Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Octagon

View on Wikipedia| Regular octagon | |

|---|---|

A regular octagon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 8 |

| Schläfli symbol | {8}, t{4} |

| Coxeter–Dynkin diagrams | |

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D8), order 2×8 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | 135° |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

| Dual polygon | Self |

In geometry, an octagon (from Ancient Greek ὀκτάγωνον (oktágōnon) 'eight angles') is an eight-sided polygon or 8-gon.

A regular octagon has Schläfli symbol {8}[1] and can also be constructed as a quasiregular truncated square, t{4}, which alternates two types of edges. A truncated octagon, t{8} is a hexadecagon, {16}. A 3D analog of the octagon can be the rhombicuboctahedron with the triangular faces on it like the replaced edges, if one considers the octagon to be a truncated square.

Properties

[edit]

The sum of all the internal angles of any octagon is 1080°. As with all polygons, the external angles total 360°.

If squares are constructed all internally or all externally on the sides of an octagon, then the midpoints of the segments connecting the centers of opposite squares form a quadrilateral that is both equidiagonal and orthodiagonal (that is, whose diagonals are equal in length and at right angles to each other).[2]: Prop. 9

The midpoint octagon of a reference octagon has its eight vertices at the midpoints of the sides of the reference octagon. If squares are constructed all internally or all externally on the sides of the midpoint octagon, then the midpoints of the segments connecting the centers of opposite squares themselves form the vertices of a square.[2]: Prop. 10

Regularity

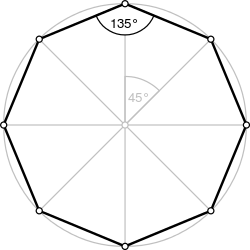

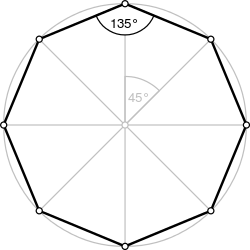

[edit]A regular octagon is a closed figure with sides of the same length and internal angles of the same size. It has eight lines of reflective symmetry and rotational symmetry of order 8. A regular octagon is represented by the Schläfli symbol {8}. The internal angle at each vertex of a regular octagon is 135° ( radians). The central angle is 45° ( radians).

Area

[edit]The area of a regular octagon of side length a is given by

In terms of the circumradius R, the area is

In terms of the apothem r (see also inscribed figure), the area is

These last two coefficients bracket the value of pi, the area of the unit circle.

The area can also be expressed as

where S is the span of the octagon, or the second-shortest diagonal; and a is the length of one of the sides, or bases. This is easily proven if one takes an octagon, draws a square around the outside (making sure that four of the eight sides overlap with the four sides of the square) and then takes the corner triangles (these are 45–45–90 triangles) and places them with right angles pointed inward, forming a square. The edges of this square are each the length of the base.

Given the length of a side a, the span S is

The span, then, is equal to the silver ratio times the side, a.

The area is then as above:

Expressed in terms of the span, the area is

Another simple formula for the area is

More often the span S is known, and the length of the sides, a, is to be determined, as when cutting a square piece of material into a regular octagon. From the above,

The two end lengths e on each side (the leg lengths of the triangles (green in the image) truncated from the square), as well as being may be calculated as

Circumradius and inradius

[edit]The circumradius of the regular octagon in terms of the side length a is[3]

and the inradius is

(that is one-half the silver ratio times the side, a, or one-half the span, S)

The inradius can be calculated from the circumradius as

Diagonality

[edit]The regular octagon, in terms of the side length a, has three different types of diagonals:

- Short diagonal;

- Medium diagonal (also called span or height), which is twice the length of the inradius;

- Long diagonal, which is twice the length of the circumradius.

The formula for each of them follows from the basic principles of geometry. Here are the formulas for their length:[4]

- Short diagonal: ;

- Medium diagonal: ; (silver ratio times a)

- Long diagonal: .

Construction

[edit]

A regular octagon at a given circumcircle may be constructed as follows:

- Draw a circle and a diameter AOE, where O is the center and A, E are points on the circumcircle.

- Draw another diameter GOC, perpendicular to AOE.

- (Note in passing that A,C,E,G are vertices of a square).

- Draw the bisectors of the right angles GOA and EOG, making two more diameters HOD and FOB.

- A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H are the vertices of the octagon.

(The construction is very similar to that of hexadecagon at a given side length.)

A regular octagon can be constructed using a straightedge and a compass, as 8 = 23, a power of two:

The regular octagon can be constructed with meccano bars. Twelve bars of size 4, three bars of size 5 and two bars of size 6 are required.

Each side of a regular octagon subtends half a right angle at the centre of the circle which connects its vertices. Its area can thus be computed as the sum of eight isosceles triangles, leading to the result:

for an octagon of side a.

Standard coordinates

[edit]The coordinates for the vertices of a regular octagon centered at the origin and with side length 2 are:

- (±1, ±(1+√2))

- (±(1+√2), ±1).

Dissectibility

[edit]| 8-cube projection | 24 rhomb dissection | |

|---|---|---|

|

Regular |

Isotoxal |

|

| |

Coxeter states that every zonogon (a 2m-gon whose opposite sides are parallel and of equal length) can be dissected into m(m-1)/2 parallelograms.[5] In particular this is true for regular polygons with evenly many sides, in which case the parallelograms are all rhombi. For the regular octagon, m=4, and it can be divided into 6 rhombs, with one example shown below. This decomposition can be seen as 6 of 24 faces in a Petrie polygon projection plane of the tesseract. The list (sequence A006245 in the OEIS) defines the number of solutions as eight, by the eight orientations of this one dissection. These squares and rhombs are used in the Ammann–Beenker tilings.

Tesseract |

4 rhombs and 2 squares |

Skew

[edit]

A skew octagon is a skew polygon with eight vertices and edges but not existing on the same plane. The interior of such an octagon is not generally defined. A skew zig-zag octagon has vertices alternating between two parallel planes.

A regular skew octagon is vertex-transitive with equal edge lengths. In three dimensions it is a zig-zag skew octagon and can be seen in the vertices and side edges of a square antiprism with the same D4d, [2+,8] symmetry, order 16.

Petrie polygons

[edit]The regular skew octagon is the Petrie polygon for these higher-dimensional regular and uniform polytopes, shown in these skew orthogonal projections of in A7, B4, and D5 Coxeter planes.

| A7 | D5 | B4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

7-simplex |

5-demicube |

16-cell |

Tesseract |

Symmetry

[edit]The regular octagon has Dih8 symmetry, order 16. There are three dihedral subgroups: Dih4, Dih2, and Dih1, and four cyclic subgroups: Z8, Z4, Z2, and Z1, the last implying no symmetry.

r16 | ||

|---|---|---|

d8 |

g8 |

p8 |

d4 |

g4 |

p4 |

d2 |

g2 |

p2 |

a1 | ||

On the regular octagon, there are eleven distinct symmetries. John Conway labels full symmetry as r16.[6] The dihedral symmetries are divided depending on whether they pass through vertices (d for diagonal) or edges (p for perpendiculars) Cyclic symmetries in the middle column are labeled as g for their central gyration orders. Full symmetry of the regular form is r16 and no symmetry is labeled a1.

The most common high symmetry octagons are p8, an isogonal octagon constructed by four mirrors can alternate long and short edges, and d8, an isotoxal octagon constructed with equal edge lengths, but vertices alternating two different internal angles. These two forms are duals of each other and have half the symmetry order of the regular octagon.

Each subgroup symmetry allows one or more degrees of freedom for irregular forms. Only the g8 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can be seen as directed edges.

Use

[edit]

The octagonal shape is used as a design element in architecture. The Dome of the Rock has a characteristic octagonal plan. The Tower of the Winds in Athens is another example of an octagonal structure. The octagonal plan has also been in church architecture such as St. George's Cathedral, Addis Ababa, Basilica of San Vitale (in Ravenna, Italia), Castel del Monte (Apulia, Italia), Florence Baptistery, Zum Friedefürsten Church (Germany) and a number of octagonal churches in Norway. The central space in the Aachen Cathedral, the Carolingian Palatine Chapel, has a regular octagonal floorplan. Uses of octagons in churches also include lesser design elements, such as the octagonal apse of Nidaros Cathedral.

Architects such as John Andrews have used octagonal floor layouts in buildings for functionally separating office areas from building services, such as in the Intelsat Headquarters of Washington or Callam Offices in Canberra.

-

Umbrellas often have an octagonal outline.

-

The famous Bukhara rug design incorporates an octagonal "elephant's foot" motif.

-

Janggi uses octagonal pieces.

-

Japanese lottery machines often have octagonal shape.

-

Famous octagonal gold cup from the Belitung shipwreck

-

Classes at Shimer College are traditionally held around octagonal tables

-

The Labyrinth of the Reims Cathedral with a quasi-octagonal shape.

-

The movement of the analog stick(s) of the Nintendo 64 controller, the GameCube controller, the Wii Nunchuk and the Classic Controller is bounded by an octagonal frame, helping the user aim the stick in cardinal directions while still allowing circular freedom.

-

Chair from A la Ronde, with octagonal seats and backs (set of eight)

Derived figures

[edit]Related polytopes

[edit]The octagon, as a truncated square, is first in a sequence of truncated hypercubes:

| Image |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Octagon | Truncated cube | Truncated tesseract | Truncated 5-cube | Truncated 6-cube | Truncated 7-cube | Truncated 8-cube | |

| Coxeter diagram | ||||||||

| Vertex figure | ( )v( ) |  ( )v{ } |

( )v{3} |

( )v{3,3} |

( )v{3,3,3} | ( )v{3,3,3,3} | ( )v{3,3,3,3,3} |

As an expanded square, it is also first in a sequence of expanded hypercubes:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

... |

| Octagon | Rhombicuboctahedron | Runcinated tesseract | Stericated 5-cube | Pentellated 6-cube | Hexicated 7-cube | Heptellated 8-cube | |

See also

[edit]- Bumper pool

- Hansen's small octagon

- Octagon house

- Octagonal number

- Octagram

- Octahedron, 3D shape with eight faces.

- Oktogon, a major intersection in Budapest, Hungary

- Rub el Hizb (also known as Al Quds Star and as Octa Star), a common motif in Islamic architecture

- Smoothed octagon

References

[edit]- ^ Wenninger, Magnus J. (1974), Polyhedron Models, Cambridge University Press, p. 9, ISBN 9780521098595.

- ^ a b Dao Thanh Oai (2015), "Equilateral triangles and Kiepert perspectors in complex numbers", Forum Geometricorum 15, 105--114. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2015volume15/FG201509index.html Archived 2015-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Weisstein, Eric. "Octagon." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Octagon.html

- ^ Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger B. (2023), A Panoply of Polygons, Dolciani Mathematical Expositions, vol. 58, American Mathematical Society, p. 124, ISBN 9781470471842

- ^ Coxeter, Mathematical recreations and Essays, Thirteenth edition, p.141

- ^ John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, (2008) The Symmetries of Things, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 20, Generalized Schaefli symbols, Types of symmetry of a polygon pp. 275-278)

External links

[edit]- Octagon Calculator

- Definition and properties of an octagon With interactive animation

Octagon

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and History

Definition

An octagon is a polygon with eight sides, eight vertices, and eight edges that connect consecutively to form a closed shape.[7] In general, a polygon is a plane figure consisting of a finite sequence of line segments that close in a loop, with each segment meeting the next at a vertex.[8] Octagons are classified as simple or complex based on their boundary structure. A simple octagon is non-self-intersecting, meaning its edges do not cross each other except at vertices, enclosing a single interior region.[8] In contrast, a complex octagon is self-intersecting, where edges cross to form more intricate shapes, such as star octagons or octagrams.[9] The regular octagon represents the equilateral and equiangular case of this polygon.[10]Etymology and Historical Development

The term "octagon" derives from the Ancient Greek word oktágōnos (ὀκτάγωνος), meaning "eight-angled," composed of oktṓ (ὀκτώ, "eight") and gōnía (γωνία, "angle").[11] This etymology entered Latin as octagōnum before being adopted into English in the late 16th century.[12] In ancient Greek geometry, octagons appeared as early as the 4th century BCE, notably in Euclid's Elements, where Book XII, Proposition 2 describes the construction of a regular octagon by bisecting the circumference of a circle to approximate areas for the method of exhaustion.[13] Euclid's treatment established foundational principles for polygonal approximations, influencing subsequent mathematical explorations of eight-sided figures.[13] During the Islamic Golden Age from the 9th to 12th centuries, octagons gained prominence in geometric tile patterns and architectural designs, with regular octagonal motifs prevailing in Mesopotamian-influenced art since the late 9th century for their symmetry in star polygons and rosettes.[14] Scholars integrated Greek polygonal theory into intricate geometric patterns, using octagons to create repeating designs that symbolized cosmic order in mosques and madrasas.[14] In the Renaissance, octagons featured in architectural plans and practical drawings, as seen in Albrecht Dürer's 1525 treatise Underweysung der Messung mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt, which provided compass-and-straightedge constructions for regular octagons to aid artists and architects in perspective and fortification designs.[15] Dürer's methods bridged theoretical geometry with applied arts, facilitating the use of octagonal forms in structures like centralized churches that evoked harmony between square and circle.Types of Octagons

Regular Octagon

A regular octagon is an eight-sided polygon in which all sides are of equal length and all interior angles measure exactly 135 degrees, making it both equilateral and equiangular.[10] This symmetry distinguishes it as a specific instance of a regular polygon, where the equal sides and angles create a highly uniform shape.[16] By definition, a regular octagon is convex, with every interior angle less than 180 degrees, ensuring that the line segment between any two points inside the polygon lies entirely within it.[17] This convexity contributes to its stability and prevalence in architectural and design applications, such as stop signs and decorative tiles. A regular octagon relates closely to a circle, either inscribed within one—where all vertices touch the circle's circumference—or circumscribed around one, with the circle tangent to the midpoints of all sides.[10] Visually, it can be divided into eight congruent isosceles triangles, each with its apex at the center and base along one side of the octagon, highlighting its radial symmetry.[18] Detailed properties, such as area and perimeter formulas, are explored in later sections.Irregular Octagons

An irregular octagon is a polygon with exactly eight sides and eight vertices, but unlike the regular octagon, its sides and interior angles are not all equal in length or measure.[19] The sum of its interior angles remains fixed at 1080 degrees, calculated as (8-2) × 180 degrees for any octagon.[20] Convex irregular octagons are those where all interior angles are less than 180 degrees, ensuring the polygon does not intersect itself and lies entirely on one side of each of its edges. These octagons exhibit variability in side lengths and angle measures while maintaining convexity, allowing for diverse shapes such as elongated or asymmetrical forms. Concave irregular octagons, also known as non-convex octagons, feature at least one interior angle greater than 180 degrees, causing one or more vertices to "cave in" relative to the overall shape. This reflex angle results in a dented appearance, but the total interior angle sum still equals 1080 degrees, and the figure does not self-intersect. A common example is a rectilinear octagon, where all sides are horizontal or vertical and angles are either 90 degrees or 270 degrees, often seen in architectural floor plans or simplified building outlines with uneven chamfered corners.[21][22] Such octagons appear in complex designs or natural outlines, like irregular bays or stylized icons, where the indentation creates visual depth without crossing boundaries.[23][5] Self-intersecting irregular octagons extend beyond simple polygons by allowing sides to cross each other, forming compound or star-like figures. A prominent example is the octagram, denoted by the Schläfli symbol {8/3}, which connects every third vertex of eight equally spaced points on a circle, resulting in a star-shaped form with intersecting edges and a density of three. These configurations, while irregular in their non-simple boundary, maintain eight distinct sides and are used in geometric art and symbolism.[9][24]Properties of the Regular Octagon

Interior Angles and Side Relations

In a regular octagon, the sum of the interior angles is 1080°, derived from the general formula for polygons where .[16] Each interior angle measures 135°, reflecting the equal distribution of the total sum across all eight vertices.[16] The exterior angle at each vertex is 45°, calculated as , which determines the turning angle when traversing the perimeter.[16] Similarly, the central angle between adjacent vertices is 45°, subtended by the arc connecting two consecutive vertices in the circumscribed circle.[16] For side relations in a regular octagon inscribed in a unit circle (radius ), the side length is the chord subtending the 45° central angle, given by .[16] This side length relates to the diagonals as the shortest chord among them, with longer diagonals corresponding to chords subtending multiples of the 45° central angle (90°, 135°, and 180°), though their explicit lengths are determined separately.Area and Perimeter Formulas

The perimeter of a regular octagon, defined as the total length of its boundary, is calculated by multiplying the side length by the number of sides:This straightforward relation follows from the equilateral nature of the polygon.[25] The area of a regular octagon, representing the enclosed surface, is given by

An equivalent trigonometric form, derived from the general regular polygon area expression, is

These formulas provide exact measures for computational purposes in geometry and engineering applications.[10] To derive the area formula, divide the regular octagon into eight congruent isosceles triangles, each sharing the center as a vertex and having base and equal sides equal to the circumradius. The height of each triangle is the apothem (inradius) , so the area of one triangle is , and the total area is . Substituting yields the standard expression. The inradius thus serves as the essential height in this triangulation approach.[26][10] For cyclic polygons like the regular octagon, an alternative derivation can employ extensions of Brahmagupta's formula for quadrilaterals by decomposing the octagon into cyclic components, though the triangulation method is more direct and commonly used.[27] In comparison to other shapes, the area of a regular octagon with a given perimeter exceeds that of a square with the same perimeter by a factor of approximately 1.207, highlighting the octagon's greater enclosure efficiency for fixed boundary length. This ratio arises from substituting into the area formula and comparing to the square's area .[10][25]

Diagonals and Diagonality

A regular octagon possesses 20 diagonals in total. The number of diagonals in any n-sided polygon is given by the formula ; for , this yields .[28] These diagonals connect non-adjacent vertices and, in a regular octagon of side length , fall into three distinct length categories based on the number of vertices skipped: the short diagonal (skipping one vertex, spanning two sides), the medium diagonal (skipping two vertices, spanning three sides), and the long diagonal (skipping three vertices, which is the diameter). The short diagonal has length , the medium diagonal has length , and the long diagonal has length .[29][10] The ratios of these diagonal lengths to the side length , known as diagonality ratios, are for the short diagonal, for the medium diagonal, and for the long diagonal. These ratios highlight the geometric proportions inherent in the octagon's structure.[29] To derive the diagonal lengths using trigonometry, first determine the circumradius (distance from center to vertex) of the regular octagon: , where . Simplifying, . The length of a diagonal spanning sides (where ) is the chord subtending central angle , given by . For (short diagonal): .[10] For (medium diagonal): , where . Substituting, .[10] For (long diagonal): .[10][29] When all diagonals are drawn, they intersect at various interior points, forming an intricate grid that includes smaller squares, rectangles, and a central smaller regular octagon, along with other polygonal regions. These intersections arise from the octagon's high degree of symmetry, with multiple diagonals crossing at points that divide each other in specific silver ratio proportions in some cases.[30]Circumradius, Inradius, and Apothem

In a regular octagon with side length , the circumradius is the distance from the center to any vertex and the radius of the circumscribed circle passing through all eight vertices. It is given by the formula [10] This expression arises from the isosceles triangle formed by two radii and one side of the octagon, where the central angle is radians; applying the law of sines or the chord length formula yields , which rearranges to the circumradius.[10] The inradius , synonymous with the apothem for regular polygons, is the perpendicular distance from the center to the midpoint of any side and the radius of the inscribed circle tangent to all eight sides. It is expressed as [10] To derive this, consider the right triangle formed by the center, a vertex, and the midpoint of the adjacent side: the hypotenuse is , the leg adjacent to the central half-angle is , and the opposite leg is , so , solving for .[10] Equivalently, , where , giving the ratio .[10]Construction and Representation

Compass and Straightedge Methods

A regular octagon can be constructed using only a compass and straightedge through classical geometric techniques that rely on drawing perpendiculars, angle bisections, and circle intersections. These methods leverage the fact that the central angle of 45° for a regular octagon is constructible, as it is half of the 90° angle formed by perpendicular lines.Basic Method Starting with a Square

This approach begins with constructing a square, which provides the 90° angles necessary for bisection to obtain 45° intervals.- Construct a square ABCD of arbitrary side length using compass and straightedge by drawing perpendicular lines of equal length (using Euclid's Elements, Book I, Propositions 11 (perpendiculars), 31 (parallels), and 15 (equal lengths)).

- Draw the diagonals AC and BD, which intersect at the center O (the diagonals bisect each other [Book I, Proposition 34] and are at right angles due to the square's properties).[31]

- With the compass centered at O and radius OA (distance from center to a vertex), draw the circumcircle passing through A, B, C, and D.

- Bisect the 90° angle AOB at O using the angle bisector construction (Book I, Proposition 9), producing a ray from O at 45° to OA and OB; let this ray intersect the circle at point P.

- Repeat the angle bisection for the other three 90° angles at O (BOC, COD, DOA) to obtain points Q, R, and S on the circle.

- The eight points A, P, B, Q, C, R, D, S form the vertices of the regular octagon; connect them consecutively with the straightedge to complete the figure.

Alternative Method Starting from a Circle

An alternative construction begins directly with a given circle, using perpendiculars and bisections to mark 45° intervals without first drawing a square.- Draw the given circle with center O.

- Mark an arbitrary point A on the circle and draw the radius OA.

- Construct a perpendicular to OA at O (Book I, Proposition 11), intersecting the circle at B, forming a 90° central angle AOB.

- Bisect angle AOB at O (Book I, Proposition 9) to draw a ray intersecting the circle at P (45° from A).

- With the compass set to the length AP (the chord corresponding to 45°), center at P and mark the intersection with the circle in the forward direction to obtain Q; repeat from Q, then from the next point (which will align with B), and continue until eight points are obtained, closing back at A.

- Connect the eight points consecutively to form the regular octagon.

Standard Coordinates

The vertices of a regular octagon centered at the origin with circumradius 1 can be expressed using parametric equations in Cartesian coordinates as for integers . These points align with the unit circle and reflect the octagon's rotational symmetry, with explicit values as follows:| -coordinate | -coordinate | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | ||

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 6 | ||

| 7 |

Dissectibility

A regular octagon can be dissected into eight congruent isosceles triangles by drawing lines from its center to each of the eight vertices; each triangle has an apex angle of 45 degrees at the center and base angles of 67.5 degrees.[35] Another dissection leverages the geometric relation from truncating a square to form the octagon, allowing the regular octagon to be divided into one central square, four rectangles with side ratio , and four congruent smaller squares positioned at the corners.[36] Dissection puzzles involving regular octagons illustrate the Wallace–Bolyai–Gerwien theorem, which states that any two simple polygons of equal area can be dissected into each other using a finite number of polygonal pieces; this provides the theoretical foundation for transforming an octagon into a square, though unlike squaring the circle, such polygonal dissections are always possible. In the context of Hilbert's third problem, which concerns equidissectability of three-dimensional polyhedra and was resolved negatively by Dehn invariants, the two-dimensional case for polygons like the octagon underscores the affirmative result from the earlier theorem. The minimal number of pieces required to dissect a regular octagon into a square of equal area is five, as demonstrated in classic constructions; a specific six-piece dissection also exists, providing an alternative method for equiareal transformation.[37][38]Symmetry

Symmetry Operations

A regular octagon exhibits eight rotational symmetries, achieved by rotating the figure around its center by multiples of 45°: specifically, 0° (the identity transformation), 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, and 315°. These operations map each vertex to another vertex and each side to another side, preserving the octagon's regularity and orientation.[10][39] Complementing the rotations are eight reflection symmetries, each defined by reflection across one of eight distinct axes passing through the center. Four axes connect pairs of opposite vertices, aligning with the longest diagonals of the octagon, while the remaining four axes pass through the midpoints of pairs of opposite sides, aligning with the directions perpendicular to those sides. These reflections reverse the orientation but maintain the overall shape, dividing the octagon into congruent mirror-image halves along each axis.[10][40] Together, these eight rotations and eight reflections constitute the full set of 16 symmetry operations of the regular octagon, forming its dihedral symmetry group.[39] The axes of reflection are evenly spaced every 22.5° around the center, alternating between vertex-to-vertex and midpoint-to-midpoint types, which ensures comprehensive coverage of the figure's bilateral symmetries.[10]Dihedral Group D8

The dihedral group , also known as the dihedral group of order 16, is the symmetry group of the regular octagon, consisting of 8 rotations and 8 reflections. It is generated by a rotation by around the center and a reflection across an axis of symmetry through two opposite vertices, satisfying the relations , , and .[41] The standard presentation of is . This presentation captures the full algebraic structure, where the rotation subgroup is normal and the reflections conjugate rotations to their inverses.[41] Key subgroups of include the cyclic subgroup of order 8 generated by rotations, which is normal and index 2, and several Klein four-groups (isomorphic to ), such as (central 180° rotation with reflections over vertex axes) and (with reflections over edge midpoints). These Klein four-groups arise from pairs of perpendicular reflection axes and the identity with the 180° rotation. admits a faithful irreducible representation in , the group of 2×2 invertible real matrices, acting on the plane. The rotation is represented by the matrix while a reflection (across the x-axis, assuming alignment) is Other reflections are conjugates thereof, preserving the octagon's position. This representation embeds as orientation-preserving and -reversing isometries.[42] The structure of relates to the dihedral group of the square through doubled angular resolution, where rotations occur at 45° intervals instead of 90°, effectively refining the square's symmetries while maintaining the semidirect product form .[41]Skew Octagons

Definition and Properties

A skew octagon is a closed polygonal chain consisting of eight edges whose vertices do not all lie in the same plane, embedded in three-dimensional Euclidean space or higher dimensions, while still forming a closed loop.[43] This distinguishes it from planar octagons, as the non-coplanarity allows for spatial extensions that prevent a simple two-dimensional embedding.[43] In contrast to their planar counterparts, skew octagons lack traditionally defined interior angles, as the absence of a coplanar structure eliminates a well-defined interior region for angle measurement at vertices. Instead, their geometric properties emphasize equal edge lengths in the regular case and the twists between consecutive edges, characterized by the angle between the planes formed by successive triplets of vertices. For regular skew octagons, all edges are congruent, and the angles between adjacent edges are identical, ensuring isogonal symmetry. Regular skew octagons in three dimensions typically manifest as zigzag or helical forms, with vertices alternating between two parallel planes to create a non-planar, antiprismatic configuration. These structures introduce torsion absent in planar polygons, quantifying the out-of-plane twisting through the relative orientation of edge directions, though discrete measures like link torsion replace continuous curvature concepts from space curves. Skew octagons relate to uniform polyhedra, where they serve as girdles—equatorial skew polygons—or appear in traversals like Petrie polygons that weave through faces without three consecutive edges coplanar.[44]Petrie Polygons

Petrie polygons, named after mathematician John Flinders Petrie who recognized their structural importance in regular polyhedra during the 1920s, represent a key concept in the geometry of uniform polytopes.[45] These skew polygons arise from Petrie paths, which are closed sequences of edges in a uniform polytope such that every two consecutive edges lie on a common face, but no three do, effectively alternating between adjacent faces.[44] This definition extends Petrie's original observations to higher dimensions, as formalized by H. S. M. Coxeter in his classification of uniform polytopes.[46] In four-dimensional uniform polytopes, Petrie paths specifically yield skew octagons in cases like the tesseract {4,3,3}. For instance, the tesseract's Petrie polygon traces eight edges, connecting eight of its 16 vertices in a non-planar cycle that skips across cubic cells.[44] Similarly, the 16-cell {3,3,4}, dual to the tesseract, also features a skew octagonal Petrie polygon, highlighting the symmetry shared between dual polytopes.[47] These skew octagons exhibit uniform edge lengths matching the polytope's edge size but are inherently non-planar, embedding in 4D space without lying in a single hyperplane. Their density, a measure of how the polygon intersects itself in projections or embeddings, is typically 1 for convex polytopes like the tesseract, indicating a simple closed path without self-overlaps in the polytope's skeleton.[47] Vertex figures along the Petrie path correspond to the polytope's local structure, such as triangular or square arrangements at each vertex, which aid in visualizing the polytope's rotational symmetries.[44] Coxeter incorporated these polygons into his broader framework for enumerating uniform polytopes, using them to denote additional symmetry parameters in notations like {p, q, r | 2}.[46]Applications

Architectural and Design Uses

The Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence, constructed in the 11th century, exemplifies early use of an octagonal plan in Christian architecture, featuring an octagonal structure measuring 25.6 meters across with an exterior clad in white and green marble.[48] This design allowed for a compact, domed interior space that integrated seamlessly with surrounding structures like the Florence Cathedral.[49] In modern applications, the octagonal shape has been standardized for traffic control devices, notably the stop sign, which adopted its distinctive red octagon form through the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) in 1954, following earlier implementations of the octagonal outline in 1935 for enhanced visibility and quick recognition by drivers.[50] The unique eight-sided profile distinguishes it from other road signs, contributing to its effectiveness in regulatory contexts across the United States.[51] Octagons appear prominently in decorative design traditions, such as the girih tile patterns in Islamic architecture, where sets of five geometric tiles—including those derived from octagrams—have been used since the 13th century to create intricate, interlocking strapwork motifs on walls and floors.[52] These patterns, often incorporating octagonal elements, adorn structures like mosques and madrasas, providing both aesthetic symmetry and structural repetition.[53] During the Victorian era, octagonal floor plans gained popularity in residential architecture, particularly in the United States and Europe, as promoted in Orson Squire Fowler's 1848 treatise A Home for All, which advocated for octagon houses due to their efficient use of space and natural light.[54] Examples include homes with central octagonal rooms branching into rectangular spaces, offering versatile layouts for living areas.[55] A key advantage of octagonal designs in architecture and layout is their spatial efficiency; for the same perimeter, a regular octagon encloses approximately 20% more area than a square, allowing for greater interior volume in compact footprints.[56] This property, combined with the shape's inherent symmetry, enhances aesthetic appeal in both structural and ornamental contexts.[54]Symbolic and Cultural Significance

The octagon holds profound symbolic meaning across various cultures, often tied to the number eight, which represents renewal, infinity, and balance. In Christian architecture, particularly in baptismal fonts, the eight-sided form symbolizes resurrection and new life, evoking the "eighth day" beyond the seven days of creation, as seen in early church designs where the octagon mediates between the earthly square and the heavenly circle.[57][58] In Eastern traditions, the octagon embodies spiritual paths and harmony. Buddhism associates the shape with the Noble Eightfold Path, a core teaching for enlightenment, sometimes reflected in octagonal platforms like the bodhimanda under the Bodhi tree, symbolizing structured progression toward infinity and liberation from suffering.[59] In Taoism, the Bagua—an octagonal arrangement of eight trigrams—represents cosmic balance and the interplay of yin and yang forces, mapping interconnected aspects of reality for philosophical and divinatory purposes.[60][61] Culturally, the octagon appears in heraldry as the "escutcheon octangular" or "octagon ployé," a modified lozenge shape used for displaying arms, particularly in feminine heraldry, providing a balanced frame for charges that echoes medieval shield adaptations.[62] Among some Native American traditions, such as those incorporating expanded medicine wheels, eight directions (including cardinal and intercardinal points) symbolize comprehensive life cycles, seasons, and spiritual guidance, fostering holistic interconnectedness with nature.[63][64] In art, the octagon inspires intricate designs that highlight symmetry and illusion. M.C. Escher incorporated octagonal tessellations in works like Circle Limit III (1959), using hyperbolic geometry to create infinite patterns of fish and shapes, demonstrating the form's capacity for visual depth and mathematical harmony.[65] Japanese origami traditions feature octagonal models, such as the "tato" or octagon box, folded from square paper to form practical yet elegant containers, blending geometric precision with cultural aesthetics of simplicity and utility.[66] Modern uses extend this symbolism into recreation and numerology. In tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons, introduced in the 1970s, the eight-sided die (d8) generates random outcomes for character actions, becoming an iconic tool that embodies chance and narrative balance within gaming communities.[67] In Chinese culture, the number eight is considered auspicious, pronounced "ba" akin to "prosper," influencing designs like octagonal pagodas to invoke wealth, protection, and eternal fortune.[68][69]Related Figures

Derived Polygons

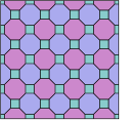

The truncated octagon is a 16-sided polygon derived from a regular octagon by cutting off each vertex, thereby replacing the vertices with new edges while shortening the original sides. This process removes an isosceles triangle at each vertex, with the base of the triangle becoming the new edge. In the general case, the resulting figure has alternating side lengths between the residual original sides and the new truncation edges; for a uniform truncation where these lengths are equalized, it becomes a regular hexadecagon. This 2D operation parallels the truncation used in Archimedean solids, emphasizing edge and vertex uniformity.[70] Rectification of a regular octagon involves truncating the vertices down to the midpoints of the adjacent edges, effectively connecting these midpoints to form a new polygon. The result is a smaller regular octagon, rotated by 22.5 degrees relative to the original and scaled by a factor related to the apothem. This figure preserves the octagonal symmetry and can be seen as the Varignon polygon of the original octagon. In contexts extending to 3D analogues, the rectification relates to projections of the cuboctahedron (the rectification of the octahedron or cube) or the structure of an octagonal antiprism, where 2D cross-sections exhibit similar rectified octagonal forms.[71] The stellated form of the octagon is the octagram, a compound star polygon represented by the Schläfli symbol {8/3}. It is constructed by extending the sides of the regular octagon until they intersect, connecting every third vertex out of eight points equally spaced on a circle. This self-intersecting, non-convex figure has eight equal edges and rotational symmetry of order eight, often appearing in symbolic designs due to its star-like appearance. Unlike the convex octagon, the octagram encloses a central octagonal region surrounded by eight triangular points.[72] Chamfering a regular octagon produces a beveled version by cutting off the corners with straight lines, introducing short new edges at each vertex while preserving the overall octagonal outline. The resulting 16-gon features the original eight sides slightly offset inward or outward, connected by the chamfer segments, which smooth the sharp vertices without fully truncating to midpoints. This derivation enhances the polygon's usability in manufacturing and design by reducing stress concentrations at corners, yielding a polygon with two distinct side length types: the chamfered segments and the modified original sides.[73] Regular octagons feature prominently in semiregular tilings of the Euclidean plane, such as the truncated square tiling with vertex configuration (4.8.8), where one regular square and two regular octagons meet at each vertex. This tessellation, also known as the octagonal-square tessellation, covers the plane periodically without gaps or overlaps, demonstrating the compatibility of octagonal angles (135 degrees) with squares in a balanced arrangement. The tiling arises from truncating a square tiling and exemplifies how derived octagonal elements integrate into larger geometric patterns.[74]Octagonal Polytopes

Octagonal polytopes are higher-dimensional geometric figures that incorporate regular octagons as faces or structural elements, extending the properties of the octagon beyond two dimensions into polyhedral and polychoral frameworks. These polytopes maintain symmetry through vertex-transitivity in uniform cases, where all vertices are equivalent under the figure's symmetry group, and faces remain regular polygons. In three dimensions, octagonal polytopes primarily manifest as prisms and pyramids with octagonal bases, while uniform polyhedra like Archimedean solids feature octagons alongside other regular faces. Higher-dimensional examples include prismatic polychora and hyperbolic honeycombs derived from octagonal tilings.[75] The octagonal prism is a uniform polyhedron consisting of two parallel regular octagonal bases connected by eight square lateral faces, resulting in 10 faces, 24 edges, and 16 vertices overall. Each vertex is incident to one octagon and two squares, ensuring uniform symmetry under the dihedral group D_{8h}. Its dual is a canonical 8-sided trapezohedron. In contrast, the octagonal pyramid features a single regular octagonal base and eight isosceles triangular lateral faces meeting at an apex, yielding 9 faces, 16 edges, and 9 vertices; this non-uniform polyhedron serves as a fundamental building block for more complex structures.[76][77][78] Among uniform polyhedra, several Archimedean solids incorporate regular octagonal faces. The truncated cube, an Archimedean solid, has 14 faces comprising 8 equilateral triangles and 6 regular octagons, with 36 edges and 24 vertices; truncation of the cube replaces original faces with octagons while introducing triangles at vertices. The truncated cuboctahedron, also known as the great rhombicuboctahedron, includes 26 faces: 12 squares, 8 regular hexagons, and 6 regular octagons, alongside 72 edges and 48 vertices, derived from truncating and rectifying a cuboctahedron.[79][80] The octahedral cupola, a Johnson solid (J4), features one regular octagon, one hexagon, eight triangles, and four squares as faces. In four dimensions, octagonal polytopes appear in uniform polychora that include octagonal elements as 2-faces or within cellular structures. The octagonal-tessaractic duoprism, a uniform prismatic polychoron denoted as {8}×{4}, comprises 12 cells: 8 cubic cells (from square prisms) and 4 octagonal prism cells, with octagons serving as a subset of its 8 octagonal 2-faces among 36 square 2-faces, totaling 64 edges and 32 vertices. This construction arises from the Cartesian product of a regular octagon and a square, yielding vertex-transitive symmetry. More complex uniform polychora, such as those with truncated cube cells like the truncated tesseract, inherit octagonal faces from their 3D components.[81] In hyperbolic geometry, octagonal tilings extend to higher-dimensional honeycombs incorporating octagons as faces. The octagonal tiling {8,3}, a regular hyperbolic tessellation with three octagons meeting at each vertex, forms the basis for paracompact hyperbolic 3-honeycombs like the order-4 octagonal honeycomb, where infinite apeirohedral cells feature octagonal facets. In four dimensions, the octagonal duoprismatic tetracomb, a uniform hyperbolic 4-honeycomb, consists of octagonal duoprisms as cells, with 288 facets meeting at each vertex and extensive octagonal 2-faces propagating through its infinite structure. These hyperbolic polytopes demonstrate how octagonal symmetry enables non-Euclidean space-filling arrangements beyond compact forms.[82]References

- https://groupprops.subwiki.org/wiki/Dihedral_group:D8

- https://groupprops.subwiki.org/wiki/Linear_representation_theory_of_dihedral_group:D8