Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nonsense

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

Nonsense is a form of communication, via speech, writing, or any other formal logic system, that lacks any coherent meaning. In ordinary usage, nonsense is sometimes synonymous with absurdity or the ridiculous. Many poets, novelists and songwriters have used nonsense in their works, often creating entire works using it for reasons ranging from pure comic amusement or satire, to illustrating a point about language or reasoning. In the philosophy of language and philosophy of science, nonsense is distinguished from sense or meaningfulness, and attempts have been made to come up with a coherent and consistent method of distinguishing sense from nonsense. It is also an important field of study in cryptography regarding separating a signal from noise.

Literary

[edit]The phrase "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously" was coined by Noam Chomsky as an example of nonsense. The individual words make sense and are arranged according to proper grammatical rules, yet the result is nonsense. The inspiration for this attempt at creating verbal nonsense came from[citation needed] the idea of contradiction and seemingly irrelevant and/or incompatible characteristics, which conspire to make the phrase meaningless, but are open to interpretation. The phrase "the square root of Tuesday" operates on the latter[which?] principle. This principle is behind the inscrutability of the kōan "What is the sound of one hand clapping?", where one hand would presumably be insufficient for clapping.[citation needed]

Verse

[edit]Jabberwocky, a poem (of nonsense verse) found in Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll (1871), is a nonsense poem written in the English language. The word jabberwocky is also occasionally used as a synonym of nonsense.[1]

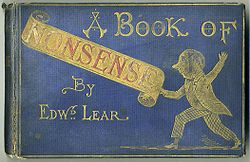

Nonsense verse is the verse form of literary nonsense, a genre that can manifest in many other ways. Its best-known exponent is Edward Lear, author of The Owl and the Pussycat and hundreds of limericks.

Nonsense verse is part of a long line of tradition predating Lear: the nursery rhyme Hey Diddle Diddle could also be termed a nonsense verse. There are also some works which appear to be nonsense verse, but actually are not, such as the popular 1940s song Mairzy Doats.

Lewis Carroll, seeking a nonsense riddle, once posed the question How is a raven like a writing desk?. Someone answered him, Because Poe wrote on both. However, there are other possible answers (e.g. both have inky quills).

Examples

[edit]The first verse of Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll;

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

The first four lines of On the Ning Nang Nong by Spike Milligan;[2]

On the Ning Nang Nong

Where the cows go Bong!

and the monkeys all say BOO!

There's a Nong Nang Ning

The first verse of Spirk Troll-Derisive by James Whitcomb Riley;[3]

The Crankadox leaned o'er the edge of the moon,

And wistfully gazed on the sea

Where the Gryxabodill madly whistled a tune

To the air of "Ti-fol-de-ding-dee."

The first four lines of The Mayor of Scuttleton by Mary Mapes Dodge;[3]

The Mayor of Scuttleton burned his nose

Trying to warm his copper toes;

He lost his money and spoiled his will

By signing his name with an icicle quill;

Oh Freddled Gruntbuggly by Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz; a creation of Douglas Adams

Oh freddled gruntbuggly,

Thy micturations are to me

As plurdled gabbleblotchits on a lurgid bee.

Groop I implore thee, my foonting turlingdromes,

And hooptiously drangle me with crinkly bindlewurdles,

Or I will rend thee in the gobberwarts

With my blurglecruncheon, see if I don't!

Philosophy of language and of science

[edit]In the philosophy of language and the philosophy of science, nonsense refers to a lack of sense or meaning. Different technical definitions of meaning delineate sense from nonsense.

Logical positivism

[edit]Wittgenstein

[edit]In Ludwig Wittgenstein's writings, the word "nonsense" carries a special technical meaning which differs significantly from the normal use of the word. In this sense, "nonsense" does not refer to meaningless gibberish, but rather to the lack of sense in the context of sense and reference. In this context, logical tautologies, and purely mathematical propositions may be regarded as "nonsense". For example, "1+1=2" is a nonsensical proposition.[4] Wittgenstein wrote in Tractatus Logico Philosophicus that some of the propositions contained in his own book should be regarded as nonsense.[5] Used in this way, "nonsense" does not necessarily carry negative connotations.

Disguised Epistemic Nonsense

[edit]In Ludwig Wittgenstein’s later work, Philosophical Investigations (PI §464), he says that “My aim is: to teach you to pass from a piece of disguised nonsense to something that is patent nonsense.” In his remarks On Certainty (OC), he considers G. E. Moore’s “Proof of an External World” as an example of disguised epistemic nonsense. Moore’s “proof” is essentially an attempt to assert the truth of the sentence ‘Here is one hand’ as a paradigm case of genuine knowledge. He does this during a lecture before The British Academy where the existence of his hand is so obvious as to appear indubitable. If Moore does indeed know that he has a hand, then philosophical skepticism (formerly called idealism) must be false. (cf. Schönbaumsfeld (2020).

Wittgenstein however shows that Moore’s attempt fails because his proof tries to solve a pseudo-problem that is patently nonsensical. Moore mistakenly assumes that syntactically correct sentences are meaningful regardless of how one uses them. In Wittgenstein’s view, linguistic meaning for the most part is the way sentences are used in various contexts to accomplish certain goals (PI §43). J. L. Austin likewise notes that "It is, of course, not really correct that a sentence ever is a statement: rather, it is used in making a statement, and the statement itself is a 'logical construction' out of the makings of statements" (Austin 1962, p1, note1). Disguised epistemic nonsense therefore is the misuse of ordinary declarative sentences in philosophical contexts where they seem meaningful but produce little or nothing of significance (cf. Contextualism). Moore’s unintentional misuse of ‘Here is one hand’ thus fails to state anything that his audience could possibly understand in the context of his lecture.

According to Wittgenstein, such propositional sentences instead express fundamental beliefs that function as non-cognitive “hinges”. Such hinges establish the rules by which the language-game of doubt and certainty is played. Wittgenstein points out that “If I want the door to turn the hinges must stay put” (OC §341-343).[6] In a 1968 article titled “Pretence”, Robert Caldwell states that: “A general doubt is simply a groundless one, for it fails to respect the conceptual structure of the practice in which doubt is sometimes legitimate” (Caldwell 1968, p49). "If you are not certain of any fact," Wittgenstein notes, "you cannot be certain of the meaning of your words either" (OC §114). Truth-functionally speaking, Moore’s attempted assertion and the skeptic’s denial are epistemically useless. "Neither the question nor the assertion makes sense" (OC §10). In other words, both philosophical realism and its negation, philosophical skepticism, are nonsense (OC §37&58). Both bogus theories violate the rules of the epistemic game that make genuine doubt and certainty meaningful. Caldwell concludes that: “The concepts of certainty and doubt apply to our judgments only when the sense of what we judge is firmly established” (Caldwell, p57).

The broader implication is that classical philosophical “problems” may be little more than complicated semantic illusions that are empirically unsolvable (cf. Schönbaumsfeld 2016). They arise when semantically correct sentences are misused in epistemic contexts thus creating the illusion of meaning. With some mental effort however, they can be dissolved in such a way that a rational person can justifiably ignore them. According to Wittgenstein, "It is not our aim to refine or complete the system of rules for the use of our words in unheard-of ways. For the clarity that we are aiming at is indeed complete clarity. But this simply means that the philosophical problems should completely disappear" (PI §133). The net effect is to expose a “A whole cloud of philosophy condensed into a drop of grammar” (PI p222).

In contrast to the above Wittgensteinian approach to nonsense, Cornman, Lehrer and Pappas argue in their textbook, Philosophical Problems and Arguments: An Introduction (PP&A) that philosophical skepticism is perfectly meaningful in the semantic sense. It is only in the epistemic sense that it seems nonsensical. For example, the sentence ‘Worms integrate the moon by C# when moralizing to rescind apples’ is neither true nor false and therefore is semantic nonsense. Epistemic nonsense, however, is perfectly grammatical and semantical. It just appears to be preposterously false. When the skeptic boldly asserts the sentence [x]: ‘We know nothing whatsoever’ then:

“It is not that the sentence asserts nothing; on the contrary, it is because the sentence asserts something [that seems] patently false…. The sentence uttered is perfectly meaningful; what is nonsensical and meaningless is the fact that the person [a skeptic] has uttered it. To put the matter another way, we can make sense of the sentence [x]; we know what it asserts. But we cannot make sense of the man uttering it; we do not understand why he would utter it. Thus, when we use terms like ‘nonsense’ and ‘meaningless’ in the epistemic sense, the correct use of them requires only that what is uttered seem absurdly false. Of course, to seem preposterously false, the sentence must assert something, and thus be either true or false.” (PP&A, 60).

Keith Lehrer makes a similar argument in part VI of his monograph, “Why Not Scepticism?” (WNS 1971). A Wittgensteinian, however, might respond that Lehrer and Moore make the same mistake. Both assume that it is the sentence [x] that is doing the “asserting”, not just the philosopher’s misuse of it in the wrong context. Both Moore’s attempted “assertion” and the skeptic’s “denial” of ‘Here is one hand’ in the context of the British Academy are preposterous. Therefore, both claims are epistemic nonsense disguised in meaningful syntax. “[T]he mistake here” according to Caldwell, “lies in thinking that [epistemic] criteria provide us with certainty when they actually provide sense” (Caldwell p53). No one, including philosophers, has special dispensation from committing this semantic fallacy.

“The real discovery,” according to Wittgenstein, “is the one that makes me capable of stopping doing philosophy when I want to.—The one that gives philosophy peace, so that it is no longer tormented by questions which bring itself in question…. There is not a philosophical method, though there are indeed methods, like different therapies” (PI §133). He goes on to say that “The philosopher's treatment of a question is like the treatment of an illness” (PI §255).

Leonardo Vittorio Arena

[edit]Starting from Wittgenstein, but through an original perspective, the Italian philosopher Leonardo Vittorio Arena, in his book Nonsense as the meaning, highlights this positive meaning of nonsense to undermine every philosophical conception which does not take note of the absolute lack of meaning of the world and life. Nonsense implies the destruction of all views or opinions, on the wake of the Indian Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna. In the name of nonsense, it is finally refused the conception of duality and the Aristotelian formal logic.

Cryptography

[edit]The problem of distinguishing sense from nonsense is important in cryptography and other intelligence fields. For example, they need to distinguish signal from noise. Cryptanalysts have devised algorithms to determine whether a given text is in fact nonsense or not. These algorithms typically analyze the presence of repetitions and redundancy in a text; in meaningful texts, certain frequently used words recur, for example, the, is and and in a text in the English language. A random scattering of letters, punctuation marks and spaces do not exhibit these regularities. Zipf's law attempts to state this analysis mathematically. By contrast, cryptographers typically seek to make their cipher texts resemble random distributions, to avoid telltale repetitions and patterns which may give an opening for cryptanalysis.[citation needed]

It is harder for cryptographers to deal with the presence or absence of meaning in a text in which the level of redundancy and repetition is higher than found in natural languages (for example, in the mysterious text of the Voynich manuscript).[citation needed]

Teaching machines to talk nonsense

[edit]Scientists have attempted to teach machines to produce nonsense. The Markov chain technique is one method which has been used to generate texts by algorithm and randomizing techniques that seem meaningful. Another method is sometimes called the Mad Libs method: it involves creating templates for various sentence structures and filling in the blanks with noun phrases or verb phrases; these phrase-generation procedures can be looped to add recursion, giving the output the appearance of greater complexity and sophistication. Racter was a computer program which generated nonsense texts by this method; however, Racter's book, The Policeman’s Beard is Half Constructed, proved to have been the product of heavy human editing of the program's output.

See also

[edit]

|

|

Notes

[edit]- ^ "the definition of Jabberwocky". Dictionary.com.

- ^ "Top poetry is complete nonsense". BBC News. 10 October 1998.

- ^ a b A Nonsense Anthology. 1 November 2005 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Schroeder, Severin (2006). Wittgenstein: the way out of the fly-bottle. Polity. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7456-2615-4.

- ^ Biletzki, Anat and Anat Matar, "Ludwig Wittgenstein", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2008 Edition) "The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy"

6. A new branch of philosophy called “hinge epistemology” has sprouted from Wittgenstein’s remarks On Certainty. See Duncan Pritchard, Crispin Wright, Daniele Moyal-Sharrock, et al. Whether Wittgenstein would have agreed with their interpretations of his work is debatable.

References

[edit]- Kahn, David, The Codebreakers (Scribner, 1996) ISBN 0-684-83130-9

- Austin, J. L. (1962). "How to Do Things with Words", The William James Lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Caldwell, Robert L., “Pretence” (Jan. 1968), Mind, New Series, Vol. 77, No. 305.

- James Cornman, Keith Lehrer & George Pappas (PP&A 1992). Philosophical Problems and Arguments: An Introduction – 4th ed. Hackett Publishing Co., Inc., Indianapolis.

- Lehrer, Keith (WNS 1971). “Why Not Scepticism?” part VI, Philosophical Forum, vol. II, 289-290.

- Schönbaumsfeld, Genia (2016). The Illusion of Doubt. Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-878394-7

- Schönbaumsfeld, Genia (2020). "G E Moore's Attempt to Refute Scepticism and Wittgenstein's Critique" video lecture. University of South Hampton. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SINqcUocOAU.

- Cohen, Roni and Idels, Ofer. (2024) "Israeli Nonsense: humor, globalization and vegetables during the early nineties," Humor.