Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Macromolecule

View on Wikipedia

A macromolecule is a "molecule of high relative molecular mass, the structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass."[1] Polymers are physical examples of macromolecules. Common macromolecules are biopolymers (nucleic acids, proteins, and carbohydrates),[2] polyolefins (polyethylene) and polyamides (nylon).

Synthetic macromolecules

[edit]

Many macromolecules are synthetic polymers (plastics, synthetic fibers, and synthetic rubber). Polyethylene is produced on a particularly large scale such that ethylene is the primary product in the chemical industry.[3]

Macromolecules in nature

[edit]- Proteins are polymers of amino acids joined by peptide bonds. [citation needed]

- DNA and RNA are polymers of nucleotides joined by phosphodiester bonds. These nucleotides consist of a phosphate group, a sugar (ribose in the case of RNA, deoxyribose in the case of DNA), and a nucleotide base (either adenine, guanine, thymine, uracil, or cytosine, where thymine occurs only in DNA and uracil only in RNA). [citation needed]

- Polysaccharides (such as starch, cellulose, and chitin) are polymers of monosaccharides joined by glycosidic bonds. [citation needed]

- Some lipids (organic nonpolar molecules) are macromolecules, with a variety of different structures. [citation needed]

Linear biopolymers

[edit]All living organisms are dependent on three essential biopolymers for their biological functions: DNA, RNA and proteins.[4] Each of these molecules is required for life since each plays a distinct, indispensable role in the cell.[5] The simple summary is that DNA makes RNA, and then RNA makes proteins.

DNA, RNA, and proteins all consist of a repeating structure of related building blocks (nucleotides in the case of DNA and RNA, amino acids in the case of proteins). In general, they are all unbranched polymers, and so can be represented in the form of a string. Indeed, they can be viewed as a string of beads, with each bead representing a single nucleotide or amino acid monomer linked together through covalent chemical bonds into a very long chain. [citation needed]

In most cases, the monomers within the chain have a strong propensity to interact with other amino acids or nucleotides. In DNA and RNA, this can take the form of Watson–Crick base pairs (G–C and A–T or A–U), although many more complicated interactions can and do occur. [citation needed]

Structural features

[edit]| DNA | RNA | Proteins | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encodes genetic information | Yes | Yes | No |

| Catalyzes biological reactions | No | Yes | Yes |

| Building blocks (type) | Nucleotides | Nucleotides | Amino acids |

| Building blocks (number) | 4 | 4 | 20 |

| Strandedness | Double | Single | Single |

| Structure | Double helix | Complex | Complex |

| Stability to degradation | High | Variable | Variable |

| Repair systems | Yes | No | No |

Because of the double-stranded nature of DNA, essentially all of the nucleotides take the form of Watson–Crick base pairs between nucleotides on the two complementary strands of the double helix. [citation needed]

In contrast, both RNA and proteins are normally single-stranded. Therefore, they are not constrained by the regular geometry of the DNA double helix, and so fold into complex three-dimensional shapes dependent on their sequence. These different shapes are responsible for many of the common properties of RNA and proteins, including the formation of specific binding pockets, and the ability to catalyse biochemical reactions.

DNA is optimised for encoding information

[edit]DNA is an information storage macromolecule that encodes the complete set of instructions (the genome) that are required to assemble, maintain, and reproduce every living organism.[6]

DNA and RNA are both capable of encoding genetic information, because there are biochemical mechanisms which read the information coded within a DNA or RNA sequence and use it to generate a specified protein. On the other hand, the sequence information of a protein molecule is not used by cells to functionally encode genetic information.[2]: 5

DNA has three primary attributes that allow it to be far better than RNA at encoding genetic information. First, it is normally double-stranded, so that there are a minimum of two copies of the information encoding each gene in every cell. Second, DNA has a much greater stability against breakdown than does RNA, an attribute primarily associated with the absence of the 2'-hydroxyl group within every nucleotide of DNA. Third, highly sophisticated DNA surveillance and repair systems are present which monitor damage to the DNA and repair the sequence when necessary. Analogous systems have not evolved for repairing damaged RNA molecules. Consequently, chromosomes can contain many billions of atoms, arranged in a specific chemical structure. [citation needed]

Proteins are optimised for catalysis

[edit]Proteins are functional macromolecules responsible for catalysing the biochemical reactions that sustain life.[2]: 3 Proteins carry out all functions of an organism, for example photosynthesis, neural function, vision, and movement.[7]

The single-stranded nature of protein molecules, together with their composition of 20 or more different amino acid building blocks, allows them to fold in to a vast number of different three-dimensional shapes, while providing binding pockets through which they can specifically interact with all manner of molecules. In addition, the chemical diversity of the different amino acids, together with different chemical environments afforded by local 3D structure, enables many proteins to act as enzymes, catalyzing a wide range of specific biochemical transformations within cells. In addition, proteins have evolved the ability to bind a wide range of cofactors and coenzymes, smaller molecules that can endow the protein with specific activities beyond those associated with the polypeptide chain alone. [citation needed]

RNA is multifunctional

[edit]RNA is multifunctional, its primary function is to encode proteins, according to the instructions within a cell's DNA.[2]: 5 They control and regulate many aspects of protein synthesis in eukaryotes. [citation needed]

RNA encodes genetic information that can be translated into the amino acid sequence of proteins, as evidenced by the messenger RNA molecules present within every cell, and the RNA genomes of a large number of viruses. The single-stranded nature of RNA, together with tendency for rapid breakdown and a lack of repair systems means that RNA is not so well suited for the long-term storage of genetic information as is DNA. [citation needed]

In addition, RNA is a single-stranded polymer that can, like proteins, fold into a very large number of three-dimensional structures. Some of these structures provide binding sites for other molecules and chemically active centers that can catalyze specific chemical reactions on those bound molecules. The limited number of different building blocks of RNA (4 nucleotides vs >20 amino acids in proteins), together with their lack of chemical diversity, results in catalytic RNA (ribozymes) being generally less-effective catalysts than proteins for most biological reactions. [citation needed]

Branched biopolymers

[edit]

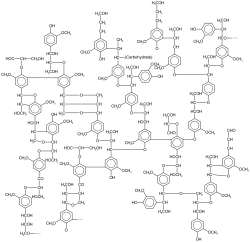

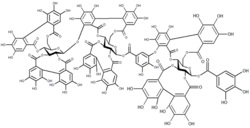

Lignin is a pervasive natural macromolecule. It comprises about a third of the mass of trees. lignin arises by crosslinking. Related to lignin are polyphenols, which consist of a branched structure of multiple phenolic subunits. They can perform structural roles (e.g. lignin) as well as roles as secondary metabolites involved in signalling, pigmentation and defense. [citation needed]

Carbohydrate macromolecules (polysaccharides) are formed from polymers of monosaccharides.[2]: 11 Because monosaccharides have multiple functional groups, polysaccharides can form linear polymers (e.g. cellulose) or complex branched structures (e.g. glycogen). Polysaccharides perform numerous roles in living organisms, acting as energy stores (e.g. starch) and as structural components (e.g. chitin in arthropods and fungi). Many carbohydrates contain modified monosaccharide units that have had functional groups replaced or removed. [citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Macromolecule (polymer molecule)". IUPAC Goldbook. doi:10.1351/goldbook.M03667.

- ^ a b c d e Stryer L, Berg JM, Tymoczko JL (2002). Biochemistry (5th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4955-4. Archived from the original on December 10, 2010.

- ^ Whiteley, Kenneth S.; Heggs, T. Geoffrey; Koch, Hartmut; Mawer, Ralph L.; Immel, Wolfgang (2000). "Polyolefins". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_487. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Berg, Jeremy Mark; Tymoczko, John L.; Stryer, Lubert (2010). Biochemistry, 7th ed. (Biochemistry (Berg)). W.H. Freeman & Company. ISBN 978-1-4292-2936-4. Fifth edition available online through the NCBI Bookshelf: link

- ^ Walter, Peter; Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander S.; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin C.; Roberts, Keith (2008). Molecular Biology of the Cell (5th edition, Extended version). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4111-6.. Fourth edition is available online through the NCBI Bookshelf: link

- ^ Golnick, Larry; Wheelis, Mark. (1991-08-14). The Cartoon Guide to Genetics. Collins Reference. ISBN 978-0-06-273099-2.

- ^ Takemura, Masaharu (2009). The Manga Guide to Molecular Biology. No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-59327-202-9.

- ^ Roland E. Bauer; Volker Enkelmann; Uwe M. Wiesler; Alexander J. Berresheim; Klaus Müllen (2002). "Single-Crystal Structures of Polyphenylene Dendrimers". Chemistry: A European Journal. 8 (17): 3858–3864. doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20020902)8:17<3858::AID-CHEM3858>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 12203280.

External links

[edit]- Synopsis of Chapter 5, Campbell & Reece, 2002

- Lecture notes on the structure and function of macromolecules Archived 2009-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Several (free) introductory macromolecule related internet-based courses Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Giant Molecules! by Ulysses Magee, ISSA Review Winter 2002–2003, ISSN 1540-9864. Cached HTML version of a missing PDF file. Retrieved March 10, 2010. The article is based on the book, Inventing Polymer Science: Staudinger, Carothers, and the Emergence of Macromolecular Chemistry by Yasu Furukawa.

Macromolecule

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Definition and Scope

A macromolecule is a molecule of high relative molecular mass, the structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass.[3] These units, known as monomers, are linked together primarily through covalent bonds to form long chains or networks, resulting in molecular weights typically ranging from a few thousand to several million daltons.[3] This repetitive assembly distinguishes macromolecules from smaller compounds and enables their role in diverse materials and biological systems. The concept of macromolecules emerged in the early 20th century through the work of German chemist Hermann Staudinger, who proposed in 1920 that substances like rubber consist of high-molecular-weight chains formed by polymerization of small molecules.[4] In 1922, Staudinger coined the term "macromolecules" to describe these large entities, both synthetic and natural, challenging prevailing views that attributed polymeric properties to associations of small molecules rather than covalent linkages.[4] His macromolecular hypothesis faced significant opposition but was ultimately validated, earning him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953 for establishing the foundations of macromolecular chemistry.[5] Unlike small molecules, which behave as discrete entities, the large size of macromolecules leads to unique collective behaviors, such as chain entanglement, where polymer chains interlock like spaghetti strands, influencing mechanical properties like elasticity and viscosity.[6] Common monomers include amino acids for proteins, nucleotides for nucleic acids, and monosaccharides for polysaccharides, illustrating the versatility of macromolecular construction across biological and synthetic contexts.[3]Molecular Structure and Bonding

Macromolecules are large molecules composed of repeating monomeric units linked primarily by strong covalent bonds that form the backbone of the polymer chain, defining its primary structure. This primary structure consists of a linear or branched sequence of monomers connected through specific covalent linkages, such as peptide bonds in proteins, where the carboxyl group of one amino acid reacts with the amino group of another to form an amide linkage via dehydration synthesis.[7] Similarly, in nucleic acids, phosphodiester bonds join nucleotides by linking the 5' phosphate group of one nucleotide to the 3' hydroxyl group of the next, creating a sugar-phosphate backbone essential for the molecule's integrity.[8] These covalent bonds provide the structural stability required for macromolecules to function as polymers, with the degree of polymerization calculated as , where is the number-average molecular weight of the polymer and is the molecular weight of the monomer unit. Beyond the primary structure, macromolecules adopt higher-order conformations through weaker non-covalent interactions that stabilize secondary and tertiary structures. Secondary structures arise from hydrogen bonding between backbone atoms, such as the carbonyl oxygen and amide hydrogen in polypeptide chains, leading to regular motifs like alpha helices or beta sheets that satisfy the hydrogen-bonding potential of the polar backbone. Tertiary structures form through a combination of these hydrogen bonds along with van der Waals forces, which are weak attractions between non-polar atoms or groups in close proximity, contributing to the overall folding and packing of the macromolecule.[9] Disulfide bridges, covalent bonds formed by the oxidation of sulfhydryl groups on cysteine residues, further reinforce tertiary structures by creating cross-links that lock distant parts of the chain together, enhancing stability in environments where non-covalent interactions might be disrupted. In synthetic macromolecules, particularly vinyl polymers, the stereochemistry of the chain influences properties through tacticity, which describes the spatial arrangement of substituent groups along the backbone. Isotactic polymers feature substituents all on the same side of the chain, promoting crystallinity and rigidity; syndiotactic polymers have alternating substituents, leading to moderate order; while atactic polymers exhibit random placement, resulting in amorphous, flexible materials.[10] This stereochemical variation arises during polymerization and can be controlled using catalysts like Ziegler-Natta systems to tailor mechanical and thermal properties.[11]Classification

By Origin: Synthetic vs. Natural

Macromolecules are broadly classified by their origin into natural and synthetic categories, reflecting differences in how they are produced and their intended applications. Natural macromolecules are generated by living organisms through biosynthetic pathways, resulting in polymers that integrate seamlessly with biological systems. In contrast, synthetic macromolecules are engineered in laboratories or industrial settings, often from non-renewable petrochemical feedstocks, to achieve tailored properties for human use.[12] Natural macromolecules consist primarily of repeating biological monomers such as amino acids, nucleotides, or monosaccharides, forming structures like proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides. For instance, cellulose, a linear polysaccharide composed of β-glucose units linked by glycosidic bonds, is produced by plants and algae to provide structural rigidity in cell walls.[13][12] Silk fibroin, a protein-based macromolecule from silkworms, features repeating amino acid sequences that enable the formation of strong, flexible fibers.[14] These natural polymers have evolved for roles in structural support and material integrity within organisms, and they are valued in applications like biomaterials due to their inherent biocompatibility.[12] Synthetic macromolecules, by comparison, are constructed from simple organic monomers through controlled chemical reactions, yielding polymers with precise architectures and enhanced durability. Polyethylene, derived from ethylene monomers via addition polymerization, forms a simple hydrocarbon chain that imparts flexibility and resistance to moisture, making it ideal for packaging and containers.[15][16] Polystyrene, polymerized from styrene, features a phenyl-substituted backbone that provides rigidity and thermal insulation, commonly used in foam products and disposable items.[12] These materials are designed for mechanical strength, chemical stability, and scalability in industries such as plastics and adhesives.[16][12] Hybrid macromolecules bridge the gap between these categories, incorporating natural-derived components into synthetic frameworks to combine biodegradability with engineered performance. Polylactic acid (PLA), for example, is synthesized from lactic acid monomers fermented from renewable plant sources like corn starch, resulting in an aliphatic polyester that degrades under environmental conditions similar to natural polymers.[17][12] This approach allows synthetics to mimic natural degradation pathways while maintaining customizable properties for applications like medical implants.[17]| Origin | Examples | Primary Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Natural | Cellulose, silk | Biomaterials, structural fibers |

| Synthetic | Polyethylene, polystyrene | Plastics, adhesives, insulation |

| Hybrid | Polylactic acid | Biodegradable packaging, medical devices |

By Architecture: Linear vs. Branched

Macromolecules are classified by their architectural topology, which refers to the arrangement of their molecular chains and significantly influences their overall physical and chemical behavior. Linear macromolecules consist of a single, unbranched chain of repeating units connected end-to-end, featuring only two terminal ends. This straightforward structure allows for efficient packing and alignment of chains, promoting higher degrees of crystallinity and enhanced mechanical properties such as tensile strength.[18][19] In contrast, branched macromolecules incorporate side chains or branches extending from the main chain, disrupting the regularity of the structure and leading to more irregular conformations. These branches reduce interchain packing efficiency compared to linear forms, resulting in lower crystallinity, decreased density, and improved solubility in solvents due to increased free volume and reduced entanglement.[18][19] Examples include low-density polyethylene, where short branches of ethylene units pendant from the main chain alter its rheological behavior relative to its linear counterpart, high-density polyethylene.[19] Advanced branched architectures extend this topology further. Star polymers feature multiple linear arms radiating from a central core or branch point, which can enhance solution properties by minimizing chain entanglement while maintaining compact dimensions.[20][19] Comb polymers, on the other hand, possess a linear backbone with multiple side chains attached along its length, akin to teeth on a comb, leading to unique viscoelastic behaviors suitable for applications requiring tunable flexibility.[20][19] Dendrimers represent a highly ordered branched form, with iterative branching from a core to form globular, tree-like structures that exhibit precise control over size and surface functionality, influencing encapsulation and transport properties.[20] To illustrate these architectures conceptually, a linear macromolecule can be depicted as a continuous chain:Monomer - Monomer - Monomer - ... - End

Monomer - Monomer - Monomer - ... - End

Side Chain

|

Monomer - Monomer - Monomer - ...

|

Side Chain

Side Chain

|

Monomer - Monomer - Monomer - ...

|

Side Chain

Physical and Chemical Properties

Molecular Weight and Size

Macromolecules, particularly polymers, exhibit a range of molecular weights due to their polydisperse nature, necessitating the use of average values to characterize samples. The number-average molecular weight () is defined as the total mass of all chains divided by the total number of chains, given by , where is the number of chains with molecular weight . This average is particularly relevant for properties influenced by the number of molecules, such as colligative effects. In contrast, the weight-average molecular weight () weights each chain by its mass, expressed as , and is more indicative of light-scattering or mechanical properties where larger chains dominate.[21][21] The polydispersity index (PDI), calculated as , quantifies the breadth of the molecular weight distribution; a PDI of 1 indicates monodispersity, while values greater than 1 reflect the typical heterogeneity in synthetic polymers.[21] Beyond weight, macromolecular size is assessed through metrics like the radius of gyration (), which measures the root-mean-square distance of chain segments from the center of mass, defined as , where is the number of segments and is the center of mass. The hydrodynamic radius () describes the effective size in solution, influencing diffusion and viscosity, and is probed by techniques such as dynamic light scattering.[22][22] In the random coil model, pioneered by Paul Flory, chain dimensions scale with length: for an ideal Gaussian chain, , where is the segment length and is the number of segments, yielding ; real chains often follow Flory's self-avoiding walk approximation with due to excluded volume effects.[22] These size parameters directly impact physical behavior, notably solution viscosity, which increases markedly with molecular weight. The Mark-Houwink equation empirically relates intrinsic viscosity to viscosity-average molecular weight as , where and are constants dependent on polymer, solvent, and temperature; typically ranges from 0.5 (theta solvent, random coil) to 0.8 (good solvent, expanded coil), highlighting how larger chains enhance hydrodynamic volume and resistance to flow.[23] A common method for determining these molecular weight averages and distributions is gel permeation chromatography (GPC), also known as size-exclusion chromatography, which separates polymer chains by hydrodynamic volume in solution, allowing calibration against standards to yield , , and PDI.[24]Solubility and Phase Behavior

The solubility of macromolecules in solvents is fundamentally governed by the interactions between polymer chains and solvent molecules, often quantified using the Flory-Huggins theory. This mean-field lattice model describes the free energy of mixing for polymer-solvent systems, where the key parameter is the Flory-Huggins interaction parameter , which measures the compatibility between the components. In its simplified form, relates to the enthalpy of mixing as , where is the enthalpic change, is the gas constant, is temperature, and , are the volume fractions of solvent and polymer, respectively; values of indicate good solubility, while suggests phase separation.[25][26] Phase behavior in macromolecules involves transitions such as the glass transition temperature (), below which the material behaves as a rigid glass, and the melting temperature (), marking the shift from crystalline to amorphous melt states in semicrystalline polymers. These transitions are influenced by factors like chain stiffness, which increases and by restricting segmental mobility and promoting ordered packing; for instance, rigid aromatic groups in the backbone elevate compared to flexible aliphatic chains.[27][28] Higher molecular weights can enhance entanglement, indirectly stabilizing these transitions, though the primary effects stem from structural rigidity.[29] Crystallinity in macromolecules arises from the ability of chains to align into ordered regions, with linear chains exhibiting higher degrees of crystallinity due to their unhindered packing, whereas branched chains disrupt this order, leading to more amorphous structures. In thermoplastics, this results in semicrystalline morphologies where crystalline lamellae coexist with amorphous domains, influencing mechanical properties like toughness and elasticity. The degree of crystallinity typically ranges from 20-80% in such materials, determined by processing conditions and chain architecture.[16][30][31] Representative examples of solubility behaviors include hydrophilic macromolecules, such as polyethylene glycol, which dissolve readily in aqueous environments due to hydrogen bonding with water via polar groups like ether linkages, versus hydrophobic ones like polystyrene, which aggregate and phase-separate in water because of nonpolar aromatic rings that minimize unfavorable interactions with the polar solvent. These behaviors underpin applications from drug delivery in aqueous media to emulsion stability in coatings.[32][33]Synthetic Macromolecules

Polymerization Mechanisms

Polymerization mechanisms for synthetic macromolecules primarily involve two fundamental types: step-growth and chain-growth processes, each characterized by distinct reaction pathways that dictate the molecular weight buildup and structural control of the resulting polymers. Step-growth polymerization proceeds through the sequential reaction of bifunctional monomers, often via condensation reactions that eliminate small molecules like water, leading to gradual chain extension. In contrast, chain-growth polymerization relies on the rapid addition of monomers to active chain ends, enabling faster molecular weight increases but requiring careful initiation and termination control. Step-growth polymerization typically involves condensation reactions between monomers bearing complementary functional groups, such as carboxylic acids and amines in the formation of polyamides like nylon. The extent of reaction, denoted as , directly influences the degree of polymerization via the Carothers equation . Under second-order kinetic assumptions, , where is the rate constant and is time, highlighting the need for high conversions (often >99%) to achieve high molecular weights.[34] This mechanism favors the formation of linear chains from difunctional monomers, though side reactions can introduce branching if multifunctional units are present. Chain-growth polymerization, exemplified by the free radical addition mechanism for styrene to form polystyrene, operates through three key stages: initiation, where a radical species (e.g., from peroxide decomposition) adds to the monomer to create an active chain end; propagation, involving rapid sequential monomer additions to the growing radical; and termination, typically via combination or disproportionation of two radicals, which halts chain growth. This process allows for high monomer conversions at lower extents of reaction compared to step-growth, but often results in broader molecular weight distributions due to varying chain lifetimes. The kinetics follow the Smith-Ewart theory for radical concentrations, emphasizing the role of initiator efficiency in controlling the number of active chains. Advanced methods enhance control over polymerization. Coordination polymerization, pioneered by Ziegler-Natta catalysts (e.g., titanium chloride with aluminum alkyls), facilitates stereoregular addition of olefins like ethylene through a migratory insertion mechanism at coordinatively unsaturated metal sites, enabling the production of high-density polyethylene with tailored tacticity. Living polymerization, first demonstrated by Szwarc in 1956 using anionic initiators for styrene, eliminates termination and chain transfer, yielding polymers with low polydispersity indices (PDI < 1.1-1.5) by allowing all chains to grow uniformly until monomer depletion. These techniques, including controlled radical variants, provide precise molecular weight control via initiator-to-monomer ratios. Factors such as catalysts, temperature, and monomer purity critically influence chain length in both mechanisms. In coordination systems, catalyst composition and support affect active site density and propagation rates, directly impacting degree of polymerization. Temperature modulates reaction kinetics—lowering it reduces side reactions but may slow propagation—while monomer purity prevents poisoning of active centers or premature termination, ensuring longer chains.Common Synthetic Polymers and Applications

Polyethylene, derived from the polymerization of ethylene monomers into long chains of repeating -CH₂-CH₂- units, exists in variants distinguished by their degree of branching, which influences density and crystallinity. High-density polyethylene (HDPE) features a predominantly linear structure with minimal branching, resulting in a density of 0.941–0.965 g/cm³ and a melting temperature (T_m) of approximately 130–136 °C, conferring high strength and rigidity suitable for applications such as rigid packaging bottles and durable pipes for water and gas distribution.[35][36] In contrast, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) incorporates short-chain branching that disrupts crystallinity, yielding a lower density of 0.910–0.940 g/cm³ and a T_m of 105–115 °C, which enables flexibility and is ideal for stretchable films used in food packaging and shrink wraps.[16][37] Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), formed from vinyl chloride monomers, is a rigid thermoplastic often modified with additives like plasticizers (e.g., phthalates) to enhance flexibility for uses in flooring, cables, and medical tubing.[38] These additives, however, raise environmental concerns due to their potential as endocrine disruptors and the overall persistence of PVC as a major component of plastic waste, with its high chlorine content complicating recycling and contributing to long-term pollution in landfills and oceans.[39][40] Similarly, polystyrene (PS), built from styrene monomers, is an amorphous polymer with a glass transition temperature around 100 °C, prized for its clarity and lightweight foam forms but frequently toughened with rubber additives to produce high-impact polystyrene for disposable packaging and insulation.[38] Its environmental footprint includes resistance to biodegradation and challenges in recycling, exacerbating microplastic accumulation in ecosystems.[41][42] Specialty synthetic polymers extend the utility of macromolecules beyond commodity plastics. Synthetic rubbers, such as polyisoprene produced via coordination catalysis to mimic natural rubber's cis-1,4 structure, exhibit high elasticity, tensile strength, and resilience, finding applications in tires, seals, and conveyor belts where abrasion resistance is critical.[43] Conductive polymers like polyaniline, a conjugated polymer with tunable conductivity up to 30 S/cm in its doped form, offer electrical conductivity alongside mechanical flexibility and environmental stability, enabling uses in sensors, anticorrosion coatings, and flexible electronics.[44][45]| Polymer | Monomer | Key Properties | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (HDPE) | Ethylene | Density: 0.941–0.965 g/cm³; T_m: 130–136 °C; high crystallinity, rigidity | Bottles, pipes, containers |

| Polyethylene (LDPE) | Ethylene | Density: 0.910–0.940 g/cm³; T_m: 105–115 °C; branched, flexible | Films, bags, wraps |

| Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) | Vinyl chloride | Rigid base; plasticizer-enhanced flexibility; durable but persistent waste | Pipes, cables, flooring |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Styrene | Amorphous; T_g ~100 °C; lightweight, brittle or rubber-toughened | Packaging, foam insulation, disposables |

| Synthetic polyisoprene | Isoprene | Elastic, high tensile strength; cis-1,4 structure | Tires, seals, belts |

| Polyaniline | Aniline | Conductivity: up to 30 S/cm; stable, tunable doping | Sensors, coatings, electronics |