, Heighway J, Mack PC, Purnell PR, Lara PN, Gandara DR (March 2008). "Aurora kinases as anticancer drug targets". Clinical Cancer Research. 14 (6): 1639–48. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2179. PMID 18347165. S2CID 14818961.

- ^ Meraldi P, Draviam VM, Sorger PK (July 2004). "Timing and checkpoints in the regulation of mitotic progression". Developmental Cell. 7 (1): 45–60. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.006. PMID 15239953.

- ^ Tang TT, Bickel SE, Young LM, Orr-Weaver TL (December 1998). "Maintenance of sister-chromatid cohesion at the centromere by the Drosophila MEI-S332 protein". Genes & Development. 12 (24): 3843–56. doi:10.1101/gad.12.24.3843. PMC 317262. PMID 9869638.

- ^ McGuinness BE, Hirota T, Kudo NR, Peters JM, Nasmyth K (March 2005). "Shugoshin prevents dissociation of cohesin from centromeres during mitosis in vertebrate cells". PLOS Biology. 3 (3) e86. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030086. PMC 1054882. PMID 15737064.

- ^ Joseph J, Tan SH, Karpova TS, McNally JG, Dasso M (February 2002). "SUMO-1 targets RanGAP1 to kinetochores and mitotic spindles". The Journal of Cell Biology. 156 (4): 595–602. doi:10.1083/jcb.200110109. PMC 2174074. PMID 11854305.

- ^ Arnaoutov A, Dasso M (July 2003). "The Ran GTPase regulates kinetochore function". Developmental Cell. 5 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00194-1. PMID 12852855.

- ^ Prasanth SG, Prasanth KV, Siddiqui K, Spector DL, Stillman B (July 2004). "Human Orc2 localizes to centrosomes, centromeres and heterochromatin during chromosome inheritance". The EMBO Journal. 23 (13): 2651–63. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600255. PMC 449767. PMID 15215892.

- ^ Shimada K, Gasser SM (January 2007). "The origin recognition complex functions in sister-chromatid cohesion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Cell. 128 (1): 85–99. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.045. PMID 17218257.

- ^ Kato H, Matsunaga F, Miyazaki S, Yin L, D'Urso G, Tanaka K, Murakami Y (April 2008). "Schizosaccharomyces pombe Orc5 plays multiple roles in the maintenance of genome stability throughout the cell cycle". Cell Cycle. 7 (8): 1085–96. doi:10.4161/cc.7.8.5710. PMID 18414064.

- ^ Skibbens RV, Skeen VP, Salmon ED (August 1993). "Directional instability of kinetochore motility during chromosome congression and segregation in mitotic newt lung cells: a push-pull mechanism". The Journal of Cell Biology. 122 (4): 859–75. doi:10.1083/jcb.122.4.859. PMC 2119582. PMID 8349735.

- ^ Rieder CL, Salmon ED (February 1994). "Motile kinetochores and polar ejection forces dictate chromosome position on the vertebrate mitotic spindle". The Journal of Cell Biology. 124 (3): 223–33. doi:10.1083/jcb.124.3.223. PMC 2119939. PMID 8294508.

- ^ Skibbens RV, Rieder CL, Salmon ED (July 1995). "Kinetochore motility after severing between sister centromeres using laser microsurgery: evidence that kinetochore directional instability and position is regulated by tension". Journal of Cell Science. 108 ( Pt 7) (7): 2537–48. doi:10.1242/jcs.108.7.2537. PMID 7593295.

- ^ Askham JM, Vaughan KT, Goodson HV, Morrison EE (October 2002). "Evidence that an interaction between EB1 and p150(Glued) is required for the formation and maintenance of a radial microtubule array anchored at the centrosome". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 13 (10): 3627–45. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0061. PMC 129971. PMID 12388762.

- ^ Schuyler SC, Pellman D (May 2001). "Microtubule "plus-end-tracking proteins": The end is just the beginning". Cell. 105 (4): 421–4. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00364-6. PMID 11371339.

- ^ Howard J, Hyman AA (April 2003). "Dynamics and mechanics of the microtubule plus end". Nature. 422 (6933): 753–8. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..753H. doi:10.1038/nature01600. PMID 12700769. S2CID 4427406.

- ^ Green RA, Wollman R, Kaplan KB (October 2005). "APC and EB1 function together in mitosis to regulate spindle dynamics and chromosome alignment". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 16 (10): 4609–22. doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0259. PMC 1237068. PMID 16030254.

- ^ Dujardin D, Wacker UI, Moreau A, Schroer TA, Rickard JE, De Mey JR (May 1998). "Evidence for a role of CLIP-170 in the establishment of metaphase chromosome alignment". The Journal of Cell Biology. 141 (4): 849–62. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.4.849. PMC 2132766. PMID 9585405.

- ^ Maiato H, Khodjakov A, Rieder CL (January 2005). "Drosophila CLASP is required for the incorporation of microtubule subunits into fluxing kinetochore fibres". Nature Cell Biology. 7 (1): 42–7. doi:10.1038/ncb1207. PMC 2596653. PMID 15592460.

- ^ Maiato H, Fairley EA, Rieder CL, Swedlow JR, Sunkel CE, Earnshaw WC (June 2003). "Human CLASP1 is an outer kinetochore component that regulates spindle microtubule dynamics". Cell. 113 (7): 891–904. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00465-3. hdl:10216/53832. PMID 12837247. S2CID 13936836.

External links

[edit]- Kinetochores at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)