Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

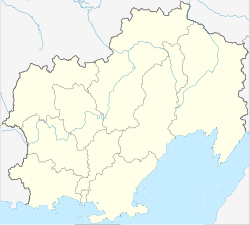

Magadan

View on WikipediaMagadan (Russian: Магадан, IPA: [məɡɐˈdan]) is a port town and the administrative centre of Magadan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the isthmus of the Staritsky Peninsula by the Nagaev Bay; it serves as a gateway to the Kolyma region.

Key Information

Magadan, founded in 1929, was a major transit centre for political prisoners during the Stalin era and the administrative centre of the Dalstroy forced-labor gold mining operation. The town later served as a port for exporting gold and other metals. Magadan plays a significant role in transportation with the Port of Magadan and Sokol Airport.

The local economy relies on gold mining and fisheries, although gold production has declined. The town has various cultural institutions and religious establishments, such as the Orthodox Holy Trinity Cathedral and the Roman Catholic Church of the Nativity. The Mask of Sorrow memorial commemorates Stalin's victims. Magadan experiences a subarctic climate with prolonged and cold winters, causing the soil to remain permanently frozen.

History

[edit]The settlement of Magadan was founded in 1929 in the Ola river valley,[3] near the settlement of Nagayevo. During the Stalin era, Magadan was a major transit centre for inmates sent to Gulag forced labour camps. From 1932 to 1953, it was the administrative centre of the Dalstroy organisation—a vast forced-labour gold-mining operation and forced-labour camp system. The first director of Dalstroy was Eduard Berzin, who between 1932 and 1937 established the infrastructure of the forced labour camps in Magadan. Berzin was executed in 1938 by Stalin, towards the end of the Great Purge.[17]

The town later served as a port for exporting gold and other metals mined in the Kolyma region.[18] Its size and population grew quickly as facilities were rapidly developed for the expanding mining activities in the area. City status was granted to it on July 14, 1939.[19]

Magadan was visited by U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace in May 1944. He took an instant liking to his NKVD host, admired handiwork done by the enslaved political prisoners, and later glowingly called the town a combination of Tennessee Valley Authority and Hudson's Bay Company.[20]

Administrative and municipal status

[edit]Magadan is the administrative centre of the Magadan Oblast.[1] Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is, together with the urban-type settlements of Sokol and Uptar, incorporated as the "town of oblast significance of Magadan"—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, the town of oblast significance of Magadan is incorporated as Magadan Urban Okrug.[12]

Economy and infrastructure

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1939 | 27,313 | — |

| 1959 | 62,225 | +127.8% |

| 1970 | 92,105 | +48.0% |

| 1979 | 121,250 | +31.6% |

| 1989 | 151,652 | +25.1% |

| 2002 | 99,399 | −34.5% |

| 2010 | 95,982 | −3.4% |

| 2021 | 90,757 | −5.4% |

| Source: Census data | ||

Transport

[edit]-

R504 Kolyma Highway near Magadan

-

former Train Station of Magadan-Palatka line

The Port of Magadan is the second largest seaport in the North-East of Russia after Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky located on Nagaev Bay and Sea of Okhotsk.[21] It operates all year round with the help of icebreakers. There is currently no operating railway in Magadan. However, the Magadan-Palatka line was operational between 1941 and 1956. Russian Railways are considering the possibility of building a railway from the Nizhny Bestyakh of the Amur-Yakutsk railway to Magadan by 2035, which will contribute to the development of an area with huge mineral deposits.[22] Magadan is the final destination of the federal highway R504 Kolyma Highway, which connects the region with Yakutia and other parts of Russia. Anadyr Highway, currently under construction, will provide access to Chukotka Autonomous Okrug.[23] Sokol Airport and Magadan-13 airport provide access to air transport for numerous destinations in Russia with the former being for big aircraft and the latter is mainly for small aircraft.

Magadan is also the home of the Magadan/Sokol Flight Information Region (FIR) and Magadan Oceanic FIR, which controls the Northeastern part of the Russia and its Arctic airspace.[24][25] Most of the westbound transpacific flights from North America to Asia will use those FIRs.[26]

Economy

[edit]The principal sources of income for the local economy are gold mining and fisheries. By 2007, gold production had declined.[27] Fishing production declined and was well below the allocated quotas, apparently as a result of an aging fishing fleet.[28] Other local industries include pasta and sausage plants, and a distillery.[29] Although farming is difficult owing to the harsh climate, there are many public and private farming enterprises.[citation needed]

Other

[edit]The Central Intelligence Agency wrote a report on Ship Repair Yard No. 2 near Magadan in June 1965.[30] Magadan was repeatedly reported as a base for the Soviet Navy during the Cold War.[31]

Culture and religion

[edit]Culture

[edit]-

Gornyak Cinema

-

Magadan Theatre

-

Magadan Hotel

-

Polytechnic Magadan

It has a number of cultural institutions, including the Regional Museum of Anthropology, a geological museum, a regional library and a university. Magadanskaya Pravda is the main newspaper.[citation needed]

The town figures prominently in the gulag literature of Varlam Shalamov and in the eponymous song by Mikhail Krug.[citation needed] Actor of film and stage Georgiy Zhzhonov worked at Magadan Theatre for two years after being released from a gulag in May 1945.[32]

Magadan was home to Eastern Syndrome a Soviet and Russian rock group founded there in 1986.[citation needed]

The town was a focal point of the Long Way Round TV series of a motorcycle journey made by Ewan McGregor, Charley Boorman and their team in 2004.[citation needed][33]

Religion

[edit]-

Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh

-

Cathedral of the Holy Spirit

The town features the recent Orthodox Cathedral of the Life-Giving Trinity (completed in 2008), and the Roman Catholic Church of the Nativity (completed in 2002[34]), among others.

Memorials

[edit]-

Magadan Coat of Arms

-

Lenin monument (2011)

-

Lenin monument (2008)

The Mask of Sorrow memorial, a large sculpture in memory of Stalin's victims, was designed by Ernst Neizvestny. The Church of the Nativity ministers to survivors of the labor camps. It is staffed by several priests and nuns.

Sport

[edit]-

Hiking in Marchekanskaya

-

Magadan Palace of Sports

Geography

[edit]The Magadanka River, a 192 km long river flowing to the Sea of Okhotsk, passes the city. The city is located on the isthmus of the Staritsky Peninsula by the Nagaev Bay.

-

View of Gertner Bay, Cape Red and Kekurny Island

-

Nagaev Bay

-

Gorokhovoe Pole

-

Magadan beach, July 2011

Ecologically situated in the Northeast Siberian taiga, the town's arboreal flora is made up of conifer trees, such as firs and larches, and silver birches.[35] The city is surrounded by mountains to the west and northeast. Permafrost and tundra cover most of the region. The growing season is only one hundred days long.[36]

The city of Magadan is on the same longitude as the suburbs of Greater Western Sydney, Australia, which lie on the eastern end of the 150th meridian east line, bordering the 151st meridian and is on the same latitude as Southern Scandinavia, and the far north of Scotland.

Climate

[edit]The climate of Magadan is subarctic (Köppen climate classification Dfc). Winters are prolonged and very cold, with up to six months of sub-zero high temperatures, so that the soil remains permanently frozen; although they are still much milder than those of interior eastern Siberia. Average temperatures on the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk range from −22 °C (−8 °F) in January to +12 °C (54 °F) in July. Average temperatures in the interior range from −38 °C (−36 °F) in January to +16 °C (61 °F) in July. Due to the wet nature of October and November, a snowpack is built up early, which then lasts throughout the winter even while the influence from the Siberian High lowers precipitation throughout those months.

- Highest temperature: 27.8 °C (82.0 °F) on July 15, 2021

- Lowest temperature: −37 °C (−35 °F) on December 20, 1995

- Warmest month: 14.1 °C (57.4 °F) in July, 2009

- Coldest month: −25.0 °C (−13.0 °F) in January, 1933

- Warmest year: −1.3 °C (29.7 °F) in 2017

- Coldest year: −5.0 °C (23.0 °F) in 1967

- Highest daily Precipitation: 108 millimetres (4.3 in) in July, 2014

- Wettest month: 306 millimetres (12.0 in) in July, 2014

- Wettest year: 1,004 millimetres (39.5 in) in 1950

- Driest year: 226 millimetres (8.9 in) in 1947

| Climate data for Magadan (1991–2020, extremes 1930–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −13.3 (8.1) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

0.5 (32.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−15.4 (4.3) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −17.8 (0.0) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −34.6 (−30.3) |

−33.3 (−27.9) |

−30.8 (−23.4) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−26.9 (−16.4) |

−37 (−35) |

−37 (−35) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18 (0.7) |

14 (0.6) |

21 (0.8) |

24 (0.9) |

40 (1.6) |

52 (2.0) |

67 (2.6) |

102 (4.0) |

85 (3.3) |

75 (3.0) |

61 (2.4) |

27 (1.1) |

586 (23.1) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 26 (10) |

24 (9.4) |

25 (9.8) |

24 (9.4) |

9 (3.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

5 (2.0) |

23 (9.1) |

31 (12) |

31 (12) |

| Average rainy days | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 2 | 11 | 17 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 10 | 2 | 0.1 | 103 |

| Average snowy days | 16 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 19 | 16 | 127 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65 | 64 | 65 | 71 | 78 | 82 | 86 | 83 | 78 | 69 | 66 | 64 | 73 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 77.3 | 132.6 | 211.4 | 235.9 | 226.3 | 228.5 | 196.0 | 175.6 | 157.3 | 142.9 | 79.9 | 50.2 | 1,913.9 |

| Source 1: Погода и Климат[37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[38] | |||||||||||||

Education

[edit]- North-Eastern State University (СВГУ, formerly Northern International University)

- The University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) offers a scholarship to full-time students from Magadan.

Notable people

[edit]- Anton Belyaev (b. 1979), musician, lead singer of Therr Maitz

- Anya Garnis (b. 1982), professional dancer, raised in Magadan, but not born there.

- Nikolai Getman (1917–2004), artist

- Dimitry Ipatov (b. 1984), ski jumper

- Inna Korobkina (b. 1981), actress

- Vadim Kozin (1903–1994), tenor

- Nina Lugovskaya (1918–1993), artist

- Sasha Luss (b. 1992), fashion model

- Gena Marvin (b. 2000s), performance artist

- Viktor Rybakov (b. 1956), former European amateur boxing champion

- Pavel Vinogradov (b. 1953), cosmonaut

- Yelena Vyalbe (b. 1968), Olympic cross-country skier

Twin towns and sister cities

[edit]Magadan is twinned with:

Anchorage, United States (1991)

Anchorage, United States (1991) Tonghua, Jilin, China (1992)

Tonghua, Jilin, China (1992) Zlatitsa, Bulgaria (2012)

Zlatitsa, Bulgaria (2012) Shuangyashan, China (2013)

Shuangyashan, China (2013)- In 2022 Jelgava, Latvia (2006) suspended the cooperation agreements with Magadan due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[39]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Law #1292-OZ

- ^ Article 4 of the Charter of Magadan does not specify any town symbols other than a flag and a coat of arms

- ^ a b c Vazhenin, p. 4

- ^ Charter of Magadan, Article 24

- ^ Official website of Magadan Town Duma. Andrey Anatolyevich Popov Archived June 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ Official website of Magadan's Mayor Office. Larisa Olegovna Polikanova Archived March 17, 2025(Timestamp length), at the Wayback Machine, Mayor of Magadan (in Russian)

- ^ Charter of Magadan, Articles 33 and 35.1

- ^ Official website of Magadan's Mayor Office. Official Site of Magadan. Обновление материалов генерального плана 1994 г. Пояснительная записка. Archived May 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Charter of Magadan Oblast, Article 38

- ^ a b c Law #489-OZ

- ^ "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- ^ Decision #49-D

- ^ Оценка численности населения на 2024 г.

- ^ Kapuscinski, Imperium, 2019, pp. 200-204

- ^ Козлов, А. Г. (1989). Магадан. Конспект прошлого. Магаданское книжное издательство. p. 16. ISBN 5-7581-0066-8.

- ^ "Magadan". Russian Life. July 1, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ John C. Culver, John Hyde, American Dreamer: The Life and Times of Henry A. Wallace, 1 Sep 2001

- ^ "Главная страница | Ассоциация морских торговых портов". www.morport.com. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "РЖД изучают возможность строительства железной дороги до Магадана". news.mail.ru. August 27, 2020. Archived from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Дорогу Колыма – Омсукчан – Омолон – Анадырь начали строить в Магаданской области - MagadanMedia". magadanmedia.ru. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "AIR TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT OPERATIONAL CONTINGENCY PLAN FOR THE ARCTIC AREA" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. December 9, 2011.

- ^ "North-East Air Navigation, Magadan". GKOVD.

- ^ "User Preferred Routes within Magadan ACC Airspace" (PDF). GKOVD. FAA. 2020.

- ^ Russian gold mine production declined four tonnes in 2006 Archived June 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Mineweb, 31 January 2007

- ^ New Russian Fishing Quotas Distribution System, Strategis international market reports[dead link], 28 August 2004

- ^ Magadan Region from Kommersant, Russia's Daily Online Archived October 25, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ "Magadan Ship Repair Yard No. 2". June 1965.

- ^ See Military Balance 1990-91, p.42.

- ^ "Georgiy Zhzhonov's Russian Cross". ФОНД РУССКИЙ МИР. March 21, 2015. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ McGregor, Ewan (June 2009). Long Way Down : An Epic Journey by Motorcycle from Scotland to South Africa (1st ed.). New York: Atria Books. ISBN 9781416577485.

- ^ "Magadan, Russian Federation: Catholic Parish of the Nativity of Jesus". The Catholic Travel Guide. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Sakha Republic & Magadan Region is pine trees and rushing rivers by the Lonely Planet

- ^ THE SEA OF OKHOTSK by the National Geographic

- ^ "КЛИМАТ МАГАДАНА" (in Russian). Погода и Климат. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ "Magadan Climate Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ Jelgava suspends cooperation agreement with twin cities Magadan (Russia) and Baranovichi (Belarus)

Sources

[edit]- Магаданская городская Дума. Решение №96-Д от 26 августа 2005 г. «Устав муниципального образования "Город Магадан"», в ред. Решения №61-Д от 15 сентября 2017 г. «О внесении изменений в Устав муниципального образования "Город Магадан"». Вступил в силу 1 января 2006 г. (за исключением отдельных положений). Опубликован: "Вечерний Магадан", №3(861), 19 января 2006 г. (Magadan Town Duma. Decision #96-D of August 26, 2005 Charter of the Municipal Formation of the "Town of Magadan", as amended by the Decision #61-D of September 15, 2017 On Amending the Charter of the Municipal Formation of the "Town of Magadan". Effective as of January 1, 2006 (with the exception of certain clauses).).

- Магаданская городская Дума. Решение №49-Д от 1 июля 1999 г. «О установлении общегородского праздника "День города Магадана"». (Magadan Town Duma. Decision #49-D of July 1, 1999 On Establishing Town Holiday "Day of the Town of Magadan". ).

- Магаданская областная Дума. Закон №1292-ОЗ от 9 июня 2010 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Магаданской области», в ред. Закона №1756-ОЗ от 9 июня 2014 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Магаданской области "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Магаданской области"». Вступил в силу через 10 дней после дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: Приложение к газете "Магаданская правда", №63(20183), 16 июня 2010 г. (Magadan Oblast Duma. Law #1292-OZ of June 9, 2010 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Magadan Oblast, as amended by the Law #1756-OZ of June 9, 2014 On Amending the Law of Magadan Oblast "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Magadan Oblast". Effective as of the day which is 10 days after the official publication date.).

- Магаданская областная Дума. №218-ОЗ 28 декабря 2001 г. «Устав Магаданской области», в ред. Закона №2185-ОЗ от 14 июня 2017 г. «О принятии поправки к Уставу Магаданской области». Вступил в силу по истечении десяти дней со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Магаданская правда", №201 (18919), 29 декабря 2001 г. (Magadan Oblast Duma. Law #218-OZ of December 28, 2001 Charter of Magadan Oblast, as amended by the Law #2185-OZ of June 14, 2017 On Adopting an Amendment to the Charter of Magadan Oblast. Effective as of the day ten days after the official publication date.).

- Магаданская областная Дума. Закон №489-ОЗ от 6 декабря 2004 г. «О муниципальном образовании "город Магадан"», в ред. Закона №1578-ОЗ от 6 марта 2013 г. «О внесении изменения в статью 3 Закона Магаданской области "О муниципальном образовании "город Магадан"». Вступил в силу 31 декабря 2004 г.. Опубликован: "Магаданская правда", №140 (19364), 15 декабря 2004 г. (Magadan Oblast Duma. Law #489-OZ of December 6, 2004 On the Municipal Formation of the "Town of Magadan", as amended by the Law #1578-OZ of March 6, 2013 On Amending Article 3 of the Law of Magadan Oblast "On the Municipal Formation of the "Town of Magadan". Effective as of December 31, 2004.).

- Ryszard Kapuscinski, Imperium, Granta, 2019, ISBN 9781783785254

- McGregor, E & Boorman, C: Long Way Round. Time Warner Books, 2004. ISBN 0-7515-3680-6

- Nordlander, David J. “Origins of a Gulag Capital: Magadan and Stalinist Control in the Early 1930s.” Slavic Review, vol. 57, no. 4, 1998, pp. 791–812. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2501047. Accessed 14 Aug. 2025.

External links

[edit] Magadan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Magadan travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Magadan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Magadan at Wikimedia Commons- Б. П. Важенин (B. P. Vazhenin). "Магадан: к историческим истокам названия" (Magadan: The Historical Sources of Its Name). Российская академия наук, Дальневосточное отделение. Магадан, 2003.

- Map of Magadan (in Russian)

- Documentary *** GOLD*** - lost in Siberia GOLD - lost in Siberia / GOUD - vergeten in Siberië / ЗОЛОТО/БОЛЬ - потеряно в Сибири (1994) by Gerard Jacobs and Theo Uittenbogaard (VPRO/The Netherlands/1994) was filmed in the summer of 1993 in Magadan, along the Road of Bones, through Ust-Umshug and Susuman and at the Sverovostok Zoloto gold mine, Siberia, by the first foreign film crew ever, visiting the Kolyma District -which had been under control of the Soviet secret service-, under the company name Dalstroj, for over 60 years.

- The road up to the Kolyma river. Documentary: repressed in Magadan recall. To watch the video.

Magadan

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Physical Features

Magadan is a port city situated on the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk in northeastern Russia, specifically along the shores of Nagaev Bay within Taui Bay, at approximately 59°34′N 150°48′E.[11][12][13] It lies in the Far Eastern Federal District and functions as the administrative center of Magadan Oblast, serving as the main gateway to the inland Kolyma region via road and river transport connections.[11][1] The city's terrain features low coastal hills rising to elevations around 70 meters above sea level, with significant topographic variations extending to over 400 meters in nearby areas, contributing to a rugged, dissected landscape.[14][15] Surrounding the urban area are the Kolyma Highlands to the east and influences from the Anadyr Plateau to the north, where mountain ranges predominate with peaks generally below 1,500 meters, though some reach 2,586 meters.[11][5] The broader oblast landscape consists of taiga woodlands, tundra, and permafrost-covered lowlands, with sparse larch forests and limited vegetation adapted to subarctic conditions.[5]Climate and Environmental Conditions

Magadan lies within a subarctic climate zone (Köppen Dfc), featuring prolonged cold winters and brief mild summers influenced by its coastal position on the Sea of Okhotsk.[15] Annual temperatures average -3.3°C, with winter daytime highs around -15°C in February and nighttime lows reaching -21°C, while August brings average highs of 15°C and lows of 11°C.[16] [17] Precipitation totals approximately 533 mm yearly, concentrated as snowfall during the extended cold season from late November to early April and rainfall in summer, with August recording the highest monthly average at 72 mm.[18] [17] Extreme weather events underscore the region's severity: temperatures rarely drop below -33°C or exceed 21°C, though records include a high of 27°C on July 8, 2015.[15] [19] Persistent winds, blizzards, and fog from the nearby sea contribute to harsh conditions, limiting vegetation to tundra and taiga species adapted to permafrost soils.[15] Environmental pressures stem largely from gold mining operations across Magadan Oblast, which disrupt permafrost in the cryolithozone, leading to landscape degradation, waste rock accumulation, and elevated sediment loads in rivers that impair aquatic ecosystems.[20] [21] Tailings dam failures, such as the 2018 Karamken incident, have released toxic elements into waterways, contaminating fish stocks and drinking sources while posing risks to hydraulic structures in unstable permafrost terrain.[22] Air quality suffers from emissions tied to diesel and low-grade coal combustion for heating and power, compounded by reliance on firewood amid fuel shortages, though crisis periods have occasionally reduced industrial discharges.[5] [23] These activities threaten biodiversity in fragile Arctic-like environments, with ongoing expansion of placer mining exacerbating erosion and pollution without robust mitigation evident in regional assessments.[21]History

Indigenous and Pre-Soviet Period

The territory of present-day Magadan Oblast was inhabited by indigenous groups for millennia prior to Russian contact, primarily Paleo-Siberian Yukaghirs and Tungusic-speaking Evens, who subsisted through nomadic reindeer herding, elk hunting, and riverine fishing in the Kolyma River basin and surrounding taiga-tundra ecotone. Yukaghirs, divided into taiga-adapted Upper Kolyma subgroups and tundra-oriented northern variants, numbered in the low thousands and maintained oral traditions reflecting deep environmental knowledge, with populations concentrated along the Kolyma and Alazeya rivers.[24][25] Evens, who arrived via migrations from Baikal-region Tungusic heartlands around the 12th-13th centuries, similarly relied on mobile pastoralism and supplemented diets with marine resources near coastal zones, forming small clan-based bands rather than fixed villages.[26][27] These groups exhibited genetic continuity with ancient northeastern Siberian lineages, evidenced by Y-chromosome haplogroups like N1a1 tracing back over 2,000 years in Even samples from the region.[28] Russian expansion into the Kolyma region commenced in the mid-17th century, driven by fur trade ambitions, with Cossack explorer Mikhail Stadukhin reaching the Kolyma River mouth in 1644 via overland routes from the Lena, establishing initial winter quarters and initiating yasak (fur tribute) extraction from Yukaghir and Even communities.[29] Semyon Dezhnev's 1648 coastal voyage from the Kolyma eastward along the Arctic shore to the Anadyr further mapped the area's contours, though these expeditions prioritized reconnaissance over colonization, resulting in transient outposts rather than enduring settlements.[29] By the late 17th century, modest forts like Srednekolymsk (founded circa 1644-1650) functioned as administrative nodes for tribute collection in the upper Kolyma valley, but the coastal Nagaeva Bay vicinity—site of modern Magadan—saw negligible permanent Russian presence, limited to occasional trader forays amid ongoing indigenous autonomy.[30] Under imperial Russian administration, integrated into Yakutsk Okrug by the 18th century, the region endured sporadic Cossack enforcement of tribute quotas, which strained indigenous demographics through disease introduction (e.g., smallpox epidemics decimating Yukaghir bands) and resource depletion, though direct governance remained lax due to logistical remoteness.[26] Minor Even-Yukaghir intermarriages and adoptions of Russian trade goods occurred, but cultural assimilation was minimal; populations hovered below 5,000 combined for these groups in the broader Kolyma lowlands. Isolated gold panning emerged in the 1890s-1910s, drawing a handful of prospectors to upper tributaries, yet yielded only artisanal outputs without infrastructure, preserving the area's pre-industrial character until revolutionary upheavals.[31]Establishment Under Soviet Rule

In late 1931, the Soviet government established Dalstroy (Far North Construction Trust), a state enterprise under the NKVD tasked with exploiting mineral resources, particularly gold, in the Kolyma River basin of northeastern Siberia.[32] [33] This followed a Central Committee resolution on November 11, 1931, titled "On Kolyma," which aimed to develop the region's untapped deposits to support industrialization and foreign currency needs.[33] Magadan, initially a rudimentary settlement at Nagaeva Bay on the Sea of Okhotsk, was selected as Dalstroy's administrative headquarters due to its ice-free port potential for shipping supplies and extracted resources.[32] The site's prior use as a trading post for indigenous Even and Yukaghir peoples was overshadowed by its strategic value for Soviet extraction efforts. Eduard Berzin, appointed Dalstroy's first director in 1931, oversaw the rapid buildup of infrastructure, including docks, warehouses, and housing, much of it constructed by initial contingents of forced laborers arriving by ship in June 1932 aboard vessels like the Kahovskaya and Dneprostroi.[32] By 1932, Dalstroy processed nearly 10,000 prisoners at Magadan, enabling gold output to rise from 511 kg that year to over 33,000 kg by 1936, funding key Soviet projects.[32] Administrative growth included establishing technical colleges and engineering facilities by the mid-1930s to support mining operations, though Berzin's tenure ended in 1937 amid Stalin's purges, with subsequent leaders like K.A. Gerasimov and I.F. Nikishov refocusing on production quotas.[32] Magadan received official city status on July 14, 1939, formalizing its role as the regional hub, though this date has been critiqued as obscuring earlier, more pivotal developments tied to Dalstroy's founding.[33] Prior to this, the settlement expanded from a few hundred inhabitants to a functional administrative center serving thousands, reliant on maritime logistics for survival in the harsh subarctic environment.[32] This establishment phase laid the groundwork for Magadan's integration into the Soviet command economy, prioritizing resource extraction over civilian welfare.[33]Gulag System and Kolyma Labor Camps

The Kolyma labor camps, part of the Soviet Gulag system, were established in the early 1930s to exploit the region's gold deposits through forced labor, with Magadan serving as the administrative headquarters of Dalstroy, the Far Northern Construction Trust created in autumn 1931.[32] Dalstroy, placed under NKVD control in 1934, oversaw operations across a vast territory encompassing the Kolyma River basin and surrounding areas, utilizing the Sevvostlag (North-Eastern Corrective Labor Camps) network, which began forming in April 1932.[34] [32] Prisoners, transported primarily by sea to Magadan's port, were then distributed to over 130 camps for gold mining, road construction, and infrastructure development, with the first major convoy of 9,928 arriving in June 1932 via ships such as the Kahovskaya and Dneprostroi.[32] [34] Prisoner numbers in Dalstroy facilities grew rapidly: 32,304 in 1934, 44,601 in 1935, 62,703 in 1936, and 163,475 by 1939, comprising about 85% of the workforce in peak years.[32] By 1944, the total stood at 73,672 inmates amid a broader labor force of 167,686 including free workers, many former prisoners; overall, from 1932 to 1956, 876,043 individuals passed through the system.[34] Labor conditions were brutal, involving 11-hour workdays in subarctic temperatures often dropping below -50°C (-58°F), leading to widespread hypothermia, frostbite, malnutrition, and scurvy; mortality spiked during the Great Purges of 1937–1938 and wartime shortages, with 16,276 deaths recorded in 1942 alone and a cumulative total of 127,792 fatalities over the system's lifespan.[34] [32] The Kolyma Highway, known as the "Road of Bones" due to the prisoner deaths during its construction starting in 1932, connected Magadan to inland camps, facilitating resource extraction but at immense human cost.[31] Economically, the camps prioritized gold production to fund Soviet industrialization, yielding 511 kg in 1932, rising to 33,360 kg by 1936 and 66,314 kg in 1939, with exports providing critical foreign currency.[32] Dalstroy's operations, while masked as correctional labor, functioned primarily as a mechanism for state resource acquisition, with productivity hampered by inadequate equipment, emaciated workers, and administrative purges of camp leadership.[32] The system persisted until the mid-1950s, with Sevvostlag formally dissolved in 1954 following Stalin's death in 1953 and subsequent amnesties, after which surviving infrastructure and personnel transitioned to civilian use in Magadan Oblast.[34] Today, the Mask of Sorrow monument in Magadan commemorates the victims, underscoring the scale of repression in the region.Post-Stalin Era and Late Soviet Development

Following Joseph Stalin's death on March 5, 1953, the Kolyma forced labor camps under Dalstroy faced rapid reforms amid the Soviet Union's broader dismantling of the Gulag system, with prisoner releases accelerating through amnesties and administrative changes. [35] Between 1953 and 1954, roughly 102,000 individuals—primarily former inmates—departed the region, causing a sharp initial population decline as the forced labor model collapsed. [30] Replacement by voluntary workers proved limited, with only 13,677 free hires (vol'nonaemnye) arriving in 1955, drawn by elevated "northern coefficients" wage premiums designed to populate remote areas. [30] Dalstroy itself was restructured, separating camp oversight from economic operations; by mid-1957, its mining functions integrated into the Ministry of Metallurgy as part of nationwide industrial decentralization, ending the entity's direct role in penal labor. [36] On December 3, 1953, Magadan Oblast was created from northern Khabarovsk Krai territories, institutionalizing Magadan as the administrative hub for the Kolyma economic zone and reflecting the shift toward civilian governance in the post-Gulag era. [11] Gold extraction, which had relied on inmate labor producing up to 30 tons annually in peak Stalin years, transitioned to state-managed free labor under the new ministry structure, sustaining output through mechanized dredging and open-pit methods despite logistical challenges in the subarctic terrain. [31] Fisheries and tin mining supplemented the economy, with Magadan's port serving as the primary import-export node for heavy equipment and exports, though perennial shortages of skilled personnel hampered efficiency. [37] In the late Soviet decades, demographic recovery accelerated via targeted migration policies, propelling Magadan Oblast's population to a historical high of 391,687 by 1989, fueled by subsidies, housing guarantees, and bonuses for Far North residency. [1] Infrastructure advanced modestly, including expansions at Sokol Airport for passenger and cargo flights and upgrades to the R-504 Kolyma Highway—originally a Gulag-built "Road of Bones"—to facilitate year-round trucking of ore and supplies over 2,000 kilometers of permafrost. [37] Economic dependence on central planning persisted, with gold output stabilizing at around 20-25 tons yearly by the 1980s, but underlying vulnerabilities emerged from overreliance on extractives and isolation, foreshadowing post-1991 contractions. [31]Post-Soviet Transition and Modern Challenges

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Magadan Oblast experienced a profound economic contraction, with regional output plummeting due to the abrupt end of central planning, subsidies, and inter-republican supply chains that had sustained its remote industrial base. Gold mining, which accounted for a significant portion of the oblast's production, saw initial declines as state enterprises faced privatization delays and market disruptions, though by the early 2000s, private firms restored output to represent about 25% of Russia's total gold production. Fisheries, the second pillar of the economy, suffered from reduced state support and fluctuating quotas, exacerbating food security issues in a region lacking diversified agriculture. These shifts triggered widespread unemployment and hyperinflation, prompting mass out-migration as residents sought opportunities in more accessible western Russia.[5] The oblast's population, which stood at 384,525 in 1991, underwent one of Russia's steepest declines, dropping to approximately 156,000 by 2010, with the most acute losses between 1991 and 1996 driven by natural decrease and net out-migration exceeding 200,000 people. Rural areas depopulated fastest, falling from 64,000 residents outside urban centers in the early 1990s to under 20,000 by 2010, as peripheral settlements collapsed without Soviet-era transport and provisioning. Urban Magadan retained a core but lost over 40% of its inhabitants, straining social services and amplifying labor shortages in extractive industries. This demographic hemorrhage reflected causal factors like the unviability of sustaining a high-cost northern workforce without command-economy distortions, compounded by inadequate post-reform infrastructure investments.[38][1] Contemporary challenges persist amid heavy reliance on volatile commodity prices, with mining (gold, silver, tin) generating over 80% of budget revenues but vulnerable to global fluctuations and extraction limits in aging deposits. Permafrost thaw, accelerated by rising Arctic temperatures—averaging 2-3°C warmer since 1990—has destabilized roads, pipelines, and buildings, imposing annual repair costs estimated in billions of rubles regionally and threatening up to 10% of GDP in affected northern economies through disrupted logistics. The R504 Kolyma Highway, the primary land link to the interior, faces seasonal unreliability from milder winters shortening ice-road viability by 20-30 days per year, inflating transport expenses that already exceed 20% of production costs for remote mines. Fisheries output, while stable at around 100,000-150,000 tons annually, contends with overexploitation and international quotas limiting Sea of Okhotsk stocks. Energy shortages, rooted in aging coal-fired plants and diesel dependence, periodically halt operations, underscoring the oblast's isolation—over 6,000 km from Moscow—with air and sea freight dominating at prohibitive rates. Federal initiatives, such as Far East development subsidies since 2014, have mitigated some decline but fail to offset structural depopulation, projected to reduce the workforce by another 15-20% by 2030 absent diversification.[39][40][41]Administrative and Demographic Profile

Governance and Administrative Status

Magadan functions as the administrative center of Magadan Oblast, a federal subject of the Russian Federation within the Far Eastern Federal District. The oblast encompasses 462,464 square kilometers and was formally established on December 3, 1953, as part of the Soviet administrative reorganization in the Far East.[11][42] The governance structure of Magadan Oblast features a unicameral legislative body, the Magadan Regional Duma, which serves as the permanent representative authority with 21 deputies elected for five-year terms—11 by proportional party lists and 10 by single-mandate constituencies. The current Duma was elected in September 2020, with its term set to expire in September 2025. Executive authority resides with the Governor, who oversees regional policy implementation and reports to federal authorities; Sergey Nosov has held this position since September 13, 2018, as confirmed in official interactions as recent as August 2025.[11][6] At the municipal level, the city of Magadan operates under a charter that delineates local self-government, with executive powers vested in the Mayor and legislative functions in the City Duma. Larisa Polikanova serves as Mayor, a role highlighted in federal-level discussions on urban development in August 2025. This dual structure aligns with Russia's federal framework, where oblast-level decisions influence city administration, particularly in resource allocation for infrastructure and services in this remote northern territory.[43]Population Dynamics and Demographics

The population of Magadan city stood at 90,757 according to the 2021 Russian census, representing a decline from 95,982 in 2010.[44] By 2024 estimates, it had further decreased to approximately 89,193, reflecting an annual change of about -0.77%.[45] This downward trend mirrors broader depopulation in the Russian Far East, with the city's numbers peaking at around 106,400 in 2002 before contracting due to sustained net out-migration.[46] Historically, Magadan's population expanded rapidly from the 1930s through the late Soviet period, driven by forced labor inflows under the Gulag system and subsequent industrial development in mining and fisheries, which attracted workers with incentives like higher wages and housing subsidies for northern regions. Post-1991, the dissolution of the USSR triggered economic contraction, including reduced state support and job losses in resource extraction, prompting mass emigration to warmer, more prosperous areas in European Russia. Harsh subarctic conditions, including extreme cold and isolation, exacerbated outflows, with migration accounting for the bulk of the decline rather than natural decrease alone, though the latter has intensified recently.[47] [5] Demographically, Magadan remains overwhelmingly ethnic Russian, comprising 87.71% of the population per 2020 census data, with Ukrainians at 2.70% and smaller shares of indigenous groups like Evens (around 1-2%).[11] Urbanization is near-total, as the city dominates the oblast's 133,387 residents (2024 estimate), with sparse rural settlements housing indigenous peoples engaged in reindeer herding and fishing. Vital statistics underscore challenges: in the oblast, the 2024 birth rate was 7.6 per 1,000, far below the death rate of 12.7 per 1,000, yielding a negative natural increase of over 600 persons and compounding migration-driven losses. High mortality stems from factors like cardiovascular diseases, accidents, and alcohol-related issues prevalent in remote northern settings, while low fertility reflects delayed family formation amid economic uncertainty.[48]Economy and Infrastructure

Primary Industries: Mining and Fisheries

The economy of Magadan Oblast relies heavily on mining, with gold extraction serving as the dominant activity. In 2024, the region produced 54.1 tons of gold, marking a 13% increase from the 47.968 tons recorded in 2023.[49][50] This output positions Magadan as a leading gold-producing area in Russia, contributing significantly to national totals through operations at major sites such as the Natalka mine, operated by Polyus, which yielded approximately 15.5 tons in 2023, and the Pavlik deposit, where production reached 12.8 tons in 2024, up 38% from the previous year.[51][52] Silver mining complements gold efforts, notably at the Dukat mine, owned by Polymetal International, which produced an estimated 7.7 million ounces in recent operations.[53] Other minerals including tin and coal are extracted, though on a smaller scale relative to precious metals.[54] Fisheries constitute another key primary sector, centered on commercial and coastal operations in the Sea of Okhotsk. The industry focuses on salmon species, with catches showing variability; in the 2025 season, Magadan recorded 8.6 thousand tons of salmon by mid-year, a 117% rise over the same period in 2023.[55] Annual sea fish production, excluding aquaculture, fluctuates between 78,000 and 102,000 tons, as evidenced by 78,989 tons in 2021 and a peak of 102,381 tons in 2018.[56] The Port of Magadan facilitates exports, supporting an industry bolstered by investments exceeding 30 billion rubles in vessel construction and infrastructure development as of 2022.[57] Despite these efforts, fisheries output remains modest compared to mining, constrained by environmental factors and regional quotas.[11]Transportation and Logistics Networks

Magadan's transportation infrastructure centers on maritime, aviation, and rudimentary road networks, essential for supplying this remote Arctic-adjacent city amid permafrost and extreme weather constraints. The port serves as the principal gateway for bulk cargo imports, while the airport handles passenger and limited freight traffic, and roads provide tenuous overland connectivity to interior regions. Absence of rail links underscores logistical vulnerabilities, with reliance on seasonal shipping and airlift for perishables and urgent goods.[58] The R504 Kolyma Highway, spanning approximately 2,032 kilometers from Magadan to Nizhny Bestyakh near Yakutsk, forms the core road artery, facilitating freight to mining sites and regional travel despite frequent closures from flooding, erosion, and ice. Constructed largely with forced labor in the 1930s-1950s, the unpaved and gravel sections demand specialized vehicles, with annual maintenance challenged by subzero temperatures and thawing soils. Local urban roads, including alignments in the metropolitan area, undergo upgrades to support heavier loads from gold extraction operations.[59][60] Commercial shipping via the Port of Magadan, located in Nagaeva Bay, accommodates dry bulk, containers, oil products, and general cargo across 13 berths, with regular lines from Vladivostok delivering transit times of 4-6 days for containerized goods. The facility handles diverse freight including mining equipment and consumer staples, though winter ice necessitates icebreaker assistance and limits navigation from November to May. Operators like FESCO integrate the port into broader Far East logistics, emphasizing refrigerated and hazardous material handling.[58] Sokol Airport (GDX), situated 25 kilometers north of the city, operates as the sole major airfield with a 3,000-meter runway capable of accommodating medium-haul jets up to Boeing 767 size, supporting 11 domestic destinations primarily via Moscow and regional hubs. A new passenger terminal, opened on December 23, 2024, boosts hourly capacity to 800 passengers, enhancing connectivity for workforce mobility in extractive industries; pre-upgrade volumes reached 425,652 passengers in 2019. Air cargo supplements sea routes for high-value or time-sensitive shipments.[61][62] Rail infrastructure remains negligible, with historical narrow-gauge lines to Gulag-era camps dismantled post-1950s; no standard-gauge connection exists to the national network. Proposed extensions from Yakutia's Nizhny Bestyakh, estimated at 1.6 trillion rubles (about $26 billion) as of 2022, aim to integrate Magadan but face delays due to terrain, costs, and funding, leaving logistics dependent on multimodal trucking from distant junctions.[63] Logistics networks prioritize resilience against isolation, with port and highway synergies enabling just-in-time delivery for fisheries and mining outputs like gold and tin, though high costs—exacerbated by fuel dependencies and weather disruptions—constrain economic scalability. Federal investments target infrastructure hardening, yet systemic bottlenecks persist in coordinating sea-road-air handoffs.[60]Economic Challenges and Recent Developments

Magadan's economy grapples with structural vulnerabilities rooted in its extreme remoteness, subarctic conditions, and limited infrastructure, which inflate logistics expenses and constrain supply chains reliant on the port and Kolyma Highway. Dependence on volatile extractive sectors—gold mining comprising 88% of industrial production—exposes the region to commodity price swings and operational risks from harsh weather disrupting activities.[10] Population stagnation around 134,000 in 2024, following decades of sharp decline in the Far East, intensifies labor shortages despite high per capita GRP driven by mining.[64] Western sanctions enacted since 2022 have compounded pressures on the gold sector by elevating equipment and reagent costs, curtailing technology imports, and complicating export channels, rendering production margins precarious when costs approach or exceed gold prices.[10] [65] Fisheries face parallel headwinds, mirroring national trends with Russia's overall catch falling 8% to 4.88 million tons in 2024 amid processing and market disruptions.[66] Economic activity rate declined to 70.5% in 2024 from 71.9% the prior year, signaling subdued dynamism.[67] Efforts to mitigate these issues include the 2025 creation of a priority development area offering tax incentives and regulatory relief to spur investments in ship repair, fish processing, logistics, tourism, and mining.[68] [69] Governor Sergei Nosov noted in August 2025 that gross regional product expansion matches national rates, bolstering sustainable contributions via mineral extraction and tax revenues.[6] [70] Urban master plans and infrastructure subsidies aim to enhance connectivity and attract residents, though realization depends on federal funding amid broader fiscal strains.[71]Society and Culture

Cultural Life and Institutions

Magadan functions as the primary cultural center for Magadan Oblast, featuring theaters, libraries, and occasional festivals that sustain artistic engagement amid the region's isolation and severe weather. Local institutions, many rooted in the Soviet period, cater to a populace noted for its strong interest in performing arts and literature.[72][73] The Magadan State Drama Theater, established with its Soviet modernist building completed in 1941, represents the city's inaugural public cultural venue and hosts regular dramatic productions.[74] Complementing this are a puppet theater and the Magadan State Music and Drama Theatre, which provide variety in musical and theatrical offerings, including historical performances dating back to the 1930s.[2][75] The philharmonic society further supports classical music events, fostering a venue for orchestral and choral activities.[2] The Magadan Regional Universal Scientific Library named after A.S. Pushkin, founded on May 22, 1939, serves as the oblast's central repository with an extensive collection exceeding three million volumes, facilitating literary access and cultural programs.[76][77] Cinemas like the Gornyak Cinema on Lenina Avenue offer screenings of films and special broadcasts, maintaining cinematic traditions in the Far East.[78] Festivals enhance the cultural landscape, with the Territory art festival recurring in Magadan since 2017, drawing prominent Russian theater companies and underscoring demand for high-caliber events.[72][79] Additional gatherings, such as the International Festival "Carving Art of the Peoples of the World" held in the city, promote global artisan traditions alongside local fairs and concerts.[80][73]Religious Composition and Practices

The predominant form of organized religion in Magadan is Russian Orthodoxy, administered by the Eparchy of Magadan and Sinegorye of the Russian Orthodox Church, though affiliation and practice remain limited due to the legacy of Soviet-era suppression and the region's remote, industrialized character. No Orthodox churches existed in Magadan prior to 1991, reflecting the atheistic policies of the USSR that dismantled religious infrastructure across the Kolyma region, including during the Gulag period when religious observance was persecuted.[81] Post-Soviet revival efforts led to the construction of several parishes, with the Holy Trinity Cathedral—consecrated by Patriarch Kirill on September 2, 2011, as the largest Orthodox cathedral in Russia's Far East—serving as the eparchial seat and a focal point for services.[82] Practices among Orthodox adherents follow traditional Russian liturgical rites, including Divine Liturgy, veneration of icons, and observance of major feasts such as Pascha (Easter) and Nativity, though attendance is sporadic and influenced by the harsh subarctic climate and small community sizes. The Russian Orthodox Church has portrayed Magadan as historically lacking deep religious roots, attributing this to decades of state-enforced irreligion and population transience from labor camps, which prioritized survival over spiritual continuity.[83] Other active Orthodox sites include the Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh and the Cathedral of the Holy Spirit, which host baptisms, weddings, and memorial services, often tied to remembrance of Gulag victims. A minor Roman Catholic presence persists, primarily among descendants of foreign prisoners in the Soviet camps, with the Church of the Nativity established in 1994 to serve this group; it operates under the Archdiocese of Anchorage, Alaska, rather than Russian Catholic structures, highlighting the diasporic nature of the community. Indigenous Even and Yukaghir populations, comprising less than 2% of Magadan Oblast's residents, retain traces of animistic and shamanistic traditions, though these are largely syncretized with or supplanted by Orthodoxy.[84] Organized Islam, Protestantism, or other faiths have negligible followings, with no registered communities of significant scale reported in the oblast. Overall, self-identified religious adherence hovers below national averages, underscoring persistent secularism shaped by historical trauma and geographic isolation.Memorials, Gulag Legacy, and Public Remembrance

Magadan's historical role as the administrative hub for the Kolyma Gulag camps underscores its enduring legacy of Soviet-era political repression, where prisoners endured extreme cold, forced labor in gold mines, and malnutrition, resulting in massive mortality rates. The city's port served as the primary entry point for deportees transported by ship, with the Kolyma Highway—known as the Road of Bones—constructed largely by inmate labor linking camps to extraction sites. Estimates of deaths in the Kolyma system, based on archival data and survivor accounts, range from hundreds of thousands to over one million, driven by deliberate under-provisioning and punitive conditions rather than mere logistical failures.[37] The Mask of Sorrow monument, unveiled in June 1996, stands as the preeminent site commemorating these victims, designed by Russian-American sculptor Ernst Neizvestny and perched on a hill 3 kilometers from central Magadan. This 15-meter concrete edifice features a colossal human face contorted in anguish, with a prominent tear forming a barred prison window containing a silhouette of an imprisoned figure, evoking the isolation and despair of the camps. A smaller sculpture of a weeping woman at the base represents collective mourning, particularly for families shattered by arbitrary arrests and executions. Funded through public and international donations, the memorial explicitly honors the prisoners who "suffered and died" in the Gulag, countering earlier Soviet glorification of the region's industrialization.[85][86][87] Public remembrance centers on the national Day of Remembrance for Victims of Political Repressions, observed October 30, when locals gather at the Mask of Sorrow for vigils, laying flowers and reading names of the deceased to affirm the human cost of the system. Additional sites include the Serpentinka cemetery outside Magadan, a burial ground for executed prisoners, where databases compiled by historians and former dissident groups document 11,427 identified victims in the region as of recent records. Despite these efforts, commemoration faces constraints in contemporary Russia, where state narratives often frame repressions as excesses rather than inherent to the regime's causal structure of ideological enforcement through terror, leading to selective preservation of sites amid urban development pressures. Independent documentation persists through survivor testimonies and declassified archives, prioritizing empirical victim counts over politicized reinterpretations.[88][89][90]Education and Sports

Education in Magadan primarily consists of general secondary schools and vocational training institutions, aligned with Russia's national system of 11 years of compulsory education divided into primary, basic, and secondary levels.[91] The city hosts specialized schools such as Gymnasium "English," which enrolls students from ages 6.5 to 18 and emphasizes in-depth English language instruction alongside standard curricula.[92] Higher education is dominated by North-Eastern State University (NESU), a public institution enrolling 2,000 to 2,999 students across programs in pedagogy, economics, law, and natural sciences.[93] Formed in 1997 through the merger of the former International Pedagogical University—itself reorganized from the Magadan State Pedagogical Institute in 1992—and the local branch of Khabarovsk State Technical University, NESU focuses on regional needs like resource extraction and environmental studies.[94] The university conducts research activities and maintains accreditation for quality education.[95] Sports infrastructure in Magadan emphasizes indoor facilities due to the subarctic climate, with the Presidential Universal Sports and Health Complex serving as a key venue. Opened in 2025 and funded through federal programs for physical culture development, the complex includes a multi-purpose gymnasium for team sports, an ice arena, and a 25-meter, 8-lane swimming pool.[96][97] President Vladimir Putin visited the facility on August 15, 2025, highlighting its role in promoting public health and youth engagement in sports.[96] Local participation centers on hockey, swimming, and gymnastics, though competitive teams remain limited compared to larger Russian cities.[98]Notable Individuals

Prominent Figures from Magadan

Yelena Välbe, born April 20, 1968, in Magadan, is a former Russian cross-country skier who achieved international prominence, winning five Olympic gold medals between 1992 and 1998, along with 18 world championship titles across various distances and relays.[99] Her career, spanning 1987 to 1997, established her as one of the most decorated athletes in the sport's history, with a total of 72 individual victories in FIS World Cup events.[100] Välbe later served in administrative roles, including as president of the Russian Cross-Country Skiing Federation from 2010 to 2023.[99] Anton Belyaev, born September 18, 1979, in Magadan, is a Russian musician, composer, and producer best known as the frontman of the indie pop band Therr Maitz, which he founded in 2009.[101] The band's music, blending electronic and alternative elements, gained recognition through soundtracks for films like Ice (2018) and performances at major Russian festivals.[101] Belyaev has also contributed to theater productions and received awards such as the Golden Gramophone for his solo work.[101] Sasha Luss, born June 6, 1992, in Magadan, is a model and actress who began her career in Moscow at age 14 before gaining global attention with runway appearances for brands like Chanel and Dior.[102] She transitioned to acting with her lead role in Luc Besson's Anna (2019), portraying a KGB assassin, and has since appeared in films such as Honey Boy (2019).[102] Luss's early relocation from Magadan influenced her path, as she cited the city's isolation in interviews reflecting on her upbringing.[103] Inna Korobkina, born February 23, 1981, in Magadan, is a Russian-Canadian actress and producer who emigrated to Canada in 1991 and debuted in Hollywood with a role in Dawn of the Dead (2004), playing Ana, a nurse surviving a zombie outbreak.[104] Her filmography includes appearances in The Ladies Man (2000) and Russian productions, often portraying strong female leads, with additional work in voice acting and modeling.[104] Korobkina has credited her Magadan roots for fostering resilience amid the region's challenging environment.[104]International Ties

Twin Cities and Partnerships

Magadan maintains formal twin city agreements with several international partners, primarily focused on economic, cultural, and trade cooperation. These partnerships, established through bilateral agreements, reflect the city's emphasis on regional development in Russia's Far East. As of 2024, the official roster includes cities and a district from China, Belarus, the United States, and Bulgaria.[105] The earliest agreement is with Anchorage, Alaska, United States, signed on June 22, 1991, and updated on May 10, 1995, to promote mutual exchanges in various fields. However, in April 2023, the Anchorage Assembly unanimously voted to suspend the relationship in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, though Magadan's municipal records continue to list it without noting the suspension.[105][106] Agreements with Chinese cities emphasize economic ties: Tonghua (Tunhua), Jilin Province, established July 1, 1992 (updated July 14, 2018), and Shuangyashan, Heilongjiang Province, signed July 12, 2013, both targeting trade, investment, and socio-cultural exchanges.[105] In Europe and the post-Soviet sphere, partnerships include Zlatitsa, Bulgaria (September 27, 2012, for general cooperation); Baranovichi, Belarus (May 19, 2018, covering trade, science, technology, and culture); Gomel, Belarus (September 19, 2024, aimed at investment attraction and joint business projects); and the Oktyabrsky District of Minsk, Belarus (2022, for administrative-level cooperation).[105][107]| Twin City/Partner | Country | Establishment Date | Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anchorage | United States | June 22, 1991 (updated 1995) | Mutual exchanges; suspended by U.S. side in 2023[106] |

| Tonghua (Tunhua) | China | July 1, 1992 (updated 2018) | Trade and cultural cooperation |

| Zlatitsa | Bulgaria | September 27, 2012 | General cooperation |

| Shuangyashan | China | July 12, 2013 | Economic and socio-cultural ties |

| Baranovichi | Belarus | May 19, 2018 | Trade, science, technology, culture |

| Oktyabrsky District, Minsk | Belarus | 2022 | Administrative cooperation |

| Gomel | Belarus | September 19, 2024 | Investment and business development[107] |

References

- https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q50073176