Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

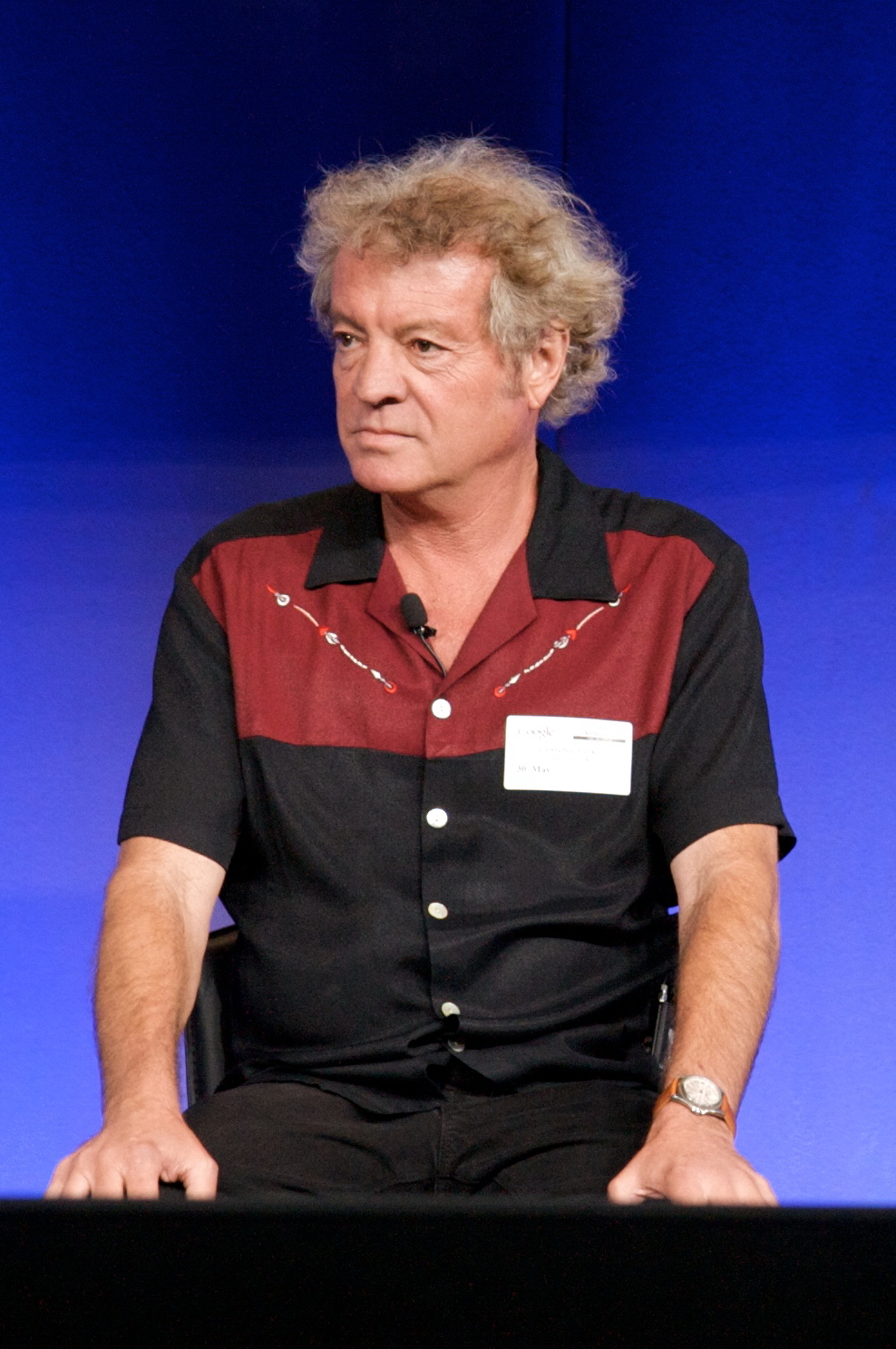

Lawrence Lasker

View on Wikipedia

Lawrence Charles Lasker (born October 7, 1949) is an American screenwriter and producer who entered American film in 1983 as writer of the movie WarGames.[1][2]

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Lasker was born in Los Angeles County, California. He is the son of actor Jane Greer and producer Edward Lasker.[3] His paternal grandfather was businessman Albert Lasker and his paternal step-grandmothers were actor Doris Kenyon and Mary Woodard Lasker. He graduated from the Phillips Exeter Academy in 1967 and attended Yale University, as did his father.

Filmography

[edit]| Title | Year | Producer | Writer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WarGames | 1983 | Yes | ||

| Project X | 1987 | Yes | Story | |

| True Believer | 1989 | Yes | ||

| Awakenings | 1990 | Yes | ||

| Eddie Dodd | 1991 | Executive | Creator | Television series (6 episodes) |

| Sneakers | 1992 | Yes | Yes |

Also cameo as "Party Guest" in The Other Side of the Wind (2018).

Work nominated for awards

[edit]Lasker and Walter F. Parkes were nominated for an Academy Award in screenwriting in 1983 for WarGames.[4] Parkes and he later were nominated for Best Picture of the Year in 1990 for Awakenings. In 2023, Lasker won the Future of Life Award for reducing the risk of nuclear war through the power of storytelling.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Brown, Scott (July 21, 2008). "WarGames: A Look Back at the Film That Turned Geeks and Phreaks Into Stars". Wired.

- ^ "Lawrence Lasker". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Oliver, Myrna (August 28, 2001). "From the Archives: Jane Greer; Star of Film Noir 'Out of the Past'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Jackson, Matthew (June 1, 2018). "15 Surprising Facts About WarGames". Mental Floss.

- ^ "Future Of Life Award 2023". Future of Life Institute. Retrieved August 20, 2024.