Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Literary magazine

View on Wikipedia

A literary magazine is a periodical devoted to literature in a broad sense. Literary magazines usually publish short stories, poetry, and essays, along with literary criticism, book reviews, biographical profiles of authors, interviews and letters. Literary magazines are often called literary journals, or little magazines, terms intended to contrast them with larger, commercial magazines.[1]

History

[edit]Nouvelles de la république des lettres is regarded as the first literary magazine; it was established by Pierre Bayle in France in 1684.[2] Literary magazines became common in the early part of the 19th century, mirroring an overall rise in the number of books, magazines, and scholarly journals being published at that time. In Great Britain, critics Francis Jeffrey, Henry Brougham and Sydney Smith founded the Edinburgh Review in 1802. Other British reviews of this period included the Westminster Review (1824), The Spectator (1828), and Athenaeum (1828). In the United States, early journals included the Philadelphia Literary Magazine (1803–1808), the Monthly Anthology (1803–11), which became the North American Review, the Yale Review (founded in 1819), The Yankee (1828–1829) The Knickerbocker (1833–1865), Dial (1840–44) and the New Orleans–based De Bow's Review (1846–80). Several prominent literary magazines were published in Charleston, South Carolina, including The Southern Review (1828–32) and Russell's Magazine (1857–60).[3] The most prominent Canadian literary magazine of the 19th century was the Montreal-based Literary Garland.[4]

The North American Review, founded in 1815, is the oldest American literary magazine. However, it had its publication suspended during World War II, and the Yale Review (founded in 1819) did not; thus the Yale journal is the oldest literary magazine in continuous publication. Begun in 1889, Poet Lore is considered the oldest journal dedicated to poetry.[5] By the end of the century, literary magazines had become an important feature of intellectual life in many parts of the world. One of the most notable 19th century literary magazines of the Arabic-speaking world was Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa.[6]

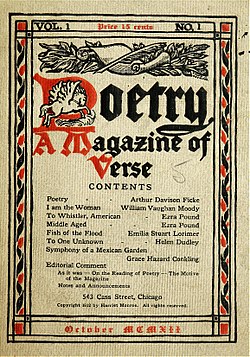

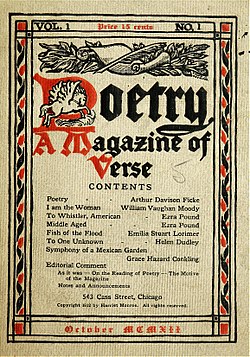

Among the literary magazines that began in the early part of the 20th century is Poetry magazine. Founded in 1912, it published T. S. Eliot's first poem, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock". Another was The Bellman, which began publishing in 1906 and ended in 1919, was edited by William Crowell Edgar and was based in Minneapolis, Minnesota.[7] Other important early-20th century literary magazines include The Times Literary Supplement (1902), Southwest Review (1915), Virginia Quarterly Review (1925), World Literature Today (founded in 1927 as Books Abroad before assuming its present name in 1977), Southern Review (1935), and New Letters (1935). The Sewanee Review, although founded in 1892, achieved prominence largely thanks to Allen Tate, who became editor in 1944.[8]

Two of the most influential—though radically different—journals of the last half of the 20th century were The Kenyon Review (KR) and the Partisan Review. The Kenyon Review, edited by John Crowe Ransom, espoused the so-called New Criticism. Its platform was avowedly unpolitical. Although Ransom came from the South and published authors from that region, KR also published many New York–based and international authors. The Partisan Review was first associated with the American Communist Party and the John Reed Club; however, it soon broke ranks with the party. Nevertheless, politics remained central to its character, while it also published significant literature and criticism.

The middle-20th century saw a boom in the number of literary magazines, which corresponded with the rise of the small press. Among the important journals which began in this period were Nimbus: A Magazine of Literature, the Arts, and New Ideas, which began publication in 1951 in England, the Paris Review, which was founded in 1953, The Massachusetts Review and Poetry Northwest, which were founded in 1959, X Magazine, which ran from 1959 to 1962, and the Denver Quarterly, which began in 1965. The 1970s saw another surge in the number of literary magazines, with a number of distinguished journals getting their start during this decade, including Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, Ploughshares, The Iowa Review, Granta, Agni, The Missouri Review, and New England Review. Other highly regarded print magazines of recent years include The Threepenny Review, The Georgia Review, Ascent, Shenandoah, The Greensboro Review, ZYZZYVA, Glimmer Train, Tin House, Half Mystic Journal, the Canadian magazine Brick, the Australian magazine HEAT, and Zoetrope: All-Story. Some short fiction writers, such as Steve Almond, Jacob M. Appel and Stephen Dixon have built national reputations in the United States primarily through publication in literary magazines.[citation needed]

The Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publishers (COSMEP) was founded by Richard Morris in 1968. It was an attempt to organize the energy of the small presses. Len Fulton, editor and founder of Dustbook Publishing, assembled and published the first real list of these small magazines and their editors in the mid-1970s. This made it possible for poets to pick and choose the publications most amenable to their work and the vitality of these independent publishers was recognized by the larger community, including the National Endowment for the Arts, which created a committee to distribute support money for this burgeoning group of publishers called the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines (CCLM). This organisation evolved into the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP).

Many prestigious awards exist for works published in literary magazines including the Pushcart Prize and the O. Henry Awards. Literary magazines also provide many of the pieces in The Best American Short Stories and The Best American Essays annual volumes.

Argentine literary magazines tradition

[edit]

In Argentina, literary magazines were profoundly impactful in the social and political discussions all throughout its history. The first literary magazine in Argentina was La Aljaba, created in 1830, which was also one of the first magazines directed by women and for women in the world.[9] In 1837, Juan Bautista Alberdi, the main thinker behind the Constitution of Argentina, created his literary magazine, La Moda. Several members of the 1837 Generation, (which was the movement that brought new artistic tendencies from Europe such as Romanticism and political liberalism to Argentina), published their writings in it.

In 1924, Modernist writers created Martín Fierro (named after José Hernandez's epic poem), it was key for the development of the Argentine avant-garde, greatly influenced by ultraism. Many of the most important writers of the early 20th century in Argentina published their writings in Martín Fierro, such as Oliverio Girondo, Victoria Ocampo, Ricardo Güiraldes, Leopoldo Marechal, and most importantly, Jorge Luis Borges.[10] In 1931, The former members of Martín Fierro created Sur, the most relevant Argentine authors published their writings there, such as Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Ernesto Sábato, but also prominent writers from other countries, such as Gabriel García Márquez, Pablo Neruda and Octavio Paz. The Sur magazine shared the same artistic values of its predecessor, and was more relevant politically, being strongly opposed to Peronism and Nazism. Many of the best stories by Borges, such as El Aleph, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius and The Circular Ruins, were originally published in Sur.

In 1953, Ismael Viñas created Contorno, a disruptive magazine affiliated with communism and existentialism, in which writer David Viñas, sociologist Juan José Sebreli and philosopher León Rozitchner, among others, published their writings.

In 1988 Babel. Revista de libros was created by Martín Caparrós and Jorge Dorio. it sought to recover diverse literary voices and push experimental forms after the last Argentine dictatorship.

In the 21st century, while print magazines have declined, online literary magazines, such as Revista Ñ thrive.

Online literary magazines

[edit]SwiftCurrent, created in 1984, was the first online literary magazine. It functioned as more of a database of literary works than a literary publication.[11] In 1995, the Mississippi Review was the first large literary magazine to launch a fully online issue.[12] By 1998, Fence and Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern were published and quickly gained an audience.[13] Around 1996, literary magazines began to appear more regularly online. At first, some writers and readers dismissed online literary magazines as not equal in quality or prestige to their print counterparts, while others said that these were not properly magazines and were instead ezines. Since then, though, many writers and readers have accepted online literary magazines as another step in the evolution of independent literary journals.

There are thousands of other online literary publications and it is difficult to judge the quality and overall impact of this relatively new publishing medium.[14]

Little magazines

[edit]Little magazines, or "small magazines", are literary magazines that often publish experimental literature and the non-conformist writings of relatively unknown writers. Typically they had small readership, were financially uncertain or non-commercial, were irregularly published and showcased artistic innovation.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cowley, Malcolm (September 14, 1947). "The Little Magazines Growing Up; The Little Magazines". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- ^ Travis Kurowski (Fall 2008). "Some Notes on the History of the Literary Magazine". Mississippi Review. 36 (3): 231–243. JSTOR 20132855.

- ^ "Library of Southern Literature: Antebellum Era". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- ^ MacGillivray, S. R. (1997). "Literary Garland, The". The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature. William Toye, Eugene Benson (2nd ed.). Toronto: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-541167-6. OCLC 39624837.

- ^ Charles, Ron. "America's oldest poetry journal celebrates 125 years of great verse". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- ^ "Urwa al-Wuthqa, al- | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- ^ "The Bellman". Onlinebooks. John Mark Ockerbloom. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ History Archived 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "La Aljaba – Ahira" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "Martín Fierro – Ahira" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "SwiftCurrent". www2.iath.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ^ "Volume 1, Number 1, April 1995". The Mississippi Review. University of Southern Mississippi. Archived from the original on 1998-01-28. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Kurowski, Travis (2008). "Some Notes on the History of the Literary Magazine". Mississippi Review. 36 (3): 231–243. JSTOR 20132855.

- ^ "Technology, Genres, and Value Change:the Case of Literary Magazines" by S. Pauling and M. Nilan. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57(7):662-672 doi10.1022/asi.20345

- ^ Barsanti, Michael (July 2017). "Little Magazines". Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Literature. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.588. ISBN 978-0-19-020109-8. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Brooker, Peter; Thacker, Andrew. "The Oxford critical and cultural history of modernist magazines, Volume One: Britain and Ireland 1880–1955". Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921115-9.

External links

[edit]- Council of Literary Magazines and Small Presses

- The Little Magazine a Hundred Years On A Reader's Report by Steve Evans

- Little Magazine Interview Index Housed at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Special Collections, the Little Magazine Collection, one of the most extensive of its kind in the United States, includes approximately 7,000 English-language literary magazines published in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and Australia/New Zealand, mostly in the 20th century.

- Little Magazine Collection Blog Housed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

- NewPages Guide to Literary Magazines in Print and Online.

- Poets & Writers Literary Magazine Database

- EWR: Literary Magazines Searchable listing of Literary Magazines

Literary magazine

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Elements and Purpose

Literary magazines constitute periodicals dedicated to the dissemination of original literary works, encompassing poetry, short fiction, essays, creative nonfiction, and literary criticism, alongside occasional inclusions of visual art or photography. These publications prioritize content that foregrounds linguistic precision, introspective narratives, and innovative forms, often amplifying voices and styles overlooked by commercial outlets. Unlike mass-market periodicals, their editorial selections emphasize artistic integrity and intellectual depth, with issues typically released on quarterly, biannual, or annual schedules through small presses, university affiliations, or independent operations.[8][9] The fundamental purpose of literary magazines lies in fostering literary development by offering a venue for writers to refine their craft, gain visibility among discerning readers, and build professional credentials essential for broader recognition, such as book deals or awards. By operating on mission-driven principles rather than profit motives, they sustain a space for experimental, niche, or politically incisive material that challenges prevailing cultural norms, thereby preserving diverse literary traditions as historical records of societal shifts. This non-commercial ethos, evident in their low circulation and frequent reliance on subscriptions, grants, or fees, underscores their role in cultivating a dedicated community of creators and critics committed to elevating literary standards over popular consumption.[8][9]Distinctions from Broader Periodicals

Literary magazines differ from broader periodicals, such as general interest or news-oriented publications, in their exclusive focus on original literary content including short fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction, and literary criticism, rather than journalistic reporting, lifestyle features, or topical essays designed for mass consumption.[10] This emphasis stems from a commitment to artistic expression and experimentation, often prioritizing unpublished works from emerging or avant-garde authors over content vetted for broad commercial appeal.[11] In terms of editorial processes, literary magazines frequently solicit and review unsolicited submissions based on literary merit and innovation, contrasting with the commissioned, deadline-driven articles in mainstream magazines that align with market trends or advertiser interests.[12] This approach enables the publication of boundary-pushing material that may challenge conventional tastes, unhindered by the profitability demands that shape content in larger periodicals.[13] Economically, literary magazines operate predominantly as non-commercial ventures with small print runs—often under 5,000 copies—and sustain themselves through subscriptions, donations, university affiliations, or literary grants, eschewing heavy reliance on advertising revenue that dominates broader periodicals.[14] Their precarious financial models, marked by frequent short lifespans, underscore a dedication to cultural rather than profit-driven goals, unlike the stable, ad-supported operations of commercial magazines targeting millions of readers.[12] Audience composition further delineates the two: literary magazines cultivate niche communities of writers, academics, and dedicated readers seeking depth and discovery, whereas broader periodicals aim for heterogeneous general publics through accessible, entertaining formats with glossy production and frequent issues.[10] This divergence fosters literary magazines' role as incubators for new movements, free from the homogenizing pressures of mass-market viability.[13]Historical Development

Origins in Early Print Culture (18th–Mid-19th Century)

The periodical essay emerged in early 18th-century Britain as a foundational form for literary magazines, driven by expanding print culture, coffeehouse sociability, and a burgeoning market for instructive yet entertaining prose. Richard Steele's The Tatler (1709–1711), published thrice weekly for 271 issues, introduced serialized essays on manners, literature, and contemporary life, often under pseudonyms like Isaac Bickerstaff, targeting an urban readership seeking moral guidance amid social flux.[15] This format blended news commentary with literary reflection, capitalizing on improved printing techniques and literacy rates that approached 60% among men in England by 1710.[16] Joseph Addison and Steele's The Spectator (1711–1712), issued daily for 555 numbers, refined and popularized the genre, achieving circulations of 3,000–4,000 copies per issue through subscriptions and shared readings in public venues.[17] Essays covered literary criticism, poetry analysis, and fictional narratives, such as Addison's pieces on Milton's Paradise Lost, fostering a taste for aesthetic discourse while avoiding overt partisanship to broaden appeal.[18] Samuel Johnson's The Rambler (1750–1752), with 208 twice-weekly issues, shifted toward denser moral and philosophical essays, including literary evaluations that professionalized criticism for an educated elite.[19] These publications, reprinted in collected volumes selling thousands of copies, established the periodical as a vehicle for original literary content and debate, distinct from news sheets by prioritizing wit, character sketches, and cultural commentary. By the late 18th century, dedicated literary review periodicals supplanted pure essay serials, systematizing book assessments amid a flood of publications—over 2,000 new titles annually in Britain by 1790. Ralph Griffiths's Monthly Review (1749–1845), the first to offer comprehensive, signed critiques of contemporary works, ran for nearly a century and shaped authorial reputations through detailed analyses of novels, poetry, and scholarship.[20] Its rival, Critical Review (1756–1817), provided contrasting Tory perspectives, intensifying competitive scrutiny that elevated literary standards but often reflected ideological biases.[21] Into the early 19th century, quarterly reviews like the Edinburgh Review (1802–1929), founded by Francis Jeffrey and Sydney Smith, marked a maturation, blending incisive literary judgments with political essays to reach 9,000–13,000 subscribers by the 1810s.[22] This Whig-leaning outlet critiqued Romantic poets like Wordsworth harshly, influencing canon formation through authoritative, anonymous reviews that treated literature as a public concern. Monthly formats followed, such as Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine (1817 onward), which serialized fiction and poetry alongside reviews, adapting to cheaper paper production and steam presses that reduced costs by 50% post-1815.[23] In America, Joseph Dennie’s Port Folio (1801–1827) emulated British models with essays and criticism, while the North American Review (1815–1940) introduced quarterly rigor, reflecting transatlantic exchange amid growing national literatures. These developments, sustained by advertising revenue and middle-class subscriptions, embedded literary magazines in cultural discourse until mid-century expansions in serialization and illustration.[15]Rise of Modernist Little Magazines (Late 19th–Mid-20th Century)

The emergence of modernist little magazines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries responded to the limitations of commercial publishing, which favored conventional narratives and avoided experimental forms amid rapid industrialization and cultural shifts. These periodicals, often self-financed or patron-supported with circulations under 1,000 copies, prioritized artistic innovation over profit, publishing avant-garde poetry, prose, and manifestos that challenged Victorian sensibilities. Precursors appeared in fin-de-siècle Europe and America, such as Vance Thompson's M'lle New York launched in August 1895, which championed Decadent and Symbolist influences from French writers, fostering a transatlantic exchange that laid groundwork for modernism.[24] In the United States, Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, founded by Harriet Monroe in October 1912 in Chicago with pledges from 100 local subscribers totaling $5,000 annually, marked a pivotal moment by establishing an "Open Door" policy for unsolicited submissions and emphasizing American verse alongside international voices. Ezra Pound, appointed foreign correspondent, used the magazine to promote Imagism and debuted T.S. Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" in the June 1915 issue, signaling a break from traditional metrics. Similarly, Margaret Anderson's The Little Review, initiated in March 1914 in Chicago's Fine Arts Building, embraced anarchism and modernism, serializing James Joyce's Ulysses from March 1918 to December 1920, which prompted U.S. Post Office seizures and an obscenity conviction in 1921 against editors Anderson and Jane Heap.[25][26][27] British counterparts amplified this trend: The Egoist, evolving from Dora Marsden's feminist New Freewoman and relaunched in January 1914 under Harriet Shaw Weaver's editorship from 1916, serialized Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1914–1915) and printed early criticism by Pound and Eliot, achieving modest sales of around 400 copies per issue. Wyndham Lewis's BLAST, issuing its first number on 20 June 1914 just before World War I, co-edited with Pound, declared Vorticism's "great English vortex" through explosive manifestos rejecting Futurism while celebrating angular, machine-age aesthetics; a second war-interrupted issue followed in July 1915. These outlets, despite ephemeral runs—BLAST ceased after two issues—facilitated cross-pollination among expatriate networks, enabling canonical works' initial dissemination and movements' coalescence amid wartime disruptions and censorship pressures.[28][29][30] By the interwar period through the mid-20th century, little magazines like Eugene Jolas's transition (1927–1938) in Paris extended this legacy, publishing Beckett, Hemingway, and surrealists, while sustaining modernism's emphasis on fragmentation and subjectivity against rising mass culture. Their non-commercial ethos, reliant on editorial zeal and subsidies, contrasted with mainstream journals' advertiser-driven conservatism, proving instrumental in canonizing figures like Joyce, Pound, and Eliot despite financial precarity and legal hurdles.[31]Postwar Expansion and Institutionalization (Mid-20th Century–1990s)

Following World War II, literary magazines experienced significant expansion, particularly in the United States and Western Europe, as postwar economic recovery, rising literacy rates, and expanded higher education access—fueled by initiatives like the U.S. GI Bill—created demand for outlets publishing emerging writers and experimental work.[32] This period marked a shift from the avant-garde "little magazines" of modernism to a broader ecosystem, including university-sponsored journals that provided institutional stability amid fluctuating private funding.[33] By the 1950s, notable examples included the Paris Review (founded 1953), which emphasized fiction and interviews, and the Hudson Review (1947), focusing on criticism and poetry.[32] Institutionalization accelerated in the 1960s through government and academic support structures. The U.S. National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), established in 1965, began channeling federal funds to literary periodicals via regranting programs, enabling sustainability for non-commercial outlets.[34] In 1967, the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines (CCLM, later CLMP in 1990) formed under NEA auspices to coordinate resources, advocacy, and directories for over 1,000 independent journals by the 1970s, professionalizing operations and fostering networks.[35] Concurrently, the proliferation of Master of Fine Arts (MFA) programs at universities—growing from fewer than 20 in 1960 to over 100 by 1990—spurred campus-based magazines like Ploughshares (1971) at Emerson College and TriQuarterly at Northwestern (1964), which integrated literary publishing into academic curricula.[33] Technological and cultural shifts further drove growth into the 1990s. The "mimeograph revolution" of the 1960s onward democratized production, enabling small-scale runs of thousands of titles annually, often tied to countercultural movements, with estimates of 3,000–5,000 U.S. little magazines active by the late 1970s, many short-lived but influential in launching authors like Raymond Carver.[36][33] In Europe, journals like France's Les Temps Modernes (1945) institutionalized intellectual discourse, while U.K. publications such as Encounter (1953) received foundation backing, blending literary and political content.[32] By the 1990s, this era's legacy included diversified formats and a reliance on grants, university affiliations, and endowments, though many faced ongoing viability challenges from limited circulation (often under 5,000 copies per issue).[36] This institutional framework preserved literary innovation but increasingly aligned magazines with academic and funding priorities, reducing some of the prewar era's radical autonomy.[33]Types and Formats

Little Magazines and Experimental Outlets

Little magazines represent a category of literary periodicals characterized by their small circulation, limited financial resources, and commitment to publishing avant-garde, experimental, or otherwise marginalized literary works that commercial outlets typically reject due to perceived lack of mass appeal. These publications often feature poetry, short fiction, and essays emphasizing formal innovation, unconventional themes, or dissenting voices, operating independently from advertising revenue or large distribution networks. Founded by editors driven by ideological or artistic passion rather than profit, little magazines historically endure short lifespans—many lasting only a few issues—yet serve as incubators for literary movements by providing space for unpublished authors and radical aesthetics.[37][38] Experimental outlets, a subset or close analog to little magazines, extend this model by prioritizing boundary-pushing content such as surrealist manifestos, dadaist collages, or stream-of-consciousness prose, often integrating visual arts, manifestos, or interdisciplinary experiments that challenge traditional narrative structures. Unlike broader literary journals, these outlets eschew polished, market-friendly submissions in favor of raw, provocative material that tests the limits of language and form, frequently aligning with countercultural or anti-establishment sentiments. Their editorial processes emphasize curatorial risk-taking, with selections guided by a rejection of bourgeois norms rather than reader polls or sales projections, resulting in outputs that prioritize cultural disruption over accessibility.[39][31] In the early 20th century, little magazines and experimental outlets played a pivotal role in disseminating modernism, serving as primary venues for poets and writers during periods like the interwar years when mainstream presses favored conventional fare. For instance, Poetry magazine, launched in Chicago in October 1912 by Harriet Monroe, introduced American audiences to imagist and modernist verse, including T.S. Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" in its June 1915 issue, which had been declined by several larger periodicals. Similarly, European counterparts like transition (1927–1938), edited by Eugene Jolas, serialized James Joyce's Work in Progress (later Finnegans Wake) and championed multilingual experimentation, fostering transatlantic networks of avant-garde writers. These outlets numbered in the thousands by the 1920s, with over 1,000 active in the U.S. alone during the modernist peak, enabling movements like dada and surrealism to gain traction despite initial obscurity.[40][41] Post-World War II, experimental outlets evolved to include Beat Generation zines and underground presses, such as Big Table (1959–1961), which reprinted material censored from the Chicago Review for obscenity, featuring William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch excerpts and defending literary freedom against legal challenges. In non-Western contexts, Indian little magazines like Krittibas (1953–present) in Bengali promoted regional modernism against colonial legacies, publishing poets who blended indigenous forms with Western influences. Despite their ephemerality—evidenced by high failure rates, with many ceasing after 2–5 years due to funding shortages—these formats have sustained literary vitality by democratizing access for underrepresented voices, though their influence wanes in digital eras dominated by algorithmic curation.[42][43]Mainstream and Scholarly Literary Journals

Mainstream literary journals represent established periodicals that prioritize the publication of original creative works, including short fiction, poetry, and personal essays, targeting a readership that extends beyond academic specialists to include general literary enthusiasts. These outlets often balance accessibility with literary quality, featuring contributions from both novice and renowned authors, and may incorporate supplementary elements such as author interviews or brief reviews to contextualize the primary material. Funding typically derives from subscriptions, endowments, or foundation grants, enabling relatively stable operations and circulations in the tens of thousands for flagship titles. Unlike experimental little magazines, mainstream journals tend to favor polished, narrative-driven pieces that align with conventional literary standards while occasionally introducing innovative voices.[44][45] Poetry, founded in 1912 by Harriet Monroe in Chicago, exemplifies this category as the oldest continuously published monthly journal dedicated to verse in the English-speaking world, having printed approximately 300 poems annually from tens of thousands of submissions as of the early 2000s.[25] [46] The Paris Review, established in 1953 by Peter Matthiessen and others in Paris before relocating to New York, has distinguished itself through long-form interviews with prominent writers—totaling over 80 by the 2010s—and by launching careers of authors like Jack Kerouac and Philip Roth via its fiction and poetry selections.[47] Other enduring examples include Ploughshares, founded in 1971 by Emerson College and known for themed issues curated by guest editors, and The Virginia Quarterly Review, revived in 2001 after a hiatus and praised for its eclectic mix of genres under nonprofit auspices.[45] Scholarly literary journals, by contrast, function as peer-reviewed venues for advancing academic inquiry into literature, publishing analytical essays, theoretical frameworks, and historical interpretations that undergo rigorous evaluation by domain experts prior to acceptance. These publications cater primarily to researchers, professors, and graduate students, emphasizing methodological precision, archival evidence, and engagement with existing scholarship over creative output, with articles often cited in subsequent studies to build cumulative knowledge. Circulation is generally lower and tied to professional associations or university presses, prioritizing depth and influence within specialized fields rather than broad appeal. Peer review processes, typically double-blind, mitigate subjective biases but can extend timelines to 6-12 months or more.[48][49] Prominent instances include PMLA (Publications of the Modern Language Association), launched in 1884 as the flagship journal of the MLA, which disseminates essays on language and literature deemed broadly relevant to over 20,000 members, fostering debates on canon formation and interpretive methodologies.[50] ELH (English Literary History), originating in 1934 at Johns Hopkins University, specializes in criticism of British and American literature from the Renaissance onward, with issues aggregating 4-6 articles per quarterly volume.[51] Additional key titles encompass American Literary History, which since 1989 has interrogated U.S. literary traditions through interdisciplinary lenses, and Contemporary Literature, a University of Wisconsin quarterly since 1960 that profiles modern authors via criticism and interviews.[49] These journals collectively underpin tenure-track evaluations and shape pedagogical curricula, though their selection processes have drawn scrutiny for favoring conformist viewpoints amid institutional ideological homogeneity in humanities departments.[52]