Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

District heating

View on Wikipedia

District heating (also known as heat networks) is a system for distributing heat generated in a centralized location through a system of insulated pipes for residential and commercial heating requirements such as space heating and water heating. The heat is often obtained from a cogeneration plant burning fossil fuels or biomass, but heat-only boiler stations, geothermal heating, heat pumps and central solar heating are also used, as well as heat waste from factories and nuclear power electricity generation. District heating plants can provide higher efficiencies and better pollution control than localized boilers. According to some research, district heating with combined heat and power (CHPDH) is the cheapest method of cutting carbon emissions, and has one of the lowest carbon footprints of all fossil generation plants.[1]

District heating is ranked number 27 in Project Drawdown's 100 solutions to global warming.[2][3]

History

[edit]District heating traces its roots to the hot water-heated baths and greenhouses of ancient times, perhaps today most known in the Roman Empire. A hot water distribution system in Chaudes-Aigues in France is generally regarded as the first real district heating system. It used geothermal energy to provide heat for about 30 houses and started operation in the 14th century.[4]

The U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis began steam district heating service in 1853.[citation needed] MIT began coal-fired steam district heating in 1916 when it moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts.[5][6]

Although these and numerous other systems have operated over the centuries, the first commercially successful district heating system was launched in Lockport, New York, in 1877 by American hydraulic engineer Birdsill Holly, considered the founder of modern district heating.

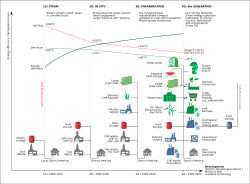

Generations of district heating

[edit]

Generally, all modern district heating systems are demand driven, meaning that the heat supplier reacts to the demand from the consumers and ensures that there is sufficient temperature and water pressure to deliver the demanded heat to the users. The five generations have defining features that sets them apart from the prior generations. The feature of each generation can be used to give an indication of the development status of an existing district heating system.

First generation

[edit]The first generation was a steam-based system fueled by coal and was first introduced in the US in the 1880s and became popular in some European countries, too. It was state of the art until the 1930s. These systems piped very high-temperature steam through concrete ducts, and were therefore not very efficient, reliable, or safe. Nowadays, this generation is technologically outdated. However, some of these systems are still in use, for example in New York or Paris. Other systems originally built have subsequently been upgraded.[7]

Second generation

[edit]The second generation was developed in the 1930s and was built until the 1970s. It burned coal and oil, and the energy was transmitted through pressurized hot water as the heat carrier. The systems usually had supply temperatures above 100 °C, and used water pipes in concrete ducts, mostly assembled on site, and heavy equipment. A main reason for these systems was the primary energy savings, which arose from using combined heat and power plants. While also used in other countries, typical systems of this generation were the Soviet-style district heating systems that were built after WW2 in several countries in Eastern Europe.[7]

Third generation

[edit]In the 1970s the third generation was developed and was subsequently used in most of the following systems all over the world. This generation is also called the "Scandinavian district heating technology", because many of the district heating component manufacturers are based in Scandinavia. The third generation uses prefabricated, pre-insulated pipes, which are directly buried into the ground and operates with lower temperatures, usually below 100 °C. A primary motivation for building these systems was security of supply by improving the energy efficiency after the two oil crises led to disruption of the oil supply. Therefore, those systems usually used coal, biomass and waste as energy sources, in preference to oil. In some systems, geothermal energy and solar energy are also used in the energy mix.[7] For example, Paris has been using geothermal heating from a 55–70 °C source 1–2 km below the surface for domestic heating since the 1970s.[8] Especially in the former Eastern Bloc nuclear energy has been used for district heating[9][10] and new systems keep being installed in China.[11] The source of the heat of nuclear district heating is virtually always waste heat from power reactors, but proposals to build dedicated heating reactors or to use the waste heat from repurposed spent fuel pools[12] have been brought forth.[13][14]

Fourth generation

[edit]Currently,[citation needed] the fourth generation is being developed,[7] with the transition to fourth generation already in process in Denmark.[15] The fourth generation is designed to combat climate change and integrate high shares of variable renewable energy into the district heating by providing high flexibility to the electricity system.[7]

According to the review by Lund et al.[7] those systems have to have the following abilities:

- "Ability to supply low-temperature district heating for space heating and domestic hot water (DHW) to existing buildings, energy-renovated existing buildings and new low-energy buildings."

- "Ability to distribute heat in networks with low grid losses."

- "Ability to recycle heat from low-temperature sources and integrate renewable heat sources such as solar and geothermal heat."

- "Ability to be an integrated part of smart energy systems (i.e. integrated smart electricity, gas, fluid and thermal grids) including being an integrated part of 4th Generation District Cooling systems."

- "Ability to ensure suitable planning, cost and motivation structures in relation to the operation as well as to strategic investments related to the transformation into future sustainable energy systems".

Compared to the previous generations the temperature levels have been reduced to increase the energy efficiency of the system, with supply side temperatures of 70 °C and lower. Potential heat sources are waste heat from industry, CHP plants burning waste, biomass power plants, geothermal and solar thermal energy (central solar heating), large scale heat pumps, waste heat from cooling purposes and data centers and other sustainable energy sources. With those energy sources and large scale thermal energy storage, including seasonal thermal energy storage, fourth generation district heating systems are expected to provide flexibility for balancing wind and solar power generation, for example by using heat pumps to integrate surplus electric power as heat when there is much wind energy or providing electricity from biomass plants when back-up power is needed.[7] Therefore, large scale heat pumps are regarded as a key technology for smart energy systems with high shares of renewable energy up to 100% and advanced fourth generation district heating systems.[16][7][17]

Fifth generation/cold district heating

[edit]

A fifth generation district heating and cooling network (5GDHC),[18] also called cold district heating, distributes heat at near ambient ground temperature: this in principle minimizes heat losses to the ground and reduces the need for extensive insulation. Each building on the network uses a heat pump in its own plant room to extract heat from the ambient circuit when it needs heat, and uses the same heat pump in reverse to reject heat when it needs cooling. In periods of simultaneous cooling and heating demands this allows waste heat from cooling to be used in heat pumps at those buildings which need heating.[19] The overall temperature within the ambient circuit is preferably controlled by heat exchange with an aquifer or another low temperature water source to remain within a temperature range from 10 °C to 25 °C.

While network piping for ambient ground temperature networks is less expensive to install per pipe diameter than in earlier generations, as it does not need the same degree of insulation for the piping circuits, it has to be kept in mind that the lower temperature difference of the pipe network leads to significantly larger pipe diameters than in prior generations. Due to the requirement of each connected building in the fifth generation district heating and cooling systems to have their own heat pump the system can be used both as a heat source or a heat sink for the heat pump, depending on if it is operated in heating or cooling mode. As with prior generations the pipe network is an infrastructure that in principle provides an open access for various low temperature heat sources, such as ambient heat, ambient water from rivers, lakes, sea, or lagoons, and waste heat from industrial or commercial sources.[20]

Based on the above description it is clear that there is a fundamental difference between the 5GDHC and the prior generations of district heating, particularly in the individualization of the heat generation. This critical system has a significant impact when comparing the efficiencies between the different generations, as the individualization of the heat generation moves the comparison from being a simple distribution system efficiency comparison to a supply system efficiency comparison, where both the heat generation efficiency as well as the distribution system efficiency needs to be included.

A modern building with a low-temperature internal heat distribution system can install an efficient heat pump delivering heat output at 45 °C. An older building with a higher-temperature internal distribution system e.g. using radiators will require a high-temperature heat pump to deliver heat output.

A larger example of a fifth generation heating and cooling grid is Mijnwater in Heerlen, the Netherlands.[21][22] In this case the distinguishing feature is a unique access to an abandoned water-filled coal mine within the city boundary that provides a stable heat source for the system.

A fifth generation network ("Balanced Energy Network", BEN) was installed in 2016 at two large buildings of the London South Bank University as a research and development project.[23][24]

Heat sources

[edit]District heating networks exploit various energy sources, sometimes indirectly through multipurpose infrastructure such as combined heat and power plants (CHP, also called co-generation).

Combustion of fossil or renewable fuels

[edit]The most used energy source for district heating is the burning of hydrocarbons. As the supply of renewable fuels is insufficient, the fossil fuels coal and gas are massively used for district heating.[25] This burning of fossil hydrocarbons usually contributes to climate change, as the use of systems to capture and store the CO2 instead of releasing it into the atmosphere is rare.

In the case of a cogeneration plant, the heat output is typically sized to meet half of the peak winter heat load, but over the year will provide 90% of the heat supplied. Much of the heat produced in summer will generally be wasted. The boiler capacity will be able to meet the entire heat demand unaided and can cover for breakdowns in the cogeneration plant. It is not economic to size the cogeneration plant alone to be able to meet the full heat load. In the New York City steam system, that is around 2.5 GW.[26][27] Germany has the largest amount of CHP in Europe.[28]

A simple thermal power station can be 20–35% efficient,[29] whereas a more advanced facility with the ability to recover waste heat can reach total energy efficiency of nearly 80%.[29] Some may approach 100% based on the lower heating value by condensing the flue gas as well.[30]

Nuclear fission

[edit]The heat produced by nuclear chain reactions can be injected into district heating networks. This does not contaminate the district pipes with radioactive elements, as the heat is transferred to the network through heat exchangers.[31] It is not technically necessary for the nuclear reactor to be very close to the district heating network, as heat can be transported over significant distances (exceeding 200 km) with affordable losses, using insulated pipes.[32][clarification needed]

Since nuclear reactors do not significantly contribute to either air pollution or global warming, they can be an advantageous alternative to the combustion of fossil hydrocarbons. However, only a small minority of the nuclear reactors currently in operation around the world are connected to a district heating network. These reactors are in Bulgaria, China, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland and Ukraine.[33][34]

The Sibirskaya Nuclear Power Plant in USSR was the first nuclear CHP plant, supplying district heating to Seversk since 1961 and to a part of Tomsk since 1973, stopped in 2008.[35] The Ågesta Nuclear Power Plant in Sweden was an early example of nuclear cogeneration, providing small quantities of both heat and electricity to a suburb of the country's capital between 1964 and 1974. The Beznau Nuclear Power Plant in Switzerland has been generating electricity since 1969 and supplying district heating since 1984. The Haiyang Nuclear Power Plant in China started operating in 2018 and started supplying small scale heat to the Haiyang city area in 2020. By November 2022, the plant used 345 MW-thermal effect to heat 200,000 homes, replacing 12 coal heating plants.[36]

Recent years have seen renewed interest in small modular reactors (SMRs) and their potential to supply district heating.[37] Speaking on the Energy Impact Center's (EIC) podcast, Titans of Nuclear, principal engineer at GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy Christer Dahlgren noted that district heating could be the impetus for the construction of new nuclear power plants in the future.[38] EIC's own open-source SMR blueprint design, OPEN100, could be incorporated into a district heating system.[39]

Natural underground heat

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2013) |

History

Geothermal district heating was used in Pompeii, and in Chaudes-Aigues since the 14th century.[40]

Denmark

Denmark has one geothermal plant in operation in Thisted since 1984. Two other plants are now closed, located in Copenhagen (2005–2019), and Sønderborg (2013–2018). Both suffered issues with fine sand and blockages[41] [42] [43]

The country's first large-scale plant is being developed near Aarhus, and by the end of 2030, it is expected to be able to cover approximately 20% of the district heating demand in Aarhus.[44]

United States

Direct use geothermal district heating systems, which tap geothermal reservoirs and distribute the hot water to multiple buildings for a variety of uses, are uncommon in the United States, but have existed in America for over a century.

In 1890, the first wells were drilled to access a hot water resource outside of Boise, Idaho. In 1892, after routing the water to homes and businesses in the area via a wooden pipeline, the first geothermal district heating system was created.

As of a 2007 study,[45] there were 22 geothermal district heating systems (GDHS) in the United States. As of 2010, two of those systems have shut down.[46] The table below describes the 20 GDHS currently[when?] operational in America.

| System name | City | State | Startup year |

Number of customers |

Capacity (MWt) |

Annual energy generated (GWh) |

System temperature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °F | °C | |||||||

| Warm Springs Water District | Boise | ID | 1892 | 275 | 3.6 | 8.8 | 175 | 79 |

| Oregon Institute of Technology | Klamath Falls | OR | 1964 | 1 | 6.2 | 13.7 | 192 | 89 |

| Midland | Midland | SD | 1969 | 12 | 0.09 | 0.2 | 152 | 67 |

| College of Southern Idaho | Twin Falls | ID | 1980 | 1 | 6.34 | 14 | 100 | 38 |

| Philip | Philip | SD | 1980 | 7 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 151 | 66 |

| Pagosa Springs | Pagosa Springs | CO | 1982 | 22 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 146 | 63 |

| Idaho Capital Mall | Boise | ID | 1982 | 1 | 3.3 | 18.7 | 150 | 66 |

| Elko | Elko | NV | 1982 | 18 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 176 | 80 |

| Boise City | Boise | ID | 1983 | 58 | 31.2 | 19.4 | 170 | 77 |

| Warren Estates | Reno | NV | 1983 | 60 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 204 | 96 |

| San Bernardino | San Bernardino | CA | 1984 | 77 | 12.8 | 22 | 128 | 53 |

| City of Klamath Falls | Klamath Falls | OR | 1984 | 20 | 4.7 | 10.3 | 210 | 99 |

| Manzanita Estates | Reno | NV | 1986 | 102 | 3.6 | 21.2 | 204 | 95 |

| Elko County School District | Elko | NV | 1986 | 4 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 190 | 88 |

| Gila Hot Springs | Glenwood | NM | 1987 | 15 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 140 | 60 |

| Fort Boise Veteran's Hospital Boise | Boise | ID | 1988 | 1 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 161 | 72 |

| Kanaka Rapids Ranch | Buhl | ID | 1989 | 42 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 98 | 37 |

| In Search Of Truth Community | Canby | CA | 2003 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 185 | 85 |

| Bluffdale | Bluffdale | UT | 2003 | 1 | 1.98 | 4.3 | 175 | 79 |

| Lakeview | Lakeview | OR | 2005 | 1 | 2.44 | 3.8 | 206 | 97 |

Solar heat

[edit]

Use of solar heat for district heating has been increasing in Denmark and Germany[48] in recent years.[49] The systems usually include interseasonal thermal energy storage for a consistent heat output day to day and between summer and winter. Good examples are in Vojens[50] at 50 MW, Dronninglund at 27 MW and Marstal at 13 MW in Denmark.[51][52] These systems have been incrementally expanded to supply 10% to 40% of their villages' annual space heating needs. The solar-thermal panels are ground-mounted in fields.[53] The heat storage is pit storage, borehole cluster and the traditional water tank. In Alberta, Canada the Drake Landing Solar Community has achieved a world record 97% annual solar fraction for heating needs, using solar-thermal panels on the garage roofs and thermal storage in a borehole cluster.[54][55]

Low temperature natural or waste heat

[edit]In Stockholm, the first heat pump was installed in 1977 to deliver district heating sourced from IBM servers. Today the installed capacity is about 660 MW heat, using treated sewage water, sea water, district cooling, data centers and grocery stores as heat sources.[56][57] Another example is the Drammen Fjernvarme District Heating project in Norway which produces 14 MW from water at just 8 °C, industrial heat pumps are demonstrated heat sources for district heating networks. Among the ways that industrial heat pumps can be used are:

- As the primary base load source where water from a low grade source of heat, e.g. a river, fjord, data center, power station outfall, sewage treatment works outfall (all typically between 0 ˚C and 25 ˚C), is boosted up to the network temperature of typically 60 ˚C to 90 ˚C using heat pumps. These devices, although consuming electricity, will transfer a heat output three to six times larger than the amount of electricity consumed. An example of a district system using a heat pump to source heat from raw sewage is in Oslo, Norway that has a heat output of 18 MW(thermal).[58]

- As a means of recovering heat from the cooling loop of a power plant to increase either the level of flue gas heat recovery (as the district heating plant return pipe is now cooled by the heat pump) or by cooling the closed steam loop and artificially lowering the condensing pressure and thereby increasing the electricity generation efficiency.

- As a means of cooling flue gas scrubbing working fluid (typically water) from 60 ˚C post-injection to 20 ˚C pre-injection temperatures. Heat is recovered using a heat pump and can be sold and injected into the network side of the facility at a much higher temperature (e.g. about 80 ˚C).

- Where the network has reached capacity, large individual load users can be decoupled from the hot feed pipe, say 80 ˚C and coupled to the return pipe, at e.g. 40 ˚C. By adding a heat pump locally to this user, the 40 ˚C pipe is cooled further (the heat being delivered into the heat pump evaporator). The output from the heat pump is then a dedicated loop for the user at 40 ˚C to 70 ˚C. Therefore, the overall network capacity has changed as the total temperature difference of the loop has varied from 80 to 40 ˚C to 80 ˚C–x (x being a value lower than 40 ˚C).

Concerns have existed about the use of hydrofluorocarbons as the working fluid (refrigerant) for large heat pumps. Whilst leakage is not usually measured, it is generally reported to be relatively low, such as 1% (compared to 25% for supermarket cooling systems). A 30-megawatt heatpump could therefore leak (annually) around 75 kg of R134a or other working fluid.[59]

However, recent technical advances allow the use of natural heat pump refrigerants that have very low global warming potential (GWP). CO2 refrigerant (R744, GWP=1) or ammonia (R717, GWP=0) also have the benefit, depending on operating conditions, of resulting in higher heat pump efficiency than conventional refrigerants. An example is a 14 MW(thermal) district heating network in Drammen, Norway, which is supplied by seawater-source heatpumps that use R717 refrigerant, and has been operating since 2011. 90 °C water is delivered to the district loop (and returns at 65 °C). Heat is extracted from seawater (from 60-foot (18 m) depth) that is 8 to 9 °C all year round, giving an average coefficient of performance (COP) of about 3.15. In the process the seawater is chilled to 4 °C; however, this resource is not used. In a district system where the chilled water could be used for air conditioning, the effective COP would be considerably higher.[59]

In the future, industrial heat pumps will be further de-carbonised by using, on one side, excess renewable electrical energy (otherwise spilled due to meeting of grid demand) from wind, solar, etc. and, on the other side, by making more of renewable heat sources (lake and ocean heat, geothermal, etc.). Furthermore, higher efficiency can be expected through operation on the high voltage network.[60]

Heat accumulators and storage

[edit]

Increasingly large heat stores are being used with district heating networks to maximise efficiency and financial returns. This allows cogeneration units to be run at times of maximum electrical tariff, the electrical production having much higher rates of return than heat production, whilst storing the excess heat production. It also allows solar heat to be collected in summer and redistributed off season in very large but relatively low-cost in-ground insulated reservoirs or borehole systems. The expected heat loss at the 203,000m³ insulated pond in Vojens is about 8%.[50]

With European countries such as Germany and Denmark moving to very high levels (80% and 100% respectively by 2050) of renewable energy for all energy uses there will be increasing periods of excess production of renewable electrical energy. Heat pumps can take advantage of this surplus of cheap electricity to store heat for later use.[61] Such coupling of the electricity sector with the heating sector (Power-to-X) is regarded as a key factor for energy systems with high shares of renewable energy.[62]

Heat distribution

[edit]

After generation, the heat is distributed to the customer via a network of insulated pipes. District heating systems consist of feed and return lines. Usually the pipes are installed underground but there are also systems with overground pipes. The DH system's start-up and shut downs, as well as fluctuations on heat demand and ambient temperature, induce thermal and mechanical cycling on the pipes due to the thermal expansion. The axial expansion of the pipes is partially counteracted by frictional forces acting between the ground and the casing, with the shear stresses transferred through the PU foam bond. Therefore, the use of pre-insulated pipes has simplified the laying methods, employing cold laying instead of expansion facilities like compensators or U-bends, being so more cost effective.[63] Pre-insulated pipes sandwich assembly composed of a steel heat service pipe, an insulating layer (polyurethane foam) and a polyethylene (PE) casing, which are bonded by the insulating material.[64] While polyurethane has outstanding mechanical and thermal properties, the high toxicity of the diisocyanates required for its manufacturing has caused a restriction on their use.[65] This has triggered research on alternative insulating foam fitting the application,[66] which include polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [67] and polybutylene (PB-1).[68]

Within the system heat storage units may be installed to even out peak load demands.

The common medium used for heat distribution is water or superheated water, but steam is also used. The advantage of steam is that in addition to heating purposes it can be used in industrial processes due to its higher temperature. The disadvantage of steam is a higher heat loss due to the high temperature. Also, the thermal efficiency of cogeneration plants is significantly lower if the cooling medium is high-temperature steam, reducing electric power generation. Heat transfer oils are generally not used for district heating, although they have higher heat capacities than water, as they are expensive and have environmental issues.

At customer level the heat network is usually connected to the central heating system of the dwellings via heat exchangers (heat substations): the working fluids of both networks (generally water or steam) do not mix. However, direct connection is used in the Odense system.

Typical annual loss of thermal energy through distribution is around 10%, as seen in Norway's district heating network.[69]

Heat metering

[edit]The amount of heat provided to customers is often recorded with a heat meter to encourage conservation and maximize the number of customers which can be served, but such meters are expensive. Due to the expense of heat metering, an alternative approach is simply to meter the water – water meters are much cheaper than heat meters, and have the advantage of encouraging consumers to extract as much heat as possible, leading to a very low return temperature, which increases the efficiency of power generation.[citation needed]

Many systems were installed under a socialist economy (such as in the former Eastern Bloc) which lacked heat metering and means to adjust the heat delivery to each apartment.[70][71] This led to great inefficiencies – users had to simply open windows when too hot – wasting energy and reducing the numbers of connectable customers.[72]

Size of systems

[edit]District heating systems can vary in size. Some systems cover entire cities such as Stockholm or Flensburg, using a network of large 1000 mm diameter primary pipes linked to secondary pipes – e.g. 200 mm diameter, which in turn link to tertiary pipes that might be of 25 mm diameter which might connect to 10 to 50 houses.

Some district heating schemes might only be sized to meet the needs of a small village or area of a city in which case only the secondary and tertiary pipes will be needed.

Some schemes may be designed to serve only a limited number of dwellings, of about 20 to 50 houses, in which case only tertiary sized pipes are needed.

Pros and cons

[edit]District heating has various advantages compared to individual heating systems. Usually district heating is more energy efficient, due to simultaneous production of heat and electricity in combined heat and power generation plants. This has the added benefit of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[73] The larger combustion units also have a more advanced flue gas cleaning than single boiler systems. In the case of surplus heat from industries, district heating systems do not use additional fuel because they recover heat which would otherwise be dispersed to the environment.

District heating requires a long-term financial commitment that fits poorly with a focus on short-term returns on investment. Benefits to the community include avoided costs of energy through the use of surplus and wasted heat energy, and reduced investment in individual household or building heating equipment. District heating networks, heat-only boiler stations, and cogeneration plants require high initial capital expenditure and financing. Only if considered as long-term investments will these translate into profitable operations for the owners of district heating systems, or combined heat and power plant operators. District heating is less attractive for areas with low population densities, as the investment per household is considerably higher. Also it is less attractive in areas of many small buildings; e.g. detached houses than in areas with a fewer larger buildings; e.g. blocks of flats, because each connection to a single-family house is quite expensive.

Ownership, monopoly issues and charging structures

[edit]In many cases large combined heat and power district heating schemes are owned by a single entity. This was typically the case in the old Eastern bloc countries. However, for many schemes, the ownership of the cogeneration plant is separate from the heat using part.

Examples are Warsaw which has such split ownership with PGNiG Termika owning the cogeneration unit, the Veolia owning 85% of the heat distribution, the rest of the heat distribution is owned by municipality and workers. Similarly all the large CHP/CH schemes in Denmark are of split ownership.[citation needed]

Sweden provides an alternative example where the heating market is deregulated. In Sweden it is most common that the ownership of the district heating network is not separated from the ownership of the cogeneration plants, the district cooling network or the centralized heat pumps. There are also examples where the competition has spawned parallel networks and interconnected networks where multiple utilities cooperate.[citation needed]

In the United Kingdom there have been complaints that district heating companies have too much of a monopoly and are insufficiently regulated,[74] an issue the industry is aware of, and has taken steps to improve consumer experience through the use of customer charters as set out by the Heat Trust. Some customers are taking legal action against the supplier for Misrepresentation & Unfair Trading, claiming district Heating is not delivering the savings promised by many heat suppliers.[75]

National variation

[edit]Since conditions from city to city differ, every district heating system is unique. In addition, nations have different access to primary energy carriers and so they have a different approach on how to address heating markets within their borders.

Europe

[edit]Since 1954, district heating has been promoted in Europe by Euroheat & Power. They have compiled an analysis of district heating and cooling markets in Europe within their Ecoheatcool project supported by the European Commission. A separate study, entitled Heat Roadmap Europe, has indicated that district heating can reduce the price of energy in the European Union between now and 2050.[76] The legal framework in the member states of the European Union is currently influenced by the EU's CHP Directive.

Cogeneration in Europe

[edit]The EU has actively incorporated cogeneration into its energy policy via the CHP Directive. In September 2008 at a hearing of the European Parliament's Urban Lodgment Intergroup, Energy Commissioner Andris Piebalgs is quoted as saying, "security of supply really starts with energy efficiency."[77] Energy efficiency and cogeneration are recognized in the opening paragraphs of the European Union's Cogeneration Directive 2004/08/EC. This directive intends to support cogeneration and establish a method for calculating cogeneration abilities per country. The development of cogeneration has been very uneven over the years and has been dominated throughout the last decades by national circumstances.

As a whole, the European Union currently generates 11% of its electricity using cogeneration, saving Europe an estimated 35 Mtoe per annum.[78] However, there are large differences between the member states, with energy savings ranging from 2% to 60%. Europe has the three countries with the world's most intensive cogeneration economies: Denmark, the Netherlands and Finland.[79]

Other European countries are also making great efforts to increase their efficiency. Germany reports that over 50% of the country's total electricity demand could be provided through cogeneration. Germany set a target to double its electricity cogeneration from 12.5% of the country's electricity to 25% by 2020 and has passed supporting legislation accordingly in "Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology", (BMWi), Germany, August 2007. The UK is also actively supporting district heating. In the light of UK's goal to achieve an 80% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2050, the government had set a target to source at least 15% of government electricity from CHP by 2010.[80] Other UK measures to encourage CHP growth are financial incentives, grant support, a greater regulatory framework, and government leadership and partnership.

According to the IEA 2008 modelling of cogeneration expansion for the G8 countries, expansion of cogeneration in France, Germany, Italy and the UK alone would effectively double the existing primary fuel savings by 2030. This would increase Europe's savings from today's 155 TWh to 465 TWh in 2030. It would also result in a 16% to 29% increase in each country's total cogenerated electricity by 2030.

Governments are being assisted in their CHP endeavors by organizations like COGEN Europe who serve as an information hub for the most recent updates within Europe's energy policy. COGEN is Europe's umbrella organization representing the interests of the cogeneration industry, users of the technology and promoting its benefits in the EU and the wider Europe. The association is backed by the key players in the industry including gas and electricity companies, ESCOs, equipment suppliers, consultancies, national promotion organisations, financial and other service companies.

A 2016 EU energy strategy suggests increased use of district heating.[81]

Austria

[edit]

The largest district heating system in Austria is in Vienna (Fernwärme Wien) – with many smaller systems distributed over the whole country.

District heating in Vienna is run by Wien Energie. In the business year of 2004/2005 a total of 5,163 GWh was sold, 1,602 GWh to 251,224 private apartments and houses and 3,561 GWh to 5211 major customers. The three large municipal waste incinerators provide 22% of the total in producing 116 GWh electric power and 1,220 GWh heat. Waste heat from municipal power plants and large industrial plants account for 72% of the total. The remaining 6% is produced by peak heating boilers from fossil fuel. A biomass-fired power plant has produced heat since 2006.

In the rest of Austria the newer district heating plants are constructed as biomass plants or as CHP-biomass plants like the biomass district heating of Mödling or the biomass district heating of Baden.

Most of the older fossil-fired district heating systems have a district heating accumulator, so that it is possible to produce the thermal district heating power only at that time where the electric power price is high.

Belgium

[edit]Belgium has district heating in multiple cities. The largest system is in the Flemish city Ghent, the piping network of this power plant is 22 km long. The system dates back to 1958.[83]

Bulgaria

[edit]Bulgaria has district heating in around a dozen towns and cities. The largest system is in the capital Sofia, where there are four power plants (two CHPs and two boiler stations) providing heat to the majority of the city. The system dates back to 1949.[84]

Czech Republic

[edit]The largest district heating system in the Czech Republic is in Prague owned and operated by Pražská teplárenská, serving 265,000 households and selling c. 13 PJ of heat annually. Most of the heat is actually produced as waste heat in 30 km distant thermal power station in Mělník. There are many smaller central heating systems spread around the country[85] including waste heat usage, municipal solid waste incineration and heat plants [de].

Denmark

[edit]In Denmark district heating covers more than 64% of space heating and water heating.[86] In 2007, 80.5% of this heat was produced by combined heat and power plants. Heat recovered from waste incineration accounted for 20.4% of the total Danish district heat production.[87] In 2013, Denmark imported 158,000 ton waste for incineration.[88] Most major cities in Denmark have big district heating networks, including transmission networks operating with up to 125 °C and 25 bar pressure and distribution networks operating with up to 95 °C and between 6 and 10 bar pressure. The largest district heating system in Denmark is in the Copenhagen area operated by CTR I/S and VEKS I/S. In central Copenhagen, the CTR network serves 275,000 households (90–95% of the area's population) through a network of 54 km double district heating distribution pipes providing a peak capacity of 663 MW,[89] some of which is combined with district cooling.[90] The consumer price of heat from CTR is approximately €49 per MWh plus taxes (2009).[91] Several towns have central solar heating with various types of thermal energy storage.

The Danish island of Samsø has three straw-fueled plants producing district heating.[92]

Finland

[edit]In Finland district heating accounts for about 50% of the total heating market,[93] 80% of which is produced by combined heat and power plants. Over 90% of apartment blocks, more than half of all terraced houses, and the bulk of public buildings and business premises are connected to a district heating network. Natural gas is mostly used in the south-east gas pipeline network, imported coal is used in areas close to ports, and peat is used in northern areas where peat is a local resource. Renewables, such as wood chips and other paper industry combustible by-products, are also used, as is the energy recovered by the incineration of municipal solid waste. Industrial units which generate heat as an industrial by-product may sell otherwise waste heat to the network rather than release it into the environment. Excess heat and power from pulp mill recovery boilers is a significant source in mill towns. In some towns waste incineration can contribute as much as 8% of the district heating heat requirement. Availability is 99.98% and disruptions, when they do occur, usually reduce temperatures by only a few degrees.

In Helsinki, an underground datacenter next to the President's palace releases excess heat into neighboring homes,[94] producing enough heat to heat approximately 500 large houses.[95] A quarter of a million households around Espoo are scheduled to receive district heating from datacenters.[96]

Germany

[edit]In Germany district heating has a market share of around 14% in the residential buildings sector. The connected heat load is around 52,729 MW. The heat comes mainly from cogeneration plants (83%). Heat-only boilers supply 16% and 1% is surplus heat from industry. The cogeneration plants use natural gas (42%), coal (39%), lignite (12%) and waste/others (7%) as fuel.[97]

The largest district heating network is located in Berlin whereas the highest diffusion of district heating occurs in Flensburg with around 90% market share. In Munich about 70% of the electricity produced comes from district heating plants.[98]

District heating has rather little legal framework in Germany. There is no law on it as most elements of district heating are regulated in governmental or regional orders. There is no governmental support for district heating networks but a law to support cogeneration plants. As in the European Union the CHP Directive will come effective, this law probably needs some adjustment.

Greece

[edit]Greece has district heating mainly in the province of Western Macedonia, Central Macedonia and the Peloponnese Province. The largest system is the city of Ptolemaida, where there are five power plants (thermal power stations or TPS in particular) providing heat to the majority of the largest towns and cities of the area and some villages. The first small installation took place in Ptolemaida in 1960, offering heating to Proastio village of Eordaea using the TPS of Ptolemaida. Today District heating installations are also available in Kozani, Ptolemaida, Amyntaio, Philotas, Serres and Megalopolis using nearby power plants. In Serres the power plant is a Hi-Efficiency CHP Plant using natural gas, while coal is the primary fuel for all other district heating networks.

Hungary

[edit]According to the 2011 census there were 607,578 dwellings (15.5% of all) in Hungary with district heating, mostly panel flats in urban areas.[99] The largest district heating system located in Budapest, the municipality-owned Főtáv Zrt. ("Metropolitan Teleheating Company") provides heat and piped hot water for 238,000 households and 7,000 companies.[100]

Iceland

[edit]

93% of all housing in Iceland enjoy district heating services – 89.6% from geothermal energy, Iceland is the country with the highest penetration of district heating.[101] There are 117 local district heating systems supplying towns as well as rural areas with hot water – reaching almost all of the population. The average price is around US$0.027 per kWh of hot water.[102]

The Reykjavík Capital Area district heating system serves around 230,000 residents had a maximum thermal power output of 830 MW. In 2018, the average annual heating demand in the Reykjavik area was 473MW.[103] It is the largest district heating system in Iceland and is operated by Veitur. Heat is supplied from the Hellisheiði (200MWth) and Nesjavellir (300MWth) CHP plants, as well as a few lower temperature fields inside Reykjavik. Heating demand has increased steadily as the population has grown, necessitating enlargement of thermal water production in the Hellisheiði CHP plant.[104]

Iceland's second largest district heating system is on the Reykjanes peninsula, with the Svartsengi CHP plant providing heating to 21,000 homes including Keflavik and Grindavik, with a thermal power output of 150 MW.[105]

Ireland

[edit]The Dublin Waste-to-Energy Facility will provide district heating for up to 50,000 homes in Poolbeg and surrounding areas.[106] Some existing residential developments in the North Docklands have been constructed for conversion to district heating – currently using on-site gas boilers – and pipes are in place in the Liffey Service Tunnel to connect these to the incinerator or other waste heat sources in the area.[107]

Tralee, County Kerry has a 1 MW district heating system providing heat to an apartment complex, sheltered housing for the elderly, a library and over 100 individual houses. The system is fuelled by locally produced wood chip.[108]

In Glenstal Abbey, County Limerick there exists a pond-based 150 kW heating system for a school.[109]

A scheme to use waste heat from an Amazon Web Services datacentre in Tallaght is intended to heat 1200 units and municipal buildings[110]

Italy

[edit]

In Italy, district heating is used in some cities (Bergamo, Brescia, Cremona, Bolzano, Verona, Ferrara, Imola, Modena,[111] Reggio Emilia, Terlan, Turin, Parma, Lodi, and now Milan). The district heating of Turin is the biggest of the country and it supplies 550.000 people (62% of the whole city population).

Latvia

[edit]In Latvia, district heating is used in major cities such as Riga, Daugavpils, Liepāja, Jelgava. The first district heating system was constructed in Riga in 1952.[112] Each major city has a local company responsible for the generation, administration, and maintenance of the district heating system.

Netherlands

[edit]District heating is used in Rotterdam,[113][114] Amsterdam, Utrecht,[115] and Almere[116] with more expected as the government has mandated a transition away from natural gas for all homes in the country by 2050.[117] The town of Heerlen has developed a grid using water in disused coalmines as a source and storage for heat and cold. This is a good example of a 5th generation heating and cooling grid[21][22]

North Macedonia

[edit]District heating is only available in Skopje. Balkan Energy Group (BEG) operates three DH production plants, which cover majority of the network, and supply heat to around 60,000 households in Skopje, more than 80 buildings in the educational sector (schools and kindergartens) and more than 1,000 other consumers (mostly commercial).[118] The three BEG production plants use natural gas as a fuel source.[119] There is also one cogeneration plant TE-TO AD Skopje producing heat delivered to the Skopje district heating system. The share of cogeneration in DH production was 47% in 2017. The distribution and supply of district heating is carried out by companies owned by BEG.[118]

Norway

[edit]In Norway district heating only constitutes approximately 2% of energy needs for heating. This is a very low number compared to similar countries. One of the main reasons district heating has a low penetration in Norway is access to cheap hydro-based electricity, and 80% of private electricity consumption goes to heat rooms and water. However, there is district heating in the major cities.

Poland

[edit]

In 2009, 40% of Polish households used district heating, most of them in urban areas.[120] Heat is provided primarily by combined heat and power plants, most of which burn hard coal. The largest district heating system is in Warsaw, owned and operated by Veolia Warszawa, distributing approx. 34 PJ annually.

Romania

[edit]The largest district heating system in Romania is in Bucharest. Owned and operated by RADET, it distributes approximately 24 PJ annually, serving 570 000 households. This corresponds to 68% of Bucharest's total domestic heat requirements (RADET fulfills another 4% through single-building boiler systems, for a total of 72%).

Russia

[edit]

In most Russian cities, district-level combined heat and power plants (ТЭЦ, теплоэлектроцентраль) produce more than 50% of the nation's electricity and simultaneously provide hot water for neighbouring city blocks. They mostly use coal- and gas-powered steam turbines for cogeneration of heat. Now, combined cycle gas turbines designs are beginning to be widely used as well.

Serbia

[edit]In Serbia, district heating is used throughout the main cities, particularly in the capital, Belgrade. The first district heating plant was built in 1961 as a means to provide effective heating to the newly built suburbs of Novi Beograd. Since then, numerous plants have been built to heat the ever-growing city. They use natural gas as fuel, because it has less of an effect on the environment. The district heating system of Belgrade possesses 112 heat sources of 2,454 MW capacity, over 500 km of pipeline, and 4,365 connection stations, providing district heating to 240,000 apartments and 7,500 office/commercial buildings of total floor area exceeding 17,000,000 square meters.[citation needed]

Slovenia

[edit]

The first district heating network in Slovenia and Yugoslavia began to be implemented on November 29, 1959, from the newly built network fed from the Velenje Thermal Power Plant for the needs of the new city center of Velenje. In Slovenia, coverage with district heating systems is 22%, or only 47 out of 210 municipalities have district heating systems. The largest coverage with the district heating system and the lowest price is in Velenje, where all city facilities are connected, so there are no local or individual fireplaces. The prices of MWh of district heat in Slovenia in 2010 ranged between EUR 25 and EUR 93. The largest district heating systems in Slovenia are in Velenje - Šalek Valley and Ljubljana. The total Slovenian installed production and distribution thermal power of all heating systems amounts to 1.7 GW.

Slovakia

[edit]Slovakia's centralised heating system covers more than 54% of the overall demand for heat. In 2015 approximately 1.8 million citizens, 35% of the total population of Slovakia, were served by district heating.[121] The infrastructure was built mainly during the 1960s and 1980s. In recent years large investments were made to increase the share of renewable energy sources and energy efficiency in district heating systems.[122]

The heat production comes mostly from natural gas and biomass sources, and 54% of the heat in district heating is generated through cogeneration.[121] The distribution system consists of 2800 km of pipes. Warm and hot water are the most common heat carriers, but older high-pressure steam transport still accounts for around one-quarter of the primary distribution, which results in more losses in the system.[123]

In terms of the market structure, there were 338 heat suppliers licensed to produce and/or distribute heat in 2016, of which 87% were both producers and distributors. Most are small companies that operate in a single municipality, but some large companies such as Veolia are also present in the market. The state owns and operates large co-generation plants that produce district heat and electricity in six cities (Bratislava, Košice, Žilina, Trnava, Zvolen and Martin). Multiple companies can operate in one city, which is the case in larger cities. A large share of DH is produced by small natural gas heat boilers connected to blocks of buildings. In 2014, nearly 40% of the total DH generation was from natural gas boilers, other than co-generation.[124]

Sweden

[edit]Sweden has a long tradition for using district heating (fjärrvärme) in urban areas. In 2015, about 60% of Sweden's houses (private and commercial) were heated by district heating, according to the Swedish association of district heating.[125] The city of Växjö reduced its CO2 emissions from fossil fuels by 34% from 1993 to 2009.[126] This was to achieved largely by way of biomass fired district heating.[127] Another example is the plant of Enköping, combining the use of short rotation plantations both for fuel as well as for phytoremediation.[128]

In 2024, 46% of the heat generated in Swedish district heating systems was produced with renewable bioenergy sources, as well as 22% in waste-to-energy plants, 7% was provided by heat pumps, 11% by flue-gas condensation and 8% by industrial waste heat recovery. 3% was generated from grid electricity. The remaining was produced by fossil fuels (2%) and peat (0.3%)[129]

Because of the law banning traditional landfills,[130] waste is commonly used as a fuel.

United Kingdom

[edit]

In the United Kingdom, district heating became popular after World War II, but on a restricted scale, to heat the large residential estates that replaced dwellings destroyed by the Blitz. In 2013 there were 1,765 district heating schemes, with 920 based in London alone.[131] In total around 210,000 homes and 1,700 businesses are supplied by heat networks in the UK.[132]

The Pimlico District Heating Undertaking (PDHU) in London first became operational in 1950 and continues to expand to this day. The PDHU once relied on waste heat from the now-disused Battersea Power Station on the south side of the River Thames. It is still in operation; the water is now heated locally by a new energy centre which incorporates 3.1 MWe / 4.0 MWth of gas fired CHP engines and 3 × 8 MW gas-fired boilers.

One of the United Kingdom's largest district heating schemes is EnviroEnergy in Nottingham. The plant, initially built by Boots, is now used to heat 4,600 homes, and a wide variety of business premises, including the Concert Hall, the Nottingham Arena, the Victoria Baths, the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre, the Victoria Centre, and others. The heat source is a waste-to-energy incinerator.

Sheffield's district heating network was established in 1988 and is still expanding today. It saves an equivalent 21,000 plus tonnes of CO2 each year when compared to conventional sources of energy – electricity from the national grid and heat generated by individual boilers. There are currently over 140 buildings connected to the district heating network. These include city landmarks such as the Sheffield City Hall, the Lyceum Theatre, the University of Sheffield, Sheffield Hallam University, hospitals, shops, offices and leisure facilities plus 2,800 homes. More than 44 km of underground pipes deliver energy which is generated at Sheffield Energy Recovery Facility. This converts 225,000 tonnes of waste into energy, producing up to 60 MWe of thermal energy and up to 19 MWe of electrical energy.

The Southampton District Energy Scheme was originally built to use just geothermal energy, but now also uses the heat from a gas-fired CHP generator. It supplies heating and district cooling to many large premises in the city, including the Westquay shopping centre, the De Vere Grand Harbour hotel, the Royal South Hants Hospital, and several housing schemes. In the 1980s Southampton began to use combined heat and power district heating, taking advantage of geothermal heat "trapped" in the area. The geothermal heat provided by the well works in conjunction with the Combined Heat and Power scheme. Geothermal energy provides 15–20%, fuel oil 10%, and natural gas 70% of the total heat input for this scheme and the combined heat and power generators use conventional fuels to make electricity. "Waste heat" from this process is recovered for distribution through the 11 km mains network.[8][133]

Scotland has several district heating systems. The first in the UK was installed at Aviemore, and others followed at Lochgilphead, Fort William and Forfar. Lerwick District Heating Scheme in Shetland is of note because it is one of the few schemes where a completely new system was added to a previously existing small town.

ADE has an online map of district heating installations in the UK.[134] ADE estimates that 54 percent of energy used to produce electricity is being wasted via conventional power production, which relates to £9.5 billion ($US12.5 billion) per year.[135]

North America

[edit]In North America, district heating systems fall into two general categories. Those that are owned by and serve the buildings of a single entity are considered institutional systems. All others fall into the commercial category.

Canada

[edit]District Heating is becoming a growing industry in Canadian cities, with many new systems being built in the last ten years. Some of the major systems in Canada include:

- Calgary: ENMAX currently operates the Calgary Downtown District Energy Centre which provides heating to up to 10,000,000 square feet (930,000 m2) of new and existing residential and commercial buildings. The District Energy Centre began operations in March 2010 providing heat to its first customer, the City of Calgary Municipal building.[136]

- Edmonton: The community of Blatchford, which is currently being developed on the grounds of Edmonton's former City Centre Airport, is launching a District Energy Sharing System (DESS) in phases.[137] A geo-exchange field went online in 2019, and Blatchford's energy utility is in the planning and design phase for a sewage heat exchange system.[138][137]

- Hamilton, ON has a district heating and cooling system in the downtown core, operated by HCE Energy Inc.[139]

- Montreal has a district heating and cooling system in the downtown core.

- Toronto:

- Enwave provides district heating and cooling within the downtown core of Toronto, including deep lake cooling technology, which circulates cold water from Lake Ontario through heat exchangers to provide cooling for many buildings in the city.

- Creative Energy is constructing a combined-heat-and-power district energy system for the Mirvish Village development.

- Surrey: Surrey City Energy owned by the city, provides district heating to the city's City Centre district.[140]

- Vancouver:

- Creative Energy's Beatty Street facility has operated since 1968 and provides a central heating plant for the city's downtown core of Vancouver. In addition to heating 180 buildings, the Central Heat Distribution network also drives a steam clock. Work is currently underway to move the facility from natural gas to electric equipment.

- A large scale district heating system known as the Neighbourhood Energy Utility[141] in the South East False Creek area is in initial operations with natural gas boilers and serves the 2010 Olympic Village. The untreated sewage heat recovery system began operations in January 2010, supplying 70% of annual energy demands, with retrofit work underway to move the facility off its remaining natural gas use.

- Windsor, Ontario has a district heating and cooling system in the downtown core.

- Drake Landing Solar Community, AB, is small in size (52 homes) but notable for having the only central solar heating system in North America.

- London, Ontario and Charlottetown, PEI have district heating co-generation systems owned and operated by Veresen.[142]

- Sudbury, Ontario has a district heating cogeneration system in its downtown core, as well as a standalone cogeneration plant for the Sudbury Regional Hospital. In addition, Naneff Gardens, a new residential subdivision off Donnelly Drive in the city's Garson neighbourhood, features a geothermal district heating system using technology developed by a local company, Renewable Resource Recovery Corporation.[143]

- Ottawa, contains a significant district heating and cooling system serving the large number of federal government buildings in the city. The system loop contains nearly 4,000 m3 (1 million US gal) of chilled or heated water at any time.

- Cornwall, Ontario operates a district heating system which serves a number of city buildings and schools.

- Markham, Ontario: Markham District Energy operates several district heating sites:

- Warden Energy Centre (c. 2000), Clegg Energy Centre and Birchmount Energy Centre serving customers in the Markham Centre area

- Bur Oak Energy Centre (c. 2012) serving customers in the Cornell Centre area

Many Canadian universities operate central campus heating plants.

United States

[edit]As of 2013[update], approximately 2,500 district heating and cooling systems existed in the United States, in one form or another, with the majority providing heat.[144]

- Consolidated Edison of New York (Con Ed) operates the New York City steam system, the largest commercial district heating system in the United States.[145] The system has operated continuously since March 3, 1882, and serves Manhattan Island from the Battery through 96th Street.[146] In addition to providing space- and water-heating, steam from the system is used in numerous restaurants for food preparation, for process heat in laundries and dry cleaners, for steam sterilization, and to power absorption chillers for air conditioning. On July 18, 2007, one person was killed and numerous others injured when a steam pipe exploded on 41st Street at Lexington.[147] On August 19, 1989, three people were killed in an explosion in Gramercy Park.[148]

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has been using district heating for its central business district since the Valley Power Plant commenced operations in 1968.[149] The air quality in the immediate vicinity of the plant, has been measured with significantly reduced ozone levels. The 2012 conversion of the plant, which changed the fuel input from coal to natural gas, is expected to further improve air quality at both the local César Chavez sensor as well as Antarctic sensors[150] The Wisconsin power plants double as breeding grounds for peregrine falcons.[151]

- Denver's district steam system is the oldest continuously operated commercial district heating system in the world. It began service November 5, 1880, and continues to serve 135 customers.[152] The system is partially powered by the Xcel Energy Zuni Cogeneration Station, which was originally built in 1900.[153]

- NRG Energy operates district systems in the cities of San Francisco, Harrisburg, Minneapolis, Omaha, Pittsburgh, and San Diego.[154]

- Seattle Steam Company, a district system operated by Enwave, in Seattle. Enwave also operates district heat system in Chicago, Houston, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, New Orleans, and Portland along with additional Canadian cities.[155]

- Detroit Thermal operates a district system in Detroit that started operation at the Willis Avenue Station in 1903, originally operated by Detroit Edison.[156][157]

- Citizens Energy Group in Indianapolis, Indiana, operates the Perry K. Generating Station, a gas-fired power plant that produces and distributes steam to about 160 downtown Indianapolis customers.[158]

- Lansing Board of Water & Light, a municipal utility system in Lansing, Michigan operates a steam and chilled water system with the steam coming from the natural gas-fired REO Cogeneration Plant and the chilled water coming from the dedicated Roy E. Peffley Chilled Water Plant.[159][160]

- Cleveland Thermal operates a district steam (since 1894) from the Canal Road plant near The Flats and district cooling system (since 1993) from Hamilton Avenue plant on the bluffs east of downtown.

- Veresen operates district heating/co-generation plants in Ripon, California, and San Gabriel, California.[161]

- Veolia Energy, a successor of the 1887 Boston Heating Company,[162] operates a 26-mile (42 km) district system in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, and operates systems in Philadelphia PA, Baltimore MD, Kansas City MO, Tulsa OK, Houston TX and other cities.

- District Energy St. Paul operates the largest hot water district heating system in North America and generates the majority of its energy from an adjacent biomass-fueled combined heat and power plant. In March 2011, a 1 MWh thermal solar array was integrated into the system, consisting of 144 20' x 8' solar panels installed on the roof of a customer building, RiverCentre.

- The California Department of General Services runs a central plant providing district heating to four million square feet in 23 state-owned buildings, including the State Capitol, using high-pressure steam boilers.[163]

- BPU of Jamestown NY operates a second generation water district heating system. It was put into operation in 1984, runs from the BPU electrical plant and provides heat to the business district at Fahrenheit.

Historically, district heating was primarily used in urban areas of the US, but by 1985, it was mainly used in institutions.[164] A handful of smaller municipalities in New England maintained municipal steam into the 21st century, in cities like Holyoke, Massachusetts and Concord, New Hampshire, however the former would end service in 2010 and the latter in 2017, attributing aging infrastructure and capital expenses to their closures.[165][166][167] In 2019, Concord replaced a number of remaining pipes with more efficient ones for a smaller steam system heating only the State House and State Library, mainly due to historic preservation reasons rather than a broader energy plan.[168]

District heating is also used on many college campuses, often in combination with district cooling and electricity generation. Colleges using district heating include the University of Texas at Austin; Rice University;[169] Brigham Young University;[170] Georgetown University;[171] Cornell University,[172] which also employs deep water source cooling using the waters of nearby Cayuga Lake;[173] Purdue University;[174] University of Massachusetts Amherst;[175] University of Maine at Farmington;[176] University of Notre Dame; Michigan State University; Eastern Michigan University;[177] Case Western Reserve University; Iowa State University; University of Delaware;[178] University of Maryland, College Park [citation needed], University of Wisconsin–Madison,[179] University of Georgia,[180] University of Cincinnati,[181] North Carolina State University,[182] University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Duke University, and several campuses of the University of California.[183] MIT installed a cogeneration system in 1995 that provides electricity, heating and cooling to 80% of its campus buildings.[184] The University of New Hampshire has a cogeneration plant run on methane from an adjacent landfill, providing the university with 100% of its heat and power needs without burning oil or natural gas.[185] North Dakota State University (NDSU) in Fargo, North Dakota has used district heating for over a century from their coal-fired heating plant.[186]

Asia

[edit]Japan

[edit]87 district heating enterprises are operating in Japan, serving 148 districts.[187]

Many companies operate district cogeneration facilities that provide steam and/or hot water to many of the office buildings. Also, most operators in the Greater Tokyo serve district cooling.

China

[edit]In southern China (south of the Qinling–Huaihe Line), there are nearly no district heating systems. In northern China, district heating systems are common.[188][189] Most district heating systems are just for heating by burning hard coal instead of CHP. Since air pollution in China has become quite serious, many cities gradually are now using natural gas rather than coal in district heating system. There is also some amount of geothermal heating[190][191] and sea heat pump systems.[192]

In February 2019, China's State Power Investment Corporation (SPIC) signed a cooperation agreement with the Baishan municipal government in Jilin province for the Baishan Nuclear Energy Heating Demonstration Project, which would use a China National Nuclear Corporation DHR-400 (District Heating Reactor 400 MWt).[193][194] Building cost is 1.5 billion yuan ($230 million), taking three years to build.[195]

Turkey

[edit]Geothermal energy in Turkey provides some district heating,[196] and residential district heating and cooling requirements have been mapped.[197]

Market penetration

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (December 2022) |

Penetration of district heating (DH) into the heat market varies by country. Penetration is influenced by different factors, including environmental conditions, availability of heat sources, economics, and economic and legal framework. The European Commission aims to develop sustainable practices through implementation of district heating and cooling technology.[198]

In the year 2000 the percentage of houses supplied by district heat in some European countries was as follows:

| Country | Penetration (2000)[199] |

|---|---|

| Iceland | 95% |

| Denmark | 68% (2024)[86] |

| Estonia | 52% |

| Poland | 52% |

| Sweden | 50% |

| Czech Rep. | 49% |

| Finland | 49% |

| Slovakia | 40% |

| Russia | 35%[200] |

| Germany | 22% (2014)[201] |

| Hungary | 16% |

| Austria | 12.5% |

| France | 7.7% (2017)[202] |

| Netherlands | 3% |

| UK | 2% |

In Iceland the prevailing positive influence on DH is availability of easily captured geothermal heat. In most Eastern European countries, energy planning included development of cogeneration and district heating. Negative influence in the Netherlands and UK can be attributed partially to milder climate, along with competition from natural gas.[citation needed] The tax on domestic gas prices in the UK is a third of that in France and a fifth of that in Germany.

See also

[edit]- District cooling

- Central solar heating

- Geothermal heating

- List of public utilities

- CHP Directive

- New York City steam system

- Public utility

- Thermal energy storage

- Deep water source cooling

- Energy policy of the European Union

- Cost of electricity by source

- Cogeneration

- Alchevsk district heating disaster (2006)

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Carbon footprints of various sources of heat – CHPDH comes out lowest". Claverton Group. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ^ Haas, Arlene (April 12, 2018). "The Overlooked Benefits of District Energy Systems". Burnham Nationwide. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ "District Heating". Drawdown. 2017-02-07. Archived from the original on 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Mazhar, Abdul Rehman; et al. (2018). "a state of art review on district heating systems". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 96: 420–439. Bibcode:2018RSERv..96..420M. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.08.005. S2CID 116827557.

- ^ "Powering Innovation | MIT 2016". mit2016.mit.edu. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ "Energy Efficiency | MIT Sustainability". sustainability.mit.edu. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lund, Henrik; et al. (2014). "4th Generation District Heating (4GDH): Integrating smart thermal grids into future sustainable energy systems". Energy. 68: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2014.02.089.

- ^ a b "Energy from Beneath the Rocks". The Geology of Portsdown Hill. 18 December 2006. Archived from the original on 18 December 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ V.L. Losev; M.V. Sigal; G.E. Soldatov (1989). "Nuclear district heating in CMEA countries" (PDF). IAEA Bulletin. 3. International Atomic Energy Agency: 46–49. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Oliker, Ishai (1 February 2022). "District Heating Supply from Nuclear Power Plants". POWER. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "China starts building long-distance nuclear heating pipeline". World Nuclear News. World Nuclear Association. 17 February 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Palata, Lubos (7 April 2021). "Nuclear heating: A low-cost, greener option?". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Zhang, Yifan; Li, Wenan; Yu, Qian (12 April 2023). "Development Prospect and Application of Nuclear District Heating in China". In Liu, Chengmin (ed.). Springer Proceedings in Physics, vol. 283. Proceedings of the 23rd Pacific Basin Nuclear Conference. Vol. 1. Beijing: China Nuclear Power Engineering Corporation. pp. 8–17. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-1023-6_2. ISBN 978-981-99-1022-9. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Leppänen, Jaakko (10 January 2019). A Review of District Heating Reactor Technology. VTT Research Report No. VTT-R-06895-18 (Report). Espoo: VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Yang, Xiaochen; et al. (2016). "Energy, economy and exergy evaluations of the solutions for supplying domestic hot water from low-temperature district heating in Denmark" (PDF). Energy Conversion and Management. 122: 142–152. Bibcode:2016ECM...122..142Y. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2016.05.057. S2CID 54185636.

- ^ David, Andrei; et al. (2018). "Heat Roadmap Europe: Large-Scale Electric Heat Pumps in District Heating Systems". Energies. 10 (4): 578. doi:10.3390/en10040578.

- ^ Sayegh, M. A.; et al. (2018). "Heat pump placement, connection and operational modes in European district heating". Energy and Buildings. 166: 122–144. Bibcode:2018EneBu.166..122S. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.02.006.

- ^ S.Buffa; et al. (2019). "5th generation district heating and cooling systems: A review of existing cases in Europe". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 104: 504–522. Bibcode:2019RSERv.104..504B. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.12.059.

- ^ "Heat Sharing Network".

- ^ Pellegrini, Marco; Bianchini, Augusto (2018). "The Innovative Concept of Cold District Heating Networks: A Literature Review". Energies. 11: 236pp. doi:10.3390/en11010236. hdl:11585/624860.

- ^ a b Verhoeven, R.; et al. (2014). "Minewater 2.0 Project in Heerlen the Netherlands: Transformation of a Geothermal Mine Water Pilot Project into a Full Scale Hybrid Sustainable Energy Infrastructure for Heating and Cooling". IRES 2013 Conference, Strassbourg. Vol. 46. Energy Procedia, 46 (2014). pp. 58–67. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2014.01.158.

- ^ a b "Heerlen case study and roadmap". Guide to District Heating. HeatNet_NWE EU project. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Balanced Energy Network".

- ^ "About the BEN Project". Archived from the original on 2019-02-18. Retrieved 2019-02-17.

- ^ Chiara Delmastro (November 2021). "District Heating – Analysis - IEA". Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ "Newsroom: Steam". ConEdison. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ Bevelhymer, Carl (2003-11-10). "Steam". Gotham Gazette. Archived from the original on 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ "What is cogeneration?". COGEN Europe. 2015.

- ^ a b "DOE – Fossil Energy: How Turbine Power Plants Work". Fossil.energy.gov. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ^ "Waste-to-Energy CHP Amager Bakke Copenhagen". Archived from the original on 2016-01-10. Retrieved 2015-03-09.

- ^ Patel, Sonal (November 1, 2021). "How an AP1000 Plant Is Changing the Nuclear Power Paradigm Through District Heating, Desalination". Power Magazine. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Safa, Henry (2012). "Heat recovery from nuclear power plants". International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems. 42 (1): 553–559. Bibcode:2012IJEPE..42..553S. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2012.04.052.

- ^ Lipka, Maciej; Rajewski, Adam (2020). "Regress in nuclear district heating. The need for rethinking cogeneration". Progress in Nuclear Energy. 130 103518. Bibcode:2020PNuE..13003518L. doi:10.1016/j.pnucene.2020.103518. S2CID 225166290.

- ^ "District Heating Supply from Nuclear Power Plants". POWER Magazine. 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Северское краеведение". lib.seversk.ru. Retrieved 2025-08-14.

- ^ "Largest nuclear heating project warms China's first carbon-free city". www.districtenergy.org. 21 November 2022.

- ^ "Finnish firm launches SMR district heating project". World Nuclear News. February 24, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ "Christer Dahlgren". Titans of Nuclear. August 30, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Proctor, Darrell (February 25, 2020). "Tech Guru's Plan—Fight Climate Change with Nuclear Power". Power Magazine. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Bloomquist, R. Gordon (2001). Geothermal District Energy System Analysis, Design, and Development (PDF). International Summer School. International Geothermal Association. p. 213(1). Retrieved November 28, 2015.

During Roman times, warm water was circulated through open trenches to provide heating for buildings and baths in Pompeii.

- "Geothermal District Energy System Analysis, Design, and Development". Stanford University (Abstract).

- ^ "Geotermianlæg i drift". Energistyrelsen (in Danish). 2016-04-19. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Madsen, Jacob Lund (2019-05-28). "Hovedstadsområdets fjernvarmeselskaber dropper udvikling af geotermi". Ingeniøren (in Danish).

- ^ "Det blev aldrig en succes: Nu nedlægger Sønderborg Varme geotermianlæg til 187 mio. kroner | jv.dk". jv.dk (in Danish). 2024-01-11.

- ^ "New rules pave the way for large-scale geothermal plant in Denmark". State of Green. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Thorsteinsson, Hildigunnur. "U.S. Geothermal District Heating: Barriers and Enablers" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Lund, John. "The United States of America Country Update 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Pauschinger, Thomas; Schmidt, Thomas (2013). "Solar unterstützte Kraft-Würme-Kopplung mit saisonalem Wärmespeicher". Euroheat & Power. 42 (5): 38–41. ISSN 0949-166X.

- ^ Schmidt T., Mangold D. (2013). Large-scale thermal energy storage – Status quo and perspectives Archived 2016-10-18 at the Wayback Machine. First international SDH Conference, Malmö, SE, 9–10th April 2013. Powerpoint.

- ^ Wittrup, Sanne (23 October 2015). "Fjernvarmeværker går fra naturgas til sol". Ingeniøren. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ a b Wittrup, Sanne (14 June 2015). "Verdens største damvarmelager indviet i Vojens". Ingeniøren. Archived from the original on 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- ^ Holm L. (2012). Long Term Experiences with Solar District Heating in Denmark[permanent dead link]. European Sustainable Energy Week, Brussels. 18–22 June 2012. Powerpoint.

- ^ Current data on Danish solar heat plants Archived 2016-12-23 at the Wayback Machine (click Vojens in South-West Denmark, then "About the plant")

- ^ Dalenbäck, J-O (2012). Large-Scale Solar Heating: State of the Art[permanent dead link]. Presentation at European Sustainable Energy Week, 18–22 June 2012, Brussels, Belgium.

- ^ Wong B., Thornton J. (2013). Integrating Solar & Heat Pumps Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. Renewable Heat Workshop. (Powerpoint)

- ^ Natural Resources Canada, 2012. Canadian Solar Community Sets New World Record for Energy Efficiency and Innovation Archived 2013-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. 5 Oct. 2012.

- ^ Levihn, Fabian (2017). "CHP and heat pumps to balance renewable power production: Lessons from the district heating network in Stockholm". Energy. 137: 670–678. Bibcode:2017Ene...137..670L. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.01.118.

- ^ Bryant, Miranda (28 March 2025). "'The heat you need at a reasonable price': how district heating can speed the switch to clean energy". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ Pedersen, S. & Stene, J. (2006). 18 MW heat pump system in Norway utilises untreated sewage as heat source Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. IEA Heat Pump Centre Newsletter, 24:4, 37–38.

- ^ a b Hoffman, & Pearson, D. 2011. Ammonia heat pumps for district heating in Norway 7 – a case study Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine. Presented at Institute of Refrigeration, 7 April, London.

- ^ "Combined Heat and Power and District Heating report. Joint Research Centre, Petten, under contract to European Commission, DG Energy 2013" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-28. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- ^ DYRELUND Anders, Ramboll, 2010. Heat Plan Denmark 2010

- ^ Lund, Henrik; et al. (2017). "Smart energy and smart energy systems". Energy. 137: 556–565. Bibcode:2017Ene...137..556L. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.05.123.