Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

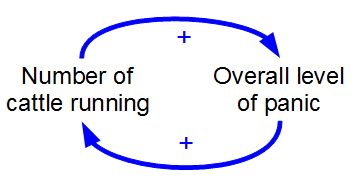

Positive feedback

View on Wikipedia

Positive feedback (exacerbating feedback, self-reinforcing feedback) is a process that occurs in a feedback loop where the outcome of a process reinforces the inciting process to build momentum. As such, these forces can exacerbate the effects of a small disturbance. That is, the effects of a perturbation on a system include an increase in the magnitude of the perturbation.[1] That is, A produces more of B which in turn produces more of A.[2] In contrast, a system in which the results of a change act to reduce or counteract it has negative feedback.[1][3] Both concepts play an important role in science and engineering, including biology, chemistry, and cybernetics.

Mathematically, positive feedback is defined as a positive loop gain around a closed loop of cause and effect.[1][3] That is, positive feedback is in phase with the input, in the sense that it adds to make the input larger.[4][5] Positive feedback tends to cause system instability. When the loop gain is positive and above 1, there will typically be exponential growth, increasing oscillations, chaotic behavior or other divergences from equilibrium.[3] System parameters will typically accelerate towards extreme values, which may damage or destroy the system, or may end with the system latched into a new stable state. Positive feedback may be controlled by signals in the system being filtered, damped, or limited, or it can be cancelled or reduced by adding negative feedback.

Positive feedback is used in digital electronics to force voltages away from intermediate voltages into '0' and '1' states. On the other hand, thermal runaway is a type of positive feedback that can destroy semiconductor junctions. Positive feedback in chemical reactions can increase the rate of reactions, and in some cases can lead to explosions. Positive feedback in mechanical design causes tipping-point, or over-centre, mechanisms to snap into position, for example in switches and locking pliers. Out of control, it can cause bridges to collapse. Positive feedback in economic systems can cause boom-then-bust cycles. A familiar example of positive feedback is the loud squealing or howling sound produced by audio feedback in public address systems: the microphone picks up sound from its own loudspeakers, amplifies it, and sends it through the speakers again.

Overview

[edit]Positive feedback enhances or amplifies an effect by it having an influence on the process which gave rise to it. For example, when part of an electronic output signal returns to the input, and is in phase with it, the system gain is increased.[6] The feedback from the outcome to the originating process can be direct, or it can be via other state variables.[3] Such systems can give rich qualitative behaviors, but whether the feedback is instantaneously positive or negative in sign has an extremely important influence on the results.[3] Positive feedback reinforces and negative feedback moderates the original process. Positive and negative in this sense refer to loop gains greater than or less than zero, and do not imply any value judgements as to the desirability of the outcomes or effects.[7] A key feature of positive feedback is thus that small disturbances get bigger. When a change occurs in a system, positive feedback causes further change, in the same direction.

Basic

[edit]

A simple feedback loop is shown in the diagram. If the loop gain AB is positive, then a condition of positive or regenerative feedback exists.

If the functions A and B are linear and AB is smaller than unity, then the overall system gain from the input to output is finite but can be very large as AB approaches unity.[8] In that case, it can be shown that the overall or loop gain from input to output is:

When AB > 1, the system is unstable, so does not have a well-defined gain; the gain may be called infinite.

Thus depending on the feedback, state changes can be convergent, or divergent. The result of positive feedback is to augment changes, so that small perturbations may result in big changes.

A system in equilibrium in which there is positive feedback to any change from its current state may be unstable, in which case the system is said to be in an unstable equilibrium. The magnitude of the forces that act to move such a system away from its equilibrium is an increasing function of the distance of the state from the equilibrium.

Positive feedback does not necessarily imply instability of an equilibrium, for example stable on and off states may exist in positive-feedback architectures.[9]

Hysteresis

[edit]

In the real world, positive feedback loops typically do not cause ever-increasing growth but are modified by limiting effects of some sort. According to Donella Meadows:

- "Positive feedback loops are sources of growth, explosion, erosion, and collapse in systems. A system with an unchecked positive loop ultimately will destroy itself. That's why there are so few of them. Usually, a negative loop will kick in sooner or later."[10]

Hysteresis, in which the starting point affects where the system ends up, can be generated by positive feedback. When the gain of the feedback loop is above 1, then the output moves away from the input: if it is above the input, then it moves towards the nearest positive limit, while if it is below the input then it moves towards the nearest negative limit.

Once it reaches the limit, it will be stable. However, if the input goes past the limit,[clarification needed] then the feedback will change sign[dubious – discuss] and the output will move in the opposite direction until it hits the opposite limit. The system therefore shows bistable behaviour.

Terminology

[edit]The terms positive and negative were first applied to feedback before World War II. The idea of positive feedback was already current in the 1920s with the introduction of the regenerative circuit.[11]

Friis & Jensen (1924) described regeneration in a set of electronic amplifiers as a case where the "feed-back" action is positive in contrast to negative feed-back action, which they mention only in passing.[12] Harold Stephen Black's classic 1934 paper first details the use of negative feedback in electronic amplifiers. According to Black:

- "Positive feed-back increases the gain of the amplifier, negative feed-back reduces it."[13]

According to Mindell (2002) confusion in the terms arose shortly after this:

- "...Friis and Jensen had made the same distinction Black used between 'positive feed-back' and 'negative feed-back', based not on the sign of the feedback itself but rather on its effect on the amplifier's gain. In contrast, Nyquist and Bode, when they built on Black's work, referred to negative feedback as that with the sign reversed. Black had trouble convincing others of the utility of his invention in part because confusion existed over basic matters of definition."[11]: 121

These confusions, along with the everyday associations of positive with good and negative with bad, have led many systems theorists to propose alternative terms. For example, Donella Meadows prefers the terms reinforcing and balancing feedbacks.[14]

Examples and applications

[edit]In electronics

[edit]

Regenerative circuits were invented and patented in 1914[15] for the amplification and reception of very weak radio signals. Carefully controlled positive feedback around a single transistor amplifier can multiply its gain by 1,000 or more.[16] Therefore, a signal can be amplified 20,000 or even 100,000 times in one stage, that would normally have a gain of only 20 to 50. The problem with regenerative amplifiers working at these very high gains is that they easily become unstable and start to oscillate. The radio operator has to be prepared to tweak the amount of feedback fairly continuously for good reception. Modern radio receivers use the superheterodyne design, with many more amplification stages, but much more stable operation and no positive feedback.

The oscillation that can break out in a regenerative radio circuit is used in electronic oscillators. By the use of tuned circuits or a piezoelectric crystal (commonly quartz), the signal that is amplified by the positive feedback remains linear and sinusoidal. There are several designs for such harmonic oscillators, including the Armstrong oscillator, Hartley oscillator, Colpitts oscillator, and the Wien bridge oscillator. They all use positive feedback to create oscillations.[17]

Many electronic circuits, especially amplifiers, incorporate negative feedback. This reduces their gain, but improves their linearity, input impedance, output impedance, and bandwidth, and stabilises all of these parameters, including the loop gain. These parameters also become less dependent on the details of the amplifying device itself, and more dependent on the feedback components, which are less likely to vary with manufacturing tolerance, age and temperature. The difference between positive and negative feedback for AC signals is one of phase: if the signal is fed back out of phase, the feedback is negative and if it is in phase the feedback is positive. One problem for amplifier designers who use negative feedback is that some of the components of the circuit will introduce phase shift in the feedback path. If there is a frequency (usually a high frequency) where the phase shift reaches 180°, then the designer must ensure that the amplifier gain at that frequency is very low (usually by low-pass filtering). If the loop gain (the product of the amplifier gain and the extent of the positive feedback) at any frequency is greater than one, then the amplifier will oscillate at that frequency (Barkhausen stability criterion). Such oscillations are sometimes called parasitic oscillations. An amplifier that is stable in one set of conditions can break into parasitic oscillation in another. This may be due to changes in temperature, supply voltage, adjustment of front-panel controls, or even the proximity of a person or other conductive item.

Amplifiers may oscillate gently in ways that are hard to detect without an oscilloscope, or the oscillations may be so extensive that only a very distorted or no required signal at all gets through, or that damage occurs. Low frequency parasitic oscillations have been called 'motorboating' due to the similarity to the sound of a low-revving exhaust note.[18]

Many common digital electronic circuits employ positive feedback. While normal simple Boolean logic gates usually rely simply on gain to push digital signal voltages away from intermediate values to the values that are meant to represent Boolean '0' and '1', but many more complex gates use feedback. When an input voltage is expected to vary in an analogue way, but sharp thresholds are required for later digital processing, the Schmitt trigger circuit uses positive feedback to ensure that if the input voltage creeps gently above the threshold, the output is forced smartly and rapidly from one logic state to the other. One of the corollaries of the Schmitt trigger's use of positive feedback is that, should the input voltage move gently down again past the same threshold, the positive feedback will hold the output in the same state with no change. This effect is called hysteresis: the input voltage has to drop past a different, lower threshold to 'un-latch' the output and reset it to its original digital value. By reducing the extent of the positive feedback, the hysteresis-width can be reduced, but it can not entirely be eradicated. The Schmitt trigger is, to some extent, a latching circuit.[19]

An electronic flip-flop, or "latch", or "bistable multivibrator", is a circuit that due to high positive feedback is not stable in a balanced or intermediate state. Such a bistable circuit is the basis of one bit of electronic memory. The flip-flop uses a pair of amplifiers, transistors, or logic gates connected to each other so that positive feedback maintains the state of the circuit in one of two unbalanced stable states after the input signal has been removed until a suitable alternative signal is applied to change the state.[20] Computer random access memory (RAM) can be made in this way, with one latching circuit for each bit of memory.[21]

Thermal runaway occurs in electronic systems because some aspect of a circuit is allowed to pass more current when it gets hotter, then the hotter it gets, the more current it passes, which heats it some more and so it passes yet more current. The effects are usually catastrophic for the device in question. If devices have to be used near to their maximum power-handling capacity, and thermal runaway is possible or likely under certain conditions, improvements can usually be achieved by careful design.[22]

Audio and video systems can demonstrate positive feedback. If a microphone picks up the amplified sound output of loudspeakers in the same circuit, then howling and screeching sounds of audio feedback (at up to the maximum power capacity of the amplifier) will be heard, as random noise is re-amplified by positive feedback and filtered by the characteristics of the audio system and the room.

Audio and live music

[edit]Audio feedback (also known as acoustic feedback, simply as feedback, or the Larsen effect) is a special kind of positive feedback which occurs when a sound loop exists between an audio input (for example, a microphone or guitar pickup) and an audio output (for example, a loudly-amplified loudspeaker). In this example, a signal received by the microphone is amplified and passed out of the loudspeaker. The sound from the loudspeaker can then be received by the microphone again, amplified further, and then passed out through the loudspeaker again. The frequency of the resulting sound is determined by resonance frequencies in the microphone, amplifier, and loudspeaker, the acoustics of the room, the directional pick-up and emission patterns of the microphone and loudspeaker, and the distance between them. For small PA systems the sound is readily recognized as a loud squeal or screech.

Feedback is almost always considered undesirable when it occurs with a singer's or public speaker's microphone at an event using a sound reinforcement system or PA system. Audio engineers use various electronic devices, such as equalizers and, since the 1990s, automatic feedback detection devices to prevent these unwanted squeals or screeching sounds, which detract from the audience's enjoyment of the event. On the other hand, since the 1960s, electric guitar players in rock music bands using loud guitar amplifiers and distortion effects have intentionally created guitar feedback to create a desirable musical effect. "I Feel Fine" by the Beatles marks one of the earliest examples of the use of feedback as a recording effect in popular music. It starts with a single, percussive feedback note produced by plucking the A string on Lennon's guitar. Artists such as the Kinks and the Who had already used feedback live, but Lennon remained proud of the fact that the Beatles were perhaps the first group to deliberately put it on vinyl. In one of his last interviews, he said, "I defy anybody to find a record—unless it's some old blues record in 1922—that uses feedback that way."[23]

The principles of audio feedback were first discovered by Danish scientist Søren Absalon Larsen. Microphones are not the only transducers subject to this effect. Phone cartridges can do the same, usually in the low-frequency range below about 100 Hz, manifesting as a low rumble. Jimi Hendrix was an innovator in the intentional use of guitar feedback in his guitar solos to create unique sound effects. He helped develop the controlled and musical use of audio feedback in electric guitar playing,[24] and later Brian May was a famous proponent of the technique.[25]

Video

[edit]Similarly, if a video camera is pointed at a monitor screen that is displaying the camera's own signal, then repeating patterns can be formed on the screen by positive feedback. This video feedback effect was used in the opening sequences to the first ten seasons of the television program Doctor Who.

Switches

[edit]In electrical switches, including bimetallic strip based thermostats, the switch usually has hysteresis in the switching action. In these cases hysteresis is mechanically achieved via positive feedback within a tipping point mechanism. The positive feedback action minimises the length of time arcing occurs for during the switching and also holds the contacts in an open or closed state.[26]

In biology

[edit]

In physiology

[edit]A number of examples of positive feedback systems may be found in physiology.

- One example is the onset of contractions in childbirth, known as the Ferguson reflex. When a contraction occurs, the hormone oxytocin causes a nerve stimulus, which stimulates the hypothalamus to produce more oxytocin, which increases uterine contractions. This results in contractions increasing in amplitude and frequency.[27]: 924–925

- Another example is the process of blood clotting. The loop is initiated when injured tissue releases signal chemicals that activate platelets in the blood. An activated platelet releases chemicals to activate more platelets, causing a rapid cascade and the formation of a blood clot.[27]: 392–394

- Lactation also involves positive feedback in that as the baby suckles on the nipple there is a nerve response into the spinal cord and up into the hypothalamus of the brain, which then stimulates the pituitary gland to produce more prolactin to produce more milk.[27]: 926

- A spike in estrogen during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle causes ovulation.[27]: 907

- The generation of nerve signals is another example, in which the membrane of a nerve fibre causes slight leakage of sodium ions through sodium channels, resulting in a change in the membrane potential, which in turn causes more opening of channels, and so on (Hodgkin cycle). So a slight initial leakage results in an explosion of sodium leakage which creates the nerve action potential.[27]: 59

- In excitation–contraction coupling of the heart, an increase in intracellular calcium ions to the cardiac myocyte is detected by ryanodine receptors in the membrane of the sarcoplasmic reticulum which transport calcium out into the cytosol in a positive feedback physiological response.

In most cases, such feedback loops culminate in counter-signals being released that suppress or break the loop. Childbirth contractions stop when the baby is out of the mother's body. Chemicals break down the blood clot. Lactation stops when the baby no longer nurses.[27]

In gene regulation

[edit]Positive feedback is a well-studied phenomenon in gene regulation, where it is most often associated with bistability. Positive feedback occurs when a gene activates itself directly or indirectly via a double negative feedback loop. Genetic engineers have constructed and tested simple positive feedback networks in bacteria to demonstrate the concept of bistability.[28] A classic example of positive feedback is the lac operon in E. coli. Positive feedback plays an integral role in cellular differentiation, development, and cancer progression, and therefore, positive feedback in gene regulation can have significant physiological consequences. Random motions in molecular dynamics coupled with positive feedback can trigger interesting effects, such as create population of phenotypically different cells from the same parent cell.[29] This happens because noise can become amplified by positive feedback. Positive feedback can also occur in other forms of cell signaling, such as enzyme kinetics or metabolic pathways.[30]

In evolutionary biology

[edit]Positive feedback loops have been used to describe aspects of the dynamics of change in biological evolution. For example, beginning at the macro level, Alfred J. Lotka (1945) argued that the evolution of the species was most essentially a matter of selection that fed back energy flows to capture more and more energy for use by living systems.[31] At the human level, Richard D. Alexander (1989) proposed that social competition between and within human groups fed back to the selection of intelligence thus constantly producing more and more refined human intelligence.[32] Crespi (2004) discussed several other examples of positive feedback loops in evolution.[33] The analogy of evolutionary arms races provides further examples of positive feedback in biological systems.[34]

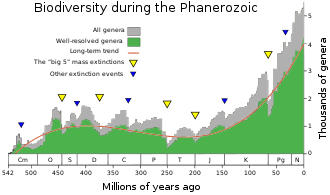

It has been shown that changes in biodiversity through the Phanerozoic correlate much better with hyperbolic model (widely used in demography and macrosociology) than with exponential and logistic models (traditionally used in population biology and extensively applied to fossil biodiversity as well). The latter models imply that changes in diversity are guided by first-order positive feedback (more ancestors, more descendants) or a negative feedback arising from resource limitation. The hyperbolic model implies a second-order positive feedback. The hyperbolic pattern of the world population growth has been demonstrated (see below) to arise from second-order positive feedback between the population size and the rate of technological growth. The hyperbolic character of biodiversity growth can be similarly accounted for by a positive feedback between the diversity and community structure complexity. It has been suggested that the similarity between the curves of biodiversity and human population probably comes from the fact that both are derived from the interference of the hyperbolic trend (produced by the positive feedback) with cyclical and stochastic dynamics.[35][36]

Immune system

[edit]A cytokine storm, or hypercytokinemia is a potentially fatal immune reaction consisting of a positive feedback loop between cytokines and immune cells, with highly elevated levels of various cytokines.[37] In normal immune function, positive feedback loops can be utilized to enhance the action of B lymphocytes. When a B cell binds its antibodies to an antigen and becomes activated, it begins releasing antibodies and secreting a complement protein called C3. Both C3 and a B cell's antibodies can bind to a pathogen, and when a B cell has its antibodies bind to a pathogen with C3, it speeds up that B cell's secretion of more antibodies and more C3, thus creating a positive feedback loop.[38]

Cell death

[edit]Apoptosis is a caspase-mediated process of cellular death, whose aim is the removal of long-lived or damaged cells. A failure of this process has been implicated in prominent conditions such as cancer or Parkinson's disease. The very core of the apoptotic process is the auto-activation of caspases, which may be modelled via a positive-feedback loop. This positive feedback exerts an auto-activation of the effector caspase by means of intermediate caspases. When isolated from the rest of apoptotic pathway, this positive feedback presents only one stable steady state, regardless of the number of intermediate activation steps of the effector caspase.[9] When this core process is complemented with inhibitors and enhancers of caspases effects, this process presents bistability, thereby modelling the alive and dying states of a cell.[39]

In psychology

[edit]Winner (1996) described gifted children as driven by positive feedback loops involving setting their own learning course, this feeding back satisfaction, thus further setting their learning goals to higher levels and so on.[40] Winner termed this positive feedback loop as a rage to master. Vandervert (2009a, 2009b) proposed that the child prodigy can be explained in terms of a positive feedback loop between the output of thinking/performing in working memory, which then is fed to the cerebellum where it is streamlined, and then fed back to working memory thus steadily increasing the quantitative and qualitative output of working memory.[41][42] Vandervert also argued that this working memory/cerebellar positive feedback loop was responsible for language evolution in working memory.

In economics

[edit]Markets with social influence

[edit]Product recommendations and information about past purchases have been shown to influence consumers' choices significantly whether it is for music, movie, book, technological, and other type of products. Social influence often induces a rich-get-richer phenomenon (Matthew effect) where popular products tend to become even more popular.[43]

Market dynamics

[edit]According to the theory of reflexivity advanced by George Soros, price changes are driven by a positive feedback process whereby investors' expectations are influenced by price movements so their behaviour acts to reinforce movement in that direction until it becomes unsustainable, whereupon the feedback drives prices in the opposite direction.[44]

In social media

[edit]Programs such as Facebook and Twitter depend on positive feedback to create interest in topics and drive the take-up of the media.[45][46] In the age of smartphones and social media, the feedback loop has created a craze for virtual validation in the form of likes, shares, and FOMO (fear of missing out).[47] This is intensified by the use of bots which are designed to respond to particular words or themes and transmit posts more widely. [48]

What is called negative feedback in social media should often be regarded as positive feedback in this context. Outrageous statements and negative comments often produce much more feedback than positive comments.

Systemic risk

[edit]Systemic risk is the risk that an amplification or leverage or positive feedback process presents to a system. This is usually unknown, and under certain conditions, this process can amplify exponentially and rapidly lead to destructive or chaotic behaviour. A Ponzi scheme is a good example of a positive-feedback system: funds from new investors are used to pay out unusually high returns, which in turn attract more new investors, causing rapid growth toward collapse. W. Brian Arthur has also studied and written on positive feedback in the economy (e.g. W. Brian Arthur, 1990).[49] Hyman Minsky proposed a theory that certain credit expansion practices could make a market economy into "a deviation amplifying system" that could suddenly collapse,[50] sometimes called a Minsky moment.

Simple systems that clearly separate the inputs from the outputs are not prone to systemic risk. This risk is more likely as the complexity of the system increases because it becomes more difficult to see or analyze all the possible combinations of variables in the system even under careful stress testing conditions. The more efficient a complex system is, the more likely it is to be prone to systemic risks because it takes only a small amount of deviation to disrupt the system. Therefore, well-designed complex systems generally have built-in features to avoid this condition, such as a small amount of friction, or resistance, or inertia, or time delay to decouple the outputs from the inputs within the system. These factors amount to an inefficiency, but they are necessary to avoid instabilities.

The 2010 Flash Crash incident was blamed on the practice of high-frequency trading (HFT),[51] although whether HFT really increases systemic risk remains controversial.[citation needed]

Human population growth

[edit]Agriculture and human population can be considered to be in a positive feedback mode,[52] which means that one drives the other with increasing intensity. It is suggested that this positive feedback system will end sometime with a catastrophe, as modern agriculture is using up all of the easily available phosphate and is resorting to highly efficient monocultures which are more susceptible to systemic risk.

Technological innovation and human population can be similarly considered, and this has been offered as an explanation for the apparent hyperbolic growth of the human population in the past, instead of a simpler exponential growth.[53] It is proposed that the growth rate is accelerating because of second-order positive feedback between population and technology.[54]: 133–160 Technological growth increases the carrying capacity of land for people, which leads to a growing population, and this in turn drives further technological growth.[54]: 146 [55]

Prejudice, social institutions and poverty

[edit]Gunnar Myrdal described a vicious circle of increasing inequalities, and poverty, which is known as circular cumulative causation.[56]

James Moody, Assistant Professor at Ohio State University, states that students who self-segregate or grow up in segregated environments have "little meaningful exposure to other races because they never form relationships with students of another race...[; as a result,...] they are viewing other racial groups at a social distance, which can bolster stereotypes," which ultimately causes a positive feedback loop in which segregated groups become more prejudiced, polarized, and segregated against each other, similar to that of political polarization.[57]

In meteorology

[edit]Drought intensifies through positive feedback. A lack of rain decreases soil moisture, which kills plants or causes them to release less water through transpiration. Both factors limit evapotranspiration, the process by which water vapour is added to the atmosphere from the surface, and add dry dust to the atmosphere, which absorbs water. Less water vapour means both low dew point temperatures and more efficient daytime heating, decreasing the chances of humidity in the atmosphere leading to cloud formation. Lastly, without clouds, there cannot be rain, and the loop is complete.[58]

In climatology

[edit]Climate forcings may push a climate system in the direction of warming or cooling,[64] for example, increased atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases cause warming at the surface. Forcings are external to the climate system and feedbacks are internal processes of the system. Some feedback mechanisms act in relative isolation to the rest of the climate system while others are tightly coupled.[65] Forcings, feedbacks and the dynamics of the climate system determine how much and how fast the climate changes. The main positive feedback in global warming is the tendency of warming to increase the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere, which in turn leads to further warming.[66] The main negative feedback comes from the Stefan–Boltzmann law, the amount of heat radiated from the Earth into space is proportional to the fourth power of the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere.

Other examples of positive feedback subsystems in climatology include:

- A warmer atmosphere melts ice, changing the albedo (surface reflectivity), which further warms the atmosphere.

- Methane hydrates can be unstable so that a warming ocean could release more methane, which is also a greenhouse gas.

- Peat, occurring naturally in peat bogs, contains carbon. When peat dries it decomposes, and may additionally burn. Peat also releases nitrous oxide.

- Global warming affects the cloud distribution. Clouds at higher altitudes enhance the greenhouse effects, while low clouds mainly reflect back sunlight, having opposite effects on temperature.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report states that "Anthropogenic warming could lead to some effects that are abrupt or irreversible, depending upon the rate and magnitude of the climate change."[67]

In sociology

[edit]A self-fulfilling prophecy is a social positive feedback loop between beliefs and behaviour: if enough people believe that something is true, their behaviour can make it true, and observations of their behaviour may in turn increase belief. A classic example is a bank run.

Another sociological example of positive feedback is the network effect. When more people are encouraged to join a network this increases the reach of the network therefore the network expands ever more quickly. A viral video is an example of the network effect in which links to a popular video are shared and redistributed, ensuring that more people see the video and then re-publish the links. This is the basis for many social phenomena, including Ponzi schemes and chain letters. In many cases, population size is the limiting factor to the feedback effect.

In political science

[edit]In politics, institutions can reinforce norms, which can subsequently be a source of positive feedback. This rationale is frequently utilized to comprehend public policy processes, which may be dissected into a sequence of events. Self-reinforcing processes are understood to be affected by positive feedback mechanisms (e.g., supportive policy constituencies).[68] Conversely, unsuccessful policy processes encounter negative feedback mechanisms (e.g., veto points with veto power).[69]

A comparative illustration of policy feedback can be observed in the economic foreign policies of Brazil and China, particularly in their execution of state capitalism tactics during the 1990s and 2000s.[70] Although both nations initially embraced similar state capitalist ideas, their paths in executing economic policies diverged over time due to distinct incentives. In China, a positive feedback mechanism reinforced previous policies, whereas in Brazil, negative feedback mechanisms compelled the country to abandon state capitalism policies and dynamics.

In chemistry

[edit]If a chemical reaction causes the release of heat, and the reaction itself happens faster at higher temperatures, then there is a high likelihood of positive feedback. If the heat produced is not removed from the reactants fast enough, thermal runaway can occur and very quickly lead to a chemical explosion.

In conservation

[edit]Many wildlife are hunted for their parts which can be quite valuable. The closer to extinction that targeted species become, the higher the price there is on their parts.[71]

See also

[edit]- Chain reaction – Self-amplifying chain of events

- Donella Meadows' twelve leverage points to intervene in a system – Systems Dynamics concept

- Hyperbolic growth – Growth function exhibiting a singularity at a finite time

- Reflexivity (social theory) – Circular relationships between cause and effect

- Stability criterion

- Strategic complements – Game theory concept

- System dynamics – Study of non-linear complex systems

- Technological singularity – Point when technology grows beyond human control

- Thermal runaway – Loss of control of an exothermal process due to temperature increases

- Negative feedback – Control concept

- Vicious/virtuous circle – Self-reinforcing sequence of events: in social and financial systems, a complex of events that reinforces itself through a feedback loop.

- Positive reinforcement: a situation in operant conditioning where a consequence increases the frequency of a behaviour.

- Praise of performance: a term often applied in the context of performance appraisal,[72] although this usage is disputed

- Self-reinforcing feedback: a term used in systems dynamics to avoid confusion with the "praise" usage

- Matthew effect – The rich get richer and the poor get poorer

- Self-fulfilling prophecy – Prediction that causes itself to become true

- Autocatalysis – Chemical reaction whose product is also its catalyst

- Meander – One of a series of curves in a channel of a matured stream

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ben Zuckerman & David Jefferson (1996). Human Population and the Environmental Crisis. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-86720-966-2. Archived from the original on 2018-01-06.

- ^ Keesing, R.M. (1981). Cultural anthropology: A contemporary perspective (2nd ed.) p.149. Sydney: Holt, Rinehard & Winston, Inc.

- ^ a b c d e

Bernard P. Zeigler; Herbert Praehofer; Tag Gon Kim Section (2000). "3.3.2 Feedback in continuous systems". Theory of Modeling and Simulation: Integrating Discrete Event and Continuous Complex Dynamic Systems. Academic Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-12-778455-7. Archived from the original on 2017-01-03.

A positive feedback loop is one with an even number of negative influences [around the loop].

- ^ S W Amos; R W Amos (2002). Newnes Dictionary of Electronics (4th ed.). Newnes. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-7506-5642-9. Archived from the original on 2017-03-29.

- ^ Rudolf F. Graf (1999). Modern Dictionary of Electronics (7th ed.). Newnes. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-7506-9866-5. Archived from the original on 2017-03-29.

- ^ "Positive feedback". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ "Feedback". Glossary. Metadesigners Network. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Electronics circuits and devices second edition. Ralph J. Smith

- ^ a b Lopez-Caamal, Fernando; Middleton, Richard H.; Huber, Heinrich (February 2014). "Equilibria and stability of a class of positive feedback loops". Journal of Mathematical Biology. 68 (3): 609–645. doi:10.1007/s00285-013-0644-z. PMID 23358701. S2CID 2954380.

- ^ Donella Meadows, Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System Archived 2013-10-08 at the Wayback Machine, 1999

- ^ a b Mindell, David A. (2002). Between Human and Machine: Feedback, Control, and Computing before Cybernetics. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6895-5. Archived from the original on 2018-01-06.

- ^ Friis, H. T.; Jensen, A. G. (April 1924), "High Frequency Amplifiers", Bell System Technical Journal, 3 (2): 181–205, doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1924.tb01354.x

- ^ Black, H. S. (January 1934), "Stabilized feed-back amplifiers", Electrical Engineering, 53: 114–120, doi:10.1109/ee.1934.6540374

- ^ Meadows, Donella H. (2009). Thinking in systems: a primer. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-600-00-1405-6.

- ^ US 1113149, Armstrong, E. H., "Wireless receiving system", published 1914-10-06

- ^ Kitchin, Charles. "A Short Wave Regenerative Receiver Project". Archived from the original on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Sinewave oscillators". EDUCYPEDIA - electronics. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Self, Douglas (2009). Audio Power Amplifier Design Handbook. Focal Press. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-0-240-52162-6. Archived from the original on 2014-01-29.

- ^ "CMOS Schmitt Trigger—A Uniquely Versatile Design Component" (PDF). Fairchild Semiconductor Application Note 140. Fairchild Semiconductors. 1975. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Strandh, Robert. "Latches and flip-flops". Laboratoire Bordelais de Recherche en Informatique. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Wayne, Storr. "Sequential Logic Basics: SR Flip-Flop". Electronics-Tutorials.ws. Archived from the original on 16 September 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Sharma, Bijay Kumar (2009). "Analog Electronics Lecture 4 Part C RC coupled Amplifier Design Procedure". Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Sheff, David (2000). All We Are Saying. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-312-25464-3.

- ^ Shadwick, Keith (2003). Jimi Hendrix, Musician. Backbeat Books. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-87930-764-6.

- ^ May, Brian. "Burns Brian May Tri-Sonic Pickups". House Music & Duck Productions. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Positive Feedback and Bistable Systems" (PDF). University of Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-13.

* Non-Hysteretic Switches, Memoryless Switches: These systems have no memory, that is, once the input signal is removed, the system returns to its original state. * Hysteretic Switches, Bistability: Bistable systems, in contrast, have memory. That is, when switched to one state or another, these systems remain in that state unless forced to change back. The light switch is a common example of a bistable system from everyday life. All bistable systems are based around some form of positive feedback loop.

- ^ a b c d e f Guyton, Arthur C. (1991) Textbook of Medical Physiology. (8th ed). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-3994-1

- ^ Hasty, J.; McMillen, D.; Collins, J. J. (2002). "Engineered gene circuits". Nature. 420 (6912): 224–230. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..224H. doi:10.1038/nature01257. PMID 12432407.

- ^ Veening, J.; Smits, W. K.; Kuipers, O. P. (2008). "Bistability, Epigenetics, and Bet-Hedging in Bacteria" (PDF). Annual Review of Microbiology. 62 (1): 193–210. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163002. hdl:11370/59bec46a-4434-4eaa-aaae-03461dd02bbb. PMID 18537474. S2CID 3747871.

- ^ Bagowski, C. P.; Ferrell, J. E. (2001). "Bistability in the JNK cascade". Current Biology. 11 (15): 1176–1182. Bibcode:2001CBio...11.1176B. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00330-X. PMID 11516948. S2CID 526628.

- ^ Lotka, A (1945). "The law of evolution as a maximal principle". Human Biology. 17: 168–194.

- ^ Alexander, R. (1989). Evolution of the human psyche. In P. Millar & C. Stringer (Eds.), The human revolution: Behavioral and biological perspectives on the origins of modern humans (pp. 455-513). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Crespi, B. J. (2004). "Vicious circles: positive feedback in major evolutionary and ecological transitions". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 19 (12): 627–633. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.10.001. PMID 16701324.

- ^ Dawkins, R. 1991. The Blind Watchmaker London: Penguin. Note: W.W. Norton also published this book, and some citations may refer to that publication. However, the text is identical, so it depends on which book is at hand

- ^ Markov, Alexander V.; Korotayev, Andrey V. (2007). "Phanerozoic marine biodiversity follows a hyperbolic trend". Palaeoworld. 16 (4): 311–318. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2007.01.002.

- ^ Markov, A.; Korotayev, A. (2008). "Hyperbolic growth of marine and continental biodiversity through the Phanerozoic and community evolution". Journal of General Biology. 69 (3): 175–194. PMID 18677962. Archived from the original on 2009-12-25.

- ^ Osterholm, Michael T. (2005-05-05). "Preparing for the Next Pandemic". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (18): 1839–1842. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.608.6200. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058068. PMID 15872196. S2CID 45893174.

- ^ Paul, William E. (September 1993). "Infectious Diseases and the Immune System". Scientific American. 269 (3): 93. Bibcode:1993SciAm.269c..90P. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0993-90. PMID 8211095.

- ^ Eissing, Thomas (2014). "Bistability analyses of a caspase activation model for receptor-induced apoptosis". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (35): 36892–36897. doi:10.1074/jbc.M404893200. PMID 15208304.

- ^ Winner, E. (1996). Gifted children: Myths and Realities. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01760-7.

- ^ Vandervert, L. (2009a). Working memory, the cognitive functions of the cerebellum and the child prodigy. In L.V. Shavinina (Ed.), International handbook on giftedness (pp. 295-316). The Netherlands: Springer Science.

- ^ Vandervert, L. (2009b). "The emergence of the child prodigy 10,000 years ago: An evolutionary and developmental explanation". Journal of Mind and Behavior. 30 (1–2): 15–32.

- ^ Altszyler, E; Berbeglia, F.; Berbeglia, G.; Van Hentenryck, P. (2017). "Transient dynamics in trial-offer markets with social influence: Trade-offs between appeal and quality". PLOS ONE. 12 (7) e0180040. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1280040A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180040. PMC 5528888. PMID 28746334.

- ^ Azzopardi, Paul V. (2010), Behavioural Technical Analysis, Harriman House Limited, p. 116, ISBN 978-0-85719-068-0, archived from the original on 2017-03-29

- ^ Burghardt, Keith; Lerman, Kristina (18 Jan 2022). Emergent Instabilities in Algorithmic Feedback Loops (Report). Cornell University. arXiv:2201.07203.

- ^ Loukides, Mike (September 24, 2019). "The biggest problem with social media has nothing to do with free speech". Gizmodo.

- ^ Benewaa, Dorcas (May 7, 2021). "Social Media And The Dopamine Feedback Loop: Here's How It Affects You". Digital Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ Reardon, Jayne (Dec 14, 2017). "Can We Avoid the Feedback Loop of Social Media?". 2Civility.

- ^ Arthur, W. Brian (1990). "Positive Feedbacks in the Economy". Scientific American. 262 (2): 80. Bibcode:1990SciAm.262b..92A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0290-92.

- ^ The Financial Instability Hypothesis Archived 2009-10-09 at the Wayback Machine by Hyman P. Minsky, Working Paper No. 74, May 1992, pp. 6–8

- ^ "Findings Regarding the Market Events of May 6, 2010" (PDF). 2010-09-30. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2017.

- ^ Brown, A. Duncan (2003), Feed or Feedback: Agriculture, Population Dynamics and the State of the Planet, Utrecht: International Books, ISBN 978-90-5727-048-2

- ^ Dolgonosov, B.M. (2010). "On the reasons of hyperbolic growth in the biological and human world systems". Ecological Modelling. 221 (13–14): 1702–1709. Bibcode:2010EcMod.221.1702D. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.03.028.

- ^ a b Korotayev A. Compact Mathematical Models of World System Development, and How they can Help us to Clarify our Understanding of Globalization Processes Archived 2018-01-06 at the Wayback Machine. Globalization as Evolutionary Process: Modeling Global Change. Edited by George Modelski, Tessaleno Devezas, and William R. Thompson. London: Routledge, 2007. P. 133-160.

- ^ Korotayev, A. V., & Malkov, A. S. A Compact Mathematical Model of the World System Economic and Demographic Growth, 1 CE–1973 CE // INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL MODELS AND METHODS IN APPLIED SCIENCES Volume 10, 2016. P. 200-209 Archived 2018-01-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Berger, Sebastian. "Circular Cumulative Causation (CCC) à la Myrdal and Kapp — Political Institutionalism for Minimizing Social Costs" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Teen Friendships More Racially Segregated at Moderately Diverse Schools: Integrated Friendships More Likely at Highly Diverse Schools | NICHD - Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development". www.nichd.nih.gov. 2002-05-28. Retrieved 2024-12-23.

- ^ S.-Y. Simon Wang; Jin-Ho Yoon; Christopher C. Funk; Robert R. Gillies, eds. (2017). Climate Extremes: Patterns and Mechanisms. Wiley. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-119-06803-7.

- ^ "The Study of Earth as an Integrated System". nasa.gov. NASA. 2016. Archived from the original on November 2, 2016.

- ^ Fig. TS.17, Technical Summary, Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), Working Group I, IPCC, 2021, p. 96. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022.

- ^ Harris, Nancy; Rose, Melissa (24 July 2025). "World's Forest Carbon Sink Shrank to its Lowest Point in at Least 2 Decades, Due to Fires and Persistent Deforestation". World Resources Institute. Chart: "Net Forest Carbon Sink (Gt CO2e/yr)"

- ^ Mulkey, Sachi Kitajima; Stevens, Harry (24 July 2025). "For 1st Time, Fires Are Biggest Threat to Forests' Climate-Fighting Superpower". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 July 2025.

- ^ a b Potapov, Peter; Tyukavina, Alexandra; Turubanova, Svetlana; Hansen, Matthew C.; et al. (21 July 2025). "Unprecedentedly high global forest disturbance due to fire in 2023 and 2024". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 122 (30) e2505418122. doi:10.1073/pnas.2505418122. PMC 12318170. PMID 40690667.

- ^ US NRC (2012), Climate Change: Evidence, Impacts, and Choices, US National Research Council (US NRC), archived from the original on 2016-05-03, p.9. Also available as PDF Archived 2013-02-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Understanding Climate Change Feedbacks, U.S. National Academy of Sciences Archived 2012-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "8.6.3.1 Water Vapour and Lapse Rate - AR4 WGI Chapter 8: Climate Models and their Evaluation". Archived from the original on 2010-04-09. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ IPCC. "Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Pg 53" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-02-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Falleti, T. G., & Mahoney, J. (2015). The comparative sequential method. In J. Mahoney & K. Thelen (Eds.), Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis (pp. 211–239). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Tsebelis, George. 2002. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Do Vale, Helder Ferreira and Costa, Lilian (2024). "State capitalism in a changing global order: Brazil and China's strategies for greater global influence". Research in Globalization, Volume 9, 100265, ISSN 2590-051X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2024.100265.

- ^ Holden, Matthew H.; McDonald-Madden, Eve (2017). "High prices for rare species can drive large populations extinct: The anthropogenic Allee effect revisited". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 429: 170–180. arXiv:1703.06736. Bibcode:2017JThBi.429..170H. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.06.019. PMID 28669883. S2CID 4877874.

- ^ Positive feedback occurs when one is told he has done something well or correctly. Tom Coens and Mary Jenkins, "Abolishing Performance Appraisals", p116.

Further reading

[edit]- Norbert Wiener (1948), Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, Paris, Hermann et Cie - MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play. MIT Press. 2004. ISBN 0-262-24045-9. Chapter 18: Games as Cybernetic Systems.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Positive feedback at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Positive feedback at Wikiquote