Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

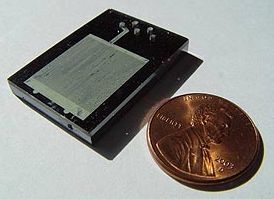

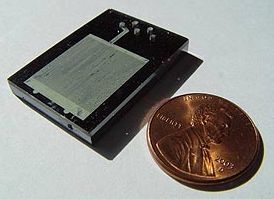

Microreactor

View on Wikipedia

A microreactor or microstructured reactor or microchannel reactor is a device in which chemical reactions take place in a confinement with typical lateral dimensions below 1 mm; the most typical form of such confinement are microchannels.[1][2] Microreactors are studied in the field of micro process engineering, together with other devices (such as micro heat exchangers) in which physical processes occur. The microreactor is usually a continuous flow reactor (contrast with/to a batch reactor). Microreactors can offer many advantages over conventional scale reactors, including improvements in energy efficiency, reaction speed and yield, safety, reliability, scalability, on-site/on-demand production, and a much finer degree of process control.

History

[edit]Gas-phase microreactors have a long history but those involving liquids started to appear in the late 1990s.[1] Static micro mixers as split-and-recombine structures[3] became particular important for micro reaction technology. Chip-based flow thermocylers for PCR were early examples of thermal microreactors for liquid processes.[4][5][6] Other examples are micro flow-through chip calorimeters[7][8]. One of the first microreactors with embedded high performance heat exchangers were made in the early 1990s by the Central Experimentation Department (Hauptabteilung Versuchstechnik, HVT) of Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe[9] in Germany, using mechanical micromachining techniques that were a spinoff from the manufacture of separation nozzles for uranium enrichment.[9] As research on nuclear technology was drastically reduced in Germany, microstructured heat exchangers were investigated for their application in handling highly exothermic and dangerous chemical reactions. This new concept, known by names as microreaction technology or micro process engineering, was further developed by various research institutions. An early example from 1997 involved that of azo couplings in a pyrex reactor with channel dimensions 90 micrometres deep and 190 micrometres wide.[1]

Benefits

[edit]Using microreactors is somewhat different from using a glass vessel. These reactors may be a valuable tool in the hands of an experienced chemist or reaction engineer:

- Microreactors typically have heat exchange coefficients of at least 1 megawatt per cubic meter per kelvin, up to 500 MW m−3 K−1 vs. a few kilowatts in conventional glassware (1 L flask ~10 kW m−3 K−1). Thus, microreactors can remove heat much more efficiently than vessels and even critical reactions such as nitrations can be performed safely at high temperatures.[10] Hot spot temperatures as well as the duration of high temperature exposition due to exothermicity decreases remarkably. Thus, microreactors may allow better kinetic investigations, because local temperature gradients affecting reaction rates are much smaller than in any batch vessel. Heating and cooling a microreactor is also much quicker and operating temperatures can be as low as −100 °C. As a result of the superior heat transfer, reaction temperatures may be much higher than in conventional batch-reactors. Many low temperature reactions as organo-metal chemistry can be performed in microreactors at temperatures of −10 °C rather than −50 °C to −78 °C as in laboratory glassware equipment.

- Microreactors are normally operated continuously. This allows the subsequent processing of unstable intermediates and avoids typical batch workup delays. Especially low temperature chemistry with reaction times in the millisecond to second range are no longer stored for hours until dosing of reagents is finished and the next reaction step may be performed. This rapid work up avoids decay of precious intermediates and often allows better selectivities.[11]

- Continuous operation and mixing causes a very different concentration profile when compared with a batch process. In a batch, reagent A is filled in and reagent B is slowly added. Thus, B encounters initially a high excess of A. In a microreactor, A and B are mixed nearly instantly and B won't be exposed to a large excess of A. This may be an advantage or disadvantage depending on the reaction mechanism - it is important to be aware of such different concentration profiles.

- Although a bench-top microreactor can synthesize chemicals only in small quantities, scale-up to industrial volumes is simply a process of multiplying the number of microchannels. In contrast, batch processes too often perform well on R&D bench-top level but fail at batch pilot plant level.[12]

- Pressurisation of materials within microreactors (and associated components) is generally easier than with traditional batch reactors. This allows reactions to be increased in rate by raising the temperature beyond the boiling point of the solvent. This, although typical Arrhenius behaviour, is more easily facilitated in microreactors and should be considered a key advantage. Pressurisation may also allow dissolution of reactant gasses within the flow stream.

Challenges

[edit]- Although there have been reactors made for handling particles, microreactors generally do not tolerate particulates well, often clogging. Clogging has been identified by a number of researchers as the biggest hurdle for microreactors being widely accepted as a beneficial alternative to batch reactors.[13] So far, the so-called microjetreactor[14] is free of clogging by precipitating products. Gas evolved may also shorten the residence time of reagents as volume is not constant during the reaction. This may be prevented by application of pressure.

- Mechanical pumping may generate a pulsating flow which can be disadvantageous. Much work has been devoted to development of pumps with low pulsation. A continuous flow solution is electroosmotic flow (EOF).

- The logistics issue and enhanced pressure drop across microreactor limits its applicability in large-scale production units. However, clean solutions are handled well in microreactors.[15]

- The scale-up of production rates and leakage are quite challenging in case of microreactor. Recently, so called nanoparticle immobilized reactors are developed to solve logistics and scale-up issues, associated with the microreactors.[16]

- Typically, reactions performing very well in a microreactor encounter many problems in vessels, especially when scaling up. Often, the high area to volume ratio and the uniform residence time cannot easily be scaled.

- Corrosion imposes a bigger issue in microreactors because area to volume ratio is high. Degradation of few μm may go unnoticed in conventional vessels. As typical inner dimensions of channels are in the same order of magnitude, characteristics may be altered significantly.

T reactors

[edit]One of the simplest forms of a microreactor is a 'T' reactor. A 'T' shape is etched into a plate with a depth that may be 40 micrometres and a width of 100 micrometres: the etched path is turned into a tube by sealing a flat plate over the top of the etched groove. The cover plate has three holes that align to the top-left, top-right, and bottom of the 'T' so that fluids can be added and removed. A solution of reagent 'A' is pumped into the top left of the 'T' and solution 'B' is pumped into the top right of the 'T'. If the pumping rate is the same, the components meet at the top of the vertical part of the 'T' and begin to mix and react as they go down the trunk of the 'T'. A solution of product is removed at the base of the 'T'.

Applications

[edit]

Synthesis

[edit]Microreactors can be used to synthesise material more effectively than current batch techniques allow. The benefits here are primarily enabled by the mass transfer, thermodynamics, and high surface area to volume ratio environment as well as engineering advantages in handling unstable intermediates. Microreactors are applied in combination with photochemistry, electrosynthesis, multicomponent reactions and polymerization (for example that of butyl acrylate). It can involve liquid-liquid systems but also solid-liquid systems with for example the channel walls coated with a heterogeneous catalyst. Synthesis is also combined with online purification of the product.[1] Following green chemistry principles, microreactors can be used to synthesize and purify extremely reactive Organometallic Compounds for ALD and CVD applications, with improved safety in operations and higher purity products.[17][18]

In microreactor studies a Knoevenagel condensation[19] was performed with the channel coated with a zeolite catalyst layer which also serves to remove water generated in the reaction. The same reaction was performed in a microreactor covered by polymer brushes.[20]

A Suzuki reaction was examined in another study[21] with a palladium catalyst confined in a polymer network of polyacrylamide and a triarylphosphine formed by interfacial polymerization:

The combustion of propane was demonstrated to occur at temperatures as low as 300 °C in a microchannel setup filled up with an aluminum oxide lattice coated with a platinum / molybdenum catalyst:[22]

Enzyme catalyzed polymer synthesis

[edit]Enzymes immobilized on solid supports are increasingly used for greener, more sustainable chemical transformation processes. > enabled to perform heterogeneous reactions in continuous mode, in organic media, and at elevated temperatures. Using microreactors, enabled faster polymerization and higher molecular mass compared to using batch reactors. It is evident that similar microreactor based platforms can readily be extended to other enzyme-based systems, for example, high-throughput screening of new enzymes and to precision measurements of new processes where continuous flow mode is preferred. This is the first reported demonstration of a solid supported enzyme-catalyzed polymerization reaction in continuous mode.

Analysis

[edit]Microreactors can also enable experiments to be performed at a far lower scale and far higher experimental rates than currently possible in batch production, while not collecting the physical experimental output. The benefits here are primarily derived from the low operating scale, and the integration of the required sensor technologies to allow high quality understanding of an experiment. The integration of the required synthesis, purification and analytical capabilities is impractical when operating outside of a microfluidic context.

NMR

[edit]Researchers at the Radboud University Nijmegen and Twente University, the Netherlands, have developed a microfluidic high-resolution NMR flow probe. They have shown a model reaction being followed in real-time. The combination of the uncompromised (sub-Hz) resolution and a low sample volume can prove to be a valuable tool for flow chemistry.[23]

Infrared spectroscopy

[edit]Mettler Toledo and Bruker Optics offer dedicated equipment for monitoring, with attenuated total reflectance spectrometry (ATR spectrometry) in microreaction setups. The former has been demonstrated for reaction monitoring.[24] The latter has been successfully used for reaction monitoring[25] and determining dispersion characteristics[26] of a microreactor.

Academic research

[edit]Microreactors, and more generally, micro process engineering, are the subject of worldwide academic research. A prominent recurring conference is IMRET, the International Conference on Microreaction Technology. Microreactors and micro process engineering have also been featured in dedicated sessions of other conferences, such as the Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE), or the International Symposia on Chemical Reaction Engineering (ISCRE). Research is now also conducted at various academic institutions around the world, e.g. at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon, at University of California, Berkeley in Berkeley, California in the United States, at the EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland, at Eindhoven University of Technology in Eindhoven, at Radboud University Nijmegen in Nijmegen, Netherlands and at the LIPHT of Université de Strasbourg in Strasbourg and LGPC of the University of Lyon, CPE Lyon, France and at KU Leuven, Belgium.

Market structure

[edit]

The market for microreactors can be segmented based on customer objectives, into turnkey, modular, and bespoke systems.

Turnkey (ready to run) systems are being used where the application environment stands to benefit from new chemical synthesis schemes, enhanced investigational throughput of up to approximately 10 - 100 experiments per day (depends on reaction time) and reaction subsystem, and actual synthesis conduct at scales ranging from 10 milligrams per experiment to triple digit tons per year (continuous operation of a reactor battery).

Modular (open) systems are serving the niche for investigations on continuous process engineering lay-outs, where a measurable process advantage over the use of standardized equipment is anticipated by chemical engineers. Multiple process lay-outs can be rapidly assembled and chemical process results obtained on a scale ranging from several grams per experiment up to approximately 100 kg at a moderate number of experiments per day (3-15). A secondary transfer of engineering findings in the context of a plant engineering exercise (scale-out) then provides target capacity of typically single product dedicated plants. This mimics the success of engineering contractors for the petro-chemical process industry.

With dedicated developments, manufacturers of microstructured components are mostly commercial development partners to scientists in search of novel synthesis technologies. Such development partners typically excel in the set-up of comprehensive investigation and supply schemes, to model a desired contacting pattern or spatial arrangement of matter. To do so they predominantly offer information from proprietary integrated modeling systems that combine computational fluid dynamics with thermokinetic modelling. Moreover, as a rule, such development partners establish the overall application analytics to the point where the critical initial hypothesis can be validated and further confined.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Watts, Paul; Wiles, Charlotte (2007). "Recent advances in synthetic micro reaction technology". Chem. Commun. (5): 443–467. doi:10.1039/b609428g. PMID 17252096.

- ^ Seelam, P.K.; Huuhtanen, M.; Keiski, R.L. (2013). "Microreactors and membrane microreactors: Fabrication and applications". Handbook of Membrane Reactors. pp. 188–235. doi:10.1533/9780857097347.1.188. ISBN 978-0-85709-415-5.

- ^ N. Schwesinger et al. J. Micromech. Microeng. 6 (1996), 99-102

- ^ V. Baier et al.: Miniaturized Flow Thermocycler (WO-9610456-A1; DE 4435107 C1 (30.9.1994/4.4.1996))

- ^ M.U. Kopp et al., Science 280 (1998), 1046–1048

- ^ I. Schneegaß et al., Lab Chip 1 (2001), 42–49

- ^ J.M. Köhler, M. Zieren, Thermochim. Acta, 310 (1998) 25–35

- ^ V. Baier et al. Sensors and Actuators A Physical 123 (2005), 354-359

- ^ a b Schubert, K.; Brandner, J.; Fichtner, M.; Linder, G.; Schygulla, U.; Wenka, A. (January 2001). "Microstructure Devices for Applications in Thermal and Chemical Process Engineering". Microscale Thermophysical Engineering. 5 (1): 17–39. doi:10.1080/108939501300005358.

- ^ Roberge, D. M.; Ducry, L.; Bieler, N.; Cretton, P.; Zimmermann, B. (March 2005). "Microreactor Technology: A Revolution for the Fine Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industries?". Chemical Engineering & Technology. 28 (3): 318–323. doi:10.1002/ceat.200407128.

- ^ Schwalbe, Thomas; Autze, Volker; Wille, Gregor (November 2002). "Chemical Synthesis in Microreactors". CHIMIA. 56 (11): 636. doi:10.2533/000942902777679984.

- ^ Schwalbe, Thomas; Autze, Volker; Hohmann, Michael; Stirner, Wolfgang (May 2004). "Novel Innovation Systems for a Cellular Approach to Continuous Process Chemistry from Discovery to Market". Organic Process Research & Development. 8 (3): 440–454. doi:10.1021/op049970n.

- ^ Kumar, Y.; Jaiswal, P.; Panda, D.; Nigam, K.D.P.; Biswas, K.G. (January 2022). "A critical review on nanoparticle-assisted mass transfer and kinetic study of biphasic systems in millimeter-sized conduits". Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification. 170 108675. Bibcode:2022CEPPI.17008675K. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2021.108675.

- ^ Wille, Ch; Gabski, H.-P; Haller, Th; Kim, H; Unverdorben, L; Winter, R (August 2004). "Synthesis of pigments in a three-stage microreactor pilot plant—an experimental technical report". Chemical Engineering Journal. 101 (1–3): 179–185. Bibcode:2004ChEnJ.101..179W. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2003.11.007. and literature cited therein

- ^ Kumar, Y.; Jaiswal, P.; Panda, D.; Nigam, K.D.P.; Biswas, K.G. (January 2022). "A critical review on nanoparticle-assisted mass transfer and kinetic study of biphasic systems in millimeter-sized conduits". Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification. 170 108675. Bibcode:2022CEPPI.17008675K. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2021.108675.

- ^ Jaiswal, Pooja; Kumar, Yogendra; Shukla, Raman; Nigam, K. D. P.; Panda, Debashis; Guha Biswas, Koushik (16 March 2022). "Covalently Immobilized Nickel Nanoparticles Reinforce Augmentation of Mass Transfer in Millichannels for Two-Phase Flow Systems". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 61 (10): 3672–3684. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.1c04419.

- ^ Method of Preparing Organometallic Compounds Using Microchannel Devices, 2009, Francis Joseph Lipiecki, Stephen G. Maroldo, Deodatta Vinayak Shenai-Khatkhate, and Robert A. Ware, US 20090023940

- ^ Purification Process Using Microchannel Devices, 2009, Francis Joseph Lipiecki, Stephen G. Maroldo, Deodatta Vinayak Shenai-Khatkhate, and Robert A. Ware, US 20090020010

- ^ Lai, Sau Man; Martin-Aranda, Rosa; Yeung, King Lun (7 January 2003). "Knoevenagel condensation reaction in a membrane microreactor". Chemical Communications (2): 218–219. doi:10.1039/b209297b. PMID 12585399.

- ^ Costantini, Francesca; Bula, Wojciech P.; Salvio, Riccardo; Huskens, Jurriaan; Gardeniers, Han J. G. E.; Reinhoudt, David N.; Verboom, Willem (11 February 2009). "Nanostructure Based on Polymer Brushes for Efficient Heterogeneous Catalysis in Microreactors". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 131 (5): 1650–1651. Bibcode:2009JAChS.131.1650C. doi:10.1021/Ja807616z. PMID 19143524.

- ^ Uozumi, Yasuhiro; Yamada, Yoichi M. A.; Beppu, Tomohiko; Fukuyama, Naoshi; Ueno, Masaharu; Kitamori, Takehiko (December 2006). "Instantaneous Carbon−Carbon Bond Formation Using a Microchannel Reactor with a Catalytic Membrane". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (50): 15994–15995. Bibcode:2006JAChS.12815994U. doi:10.1021/ja066697r. PMID 17165726.

- ^ Guan, Guoqing; Zapf, Ralf; Kolb, Gunther; Men, Yong; Hessel, Volker; Loewe, Holger; Ye, Jianhui; Zentel, Rudolf (2007). "Low temperature catalytic combustion of propane over Pt-based catalyst with inverse opal microstructure in a microchannel reactor". Chem. Commun. (3): 260–262. doi:10.1039/b609599b. PMID 17299632.

- ^ Bart, Jacob; Kolkman, Ard J.; Oosthoek-de Vries, Anna Jo; Koch, Kaspar; Nieuwland, Pieter J.; Janssen, Hans (J. W. G.); van Bentum, Jan (P. J. M.); Ampt, Kirsten A. M.; Rutjes, Floris P. J. T.; Wijmenga, Sybren S.; Gardeniers, Han (J. G. E.); Kentgens, Arno P. M. (15 April 2009). "A Microfluidic High-Resolution NMR Flow Probe" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 131 (14): 5014–5015. Bibcode:2009JAChS.131.5014B. doi:10.1021/ja900389x. PMID 19320484.

- ^ Carter, Catherine F.; Lange, Heiko; Ley, Steven V.; Baxendale, Ian R.; Wittkamp, Brian; Goode, Jon G.; Gaunt, Nigel L. (19 March 2010). "ReactIR Flow Cell: A New Analytical Tool for Continuous Flow Chemical Processing". Organic Process Research & Development. 14 (2): 393–404. doi:10.1021/op900305v.

- ^ Minnich, Clemens B.; Küpper, Lukas; Liauw, Marcel A.; Greiner, Lasse (August 2007). "Combining reaction calorimetry and ATR-IR spectroscopy for the operando monitoring of ionic liquids synthesis". Catalysis Today. 126 (1–2): 191–195. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2006.12.007.

- ^ Minnich, Clemens B.; Sipeer, Frank; Greiner, Lasse; Liauw, Marcel A. (16 June 2010). "Determination of the Dispersion Characteristics of Miniaturized Coiled Reactors with Fiber-Optic Fourier Transform Mid-infrared Spectroscopy". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 49 (12): 5530–5535. doi:10.1021/ie901094q.