Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lac operon

View on WikipediaThe lactose operon (lac operon) is an operon required for the transport and metabolism of lactose in E. coli and many other enteric bacteria. Although glucose is the preferred carbon source for most enteric bacteria, the lac operon allows for the effective digestion of lactose when glucose is not available through the activity of β-galactosidase.[1] Gene regulation of the lac operon was the first genetic regulatory mechanism to be understood clearly, so it has become a foremost example of prokaryotic gene regulation. It is often discussed in introductory molecular and cellular biology classes for this reason. This lactose metabolism system was used by François Jacob and Jacques Monod to determine how a biological cell knows which enzyme to synthesize. Their work on the lac operon won them the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1965.[1]

Most bacterial cells including E. coli lack introns in their genome. They also lack a nuclear membrane. Hence the gene regulation by lac operon occurs at the transcriptional level, by controlling transcription of DNA.

Bacterial operons are polycistronic transcripts that are able to produce multiple proteins from one mRNA transcript. In this case, when lactose is required as a sugar source for the bacterium, the three genes of the lac operon can be transcribed and their subsequent proteins translated: lacZ, lacY, and lacA. The gene product of lacZ is β-galactosidase which cleaves lactose, a disaccharide, into glucose and galactose. lacY encodes β-galactoside permease, a membrane protein which becomes embedded in the Plasma membrane to enable the cellular transport of lactose into the cell. Finally, lacA encodes β-galactoside transacetylase.

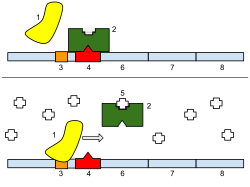

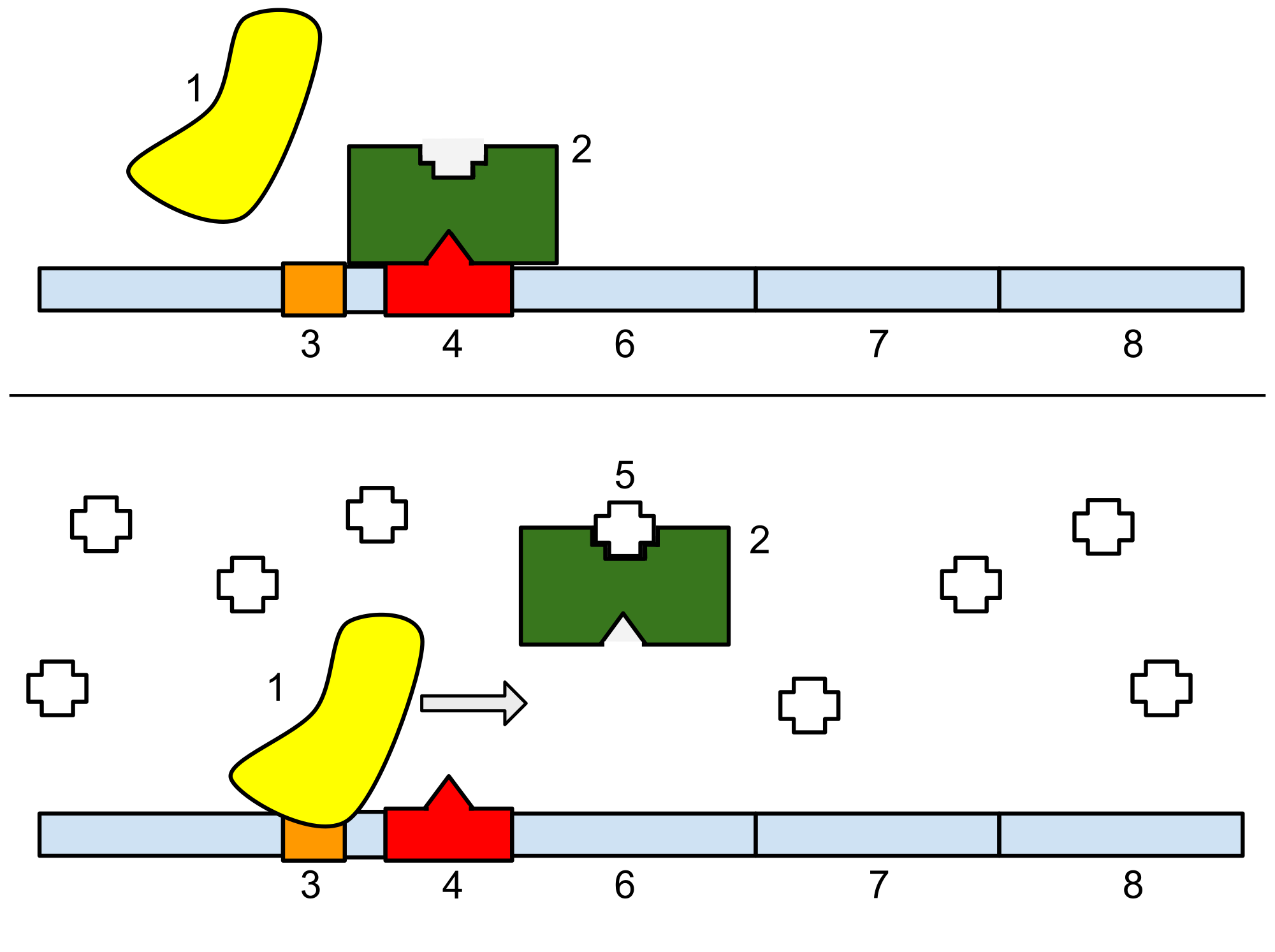

1: RNA polymerase, 2: Repressor, 3: Promoter, 4: Operator, 5: Lactose, 6: lacZ, 7: lacY, 8: lacA.

Note that the number of base pairs in diagram given above are not to scale. There are in fact over 5300 base pairs in the lac operon.[2]

It would be wasteful to produce enzymes when no lactose is available or if a preferable energy source such as glucose were available. The lac operon uses a two-part control mechanism to ensure that the cell expends energy producing the enzymes encoded by the lac operon only when necessary.[3]

In the absence of lactose, the lac repressor, encoded by lacI, halts production of the enzymes and transport proteins encoded by the lac operon.[4] It does so by blocking the DNA dependent RNA polymerase. This blocking/ halting is not perfect, and a minimal amount of gene expression does take place all the time. The repressor protein is always expressed, but the lac operon (i.e. enzymes and transport proteins) are almost completely repressed, allowing for a small level of background expression. If this weren't the case, there would be no lacY transporter protein in the cellular membrane; consequently, the lac operon would not be able to detect the presence of lactose.

When lactose is available but not glucose, then some lactose enters the cell using pre-existing transport protein encoded by lacY. This lactose then combines with the repressor and inactivates it, hence allowing the lac operon to be expressed. Then more β-galactoside permease is synthesized allowing even more lactose to enter and the enzymes encoded by lacZ and lacA can digest it.

However, in the presence of glucose, regardless of the presence of lactose, the operon will be repressed. This is because the catabolite activator protein (CAP), required for production of the enzymes, remains inactive, and EIIAGlc shuts down lactose permease to prevent transport of lactose into the cell. This dual control mechanism causes the sequential utilization of glucose and lactose in two distinct growth phases, known as diauxie.

Structure

[edit]

- The lac operon consists of 3 structural genes, and a promoter, a terminator, regulator, and an operator. The three structural genes are: lacZ, lacY, and lacA.

- lacZ encodes β-galactosidase (LacZ), an intracellular enzyme that cleaves the disaccharide lactose into glucose and galactose.

- lacY encodes β-galactoside permease (LacY), a transmembrane symporter that pumps β-galactosides including lactose into the cell using a proton gradient in the same direction. Permease increases the permeability of the cell to β-galactosides.

- lacA encodes β-galactoside transacetylase (LacA), an enzyme that transfers an acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to thiogalactoside.

Only lacZ and lacY appear to be necessary for lactose catabolic pathway.

By numbers, lacI has 1100 bps, lacZ has 3000 bps, lacY has 800 bps, lacA has 800 bps, with 3 bps corresponding to 1 amino acid.[5]

Genetic nomenclature

[edit]Three-letter abbreviations are used to describe phenotypes in bacteria including E. coli.

Examples include:

- Lac (the ability to use lactose),

- His (the ability to synthesize the amino acid histidine)

- Mot (swimming motility)

- SmR (resistance to the antibiotic streptomycin)

In the case of Lac, wild type cells are Lac+ and are able to use lactose as a carbon and energy source, while Lac− mutant derivatives cannot use lactose. The same three letters are typically used (lower-case, italicized) to label the genes involved in a particular phenotype, where each different gene is additionally distinguished by an extra letter. The lac genes encoding enzymes are lacZ, lacY, and lacA. The fourth lac gene is lacI, encoding the lactose repressor—"I" stands for inducibility.

One may distinguish between structural genes encoding enzymes, and regulatory genes encoding proteins that affect gene expression. Current usage expands the phenotypic nomenclature to apply to proteins: thus, LacZ is the protein product of the lacZ gene, β-galactosidase. Various short sequences that are not genes also affect gene expression, including the lac promoter, lac p, and the lac operator, lac o. Although it is not strictly standard usage, mutations affecting lac o are referred to as lac oc, for historical reasons.

Regulation

[edit]Specific control of the lac genes depends on the availability of the substrate lactose to the bacterium. The proteins are not produced by the bacterium when lactose is unavailable as a carbon source. The lac genes are organized into an operon; that is, they are oriented in the same direction immediately adjacent on the chromosome and are co-transcribed into a single polycistronic mRNA molecule. Transcription of all genes starts with the binding of the enzyme RNA polymerase (RNAP), a DNA-binding protein, which binds to a specific DNA binding site, the promoter, immediately upstream of the genes. Binding of RNA polymerase to the promoter is aided by the cAMP-bound catabolite activator protein (CAP, also known as the cAMP receptor protein).[6] However, the lacI gene (regulatory gene for lac operon) produces a protein that blocks RNAP from binding to the operator of the operon. This protein can only be removed when allolactose binds to it, and inactivates it. The protein that is formed by the lacI gene is known as the lac repressor. The type of regulation that the lac operon undergoes is referred to as negative inducible, meaning that the gene is turned off by the regulatory factor (lac repressor) unless some molecule (lactose) is added. Once the repressor is removed, RNAP then proceeds to transcribe all three genes (lacZYA) into mRNA. Each of the three genes on the mRNA strand has its own Shine-Dalgarno sequence, so the genes are independently translated.[7] The DNA sequence of the E. coli lac operon, the lacZYA mRNA, and the lacI genes are available from GenBank (view).

The first control mechanism is the regulatory response to lactose, which uses an intracellular regulatory protein called the lactose repressor to hinder production of β-galactosidase in the absence of lactose. The lacI gene coding for the repressor lies nearby the lac operon and is always expressed (constitutive). If lactose is missing from the growth medium, the repressor binds very tightly to a short DNA sequence just downstream of the promoter near the beginning of lacZ called the lac operator. The repressor binding to the operator interferes with binding of RNAP to the promoter, and therefore mRNA encoding LacZ and LacY is only made at very low levels. When cells are grown in the presence of lactose, however, a lactose metabolite called allolactose, made from lactose by the product of the lacZ gene, binds to the repressor, causing an allosteric shift. Thus altered, the repressor is unable to bind to the operator, allowing RNAP to transcribe the lac genes and thereby leading to higher levels of the encoded proteins.

The second control mechanism is a response to glucose, which uses the catabolite activator protein (CAP) homodimer to greatly increase production of β-galactosidase in the absence of glucose. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is a signal molecule whose prevalence is inversely proportional to that of glucose. It binds to the CAP, which in turn allows the CAP to bind to the CAP binding site (a 16 bp DNA sequence upstream of the promoter on the left in the diagram below, about 60 bp upstream of the transcription start site),[8] which assists the RNAP in binding to the DNA. In the absence of glucose, the cAMP concentration is high and binding of CAP-cAMP to the DNA significantly increases the production of β-galactosidase, enabling the cell to hydrolyse lactose and release galactose and glucose.

More recently inducer exclusion was shown to block expression of the lac operon when glucose is present. Glucose is transported into the cell by the PEP-dependent phosphotransferase system. The phosphate group of phosphoenolpyruvate is transferred via a phosphorylation cascade consisting of the general PTS (phosphotransferase system) proteins HPr and EIA and the glucose-specific PTS proteins EIIAGlc and EIIBGlc, the cytoplasmic domain of the EII glucose transporter. Transport of glucose is accompanied by its phosphorylation by EIIBGlc, draining the phosphate group from the other PTS proteins, including EIIAGlc. The unphosphorylated form of EIIAGlc binds to the lac permease and prevents it from bringing lactose into the cell. Therefore, if both glucose and lactose are present, the transport of glucose blocks the transport of the inducer of the lac operon.[9]

Repressor structure

[edit]

The lac repressor is a four-part protein, a tetramer, with identical subunits. Each subunit contains a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif capable of binding to DNA. The operator site where repressor binds is a DNA sequence with inverted repeat symmetry. The two DNA half-sites of the operator together bind to two of the subunits of the repressor. Although the other two subunits of repressor are not doing anything in this model, this property was not understood for many years.

Eventually it was discovered that two additional operators are involved in lac regulation.[10] One (O3) lies about −90 bp upstream of O1 in the end of the lacI gene, and the other (O2) is about +410 bp downstream of O1 in the early part of lacZ. These two sites were not found in the early work because they have redundant functions and individual mutations do not affect repression very much. Single mutations to either O2 or O3 have only 2 to 3-fold effects. However, their importance is demonstrated by the fact that a double mutant defective in both O2 and O3 is dramatically de-repressed (by about 70-fold).

In the current model, lac repressor is bound simultaneously to both the main operator O1 and to either O2 or O3. The intervening DNA loops out from the complex. The redundant nature of the two minor operators suggests that it is not a specific looped complex that is important. One idea is that the system works through tethering; if bound repressor releases from O1 momentarily, binding to a minor operator keeps it in the vicinity, so that it may rebind quickly. This would increase the affinity of repressor for O1.

Mechanism of induction

[edit]

The repressor is an allosteric protein, i.e. it can assume either one of two slightly different shapes, which are in equilibrium with each other. In one form the repressor will bind to the operator DNA with high specificity, and in the other form it has lost its specificity. According to the classical model of induction, binding of the inducer, either allolactose or IPTG, to the repressor affects the distribution of repressor between the two shapes. Thus, repressor with inducer bound is stabilized in the non-DNA-binding conformation. However, this simple model cannot be the whole story, because repressor is bound quite stably to DNA, yet it is released rapidly by addition of inducer. Therefore, it seems clear that an inducer can also bind to the repressor when the repressor is already bound to DNA. It is still not entirely known what the exact mechanism of binding is.[11]

Role of non-specific binding

[edit]Non-specific binding of the repressor to DNA plays a crucial role in the repression and induction of the Lac-operon. The specific binding site for the Lac-repressor protein is the operator. The non-specific interaction is mediated mainly by charge-charge interactions while binding to the operator is reinforced by hydrophobic interactions. Additionally, there is an abundance of non-specific DNA sequences to which the repressor can bind. Essentially, any sequence that is not the operator, is considered non-specific. Studies have shown, that without the presence of non-specific binding, induction (or unrepression) of the Lac-operon could not occur even with saturated levels of inducer. It had been demonstrated that, without non-specific binding, the basal level of induction is ten thousand times smaller than observed normally. This is because the non-specific DNA acts as sort of a "sink" for the repressor proteins, distracting them from the operator. The non-specific sequences decrease the amount of available repressor in the cell. This in turn reduces the amount of inducer required to unrepress the system.[12]

Lactose analogs

[edit]

A number of lactose derivatives or analogs have been described that are useful for work with the lac operon. These compounds are mainly substituted galactosides, where the glucose moiety of lactose is replaced by another chemical group.

- Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) is frequently used as an inducer of the lac operon for physiological work.[1] IPTG binds to repressor and inactivates it, but is not a substrate for β-galactosidase. One advantage of IPTG for in vivo studies is that since it cannot be metabolized by E. coli. Its concentration remains constant and the rate of expression of lac p/o-controlled genes is not a variable in the experiment. IPTG intake is dependent on the action of lactose permease in P. fluorescens, but not in E. coli.[13]

- Phenyl-β-D-galactose (phenyl-Gal) is a substrate for β-galactosidase, but does not inactivate repressor and so is not an inducer. Since wild type cells produce very little β-galactosidase, they cannot grow on phenyl-Gal as a carbon and energy source. Mutants lacking repressor are able to grow on phenyl-Gal. Thus, minimal medium containing only phenyl-Gal as a source of carbon and energy is selective for repressor mutants and operator mutants. If 108 cells of a wild type strain are plated on agar plates containing phenyl-Gal, the rare colonies which grow are mainly spontaneous mutants affecting the repressor. The relative distribution of repressor and operator mutants is affected by the target size. Since the lacI gene encoding repressor is about 50 times larger than the operator, repressor mutants predominate in the selection.

- Thiomethyl galactoside [TMG] is another lactose analog. These inhibit the lacI repressor. At low inducer concentrations, both TMG and IPTG can enter the cell through the lactose permease. However at high inducer concentrations, both analogs can enter the cell independently. TMG can reduce growth rates at high extracellular concentrations.[14]

- Other compounds serve as colorful indicators of β-galactosidase activity.

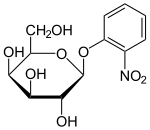

- ONPG is cleaved to produce the intensely yellow compound, orthonitrophenol and galactose, and is commonly used as a substrate for assay of β-galactosidase in vitro.[15]

- Colonies that produce β-galactosidase are turned blue by X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactoside) which is an artificial substrate for B-galactosidase whose cleavage results in galactose and 4-Cl,3-Br indigo thus producing a deep blue color.[16]

- Allolactose is an isomer of lactose and is the inducer of the lac operon. Lactose is galactose-β(1→4)-glucose, whereas allolactose is galactose-β(1→6)-glucose. Lactose is converted to allolactose by β-galactosidase in an alternative reaction to the hydrolytic one. A physiological experiment which demonstrates the role of LacZ in production of the "true" inducer in E. coli cells is the observation that a null mutant of lacZ can still produce LacY permease when grown with IPTG, a non-hydrolyzable analog of allolactose, but not when grown with lactose. The explanation is that processing of lactose to allolactose (catalyzed by β-galactosidase) is needed to produce the inducer inside the cell.

Development of the classic model

[edit]The experimental microorganism used by François Jacob and Jacques Monod was the common laboratory bacterium, E. coli, but many of the basic regulatory concepts that were discovered by Jacob and Monod are fundamental to cellular regulation in all organisms.[17] The key idea is that proteins are not synthesized when they are not needed—E. coli conserves cellular resources and energy by not making the three Lac proteins when there is no need to metabolize lactose, such as when other sugars like glucose are available. The following section discusses how E. coli controls certain genes in response to metabolic needs.

During World War II, Monod was testing the effects of combinations of sugars as nutrient sources for E. coli and B. subtilis. Monod was following up on similar studies that had been conducted by other scientists with bacteria and yeast. He found that bacteria grown with two different sugars often displayed two phases of growth. For example, if glucose and lactose were both provided, glucose was metabolized first (growth phase I, see Figure 2) and then lactose (growth phase II). Lactose was not metabolized during the first part of the diauxic growth curve because β-galactosidase was not made when both glucose and lactose were present in the medium. Monod named this phenomenon diauxie.[18]

Monod then focused his attention on the induction of β-galactosidase formation that occurred when lactose was the sole sugar in the culture medium.[19]

Classification of regulatory mutants

[edit]A conceptual breakthrough of Jacob and Monod[20] was to recognize the distinction between regulatory substances and sites where they act to change gene expression. A former soldier, Jacob used the analogy of a bomber that would release its lethal cargo upon receipt of a special radio transmission or signal. A working system requires both a ground transmitter and a receiver in the airplane. Now, suppose that the usual transmitter is broken. This system can be made to work by introduction of a second, functional transmitter. In contrast, he said, consider a bomber with a defective receiver. The behavior of this bomber cannot be changed by introduction of a second, functional aeroplane.

To analyze regulatory mutants of the lac operon, Jacob developed a system by which a second copy of the lac genes (lacI with its promoter, and lacZYA with promoter and operator) could be introduced into a single cell. A culture of such bacteria, which are diploid for the lac genes but otherwise normal, is then tested for the regulatory phenotype. In particular, it is determined whether LacZ and LacY are made even in the absence of IPTG (due to the lactose repressor produced by the mutant gene being non-functional). This experiment, in which genes or gene clusters are tested pairwise, is called a complementation test.

This test is illustrated in the figure (lacA is omitted for simplicity). First, certain haploid states are shown (i.e. the cell carries only a single copy of the lac genes). Panel (a) shows repression, (b) shows induction by IPTG, and (c) and (d) show the effect of a mutation to the lacI gene or to the operator, respectively. In panel (e) the complementation test for repressor is shown. If one copy of the lac genes carries a mutation in lacI, but the second copy is wild type for lacI, the resulting phenotype is normal—but lacZ is expressed when exposed to inducer IPTG. Mutations affecting repressor are said to be recessive to wild type (and that wild type is dominant), and this is explained by the fact that repressor is a small protein which can diffuse in the cell. The copy of the lac operon adjacent to the defective lacI gene is effectively shut off by protein produced from the second copy of lacI.

If the same experiment is carried out using an operator mutation, a different result is obtained (panel (f)). The phenotype of a cell carrying one mutant and one wild type operator site is that LacZ and LacY are produced even in the absence of the inducer IPTG; because the damaged operator site, does not permit binding of the repressor to inhibit transcription of the structural genes. The operator mutation is dominant. When the operator site where repressor must bind is damaged by mutation, the presence of a second functional site in the same cell makes no difference to expression of genes controlled by the mutant site.

A more sophisticated version of this experiment uses marked operons to distinguish between the two copies of the lac genes and show that the unregulated structural gene(s) is(are) the one(s) next to the mutant operator (panel (g). For example, suppose that one copy is marked by a mutation inactivating lacZ so that it can only produce the LacY protein, while the second copy carries a mutation affecting lacY and can only produce LacZ. In this version, only the copy of the lac operon that is adjacent to the mutant operator is expressed without IPTG. We say that the operator mutation is cis-dominant, it is dominant to wild type but affects only the copy of the operon which is immediately adjacent to it.

This explanation is misleading in an important sense, because it proceeds from a description of the experiment and then explains the results in terms of a model. But in fact, it is often true that the model comes first, and an experiment is fashioned specifically to test the model. Jacob and Monod first imagined that there must be a site in DNA with the properties of the operator, and then designed their complementation tests to show this.

The dominance of operator mutants also suggests a procedure to select them specifically. If regulatory mutants are selected from a culture of wild type using phenyl-Gal, as described above, operator mutations are rare compared to repressor mutants because the target-size is so small. But if instead we start with a strain which carries two copies of the whole lac region (that is diploid for lac), the repressor mutations (which still occur) are not recovered because complementation by the second, wild type lacI gene confers a wild type phenotype. In contrast, mutation of one copy of the operator confers a mutant phenotype because it is dominant to the second, wild type copy.

Regulation by cyclic AMP

[edit]Source:[21]

Explanation of diauxie depended on the characterization of additional mutations affecting the lac genes other than those explained by the classical model. Two other genes, cya and crp, subsequently were identified that mapped far from lac, and that, when mutated, result in a decreased level of expression in the presence of IPTG and even in strains of the bacterium lacking the repressor or operator. The discovery of cAMP in E. coli led to the demonstration that mutants defective the cya gene but not the crp gene could be restored to full activity by the addition of cAMP to the medium.

The cya gene encodes adenylate cyclase, which produces cAMP. In a cya mutant, the absence of cAMP makes the expression of the lacZYA genes more than ten times lower than normal. Addition of cAMP corrects the low Lac expression characteristic of cya mutants. The second gene, crp, encodes a protein called catabolite activator protein (CAP) or cAMP receptor protein (CRP).[22]

However the lactose metabolism enzymes are made in small quantities in the presence of both glucose and lactose (sometimes called leaky expression) due to the fact that the RNAP can still sometimes bind and initiate transcription even in the absence of CAP. Leaky expression is necessary in order to allow for metabolism of some lactose after the glucose source is expended, but before lac expression is fully activated.

In summary:

- When lactose is absent then there is very little Lac enzyme production (the operator has Lac repressor bound to it).

- When lactose is present but a preferred carbon source (like glucose) is also present then a small amount of enzyme is produced (Lac repressor is not bound to the operator).

- When glucose is absent, CAP-cAMP binds to a specific DNA site upstream of the promoter and makes a direct protein-protein interaction with RNAP that facilitates the binding of RNAP to the promoter.

The delay between growth phases reflects the time needed to produce sufficient quantities of lactose-metabolizing enzymes. First, the CAP regulatory protein has to assemble on the lac promoter, resulting in an increase in the production of lac mRNA. More available copies of the lac mRNA results in the production (see translation) of significantly more copies of LacZ (β-galactosidase, for lactose metabolism) and LacY (lactose permease to transport lactose into the cell). After a delay needed to increase the level of the lactose metabolizing enzymes, the bacteria enter into a new rapid phase of cell growth.

Two puzzles of catabolite repression relate to how cAMP levels are coupled to the presence of glucose, and secondly, why the cells should even bother. After lactose is cleaved it actually forms glucose and galactose (easily converted to glucose). In metabolic terms, lactose is just as good a carbon and energy source as glucose. The cAMP level is related not to intracellular glucose concentration but to the rate of glucose transport, which influences the activity of adenylate cyclase. (In addition, glucose transport also leads to direct inhibition of the lactose permease.) As to why E. coli works this way, one can only speculate. All enteric bacteria ferment glucose, which suggests they encounter it frequently. It is possible that a small difference in efficiency of transport or metabolism of glucose v. lactose makes it advantageous for cells to regulate the lac operon in this way.[23]

Use in molecular biology

[edit]The lac gene and its derivatives are amenable to use as a reporter gene in a number of bacterial-based selection techniques such as two hybrid analysis, in which the successful binding of a transcriptional activator to a specific promoter sequence must be determined.[16] In LB plates containing X-gal, the colour change from white colonies to a shade of blue corresponds to about 20–100 β-galactosidase units, while tetrazolium lactose and MacConkey lactose media have a range of 100–1000 units, being most sensitive in the high and low parts of this range respectively.[16] Since MacConkey lactose and tetrazolium lactose media both rely on the products of lactose breakdown, they require the presence of both lacZ and lacY genes. The many lac fusion techniques which include only the lacZ gene are thus suited to X-gal plates[16] or ONPG liquid broths.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Griffiths, Anthony J.F.; Wessler, Susan R.; Carroll, Sean B.; Doebley, John (2015). An Introduction to Genetic Analysis (11 ed.). Freeman, W.H. & Company. pp. 400–412. ISBN 9781464109485.

- ^ Sanganeria, Tanisha; Bordoni, Bruno (2024), "Genetics, Inducible Operon", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 33232031, retrieved 20 June 2024

- ^ McClean, Phillip (1997). "Prokaryotic Gene Expression". ndsu.edu. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "Prokaryotic Gene Expression". ndsu.edu. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "2.6: The lac Operon; CAP site; DNA footprinting". Biology LibreTexts. 3 January 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ Busby S., Ebright RH. (2001). "Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP)". J. Mol. Biol. 293 (2): 199–213. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3161. PMID 10550204.

- ^ Kennell, David; Riezman, Howard (July 1977). "Transcription and translation initiation frequencies of the Escherichia coli lac operon". Journal of Molecular Biology. 114 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(77)90279-0. PMID 409848.

- ^ Malan, T. Philip; Kolb, Annie; Buc, Henri; McClure, William (December 1984). "Mechanism of CRP-cAMP Activation of lac Operon Transcription Initiation Activation of the P1 Promoter". J. Mol. Biol. 180 (4): 881–909. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(84)90262-6. PMID 6098691.

- ^ Görke B, Stülke J (August 2008). "Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 6 (8): 613–24. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1932. PMID 18628769. S2CID 8782171.

- ^ Oehler, S.; Eismann, E. R.; Krämer, H.; Müller-Hill, B. (1990). "The three operators of the lac operon cooperate in repression". The EMBO Journal. 9 (4): 973–979. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08199.x. PMC 551766. PMID 2182324.

- ^ Griffiths, Anthony JF; Gelbart, William M.; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Lewontin, Richard C. (1999). "Regulation of the Lactose System". Modern Genetic Analysis. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-3118-5.

- ^ von Hippel, P.H.; Revzin, A.; Gross, C.A.; Wang, A.C. (December 1974). "Non-specific DNA binding of genome regulating proteins as a biological control mechanism: I. The lac operon: equilibrium aspects". PNAS. 71 (12): 4808–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.12.4808. PMC 433986. PMID 4612528.

- ^ Hansen LH, Knudsen S, Sørensen SJ (June 1998). "The effect of the lacY gene on the induction of IPTG inducible promoters, studied in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas fluorescens". Curr. Microbiol. 36 (6): 341–7. doi:10.1007/s002849900320. PMID 9608745. S2CID 22257399. Archived from the original on 18 October 2000.

- ^ Marbach A, Bettenbrock K (January 2012). "lac operon induction in Escherichia coli: Systematic comparison of IPTG and TMG induction and influence of the transacetylase LacA". Journal of Biotechnology. 157 (1): 82–88. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.10.009. PMID 22079752.

- ^ "ONPG (β-Galactosidase) test". September 2000. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d Joung J, Ramm E, Pabo C (2000). "A bacterial two-hybrid selection system for studying protein–DNA and protein–protein interactions". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97 (13): 7382–7. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.7382J. doi:10.1073/pnas.110149297. PMC 16554. PMID 10852947.

- ^ "Milestone 2 – A visionary pair : Nature Milestones in gene expression". www.nature.com. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Muller-Hill, Benno (1996). The lac Operon, a Short History of a Genetic Paradigm. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 7–10. ISBN 3-11-014830-7.

- ^ McKnight, Steven L. (1992). Transcriptional Regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. pp. 3–24. ISBN 0-87969-410-6.

- ^ Jacob F.; Monod J (June 1961). "Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins". J Mol Biol. 3 (3): 318–56. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(61)80072-7. PMID 13718526.

- ^ Montminy, M. (1997). "Transcriptional regulation by cyclic AMP". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 66: 807–822. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.807. ISSN 0066-4154. PMID 9242925.

- ^ Botsford, J L; Harman, J G (March 1992). "Cyclic AMP in prokaryotes". Microbiological Reviews. 56 (1): 100–122. doi:10.1128/MMBR.56.1.100-122.1992. ISSN 0146-0749. PMC 372856. PMID 1315922.

- ^ Vazquez A, Beg QK, Demenezes MA, et al. (2008). "Impact of the solvent capacity constraint on E. coli metabolism". BMC Syst Biol. 2 7. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-2-7. PMC 2270259. PMID 18215292.

- ^ "Induction of the lac operon in E. coli" (PDF). SAPS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

External links

[edit]- Lac+Operon at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- lac operon in NCBI Bookshelf [2]

- Virtual Cell Animation Collection Introducing: The Lac Operon

- The 'lac Operon: Bozeman Science

- Staining Whole Mouse Embryos for β-Galactosidase (lacZ) Activity

- Lac Operon Model Explained