Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nanometre

View on Wikipedia

| nanometre | |

|---|---|

One nanometric carbon nanotube, photographed with scanning tunneling microscope | |

| General information | |

| Unit system | SI |

| Unit of | length |

| Symbol | nm |

| Conversions | |

| 1 nm in ... | ... is equal to ... |

| SI units | 1×10−9 m 1×103 pm |

| Natural units | 6.1877×1025 ℓP 18.897 a0 |

| imperial/US units | 3.9370×10−8 in |

The nanometre (international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: nm), or nanometer (American spelling), is a unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), equal to one billionth (short scale) or one thousand million (long scale) of a metre (0.000000001 m) and to 1000 picometres. One nanometre can be expressed in scientific notation as 1 × 10−9 m and as 1/1000000000 m.

History

[edit]The nanometre was formerly known as the "millimicrometre" – or, more commonly, the "millimicron" for short – since it is 1/1000 of a micrometre. It was often denoted by the symbol mμ or, more rarely, as μμ (however, μμ should refer to a millionth of a micron).[1][2][3]

Etymology

[edit]The name combines the SI prefix nano- (from the Ancient Greek νάνος, nanos, "dwarf") with the parent unit name metre (from Greek μέτρον, metron, "unit of measurement").

Usage

[edit]Nanotechnologies are based on physical processes which occur on a scale of nanometres (see nanoscopic scale).[1]

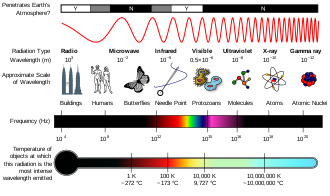

The nanometre is often used to express dimensions on an atomic scale: the diameter of a helium atom, for example, is about 0.06 nm, and that of a ribosome is about 20 nm. The nanometre is also commonly used to specify the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation near the visible part of the spectrum: visible light ranges from around 400 to 700 nm.[4] The ångström, which is equal to 0.1 nm, was formerly used for these purposes.

Since the late 1980s, in usages such as the 32 nm and the 22 nm semiconductor node, it has also been used to describe typical feature sizes in successive generations of the ITRS Roadmap for miniaturized semiconductor device fabrication in the semiconductor industry.

Unicode

[edit]The CJK Compatibility block in Unicode has the symbol U+339A ㎚ SQUARE NM.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Svedberg T, Nichols JB (1923). "Determination of the size and distribution of size of particle by centrifugal methods". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 45 (12): 2910–2917. doi:10.1021/ja01665a016.

- ^ Svedberg T, Rinde H (1924). "The ulta-centrifuge, a new instrument for the determination of size and distribution of size of particle in amicroscopic colloids". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 46 (12): 2677–2693. doi:10.1021/ja01677a011.

- ^ Terzaghi K (1925). Erdbaumechanik auf bodenphysikalischer Grundlage. Vienna: Franz Deuticke. p. 32.

- ^ Hewakuruppu YL, Dombrovsky LA, Chen C, Timchenko V, Jiang X, Baek S, Taylor RA (2013). "Plasmonic " pump – probe " method to study semi-transparent nanofluids". Applied Optics. 52 (24): 6041–6050. Bibcode:2013ApOpt..52.6041H. doi:10.1364/AO.52.006041. PMID 24085009.

External links

[edit]Nanometre

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Scale

Precise Definition

The nanometre (symbol: nm) is a unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), defined as one billionth of a metre, or exactly m.[10] The prefix "nano-", with symbol n, represents a factor of and is one of the twenty-four standard SI prefixes used to denote decimal submultiples of SI units, including the base unit of length, the metre.[10] The metre itself is the SI base unit of length, defined by fixing the numerical value of the speed of light in vacuum to exactly 299 792 458 m/s, where the second is the SI base unit of time defined by caesium hyperfine frequency. As such, the nanometre is a coherent derived SI unit, directly scaled from the metre to express very small lengths. In terms of other units, 1 nm equals exactly 10 ångströms (Å), a non-SI unit historically used in spectroscopy and crystallography and defined as exactly m. The nanometre plays a crucial role in measuring dimensions at the atomic and molecular scales, where typical atomic diameters range from about 0.1 nm to 0.5 nm and molecular structures often span a few nanometres.[11]Comparisons to Other Units

The nanometre (nm) is defined as one billionth of a metre, or .[1] It relates to other length units as follows: (ångströms), where the ångström is a non-SI unit equal to ; (micrometres); and (millimetres).[12][1] These conversions highlight the nanometre's position in the metric system, bridging atomic and macroscopic scales. To grasp its minuteness, consider everyday analogies: the wavelengths of visible light range from approximately 400 nm (violet) to 700 nm (red), meaning a single nanometre is a fraction of the light we perceive.[13] The diameter of a hydrogen atom is about 0.1 nm, so ten such atoms aligned would span one nanometre.[14] In contrast, the average width of a human hair is around 80,000 nm (or 80 μm), equivalent to 800,000 hydrogen atoms side by side.[15] On the broader length scale spectrum, the nanometre occupies a transitional realm: far larger than the Planck length (), the smallest scale in quantum gravity theories, yet vastly smaller than human-scale distances like a metre.[16] For astronomical context, one light-year—the distance light travels in a year—is about , underscoring the nanometre's proximity to atomic dimensions amid cosmic vastness.[17] A relatable proportion illustrates this: one nanometre is to one metre as a marble (about 1 cm in diameter) is to Earth (about 12,742 km in diameter), emphasizing the extreme smallness of nanoscale features relative to everyday objects.Historical Development

Origin of the Prefix

The prefix "nano-" originates from the Greek word nanos (νᾶνος), meaning "dwarf" or "very small," a term historically associated with diminutive figures in mythology and language. This etymological root reflects the prefix's purpose in denoting scales of extreme minuteness, drawing from ancient linguistic traditions to describe something exceedingly tiny.[18][19] In scientific nomenclature, the "nano-" prefix was formally proposed in 1947 during the 14th Conference of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in London, where it was designated to represent a factor of 10^{-9}, or one billionth. This introduction addressed the need for a standardized term to quantify submicroscopic lengths, building on earlier informal usages. Prior to this, smaller scales relied on units like the micron (μ, equivalent to 10^{-6} m), introduced in the late 19th century for microscopic measurements, and the millimicron (mμ, or 10^{-3} μ = 10^{-9} m), which had gained traction in colloid chemistry and optics during the 1920s and 1930s. The millimicron, while practical, was cumbersome as a double prefix, prompting the search for a simpler alternative. Notably, German chemist Richard Adolf Zsigmondy had already employed the term "nanometer" in his 1920s research on gold colloids, using it to specify particle diameters around 1/1,000,000 of a millimeter, though without formal metric status at the time.[18][20][21] By the early 1950s, the "nano-" prefix began appearing in physics and chemistry literature, particularly in fields like spectroscopy and electron microscopy, where precise measurement of atomic and molecular dimensions was essential. For instance, it facilitated descriptions of wavelengths in ultraviolet spectroscopy and particle sizes in nuclear physics experiments, gradually supplanting the millimicron notation for clarity and consistency. This early adoption in scientific publications laid the groundwork for its broader integration into the metric system by 1960, though details of that standardization belong to later developments.[20]Standardization and Adoption

The nanometre (nm), defined as one billionth of a metre (10^{-9} m), was formally incorporated into the International System of Units (SI) through Resolution 12 of the 11th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) in 1960, which established the SI framework and included the "nano-" prefix among the standard decimal multipliers for all base units, including the metre.[22] This adoption built on earlier metric prefix conventions but integrated them into the newly named Système International d'Unités, ensuring consistency in scientific measurement across disciplines.[1] Usage of the nanometre expanded significantly in the post-1980s era, driven by breakthroughs in scanning probe microscopy (SPM), such as the invention of the scanning tunneling microscope (STM) in 1981, which enabled atomic-scale imaging and routinely employed nanometre units for resolution and feature sizing.[23] By the 1990s, the nanotechnology boom—marked by discoveries like carbon nanotubes in 1991—propelled the nanometre from niche applications in solid-state physics to a universal standard for describing structures and phenomena at the 1–100 nm scale, reflecting its growing indispensability in interdisciplinary research.[24] International standards bodies have played a pivotal role in standardizing the nanometre's symbol and conventions. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), through ISO 80000-1:2022, defines the nanometre as 10^{-9} m and endorses "nm" as its symbol for use in quantities and units. Similarly, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) affirms "nm" in its SI guidelines, promoting uniform application in metrology and engineering.[1] The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), in its Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (Green Book, 2007), reinforces "nm" for wavelength and length measurements, ensuring alignment with SI practices.Applications

In Nanotechnology and Materials Science

Nanotechnology is defined as the understanding and control of matter at the nanoscale, typically involving dimensions between 1 and 100 nanometres, to create materials, devices, and systems with novel properties and functions.[25] This scale enables engineers to manipulate atoms and molecules to design structures that exhibit behaviors distinct from their bulk counterparts.[26] At the nanometre scale, quantum effects become prominent, altering the electrical, optical, and mechanical properties of materials due to quantum confinement, where electrons are restricted in space, leading to discrete energy levels rather than continuous bands.[27] Additionally, the high surface-to-volume ratio of nanomaterials dramatically increases reactivity, as a greater proportion of atoms reside on the surface, enhancing interactions with surrounding environments.[28] For instance, carbon nanotubes, which have diameters typically ranging from 1 to 10 nanometres, demonstrate exceptional tensile strength and electrical conductivity owing to these nanoscale phenomena.[29] In materials science, nanoparticles serve as highly efficient catalysts because their small size maximizes active surface sites for chemical reactions, such as in hydrogenation processes where gold nanoparticles accelerate reaction rates under mild conditions.[30] Nanocomposites, incorporating nanofillers like carbon nanotubes into polymer matrices, significantly enhance mechanical strength and toughness.[31] Key tools for probing and fabricating at this scale include atomic force microscopy (AFM), which achieves lateral resolutions down to approximately 1 nanometre, allowing visualization and manipulation of surface features at the atomic level.[32] The conceptual foundations of nanotechnology trace back to Richard Feynman's 1959 lecture "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom," which envisioned manipulating matter atom by atom, inspiring subsequent developments in nanometre-scale engineering.[33]In Biology and Medicine

In biology, the nanometre scale is essential for understanding the dimensions of key biomolecular structures. The DNA double helix, for instance, has a diameter of approximately 2 nm, allowing it to fit within the confines of cellular nuclei while enabling intricate packaging mechanisms.[34] Proteins, the building blocks of cellular function, typically range in size from 1 to 10 nm, influencing their folding, interactions, and roles in enzymatic processes.[35] Cell membranes, composed of lipid bilayers, are about 5 nm thick, providing a selective barrier that regulates molecular transport and signaling.[36] Viruses and antibodies further exemplify the relevance of nanometre-scale measurements in immunology and virology. Most viruses measure between 20 and 300 nm in diameter, with their size directly affecting infectivity, immune evasion, and vaccine design strategies.[37] Antibodies, such as immunoglobulin G (IgG), have dimensions on the order of 10 nm, enabling precise binding to antigens on pathogen surfaces for neutralization.[38] Advanced imaging techniques leverage the nanometre to visualize these structures at unprecedented detail. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) preserves biological samples in vitreous ice and achieves resolutions down to the nanometre scale, revealing conformational changes in proteins and macromolecular complexes.[39] Super-resolution microscopy techniques, including stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) and stimulated emission depletion (STED), surpass the diffraction limit of conventional light microscopy—approximately 200 nm—allowing localization of fluorescently labeled biomolecules with 20-50 nm precision.[40] In medicine, nanometre-scale engineering enhances therapeutic interventions, particularly through targeted delivery systems. Liposomes, spherical vesicles with diameters around 100 nm, encapsulate drugs for site-specific release, improving bioavailability and reducing systemic toxicity in treatments for cancer and infections.[41] Conceptual frameworks for nanobots—hypothetical devices operating at 10-100 nm—envision autonomous navigation through bloodstreams to perform tasks like precise surgery or real-time diagnostics, though current prototypes focus on passive targeting rather than full mobility.[42]In Physics and Electronics

In fundamental physics, the nanometre scale is crucial for describing phenomena involving light and atomic structures. Ultraviolet (UV) light, which spans wavelengths from approximately 100 nm to 400 nm, plays a key role in spectroscopy and photochemistry, where precise measurements at this scale enable the study of molecular interactions and material properties.[43] Similarly, atomic orbitals, which define the spatial distribution of electrons around nuclei, have characteristic sizes on the order of 0.1 nm; for instance, the Bohr radius for the hydrogen atom's 1s orbital is 0.0529 nm, setting the fundamental length scale for quantum mechanical descriptions of atoms.[44] In electronics, the nanometre unit underpins the scaling described by Moore's Law, which has driven exponential increases in transistor density by reducing feature sizes, enabling the integration of billions of transistors on chips. As of 2025, advanced semiconductor process nodes, such as TSMC's 2 nm technology entering mass production, feature transistor gate lengths around 12 nm, allowing for enhanced performance and power efficiency in devices like microprocessors and GPUs while approaching physical limits imposed by quantum effects.[45] At these scales, quantum phenomena become prominent; for example, quantum tunneling in nanometre-scale junctions permits electrons to pass through insulating barriers as thin as 1-3 nm, which is essential for operations in flash memory but poses challenges like leakage currents in ultra-scaled transistors.[46] Ballistic transport, where electrons travel through nanowires without scattering over lengths up to several hundred nanometres, further exemplifies how nm-scale engineering minimizes resistance and enables high-speed signal propagation in nanoscale interconnects.[47] Nanometre precision is integral to fabricating key electronic devices. Quantum dots, semiconductor nanocrystals typically 2-10 nm in diameter, exhibit size-dependent optical and electrical properties due to quantum confinement, making them ideal for applications in photodetectors and single-photon sources.[48] In light-emitting diodes (LEDs), active layers and quantum wells are engineered with thicknesses on the order of 1-100 nm to optimize carrier recombination and emission efficiency, as seen in high-brightness GaN-based LEDs where precise nm-scale layering enhances output power and color purity.[49]Notation and Representation

Symbols and Usage Conventions

The standard symbol for the nanometre in the International System of Units (SI) is "nm", consisting of the prefix symbol "n" for nano (10^{-9}) combined with the symbol "m" for metre, with no space between the prefix and the base unit symbol.[10] Unit symbols like "nm" are always written in roman (upright) typeface, regardless of the surrounding text style, and are not italicized.[50] According to SI conventions established by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the numerical value precedes the unit symbol with a single space separating them, as in "5 nm" for five nanometres; no space is used before the symbol in the compound form.[51] Unit symbols do not change form for plural quantities, so "nm" is used whether singular or plural, while the spelled-out name follows standard English pluralization as "nanometre" or "nanometres" in international contexts, preferring the British spelling "metre" to align with the original French "mètre".[51] In textual writing, "nm" is preferred for brevity, whereas in mathematical equations, the explicit form m is recommended to denote the nanometre precisely.[52] A common error in scientific notation arises from potential ambiguity with the millinewton-metre (a unit of torque, symbol mN·m), which may be ambiguously written as "mNm" without separators; to distinguish it clearly from "nm", the SI recommends inserting a raised dot (·) or a space in compound units, such as "m N·m" or "m N m".[51] This practice ensures unambiguous communication in technical documents, as outlined in the BIPM SI Brochure.[53]Digital and Typographic Representation

In digital systems, the nanometre symbol "nm" is encoded using the standard Latin lowercase letters "n" (Unicode U+006E LATIN SMALL LETTER N) and "m" (Unicode U+006D LATIN SMALL LETTER M), as there is no dedicated Unicode character for the unit in the primary ranges. A compatibility character, U+339A ㎚ SQUARE NM, exists in the CJK Compatibility block for legacy East Asian typography approximating "nm", but it is not recommended for general use in SI-compliant documents.[54] Typographically, "nm" is rendered in upright (roman) font to distinguish it from variables, per SI conventions, with a thin space or non-breaking space separating the preceding numeral to prevent line breaks, as in "5 nm".[51] In some typefaces, the adjacent rounded forms of "n" and "m" can lead to suboptimal default kerning, requiring manual adjustment in design software for balanced spacing in technical contexts.[55] For digital typesetting tools, LaTeX supports "nm" via the siunitx package, using commands like\si{\nano\metre} to produce properly formatted output with correct spacing and font.[56] In HTML and CSS, the unit is simply written as text, with non-breaking spaces ( ) or CSS properties like white-space: nowrap applied to the number-unit pair for layout control, and superscript notation (e.g., via <sup>2</sup>) for powers like nm².

Historically, before widespread Unicode adoption in the 1990s, the nanometre was represented in ASCII-based systems simply as the sequence "nm", leveraging the basic Latin alphabet available since ASCII standardization in 1963, without special encoding.References

- https://en.wikichip.org/wiki/technology_node