Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

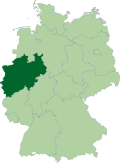

Bonn (German pronunciation: [bɔn] ⓘ) is a federal city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located on the banks of the Rhine. With a population exceeding 300,000, it lies about 24 km (15 mi) south-southeast of Cologne, in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region.

Key Information

Bonn served as the capital of West Germany from 1949 until 1990 and was the seat of government for reunified Germany until 1999, when the government relocated to Berlin. The city holds historical significance as the birthplace of Germany's current constitution, the Basic Law.

Founded in the 1st century BC as a settlement of the Ubii and later part of the Roman province Germania Inferior, Bonn is among Germany's oldest cities. It was the capital city of the Electorate of Cologne from 1597 to 1794 and served as the residence of the Archbishops and Prince-electors of Cologne. The period during which Bonn was the capital of West Germany is often referred to by historians as the Bonn Republic.[2]

Following the German reunification, a political compromise known as the Berlin-Bonn Act ensured that the German federal government retained a significant presence in Bonn. As of 2019, approximately one-third of all ministerial jobs remain in the city.[3] Bonn is considered an unofficial secondary capital of Germany and is the location of the secondary seats of the president, the chancellor, and the Bundesrat. Bonn is also the location of the primary seats of six federal ministries and twenty federal authorities. The city's title as Federal City (German: Bundesstadt) underscores its political importance.[4]

The global headquarters of Deutsche Post DHL and Deutsche Telekom, both DAX-listed corporations, are in Bonn. The city is home to the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn university, and a total of 20 United Nations institutions, the highest number in all of Germany.[5] These institutions include the headquarters for Secretariat of the UN Framework Convention Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Secretariat of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), and the UN Volunteers programme.[6] Birthplace of composer Ludwig van Beethoven, a center of Rhenish carnival, and its geography by the Middle Rhine make it an important tourist destination. In Bonn the Bönnsch Platt, a dialect of the Ripuarian language is spoken by all generations, especially during carnival.

Geography

[edit]Topography

[edit]Situated in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region, Germany's largest metropolitan area with over 11 million inhabitants, Bonn lies within the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, on the border with Rhineland-Palatinate. Spanning an area of more 141.2 km2 (55 sq mi) on both sides of the river Rhine, almost three-quarters of the city lies on the river's left bank.

To the south and to the west, Bonn borders the Eifel region which encompasses the Rhineland Nature Park. To the north, Bonn borders the Cologne Lowland. Natural borders are constituted by the river Sieg to the north-east and by the Siebengebirge (also known as the Seven Hills) to the east. The largest extension of the city in north–south dimensions is 15 km (9 mi) and 12.5 km (8 mi) in west–east dimensions. The city borders have a total length of 61 km (38 mi). The geographical centre of Bonn is the Bundeskanzlerplatz (Chancellor Square) in Bonn-Gronau.

Administration

[edit]The German state of North Rhine-Westphalia is divided into five governmental districts (German: Regierungsbezirk), and Bonn is part of the governmental district of Cologne (German: Regierungsbezirk Köln). Within this governmental district, the city of Bonn is an urban district in its own right. The urban district of Bonn is then again divided into four administrative municipal districts (German: Stadtbezirk). These are Bonn, Bonn-Bad Godesberg, Bonn-Beuel and Bonn-Hardtberg. In 1969, the independent towns of Bad Godesberg and Beuel as well as several villages were incorporated into Bonn, resulting in a city more than twice as large as before.

| Municipal district (Stadtbezirk) | Coat of arms | Population (as of December 2014[update])[7] | Sub-district (Stadtteil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bad Godesberg | 73,172 | Alt-Godesberg, Friesdorf, Godesberg-Nord, Godesberg-Villenviertel, Heiderhof, Hochkreuz, Lannesdorf, Mehlem, Muffendorf, Pennenfeld, Plittersdorf, Rüngsdorf, Schweinheim | |

| Beuel | 66,695 | Beuel-Mitte, Beuel-Ost, Geislar, Hoholz, Holtorf, Holzlar, Küdinghoven, Limperich, Oberkassel, Pützchen/Bechlinghoven, Ramersdorf, Schwarzrheindorf/Vilich-Rheindorf, Vilich, Vilich-Müldorf | |

| Bonn | 149,733 | Auerberg, Bonn-Castell (known until 2003 as Bonn-Nord), Bonn-Zentrum, Buschdorf, Dottendorf, Dransdorf, Endenich, Graurheindorf, Gronau, Ippendorf, Kessenich, Lessenich/Meßdorf, Nordstadt, Poppelsdorf, Röttgen, Südstadt, Tannenbusch, Ückesdorf, Venusberg, Weststadt | |

| Hardtberg | 33,360 | Brüser Berg, Duisdorf, Hardthöhe, Lengsdorf |

Climate

[edit]Bonn has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb; Trewartha: Dobk).[8] In the south of the Cologne lowland in the Rhine valley, Bonn is in one of Germany's warmest regions.

The Bonn weather station has recorded the following extreme values:[8]

- Its highest temperature was 40.9 °C (105.6 °F) on 25 July 2019.

- Its lowest temperature was −23.0 °C (−9.4 °F) on 27 January 1942.

- Its greatest annual precipitation was 956.7 mm (37.67 in) in 2007.

- Its least annual precipitation was 381.5 mm (15.02 in) in 1959.

- The longest annual sunshine was 2013.9 hours in 2018.

- The shortest annual sunshine was 1240.7 hours in 1981.

| Climate data for Bonn (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1933–present[a]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.9 (91.2) |

37.9 (100.2) |

40.9 (105.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

34.6 (94.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

40.9 (105.6) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.3 (90.1) |

27.4 (81.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

34.9 (94.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

0.4 (32.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −7.5 (18.5) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.0 (−9.4) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 60.1 (2.37) |

48.4 (1.91) |

51.5 (2.03) |

43.5 (1.71) |

70.1 (2.76) |

81.5 (3.21) |

83.9 (3.30) |

87.3 (3.44) |

62.5 (2.46) |

60.3 (2.37) |

60.5 (2.38) |

57.6 (2.27) |

767.1 (30.20) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 4.3 (1.7) |

2.8 (1.1) |

2.5 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 (0.2) |

2.4 (0.9) |

6.6 (2.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 17.5 | 15.6 | 14.7 | 12.0 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 13.6 | 15.3 | 16.9 | 18.6 | 183.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.0 | 80.0 | 74.1 | 68.5 | 71.2 | 72.5 | 71.9 | 74.3 | 78.6 | 83.3 | 85.7 | 85.7 | 77.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 57.4 | 80.4 | 132.9 | 177.5 | 201.6 | 208.3 | 205.6 | 197.4 | 158.6 | 103.1 | 59.3 | 49.1 | 1,631.2 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst / SKlima.de[8] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]

Chronology

[edit]In 1989, Bonn celebrated its 2,000th anniversary. The city was commemorating the construction of the first fortified Roman camp on the Rhine in 12 BCE, after the Roman governor Agrippa had already settled the Ubii there in 38 BCE. However, people had lived in the area of today’s city much earlier. Evidence of this includes the 14,000-year-old double burial at Oberkassel as well as a trench and wooden palisades found on the Venusberg, dating back to around 4080 BCE.

In the years before the birth of Christ, Roman presence in Bonna was modest, but this changed after the Roman defeat in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE. In the following decades, a legion was stationed there, which built the Legionary Fortress Bonn in the northern part of present-day Bonn. Around the camp, and to the south along what is now Adenauerallee, traders and craftsmen settled in a vicus.

With the end of the Roman Empire, Bonn declined during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. During the Viking raids in the Rhineland, Bonn was burned twice in 882, and in 883, the recently rebuilt town was again attacked, burned, and looted by the Normans.

In the Frankish Empire, and finally in the 9th and 10th centuries, a religious center developed around the Bonn Minster (the Villa Basilika), and a market settlement emerged in the area of today’s market square. The year 1243 is considered the year in which Bonn was granted full city rights.[9]

The outcome of the Battle of Worringen in 1288 was of great importance for the further development of the city. The Cologne prince-electors made Bonn—along with Brühl and Poppelsdorf—one of their residences, and eventually their residence city. The magnificent palaces built by the prince-electors in the 17th and 18th centuries gave the city its baroque splendor.

This era ended with the occupation by French troops on October 8, 1794. This was followed by nearly two decades of occupation by the troops of Napoleon. Taxes in the form of food, clothing, and accommodations, as well as the loss of the electoral state administration, led to poverty among the population and a decline in the number of inhabitants by around 20%.[10] The French introduced a civil code (Code civil) and a municipal constitution in Bonn. Even under French occupation, medium and large industrial companies, particularly in the textile sector, were established in Bonn. The French also pursued a thorough secularization: properties of the ecclesiastical electorate, especially the electoral buildings, were taken into state ownership.[10] The areas on the right bank of the Rhine that are now part of Bonn (Vilich) came into the possession of the Prince of Nassau-Usingen; Oberkassel belonged to the Duchy of Berg, a French satellite state. By the Treaty of Lunéville of February 9, 1801, the Rhine near Bonn was designated as the French eastern border. Bonn became the seat of a sub-prefecture in the newly formed Rhin-et-Moselle.

After the defeats of the French army in the Russian campaign of 1812 and the Battle of Leipzig, the French evacuated Bonn in January 1814.

Following the decisions of the Congress of Vienna, Bonn became part of Prussia in 1815. In the following decades, the city was shaped by the newly founded University of Bonn, established by the Prussian government on October 18, 1818. The founder and namesake was King Frederick William III of Prussia. A university had existed in Bonn at the end of the 18th century but was closed during the French occupation in 1794. The Prussian foundation was not a continuation of that earlier institution, but part of a program that also included the University of Berlin and the University of Breslau. The term Rheinische in the name of the Bonn university was meant to mark it as a "sister" institution to the Berlin and Breslau universities. Over the next 100 years, Bonn became the preferred place of study for the Hohenzollern princes. It was nicknamed the "Princes' University," as both the then-Prussian Crown Prince Frederick William, his son Wilhelm, and Wilhelm's four sons studied there.[11] Other sons of noble families also favored studying at this university in the 19th century. Before the founding of the Bonn university, Cologne had been its main rival. The "enlightened tradition" of Bonn, compared to the "holy Cologne," likely made it more suitable for a confessionally neutral university. Practical reasons also favored Bonn: the old electoral palace and the Poppelsdorf Palace were already available as suitable buildings.

From 1815 onward, professors, students, civil servants, and officers arrived in Bonn, including many Protestants from the Prussian provinces, which was unusual for the predominantly Catholic Rhineland. Prussia also made Bonn a garrison town. As a result, Bonn became popular as a retirement location for military officers. Tourism also grew after German unification in 1871, fueled by the Romanticism on the Rhine of the time.

After the First World War, the city was initially occupied by Canadian, then British, and finally (until 1926) by French troops.

More than 1,000 Bonn residents, mostly of Jewish descent, were murdered during the Nazi era (Holocaust). About 8,000 people were forced to leave their hometown, were arrested, or imprisoned in concentration camps. When American troops entered Bonn on March 9, 1945, ending World War II for the city, 30% of the buildings were destroyed. Of these, 70% were slightly to severely damaged, and 30% were completely destroyed residential buildings. More than 4,000 Bonn residents had died in bombings. On May 28, 1945, Bonn became part of the British occupation zone.

After the Second World War, the city experienced rapid reconstruction and expansion, especially after the decision to make Bonn the provisional capital of the new Federal Republic of Germany instead of Frankfurt am Main on November 29, 1949[12] (see Capital of Germany#The capital debate). As a result of the law implementing the Bundestag resolution of June 20, 1991, to complete German unification (Berlin/Bonn Act)—which involved the relocation of the parliament, parts of the government, many diplomatic missions, lobbyists, and the privatization of the German Federal Post Office—the city underwent another transformation around the turn of the millennium. The remaining ministries, newly established federal agencies, headquarters of major German companies, international organizations, and institutions of science and research administration are now the drivers of this structural change, which has so far been considered successful and continues to this day.[13]

On October 30, 2014, under the patronage and active participation of Chancellor Angela Merkel, the Unity Tree Monument for German Unity was planted.[14][15][16]

Municipal Mergers The city of Bonn was enlarged several times through municipal mergers. Around 1900, Bonn grew significantly. As a result, on June 1, 1904, the towns of Poppelsdorf, Endenich, Kessenich, and Dottendorf—which had already merged physically with Bonn—were incorporated.

Through the law on the municipal reorganization of the Bonn area ("Bonn Act") of August 1, 1969, the city’s population roughly doubled, and the Sieg District was merged with the Bonn District to form the Rhein-Sieg District. The formerly independent cities of Bad Godesberg and Beuel and the municipality of Duisdorf became independent boroughs of Bonn.

The borough of Beuel, on the right bank of the Rhine, was also assigned the villages of Holzlar, Hoholz, and the Oberkassel administrative area, which had previously belonged to the Sieg District. Bonn itself was expanded with the villages of Ippendorf, Röttgen, Ückesdorf, Lessenich/Meßdorf, and Buschdorf from the former Bonn District, while Lengsdorf and Duisdorf, along with some new housing developments, formed the borough of Hardtberg.[17]

The city of Bad Godesberg had already incorporated several villages earlier. As early as 1899, Plittersdorf and Rüngsdorf had joined Godesberg, and in 1904, Friesdorf was added, effectively merging Bad Godesberg with Bonn. In 1915, Bad Godesberg expanded southwest out of the valley, leading to the incorporation of Muffendorf. On July 1, 1935, Lannesdorf and Mehlem became districts of Bad Godesberg.

Politics and government

[edit]

Mayor

[edit]

The current mayor of Bonn is Katja Dörner of Alliance 90/The Greens since 2020. She defeated incumbent mayor Ashok-Alexander Sridharan in the most recent mayoral election, which was held on 13 September 2020, with a runoff held on 27 September. The results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Ashok-Alexander Sridharan | Christian Democratic Union | 48,454 | 34.5 | 52,762 | 43.7 | |

| Katja Dörner | Alliance 90/The Greens | 38,793 | 27.6 | 67,880 | 56.3 | |

| Lissi von Bülow | Social Democratic Party | 28,389 | 20.2 | |||

| Christoph Artur Manka | Citizens' League Bonn | 8,694 | 6.2 | |||

| Michael Faber | The Left | 7,032 | 5.0 | |||

| Werner Hümmrich | Free Democratic Party | 4,853 | 3.5 | |||

| Frank Rudolf Christian Findeiß | Die PARTEI | 2,873 | 2.0 | |||

| Kaisa Ilunga | Alliance for Innovation and Justice | 1,507 | 1.1 | |||

| Valid votes | 140,595 | 99.1 | 120,642 | 99.5 | ||

| Invalid votes | 1,219 | 0.9 | 627 | 0.5 | ||

| Total | 141,814 | 100.0 | 121,269 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 249,091 | 56.9 | 249,098 | 48.7 | ||

| Source: State Returning Officer | ||||||

City council

[edit]

The Bonn city council governs the city alongside the mayor. It used to be based in the Rococo-style Altes Rathaus (old city hall), built in 1737, located adjacent to Bonn's central market square. However, due to the enlargement of Bonn in 1969 through the incorporation of Beuel and Bad Godesberg, it moved into the larger Stadthaus facilities further north. This was necessary for the city council to accommodate an increased number of representatives. The mayor of Bonn still sits in the Altes Rathaus, which is also used for representative and official purposes.

The most recent city council election was held on 13 September 2020, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 39,311 | 27.9 | 19 | |||

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 36,315 | 25.7 | 17 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 21,956 | 15.6 | 11 | |||

| Citizens' League Bonn (BBB) | 9,948 | 7.1 | 5 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 8,745 | 6.2 | 4 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 7,268 | 5.2 | 3 | |||

| Volt Germany (Volt) | 7,148 | 5.1 | New | 3 | New | |

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 4,569 | 3.2 | 2 | |||

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | 3,095 | 2.2 | New | 1 | New | |

| Alliance for Innovation and Justice (BIG) | 1,775 | 1.3 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Pirate Party Germany (Piraten) | 869 | 0.6 | 0 | |||

| Independents | 101 | 0.1 | – | 0 | – | |

| Valid votes | 141,100 | 99.3 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 1,052 | 0.7 | ||||

| Total | 142,152 | 100.0 | 66 | |||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 249,091 | 57.1 | ||||

| Source: State Returning Officer | ||||||

State government

[edit]Four delegates represent the Federal city of Bonn in the Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia. The last election took place in May 2022. The current delegates are Guido Déus (CDU), Christos Katzidis (CDU), Joachim Stamp (FDP), Tim Achtermeyer (Greens) and Dr. Julia Höller (Greens)

Federal government

[edit]Bonn's constituency is called Bundeswahlkreis Bonn (096). In the German federal election 2017, Ulrich Kelber (SPD) was elected a member of German Federal parliament, the Bundestag by direct mandate. It is his fifth term. Katja Dörner representing Bündnis 90/Die Grünen and Alexander Graf Lambsdorff for FDP were elected as well. Kelber resigned in 2019 because he was appointed Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information. As Dörner was elected Lord Mayor of Bonn in September 2020, she resigned as a member of parliament after her entry into office.

Culture

[edit]Beethoven's birthplace is located in Bonngasse near the market place. Next to the market place is the Old City Hall, built in 1737 in Rococo style, under the rule of Clemens August of Bavaria. It is used for receptions of guests of the city, and as an office for the mayor. Nearby is the Kurfürstliches Schloss, built as a residence for the prince-elector and now the main building of the University of Bonn.

The Poppelsdorfer Allee is an avenue flanked by chestnut trees which had the first horsecar of the city. It connects the Kurfürstliches Schloss with the Poppelsdorfer Schloss, a palace that was built as a resort for the prince-electors in the first half of the 18th century, and whose grounds are now a botanical garden (the Botanischer Garten Bonn). This axis is interrupted by a railway line and Bonn Hauptbahnhof, a building erected in 1883/84.

The Beethoven Monument stands on the Münsterplatz, which is flanked by the Bonn Minster, one of Germany's oldest churches.

The three highest structures in the city are the WDR radio mast in Bonn-Venusberg (180 m or 590 ft), the headquarters of the Deutsche Post called Post Tower (162.5 m or 533 ft) and the former building for the German members of parliament Langer Eugen (114.7 m or 376 ft) now the location of the UN Campus.

Churches

[edit]- Bonn Minster[18]

- Doppelkirche Schwarzrheindorf built in 1151

- Old Cemetery Bonn (Alter Friedhof), one of the best known cemeteries in Germany

- Kreuzbergkirche, built in 1627 with Johann Balthasar Neumann's Heilige Stiege, it is a stairway for Christian pilgrims

- St. Remigius, where Beethoven was baptized

Castles and residences

[edit]- Godesburg fortress ruins[19]

- The Röttgen suburb was once home to Schloss Herzogsfreude, now lost, but once a hunting lodge of elector Clemens August.

Modern buildings

[edit]

- Beethovenhalle

- Bundesviertel (federal quarter) with many government structures including

- Post Tower, the tallest building in the state North Rhine-Westphalia, housing the headquarters of Deutsche Post/DHL

- Maritim Bonn, five-star hotel and convention centre

- Schürmann-Bau, headquarters of Deutsche Welle

- Langer Eugen, since 2006 the centre of the United Nations Campus, formerly housing the offices of the members of the German parliament

- Deutsche Telekom headquarters

- Telekom Deutschland headquarters

- Kameha Grand, five-star hotel

Museums

[edit]

Just as Bonn's other four major museums, the Haus der Geschichte or Museum of the History of the Federal Republic of Germany, is located on the so-called Museumsmeile ("Museum Mile"). The Haus der Geschichte is one of the foremost German museums of contemporary German history, with branches in Berlin and Leipzig. In its permanent exhibition, the Haus der Geschichte presents German history from 1945 until the present, also shedding light on Bonn's own role as former capital of West Germany. Numerous temporary exhibitions emphasize different features, such as Nazism or important personalities in German history.[20]

The Kunstmuseum Bonn or Bonn Museum of Modern Art is an art museum founded in 1947. The Kunstmuseum exhibits both temporary exhibitions and its permanent collection. The latter is focused on Rhenish Expressionism and post-war German art.[21] German artists on display include Georg Baselitz, Joseph Beuys, Hanne Darboven, Anselm Kiefer, Blinky Palermo and Wolf Vostell. The museum owns one of the largest collections of artwork by Expressionist painter August Macke. His work is also on display in the August-Macke-Haus, located in Macke's former home where he lived from 1911 to 1914.

The Bundeskunsthalle (full name: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland or Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany), focuses on the crossroads of culture, arts, and science. To date, it attracted more than 17 million visitors.[22] One of its main objectives is to show the cultural heritage outside of Germany or Europe.[23] Next to its changing exhibitions, the Bundeskunsthalle regularly hosts concerts, discussion panels, congresses, and lectures.

The Museum Koenig is Bonn's natural history museum. Affiliated with the University of Bonn, it is also a zoological research institution housing the Leibniz-Institut für Biodiversität der Tiere. Politically interesting, it is on the premises of the Museum Koenig where the Parlamentarischer Rat first met.[24]

The Deutsches Museum Bonn, affiliated with one of the world's foremost science museums, the Deutsches Museum in Munich, is an interactive science museum focusing on post-war German scientists, engineers, and inventions.[25]

Other museums include the Beethoven House, birthplace of Ludwig van Beethoven,[26] the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn (Rhinish Regional Museum Bonn), the Bonn Women's Museum, the Rheinisches Malermuseum and the Arithmeum.

Nature

[edit]

There are several parks, leisure and protected areas in and around Bonn. The Rheinaue is Bonn's most important leisure park, with its role being comparable to what Central Park is for New York City. It lies on the banks of the Rhine and is the city's biggest park intra muros. The Rhine promenade and the Alter Zoll (Old Toll Station) are in direct neighbourhood of the city centre and are popular amongst both residents and visitors. The Arboretum Park Härle is an arboretum with specimens dating to back to 1870. The Botanischer Garten (Botanical Garden) is affiliated with the university. The natural reserve of Kottenforst is a large area of protected woods on the hills west of the city centre. It is about 40 square kilometres (15 square miles) in area and part of the Rhineland Nature Park (1,045 km2 or 403 sq mi).

In the very south of the city, on the border with Wachtberg and Rhineland-Palatinate, there is an extinct volcano, the Rodderberg, featuring a popular area for hikes. Also south of the city, there is the Siebengebirge which is part of the lower half of the Middle Rhine region. The nearby upper half of the Middle Rhine from Bingen to Koblenz is a UNESCO World Heritage Site with more than 40 castles and fortresses from the Middle Ages and important German vineyards.

Transportation

[edit]Air traffic

[edit]

Named after Konrad Adenauer, the first post-war Chancellor of West Germany, Cologne Bonn Airport is situated 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) north-east from the city centre of Bonn. With around 10.3 million passengers passing through it in 2015, it is the seventh-largest passenger airport in Germany and the third-largest in terms of cargo operations. By traffic units, which combines cargo and passengers, the airport is in fifth position in Germany.[27] As of March 2015, Cologne Bonn Airport had services to 115 passenger destinations in 35 countries.[28] The airport is one of Germany's few 24-hour airports, and is a hub for Eurowings and cargo operators FedEx Express and UPS Airlines.

The federal motorway (Autobahn) A59 connects the airport with the city. Long distance and regional trains to and from the airport stop at Cologne/Bonn Airport station. Another major airport within a one-hour drive by car is Düsseldorf International Airport.

Rail and bus system

[edit]

Bonn's central railway station, Bonn Hauptbahnhof is the city's main public transportation hub. It lies just outside the old town and near the central university buildings. It is served by regional (S-Bahn and Regionalbahn) and long-distance (IC and ICE) trains. Daily, more than 67,000 people travel via Bonn Hauptbahnhof. In late 2016, around 80 long distance and more than 165 regional trains departed to or from Bonn every day.[29][30][31] Another long-distance station, (Siegburg/Bonn), is located in the nearby town of Siegburg and serves as Bonn's station on the high-speed rail line between Cologne and Frankfurt, offering faster connections to Southern Germany. It can be reached by Stadtbahn line 66 (approx. 25 minutes from central Bonn).

Bonn has a Stadtbahn light rail and a tram system. The Bonn Stadtbahn has 4 regular lines that connect the main north–south axis (centre to Bad Godesberg) and quarters east of the Rhine (Beuel and Oberkassel), as well as many nearby towns like Brühl, Wesseling, Sankt Augustin, Siegburg, Königswinter, and Bad Honnef. All lines serve the Central Station and two lines continue to Cologne, where they connect to the Cologne Stadtbahn. The Bonn tram system consists of two lines that connect closer quarters in the south, north and east of Bonn to the Central Station. While the Stadtbahn mostly has its own right-of-way, the tram often operates on general road lanes. A few sections of track are used by both systems. These urban rail lines are supplemented by a bus system of roughly 30 regular lines, especially since some parts of the city like Hardtberg and most of Bad Godesberg completely lack a Stadtbahn/Tram connection. Several lines offer night services, especially during the weekends. Bonn is part of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Sieg (Rhine-Sieg Transport Association) which is the public transport association covering the area of the Cologne/Bonn Region.

Road network

[edit]

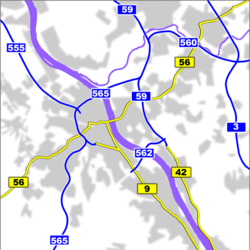

Four Autobahns run through or are adjacent to Bonn: the A59 (right bank of the Rhine, connecting Bonn with Düsseldorf and Duisburg), the A555 (left bank of the Rhine, connecting Bonn with Cologne), the A562 (connecting the right with the left bank of the Rhine south of Bonn), and the A565 (connecting the A59 and the A555 with the A61 to the southwest). Three Bundesstraßen, which have a general 100 kilometres per hour (62 miles per hour) speed limit in contrast to the Autobahn, connect Bonn to its immediate surroundings (Bundesstraßen B9, B42 and B56).

With Bonn being divided into two parts by the Rhine, three bridges are crucial for inner-city road traffic: the Konrad-Adenauer-Brücke (A562) in the South, the Friedrich-Ebert-Brücke (A565) in the North, and the Kennedybrücke (B56) in the centre. In addition, regular ferries operate between Bonn-Mehlem and Königswinter, Bonn-Bad Godesberg and Königswinter-Niederdollendorf, and Bonn-Graurheindorf and Niederkassel-Mondorf.

Port

[edit]Located in the northern sub-district of Graurheindorf, the inland harbour of Bonn is used for container traffic as well as oversea transport. The annual turnover amounts to around 500,000 t (490,000 long tons; 550,000 short tons). Regular passenger transport occurs to Cologne and Düsseldorf.

Economy

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2017) |

The head offices of Deutsche Telekom, its subsidiary Telekom Deutschland,[32] Deutsche Post, German Academic Exchange Service, and SolarWorld are in Bonn.

The third largest employer in the city of Bonn is the University of Bonn (including the university clinics)[33] and Stadtwerke Bonn also follows as a major employer.[34]

On the other hand, there are several traditional, nationally known private companies in Bonn such as luxury food producers Verpoorten and Kessko, the Klais organ manufacture and the Bonn flag factory.

The largest confectionery manufacturer in Europe, Haribo, has its founding headquarters (founded in 1920) and a production site in Bonn. Since April 2018, the head office of the company is located in the Rhineland-Palatinate municipality of Grafschaft.[35]

Other companies of supraregional importance are Weck Glaswerke (production site), Fairtrade, Eaton Industries (formerly Klöckner & Moeller), IVG Immobilien, Kautex Textron, SolarWorld, Vapiano and the SER Group.[36]

Education

[edit]

The Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms Universität Bonn (University of Bonn) is one of the largest universities in Germany. It is also the location of the German research institute Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) offices and of the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst – DAAD).

Private schools

[edit]- Aloisiuskolleg, a Jesuit private school in Bad Godesberg with boarding facilities

- Amos-Comenius-Gymnasium, a Protestant private school in Bad Godesberg

- Bonn International School (BIS), a private English-speaking school set in the former American Compound in the Rheinaue, which offers places from kindergarten to 12th grade. It follows the curriculum of the International Baccalaureate.

- Libysch Schule, private Arabic high school

- Independent Bonn International School, (IBIS) private primary school (serving from kindergarten, reception, and years 1 to 6)

- École de Gaulle - Adenauer, private French-speaking school serving grades pre-school ("maternelle") to grade 4 (CM1)

- Kardinal-Frings-Gymnasium (KFG), private catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne in Beuel

- Liebfrauenschule (LFS), private catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne

- Sankt-Adelheid-Gymnasium, private catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne in Beuel

- Clara-Fey-Gymnasium, private Catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne in Bad Godesberg

- Ernst-Kalkuhl-Gymnasium, private boarding and day school in Oberkassel

- Otto-Kühne-Schule ("PÄDA"), private day school in Bad Godesberg

- Collegium Josephinum Bonn ("CoJoBo"), private catholic day school

- Akademie für Internationale Bildung, private higher educational facility offering programs for international students

- Former schools

- King Fahd Academy, private Islamic school in Bad Godesberg

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1620 | 4,500 | — |

| 1720 | 6,535 | +45.2% |

| 1732 | 8,015 | +22.6% |

| 1760 | 13,500 | +68.4% |

| 1784 | 12,644 | −6.3% |

| 1798 | 8,837 | −30.1% |

| 1808 | 8,219 | −7.0% |

| 1817 | 10,970 | +33.5% |

| 1849 | 17,688 | +61.2% |

| 1871 | 26,030 | +47.2% |

| 1890 | 39,805 | +52.9% |

| 1910 | 87,978 | +121.0% |

| 1919 | 91,410 | +3.9% |

| 1925 | 90,249 | −1.3% |

| 1933 | 98,659 | +9.3% |

| 1939 | 100,788 | +2.2% |

| 1950 | 115,394 | +14.5% |

| 1961 | 143,850 | +24.7% |

| 1966 | 136,252 | −5.3% |

| 1970 | 275,722 | +102.4% |

| 1980 | 288,148 | +4.5% |

| 1990 | 292,234 | +1.4% |

| 2001 | 306,016 | +4.7% |

| 2011 | 305,765 | −0.1% |

| 2022 | 321,544 | +5.2% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. source:[citation needed][37] | ||

As of 2011[update], Bonn had a population of 327,913. About 70% of the population was entirely of German origin, while about 100,000 people, equating to roughly 30%, were at least partly of non-German origin. The city is one of the fastest-growing municipalities in Germany and the 18th most populous city in the country. Bonn's population is predicted to surpass the populations of Wuppertal and Bochum before the year 2030.[38]

The following list shows the largest groups of origin of minorities with "migration background" in Bonn as of 31 December 2021[update].[39]

| Rank | Migration background | Population (31 December 2022) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9,428 | |

| 2 | 8,254 | |

| 3 | 6,879 | |

| 4 | 5,921 | |

| 5 | 3,976 | |

| 6 | 3,933 | |

| 7 | 3,341 | |

| 8 | 3,282 | |

| 9 | 2,744 | |

| 10 | 2,429 | |

| 11 | 2,216 | |

| 12 | 2,198 | |

| 13 | 2,043 | |

| 14 | 1,918 | |

| 15 | 1,823 | |

| 16 | 1,781 | |

| 17 | 1,764 | |

| 18 | 1,736 | |

| 19 | 1,657 | |

| 20 | 1,635 | |

| 21 | 1,579 | |

| 22 | 1,343 | |

| 23 | 1,260 | |

| 24 | 1,220 |

Sports

[edit]Bonn is home of the Telekom Baskets Bonn, the only basketball club in Germany that owns its arena, the Telekom Dome.[40]

The city also has a semi-professional football team Bonner SC which was formed in 1965 through the merger of Bonner FV and Tura Bonn.

The Bonn Gamecocks American football team play at the 12,000-capacity Stadion Pennenfeld.

The successful German Baseball team Bonn Capitals are also found in the city of Bonn.

The headquarters of the International Paralympic Committee has been located in Bonn since 1999.

International relations

[edit]Since 1983, the City of Bonn has established friendship relations with the City of Tel Aviv, Israel, and since 1988 Bonn, in former times the residence of the Princes Electors of Cologne, and Potsdam, Germany, the formerly most important residential city of the Prussian rulers, have established a city-to-city partnership.

Central Bonn is surrounded by a number of traditional towns and villages which were independent up to several decades ago. As many of those communities had already established their own contacts and partnerships before the regional and local reorganisation in 1969, the Federal City of Bonn now has a dense network of city district partnerships with European partner towns.

The city district of Bonn is a partner of the English university city of Oxford, England, UK (since 1947), of Budafok, District XXII of Budapest, Hungary (since 1991) and of Opole, Poland (officially since 1997; contacts were established 1954).

The district of Bad Godesberg has established partnerships with Saint-Cloud in France, Frascati in Italy, Windsor and Maidenhead in England, UK and Kortrijk in Belgium; a friendship agreement has been signed with the town of Yalova, Turkey.

The district of Beuel on the right bank of the Rhine and the city district of Hardtberg foster partnerships with towns in France: Mirecourt and Villemomble.

Moreover, the city of Bonn has developed a concept of international co-operation and maintains sustainability oriented project partnerships in addition to traditional city twinning, among others with Minsk in Belarus, Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia, Bukhara in Uzbekistan, Chengdu in China and La Paz in Bolivia.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] Bukhara, Uzbekistan (1999)

Bukhara, Uzbekistan (1999) Cape Coast, Ghana (2012)

Cape Coast, Ghana (2012) Chengdu, China (2009)

Chengdu, China (2009) Kherson, Ukraine (2023)

Kherson, Ukraine (2023) Minsk, Belarus (1993)

Minsk, Belarus (1993) La Paz, Bolivia (1996)

La Paz, Bolivia (1996) Potsdam, Germany (1988)

Potsdam, Germany (1988) Tel Aviv, Israel (1983)

Tel Aviv, Israel (1983) Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (1993)

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (1993)

Bonn city district is twinned with:[43]

Oxford, United Kingdom (1947)

Oxford, United Kingdom (1947) Budafok-Tétény (Budapest), Hungary (1991)

Budafok-Tétény (Budapest), Hungary (1991)

For twin towns of other city districts, see Bad Godesberg, Beuel and Hardtberg.

Notable people

[edit]Pre–20th century

[edit]

- Johann Peter Salomon (1745–1815), musician

- Franz Anton Ries (1755–1846), violinist and violin teacher

- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), composer

- Salomon Oppenheim, Jr. (1772–1828), banker

- Peter Joseph Lenné (1789–1866), gardener and landscape architect

- Friedrich von Gerolt (1797–1879), diplomat

- Karl Joseph Simrock (1802–1876), writer and specialist in German

- Wilhelm Neuland (1806–1889), composer and conductor

- Johanna Kinkel (1810–1858), composer and writer

- Moses Hess (1812–1875), philosopher and writer

- Johann Gottfried Kinkel (1815–1882), theologian, writer, and politician

- Alexander Kaufmann (1817–1893), author and archivist

- Leopold Kaufmann (1821–1898), mayor

- Julius von Haast (1822–1887), New Zealand explorer and professor of geology

- Dietrich Brandis (1824–1907), botanist

- Balduin Möllhausen (1825–1905), traveler and writer

- Maurus Wolter (1825–1890), Benedictine, founder and first abbot of the Abbey of Beuron and Beuronese Congregation

- August Reifferscheid (1835–1887), philologist

- Antonius Maria Bodewig (1839–1915), Jesuit missionary and founder

- Nathan Zuntz (1847–1920), physician

- Alexander Koenig (1858–1940), zoologist, founder of Museum Koenig in Bonn

- Alfred Philippson (1864–1953), geographer

- Johanna Elberskirchen (1864–1943), writer and activist

- Max Alsberg (1877–1933), lawyer

- Kurt Wolff (1887–1963), publisher

- Hans Riegel Sr. (1893–1945), entrepreneur, founder of Haribo

- Eduard Krebsbach (1894–1947), SS doctor in Nazi Mauthausen concentration camp, executed for war crimes

- Paul Kemp (1896–1953), actor

1900–1949

[edit]

- Hermann Josef Abs (1901–1994), board member of the Deutsche Bank

- Paul Ludwig Landsberg (1901–1944), in Sachsenhausen concentration camp, philosopher

- Heinrich Lützeler (1902–1988), philosopher, art historian, and literary scholar

- Frederick Stephani (1903–1962), film director and screenwriter

- Helmut Horten (1909–1987), entrepreneur

- Theodor Schieffer (1910–1992), historian and medievalist

- Irene Sänger-Bredt (1911–1983), mathematician and physicist

- E. F. Schumacher (1911–1977), economist

- Karl-Theodor Molinari (1915–1993), General and founding chairman of the German Armed Forces Association

- Karlrobert Kreiten (1916–1943), pianist

- Hans Walter Zech-Nenntwich (born 1916), Second Polish Republic, SS Cavalry member and war criminal

- Walther Killy (1917–1985), German literary scholar, Der Killy

- Hannjo Hasse (1921–1983), actor

- Walter Gotell (1924–1997), actor

- J. Heinrich Matthaei (1929–2025), biochemist

- Walter Eschweiler (born 1935), football referee

- Alexandra Cordes (1935–1986), writer

- Joachim Bißmeier (born 1936), actor

- Roswitha Esser (born 1941), canoeist, gold medal winner at the Olympic Games in 1964 and 1968, Sportswoman of the Year 1964

- Heide Simonis (1943–2023), author and politician (SPD), Prime Minister of Schleswig-Holstein (1993–2005)

- Paul Alger (1943–2025), football player

- Johannes Mötsch (born 1949), archivist and historian

- Klaus Ludwig (born 1949), race car driver

1950–1999

[edit]- Günter Ollenschläger (born 1951), medical and science journalist

- Hans "Hannes" Bongartz (born 1951), football player and coach

- Ivo Ringe (born 1951), German artist, Concrete Art Painter

- Christa Goetsch (born 1952), politician (Alliance '90 / The Greens)

- Michael Meert (born 1953), film author and director

- Thomas de Maizière (born 1954), politician (CDU), former Minister of Defense and of the Interior

- Gerd Faltings (born 1954), mathematician, Fields Medal winner

- Olaf Manthey (born 1955), former touring car racing driver

- Michael Kühnen (1955–1991), Neo-Nazi

- Roger Willemsen (1955–2016), publicist, author, essayist, and presenter

- Norman Rentrop (born 1957), publisher, author, and investor

- Markus Maria Profitlich (born 1960), comedian and actor

- Guido Westerwelle (1961–2016), politician (FDP), Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor of Germany from 2009 to 2011

- Mathias Dopfner (born 1963), chief executive officer of Axel Springer AG

- Nikolaus Blome (born 1963), journalist

- Maxim Kontsevich (born 1964), mathematician, Fields Medal winner

- Johannes B. Kerner (born 1964), TV presenter, Abitur at the Aloisiuskolleg, and studied in Bonn

- Anthony Baffoe (born 1965), football player, sports presenter, and actor

- Sonja Zietlow (born 1968), TV presenter

- Burkhard Garweg (born 1968), member of the Red Army Faction

- Sabriye Tenberken (born 1970), Tibetologist, founder of Braille Without Borders

- Thorsten Libotte (born 1972), writer

- Tamara Gräfin von Nayhauß (born 1972), television presenter

- Silke Bodenbender (born 1974), actress

- Juli Zeh (born 1974), writer

- Oliver Mintzlaff (born 1975), track and field athlete and sports manager, CEO of RB Leipzig

- Markus Dieckmann (born 1976), beach volleyball player

- Bernadette Heerwagen (born 1977), actress

- Melanie Amann (born 1978), journalist

- Bushido (born 1978), musician and rapper

- Sonja Fuss (born 1978), football player

- DJ Manian (born 1978), DJ of Cascada and owner of Zooland Records

- Andreas Tölzer (born 1980), judoka

- Jens Hartwig (born 1980), actor

- Natalie Horler (born 1981), front woman of the Dance Project Cascada

- Marcel Ndjeng (born 1982), football player

- Marc Zwiebler (born 1984), badminton player

- Benjamin Barg (born 1984), football player

- Alexandros Margaritis (born 1984), race car driver

- Ken Miyao (born 1986), pop singer

- Felix Reda (born 1986), politician

- Peter Scholze (born 1987), mathematician, Fields Medal winner

- Célia Šašić (born 1988), football player

- Luke Mockridge (born 1989), comedian and author

- Pius Heinz (born 1989), poker player, 2011 WSOP Main Event champion

- Jonas Wohlfarth-Bottermann (born 1990), basketball player

- Levina (born 1991), singer

- Bienvenue Basala-Mazana (born 1992), football player

- Kim Petras (born 1992), pop singer and songwriter

- Annika Beck (born 1994), tennis player

- James Hyndman (born 1962), stage actor

- Konstanze Klosterhalfen (born 1997), track and field athlete

21st century

[edit]- [[Alvar Goetze]] (born 2000), actor

- Anny Ogrezeanu (born 2001), singer and The Voice of Germany winner 2022

Note

[edit]- ^ The data from 1933 to 1999 comes from the Bonn-Friesdorf weather station, and the data from 2000 to date comes from the Bonn-Roleber weather station.

References

[edit]- ^ "Alle politisch selbständigen Gemeinden mit ausgewählten Merkmalen am 31.12.2023" (in German). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. 28 October 2024. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ Anthony James Nicholls (1997). The Bonn Republic: West German Democracy, 1945–1990. Longman. ISBN 9780582492318 – via Google Books.

- ^ tagesschau.de. "Bonn-Berlin-Gesetz: Dieselbe Prozedur wie jedes Jahr". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ Bundestag, Deutscher. "Deutscher Bundestag: Berlin-Debatte / Antrag Vollendung der Einheit Deutschlands, Drucksache 12/815". webarchiv.bundestag.de (in German). Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Amt, Auswärtiges. "Übersicht: Die Vereinten Nationen (VN) in Deutschland". Auswärtiges Amt (in German). Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "UNBonn.org". 2 December 2024. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "Wohnberechtigte Bevölkerung in der Stadt Bonn am 31.12.2014". Bonn.de (in German). Stadt Bonn. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Monatsauswertung". sklima.de (in German). SKlima. Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Heinrich Gottfried Philipp Gengler: Regesten und Urkunden zur Verfassungs- und Rechtsgeschichte der deutschen Städte im Mittelalter. Erlangen 1863, p. 250 ([1], p. 250, at Google Books).

- ^ a b Schloßmacher, Norbert (1989). Bonner Geschichte in Bildern. Cologne: Wienand. ISBN 3-87909-200-1.

- ^ Schloßmacher, Norbert (1989). Bonner Geschichte in Bildern. Stadtgeschichte in Bildern. Vol. 1. Cologne: Wienand. p. 114. ISBN 3-87909-200-1.

- ^ "NRW 2000 - Epoche NRW: Einleitung-Bonn wird Bundeshauptstad". Archived from the original on 22 May 2013.

- ^ Klaus R. Kunzmann (2004). "Und der Sieger heißt (noch) … Bonn!". DISP 156. pp. 88 ff. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Bonner Generalanzeiger: “Merkel plants ‘Unity Tree’ in Bonn”

- ^ bonnaparte.de: Merkel pflanzt Einheitsbaum in Bonn at the Wayback Machine (archived 2014-11-28)

- ^ Christian Erhardt-Maciejewski: Unity Monument: Three Trees for Unity in: KOMMUNAL, November 4, 2014; accessed November 22, 2023.

- ^ Martin Bünermann (1970). Die Gemeinden des ersten Neugliederungsprogramms in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Cologne: Deutscher Gemeindeverlag. p. 82.

- ^ "Das Bonner Münster @ Kirche in der City". Bonner-muenster.de. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Bonn Region – Sightseeing – Fortresses and castles – Godesburg mit Michaelskapelle (Fortress Godesburg with St. Michael Chapel)". 25 May 2005. Archived from the original on 25 May 2005. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ "Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Home". Hdg.de. 13 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Kunstmuseum Bonn – Overview". Kunstmuseum.bonn.de. n.d. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "MUSEUMSMEILE BONN". museumsmeilebonn.de (in German). Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ "Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany – Bonn – English Version". Kah-bonn.de. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Museum Koenig". wegderdemokratie.de. Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "MUSEUMSMEILE BONN". museumsmeilebonn.de (in German). Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ Fraunhofer-Institut für Medienkommunikation IMK (26 March 2002). "Beethoven digitally". Beethoven-haus-bonn.de. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "ADV Monthly Traffic Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Sommerflugplan 2015: Sieben neue Ziele ab Flughafen Köln/Bonn". airliners.de. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Sanierung geht in die heiße Phase". General-Anzeiger. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016.

- ^ Bettina Köhl (12 May 2017). "Der Hauptbahnhof Bonn wird saniert" [Bonn Central Station is being renovated]. General-Anzeiger (in German). Archived from the original on 1 December 2020.

- ^ "Schöne Aussichten im Hauptbahnhof Bonn". Deutsche Bahn. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016.

- ^ "Deutsche Telekom facts and figures". Telekom Deutschland. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ^ "Presentation of the University of Bonn". Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ More jobs in the region: Largest companies in terms of employees in 2012 in the IHK district of Bonn / Rhein-Sieg. Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Communication from the IHK Bonn (as of June 2012[update])

- ^ "Haribo is leaving Kessenich – almost". General-Anzeiger. 15 May 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ SER Locations, archived from the original on 8 June 2019, retrieved 2 July 2021

- ^ "Germany: States and Major Cities". Archived from the original on 1 September 2024. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "IHK Bonn/Rhein-Sieg: Bonn wächst weiter". 29 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ "Eckzahlen der aktuellen Bevölkerungsstatistik (Stichtag 31.12.2021)" (PDF). www2.bonn.de. Statistikstelle der Bundesstadt Bonn. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "Telekom Baskets Bonn – Telekom Dome – Übersicht" Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Telekom-Baskets-Bonn.de. Retrieved 8 March 2014. (in German)

- ^ "Partners across the world". bonn.de. Bonn. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "City twinnings". bonn.de. Bonn. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Städtepartnerschaften Bonn". bonn.de (in German). Bonn. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]External links

[edit]- Official website (in English) (archived)

- Tourist information

- "The Museum Mile" (archived)

- Germany's Museum of Art in Bonn

Geography

Topography and Location

Bonn is situated in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia in western Germany, approximately 24 kilometers south-southeast of Cologne, within the southern extent of the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region. The city lies along the Rhine River, which forms its western boundary and flows northward through the area, with the urban core primarily on the river's left (eastern) bank and extensions to the right bank via bridges and the Beuel district. Its central geographic coordinates are 50°44′N 7°06′E.[7][8] The municipal area spans 141.1 square kilometers, encompassing both riverine lowlands and adjacent uplands.[2][9] The topography of Bonn is dominated by the Rhine Valley's floodplain and alluvial terraces, providing relatively flat terrain near the river at elevations around 50-60 meters above sea level. Eastward from the Rhine, the landscape rises gradually across low hills and plateaus, transitioning into the Bergisches Land region with undulating elevations up to several hundred meters. The average elevation across the city is approximately 116 meters.[10][11] To the south, Bonn adjoins the Siebengebirge, a range of low volcanic mountains with peaks reaching 460 meters, influencing local microclimates and offering scenic elevations that contrast with the valley floor.[12][13] This varied terrain, ranging from Rhine-adjacent lowlands under 100 meters to peripheral heights exceeding 200 meters, supports a mix of urban development, agriculture, and forested areas, with forests covering about 39.8% of the city.[2] The Rhine's meandering course and historical terrace formations have shaped settlement patterns, concentrating denser infrastructure in the lower, flatter zones while higher grounds host residential and green spaces.[10]

Administrative Divisions

Bonn is divided into four city districts (Stadtbezirke): Bonn, Bad Godesberg, Beuel, and Hardtberg. This structure resulted from the municipal reorganization effective January 1, 1969, which merged the former city of Bonn with the surrounding Bad Godesberg, Beuel, and several parishes in the Hardtberg area to form a unitary independent city (kreisfreie Stadt).[14] Each district operates with semi-autonomous administration, including a district council (Bezirksvertretung) of 19 elected members serving five-year terms, a district mayor (Bezirksbürgermeister) selected by the council from its members, and dedicated administrative offices handling local matters such as urban planning, culture, and social services under the oversight of the city council.[15] The districts encompass a total of 56 localities (Ortsteile), which serve as the smallest administrative and statistical units for reporting demographics, infrastructure, and services. Population distribution as of December 31, 2022, reflects the central district's dominance, housing nearly half the city's residents:| District | Population | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Bonn | 156,991 | 46.4% |

| Bad Godesberg | 77,393 | 22.9% |

| Beuel | 68,642 | 20.3% |

| Hardtberg | 35,370 | 10.4% |

Climate and Environmental Conditions

Bonn experiences a temperate oceanic climate classified as Cfb under the Köppen system, characterized by mild summers, cool winters, and relatively even precipitation throughout the year.[19] Average annual temperatures range from about 2.8°C in January to 19°C in July, with yearly means around 10°C; extremes have reached 40.9°C in summer and -23°C in winter, though such outliers are rare.[20] Precipitation totals approximately 750 mm annually, distributed fairly evenly but with slightly higher amounts in summer due to convective showers, contributing to lush vegetation and minimal seasonal aridity.[19] The Rhine River's proximity moderates temperatures, buffering against extremes and fostering a humid environment that supports extensive deciduous forests and urban green spaces, including the 1,400-hectare Kottenforst and numerous parks like the Rheinwiesen.[20] Air quality remains generally good, with low particulate matter levels compared to industrial urban centers, aided by prevailing westerly winds dispersing pollutants; however, occasional inversions in winter can trap emissions from traffic and heating.[21] Bonn's residents rate local green spaces highly, with 67% deeming them good or very good in surveys, enhancing biodiversity and urban cooling amid rising heat stress from climate change.[21] Flooding poses a key environmental risk, exacerbated by the Rhine's dynamics and intensified precipitation events; notable floods in 1993, 2018, and especially 2021 caused significant inundation, with water levels exceeding 8 meters in Bonn, prompting investments in retention basins, dikes, and nature-based solutions like restored wetlands to build resilience.[22] [23] These measures aim to reduce flood risks by at least 15% by 2040 relative to 2020 baselines through combined structural and ecological strategies, reflecting broader regional efforts against climate-driven hydrological shifts.[24]History

Roman and Medieval Foundations

Bonn originated as the Roman military fortress Castra Bonnensia, established around 11 BC on the west bank of the Rhine as a strategic outpost during the Roman campaigns in Germania.[25] The site, initially a camp, expanded into a stone-built legionary base housing approximately 7,000 soldiers, primarily from Legio I Germanica after its reconstruction following the Batavian Revolt of 69–70 AD.[25] [26] Romans constructed the first known bridge across the Rhine at this location, facilitating military logistics and trade along the frontier.[25] Accompanying the fortress was a civilian vicus settlement, supported by archaeological evidence of workshops, housing, and infrastructure that persisted beyond the military presence.[26] The fortress withstood Frankish attacks in 275 and 355 AD but saw its garrison withdraw around 400 AD amid the Empire's decline, leaving behind a depopulated but enduring settlement.[26] Incorporated into the Frankish kingdom during the 5th century, the site retained its Roman name as castrum Bonna in early medieval records, evolving into a fortified civilian center under Merovingian and Carolingian rule.[27] This continuity is evidenced by 6th-century Frankish artifacts and the reuse of Roman structures in local building.[28] Medieval development accelerated in the 11th century with the founding of Bonn Minster (Bonner Münster), a Romanesque basilica constructed between 1040 and around 1250 on the site of earlier Christian structures, possibly overlying Roman-era graves including those attributed to martyred legionaries Saints Cassius and Florentius from circa 300 AD.[29] The minster served as the church for a collegiate foundation dedicated to these saints, marking Bonn's emergence as an ecclesiastical center under the influence of the Archbishopric of Cologne.[29] By the 12th–13th centuries, the settlement grew around Münsterplatz, incorporating a medieval town layout with markets and defenses, while the archbishops began establishing a palace, laying groundwork for Bonn's role in regional governance.[30]Early Modern Period to Napoleonic Era

Following conflicts with the independent city of Cologne, the Archbishop-Electors shifted their primary residence to Bonn in the late 16th century, formally establishing it as the capital of the Electorate of Cologne in 1597.[31] This move solidified Bonn's role as the administrative and cultural center for the ecclesiastical principality within the Holy Roman Empire, where the electors wielded both spiritual and temporal authority.[32] The Wittelsbach dynasty dominated the electorate from 1583 to 1761, fostering a courtly environment that attracted artists, musicians, and administrators, though the territory remained predominantly agrarian with limited industrial development. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Bonn experienced Baroque-era embellishments under successive electors. Philipp Wilhelm von der Pfalz (1615–1695) initiated expansions of the Electoral Palace (Kurkölnisches Schloss), transforming it into a fortified residence.[33] Clemens August of Bavaria, ruling from 1723 to 1761, oversaw the most extensive building campaigns, including the completion of Poppelsdorf Palace (1740–1746) as a summer retreat connected by the Poppelsdorf Allee, and commissions for churches like the Kreuzbergkirche (1746 onward).[34] These projects, often involving architects like Balthasar Neumann, enhanced Bonn's architectural profile but strained finances amid the electorate's reliance on ecclesiastical revenues and tolls.[35] The later 18th century brought Enlightenment influences under Maximilian Friedrich (1761–1784), who laid the foundation for the University of Bonn in 1777 to promote scholarship and counter secular trends.[36] His successor, Maximilian Franz (1784–1794), the brother of Emperor Joseph II, pursued reforms such as administrative centralization and cultural patronage, including support for the young Ludwig van Beethoven's education. However, the French Revolutionary Wars abruptly terminated the electorate; troops occupied Bonn without resistance in October 1794.[37] Under French control from 1794 to 1814, Bonn was integrated into the left bank of the Rhine territories annexed by the Republic in 1797 and formalized by the 1801 Treaty of Lunéville.[38] It became part of the Roer department in 1801, subject to Napoleonic administration, which imposed secularization of church lands—dissolving monasteries and confiscating properties—metrication, and the Civil Code, disrupting the old feudal and ecclesiastical order while introducing conscription and heavy taxation that burdened the population.[39] The occupation ended with Allied advances in January 1814, paving the way for Prussian incorporation at the 1815 Congress of Vienna.[40]19th Century Industrialization and Unification

In 1815, following the Congress of Vienna, Bonn was assigned to the Kingdom of Prussia as part of the Rhine Province, marking its integration into a centralized state that prioritized administrative efficiency and economic liberalization over fragmented feudal structures.[7] This shift facilitated the abolition of internal customs barriers within Prussia and laid groundwork for broader economic cohesion, as Prussian reforms emphasized merit-based governance and infrastructure investment to counterbalance the Rhineland's Catholic and liberal-leaning populace against Berlin's Protestant conservatism.[41] The founding of the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in 1818 by King Frederick William III transformed Bonn into an academic hub, drawing scholars in fields like law, philosophy, and natural sciences, which indirectly spurred demand for precision manufacturing such as laboratory instruments.[7] While the Rhineland as a whole experienced rapid heavy industrialization driven by coal and iron resources in adjacent areas like the Ruhr, Bonn's economy emphasized lighter sectors; early textile firms established under French occupation (1794–1814) persisted modestly, but the city's terrain and riverine location favored trade, viticulture, and emerging service industries over large-scale factories.[7] Prussian policies, including the 1810–1811 Stein-Hardenberg reforms extending into the Rhine Province, promoted freedom of enterprise by dismantling guild monopolies, enabling small-scale workshops in organs, flags, and switchgear, though output remained limited compared to Prussian industrial powerhouses.[42] Infrastructure advancements accelerated connectivity: the Bonn-Cologne Railway, operational from 1844, linked the city to industrial corridors, boosting commerce in Rhine shipping and local products while integrating Bonn into Prussia's expanding rail network that supported military logistics and raw material flows.[43] Prussia's leadership in the Zollverein customs union, formalized in 1834 and encompassing the Rhine Province, reduced tariffs and standardized trade, fostering export growth in Bonn's niche goods and attracting merchants, though the city's development stayed secondary to administrative and educational roles amid regional coal-driven booms.[43] Industrial activity intensified modestly toward century's end, with commerce expanding via Rhine navigation improvements, but Bonn avoided the social upheavals of proletarianization seen in heavier industrial zones.[43] Politically, Bonn's Prussian alignment positioned it within Otto von Bismarck's unification strategy, evading direct conflict during the Danish War (1864), Austro-Prussian War (1866), and Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), as Rhine garrisons provided rear support rather than front-line engagement.[7] The North German Confederation of 1867, followed by the German Empire's proclamation on January 18, 1871, at Versailles, incorporated Bonn seamlessly into the new federal structure, with its Rhine Province status preserving local autonomy under imperial oversight.[7] This unification consolidated economic gains from prior Prussian integration, stabilizing currency and legal frameworks that favored Bonn's light industries and university-driven innovation, though the city's growth trajectory emphasized stability over explosive expansion.[44]World Wars and Interwar Period

During World War I, from 1914 to 1918, daily life in Bonn was shaped by wartime exigencies, including resource rationing, labor shortages, and the conscription of thousands of local men into the Imperial German Army, contributing to the home front's endurance amid escalating hardships.[45] In the aftermath of Germany's defeat, Bonn entered the Allied occupation of the Rhineland under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which mandated demilitarization and foreign control west of the Rhine until 1930. British forces specifically occupied the Bonn-Cologne district from late 1918, enforcing reparations compliance and restricting German military activity, though tensions eased with the 1925 Locarno Treaties leading to the British withdrawal by 1926.[46] Under the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), Bonn functioned as a modest Prussian provincial seat, its economy tied to Rhine trade and agriculture while grappling with national hyperinflation in 1923 and the Great Depression after 1929, which spurred unemployment and political polarization; the University of Bonn remained a key intellectual hub, though student groups reflected broader ideological divides.[47] The Nazi regime's consolidation of power in 1933 extended to Bonn, where the NSDAP garnered substantial local backing amid economic recovery promises, enabling Gleichschaltung (coordination) of institutions. At the University of Bonn, over 20 professors, including Jewish mathematician Otto Toeplitz, were dismissed under Aryanization policies by 1935, while Jewish students faced expulsion and the local Jewish community—numbering around 500 pre-1933—suffered escalating persecution, with deportations to camps beginning in 1941 and nearly total annihilation by 1945.[48][49] World War II brought aerial bombardment to Bonn, with RAF raids—including an early 1940 attack by 45 bombers—escalating in intensity; a major assault destroyed about 700 buildings and killed 400 civilians, igniting a firestorm in the city center, yet overall damage remained moderate compared to industrial targets like Cologne, preserving much of the historic core.[50][51] U.S. forces from the 1st Infantry Division advanced into the city on March 7, 1945, securing it with limited resistance by March 9 amid the collapse of organized Wehrmacht defenses in the Rhineland.[52]Provisional Capital of West Germany (1949–1990)

Following the division of Germany after World War II, the Parliamentary Council convened in Bonn on September 1, 1948, to draft the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, marking the city's initial role in the new state's formation.[53] The Basic Law was promulgated on May 23, 1949, and Bonn was designated the provisional seat of federal institutions, a decision advocated by incoming Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who resided nearby in Rhöndorf and preferred the city's modest scale over larger centers like Frankfurt, which was seen as too commercial and symbolically permanent.[54] This choice reflected a deliberate emphasis on temporariness, signaling hope for eventual reunification without committing to a grand capital that might entrench division, while Bonn's relative intactness from wartime bombing provided practical infrastructure.[55] The German Bundestag held its first session in Bonn on September 7, 1949, in the Bundeshaus, a former teachers' academy constructed between 1930 and 1933, which served as the parliament's primary venue alongside the Bundesrat until 1999.[53] Federal ministries, the Chancellery, and diplomatic missions were housed in repurposed buildings along the Rhine, including the former Academy of Music and nearby administrative structures, fostering a compact government quarter that expanded gradually without extensive new construction to maintain the provisional character.[56] This setup supported West Germany's integration into Western alliances, hosting key events like the 1955 NATO headquarters meetings and the 1968 signing of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, while Bonn's peripheral location—about 500 km west of the inner-German border—minimized perceived provocation toward the Soviet zone.[54] The capital status spurred administrative and economic growth, attracting over 20,000 federal civil servants and international diplomats by the 1970s, which boosted local services, housing, and infrastructure like expanded rail links but preserved Bonn's small-town atmosphere compared to potential alternatives.[57] Population increased from approximately 130,000 in 1950 to around 290,000 by 1987, driven by commuting federal employees rather than massive urbanization, contributing to steady GDP per capita gains aligned with West Germany's postwar economic miracle.[58] Critics, including some architects, later noted the era's functional but uninspiring buildings as emblematic of restrained ambition, yet this modesty aligned with Adenauer's vision of a decentralized, West-oriented republic focused on recovery over ostentation.[59] By 1990, as reunification approached, Bonn's provisional role underscored the Basic Law's enduring premise of unity, paving the way for debates on relocation.[54]Reunification, Capital Relocation, and Post-1990 Adaptation

German reunification occurred on October 3, 1990, integrating the German Democratic Republic into the Federal Republic of Germany, thereby ending Bonn's status as the provisional capital established in 1949.[60] The subsequent debate centered on whether to retain Bonn or relocate to Berlin, reflecting symbolic aspirations for national unity versus practical considerations of infrastructure and economic stability. Chancellor Helmut Kohl advocated for Berlin to symbolize the end of division, while proponents of Bonn emphasized its neutrality during the Cold War and lower costs.[61] On June 20, 1991, the Bundestag voted 337 to 320 in favor of Berlin as the seat of parliament and government, a narrow margin after 12 hours of debate.[62] The Berlin/Bonn Act, enacted in 1994, implemented this decision while designating Bonn as a "federal city" and mandating that approximately one-third of federal administrative functions remain there to cushion economic fallout, including the relocation of 20 agencies from Berlin and Frankfurt to Bonn.[63][64] This compromise preserved Bonn as headquarters for six federal ministries, such as the Ministry of Defence at the Hardthöhe, and ensured second offices for others, including the Foreign Office, sustaining around 8,500 federal jobs as of 2011.[65][66][3] The relocation unfolded gradually: the Bundestag convened in Berlin's new Reichstag building in 1999, with most ministries following by 2000, though some functions persisted in Bonn.[67] Post-relocation, Bonn adapted by leveraging retained federal presence and developing as a hub for international organizations, including UN climate bodies, alongside strengths in research, education via the University of Bonn, and service sectors.[64] This diversification mitigated potential decline, positioning Bonn as Germany's secondary political center with ongoing infrastructure investments.[3]Government and Politics

Local Administration and City Council

Bonn's local administration is led by the Oberbürgermeister, directly elected by residents for a five-year term under North Rhine-Westphalia's municipal code. The position oversees executive functions, including budget implementation and departmental coordination. Guido Déus of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) serves as the current Oberbürgermeister, elected in a run-off on September 28, 2025, with 53.99% of the vote against incumbent Katja Dörner of Alliance 90/The Greens.[68] The Rat der Stadt Bonn, or city council, functions as the legislative authority, with 66 members elected via proportional representation every five years to approve ordinances, budgets, and policies. The 2025 election on September 14 yielded the CDU as the strongest party at 31.9% of votes, followed by the Greens at 26.3% and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) at 11.8%; this distribution determines seat allocation, with the CDU and Greens together holding a potential majority.[69][70] Administrative operations are structured across departments covering public order, education, social services, and urban planning, supported by staff units for digitization and efficiency.[71] The city divides into four Stadtbezirke—Bonn, Bad Godesberg, Beuel, and Hardtberg—each with a 19-member Bezirksvertretung elected concurrently to address district-specific issues like infrastructure and community services, fostering decentralized decision-making since the 1969 municipal reform.[72][14]Role in State and Federal Governance

Bonn functions as Germany's secondary federal political center, officially designated the "Bundesstadt" (Federal City) since the partial relocation of government functions to Berlin in the 1990s. Following the 1991 parliamentary decision to move the capital while preserving Bonn's administrative role, the city retained primary headquarters for six federal ministries, including the Federal Ministry of Defence at Hardthöhe barracks and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. It also hosts around 20 federal authorities, such as the Federal Network Agency and the Federal Office for Information Security, alongside secondary seats for the Federal President, Federal Chancellor, and Bundesrat. This distributed structure, with ministries maintaining offices in both cities, has been credited by city officials with enhancing Germany's administrative resilience.[73][74][75][76][64][77] The federal presence extends to international governance, with Bonn serving as a hub for United Nations activities since 1996, hosting 27 UN institutions on a dedicated campus, including secretariats for the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification. The German federal government, via the Foreign Office, actively supports this role to strengthen Bonn's position in global multilateralism.[78][79] In North Rhine-Westphalia state governance, Bonn holds no central functions, as the state capital and primary institutions are in Düsseldorf. As a kreisfreie Stadt (independent municipality) within the Cologne administrative district (Regierungsbezirk Köln), it engages in state-level coordination on regional planning, education, and infrastructure but lacks specialized seats of state authority.[80][7]Capital Relocation Controversy and Outcomes