Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isomer

View on Wikipedia

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with an identical molecular formula – that is, the same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space.[1] Isomerism refers to the existence or possibility of isomers.

Isomers do not necessarily share similar chemical or physical properties. Two main forms of isomerism are structural (or constitutional) isomerism, in which bonds between the atoms differ; and stereoisomerism (or spatial isomerism), in which the bonds are the same but the relative positions of the atoms differ.

Isomeric relationships form a hierarchy. Two chemicals might be the same constitutional isomer, but upon deeper analysis be stereoisomers of each other. Two molecules that are the same stereoisomer as each other might be in different conformational forms or be different isotopologues. The depth of analysis depends on the field of study or the chemical and physical properties of interest.

The English word "isomer" (/ˈaɪsəmər/) is a back-formation from "isomeric",[2] which was borrowed through German isomerisch[3] from Swedish isomerisk; which in turn was coined from Greek ἰσόμερoς isómeros, with roots isos = "equal", méros = "part".[4]

Structural isomers

[edit]Structural isomers have the same number of atoms of each element (hence the same molecular formula), but the atoms are connected in distinct ways.[5]

Example: C

3H

8O

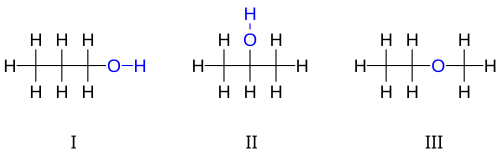

[edit]For example, there are three distinct compounds with the molecular formula :

3H

8O: I 1-propanol, II 2-propanol, III ethyl-methyl-ether.

The first two isomers shown of are propanols, that is, alcohols derived from propane. Both have a chain of three carbon atoms connected by single bonds, with the remaining carbon valences being filled by seven hydrogen atoms and by a hydroxyl group comprising the oxygen atom bound to a hydrogen atom. These two isomers differ on which carbon the hydroxyl is bound to: either to an extremity of the carbon chain propan-1-ol (1-propanol, n-propyl alcohol, n-propanol; I) or to the middle carbon propan-2-ol (2-propanol, isopropyl alcohol, isopropanol; II). These can be described by the condensed structural formulas and .

The third isomer of is the ether methoxyethane (ethyl-methyl-ether; III). Unlike the other two, it has the oxygen atom connected to two carbons, and all eight hydrogens bonded directly to carbons. It can be described by the condensed formula .

The alcohol "3-propanol" is not another isomer, since the difference between it and 1-propanol is not real; it is only the result of an arbitrary choice in the direction of numbering the carbons along the chain. For the same reason, "ethoxymethane" is the same molecule as methoxyethane, not another isomer.

1-Propanol and 2-propanol are examples of positional isomers, which differ by the position at which certain features, such as double bonds or functional groups, occur on a "parent" molecule (propane, in that case).

Example: C

3H

4

[edit]There are also three structural isomers of the hydrocarbon :

|

|

|

| I Propadiene | II Propyne | III Cyclopropene |

In two of the isomers, the three carbon atoms are connected in an open chain, but in one of them (propadiene or allene; I) the carbons are connected by two double bonds, while in the other (propyne or methylacetylene; II) they are connected by a single bond and a triple bond. In the third isomer (cyclopropene; III) the three carbons are connected into a ring by two single bonds and a double bond. In all three, the remaining valences of the carbon atoms are satisfied by the four hydrogens.

Again, note that there is only one structural isomer with a triple bond, because the other possible placement of that bond is just drawing the three carbons in a different order. For the same reason, there is only one cyclopropene, not three.

Tautomers

[edit]Tautomers are structural isomers which readily interconvert, so that two or more species co-exist in equilibrium such as

.[6]

Important examples are keto-enol tautomerism and the equilibrium between neutral and zwitterionic forms of an amino acid.

Stereoisomers

[edit]

Stereoisomers have the same atoms or isotopes connected by bonds of the same type, but differ in the relative positions of those atoms in space. Two broad types of stereoisomers exist, enantiomers and diastereomers. Enantiomers have identical physical properties but diastereomers do not.[7]

Enantiomers

[edit]Two compounds are said to be enantiomers if their molecules are mirror images of each other and cannot be made to coincide only by rotations or translations – like a left hand and a right hand. The two shapes are said to be chiral.

A classic example is bromochlorofluoromethane (). The two enantiomers can be distinguished, for example, by whether the path turns clockwise or counterclockwise as seen from the hydrogen atom. In order to change one conformation to the other, at some point those four atoms would have to lie on the same plane – which would require severely straining or breaking their bonds to the carbon atom. The corresponding energy barrier between the two conformations is so high that there is practically no conversion between them at room temperature, and they can be regarded as different configurations.

The compound chlorofluoromethane , in contrast, is not chiral; the mirror image of its molecule is also obtained by a half-turn about a suitable axis.

Another example of a chiral compound is 2,3-pentadiene , a hydrocarbon that contains two overlapping double bonds. The double bonds are such that the three middle carbons are in a straight line, while the first three and last three lie on perpendicular planes. The molecule and its mirror image are not superimposable, even though the molecule has an axis of symmetry. The two enantiomers can be distinguished, for example, by the right-hand rule. This type of isomerism is called axial isomerism.

Enantiomers behave identically in chemical reactions, except when reacting with chiral compounds or in the presence of chiral catalysts, such as most enzymes. For this latter reason, the two enantiomers of most chiral compounds usually have markedly different effects and roles in living organisms. In biochemistry and food science, the two enantiomers of a chiral molecule – such as glucose – are usually identified and treated as very different substances.

Each enantiomer of a chiral compound typically rotates the plane of polarized light that passes through it. The rotation has the same magnitude but opposite senses for the two isomers, and can be a useful way of distinguishing and measuring their concentration in a solution. For this reason, enantiomers were formerly called "optical isomers".[8][9] However, this term is ambiguous and is discouraged by the IUPAC.[10][11]

Some enantiomer pairs (such as those of trans-cyclooctene) can be interconverted by internal motions that change bond lengths and angles only slightly. Other pairs (such as CHFClBr) cannot be interconverted without breaking bonds, and therefore are different configurations.

Diastereomers

[edit]Stereoisomers that are not enantiomers are called diastereomers. Some diastereomers may contain chiral centers, and some may not.[12]

Cis-trans isomerism

[edit]A double bond between two carbon atoms forces the remaining four bonds (if they are single) to lie on the same plane, perpendicular to the plane of the bond as defined by its π orbital. If the two bonds on each carbon connect to different atoms, two distinct conformations are possible that differ from each other by a twist of 180 degrees of one of the carbons about the double bond.

The classical example is dichloroethene , specifically the structural isomer that has one chlorine bonded to each carbon. It has two conformational isomers, with the two chlorines on the same side or on opposite sides of the double bond's plane. They are traditionally called cis (from Latin meaning "on this side of") and trans ("on the other side of"), respectively, or Z and E in the IUPAC recommended nomenclature. Conversion between these two forms usually requires temporarily breaking bonds (or turning the double bond into a single bond), so the two are considered different configurations of the molecule.

More generally, cis–trans isomerism (formerly called "geometric isomerism") occurs in molecules where the relative orientation of two distinguishable functional groups is restricted by a somewhat rigid framework of other atoms.[13]

For example, in the cyclic alcohol inositol (a six-fold alcohol of cyclohexane), the six-carbon cyclic backbone largely prevents the hydroxyl and the hydrogen on each carbon from switching places. Therefore, one has different configurational isomers depending on whether each hydroxyl is on "this side" or "the other side" of the ring's mean plane. Discounting isomers that are equivalent under rotations, there are nine isomers that differ by this criterion, and behave as different stable substances (two of them being enantiomers of each other). The most common one in nature (myo-inositol) has the hydroxyls on carbons 1, 2, 3 and 5 on the same side of that plane, and can therefore be called cis-1,2,3,5-trans-4,6-cyclohexanehexol. And each of these cis-trans isomers can possibly have stable "chair" or "boat" conformations (although the barriers between these are significantly lower than those between different cis-trans isomers).

Cis and trans isomers also occur in inorganic coordination compounds, such as square planar complexes and octahedral complexes.

For more complex organic molecules, the cis and trans labels can be ambiguous. In such cases, a more precise labeling scheme is employed based on the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules.[14][12]

Isotopes and spin

[edit]Isotopomers

[edit]Different isotopes of the same element can be considered as different kinds of atoms when enumerating isomers of a molecule or ion. The replacement of one or more atoms by their isotopes can create multiple structural isomers and/or stereoisomers from a single isomer.

For example, replacing two atoms of common hydrogen () by deuterium (, or ) on an ethane molecule yields two distinct structural isomers, depending on whether the substitutions are both on the same carbon (1,1-dideuteroethane, ) or one on each carbon (1,2-dideuteroethane, ); as if the substituent was chlorine instead of deuterium. The two molecules do not interconvert easily and have different properties, such as their microwave spectrum.[15]

Another example would be substituting one atom of deuterium for one of the hydrogens in chlorofluoromethane (). While the original molecule is not chiral and has a single isomer, the substitution creates a pair of chiral enantiomers of , which could be distinguished (at least in theory) by their optical activity.[16]

When two isomers would be identical if all isotopes of each element were replaced by a single isotope, they are described as isotopomers or isotopic isomers.[17] In the above two examples if all were replaced by , the two dideuteroethanes would both become ethane and the two deuterochlorofluoromethanes would both become .

The concept of isotopomers is different from isotopologs or isotopic homologs, which differ in their isotopic composition.[17] For example, and are isotopologues and not isotopomers, and are therefore not isomers of each other.

Spin isomers

[edit]Another type of isomerism based on nuclear properties is spin isomerism, where molecules differ only in the relative spin magnetic quantum numbers ms of the constituent atomic nuclei. This phenomenon is significant for molecular hydrogen, which can be partially separated into two long-lived states described as spin isomers[18] or nuclear spin isomers:[19] parahydrogen, with the spins of the two nuclei pointing in opposite directions, and orthohydrogen, where the spins point in the same direction.

Applications

[edit]Isomers having distinct biological properties are common; for example, the placement of methyl groups. In substituted xanthines, theobromine, found in chocolate, is a vasodilator with some effects in common with caffeine; but, if one of the two methyl groups is moved to a different position on the two-ring core, the isomer is theophylline, which has a variety of effects, including bronchodilation and anti-inflammatory action. Another example of this occurs in the phenethylamine-based stimulant drugs. Phentermine is a non-chiral compound with a weaker effect than that of amphetamine. It is used as an appetite-reducing medication and has mild or no stimulant properties. However, an alternate atomic arrangement gives dextromethamphetamine, which is a stronger stimulant than amphetamine.

In medicinal chemistry and biochemistry, enantiomers are a special concern because they may possess distinct biological activity. Many preparative procedures afford a mixture of equal amounts of both enantiomeric forms. In some cases, the enantiomers are separated by chromatography using chiral stationary phases. They may also be separated through the formation of diastereomeric salts. In other cases, enantioselective synthesis have been developed.

As an inorganic example, cisplatin (see structure above) is an important drug used in cancer chemotherapy, whereas the trans isomer (transplatin) has no useful pharmacological activity.

History

[edit]Isomerism was first observed in 1827, when Friedrich Wöhler prepared silver cyanate and discovered that, although its elemental composition of was identical to silver fulminate (prepared by Justus von Liebig the previous year),[20] its properties were distinct. This finding challenged the prevailing chemical understanding of the time, which held that chemical compounds could be distinct only when their elemental compositions differ. (We now know that the bonding structures of fulminate and cyanate can be approximately described as ≡ and , respectively.)

Additional examples were found in succeeding years, such as Wöhler's 1828 discovery that urea has the same atomic composition () as the chemically distinct ammonium cyanate. (Their structures are now known to be and , respectively.) In 1830 Jöns Jacob Berzelius introduced the term isomerism to describe the phenomenon.[4][21][22][23]

In 1848, Louis Pasteur observed that tartaric acid crystals came into two kinds of shapes that were mirror images of each other. Separating the crystals by hand, he obtained two version of tartaric acid, each of which would crystallize in only one of the two shapes, and rotated the plane of polarized light to the same degree but in opposite directions.[24][25] In 1860, Pasteur explicitly hypothesized that the molecules of isomers might have the same composition but different arrangements of their atoms.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Petrucci, Ralph H.; Harwood, William S.; Herring, F. Geoffrey (2002). General chemistry: principles and modern applications (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall. p. 91]. ISBN 978-0-13-014329-7. LCCN 2001032331. OCLC 46872308.

- ^ Merriam-Webster: "isomer" Archived 21 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine online dictionary entry. Accessed on 2020-08-26

- ^ Merriam-Webster: "isomeric" Archived 26 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine online dictionary entry. Accessed on 2020-08-26

- ^ a b Jac. Berzelius (1830): "Om sammansättningen af vinsyra och drufsyra (John's säure aus den Voghesen), om blyoxidens atomvigt, samt allmänna anmärkningar om sådana kroppar som hafva lika sammansättning, men skiljaktiga egenskaper" ("On the composition of tartaric acid and racemic acid (John's acid of the Vosges), on the molecular weight of lead oxide, together with general observations on those bodies that have the same composition but distinct properties"). Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps Academiens Handling (Transactions of the Royal Swedish Science Academy), volume 49, pages 49–80

- ^ Smith, Janice Gorzynski (2010). General, Organic and Biological Chemistry (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 450. ISBN 978-0-07-302657-2.

- ^ "tautomerism". IUPAC Gold Book. IUPAC. 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.T06252. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, p. 136, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ Petrucci, Harwood & Herring 2002, pp. 996–997.

- ^ Whitten K.W., Gailey K.D. and Davis R.E. "General Chemistry" (4th ed., Saunders College Publishing 1992), p. 976–7 ISBN 978-0-03-072373-5

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "optical isomers". doi:10.1351/goldbook.O04308

- ^ Ernest L. Eliel and Samuel H. Wilen (1994). Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. Wiley Interscience. p. 1203.

- ^ a b Ernest L. Eliel and Samuel H. Wilen (1994). Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. Wiley Interscience. pp. 52–53.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "geometric isomerism". doi:10.1351/goldbook.G02620

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "cis, trans". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01092

- ^ Eizi Hirota (2012): "Microwave spectroscopy of isotope-substituted non-polar molecules". Chapter 5 in Molecular Spectroscopy: Modern Research, volume 3. 466 pages. ISBN 9780323149327

- ^ Cameron, Robert P.; Götte, Jörg B.; Barnett, Stephen M. (8 September 2016). "Chiral rotational spectroscopy". Physical Review A. 94 (3) 032505. arXiv:1511.04615. Bibcode:2016PhRvA..94c2505C. doi:10.1103/physreva.94.032505. ISSN 2469-9926.

- ^ a b Seeman, Jeffrey I.; Paine, III, J. B. (7 December 1992). "Letter to the Editor: 'Isotopomers, Isotopologs'". Chemical & Engineering News. 70 (2). American Chemical Society. doi:10.1021/cen-v070n049.p002.

- ^ Matthews, M.J.; Petitpas, G.; Aceves, S.M. (23 August 2011). "A study of spin isomer conversion kinetics in supercritical fluid hydrogen for cryogenic fuel storage technologies". Appl. Phys. Lett. 99 (8): 081906. Bibcode:2011ApPhL..99h1906M. doi:10.1063/1.3628453. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Chen, Judy Y.-C.; Li, Yongjun; Frunzi, Michael; Lei, Xuegong; Murata, Yasujiro; Lawler, Ronald G.; Turro, Nicholas (13 September 2013). "Nuclear spin isomers of guest molecules in H2@C60, H2O@C60 and other endofullerenes". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 371 (1998). Bibcode:2013RSPTA.37110628C. doi:10.1098/rsta.2011.0628. PMID 23918710. S2CID 20443766.

- ^ F. Kurzer (2000). "Fulminic Acid in the History of Organic Chemistry". J. Chem. Educ. 77 (7): 851–857. Bibcode:2000JChEd..77..851K. doi:10.1021/ed077p851. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ J. J. Berzelius (1831): "Über die Zusammensetzung der Weinsäure und Traubensäure (John's säure aus den Voghesen), über das Atomengewicht des Bleioxyds, nebst allgemeinen Bemerkungen über solche Körper, die gleiche Zusammensetzung, aber ungleiche Eigenschaften besitzen". Annalen der Physik und Chemie, volume 19, pages 305–335

- ^ J. J. Berzelius (1831): "Composition de l'acide tartarique et de l'acide racémique (traubensäure); poids atomique de l'oxide de plomb, et remarques générals sur les corps qui ont la même composition, et possèdent des proprietés différentes". Annales de Chimie et de Physique, volume 46, pages 113–147.

- ^ Esteban, Soledad (2008). "Liebig–Wöhler Controversy and the Concept of Isomerism". J. Chem. Educ. 85 (9): 1201. Bibcode:2008JChEd..85.1201E. doi:10.1021/ed085p1201. Archived from the original on 23 August 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ L. Pasteur (1848) "Mémoire sur la relation qui peut exister entre la forme cristalline et la composition chimique, et sur la cause de la polarisation rotatoire" (Memoir on the relationship which can exist between crystalline form and chemical composition, and on the cause of rotary polarization)," Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (Paris), vol. 26, pages 535–538.

- ^ L. Pasteur (1848) "Sur les relations qui peuvent exister entre la forme cristalline, la composition chimique et le sens de la polarisation rotatoire" ("On the relations that can exist between crystalline form, chemical composition, and the sense of rotary polarization"), Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 3rd series, volume 24, issue 6, pages 442–459.

- ^ Pullman (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought, p. 230

External links

[edit]Isomer

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In chemistry, an isomer is defined as one of several molecular entities that possess the same molecular formula but differ in their connectivity or spatial arrangement of atoms.[1] This results in distinct physical and chemical properties despite the identical atomic composition. Isomers arise primarily from variations in the bonding patterns (connectivity) between atoms or from different three-dimensional configurations, which can significantly influence reactivity, stability, and biological activity.[5] A fundamental prerequisite for understanding isomers is the concept of a molecular formula, which specifies the exact number and types of atoms in a molecule, such as C₄H₁₀ for the butane isomers.[5] These differences in atomic arrangement lead to compounds that, while sharing the same formula, exhibit unique behaviors under the same conditions. It is important to distinguish isomers from related concepts like isotopes and allotropes. Isotopes refer to variants of the same chemical element that have identical atomic numbers but different mass numbers due to varying numbers of neutrons in the nucleus, resulting in the same chemical formula but altered nuclear properties.[6] In contrast, allotropes are different structural forms of the same element, such as diamond and graphite for carbon, where the atomic connectivity varies but the elemental composition remains uniform.[7] Isomers, therefore, apply to compounds rather than elements or atomic nuclei. Isomers are broadly classified into constitutional isomers, which differ in atomic connectivity, and stereoisomers, which share connectivity but vary in spatial orientation.[1]Classification

Isomers are broadly classified into two primary categories: constitutional isomers and stereoisomers, based on differences in atomic connectivity and spatial arrangement, respectively.[8] Constitutional isomers, also termed structural isomers, share the same molecular formula but exhibit variations in the bonding sequence or connectivity of atoms, leading to distinct molecular structures.[1] This category is hierarchically subdivided into skeletal isomers, which differ in the arrangement of the carbon skeleton or chain branching; positional isomers, which involve differences in the location of functional groups, double bonds, or substituents along the chain; and functional isomers, which possess different functional groups despite the same overall formula.[9] In contrast, stereoisomers maintain identical atomic connectivity and molecular formula but differ in the three-dimensional orientation of atoms or groups in space.[8] Stereoisomers are further classified into enantiomers and diastereomers. Enantiomers are pairs of stereoisomers that are nonsuperimposable mirror images of each other, arising from chirality centers or other asymmetric features.[8] Diastereomers encompass all other stereoisomers that are not enantiomers, including geometric isomers (such as cis-trans isomers in alkenes or rings), which result from restricted rotation around bonds.[10] This classification hinges on the prerequisite that constitutional isomers involve altered connectivity, whereas stereoisomers presuppose identical connectivity with variations solely in spatial configuration.[8] Beyond these classical molecular isomers, related variants include isotopic and nuclear forms, which extend the concept but deviate from the standard definition of identical atomic composition. Isotopomers differ in the positional arrangement of isotopic atoms while maintaining the same isotopic composition, and isotopologues vary in their overall isotopic substitution, though these are not true isomers due to mass differences affecting the molecular formula when isotopes are distinguished.[11] Nuclear isomers, conversely, represent long-lived excited states of atomic nuclei with the same proton and neutron numbers but differing energy configurations, classified into types such as spin, shape, K-, and fission isomers based on the hindrance mechanisms for decay; these are not molecular isomers but share terminological roots in nuclear physics.[12]Constitutional Isomers

Skeletal Isomers

Skeletal isomers, also known as chain isomers, are a subtype of constitutional isomers in which compounds share the same molecular formula and functional groups but differ in the arrangement or branching of their carbon skeleton.[13] This variation in carbon connectivity leads to distinct molecular shapes while preserving the overall composition. Such isomerism is prevalent among alkanes, saturated hydrocarbons with the general molecular formula , where represents the number of carbon atoms.[14] For instance, the isomers n-butane and isobutane exemplify skeletal isomerism: n-butane features a linear carbon chain (CH₃-CH₂-CH₂-CH₃), whereas isobutane has a branched structure ((CH₃)₃CH).[15] These structural differences significantly affect physical properties, such as boiling points, due to variations in molecular shape and intermolecular forces. n-Butane boils at -0.5°C, while isobutane boils at -11.7°C; the branched isobutane adopts a more compact, spherical form, reducing surface area for van der Waals interactions and thus requiring less energy to vaporize.[16]Positional and Functional Isomers

Positional isomers are constitutional isomers that share the same carbon skeleton and functional groups but differ in the position of these groups or multiple bonds along the chain.[17] For example, 1-propanol () and 2-propanol () both have the molecular formula and a hydroxyl group, but the -OH is attached to different carbon atoms, leading to variations in boiling points and reactivity.[18] Another instance involves alkenes like 1-butene () and 2-butene (), where the double bond's location shifts, affecting stability and addition reactions.[17] Functional isomers, in contrast, possess the same molecular formula but differ in the types of functional groups present, resulting in distinct chemical behaviors despite identical atomic compositions.[19] A classic pair is ethanol () and dimethyl ether (), both , where the former features an alcohol group and the latter an ether linkage; this leads to ethanol's ability to form hydrogen bonds, yielding a higher boiling point (78.4°C) compared to dimethyl ether's (-24.8°C).[20] Similarly, propanal () and propanone (), both , represent aldehyde and ketone functional groups, influencing their oxidation products—propanal oxidizes to propanoic acid, while propanone resists further oxidation under mild conditions.[21] Metamerism represents a subtype of functional isomerism, characterized by differences in the alkyl chain lengths attached to a polyvalent functional group, such as in ethers or amines, while maintaining the same overall formula.[22] For instance, diethyl ether () and methyl propyl ether (), both , exhibit this variation around the ether oxygen, resulting in subtle differences in viscosity and solubility.[22] Metamerism is particularly relevant in compounds with divalent heteroatoms, highlighting how chain distribution impacts physical properties without altering the core functional group.[23] These isomer types often display marked differences in physicochemical properties and reactivity due to their structural variations. In functional isomers like alcohols and ethers, alcohols engage in hydrogen bonding, enhancing solubility in water and elevating boiling points relative to ethers of comparable mass.[24] Reactivity diverges significantly: alcohols undergo oxidation to aldehydes, ketones, or carboxylic acids depending on the conditions, whereas ethers are largely inert to such transformations and resist nucleophilic attack under neutral conditions.[25] Positional isomers, while sharing reactivity patterns, may show nuanced differences, such as 1-propanol's primary alcohol facilitating esterification more readily than the secondary 2-propanol.[5] Overall, these distinctions underscore the importance of precise structural analysis in predicting compound behavior.Tautomers

Tautomers represent a specialized subset of constitutional isomers that interconvert rapidly through tautomerization, a process involving the relocation of a hydrogen atom (or proton) and a concomitant rearrangement of bonds, typically a double bond shifting to maintain valence. This dynamic equilibrium distinguishes tautomers from static isomers, as the structures exist in reversible balance rather than as isolated compounds. The term "tautomer" derives from Greek roots meaning "same" and "part," reflecting their identical molecular formula but differing atomic arrangements.[26] A classic example of tautomerism is keto-enol tautomerism, observed in compounds like acetone. In its keto form, acetone exists as , featuring a carbonyl group, while the enol form is , with a hydroxyl group attached to a carbon-carbon double bond. The equilibrium strongly favors the keto tautomer, with an equilibrium constant () of approximately in aqueous solution at room temperature, indicating that less than 0.001% of acetone molecules adopt the enol form under standard conditions.[27][28] The mechanism of tautomerization generally proceeds via proton transfer, often facilitated by acid or base catalysis to overcome the activation barrier in neutral conditions. In acid-catalyzed keto-enol interconversion, the carbonyl oxygen is first protonated to form a resonance-stabilized carbocation intermediate, followed by deprotonation from the alpha carbon to yield the enol; the reverse path regenerates the keto form. Base-catalyzed mechanisms involve deprotonation at the alpha carbon to generate an enolate ion, which is then protonated on the oxygen. These pathways highlight the role of labile protons in enabling the bond shifts.[28] Tautomerism significantly influences molecular reactivity, as the distinct functional groups in each form lead to varied chemical behaviors. For instance, the enol tautomer of acetone exhibits enhanced nucleophilicity at the alpha carbon due to the electron-rich vinyl alcohol structure, facilitating reactions like electrophilic additions that are less favorable for the keto form. This duality allows tautomers to participate in diverse synthetic pathways, such as aldol condensations, where the enol or enolate acts as a nucleophile.[26] In biological contexts, tautomerism plays a critical role in nucleic acids, particularly through rare tautomeric forms of DNA bases that can lead to mutagenesis. For example, the standard keto or amino forms of bases like guanine or thymine ensure faithful Watson-Crick base pairing during replication, but transient shifts to enol or imino tautomers enable mismatched pairings (e.g., guanine with thymine instead of cytosine), with rare tautomeric forms occurring at low fractions (estimated ~10^{-4} to 10^{-6}). Such events underscore tautomerism's impact on genetic fidelity and evolutionary processes.[29][30]Stereoisomers

Enantiomers

Enantiomers are one of a pair of stereoisomers that are non-superimposable mirror images of each other. They arise from molecules that exhibit chirality, where the spatial arrangement of atoms cannot be superimposed on its mirror image. Unlike constitutional isomers, enantiomers share the same molecular formula and connectivity but differ in the configuration at one or more chiral centers. Chirality in enantiomers typically requires the presence of at least one chiral center, most commonly a tetrahedral carbon atom bonded to four different substituents, resulting in a stereogenic center.[31] This asymmetry leads to the two possible configurations, often designated as (R) and (S) according to the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules. Without such a chiral element, molecules lack the handedness necessary for enantiomerism, and their mirror images are superimposable.[32] Enantiomers possess identical physical properties, such as melting points, boiling points, and solubilities, but they differ in their interaction with plane-polarized light, rotating it in opposite directions—a phenomenon known as optical activity. The specific rotation, a measure of this effect, is equal in magnitude but opposite in sign for each enantiomer. For instance, (S)-(+)-lactic acid has a specific rotation of +3.8° at 589 nm, while its enantiomer, (R)-(-)-lactic acid, has -3.8° under the same conditions.[33] This optical distinction arises because chiral molecules absorb left- and right-circularly polarized light differently. A racemic mixture, or racemate, consists of equal proportions of both enantiomers and exhibits no net optical rotation due to mutual cancellation. Such mixtures are common in synthesis without chiral control and can be resolved into pure enantiomers using techniques like chiral chromatography. Enantiomers of one compound may form diastereomeric relationships with stereoisomers of related compounds, leading to differing properties in those contexts. Fischer projections provide a conventional two-dimensional representation of enantiomers, depicting the chiral center as a cross with horizontal bonds projecting forward and vertical bonds receding. For lactic acid, the (S) enantiomer is shown with the hydroxyl group on the left in the standard orientation, contrasting with the (R) form on the right. This method facilitates visualization of the mirror-image relationship without three-dimensional models.Diastereomers

Diastereomers are defined as stereoisomers that are not mirror images of one another and thus not enantiomers.[34] They arise in molecules with two or more chiral centers, where the stereoisomers differ in configuration at one or more, but not all, of these centers.[35] This configuration difference leads to distinct spatial arrangements that result in varying physical and chemical properties, unlike the identical properties (except for optical rotation) observed in enantiomers.[36] A classic example of diastereomers is found in tartaric acid, where the (2R,3R)-tartaric acid and the meso form (2R,3S)-tartaric acid differ in configuration at one chiral center.[34] The meso form, being achiral due to an internal plane of symmetry, exhibits different solubility in water compared to the chiral (2R,3R) form; for instance, the meso isomer has lower solubility (125 g/100 mL) compared to the chiral form (135 g/100 mL), allowing separation via fractional crystallization.[37] This difference in properties highlights how diastereomers can be resolved using conventional techniques like chromatography or distillation, in contrast to enantiomers which require specialized methods such as chiral resolution agents.[38] Diastereomers require the presence of multiple stereogenic centers or other elements of chirality to exist, as a single chiral center can only produce enantiomers.[35] The term encompasses a broader range of stereoisomers than just those from chiral centers, including geometric isomers arising from restricted rotation, though the focus here is on chiral variants.[39] A specific subtype of diastereomers is epimers, which are stereoisomers that differ in configuration at only one chiral center while maintaining the same configuration at all others.[40] Epimers are particularly relevant in carbohydrate chemistry, where they influence biological recognition and reactivity.[41]Geometric Isomers

Geometric isomers, also referred to as cis-trans isomers, are stereoisomers that result from the restricted rotation about a bond, typically a carbon-carbon double bond in alkenes or within cyclic structures like cycloalkanes, leading to distinct spatial arrangements of substituents.[42] This form of isomerism is a subtype of diastereomerism, where the isomers are not mirror images.[43] In alkenes, the rigidity of the double bond prevents rotation, allowing for two configurations when each carbon of the double bond is attached to two different substituents: the cis isomer, in which the higher-priority substituents (or similar groups) are on the same side of the double bond, and the trans isomer, in which they are on opposite sides.[42] A classic example is 2-butene (CH₃-CH=CH-CH₃), where cis-2-butene has both methyl groups on the same side and a boiling point of 3.7 °C, while trans-2-butene has them on opposite sides with a boiling point of 0.9 °C; the difference arises from the greater dipole moment in the cis form, enhancing intermolecular forces./10:_Alkenes/10.04:_Physical_Properties) Cis-2-butene: Trans-2-butene:

CH3 CH3

| \

H-C=C-H H-C=C-H

| /

CH3 CH3

Cis-2-butene: Trans-2-butene:

CH3 CH3

| \

H-C=C-H H-C=C-H

| /

CH3 CH3

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {C} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{8}}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c41f8d557f0a16aa1dd809d618dbbe7cf1729c1)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {C} {-}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{-}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {OH} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d4c1afb5919de9c5e518068570204cfefae7675)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {C} {-}\mathrm {CH} (\mathrm {OH} ){-}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e6d4babdd48d017f53a22e9db02c770baedd7f1d)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {C} {-}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{-}\mathrm {O} {-}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e22802c7812dc66a3f2429a9c666294d15ad9a41)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {C} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e88ccb88e7aad14abce97dc1efee289f5d17c7fc)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {ClF} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2ca770cb7e661151541f802b072d03d313d86fe)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {C} {-}\mathrm {CH} {=}\mathrm {C} {=}\mathrm {CH} {-}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0b64d5144149f29e3b17437b9bc92d844ad2729e)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {C} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {Cl} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/367dd6b1bb00f7135a2a4ce25db1f3b87474e138)

![{\displaystyle {(\mathrm {CHOH} ){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{6}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d8ed84eecaa77b0cdea3c27a7c3f4383126708e6)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {MX} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {Y} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/89d6b04beb0aff0255d060dcfe82b94e7eb17930)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {MX} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}\mathrm {Y} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fbc05157241b10a16716bf12ad33392324c6de05)

![{\displaystyle {{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {1}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {1}}}\mathrm {H} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f14898bb2934c97f9d6fb37be91eeef9160dde7d)

![{\displaystyle {{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/059d80356842d64716ca8b5dded6cb0574a06b5f)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {HD} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {C} {-}\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c7155c920e0b89388c5fff3b60b12cbc315f54fc)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {DH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {C} {-}\mathrm {CDH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6c0c0b067ab6aec66bd5efd83f67805e7819b749)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {C} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{5}}\mathrm {D} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/34c47a66e1c562f92821def524cf617c65ec3692)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {C} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}\mathrm {D} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3a063eb275e2950a611768d688ced2e3caa86fed)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {CH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}\mathrm {N} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/94148b7489da7e1cf51c51c2ef5b47cc11444208)

![{\displaystyle {(\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {N} {-}){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {C} {=}\mathrm {O} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4855aa3ee05f54745c3fe82fb3139e4d8a447fcc)

![{\displaystyle {[\mathrm {NH} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{4}}^{+}]~[\mathrm {O} {=}\mathrm {C} {=}\mathrm {N} {\vphantom {A}}^{-}]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d88ac58af5dbab726d06cd37724e55e9cac30ba)