Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lippe (district)

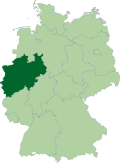

View on WikipediaLippe (German pronunciation: [ˈlɪpə]) is a Kreis (district) in the east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Neighboring districts are Herford, Minden-Lübbecke, Höxter, Paderborn, Gütersloh, and district-free Bielefeld, which forms the region Ostwestfalen-Lippe.

Key Information

The district of Lippe is named after the Lords of Lippe, who originally lived on the river Lippe and founded Lippstadt there, and their Principality of Lippe. It was a state within the Holy Roman Empire and retained statehood until 1947, when it became a district of North Rhine-Westphalia.

History

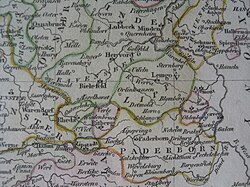

[edit]The Lippe district nearly covers the same area as the historic County of Lippe. The first mention of this country was in 1123; it grew in power slowly in the following centuries. In 1528 it became a county, in 1789 it was elevated to a principality.

Unlike many other countries of the Holy Roman Empire in the area, Lippe kept its independence in the Napoleonic era, and thus wasn't incorporated into Prussia afterwards. It was one of the smaller member states of the German empire.

After the death of Prince Woldemar in 1895, the two lines of the House of Lippe fought over the regency for over a decade.

The last prince of Lippe was forced to abdicate during the November Revolution of 1918 following the Collapse of the Imperial German Army, whilst Germany as a whole became the Weimar Republic. The district became a Freistaat one of the constituent parts of the new republic. In 1932 the Free State of Lippe was subdivided into two districts, Detmold and Lemgo. These continued to exist when in 1947 Lippe lost its status as a state of Germany and by order of the British military government was incorporated into the new federal state North Rhine-Westphalia; in 1949 this change was approved by the parliament. In 1969/70 the 168 cities and municipalities were merged to 16; and as the second part of the administrative reform in 1973 the two districts Lemgo and Detmold were merged to the district Lippe.

Geography

[edit]The Lippe district covers the northern part of the Teutoburg Forest, which also contain the highest elevation of the district, the 496 meter high Köterberg near Lügde. The lowest elevation is at the Weser river with 45.5 m. The main river is the Werre, and at the northern border of the district the Weser. The Lippe River, which shares the district's name, does not flow through Lippe, but has its headwaters right across the district line in Bad Lippspringe, Kreis Paderborn. The small territories of Lippstadt, Lipperode, and Cappel that belonged to Lippe until the mid 19th century, do lie in the valley of the river.

Coat of arms

[edit]The coat of arms shows the traditional symbol of the state of Lippe, the rose, as the district covers nearly the same area as the historic country. In the middle of the rose 16 stamens symbolize the 16 cities and municipalities of the district. The coat of arms was granted in 1973.

Despite the relatively small size of Lippe, the Lippish rose is also one of only three symbols included in the coat of arms of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Towns and municipalities

[edit]

| Towns | Municipalities |

|---|---|

Culinary art

[edit]The most famous dish served in Lippe is the pickert. In the past it was known as a meal for poor people. The main ingredients are potatoes, flour and raisins.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]External links

[edit]- Official website Archived 2013-07-18 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- Ordinances and by-laws of the county of Lippe online

- Guidelines for the integration of the Land Lippe within the territory of the federal state North-Rhine-Westphalia of 17 January 1947

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Religious history of Lippe from the Reformation until the early twentieth century

Lippe (district)

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Medieval Development

The Lordship of Lippe emerged in 1123, when Bernard I (c. 1090–c. 1158) was first recorded as its lord, having received a grant of territory from Holy Roman Emperor Lothar III near the Lippe River, initially centered around areas west of Paderborn that included early settlements and riverine holdings.[6] This foundational domain, spanning roughly the middle Weser region and southeastern Teutoburg Forest fringes, served as a buffer amid competing Saxon nobilities, with Bernard establishing the family's administrative base through feudal vassalage and monastic foundations like Obernkirchen Abbey for economic consolidation.[6] Under subsequent lords, the territory expanded incrementally via marriages, purchases, and conquests, transitioning from scattered lordships to a more cohesive county by the late medieval period. Hermann I (d. 1167) and his successors fortified key sites, including early castles at Lippspringe and along trade routes, while Bernard II (c. 1140–1196) further delineated holdings through imperial privileges. A pivotal acquisition occurred in 1247 when Otto I (r. 1246–1260) married the heiress of Schwalenberg County, incorporating its southeastern lands and extending Lippe's influence northward to the Weser by the 14th century, amid regional conflicts with archbishoprics like Paderborn.[6] The medieval consolidation faced religious upheaval in the 16th century under Simon V (1471–1536), who assumed the comital title in 1528 and sought to maintain Catholic dominance amid the Reformation's spread. Simon V employed coercive measures to curb Protestant preaching and conversions in Lippe's towns and rural estates, viewing them as threats to feudal authority and imperial allegiance, though these efforts faltered due to local sympathies and external pressures from reformers in neighboring Hesse.[7] Following his death, his son Bernhard VIII (r. 1536–1563) relented, promulgating Lippe's first Protestant church ordinance in 1538, marking the lordship's shift to Lutheranism despite Simon's resistance.[7]Principality of Lippe and Early Modern Period

In 1720, the County of Lippe-Detmold was elevated to the status of a principality by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, granting the ruler Friedrich Adolf the title of prince and enhancing its sovereignty within the Empire.[6] This elevation reflected the consolidation of Lippe's territorial holdings under the Detmold line following earlier partitions, positioning it as a mediatized imperial estate with voting rights in the Imperial Diet.[6] Following the Napoleonic Wars, the Principality of Lippe joined the German Confederation in 1815 as one of its 39 sovereign states, maintaining internal autonomy while participating in collective defense and foreign policy coordinated through the Confederation's diet in Frankfurt.[8] During the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Lippe aligned with Prussia against Austria, providing a contingent of troops to the Prussian army, which contributed to the decisive Prussian victory at Königgrätz and the dissolution of the Confederation.[6] This strategic choice, driven by geographic proximity and the need for protection against larger powers, led to Lippe's incorporation into the Prussian-dominated North German Confederation in 1867.[6] Governance under the princely house remained hereditary and largely absolute, with rulers exercising executive authority supported by a state council and periodic assemblies of estates, though reforms in the 1840s introduced limited constitutional elements amid revolutionary pressures.[9] A significant internal challenge arose in 1905 upon the death of the mentally incapacitated Prince Alexander, sparking a succession dispute among branches of the House of Lippe, including claims from Lippe-Biesterfeld, Lippe-Weissenfeld, and Schaumburg-Lippe.[10] The conflict, rooted in interpretations of house laws and morganatic marriages, was resolved through judicial arbitration favoring the Lippe-Biesterfeld line, enabling Leopold IV to ascend as prince and rule until his abdication on November 12, 1918, amid the collapse of German monarchies.[9][11]19th and 20th Century Integration

Following the abdication of Prince Leopold IV on November 12, 1918, amid the German Revolution, the Principality of Lippe transitioned to the Free State of Lippe, marking the end of monarchical rule and the adoption of a republican framework within the Weimar Republic.[12][6] This shift dissolved the princely house's direct governance while preserving Lippe's status as an independent state, with Detmold continuing as its capital.[6] During the subsequent Nazi regime from 1933 onward, the Free State's democratic institutions were suppressed, aligning it with national policies until the regime's collapse in 1945.[13] Post-World War II, under British military administration in the occupation zone, Lippe's state government was temporarily restored under Social Democratic leadership, reflecting pre-Nazi governance patterns.[6] However, on January 21, 1947, British authorities mandated its merger into the newly formed state of North Rhine-Westphalia, abolishing Lippe's separate sovereignty to streamline regional administration amid Allied reorganization efforts.[6][14] This integration involved minimal boundary alterations, with the resulting Lippe district retaining core historical contours north and south of the Weser River, extending to the Teutoburg Forest, thus avoiding major territorial losses or gains compared to pre-war delineations.[14][15] To safeguard Lippe's cultural and historical identity post-merger, the Landesverband Lippe was established by state law effective October 12, 1949, functioning as a regional association for preserving local traditions, archives, and communal ties without administrative authority.[16] The 1947 incorporation coincided with broader population shifts in western Germany, including resettlement of expellees from eastern territories, though Lippe experienced relatively contained demographic pressures due to its inland position and stable borders, with no documented large-scale expulsions from its own area.[15] This framework allowed Lippe to function as a district while maintaining distinct regional consciousness within North Rhine-Westphalia's federal structure.Geography and Environment

Location and Boundaries

The Lippe district occupies a position in the eastern expanse of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, falling under the administrative oversight of the Detmold governmental district. It abuts the state of Lower Saxony along its northern and eastern peripheries, specifically interfacing with the districts of Schaumburg, Hameln-Pyrmont, and Holzminden, while connecting to fellow North Rhine-Westphalian districts including Minden-Lübbecke and Herford to the northwest, Gütersloh to the southwest, Paderborn to the south, and Höxter to the southeast.[17] Spanning 1,246.22 square kilometers, the district's terrain incorporates the northern reaches of the Teutoburg Forest and aligns its eastern limit with the Weser River, which marks the transition to Lower Saxony at elevations as low as 45.5 meters above sea level.[18][2] The district's boundaries achieved their contemporary configuration upon integration into North Rhine-Westphalia on January 21, 1947, subsequent to the dissolution of the Free State of Lippe, and have exhibited stability without substantive alterations thereafter.[19]Physical Features and Land Use

The Lippe district encompasses a landscape dominated by the northern reaches of the Teutoburg Forest, forming a hilly terrain with elevations averaging 169 meters above sea level and ranging from low river valleys around 100 meters to higher forested ridges exceeding 400 meters. This topography includes undulating hills, narrow valleys carved by tributaries of the Lippe River, and escarpments typical of the Weser Hills' western extension, fostering a mix of wooded uplands and open plateaus suited to mixed land uses. The Teutoburg Forest's low mountain character influences much of the district's relief, with soil profiles often featuring loess-derived loams in valley bottoms that enhance agricultural viability through good drainage and fertility.[20][21] The Lippe River constitutes the primary hydrological axis, meandering through the district for significant stretches and shaping floodplain valleys that concentrate settlement patterns and facilitate water-dependent activities. Tributaries and associated wetlands contribute to a network of streams supporting local drainage, though historical channelization for flood control has altered natural meanders in some sectors. These features create a hydrology oriented toward lowland retention in valleys amid upland percolation, with groundwater influenced by permeable sandy and gravelly substrates in forested zones.[22] Land use reflects the terrain's adaptability, with the district's total area of 1,246 km² allocated as follows: vegetation (encompassing agriculture and forests) at 81.7%, settlements at 17.5%, transportation infrastructure at 5.2%, and water surfaces at 0.8%. Agricultural utilization prevails, covering approximately 545 km² of operational farmland as of 2020, primarily arable fields (around 440 km²) on valley loams and grasslands (about 95 km²), underscoring the region's farming orientation. Woodlands, concentrated in Teutoburg extensions, comprise roughly 13% natural forest cover (156 km² in 2020), utilized for timber and recreation, while built-up areas cluster along river corridors to minimize upland disruption.[18][23][24]Climate and Natural Resources

The Lippe district, situated in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, exhibits a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb) with moderate seasonal variations, influenced by its inland position and proximity to the Teutoburg Forest. In Detmold, the district's administrative center, the average annual temperature is approximately 9.5°C, with July highs averaging 22°C and January lows around 0°C, occasionally dipping below -5°C during cold spells. Winters are cool and overcast, while summers remain mild, rarely exceeding 30°C, supporting a growing season from April to October conducive to temperate agriculture such as grain and potato cultivation.[25] Annual precipitation totals about 927 mm, evenly distributed but with summer peaks, particularly in June (around 80 mm), leading to reliable soil moisture for forestry and farming without extreme droughts or floods in most years. Relative humidity averages 80-85%, and annual sunshine hours number roughly 1,600, fostering conditions for mixed woodland growth but limiting Mediterranean-style crops. These patterns align with broader North Rhine-Westphalia trends, where empirical station data from the German Weather Service confirm consistent mildness, though microclimatic variations occur in elevated Teutoburg areas with slightly cooler temperatures and higher rainfall. Natural resources center on renewable assets, including timber from extensive woodlands covering approximately 25-30% of the district's 1,190 km² area, concentrated in the northern Teutoburg Forest and Egge Hills. These forests, dominated by beech, oak, and spruce, yield sustainable wood harvests estimated at regional levels supporting NRW's 915,800 hectares of forested land statewide, with private ownership comprising 67%. Groundwater resources derive from permeable aquifers recharged by local rivers like the Werre (a 72 km tributary of the Weser traversing the district) and smaller streams, providing potable water yields of several million cubic meters annually without significant depletion, as monitored by state hydrological surveys. Limited non-renewable minerals, such as sand and gravel aggregates, occur in river valleys, but extraction remains minor compared to forestry and hydrological assets.[26]Administration and Government

Coat of Arms and Heraldry

The coat of arms of Lippe district features a red five-petaled rose with a golden center and golden sepals on a silver field, as specified in § 2 of the district's Hauptsatzung.[27] This design, known as the Lippische Rose, serves as the official emblem for administrative acts and symbolizes the district's historical identity derived from the medieval Lords of Lippe.[28] The Lippische Rose traces its origins to the early 13th century, with the earliest attestation in a 1208 seal of the Lords of Lippe, reflecting knightly heraldry practices of the high medieval period.[29] Associated with Bernhard II zur Lippe (late 12th century), who founded settlements like Lippstadt and Lemgo, the rose initially appeared with yellow petals and a red center before evolving to its current red-petaled form with golden accents by the post-1600 period.[29] It continued as a central element in the arms of the Principality of Lippe until 1918, maintaining continuity with the region's sovereign past.[28] Following the 1973 municipal reform that restructured the district, the coat of arms was officially approved on July 17, 1973, by North Rhine-Westphalian authorities, incorporating the traditional Lippische Rose to represent the unified 16 municipalities (10 cities and 6 communes). In heraldic terms, the blazon is "In Silber eine rote fünfblättrige Rose mit goldenem Butzen und goldenen Kelchblättern," adhering to standard German tinctures of argent, gules, and or.[27] The emblem appears in official seals, flags, and documents, and is integrated into the North Rhine-Westphalia state arms, underscoring its role in denoting regional authority without alteration for non-official uses.[28]Administrative Structure

The Lippe district encompasses 16 independent municipalities responsible for local governance, including urban planning, education, and public utilities, under the coordinating authority of the district administration (Kreisverwaltung) based in Detmold.[30] This structure reflects the two-tier system typical of rural districts (Kreise) in North Rhine-Westphalia, where municipalities retain autonomy while the district handles regional tasks such as waste management, road maintenance, and hospital provision.[18] The municipalities comprise ten towns (Städte) and six rural municipalities (Gemeinden), as established following the territorial reforms of 1969–1975 that merged over 160 smaller entities into the current configuration to streamline administration and reduce costs.[30] The towns are: Bad Salzuflen, Barntrup, Blomberg, Detmold, Horn-Bad Meinberg, Lage, Lemgo, Lügde, Oerlinghausen, and Schieder-Schwalenberg.[18] The rural municipalities are: Augustdorf, Dörentrup, Extertal, Kalletal, Leopoldshöhe, and Schlangen.[18] Detmold functions as the administrative seat, hosting the district's executive offices and serving as the primary hub for inter-municipal coordination via the district council (Kreistag), which elects the district administrator (Landrat) to oversee district-level policies.[30] No intermediate administrative subdivisions, such as former Ämter, exist post-reform, ensuring direct district-municipality relations.[18]Local Politics and Governance

The Landrat of Lippe district, serving as the chief executive, is elected directly by voters every five years during North Rhine-Westphalia's communal elections. In the September 14, 2025, first round, no candidate secured an absolute majority, prompting a runoff on September 28, 2025, where Christian Democratic Union (CDU) candidate Meinolf Haase prevailed with 55.61% of valid votes against Social Democratic Party (SPD) challenger Ilka Kottmann's 44.39%.[31] [32] Haase, previously a municipal politician from Lügde, succeeds SPD incumbent Axel Lehmann, who held the office since 2015.[33] The Kreistag, Lippe's district council with 66 seats, functions as the primary legislative assembly, elected concurrently to represent diverse voter alignments. The 2025 elections yielded a CDU plurality, with the party capturing the largest share of seats amid gains from the prior cycle, followed by the SPD and Greens; this composition underscores persistent conservative voter majorities in the predominantly rural electorate, where turnout reached approximately 50%.[34] [35] The council oversees budgetary approvals, policy frameworks, and oversight of the Landrat, convening regularly to address district-specific mandates. Contemporary priorities encompass bolstering infrastructure, including broadband expansion and road maintenance to mitigate rural isolation, alongside sustaining services like emergency medical response and school transport.[36] These efforts align with empirical needs in a district spanning 1,195 square kilometers of dispersed settlements, where population density averages 220 per square kilometer. Governance interfaces with the North Rhine-Westphalia state administration via coordinated funding for regional projects, such as those under the state's rural development programs, ensuring alignment with provincial fiscal and regulatory directives.[37]Demographics

Population Trends

The population of Lippe district was recorded at 347,149 inhabitants as of December 2023, reflecting a relatively stable trajectory with minor annual fluctuations over the preceding decade.[18][38] Official statistics indicate a peak of 349,069 in 2017, followed by a slight decline to 346,151 by the end of 2021, before a modest rebound.[39] This pattern aligns with broader regional trends in rural North Rhine-Westphalia, where natural decrease from low birth rates has been partially offset by net migration.[40]| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 348,441 |

| 2017 | 349,069 |

| 2021 | 346,151 |

| 2023 | 347,149 |

Ethnic and Social Composition

The population of Lippe district remains predominantly ethnic German, reflecting historical homogeneity reinforced by the integration of post-World War II expellees (Vertriebene) from former eastern German territories and Polish areas, who numbered nearly 10,000 in Detmold alone by the 1950 census and assimilated over generations into the local fabric.[44] These resettlements, driven by wartime displacements, contributed to a culturally cohesive society without altering the core German ethnic majority, as subsequent intermarriage and naturalization homogenized descendants.[45] As of December 31, 2023, foreign nationals comprised 40,600 individuals, or approximately 11.6% of the district's 347,149 residents, a figure below the North Rhine-Westphalia statewide average of over 17%.[46][18][47] The immigrant population draws primarily from EU countries (e.g., Poland with 2,365, Romania with 2,325, Bulgaria with 1,895) and non-EU origins like Turkey and Syria, with modest annual growth of about 200 persons.[48][49] Broader migration background—including naturalized citizens and their offspring—affects roughly one in four residents, encompassing both contemporary inflows and historical patterns like the Vertriebene era.[50] Socially, Lippe features stable, family-centered structures typical of rural Westphalia, with 18.5% of the population under 18 years old, indicative of ongoing nuclear family prevalence amid an aging demographic.[51] Educational attainment aligns with regional norms, bolstered by institutions like the Detmold University of Applied Sciences, though non-German residents exhibit lower average qualification levels compared to natives per local integration analyses.[52] This composition supports a middle-class, community-oriented society with limited ethnic enclaves, prioritizing empirical integration metrics over narrative assumptions.[53]Economy

Industrial and Commercial Sectors

The industrial sector in Lippe district is characterized by a strong presence of small and medium-sized enterprises (Mittelstand), which dominate the approximately 1,500 manufacturing firms employing around 35,000 workers, representing nearly 30% of all socially insured employees in the region.[54] These companies generated a combined turnover of 7.5 billion euros in 2024, with key strengths in electrical engineering, plastics processing, and wood-based industries, including furniture production.[55][56] Export-oriented operations are prevalent, supported by the district's integration into the Ostwestfalen-Lippe (OWL) economic cluster, known for innovation in mechanical engineering and automation technologies.[57] Furniture manufacturing stands out, particularly in Detmold, where the sector benefits from historical expertise and contributes significantly to OWL's national leadership, accounting for over two-thirds of Germany's kitchen furniture output.[58][59] Local firms focus on high-quality wood processing and custom production, leveraging proximity to research institutions in the broader OWL region for product development in sustainable materials and design. Mechanical engineering complements this, with firms specializing in components for e-mobility and automation, positioning Lippe among top German regions for these subsectors according to a 2025 analysis by the Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft.[57] Unemployment remains relatively low, with an annual average rate around 5% in recent years, reflecting robust demand for skilled labor in these sectors despite cyclical downturns in electrical engineering subcomponents.[60][61] While textiles play a minor role compared to neighboring areas, the overall commercial landscape emphasizes resilient, specialized manufacturing tied to regional supply chains and university collaborations for R&D in materials science and engineering.[55]Agriculture, Forestry, and Rural Economy

The agricultural sector in Lippe district encompasses approximately 54,487 hectares of utilized land as of 2020, representing a significant portion of the region's land use dedicated to primary production. Of this, around 44,000 hectares are arable land, primarily cultivated for cereals such as wheat and barley, which cover about 29,000 hectares, alongside specialty crops like sugar beets on 2,800 hectares—accounting for a notable share of regional beet production. Permanent grassland spans roughly 9,518 hectares, supporting mixed farming practices that integrate crop rotation with fodder production for livestock. Livestock rearing, including cattle and pigs, predominates in grassland areas, though specific herd sizes reflect broader North Rhine-Westphalia trends of intensive animal husbandry adapted to local soil and topography.[23][23][62] Forestry contributes substantially to the rural economy, with woodlands covering about 30% of the district's approximately 119,000 hectares total area, or roughly 35,000–40,000 hectares overall. The Landesverband Lippe manages around 15,700 hectares—equivalent to 40% of the district's forests—focusing on sustainable timber yields from dominant species like beech (comprising up to 40% of tree cover) and spruce, while providing ecosystem services such as groundwater protection and carbon sequestration. Annual wood production emphasizes long-term regeneration, with reforestation efforts countering losses from pests and storms, though exact volumetric outputs vary by management zones in the Teutoburger Wald and Lippisches Bergland.[63][64][65] The rural economy relies on these sectors for employment, though mechanization has reduced labor needs, with full-time agricultural workers forming a small fraction of the district's workforce—estimated at under 2% based on regional Ostwestfalen-Lippe patterns. Seasonal labor, often for harvesting sugar beets and cereals, faces challenges including low effective wages after deductions for housing and transport, prompting calls for improved conditions amid reliance on migrant workers. Traditional efficiencies in land use persist, with over 50% of Ostwestfalen-Lippe's area agriculturally productive, but structural shifts toward larger farms have consolidated operations, limiting smallholder viability while sustaining output through scale.[66][67]Recent Economic Developments

The Smart Country Side initiative, launched in 2016 within the Ostwestfalen-Lippe region including Lippe district, has promoted digital solutions for rural challenges such as aging populations and limited services, involving collaborations between municipalities in Lippe and neighboring Höxter to enhance connectivity and local innovation.[68] Funded partly by EU ERDF programs, the project has tested applications like remote health monitoring and smart mobility, aiming to retain residents amid outmigration pressures by improving rural livability without over-dependence on urban migration.[69] Outcomes include pilot implementations in Lippe villages, though scalability remains constrained by uneven broadband rollout and reliance on public subsidies, which constitute a notable portion of regional development funding.[4] Digital infrastructure expansions, aligned with the Lippe 2025 Future Concept adopted in 2017, have prioritized high-speed internet and open government data to foster economic dynamism and counteract youth outmigration, with the district targeting leadership in rural digitalization by enhancing remote work viability and startup ecosystems.[70] Complementing this, the Technische Hochschule Ostwestfalen-Lippe (TH OWL) in Detmold underwent campus expansions, including the 2024 student-led designs for the Kreativcampus extension to support interdisciplinary programs in media, informatics, and design, bolstering skilled labor retention.[71] Additionally, the 2018 partnership between Bielefeld University and Klinikum Lippe established a university clinic, investing in medical training and research facilities to attract professionals and integrate health innovation into the local economy.[72] Economic growth in Lippe has mirrored Ostwestfalen-Lippe's robust performance, with gross domestic product per capita rising 34.8% from 2012 to 2022—outpacing other North Rhine-Westphalia regions—driven by resilient medium-sized enterprises in manufacturing and engineering sectors.[73] The IHK Lippe business climate index improved to 94 points in spring 2025 from 90 in autumn 2024, reflecting optimism among SMEs despite national headwinds like energy costs, though industrial turnover dipped to 7.57 billion euros in 2024 amid supply chain disruptions.[74] This resilience stems from family-owned firms' adaptability, with gross value added growth exceeding state averages, but sustained progress requires reducing subsidy dependence to mitigate vulnerability to policy shifts.[75] Underemployment edged up to 17,256 persons in January 2025, signaling mild labor market softening yet underscoring the need for diversified job creation beyond traditional industries.[76]Culture and Heritage

Culinary Traditions

The culinary traditions of Lippe emphasize hearty, preservation-oriented dishes derived from its agrarian economy, which historically relied on potatoes, grains, livestock, and foraged berries for sustenance in a rural setting. Central to this is the Pickert, a dense, yeast-leavened potato flatbread made by grating raw potatoes, mixing with flour, buttermilk, and sometimes buckwheat, then baking or frying it into thick pancakes; originally a staple for laborers due to its use of abundant, inexpensive tubers, it was consumed weekly in many households as a versatile base for sweet or savory toppings like liver sausage, jam, or curd cheese. This dish's simplicity and nutritional density—providing sustained energy from local harvests—underscore causal links to Lippe's potato-centric farming, with production peaking in autumn after harvests.[77][78] Smoked meats, particularly Westfälischer Knochenschinken (Westphalian bone-in ham), represent another pillar, produced by salting pork legs from regional swine breeds, cold-smoking them over beech wood for 2-3 weeks, and air-drying for up to a year while retaining the bone for flavor infusion; this method, yielding a robust, aromatic cure, earned EU Protected Geographical Indication status in 2013, restricting production to Westphalia—including Lippe—where beech forests and traditional smokehouses provide the requisite conditions. Lippischer variants adapt similar techniques, often featured in communal feasts. Complementing these are rye-based breads like dense, sourdough Roggenbrot or pumpernickel-style loaves, baked from coarse local grains to yield long-lasting staples that pair with hams and cheeses, reflecting grain surpluses from Lippe's fertile soils.[79][80] Seasonal practices tie cuisine to agriculture through events like Schlachtefest (slaughter festivals), held in late autumn across Lippe's villages since medieval times, where families process pigs into sausages, blood puddings, and preserved cuts using on-site kills to minimize waste and maximize winter storage via smoking or potting; these gatherings, documented in regional cookbooks, foster social bonds while utilizing breed-specific fats and meats. Heritage poultry such as the Lippe Goose, a white-feathered grazing breed documented in Westphalia since circa 1860 and raised on pasture for tender, flavorful meat, features in holiday roasts. Beverages include fruit-based distillates like pear brandy (Williamsbirnenbrand) or sloe spirit (Schlehengeist), distilled from wild or orchard fruits in small-scale operations, alongside juniper-infused Wacholder spirits that echo foraging traditions. Markets and bike tours promote these items, ensuring continuity from farm to table without industrial dilution.[81][82][83]Cultural Institutions and Landmarks

The Schloss Detmold, a Baroque residence built between 1699 and 1704 for the princely house of Lippe, serves as a central cultural landmark in the district's capital, housing collections related to regional nobility and history.[84] Adjacent to the castle, the Lippisches Landesmuseum, established in 1835 and the largest and oldest museum in Ostwestfalen-Lippe, preserves artifacts spanning archaeology, natural history, regional art from the Baroque era, and everyday items like furniture and toys from Lippe's past.[85][86] The Hermannsdenkmal, a 53.5-meter-high monument erected between 1838 and 1875 by sculptor Ernst von Bandel on the Grotenburg hill near Detmold-Hiddesen, commemorates Arminius's victory over Roman forces in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, symbolizing Germanic resistance and standing as Germany's largest enclosed sculpture.[87][88] The LWL-Freilichtmuseum Detmold, opened in 1960 and covering 100 hectares, exhibits over 100 relocated historical buildings from the region, including half-timbered farmhouses, workshops, and gardens furnished to reflect 18th- to 19th-century rural life, with demonstrations of traditional crafts.[89] Cultural institutions include the Grabbe-Haus theater in Detmold, hosting performances since the 19th century, and the Detmolder Sommertheater, an open-air venue operational since 1896 that stages operas and plays during summer months.[90][91] The Hochschule für Musik Detmold, founded in 1946, contributes through concerts and educational programs in classical music, fostering regional artistic development.[90]Regional Identity and Traditions

The Landesverband Lippe serves as a key institution in sustaining the district's distinct regional identity, linking the historical sovereignty of the former Principality of Lippe to modern cultural preservation efforts. Founded post-World War II amid territorial rescaling, it coordinates initiatives that emphasize Lippe's unique heritage against the backdrop of integration into North Rhine-Westphalia, including advocacy for local symbols and historical continuity in identity politics.[92] Local dialects and folklore reinforce this identity, with Lippisch Platt—a variant of Low German—embodying everyday cultural expression and historical narratives. Documented as a sub-dialect within Westphalian Low German, it features in folklore traditions like puppetry performances, where figures such as the Hermännchen character deliver dialogues in Lippisch to promote linguistic heritage among younger audiences.[93][94] Schützenfeste exemplify enduring communal traditions, with these shooting festivals held annually across Lippe's municipalities, involving marksmanship contests, parades in historical uniforms, and social rituals that foster volunteer-driven cohesion. Originating from medieval defensive practices, they persist as vital expressions of Heimat attachment, drawing thousands and requiring extensive local organization, as seen in events like the Oerlinghausen Schützenfest in July 2025.[95][96] Regional attachment remains empirically robust, with surveys highlighting stronger identification with sub-state entities like Lippe or Ostwestfalen-Lippe over North Rhine-Westphalia as a whole; for instance, a 2022 poll in the broader Ostwestfalen-Lippe area revealed high resident valuation of local Lebensqualität factors such as community ties. Yet, urbanization trends contribute to dialect decline and event participation challenges, prompting associations to counter potential assimilation through targeted revival programs.[97][93]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kreiswappen_des_Kreises_Lippe.png