Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Metallic mean

View on WikipediaThe metallic mean (also metallic ratio, metallic constant, or noble mean[1]) of a natural number n is a positive real number, denoted here that satisfies the following equivalent characterizations:

- the unique positive real number such that

- the positive root of the quadratic equation

- the number

- the number whose expression as a continued fraction is

Metallic means are (successive) derivations of the golden () and silver ratios (), and share some of their interesting properties. The term "bronze ratio" () (Cf. Golden Age and Olympic Medals) and even metals such as copper () and nickel () are occasionally found in the literature.[2][3][a]

In terms of algebraic number theory, the metallic means are exactly the real quadratic integers that are greater than and have as their norm.

The defining equation of the nth metallic mean is the characteristic equation of a linear recurrence relation of the form It follows that, given such a recurrence the solution can be expressed as

where is the nth metallic mean, and a and b are constants depending only on and Since the inverse of a metallic mean is less than 1, this formula implies that the quotient of two consecutive elements of such a sequence tends to the metallic mean, when k tends to the infinity.

For example, if is the golden ratio. If and the sequence is the Fibonacci sequence, and the above formula is Binet's formula. If one has the Lucas numbers. If the metallic mean is called the silver ratio, and the elements of the sequence starting with and are called the Pell numbers.

Geometry

[edit]

The defining equation of the nth metallic mean induces the following geometrical interpretation.

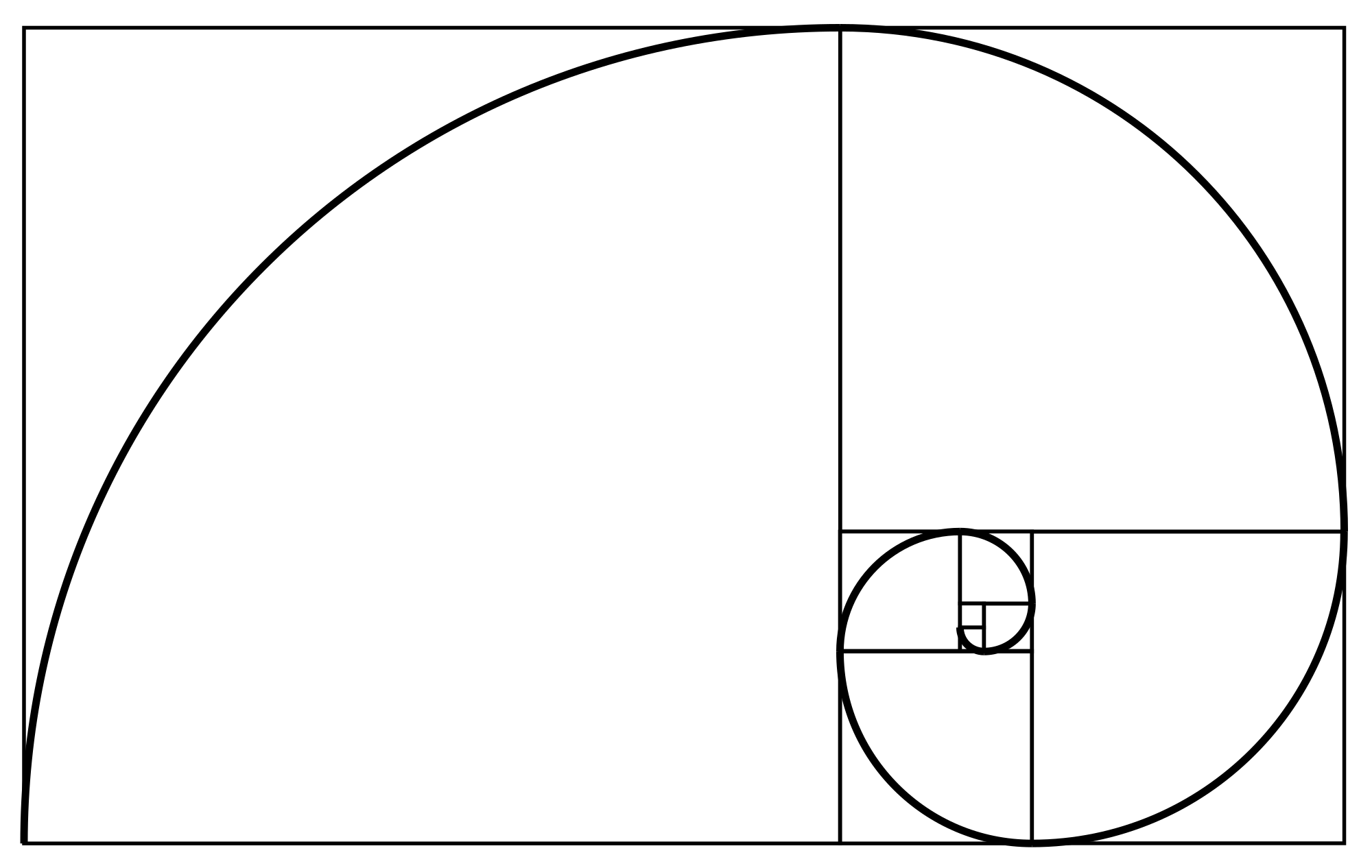

Consider a rectangle such that the ratio of its length L to its width W is the nth metallic ratio. If one remove from this rectangle n squares of side length W, one gets a rectangle similar to the original rectangle; that is, a rectangle with the same ratio of the length to the width (see figures).

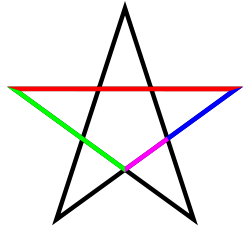

Some metallic means appear as segments in the figure formed by a regular polygon and its diagonals. This is in particular the case for the golden ratio and the pentagon, and for the silver ratio and the octagon; see figures.

Powers

[edit]Denoting by the metallic mean of m one has

where the numbers are defined recursively by the initial conditions K0 = 0 and K1 = 1, and the recurrence relation

Proof: The equality is immediately true for The recurrence relation implies which makes the equality true for Supposing the equality true up to one has

End of the proof.

One has also [citation needed]

The odd powers of a metallic mean are themselves metallic means. More precisely, if n is an odd natural number, then where is defined by the recurrence relation and the initial conditions and

Proof: Let and The definition of metallic means implies that and Let Since if n is odd, the power is a root of So, it remains to prove that is an integer that satisfies the given recurrence relation. This results from the identity

This completes the proof, given that the initial values are easy to verify.

In particular, one has

and, in general,[citation needed]

where

For even powers, things are more complicated. If n is a positive even integer then[citation needed]

Additionally,[citation needed]

For the square of a metallic ratio we have:

where lies strictly between and . Therefore

Generalization

[edit]One may define the metallic mean of a negative integer −n as the positive solution of the equation The metallic mean of −n is the multiplicative inverse of the metallic mean of n:

Another generalization consists of changing the defining equation from to . If

is any root of the equation, one has

The silver mean of m is also given by the integral[4]

Another form of the metallic mean is[4]

Relation to half-angle cotangent

[edit]A tangent half-angle formula gives which can be rewritten as That is, for the positive value of , the metallic mean which is especially meaningful when is a positive integer, as it is with some Pythagorean triangles.

Relation to Pythagorean triples

[edit]

For a primitive Pythagorean triple, a2 + b2 = c2, with positive integers a < b < c that are relatively prime, if the difference between the hypotenuse c and longer leg b is 1, 2 or 8 then the Pythagorean triangle exhibits a metallic mean. Specifically, the cotangent of one quarter of the smaller acute angle of the Pythagorean triangle is a metallic mean.[5]

More precisely, for a primitive Pythagorean triple (a, b, c) with a < b < c, the smaller acute angle α satisfies When c − b ∈ {1, 2, 8}, we will always get that is an integer and that the n-th metallic mean.

The reverse direction also works. For n ≥ 5, the primitive Pythagorean triple that gives the n-th metallic mean is given by (n, n2/4 − 1, n2/4 + 1) if n is a multiple of 4, is given by (n/2, (n2 − 4)/8, (n2 + 4)/8) if n is even but not a multiple of 4, and is given by (4n, n2 − 4, n2 + 4) if n is odd. For example, the primitive Pythagorean triple (20, 21, 29) gives the 5th metallic mean; (3, 4, 5) gives the 6th metallic mean; (28, 45, 53) gives the 7th metallic mean; (8, 15, 17) gives the 8th metallic mean; and so on.

Numerical values

[edit]| First metallic means[6][7] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Ratio | Value | Name |

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1.618033988...[8] | Golden | |

| 2 | 2.414213562...[9] | Silver | |

| 3 | 3.302775637...[10] | Bronze[11] | |

| 4 | 4.236067977...[12] | Copper[11][a] | |

| 5 | 5.192582403...[13] | Nickel[11][a] | |

| 6 | 6.162277660...[14] | ||

| 7 | 7.140054944...[15] | ||

| 8 | 8.123105625...[16] | ||

| 9 | 9.109772228...[17] | ||

| 10 | 10.099019513...[18] | ||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ M. Baake, U. Grimm (2013) Aperiodic order. Vol. 1. A mathematical invitation. With a foreword by Roger Penrose. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 149. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 978-0-521-86991-1.

- ^ de Spinadel, Vera W. (1999). "The metallic means family and multifractal spectra" (PDF). Nonlinear Analysis, Theory, Methods and Applications. 36 (6). Elsevier Science: 721–745.

- ^ de Spinadel, Vera W. (1998). Williams, Kim (ed.). "The Metallic Means and Design". Nexus II: Architecture and Mathematics. Fucecchio (Florence): Edizioni dell'Erba: 141–157.

- ^ a b "Metallic means - OeisWiki". oeis.org. Retrieved 2025-07-31.

- ^ Rajput, Chetansing; Manjunath, Hariprasad (2024). "Metallic means and Pythagorean triples | Notes on Number Theory and Discrete Mathematics". Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Table of Silver means". MathWorld.

- ^ "An Introduction to Continued Fractions: The Silver Means", maths.surrey.ac.uk.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A001622 (Decimal expansion of golden ratio phi (or tau) = (1 + sqrt(5))/2)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ OEIS: A014176, Decimal expansion of the silver mean, 1+sqrt(2).

- ^ OEIS: A098316, Decimal expansion of [3, 3, ...] = (3 + sqrt(13))/2.

- ^ a b c "The Family of Metallic Means".

- ^ OEIS: A098317, Decimal expansion of phi^3 = 2 + sqrt(5).

- ^ OEIS: A098318, Decimal expansion of [5, 5, ...] = (5 + sqrt(29))/2.

- ^ OEIS: A176398, Decimal expansion of 3+sqrt(10).

- ^ OEIS: A176439, Decimal expansion of (7+sqrt(53))/2.

- ^ OEIS: A176458, Decimal expansion of 4+sqrt(17).

- ^ OEIS: A176522, Decimal expansion of (9+sqrt(85))/2.

- ^ OEIS: A176537, Decimal expansion of 5 + sqrt(26).

Further reading

[edit]- Stakhov, Alekseĭ Petrovich (2009). The Mathematics of Harmony: From Euclid to Contemporary Mathematics and Computer Science, p. 228, 231. World Scientific. ISBN 9789812775832.

External links

[edit]- Cristina-Elena Hrețcanu and Mircea Crasmareanu (2013). "Metallic Structures on Riemannian Manifolds", Revista de la Unión Matemática Argentina.

- Rakočević, Miloje M. "Further Generalization of Golden Mean in Relation to Euler's 'Divine' Equation", Arxiv.org.

Metallic mean

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

The metallic mean, also known as the metallic ratio, is a family of positive real numbers parameterized by a positive integer , each defined as the positive root of the quadratic equation .[6] This yields the explicit closed-form expression .[6] Equivalently, each metallic mean satisfies the recursive relation , reflecting a self-similar structure analogous to that of the golden ratio.[7] The family generalizes the golden ratio, which corresponds to and is denoted , historically significant in geometry and aesthetics.[6] For , it is the silver ratio ; for , the bronze ratio ; and higher values follow the pattern of ascending metallic names (e.g., nickel for , copper for ).[6] These naming conventions, extending beyond the golden and silver ratios to encompass the broader family, were introduced by mathematician Vera W. de Spinadel in 1999.[6] Metallic means originate as the dominant eigenvalues of certain 2×2 companion matrices of the form , whose characteristic equation matches the defining quadratic.[7] They also arise as limiting ratios of consecutive terms in linear recurrences generalizing the Fibonacci sequence, such as those defined by with initial conditions , .[4]Basic Properties

The metallic means for positive integers are irrational algebraic numbers of degree 2, as they satisfy the irreducible quadratic equation over the rationals, where the discriminant is not a perfect square (since for ).[8][4] This minimal polynomial establishes as a quadratic irrational. The roots of this minimal polynomial are and its conjugate , satisfying (from the constant term of the polynomial) and thus ; since , it follows that and .[4] This conjugate lies in the interval (-1, 0), ensuring that powers of dominate approximations in associated integer sequences. In the quadratic integer ring (or more precisely, the ring of integers of , which is when ), generates a fundamental unit of norm -1, as its norm .[9] Such units play a key role in solving Pell-like equations in these fields. The metallic means connect to linear recurrence relations of order 2 via the characteristic equation ; the general solution to the recurrence (with positive initial conditions) is for constants , and since , the term becomes negligible for large , so .[10] Specific cases include the Fibonacci sequence for (where ratios approach the golden ratio ), the Pell sequence for (ratios approach the silver ratio ), and the generalized Pell sequence for defined by with , (ratios approach the bronze ratio ).[11][10]Geometric Interpretations

Rectangle Constructions

The geometric construction of the metallic mean of order , denoted , utilizes a self-similar rectangle in which represents the aspect ratio of the longer side to the shorter side. To illustrate this, consider a rectangle with shorter side of length 1 and longer side of length . Along the longer side, squares, each of side length 1, can be removed, as for positive integers . The remaining figure is then a rectangle with dimensions 1 by .[2] The self-similarity arises from the defining quadratic equation for the metallic mean, , which rearranges to . Consequently, the remaining rectangle has sides of length 1 and , yielding an aspect ratio of , identical to that of the original rectangle. This remaining rectangle is scaled by a factor of relative to the initial one, confirming the geometric similarity.[4][2] This removal process can be applied iteratively to the remaining rectangle, generating an infinite sequence of smaller, similar rectangles in a manner that produces an infinite descent. The construction is directly analogous to that of the golden rectangle, where and a single square is removed to yield a similar remainder.[2] Visual representations of this construction, such as diagrams for the silver rectangle () and bronze rectangle (), depict the sequential placement and removal of the squares along the longer side, with the scaled similar rectangle clearly outlined in the remainder. The proof of similarity in each iteration stems from the algebraic relation embedded in the defining equation, ensuring the property holds indefinitely.[2]Polygonal Representations

The metallic means manifest in the geometry of regular polygons through ratios of diagonals to sides, revealing connections between algebraic properties and discrete symmetric figures. In a regular pentagon, the golden ratio equals the ratio of a diagonal to a side.$$] This arises from the chord lengths spanning two vertices versus one, given by . The pentagon's five-fold symmetry underscores the golden ratio's role in classical constructions, such as the five Platonic solids where pentagonal faces appear. For the silver ratio , a regular octagon provides the geometric embedding, where the ratio of the medium diagonal (spanning three vertices) to the side length is exactly .[$$ This corresponds to , highlighting the octagon's eight-fold rotational symmetry and its diagonals' intersections forming silver rectangles internally. The silver ratio also governs the width (distance between parallel sides) to side length ratio in the octagon, equal to . Higher-order metallic means generalize this pattern, appearing in regular polygons with sides as ratios involving combinations of diagonals rather than simple single-diagonal-to-side proportions.$$] For the bronze ratio , such relations occur in the 13-gon through sums or products of diagonal segments from a common vertex, with over 1,700 verified combinations yielding . These configurations involve specific central angles, such as multiples of , where trigonometric identities link the ratios to the metallic mean's defining quadratic equation. No higher metallic mean matches a single diagonal-to-side ratio in any regular polygon, distinguishing them from the golden and silver cases. Metallic means extend to polygonal tilings, particularly aperiodic ones. The silver ratio serves as the inflation factor in the Ammann–Beenker tiling, a quasiperiodic octagonal tiling composed of squares and rhombi that covers the plane without gaps or overlaps, mirroring the self-similar properties of the ratio.[$$ This tiling's eight-fold symmetry parallels the regular octagon's geometry, enabling hierarchical subdivisions scaled by .Algebraic Properties

Powers

The powers of the metallic mean , the positive root of the equation , satisfy a linear recurrence derived from the characteristic equation. Specifically, for , with initial conditions and .[12] This recurrence leads to a closed-form expression involving the associated sequence , defined by , , and for , which generalizes the Fibonacci sequence for and the Pell sequence for . The formula is . For example, when (the silver ratio ), , where 2 and 1 are the second and first terms of the Pell sequence. This expression holds by induction, as it matches the initial conditions and preserves the recurrence.[11][12] A related identity analogous to Cassini's identity for Fibonacci numbers is , which arises from the determinant of the recurrence matrix being -1 and applies to the generalized sequence for any integer . This identity underscores the structural similarities between metallic means and their sequences.[12] Odd powers of metallic means exhibit a notable pattern: , where is the -th term of the Lucas sequence associated with , defined by , , and for . For instance, with (golden ratio) and so , , yielding ; similarly, for and , , yielding . This property highlights how odd powers generate other metallic means within the family.[13] Binet-like formulas for the sequence further connect powers to the metallic mean and its conjugate , where . The formula is , which provides an exact expression and explains the integer nature of through rounding properties. For , this reduces to the classical Binet formula for Fibonacci numbers.[12]Continued Fractions

The metallic mean of order , defined as the positive real solution to the equation , possesses an infinite continued fraction expansion that is purely periodic with period length 1, expressed as .[14] This representation holds for all positive integers , encompassing well-known cases such as the golden mean for () and the silver mean for ().[15] The purely periodic nature arises directly from the defining quadratic equation. Rearranging gives . Substituting the expression for on the right-hand side iteratively produces , confirming the continued fraction form through the self-similar structure inherent to the equation.[14] This derivation leverages the properties of quadratic irrationals, where solutions to such equations yield periodic continued fractions, with the period length of 1 reflecting the simplicity of the recurrence in the metallic mean's minimal polynomial. The convergents of this continued fraction, obtained by truncating the expansion at finite stages, yield the optimal rational approximations to in the sense of providing the closest fractions with denominators up to a given size.[15] These convergents satisfy the standard recurrences for continued fraction approximants: and , with initial conditions , , , .[15] Consequently, the sequences and align with the generalized Fibonacci sequences associated with the metallic mean, where terms follow the linear recurrence (e.g., starting with , for the denominator sequence), and the ratios converge to as .[15] This connection underscores the role of continued fractions in generating sequence-based approximations that capture the algebraic structure of .[14]Generalizations

Negative and Fractional Orders

The generalization of metallic means to negative integer orders involves modifying the defining quadratic equation to account for the sign change in the linear coefficient. For a negative order where is a positive integer, the equation becomes , and the positive root is . This value lies between 0 and 1 and equals the reciprocal of the positive metallic mean for the corresponding positive order , preserving key algebraic properties such as irrationality since is irrational for integer .[16] The negative root of this equation is , and thus where is the negative root for the positive order equation . These negative order means maintain connections to continued fraction expansions and recurrence relations analogous to their positive counterparts, though with inverted magnitudes. For fractional orders, metallic means are extended to rational values (with integers, ) by solving generalized quadratic forms derived from the standard definition, often yielding positive real solutions greater than 1. A notable construction links fractional orders to primitive Pythagorean triples with , where the order is and the metallic mean is .[17] This approach produces integer-valued metallic means for specific families of triples; for instance, in the family generated by parameters , the triple gives and , an integer. Similarly, for rational with , the metallic mean simplifies to the integer , as in the case yielding and from the triple (4, 3, 5).[16] These fractional extensions often preserve irrationality for orders not aligned with such special triples, mirroring the behavior of integer-order metallic means, while establishing recurrence links through associated sequences like generalized Fibonacci polynomials. For example, the metallic mean satisfies a linear recurrence derived from the characteristic equation , enabling connections to broader algebraic structures.[17] Negative fractional orders can be analogously defined using angular representations, where the order for yields metallic ratios solving , with the positive branch providing values interpretable as reciprocals or conjugates of positive fractional cases.[16]Modified Equations

The modified equations for metallic means extend the standard quadratic form by varying the constant term, leading to broader families of quadratic irrationals. The general equation is , where is a positive integer and is a positive parameter, often taken as an integer. The positive root, denoted , is given by This root generalizes the metallic mean, with the case recovering the classical form .[18] Special cases for produce analogs to other notable irrationals. For , the equation yields, for example, the root when , though integer-valued, and for , . These variants link to sequences beyond Fibonacci-like ones, including those with norms differing from .[19] A key property is that lies in the quadratic order of the field , where the ring's units include powers of adjusted for the norm , generalizing the unit structure seen in standard metallic means (where yields norm ). Vera W. de Spinadel's family further broadens this by varying both coefficients and in , with serving as the dominant eigenvalue of the companion matrix associated with the recurrence . This framework encompasses infinite families applicable in geometry and sequences, with .[4]Mathematical Connections

Trigonometric Relations

The metallic means exhibit intriguing connections to trigonometric functions via half-angle identities for the cotangent. Specifically, for a positive integer , if an angle satisfies , then , where denotes the th metallic mean, the positive root of the quadratic equation . This identity arises directly from the standard half-angle formula for cotangent, . Substituting yields . Applying the Pythagorean identity gives , so and (taking the positive root for acute ). Then . Substituting into the half-angle formula produces:Pythagorean Triples

Primitive Pythagorean triples, which are sets of three positive integers (a, b, c) satisfying a² + b² = c² with gcd(a, b, c) = 1 and not all odd, exhibit intriguing connections to metallic means through trigonometric characterizations involving quarter-angles. Specifically, for certain primitive triples where the difference between the hypotenuse c and one leg b is 1, 2, or 8, the cotangent of one-quarter the angle θ between sides b and c equals the nth metallic mean δ_n = (n + √(n² + 4))/2.[17] This relation, cot(θ/4) = δ_n, links the geometric properties of these triples directly to the algebraic structure of metallic means, providing a novel perspective on their generation.[17] A representative example is the primitive triple (20, 21, 29) corresponding to n = 5, where c - b = 8 and δ_5 = (5 + √29)/2 ≈ 5.1926.[17] Here, the angle θ between the leg b = 21 and hypotenuse c = 29 satisfies cot(θ/4) = δ_5, illustrating how the metallic mean embeds within the triangle's angular measures. More generally, such triples can be parametrized using iterative half-angle formulas derived from metallic means. For instance, one family of triples with c - b = 1 is given by (2t + 1, 2t² + 2t, 2t² + 2t + 1), where t relates to successive applications of the metallic mean in angle halving.[17] Similarly, for c - b = 8, the form (4m, m² - 4, m² + 4) arises, with m tied to δ_n through half-angle iterations that propagate the metallic ratio.[17] These parametrizations highlight the role of metallic means in iteratively constructing the integer sides via repeated angle bisections. The proof of this cotangent relation relies on tangent addition formulas applied to half- and quarter-angles in the right triangle. Starting from the tangent of the full angle θ, where tan θ = a/b, successive half-angle formulas yield a quadratic equation in terms of cot(θ/4). Specifically, the identity cot²(θ/4) - 2 cot(θ/2) cot(θ/4) - 1 = 0 emerges, whose positive root is δ_n for the specified differences c - b.[17] This quadratic resolution directly incorporates the metallic mean, demonstrating how the irrationality of δ_n aligns with the integer constraints of primitive triples in these cases.Numerical Aspects

Specific Values

The metallic means for positive integers are given by the exact expression . These values increase monotonically with , and for large , the metallic mean approaches asymptotically, since , yielding . The first few metallic means have traditional names inspired by medal metals: the golden mean for , the silver mean for (also the limiting ratio of consecutive Pell numbers), and the bronze mean for . Higher-order means follow a loose naming convention using other metals, such as the copper mean for and the nickel mean for , though these lack universal standardization beyond the initial trio.[20][21] The table below lists the metallic means for to , with exact expressions and decimal approximations rounded to six places.| Name (if applicable) | Exact Expression | Decimal Approximation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Golden mean | 1.618034 | |

| 2 | Silver mean | 2.414214 | |

| 3 | Bronze mean | 3.302776 | |

| 4 | Copper mean | 4.236068 | |

| 5 | Nickel mean | 5.192582 | |

| 6 | - | 6.162278 | |

| 7 | - | 7.140055 | |

| 8 | - | 8.123106 | |

| 9 | - | 9.109108 | |

| 10 | - | 10.098039 |

![{\displaystyle [n;n,n,n,n,\dots ]=n+{\cfrac {1}{n+{\cfrac {1}{n+{\cfrac {1}{n+{\cfrac {1}{n+\ddots \,}}}}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aacef928564d8ef9feeb99ad23cac3109c3a0f31)

![{\displaystyle S_{m}^{2}=[m{\sqrt {m^{2}+4}}+(m+2)]/2=(p+{\sqrt {p^{2}+4}})/2}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f9adf667465015ff5f9588e7b9fa4fc0fa9a3607)