Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chemical synthesis

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

Chemical synthesis (chemical combination) is the artificial execution of chemical reactions to obtain one or more products.[1] This occurs by physical and chemical manipulations, usually involving one or more reactions. In modern laboratory uses, the process is reproducible and reliable.

A chemical synthesis involves one or more compounds (known as reagents or reactants) that will experience a transformation under certain conditions. Various reaction types can be applied to formulate a desired product. This requires mixing the compounds in a reaction vessel, such as a chemical reactor or a simple round-bottom flask. Many reactions require some form of processing ("work-up") or purification procedure to isolate the final product.[1]

The amount produced by chemical synthesis is known as the reaction yield. Typically, yields are expressed as a mass in grams (in a laboratory setting) or as a percentage of the total theoretical quantity that could be produced based on the limiting reagent.[2] A side reaction is an unwanted chemical reaction that can reduce the desired yield. The word synthesis was used first in a chemical context by the chemist Hermann Kolbe.[3]

Strategies

[edit]Chemical synthesis employs various strategies to achieve efficient and precise molecular transformations that are more complex than simply converting a reactant A to a reaction product B directly. These strategies can be grouped into approaches for managing reaction sequences.

Reaction Sequences:

Multistep synthesis involves sequential chemical reactions, each requiring its own work-up to isolate intermediates before proceeding to the next stage.[4] For example, the synthesis of paracetamol typically requires three separate reactions. Divergent synthesis starts with a common intermediate, which branches into multiple final products through distinct reaction pathways. Convergent synthesis synthesis involves the combination of multiple intermediates synthesized independently to create a complex final product. One-pot synthesis involves multiple reactions in the same vessel, allowing sequential transformations without intermediate isolation, reducing material loss, time, and the need for additional purification. Cascade reactions, a specific type of one-pot synthesis, streamline the process further by enabling consecutive transformations within a single reactant, minimizing resource consumption

Catalytic Strategies:

Catalysts play a vital role in chemical synthesis by accelerating reactions and enabling specific transformations. Photoredox catalysis provides enhanced control over reaction conditions by regulating the activation of small molecules and the oxidation state of metal catalysts. Biocatalysis uses enzymes as catalysts to speed up chemical reactions with high specificity under mild conditions.

Reactivity Control:

Chemoselectivity ensures that a specific functional group in a molecule reacts while others remain unaffected. Protecting groups temporarily mask reactive sites to enable selective reactions. Kinetic control prioritizes reaction pathways that form products quickly, often yielding less stable compounds. In contrast, thermodynamic control favors the formation of the most stable products.

Advanced Planning and Techniques:

Retrosynthetic analysis is a strategy used to plan complex syntheses by breaking down the target molecule into simpler precursors. Flow chemistry is a continuous reaction method where reactants are pumped through a reactor, allowing precise control over reaction conditions and scalability. This approach has been employed in the large-scale production of pharmaceuticals such as Tamoxifen.[5]

Organic synthesis

[edit]Organic synthesis is a special type of chemical synthesis dealing with the synthesis of organic compounds. For the total synthesis of a complex product, multiple procedures in sequence may be required to synthesize the product of interest, needing a lot of time. A purely synthetic chemical synthesis begins with basic lab compounds. A semisynthetic process starts with natural products from plants or animals and then modifies them into new compounds.

Inorganic synthesis

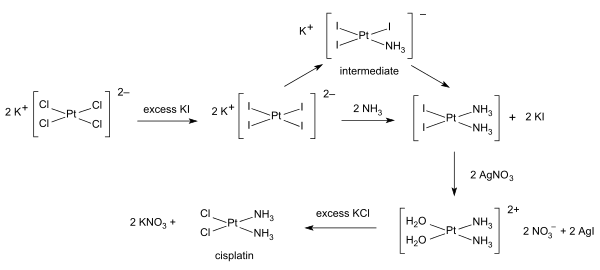

[edit]Inorganic synthesis and organometallic synthesis are used to prepare compounds with significant non-organic content. An illustrative example is the preparation of the anti-cancer drug cisplatin from potassium tetrachloroplatinate.[6]

Green Chemistry

[edit]Chemical synthesis using green chemistry promotes the design of new synthetic methods and apparatus that simplify operations and seeks environmentally benign solvents. Key principles include atom economy, which aims to incorporate all reactant atoms into the final product, and the reduction of waste and inefficiencies in chemical processes. Innovations in green chemistry, contribute to more sustainable and efficient chemical synthesis, reducing the environmental and health impacts of traditional methods.[7]

Applications

[edit]Chemical synthesis plays a crucial role across various industries, enabling the development of materials, medicines, and technologies with significant real-world impacts.

Catalysis: The development of catalysts is vital for numerous industrial processes, including petroleum refining, petrochemical production, and pollution control. Catalysts synthesized through chemical processes enhance the efficiency and sustainability of these operations.[9]

Medicine: Organic synthesis plays a vital role in drug discovery, allowing chemists to develop and optimize new drugs by modifying organic molecules.[9] Additionally, the synthesis of metal complexes for medical imaging and cancer treatments is a key application of chemical synthesis, enabling advanced diagnostic and therapeutic techniques.[10]

Biopharmaceuticals: Chemical synthesis is critical in the production of biopharmaceuticals, including monoclonal antibodies and other biologics. Chemical synthesis enables the creation and modification of organic and biologically sourced compounds used in these treatments. Advanced techniques, such as DNA recombinant technology and cell fusion, rely on chemical synthesis to produce biologics tailored for specific diseases, ensuring they work effectively and target diseases precisely.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Vogel, A.I.; Tatchell, A.R.; Furnis, B.S.; Hannaford, A.J.; Smith, P.W.G. (1996). Vogel's Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-582-46236-3.

- ^ "12.9: Theoretical Yield and Percent Yield". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2016-06-27. Retrieved 2024-12-21.

- ^ Kolbe, H. (1845). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss der gepaarten Verbindungen". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 54 (2): 145–188. doi:10.1002/jlac.18450540202. ISSN 0075-4617. Archived from the original on Jun 30, 2023 – via Zenodo.

- ^ Carey, Francis A.; Sundberg, Richard J. (2013). Advanced Organic Chemistry Part B: Reactions and Synthesis. Springer.

- ^ "Flow chemistry". Vapourtec. Retrieved 2024-12-01.

- ^ Alderden, Rebecca A.; Hall, Matthew D.; Hambley, Trevor W. (1 May 2006). "The Discovery and Development of Cisplatin". J. Chem. Educ. 83 (5): 728. Bibcode:2006JChEd..83..728A. doi:10.1021/ed083p728.

- ^ Li, Chao-Jun; Trost, Barry M (September 9, 2008). "Green chemistry for chemical synthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (35): 13197–13202. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513197L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804348105. PMC 2533168. PMID 18768813.

- ^ Xu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, L. (2011-01-01), Moo-Young, Murray (ed.), "3.18 - Acetic and Propionic Acids", Comprehensive Biotechnology (Second Edition), Burlington: Academic Press, pp. 189–199, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-088504-9.00162-8, ISBN 978-0-08-088504-9, retrieved 2024-12-01

- ^ a b "APPLICATIONS OF ORGANIC CHEMISTRY IN ENGINEERING AND BIOTECHNOLOGY: AN OVERVIEW". Lead & Mentor.

- ^ "Inorganic Synthesis". Socratica.

- ^ "Think : Thermal : Part Two : Uses and Benefits to the biopharmaceutical industry". Thermal Product Solutions. February 10, 2020.

External links

[edit]Chemical synthesis

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Chemical synthesis is the purposeful construction of complex chemical compounds from simpler precursors through controlled chemical reactions, typically in a laboratory or industrial setting, distinguishing it from spontaneous or biosynthetic processes occurring in nature.[1] This artificial process enables the production of molecules not readily available or in sufficient quantities from natural sources, allowing chemists to design and execute transformations to achieve specific molecular architectures.[6] Central to chemical synthesis are several key principles that guide efficient and precise molecular assembly. Atom economy emphasizes maximizing the incorporation of reactant atoms into the desired product to minimize waste, a concept introduced by Barry Trost to evaluate the efficiency of synthetic routes.[7] Stereoselectivity ensures the preferential formation of one stereoisomer over others, crucial for producing molecules with defined three-dimensional structures that influence biological activity.[8] Regioselectivity directs reactions to specific positions within a molecule, favoring one regioisomer when multiple sites are possible, thereby controlling product constitution. Step economy prioritizes routes with the fewest synthetic operations to enhance practicality, reducing time, cost, and resource use.[9] The efficiency of a synthesis is often quantified by percentage yield, calculated as: where the actual yield is the mass of product obtained, and the theoretical yield is the maximum mass predicted from stoichiometry assuming complete conversion.[10] Reagents serve as the primary reactants or additives that undergo transformation to form bonds or introduce functionality, while solvents provide a medium to dissolve reactants, facilitate mixing, and influence reaction rates and selectivity without being consumed. Catalysts accelerate reactions by lowering activation energies, enabling milder conditions and higher selectivity, and are regenerated at the end of the process. Chemical syntheses are classified into types based on starting materials: total synthesis constructs the target entirely from simple, often petrochemical-derived precursors; partial synthesis modifies intermediates toward the final compound; and semi-synthesis alters naturally isolated substances to yield derivatives with enhanced properties. For instance, aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) is produced via semi-synthesis by acetylating salicylic acid, a compound derived from natural sources like willow bark, using acetic anhydride.[11] Retrosynthetic analysis serves as a key planning tool to deconstruct the target molecule into precursors.Historical Overview

The foundations of chemical synthesis were laid in the 18th century through Antoine Lavoisier's experimental work, which established the law of conservation of mass, demonstrating that the total mass of reactants equals the total mass of products in chemical reactions, thereby providing a quantitative basis for synthetic processes.[12] This principle, articulated in Lavoisier's 1789 treatise Traité Élémentaire de Chimie, revolutionized chemistry by shifting focus from qualitative observations to precise measurements essential for reproducible synthesis.[13] The 19th century marked a pivotal shift with the emergence of organic synthesis, beginning with Friedrich Wöhler's 1828 synthesis of urea from ammonium cyanate, an achievement that refuted vitalism—the belief that organic compounds required a vital force—and demonstrated that organic molecules could be created from inorganic materials in the laboratory. This was followed by Hermann Kolbe's 1845 total synthesis of acetic acid from carbon disulfide and other inorganic precursors, which further solidified the synthetic potential of organic chemistry. Entering the 20th century, Emil Fischer's 1890 synthesis of glucose via the Kiliani-Fischer chain elongation method exemplified stereocontrolled carbohydrate synthesis, enabling the structural elucidation and preparation of sugars from simpler aldehydes.[14] Robert Robinson's 1917 synthesis of tropinone, a key alkaloid precursor, introduced retrosynthetic analysis as a strategic planning tool, where the target molecule is deconstructed into simpler precursors to guide forward synthesis.[15] Concurrently, Mikhail Tswett's 1906 development of chromatography using adsorbent columns separated plant pigments like chlorophyll, providing a crucial purification technique that enhanced the isolation of synthetic products.[16] Advancements in the 1930s expanded synthesis to complex macromolecules, such as Wallace Carothers' 1935 polymerization of hexamethylenediamine and adipic acid, which yielded nylon, the first fully synthetic polyamide fiber, demonstrating controlled condensation reactions for industrial-scale polymer synthesis.[17] Post-World War II developments further advanced the field. In the 1940s, the independent discoveries of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy by Felix Bloch and Edward Purcell enabled precise structural confirmation of synthetic compounds through atomic-level analysis of molecular environments.[18] Culminating these efforts, Robert B. Woodward's 1972 total synthesis of vitamin B12 involved over 100 researchers and 195 steps, achieving the construction of its intricate corrin ring system and showcasing the maturity of multistage organic synthesis.[19]Synthesis Strategies

Retrosynthetic Analysis

Retrosynthetic analysis is a systematic method for planning the synthesis of complex molecules by working backward from the target structure to simpler, commercially available precursors through a series of hypothetical retro-reactions, often denoted by disconnection arrows. This disconnective approach, formalized by E.J. Corey in 1967, allows chemists to deconstruct the target molecule step by step, identifying logical synthetic routes that minimize steps and maximize efficiency. At the core of retrosynthetic analysis is the identification of synthons—idealized molecular fragments that represent the reactive species in a disconnection—and their synthetic equivalents, which are actual reagents or starting materials that mimic the synthons' reactivity. Synthons are classified as nucleophilic (donor) or electrophilic (acceptor) based on the polarity of the bond being disconnected, enabling the design of reactions that align with umpolung reactivity when necessary. For instance, a carbon-carbon bond disconnection might generate a carbanion synthon (nucleophilic) and a carbonyl synthon (electrophilic), with equivalents like organometallics and aldehydes used in forward synthesis. Key disconnections in retrosynthetic analysis include functional group interconversions (FGI), which transform one functional group into another to facilitate subsequent bond breaks, such as converting a carboxylic acid to an ester for easier handling. Cycloaddition disconnections reverse pericyclic reactions like the Diels-Alder, breaking two bonds in a six-membered ring to yield a diene and dienophile. Electrophile-nucleophile additions form the basis for many polar disconnections, such as cleaving a C-C bond adjacent to a carbonyl to produce an enolate equivalent (nucleophile) and an alkyl halide (electrophile). A practical example is the retrosynthesis of ibuprofen, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Starting from the target, disconnection at the alpha-carbon of the propionic acid side chain yields an arylacetic acid derivative and a simple electrophile like acetaldehyde equivalent. Further retrosynthesis of the arylacetic acid involves FGI of the carboxylic acid to a nitro group for reduction, followed by disconnection of the isobutyl chain via electrophile-nucleophile addition to a benzene ring precursor. This pathway highlights convergence from readily available materials like isobutylbenzene.[20] Tools for retrosynthetic analysis include the synthon approach pioneered by Corey, which systematically applies disconnections based on established reaction patterns, and transform databases that catalog retro-reactions for computational searching. These databases, derived from Corey's early work on programs like LHASA, store thousands of transforms to generate viable routes efficiently.[21]Forward Synthesis Planning

Forward synthesis planning entails constructing the target molecule through a sequential series of reactions beginning with simple, commercially available starting materials, emphasizing practical execution and iterative refinement of the reaction pathway. This method focuses on applying known transformations in a forward direction to build molecular complexity step by step, often informed by initial route ideation to ensure feasibility. Unlike backward planning approaches, forward planning prioritizes the direct implementation of reactions while anticipating challenges such as side reactions or purification needs at each stage.[22] Key elements in route selection include evaluating the availability of precursors, the scalability of individual reactions, and the overall cost of the process. Availability assesses whether starting materials can be sourced reliably and in sufficient quantities, often favoring commodity chemicals to minimize supply chain risks. Scalability examines how well reactions translate from laboratory to industrial scales, considering factors like heat transfer, mixing efficiency, and reagent handling. Cost analysis incorporates raw material expenses, labor, equipment, and waste management to identify economically viable paths that balance performance with commercial constraints. These criteria guide chemists in choosing routes that align with production goals, such as high-throughput manufacturing for pharmaceuticals.[23] Optimization strategies enhance sequence efficiency by addressing limitations in multi-step processes. Protecting group strategies temporarily mask reactive functional groups to prevent unwanted interactions, allowing selective transformations and reducing side products; common examples include silyl ethers for alcohols or carbamates for amines, which are chosen for their orthogonality and ease of removal. One-pot reactions integrate multiple steps without isolating intermediates, streamlining workflows, minimizing material losses, and improving atom economy by avoiding purification overhead. Convergence in multi-step syntheses involves parallel assembly of molecular fragments that are later combined, shortening the longest linear sequence and amplifying overall efficiency compared to purely linear routes. These techniques collectively reduce step count, boost yields, and lower environmental impact.[24][25][26] A critical metric for assessing multi-step efficiency is the overall yield, defined as the product of the fractional yields from each individual step: where is the yield of the -th step (expressed as a decimal) and is the total number of steps. This multiplicative relationship underscores the sensitivity of long sequences to low-yielding steps; for instance, five steps each at 90% yield result in an overall 59% yield, highlighting the value of optimization.[27] An illustrative example is the forward synthesis of paracetamol (acetaminophen), where p-aminophenol is acetylated using acetic anhydride in aqueous medium to directly form the amide bond at the amine group. This single-step process, often conducted under mild conditions with sulfuric acid catalysis, proceeds in high yield (typically >90%) and exemplifies efficient planning by leveraging a simple, available precursor and avoiding unnecessary steps, making it suitable for large-scale production.[28][29]Organic Synthesis

Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation

Carbon-carbon bond formation constitutes a cornerstone of organic synthesis, enabling the construction of complex carbon frameworks essential for pharmaceuticals, materials, and natural products. These reactions typically involve nucleophilic addition to electrophilic centers like carbonyls or coupling of carbon fragments via transition metals, allowing precise control over molecular architecture. Seminal methods have evolved from early 20th-century organometallic additions to modern catalytic processes, revolutionizing synthetic efficiency. One of the earliest and most versatile C-C bond-forming reactions is the Grignard addition, where an organomagnesium halide (RMgX) acts as a nucleophile toward carbonyl compounds. Developed by Victor Grignard in 1900, this method involves the reaction of RMgX with aldehydes or ketones to yield secondary or tertiary alcohols after acidic workup. The general transformation is represented as: This reaction's broad substrate scope, including alkyl, aryl, and alkenyl Grignard reagents, has made it indispensable, though it requires anhydrous conditions to avoid protonation of the organometallic species.[30] The Wittig olefination provides a stereoselective route to alkenes by forming C-C bonds between carbonyls and phosphonium ylides. Introduced by Georg Wittig in 1954, it proceeds via the reaction of a phosphonium ylide (Ph₃P=CHR) with an aldehyde or ketone, generating an alkene and triphenylphosphine oxide. The process is: Ylides stabilized by conjugating groups yield (E)-alkenes predominantly, while non-stabilized ones favor (Z)-isomers, offering control over double-bond geometry crucial for bioactive molecules. This method's high selectivity and mild conditions have earned it widespread adoption in total synthesis. Transition metal-catalyzed cross-couplings have transformed C-C bond formation by enabling aryl-aryl and vinyl-vinyl linkages under mild conditions. The Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, reported by Norio Miyaura and Akira Suzuki in 1979, couples boronic acids with aryl or vinyl halides using palladium catalysis and a base, producing biaryls in high yields. The reaction is: Its tolerance of aqueous media and functional groups has facilitated industrial applications, including pharmaceutical intermediates, contributing to Suzuki's 2010 Nobel Prize. Similarly, the Heck reaction, pioneered by Richard F. Heck in 1968, involves palladium-catalyzed coupling of aryl or vinyl halides with alkenes to form stilbenes or substituted alkenes, with syn addition and beta-hydride elimination dictating regioselectivity. This migratory insertion mechanism allows for efficient construction of conjugated systems in materials science. The aldol condensation exemplifies base-catalyzed C-C bond formation through enolate addition to carbonyls, followed by dehydration. First reported by Alexander Borodin in 1869 and independently demonstrated by Charles-Adolphe Wurtz in 1872, it converts aldehydes or ketones into α,β-unsaturated carbonyls, as in the self-condensation of acetaldehyde. The key equation is: This reaction's ability to create beta-hydroxy carbonyls or enones under thermodynamic control has been pivotal in polyketide and terpenoid syntheses, with variants like the crossed aldol enabling selective extensions of carbon chains.[31] Asymmetric variants enhance stereocontrol in C-C bond formation, setting the stage for enantiopure products. The Sharpless epoxidation, developed by K. Barry Sharpless in 1980, asymmetrically epoxidizes allylic alcohols using titanium tartrate catalysts, providing epoxy alcohols that serve as precursors for enantioselective C-C extensions via ring-opening or rearrangement. This method's predictable stereochemistry, up to 96% ee, has been transformative in chiral synthesis.[32] Historically, the Reformatsky reaction, invented by Sergei Reformatsky in 1887, introduced zinc enolates for C-C bond formation by reacting α-halo esters with carbonyls to yield β-hydroxy esters. This mild alternative to Grignard reagents avoids strong bases, influencing modern organozinc methodologies. These methods collectively underscore the progression from stoichiometric organometallics to catalytic, stereoselective processes, with post-formation functional group adjustments often refining the resulting scaffolds.Functional Group Transformations

Functional group transformations constitute a cornerstone of organic synthesis, enabling the interconversion of reactive sites within a molecule to facilitate subsequent reactions or achieve desired functionality without altering the core carbon framework. These transformations are pivotal in multistep syntheses, where selective modification of functional groups allows for the precise assembly of complex structures, often serving as preparatory steps following carbon-carbon bond formations. Oxidation and reduction reactions represent fundamental functional group transformations, converting alcohols to carbonyl compounds or vice versa. The Swern oxidation, developed in the late 1970s, provides a mild method for oxidizing primary alcohols to aldehydes and secondary alcohols to ketones using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), oxalyl chloride, and a trialkylamine base such as triethylamine, typically at low temperatures to avoid over-oxidation. This procedure avoids harsh chromium-based reagents and minimizes side reactions, making it widely applicable in sensitive natural product syntheses. In contrast, the Jones oxidation employs chromium trioxide (CrO3) in aqueous sulfuric acid and acetone to fully oxidize primary alcohols directly to carboxylic acids and secondary alcohols to ketones, offering high efficiency for substrates tolerant of acidic conditions but generating toxic chromium waste.[33] Nucleophilic substitution reactions enable the replacement of one functional group with another through attack by a nucleophile, particularly via the SN2 mechanism for primary alkyl halides. A classic example is the conversion of an alkyl halide to an ether using an alkoxide nucleophile, as in the Williamson ether synthesis, where sodium ethoxide reacts with ethyl bromide to yield diethyl ether, proceeding with inversion of configuration and high yield under aprotic conditions. This transformation is valued for its stereospecificity and utility in installing ether linkages in pharmaceuticals and materials. Esterification reactions transform carboxylic acids into esters, a reversible process catalyzed by acid. The Fischer esterification involves heating a carboxylic acid with an alcohol in the presence of a strong acid catalyst like sulfuric acid, yielding the ester and water according to the equilibrium: This method, equilibrium-driven and often shifted by excess alcohol or water removal, is a staple for preparing esters used in fragrances, polymers, and biodiesel, though it requires careful control to avoid side reactions like dehydration.[34] Protecting group strategies are indispensable for temporarily masking functional groups during transformations to prevent unwanted reactivity. For alcohols, the tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS) group is commonly installed using tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (TBDMSCl) and imidazole in dimethylformamide, forming a stable silyl ether that withstands basic conditions and mild acids but can be selectively removed with fluoride ions. This protection is crucial in polyfunctional molecules, enhancing selectivity in total syntheses of alkaloids and antibiotics. Recent advances in functional group transformations have emphasized organocatalysis for asymmetric conversions, reducing reliance on metal catalysts. A landmark example is the proline-catalyzed aldol reaction, where L-proline serves as a chiral organocatalyst to promote the enantioselective addition of ketones to aldehydes, yielding β-hydroxy carbonyl compounds with high enantiomeric excess (up to 99% ee) via an enamine intermediate mechanism. This approach, introduced in 2000, has revolutionized asymmetric synthesis by enabling direct use of unmodified carbonyls and inspiring broader organocatalytic strategies.[35]Inorganic Synthesis

Main Group Element Compounds

The synthesis of compounds involving main group elements from Groups 1, 2, and 13–18 typically emphasizes ionic salt formation, covalent bond constructions, and hydrolysis-condensation processes, yielding structures ranging from simple salts to organoelemental derivatives used in materials and reagents. These routes prioritize high-yield, scalable methods that leverage the elements' electropositive or electronegative nature to facilitate straightforward reactivity, often under mild conditions to control selectivity and avoid side products.[36] For alkali and alkaline earth metals (Groups 1 and 2), salt metathesis reactions serve as a cornerstone for preparing ionic compounds by exchanging anions or cations between precursors, driven by solubility differences or precipitation. A classic example is the reaction of sodium chloride with silver nitrate to produce silver chloride precipitate and sodium nitrate solution, illustrating the double displacement that isolates sparingly soluble main group salts. This method extends to synthesizing alkaline earth derivatives, such as calcium or magnesium complexes, where metathesis with bulky ligands yields homoleptic species under controlled stoichiometry to minimize halide impurities.[37][38] Boron compounds, particularly organoboranes, are accessed via hydroboration, where borane (BH₃) adds across unsaturated hydrocarbons in an anti-Markovnikov, syn fashion, providing versatile intermediates for further transformations. Developed by Herbert C. Brown, this reaction unites boron with alkenes under mild conditions, enabling the formation of trialkylboranes from three equivalents of olefin, as demonstrated in early studies with simple terminal alkenes yielding alkylboranes in high regioselectivity. The process's utility stems from boron's Lewis acidity, facilitating subsequent oxidations or couplings without harsh reagents.[39][39] Silicon-based compounds, essential for silicones and semiconductors, are predominantly synthesized through the direct process, involving the copper-catalyzed reaction of elemental silicon with methyl chloride to produce dimethyldichlorosilane as the primary product. Pioneered by Eugene G. Rochow in the 1940s, this heterogeneous reaction occurs at elevated temperatures (around 300°C), with the equation Si + 2 CH₃Cl → (CH₃)₂SiCl₂ highlighting the selective C-Si bond formation, though byproducts like methyldichlorosilane require distillation for purification. The process's efficiency, yielding over 90% conversion to useful silanes, revolutionized industrial organosilicon production.[40][41] Phosphorus halides, key reagents in organic and inorganic synthesis, are prepared by direct halogenation of white phosphorus. The reaction of tetraphosphorus (P₄) with chlorine gas produces phosphorus trichloride via the balanced equation: This exothermic process, conducted in the liquid phase with PCl₃ as solvent, achieves near-quantitative yields industrially, underscoring phosphorus's reactivity toward halogens to form covalent p-block halides. Additional routes for main group halides and oxides involve halide exchange reactions and sol-gel methods. Halide exchanges allow conversion between chlorine, bromine, or iodine derivatives, leveraging the solubility of byproduct salts for clean separation. For oxides, particularly silica, the sol-gel process hydrolyzes tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) in aqueous ethanol under acidic or basic catalysis, forming a sol that gels into a network via condensation, as in the Stöber method yielding monodisperse nanoparticles. These techniques enable precise control over morphology, with TEOS hydrolysis following Si(OC₂H₅)₄ + 2 H₂O → SiO₂ + 4 C₂H₅OH, producing porous silica gels for applications in catalysis and optics.Transition Metal Complexes

The synthesis of transition metal complexes encompasses a range of strategies tailored to the coordination chemistry of d-block elements, focusing on the formation of stable bonds between metals and ligands in both coordination compounds and organometallics. These methods exploit the variable oxidation states and ligand field effects of transition metals to assemble structures with desired geometries and reactivities. Common approaches include direct ligand substitution, redox-based insertions, and thermal cluster formations, which allow for the preparation of catalytically active species and molecular clusters used in inorganic applications.[42][43] Ligand substitution, or exchange, is a foundational technique for synthesizing coordination complexes, involving the replacement of one or more ligands on the metal center while preserving the overall coordination sphere. This process often proceeds via associative or dissociative mechanisms depending on the metal's electronic configuration and ligand lability. A classic example is the stepwise substitution in cobalt(III) ammine complexes, where hexamminecobalt(III) ions react with ethylenediamine (en) to yield the tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) complex, forming chelate rings that enhance stability: This reaction typically occurs under mild heating in aqueous or alcoholic media, with the bidentate en displacing monodentate NH3 ligands sequentially.[44][42] Such substitutions are widely used to tune the electronic and steric properties of complexes for spectroscopic studies or as precursors to more complex assemblies.[43] In organometallic synthesis, oxidative addition and its reverse, reductive elimination, provide key pathways for incorporating organic fragments into transition metal frameworks, often increasing the metal's oxidation state and coordination number. Oxidative addition involves the insertion of a low-valent metal into a polar bond, such as an alkyl halide, exemplified by palladium(0) species reacting with RX to form a Pd(II) complex: This step is rate-determining in many catalytic cycles and is facilitated by electron-rich metals like Pd(0), proceeding via a concerted three-center transition state. Reductive elimination reverses this by coupling ligands to form new bonds while reducing the metal. These processes are essential for building organometallic intermediates with sigma-bound alkyl or aryl groups.[45][46] A prominent example of ligand substitution in organometallic preparation is the synthesis of Wilkinson's catalyst, chlorotris(triphenylphosphine)rhodium(I), a square-planar Rh(I) complex pivotal for homogeneous catalysis. It is obtained by refluxing rhodium(III) chloride trihydrate with excess triphenylphosphine (PPh3) in ethanol, reducing Rh(III) to Rh(I) while coordinating the phosphine ligands and displacing chloride partially: The excess PPh3 ensures complete substitution, yielding orange crystals after cooling and precipitation; this method achieves high purity suitable for hydrogenation applications. Metal carbonyl clusters, featuring metal-metal bonds and bridging carbonyls, are synthesized through pyrolysis or thermolysis of mononuclear carbonyls, promoting cluster assembly via CO loss and metal aggregation. For iron carbonyls, pyrolysis of iron pentacarbonyl at elevated temperatures (around 120–150°C) generates the triangular triiron dodecacarbonyl cluster: This reaction occurs in the absence of solvent or under inert atmosphere, yielding a golden-yellow solid with a structure containing three Fe atoms bridged by two CO ligands; it exemplifies high-nuclearity cluster formation for studying bonding in polynuclear systems.[47][48] The integration of chiral ligands into transition metal complexes enables the synthesis of enantioselective catalysts, particularly for asymmetric transformations. 2,2'-Bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1'-binaphthyl (BINAP), an atropisomeric diphosphine, is coordinated to rhodium precursors like [Rh(COD)2]BF4 in solvents such as dichloromethane to form air-stable Rh-BINAP complexes used in hydrogenation. These syntheses involve simple ligand exchange, where the bidentate BINAP displaces labile ligands like 1,5-cyclooctadiene, producing complexes with C2-symmetric environments that induce high enantioselectivity in reductions of prochiral alkenes.[49]Specialized Syntheses

Polymer Synthesis

Polymer synthesis involves the formation of long-chain macromolecules from monomeric units, primarily through two mechanisms: chain-growth and step-growth polymerization. These methods enable the production of materials with tailored properties for applications ranging from plastics to fibers. Chain-growth polymerization proceeds via sequential addition of monomers to active chain ends, while step-growth involves reactions between bifunctional monomers leading to condensation products. Both approaches have been foundational since the early 20th century, with advancements allowing precise control over molecular weight and architecture.[50] In chain-growth polymerization, free radical mechanisms are among the most widely used for vinyl monomers. For instance, styrene undergoes free radical polymerization initiated by peroxides, such as benzoyl peroxide, which decomposes to generate radicals that add to the monomer's double bond, propagating the chain until termination. This process yields polystyrene, a versatile thermoplastic, through the reaction: The initiation with peroxy compounds dates back to early 20th-century developments, enabling industrial-scale production of polymers like polystyrene.[50][51] Coordination polymerization represents another chain-growth variant, particularly for olefins. Ethylene is polymerized to high-density polyethylene using Ziegler-Natta catalysts, typically titanium compounds activated by organoaluminum co-catalysts, at moderate pressures and temperatures. The process involves coordination of the monomer to a metal center followed by insertion into a growing chain, as depicted: This discovery in 1953 revolutionized polyolefin production by enabling stereoregular polymers. Step-growth polymerization, often via polycondensation, builds polymers through repeated reactions between functional groups on difunctional monomers, eliminating small molecules like water. A classic example is the synthesis of polyesters from diols and diacids, such as ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid forming polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Similarly, Nylon 6,6 is produced by condensing hexamethylenediamine with adipic acid: This method, pioneered in the 1930s, yields high-strength polyamides essential for textiles and engineering plastics.[17] Controlled chain-growth techniques, such as atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), provide precision in polymer architecture. ATRP uses a transition metal catalyst, like copper(I), to reversibly transfer a halogen atom between dormant chains and active radicals, enabling the synthesis of block copolymers with narrow molecular weight distributions. For example, sequential polymerization of styrene and acrylates via ATRP produces materials with distinct segments for advanced applications. This method, developed in the mid-1990s, has become a cornerstone for functional polymers.[51] Biodegradable polymers like polylactic acid (PLA) are synthesized via ring-opening polymerization of lactide, a cyclic dimer of lactic acid. Using catalysts such as stannous octoate, Sn(Oct)2, the strained ring opens to form linear chains: Developments in the 1980s enabled high-molecular-weight PLA production, supporting its use in sustainable packaging and biomedical devices.[52]Supramolecular Assembly

Supramolecular assembly represents a key paradigm in chemical synthesis, enabling the construction of complex architectures through reversible, non-covalent interactions rather than irreversible covalent bonds. This approach leverages molecular recognition to form dynamic structures, such as host-guest complexes and self-assembled networks, which mimic biological systems and offer tunability for applications in sensing, catalysis, and materials. Pioneered in the late 20th century, supramolecular synthesis emphasizes the programmed organization of molecules into higher-order assemblies, where weak forces dictate specificity and reversibility.[53] The foundational principles of supramolecular assembly rely on non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic effects, which provide the directional and energetic control necessary for selective molecular associations. Hydrogen bonding involves the attraction between a hydrogen atom bonded to an electronegative atom (such as nitrogen or oxygen) and another electronegative atom, offering specificity through geometry and strength typically ranging from 5-30 kJ/mol. π-π stacking arises from the overlap of electron clouds in aromatic systems, stabilizing planar assemblies with energies around 0-50 kJ/mol, while the hydrophobic effect drives the clustering of non-polar moieties in aqueous environments by minimizing unfavorable solvent interactions, with entropic contributions dominating the thermodynamics. These interactions collectively enable the self-organization of molecules into thermodynamically stable complexes, as articulated in the early conceptual framework of supramolecular chemistry.[53][54] A seminal example of host-guest complexation in supramolecular assembly is the use of crown ethers, macrocyclic polyethers that selectively bind alkali metal cations through oxygen lone pairs coordinating the metal center. Charles J. Pedersen first synthesized dibenzo-18-crown-6 in 1967, demonstrating its ability to form stable 1:1 complexes with potassium ions in non-polar solvents, with binding constants on the order of 10^4 M^{-1}, highlighting the role of cavity size matching in selectivity. Similarly, calixarenes, bowl-shaped macrocycles derived from phenol-formaldehyde condensates, serve as versatile hosts for both ionic and neutral guests via their hydrophobic cavities and functionalizable rims. C. David Gutsche's work in 1978 established calix[55]arenes as effective ionophores, capable of encapsulating metal cations or organic molecules through a combination of π-π interactions and van der Waals forces, with association constants varying from 10^2 to 10^6 M^{-1} depending on the guest.[56] Self-assembly extends these principles to larger, more intricate structures, as exemplified by DNA nanotechnology, where nucleotide base pairing drives the formation of branched junctions and lattices. Nadrian C. Seeman proposed in 1982 the use of immobile Holliday junctions—four-stranded DNA motifs with sticky ends—to construct rigid, periodic arrays, enabling the programmable assembly of nanoscale objects with precise geometries. Another prominent self-assembly motif involves rotaxanes, interlocked molecules formed by threading a linear axle through a macrocyclic wheel, stabilized by non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding or electrostatic forces at the stoppers. This threading process relies on template-directed recognition, allowing spontaneous assembly under equilibrium conditions, with yields often exceeding 80% in optimized systems. The stability of such assemblies is quantified by the association constant , defined as which measures the equilibrium preference for the bound state and typically spans 10^2 to 10^8 M^{-1} for effective supramolecular systems.[57] Supramolecular assembly has culminated in the synthesis of molecular machines, such as catenanes—topologically linked ring structures—that exhibit controlled motion. Jean-Pierre Sauvage's 1983 template synthesis using copper(I) coordination to direct the interlocking of two macrocycles marked a breakthrough, producing the first synthetic catenane with high efficiency (up to 70% yield) via non-covalent pre-organization followed by covalent closure. This work, recognized in the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, demonstrated how metal-ligand interactions can template the formation of mechanically interlocked molecules capable of rotary or sliding motions, paving the way for artificial molecular motors. Covalent organic frameworks represent an extension where non-covalent assembly principles guide the initial organization prior to covalent linkage.[58]Green and Sustainable Approaches

Core Principles of Green Chemistry

Green chemistry represents a paradigm shift in chemical synthesis, emphasizing the design of processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances to protect human health and the environment. Central to this approach are the 12 principles formulated by Paul T. Anastas and John C. Warner in their seminal 1998 book, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, which provide a framework for sustainable chemical practices in synthesis by prioritizing prevention over treatment of waste and hazards.[7] These principles guide chemists to integrate environmental considerations into molecular design and process optimization, ensuring that synthetic routes are inherently safer and more efficient from inception. The 12 principles are as follows:- Prevention: It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it has been created.[7]

- Atom Economy: Synthetic methods should be designed to maximize the incorporation of all materials used in the final product.[7]

- Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses: Wherever practicable, synthetic methods should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment.[7]

- Designing Safer Chemicals: Chemical products should be designed to affect their desired function while minimizing toxicity.[7]

- Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used.[7]

- Design for Energy Efficiency: Energy requirements of chemical processes should be recognized for their environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized; synthetic methods should be conducted at ambient temperature and pressure.[7]

- Use of Renewable Feedstocks: A raw material or feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable.[7]

- Reduce Derivatives: Unnecessary derivatization (e.g., using blocking groups or protecting groups) should be minimized or avoided if possible, because such steps require additional reagents and can generate waste.[7]

- Catalysis: Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents.[7]

- Design for Degradation: Chemical products should be designed so that at the end of their function they break down into innocuous degradation products and do not persist in the environment.[7]

- Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention: Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances.[7]

- Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention: Substances and the form of a substance used in a chemical process should be chosen to minimize the potential for chemical accidents, including releases, explosions, and fires.[7]

Eco-Friendly Techniques

Eco-friendly techniques in chemical synthesis emphasize practical methods that minimize environmental impact while maintaining efficiency, guided by principles such as waste prevention and safer solvents. These approaches have gained prominence since the late 20th century, enabling scalable processes with reduced energy consumption and hazardous material use. Solvent-free synthesis represents a key strategy to eliminate volatile organic compounds (VOCs), often accelerated by microwave irradiation to enhance reaction rates. For instance, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition between cyclopentadiene and acetylenic dienophiles proceeds efficiently under microwave-assisted solvent-free conditions, yielding cycloadducts in high purity without traditional solvents, as demonstrated in studies optimizing non-catalyzed reactions.[62] This method reduces waste and simplifies purification, with reaction times shortened from hours to minutes compared to conventional heating.[63] Heterogeneous catalysis facilitates selective transformations using recoverable solid supports, promoting sustainability in processes like hydrogenation. Palladium on carbon (Pd/C) serves as a widely adopted heterogeneous catalyst for alkene hydrogenations, enabling chemoselective reduction of carbon-carbon double bonds in polyfunctional molecules under mild conditions with high recyclability.[64] For example, Pd/C catalyzes the hydrogenation of various alkenes at ppm levels in aqueous media, achieving near-quantitative yields while allowing catalyst reuse over multiple cycles, thus lowering metal leaching and operational costs.[65] Utilizing renewable resources shifts synthesis toward biomass-derived feedstocks, fostering circular economy models. The conversion of sorbitol, obtained from lignocellulosic biomass, to isosorbide via acid-catalyzed dehydration exemplifies this approach, producing a versatile diol for polymers and pharmaceuticals with minimal byproducts.[66] Continuous-flow systems using solid acid catalysts like β-zeolite achieve up to 90% isosorbide yield from aqueous sorbitol solutions at moderate temperatures, avoiding energy-intensive steps and enabling industrial scalability.[67] Alternative reaction media, such as ionic liquids and supercritical CO₂, provide non-volatile, tunable environments developed in the 1990s and 2000s to replace toxic solvents. Ionic liquids, first explored as green solvents in the late 1990s, support diverse reactions like alkylations and extractions due to their low vapor pressure and recyclability, with early applications in biphasic catalysis demonstrating up to 99% recovery rates.[68] Similarly, supercritical CO₂, utilized since the early 2000s for polymerizations and extractions, acts as an inert medium with tunable density, facilitating reactions like hydrogenation without residue formation and enabling easy product separation via pressure release.[69] In green contexts, enzymatic hydrolysis exemplifies mild-condition transformations, represented by the general equation: This avoids harsh acids or bases, reducing energy use and waste, as seen in biomass processing where yields exceed 80% under ambient temperatures.[70]Modern Advances

Computational Methods

Computational methods in chemical synthesis leverage computational chemistry and artificial intelligence to predict reaction outcomes, optimize synthetic routes, and reduce experimental trial-and-error. These approaches enable chemists to model molecular interactions, forecast reaction barriers, and explore vast chemical spaces virtually, accelerating the design of efficient syntheses. By integrating quantum mechanical calculations with machine learning algorithms, computational tools provide insights into mechanistic details and feasibility that guide laboratory efforts. Quantum mechanical methods, particularly density functional theory (DFT), are foundational for predicting reaction barriers and transition states in synthetic pathways. DFT approximates the electronic structure of molecules to compute energies and geometries, allowing evaluation of reaction thermodynamics and kinetics without physical experimentation. The B3LYP hybrid functional, combining Hartree-Fock exchange with Becke's gradient-corrected exchange and Lee-Yang-Parr correlation, is widely used for its balance of accuracy and computational efficiency in modeling organic reactions, often yielding barrier heights within 2-5 kcal/mol of experimental values.[71][72] Software packages like Gaussian facilitate these calculations by implementing DFT and other quantum methods for energy minimization and frequency analysis. In Gaussian, users can perform geometry optimizations and compute activation energies (E_a) to assess reaction viability, often employing basis sets such as 6-31G(d) for routine synthetic predictions. These energies inform the Arrhenius equation, which relates the rate constant (k) to temperature (T) and the pre-exponential factor (A): where R is the gas constant. By deriving E_a from DFT, this equation predicts reaction rates, aiding in the selection of optimal conditions for synthesis steps.[73] Retrosynthesis programs, such as ASKCOS developed in the 2010s, automate the deconstruction of target molecules into precursors using rule-based and data-driven algorithms. ASKCOS employs molecular similarity and reaction templates to generate viable synthetic trees, integrating computational predictions to prioritize routes based on yield and availability of starting materials. Machine learning techniques, including neural networks, enhance reaction prediction by learning patterns from large reaction databases. The IBM RXN for Chemistry platform, launched in 2018, uses a Molecular Transformer model—a sequence-to-sequence neural network—to forecast products from reactants and reagents with over 90% accuracy on benchmark datasets, outperforming traditional rule-based methods in complex organic transformations. This approach treats reactions as "translations" in chemical space, enabling rapid screening of potential syntheses. Recent advances as of 2025 include generative AI models that improve molecular structure sampling and force field development, further speeding up synthesis planning.[74][75][76] A key application is virtual screening for drug synthesis routes, where computational methods evaluate millions of candidates to identify promising pathways. For instance, DFT-based screening combined with machine learning has streamlined the discovery of kinase inhibitors by predicting binding affinities and synthetic accessibility, reducing the number of synthesized compounds by up to 80% while maintaining high hit rates. These tools integrate with retrosynthesis to propose end-to-end routes, from virtual hits to scalable production.[77]Biocatalytic Synthesis

Biocatalytic synthesis utilizes enzymes and whole cells as catalysts to achieve highly selective chemical transformations, integrating biological specificity with synthetic chemistry to produce complex molecules efficiently under mild conditions. This method exploits the regio-, stereo-, and chemoselectivity of biocatalysts, enabling reactions that are challenging or inefficient with traditional chemical approaches. Enzymes operate in aqueous or organic media at ambient temperatures and pressures, often reducing energy consumption and byproduct formation compared to conventional catalysis.[78] Prominent enzyme classes in biocatalytic synthesis include hydrolases and oxidoreductases. Hydrolases, particularly lipases, catalyze esterification reactions by promoting the reversible formation of ester bonds, typically in non-aqueous solvents to favor synthesis over hydrolysis; for instance, Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) is widely used for acylations due to its broad substrate tolerance and stability.[79] Oxidoreductases, such as alcohol dehydrogenases and transaminases, facilitate redox processes, including the reduction of ketones to chiral alcohols or the amination of carbonyls, enabling the production of enantiopure intermediates essential in pharmaceutical synthesis.[78] To adapt natural enzymes for non-native substrates or enhanced performance, directed evolution serves as a key protein engineering strategy, involving random mutagenesis followed by high-throughput screening or selection to iteratively improve catalytic properties. This technique, pioneered by Frances H. Arnold, has revolutionized biocatalysis by generating custom enzymes with novel activities, such as non-natural reaction specificities; Arnold was awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing directed evolution methods that mimic natural selection in the lab.[80] A classic application is the enzymatic kinetic resolution of racemic chiral alcohols via selective acylation with lipases, where the faster-reacting enantiomer forms an ester, allowing facile separation of the unreacted enantiomer; this process achieves high enantiomeric purity (often >99% ee) for secondary alcohols like 1-phenylethanol.[81] The enantioselectivity of such resolutions is evaluated using the E value, a dimensionless parameter independent of conversion, defined by the equation: where is the fractional conversion (0 < C < 1) and is the enantiomeric excess of the product; E > 50 typically indicates practical utility for industrial resolutions. At industrial scales, biocatalytic synthesis has demonstrated viability for large-volume production. Novonesis, a leading enzyme manufacturer, supplies hydrolase-based biocatalysts for detergent formulations, where lipases and proteases hydrolyze lipid and protein stains at low temperatures, improving energy efficiency in laundry processes and capturing over 40% of the global industrial enzyme market as of 2024.[82][83] In pharmaceutical applications, the semi-synthesis of sitagliptin—the active ingredient in the antidiabetic drug Januvia—in the mid-2000s employed an evolved transaminase (an oxidoreductase) developed collaboratively by Codexis and Merck; this biocatalytic step converted a prochiral ketone to the chiral amine intermediate with >99% ee, reducing waste by 85% and eliminating hazardous reagents compared to the prior rhodium-catalyzed process, enabling annual production exceeding 100 tons. Recent developments as of 2025 include computer-aided chemoenzymatic synthesis planning that integrates enzymatic and organic reactions for more efficient hybrid routes.[84][85] Such implementations highlight biocatalysis's alignment with green chemistry principles by prioritizing atom economy and benign conditions.[86]Applications

Pharmaceuticals and Fine Chemicals

Chemical synthesis plays a pivotal role in the development and production of pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals, enabling the creation of complex bioactive molecules essential for therapeutics and high-value specialty products. In drug synthesis, total synthesis approaches allow for the construction of intricate natural products from simple precursors, as exemplified by the 1994 achievement of taxol (paclitaxel), a potent anticancer agent, through a convergent strategy involving over 30 steps and key coupling reactions to assemble the taxane core and side chain. This synthesis not only confirmed taxol's structure but also paved the way for analogs and scalable production, addressing supply limitations from natural sources like Pacific yew bark. Complementing such targeted syntheses, combinatorial chemistry has transformed drug discovery by facilitating the parallel generation of vast compound libraries—often numbering in the millions—for high-throughput screening against biological targets, originating from innovations in solid-phase peptide synthesis in the 1980s and expanding to small molecules in the 1990s.[87][88] Process optimization is crucial for transitioning laboratory-scale syntheses to industrial manufacturing of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), where scale-up challenges include maintaining yield, purity, and safety under larger volumes. Continuous flow chemistry has emerged as a key enabler, allowing precise control of reaction parameters in modular reactors that minimize waste, enhance heat/mass transfer, and support real-time monitoring, as demonstrated in the production of APIs like ibuprofen and aliskiren. This approach contrasts with traditional batch processes by enabling seamless progression from milligrams to kilograms, reducing operator exposure to hazardous intermediates and accelerating time-to-market. Regulatory frameworks ensure quality and safety in these syntheses; the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act mandated proof of drug efficacy through controlled clinical trials and introduced Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards, requiring validated processes, contamination controls, and documentation to prevent adulterated products.[89][90] A landmark example of optimized synthesis is the Boots-Hoechst-Celanese (BHC) process for ibuprofen, an nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, which evolved from the original six-step Boots route patented in the late 1960s into a more efficient three-step variant commercialized in 1992, utilizing catalytic hydrogenation and carbonylation to achieve higher atom economy and reduced environmental impact. This green adaptation minimized waste by recycling byproducts like acetic acid and avoiding stoichiometric reagents, earning recognition as an early model of sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. However, challenges persist in synthesizing chiral drugs, where precise stereoisomer control is vital to avoid adverse effects; the thalidomide tragedy of the late 1950s and early 1960s, involving a racemic mixture that caused thousands of birth defects despite the therapeutic (R)-enantiomer's activity, catalyzed stricter FDA guidelines on enantiomeric purity and chiral resolution techniques like asymmetric catalysis. These lessons underscore the integration of green principles, such as solvent minimization, in pharmaceutical synthesis to align efficiency with safety.[91][92]Materials and Industrial Processes

Chemical synthesis plays a pivotal role in the production of materials at industrial scales, enabling the manufacture of bulk chemicals essential for agriculture, energy, and infrastructure, as well as advanced materials like semiconductors and nanomaterials that drive technological innovation. These processes emphasize efficiency, yield, and cost-effectiveness, often operating under high temperatures, pressures, or specialized conditions to achieve economic viability. While historical methods laid the foundation for high-volume output, modern adaptations incorporate sustainability measures to mitigate environmental impacts without compromising scale. One of the cornerstone processes in bulk chemical synthesis is the Haber-Bosch method for ammonia production, developed in the early 20th century by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. This process fixes atmospheric nitrogen with hydrogen gas via the reversible reaction , catalyzed by iron-based promoters under high pressure (100-300 bar) and temperature (350-500°C) to shift equilibrium toward ammonia formation.[93][94] Introduced commercially in 1913, it revolutionized fertilizer production, supporting global food security by enabling synthetic nitrogen inputs that now account for over 50% of agricultural yields.[93] The process consumes significant energy—approximately 1-2% of global supply—primarily for hydrogen generation from natural gas, highlighting ongoing efforts to integrate renewable hydrogen sources.[94] Petrochemical routes exemplify economic-scale synthesis for commodity materials, with steam cracking of naphtha being the dominant method for ethylene production, a foundational building block for plastics, solvents, and synthetic fibers. In this thermal process, naphtha—a light petroleum fraction—is mixed with steam and heated to 750-900°C in tubular furnaces, where free-radical mechanisms break C-C bonds to yield ethylene (typically 25-35% selectivity) alongside byproducts like propylene and hydrogen.[95][96] Operating at near-atmospheric pressure with short residence times (0.1-0.5 seconds), the reaction's endothermicity demands precise heat management to minimize coke formation and maximize olefin output, with global capacity exceeding 220 million metric tons annually as of 2024.[97] Downstream separation via distillation refines the product stream, underscoring the process's integration into vast petrochemical complexes.[96] For advanced materials, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) enables precise thin-film synthesis in semiconductor manufacturing, depositing materials atom-by-atom onto substrates for electronic devices. In silicon CVD, silane (SiH4) decomposes thermally as at 500-700°C under low pressure, forming polycrystalline or epitaxial silicon layers critical for transistors and solar cells.[98][99] This technique offers conformal coverage and doping control via co-reactants like phosphine, supporting the fabrication of integrated circuits with feature sizes below 5 nm, as evidenced by its role in over 90% of wafer production.[99] Variants like plasma-enhanced CVD lower temperatures for sensitive substrates, enhancing throughput in high-volume fabs.[98] Nanomaterial synthesis via the sol-gel method facilitates the creation of metal oxides with tailored properties for applications like photocatalysis. For titanium dioxide (TiO2), a widely used photocatalyst, the process involves hydrolysis and condensation of precursors such as titanium tetraisopropoxide in alcohol solvents, forming a sol that gels into a network, followed by drying and calcination at 400-600°C to yield anatase-phase nanoparticles (5-50 nm).[100][101] This bottom-up approach controls morphology and surface area (>100 m²/g), enhancing TiO2's UV-induced charge separation for degrading pollutants, with degradation rates up to 90% for model organics under optimized conditions.[100] The method's versatility allows doping or compositing to extend activity into visible light, amplifying its industrial relevance in coatings and environmental remediation.[101] Sustainability in materials synthesis increasingly incorporates circular economy principles, particularly through monomer recycling to close loops in plastic production and reduce reliance on virgin feedstocks. Chemical recycling depolymerizes post-consumer plastics—such as polyesters or polyolefins—back to monomers via pyrolysis, hydrolysis, or catalysis, enabling repolymerization without quality loss and diverting waste from landfills.[102] For instance, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) glycolysis recovers terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol at yields >95%, supporting a closed-loop system that enables the recovery of monomers from post-consumer plastics for repolymerization, with potential to divert significant waste from landfills.[102] This approach minimizes resource depletion, with life-cycle analyses showing 30-70% lower emissions compared to incineration, though challenges like sorting efficiency persist. Industrial polymer methods, such as Ziegler-Natta catalysis, benefit from these recycled monomers to maintain high-throughput production of materials like polyethylene.References

- Synthesis in materials science and engineering is the process of creating a new material by combining different elements or compounds.