Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

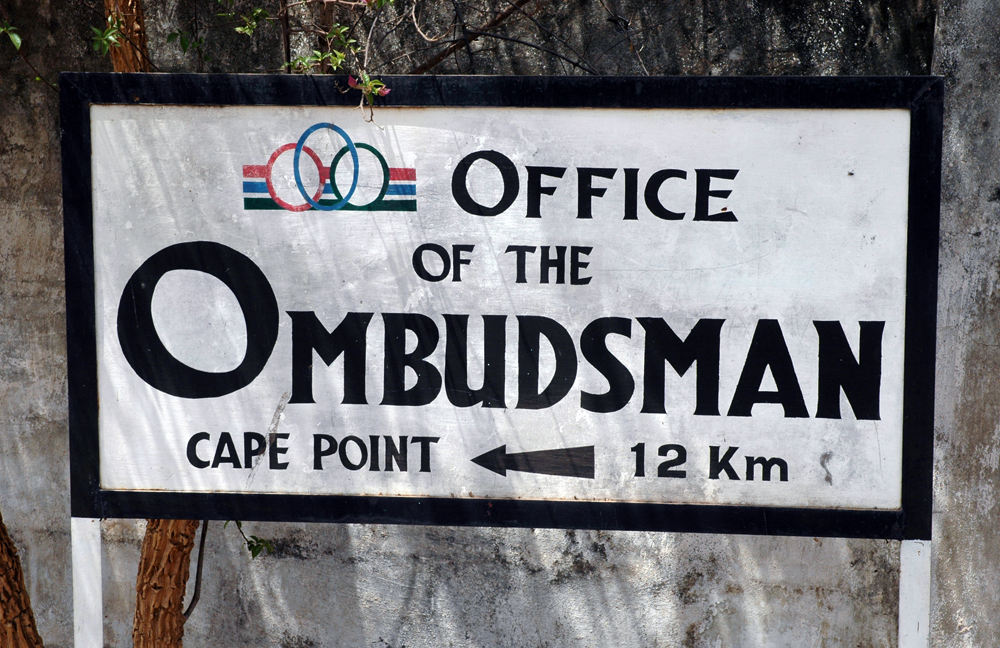

Ombudsman

View on Wikipedia

An ombudsman (/ˈɒmbʊdzmən/ OM-buudz-mən, also US: /-bədz-, -bʌdz-/ -bədz-, -budz-[1][2][3]) is a government official who investigates and tries to resolve complaints, usually through recommendations (binding or not) or mediation. They are usually appointed by the government or by parliament (often with a significant degree of independence).

Ombudsmen also aim to identify systemic issues leading to poor service or breaches of people's rights. At the national level, most ombudsmen have a wide mandate to deal with the entire public sector, and sometimes also elements of the private sector (for example, contracted service providers). In some cases, there is a more restricted mandate to a certain sector of society. More recent developments have included the creation of specialized children's ombudsmen.

In some countries, an inspector general, citizen advocate or other official may have duties similar to those of a national ombudsman and may also be appointed by a legislature. Below the national level, an ombudsman may be appointed by a state, local, or municipal government. Private ombudsmen may be appointed by, or even work for, a corporation such as a utility supplier, newspaper, NGO, or professional regulatory body.

In some jurisdictions, an ombudsman charged with handling concerns about national government is more formally referred to as the "parliamentary commissioner" (e.g. the United Kingdom Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration, and the Western Australian state Ombudsman). In many countries where the ombudsman's responsibility includes protecting human rights, the ombudsman is recognized as the national human rights institution. The post of ombudsman had by the end of the 20th century been instituted by most governments and by some intergovernmental organizations such as the European Union. As of 2005, including national and sub-national levels, a total of 129 offices of ombudsman have been established around the world.[4]

Origins and etymology

[edit]A prototype of an ombudsman may have flourished in China during the Qin dynasty (221 BC), and later in Korea during the Joseon dynasty.[5] The position of secret royal inspector, or amhaeng-eosa (암행어사, 暗行御史) was unique to the Joseon dynasty, where an undercover official directly appointed by the king was sent to local provinces to monitor government officials and look after the populace while travelling incognito. The Roman tribune had some similar roles, with the power to veto acts that infringed upon the Plebeians. Another precursor to the ombudsman was the Diwān al-Maẓālim (دِيوَانُ الْمَظَالِمِ) which appears to go back to the second caliph, Umar (634–644), and the concept of Qaḍī al-Quḍāt (قَاضِي الْقُضَاةِ).[6] They were also attested in Siam, India, the Liao dynasty, Japan, and China.[7]

An indigenous Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish term, ombudsman, ombodsmann, ombudsmann or ombudsmand is etymologically rooted in the Old Norse word umboðsmaðr, essentially meaning 'representative' (with the word umbud/ombod/ombud meaning 'proxy', 'attorney'; that is, someone who is authorized to act for someone else, a meaning it still has in the Scandinavian languages). In the Danish Law of Jutland from 1241, the term is umbozman and concretely means a royal civil servant in a hundred. From 1552, it is also used in other Nordic languages such as the Icelandic and Faroese umboðsmaður, the Norwegian ombudsmann/ombodsmann, and the Swedish ombudsman (pronounced [ˈɔ̂mːbʉːdsˌman] ⓘ). The general meaning was and is approximately 'a man representing (someone)' (i.e., a representative) or 'a man with a commission (from someone)' (a commissioner). The Swedish-speaking minority in Finland uses the Swedish terminology. The various forms of the suffix -mand, -maður, et cetera, are just the forms the common Germanic word represented by the English word man have in the various languages. Thus, the modern plural form ombudsmen of the English borrowed word ombudsman is likely.

Use of the term in its modern sense began in Sweden with the Swedish Parliamentary Ombudsman instituted by the Instrument of Government of 1809, to safeguard the rights of citizens by establishing a supervisory agency independent of the executive branch. The predecessor of the Swedish Parliamentary Ombudsman was the Office of Supreme Ombudsman (Högste Ombudsmannen), which was established by the Swedish King, Charles XII, in 1713. Charles XII was in exile in Turkey and needed a representative in Sweden to ensure that judges and civil servants acted in accordance with the laws and with their duties. If they did not do so, the Supreme Ombudsman had the right to prosecute them for negligence. In 1719 the Swedish Office of Supreme Ombudsman became the Chancellor of Justice.[8] The Parliamentary Ombudsman was established in 1809 by the Swedish Riksdag, as a parallel institution to the still-present Chancellor of Justice, reflecting the concept of separation of powers as developed by Montesquieu.[8]

The Parliamentary Ombudsman is the institution that the Scandinavian countries subsequently developed into its contemporary form, and which subsequently has been adopted in many other parts of the world. The word ombudsman and its specific meaning have since been adopted in various languages, such as Dutch. The German language uses Ombudsmann, Ombudsfrau and Ombudsleute. Notable exceptions are French, Italian, Spanish, and Finnish, which use translations instead. Modern variations of this term include ombud, ombuds, ombudsperson, or ombudswoman, and the conventional English plural is ombudsmen. In Nigeria, the ombudsman is known as the Public Complaints Commission or the ombudsman.[9]

In politics

[edit]In general, an ombudsman is a state official appointed to provide a check on government activity in the interests of the citizen and to oversee the investigation of complaints of improper government activity against the citizen. If the ombudsman finds a complaint to be substantiated, the problem may get rectified, or an ombudsman report is published making recommendations for change. Further redress depends on the laws of the country concerned, but this typically involves financial compensation. Ombudsmen in most countries do not have the power to initiate legal proceedings or prosecution on the grounds of a complaint. This role is sometimes referred to as a "tribunician" role, and has been traditionally fulfilled by elected representatives – the term refers to the ancient Roman "tribunes of the plebeians" (tribuni plebis), whose role was to intercede in the political process on behalf of common citizens.

The significant advantage of an ombudsman is that they examine complaints from outside the offending state institution, thus avoiding the conflicts of interest inherent in self-policing. However, the ombudsman system relies heavily on the selection of an appropriate individual for the office, and on the cooperation of at least some effective official from within the apparatus of the state. However, sociologist Jürgen Beyer has criticised the institution, stating: "Ombudsmen are relics of absolutism, designed to iron out the worst excesses of administrative arbitrariness while keeping the power structures intact."[10]

In organizations

[edit]Many private companies, universities, non-profit organisations, and government agencies also have an ombudsman (or an ombuds office) to serve internal employees, managers and/or other constituencies. These ombudsman roles are structured to function independently, by reporting to the CEO or board of directors, and, according to the International Ombudsman Association (IOA) Standards of Practice, they do not have any other role in the organisation. Organisational ombudsmen often receive more complaints than alternative procedures such as anonymous hot-lines.[11]

Since the 1960s, the profession has grown in the United States, and Canada, particularly in corporations, universities, and government agencies. The organizational ombudsman works as a designated neutral party, one who is high-ranking in an organization, but who is not part of executive management. Using an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) or appropriate dispute resolution approach, an organisational ombudsman can provide options to whistleblowers or employees and managers with ethical concerns; provide coaching, shuttle diplomacy, generic solutions (meaning a solution which protects the identity of one individual by applying to a class of people, rather than just for the one individual) and mediation for conflicts; track problem areas; and make recommendations for changes to policies or procedures in support of orderly systems change.

Ombudsman services by country

[edit]For specific ombudspersons or commissioners for children or young people, also see Children's ombudsman.

See also

[edit]- Children's ombudsman – Public authority in charge of children's rights

- Complaint system – Set of procedures used in organizations to address complaints & resolve disputes

- Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI)—Coordinates the relationship between national human right institutions and the United Nations human rights system

- Human rights activists – Person who acts to protect human rights

- Information commissioner – Government role relating to data protection and freedom of information issues

- International Ombudsman Institute (IOI)—Representing 150 public sector independent ombudsman institutions on the national, state, regional and local level around the globe

- Liaison officer – Coordinator and communicator between organizations

- National human rights institution – Type of independent state-based institution

- Ombudsman services by country

References

[edit]- ^ "ombudsman". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "Ombudsman". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "ombudsman" (US) and "ombudsman". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ^ Mahbubur Rahman, Muhammad (July 2011). BCS Bangladesh Affairs (in Bengali). Vol. I & II. Lion Muhammad Gias Uddin. p. 46 (Vol. II).

- ^ Park, Sangyil (2008). Korean Preaching, Han, and Narrative. American University Studies. Series VII. Theology and Religion. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0449-7.

- ^ Pickl, V. (1987). "Islamic Roots of Ombudsman Systems". The Ombudsman Journal.

- ^ McKenna Lang, "A Western King and an Ancient Notion: Reflections on the Origins of Ombudsing", Journal of Conflictology. Archived 22 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Conflictology/article/viewArticle/251703/0 http://openaccess.uoc.edu/webapps/o2/handle/10609/12627

- ^ a b ombudsmän, Riksdagens. "Historik". Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ The Public Complaint's Commission (Amendment) Act No. 21 of 1979.

- ^ Beyer, Jürgen (2014). "The influence of reading room rules on the quality and efficiency of historical research" (PDF). Svensk tidskrift för bibliografi. 8 (3): 125.

- ^ Charles L. Howard, The Organizational Ombudsman: Origins, Roles and Operations, a Legal Guide, ABA, 2010.

External links

[edit]- JPGMOnline.com – 'The role of the ombudsman in biomedical journals', Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, Vol 48, No 4, pp 292–296, 2002

- POGO.org – 'EPA Ombudsman Resigns: Accountability in Handling of Superfund Sites Threatened', Project on Government Oversight (22 April 2002)

- Transparency.org – 'What is an Ombudsman'

- Ombudsman Institutions for the Armed Forces Handbook – 'A practical guide to the role of military ombudsman', Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF)

- Ombudsman Institutions and Minority Issues, Study by the European Centre for Minority Issues

- SÖP Schlichtungsstelle für den öffentlichen Personenverkehr e.V., Ombudsman Institution of Public Transport in Germany

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2017. "The Ombuds and Social Control." The Independent Voice, IOA newsletter, May 2017.

International and regional ombudsman associations

[edit]- Africa

- African Ombudsman Research Centre (AORC), Archived 2023-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

- North America

- Asia

- Asian Ombudsman Association (AOA) – "To promote the concepts of Ombudsmanship and to encourage its development in Asia"

- Australasia

- Europe/N.Africa

- Association of Mediterranean Ombudsmen (AMO)

- Ombudsman Association (formerly the British and Irish Ombudsman Association, BIOA)

- European Network of Ombudspersons for Children (ENOC)

- European Network of Ombudsmen in Higher Education (ENOHE), Archived 30 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine – webpage at Universiteit van Amsterdam

- European Ombudsman Institute (EOI)

- global

Ombudsman directories

[edit]- IOI – International Ombudsman Institute (international directory of ombudsmen)

- Ombuds Blog includes lists of organizational ombuds offices in corporations, academic, governmental, and other organizations

Ombudsman

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Core Functions

Definition and Scope

An ombudsman is a designated, independent public official or office empowered to receive, investigate, and address complaints from individuals or groups concerning maladministration, injustice, or abuse of authority by government entities or public institutions.[6] This role emphasizes neutrality, operating outside direct hierarchical control to safeguard against bureaucratic overreach, with investigations often focusing on procedural fairness, legality, and proportionality in administrative decisions rather than re-adjudicating facts or merits.[7] Unlike judicial bodies, ombudsmen lack coercive authority, relying instead on persuasive reports, recommendations, or referrals to higher authorities for resolution, which promotes voluntary compliance through public scrutiny and moral suasion.[8] The scope of an ombudsman's mandate typically extends to executive and administrative functions of state agencies, local governments, and quasi-public bodies, encompassing issues such as delays, errors, discrimination in service delivery, or unreasonable exercises of discretion.[9] Exclusions commonly include active court proceedings, policy formulation, or private sector disputes unless explicitly legislated otherwise, preserving separation of powers and judicial independence.[10] In practice, this breadth allows ombudsmen to mediate between citizens and the state, fostering accountability without supplanting formal legal channels, though effectiveness hinges on institutional autonomy and resource allocation as defined by enabling statutes.[9]Investigative and Mediatory Powers

The ombudsman typically holds statutory authority to initiate investigations into complaints alleging maladministration, injustice, or unfair treatment by public authorities, often without requiring formal legal proceedings.[11] These investigations may commence upon receipt of a citizen's grievance or, in certain jurisdictions, on the ombudsman's own initiative to address systemic issues. Investigative processes generally involve reviewing records, interviewing relevant parties—including agency personnel—and assessing compliance with administrative laws and procedures, though the ombudsman lacks subpoena power in many systems and relies on voluntary cooperation.[11] [12] All such inquiries are conducted confidentially to protect complainants and encourage candor, with findings culminating in non-binding reports that recommend corrective actions or policy changes.[13] Mediatory powers enable the ombudsman to facilitate informal resolutions between complainants and public entities, emphasizing dialogue and conciliation over adversarial adjudication.[14] Acting as a neutral intermediary, the ombudsman clarifies misunderstandings, explores settlement options, and promotes mutual agreements without imposing decisions, drawing on mediation techniques to de-escalate conflicts.[15] This role extends to organizational ombudsmen, who assist in internal disputes by providing perspective and options confidentially, though they refrain from representing parties or determining fault.[16] Success in mediation often stems from the ombudsman's independence and persuasive influence, such as publicizing unresolved maladministration to legislatures, rather than coercive enforcement.[17] Limitations persist, as ombudsmen generally cannot investigate elected officials or their own appointing bodies, preserving accountability boundaries.[6]Historical Development

Etymology and Linguistic Roots

The term "ombudsman" derives from Swedish ombudsman, literally meaning "representative" or "commissioned man," where ombud signifies a proxy or agent entrusted with a task on behalf of another, and man denotes a person.[18] This Swedish compound entered English usage in the mid-20th century to describe public officials handling citizen grievances, but its linguistic foundation traces to Old Norse umboðsmaðr, a compound of um (meaning "about" or "around," indicating scope or delegation), boð (from bjóða, "to offer" or "command," implying authority or bidding), and maðr ("man" or "person").[2] The Old Norse form denoted an individual acting under commission or proxy, reflecting a historical role of intermediary or envoy in medieval Scandinavian legal and administrative contexts.[19] Cognates appear across North Germanic languages, such as Norwegian ombudsmann and Danish ombudsmand, preserving the core sense of delegated representation while adapting to local phonology and orthography.[20] These variants underscore the term's indigenous Scandinavian heritage, distinct from Latin or Romance influences in European administrative vocabulary, and its adoption internationally has retained the original Swedish form without significant semantic shift.[2]Origins in Sweden (1809)

The office of the Parliamentary Ombudsman, known in Swedish as Justitieombudsmannen, was established on June 6, 1809, as part of Sweden's new Instrument of Government, a constitutional document adopted by the Riksdag of the Estates and ratified by King Charles XIII.[3] This innovation emerged in the aftermath of political turmoil, including the deposition of King Gustav IV Adolf earlier that year, prompting reforms to balance monarchical and parliamentary powers while safeguarding individual rights against state overreach.[21] The Instrument of Government explicitly tasked the Riksdag with appointing an ombudsman "known for his knowledge of the law and exemplary probity" to oversee public administration, particularly the judiciary and civil servants, ensuring adherence to legal statutes and preventing abuses of authority.[4] Unlike the King's Chancellor of Justice (Justitiekanslern), which supervised executive functions under royal appointment, the Parliamentary Ombudsman served as an independent parliamentary check, focusing on prosecuting officials for legal violations and reviewing court proceedings for fairness.[3] This dual oversight mechanism reflected Enlightenment-inspired principles of divided powers and accountability, drawing from earlier precedents like the 1713 royal prosecutor role but formalizing it as a citizen-protective institution amid Sweden's shift toward constitutional monarchy. The ombudsman's mandate included initiating investigations based on complaints or suo motu, issuing critiques, and recommending disciplinary actions, though without direct enforcement powers, relying instead on public reports and parliamentary influence to enforce compliance.[21] The first ombudsman was appointed in 1810, marking the operational inception of the office, which quickly became a model for institutionalizing grievance redress in democratic governance.[3] By embedding this role in the constitution, Sweden pioneered a non-adversarial supervisory body that prioritized systemic legal fidelity over punitive measures, influencing subsequent Nordic adoptions while adapting to Sweden's civil law tradition of administrative scrutiny.[4] Empirical continuity of the institution underscores its foundational design: annual reports to the Riksdag have sustained transparency, with the office evolving minimally in core functions despite expansions in scope over two centuries.[3]Global Adoption and Evolution (19th-20th Centuries)

The ombudsman institution, established in Sweden in 1809, saw minimal international adoption during the 19th century, remaining confined primarily to its Scandinavian origins with no recorded implementations outside Sweden until the early 20th century.[22] Finland adopted a parliamentary ombudsman in 1919 upon gaining independence from Sweden, extending the model to oversee public administration and judicial compliance with laws, though this still limited the institution to Nordic contexts.[23] The concept's evolution during this period emphasized supervisory roles over legality and administrative fairness, but lacked broader appeal amid prevailing monarchical and colonial governance structures that prioritized centralized authority over citizen redress mechanisms.[10] Adoption accelerated in the mid-20th century, beginning with Denmark's establishment of a parliamentary ombudsman in 1955, which marked the onset of global interest by demonstrating the institution's utility in addressing post-World War II demands for administrative accountability without expansive judicial intervention.[24] Norway followed in 1962, refining the role to include proactive inspections of public bodies.[23] New Zealand became the first nation outside Scandinavia to implement an ombudsman in 1962, influenced by recommendations from a parliamentary justice committee that highlighted the Swedish and Danish models as effective counters to bureaucratic overreach in a Westminster-style system.[25] The institution's evolution outside Scandinavia involved adaptations to local constitutional frameworks, such as in the United Kingdom, where the Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration was created in 1967 with a narrower mandate focused on "maladministration" rather than direct legality reviews, requiring complaints to be filtered through members of Parliament.[25] Guyana adopted an ombudsman in 1966 as one of the earliest in the developing world, tailoring it to post-colonial governance needs for citizen protection against executive abuse.[26] By the late 20th century, over 50 countries had established national ombudsman offices, driven by transnational advocacy from figures like Denmark's first ombudsman, Stephan Hurwitz, who promoted the model through international lectures and writings emphasizing its role in fostering democratic oversight without politicization. This spread reflected causal pressures from expanding welfare states and rising public expectations for transparent administration, though implementations varied in independence and enforcement powers, with some critics noting diluted efficacy in politically fragmented systems.[27]Types and Applications

Parliamentary and Governmental Ombudsmen

Parliamentary ombudsmen are independent officials appointed by legislative bodies to oversee the executive branch, public administration, and sometimes judicial actions, ensuring adherence to laws, regulations, and principles of good governance through complaint investigations and systemic reviews. Their core functions include receiving and scrutinizing public complaints about maladministration, abuse of power, or rights violations; conducting inquiries without needing formal charges; and issuing non-binding recommendations, decisions, or reports that carry significant moral and precedential weight to influence administrative behavior.[28] These institutions report annually to parliament, aiding legislative oversight while maintaining operational autonomy from the executive to preserve impartiality.[29] In Sweden, the model originated with the 1809 constitutional reform establishing the Justitieombudsmannen, now comprising four Parliamentary Ombudsmen (JO) elected by the Riksdag for four-year terms, responsible for supervising all public authorities and courts for legal compliance and fairness in proceedings.[30] The JO handled 5,831 complaints in 2023, critiquing agencies in 18% of inspected cases for procedural flaws or undue delays, with decisions serving as binding interpretations for civil servants despite lacking enforcement powers.[30] This structure emphasizes preventive oversight, as JO conducts unannounced inspections and initiates own-motion probes into systemic issues like data protection lapses.[30] Finland's Parliamentary Ombudsman, elected by the Eduskunta for a four-year term renewable once, acts as the supreme guardian of legality, supervising courts, prisons, and administrative bodies while promoting human rights implementation under the constitution's Section 109.[31] Supported by two deputy ombudsmen and legal advisors, the office processed 10,237 complaints in 2022, finding faults in 12% of cases and issuing guidelines that have reduced recurrence rates in areas like welfare decision-making by 25% over five years through targeted recommendations.[32] Independence is structurally ensured via parliamentary appointment and budget, though critics note occasional alignment with legislative majorities in politically sensitive rulings.[33] In the United Kingdom, the Parliamentary Ombudsman, appointed by the Crown on Prime Minister's advice but operationally independent, investigates complaints from constituents via MPs about central government departments' maladministration causing injustice, excluding policy matters or judicial review.[34] Established under the 1967 Parliamentary Commissioner Act, the office resolved 2,500 cases in 2023-2024, upholding 14% of investigated complaints and securing remedies like £1.2 million in redress, though effectiveness is limited by non-binding outcomes and low awareness, with only 1% of potential cases reaching it.[34] Reports to Parliament via the Public Administration Committee enhance accountability, yet empirical data shows persistent implementation gaps, with 40% of recommendations partially followed in systemic reports.[34] Governmental ombudsmen, often synonymous with parliamentary variants in classical models but sometimes denoting executive-focused roles, prioritize scrutiny of bureaucratic agencies over broader legislative oversight, as seen in public sector adaptations where they mediate citizen-administration disputes without direct parliamentary reporting.[6] In jurisdictions like Australia, the Commonwealth Ombudsman—statutorily independent but government-appointed—handles executive complaints across 200+ agencies, investigating 28,000 matters in 2022-2023 and achieving 85% resolution rates pre-litigation, underscoring a causal link between early intervention and reduced court burdens.[35] Distinctions arise in funding and appointment: parliamentary models derive legitimacy from legislatures to counter executive dominance, while governmental ones risk capture if executive influence prevails, as evidenced by lower independence scores in non-Nordic implementations per global benchmarks.[9] Empirical outcomes favor hybrid parliamentary-governmental structures for balancing accessibility with authority, with Nordic examples demonstrating 20-30% higher complaint substantiation rates due to entrenched norms of transparency.[29]Organizational and Sector-Specific Ombudsmen

Organizational ombudsmen operate as designated neutrals within private corporations, universities, non-profits, and other internal structures, providing confidential, informal avenues for employees or members to voice concerns, seek guidance, and resolve disputes without formal escalation.[36][37] These roles emphasize independence from management hierarchies, impartiality in listening and advising, and a focus on early intervention to prevent escalation, often including options analysis, coaching, and facilitated dialogue rather than binding decisions.[38] Key functions include serving as an information resource on policies, channeling feedback to leadership for systemic improvements, and identifying trends in workplace issues like harassment or inefficiency, though they lack authority to investigate formally or impose remedies.[36][39] In practice, organizational ombudsmen have been implemented in entities such as MIT since the 1960s and various U.S. universities, where they handle interpersonal conflicts and bureaucratic navigation, potentially reducing litigation costs by an estimated average of $20,000 per mid-sized firm through informal resolutions.[40][41] Sector-specific ombudsmen, by contrast, typically function externally to address consumer or client disputes in regulated industries, offering independent out-of-court resolution for complaints against providers in areas like finance, insurance, and telecommunications.[8] In the financial sector, schemes such as those outlined by international networks resolve issues involving banking products, payments, and credit, facilitating settlements between individuals, small businesses, and institutions while promoting market confidence without requiring legal proceedings.[42][43] For instance, the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation's Ombudsman, established to act as a neutral liaison, processes inquiries from the public and banking sector on deposit insurance and supervision matters, emphasizing confidentiality and referrals rather than adjudication.[44] These mechanisms often mandate provider participation and can recommend compensation, with empirical benefits including faster resolutions—typically within months versus years in courts—and lower costs, though their effectiveness depends on enforcement powers and jurisdictional scope, as weaker schemes may struggle with systemic enforcement.[45][46] In healthcare and other sectors, analogous roles exist for long-term care advocacy, but financial examples dominate due to higher complaint volumes, with global adoption accelerating post-2008 crisis to bolster trust in volatile markets.[43]Implementation by Jurisdiction

European Models

European ombudsman institutions typically embody a parliamentary model emphasizing independent scrutiny of public administration for legality, fairness, and propriety, though with national adaptations in jurisdiction, appointment, and enforcement mechanisms. In Nordic countries, this model remains closest to the Swedish archetype, extending oversight to administrative bodies, courts, and sometimes law enforcement. Finland's Parliamentary Ombudsman, established by the 1919 Form of Government Act and operational from 1920, supervises officials' adherence to laws and constitutional rights, conducting inspections and handling complaints directly from citizens.[47] Denmark adopted a modified version in 1953 via parliamentary act, focusing primarily on executive maladministration while initially excluding judicial review, with the ombudsman empowered to recommend remedies but lacking coercive authority.[48] The United Kingdom introduced the Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration in 1967 under the Parliamentary Commissioner Act, adapting the model by requiring complaints to be filtered through members of Parliament, thereby limiting direct public access and concentrating on injustice caused by maladministration in central government departments.[49] France's Défenseur des droits, created in 2011 through constitutional amendment and organic law, integrates ombudsman functions with broader mandates to protect citizens' rights in public services, combat discrimination, defend children, and support whistleblowers, appointed by the president for a non-renewable six-year term.[50] Germany eschews a unified federal parliamentary ombudsman, relying instead on the Bundestag's Petitions Committee for citizen grievances and sector-specific offices, such as the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces established in 1951, alongside regional ombudsmen in states like Rhineland-Palatinate since 1974.[51][52] At the European Union level, the European Ombudsman, formalized by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty and first appointed in 1995, investigates allegations of maladministration by EU institutions, bodies, and agencies, promoting transparency and good administrative practices through inquiries, recommendations, and reports to the European Parliament.[53] These institutions across Europe exhibit heterogeneity, with no singular template; variations reflect constitutional traditions, such as direct versus mediated access and inclusion of human rights or anti-discrimination roles, yet all prioritize non-adversarial resolution and accountability without binding judicial powers. By 2025, every EU member state incorporates some ombudsman mechanism, often aligned with Council of Europe standards for democratic oversight.[54]North American and Other Regional Variations

In the United States, ombudsman offices lack a centralized national parliamentary model akin to those in Europe, instead operating as specialized entities within federal agencies or sectors to address administrative grievances through mediation and advocacy. The Office of the National Ombudsman in the Small Business Administration, established under the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-121), assists small businesses in resolving regulatory disputes with agencies, emphasizing informal resolution without binding authority.[55] Similarly, Long-Term Care Ombudsman programs, authorized by amendments to the Older Americans Act in 1975, advocate for residents in long-term care facilities, investigating complaints and promoting resident rights across all 50 states and territories by 2023.[56] These U.S. implementations, which proliferated from the mid-1960s onward, prioritize accessibility and confidentiality but often face limitations in independence due to agency embedding, contrasting with Europe's broader investigative mandates.[57] Canada features a decentralized network of ombudsman institutions at provincial, territorial, and federal levels, with no singular national overseer, reflecting federalism's influence on administrative accountability. The earliest provincial offices emerged in Alberta and New Brunswick in 1967, positioning Canada as an early adopter outside Europe and empowering legislatures to scrutinize executive actions.[58] For example, Ontario's Ombudsman handles over 30,000 inquiries annually against provincial government and delegated public bodies, focusing on fairness in services like health and education.[59] Federally, specialized roles include the Procurement Ombudsman, reviewing contract awards since 2008, and the National Defence and Canadian Forces Ombudsman, addressing military complaints independently since 1998.[60] [61] These entities emphasize systemic recommendations over enforcement, with empirical reviews noting higher resolution rates in targeted sectors compared to broader models.[62] In Latin America, ombudsman institutions—frequently styled as "Defensor del Pueblo" or human rights procurators—arose during 1980s democratic reforms to protect rights amid post-authoritarian transitions, diverging from European administrative foci by integrating constitutional human rights defense. Guatemala established the region's first such office in 1985 under its new constitution, tasking it with monitoring public administration and rights compliance.[63] By the 1990s, over a dozen countries, including Argentina, Peru, and Colombia, adopted similar bodies, often with prosecutorial powers to challenge state violations, though effectiveness varies due to political interference risks documented in regional assessments.[64] Australasian variations, such as Australia's Commonwealth Ombudsman founded in 1977, extend to federal and state levels for agency oversight, incorporating own-motion investigations and annual reports to parliament, while Pacific islands adapt scaled-down models for resource-limited governance.[65] In Asia, implementations hybridize classical elements with local needs, as in hybrid anti-corruption-ombudsman roles in Indonesia and the Philippines, where mandates blend maladministration probes with integrity enforcement, reflecting cultural emphases on hierarchical accountability over individual complaint resolution.[66]Effectiveness and Empirical Outcomes

Achievements in Accountability and Resolution

Ombudsmen institutions have achieved notable success in resolving individual complaints against public authorities, often resulting in remedies for complainants and corrective actions by investigated bodies. In the United Kingdom, the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) accepted 36,886 complaints for consideration in 2023-2024, conducting primary or detailed investigations on 8,835 cases, of which 494 decisions identified failings or injustice warranting recommendations.[67] These outcomes included £341,937 in recommended financial payments and 1,120 total recommendations for service improvements, many of which public bodies implemented to address systemic issues such as delays in state pension notifications and patient safety lapses in healthcare.[67] In Sweden, the Parliamentary Ombudsmen (JO) supervise compliance with laws and administrative fairness, handling over 2,000 cases in the Chief Parliamentary Ombudsman's purview alone during 2024, issuing criticisms that compel authorities to rectify maladministration, such as inadequate documentation by customs officials or accessibility failures in employment services.[68] [69] These interventions have historically fostered a culture of accountability, with JO decisions influencing procedural reforms; for example, in social insurance matters concluded during 2013-2014, over 15% involved some level of criticism leading to internal agency adjustments.[70] Sector-specific ombudsmen have similarly driven resolutions with measurable impacts. The U.S. Long-Term Care Ombudsman programs achieved complaint resolution rates of 58.7% in nursing facilities and 54.4% in board-and-care settings, based on analyses of state-level data, contributing to enhanced resident protections through substantiated interventions.[71] In financial services, the UK Financial Ombudsman Service upheld 37% of resolved complaints in 2023-2024, facilitating redress and policy refinements by firms.[72] Across jurisdictions, high acceptance rates of ombudsman recommendations—often exceeding 90% in parliamentary models—underscore their role in enforcing accountability without coercive powers, relying instead on persuasive authority and public scrutiny.Criticisms, Limitations, and Empirical Shortcomings

Ombudsmen typically lack statutory authority to enforce recommendations, relying instead on moral suasion, public reporting, and political pressure to secure compliance from investigated entities.[6] This non-binding nature limits their ability to compel systemic change, as agencies may ignore findings without legal repercussions.[29] In practice, such constraints have led to variable implementation rates; for instance, in Malta's public sector, only 57% of the 87 sustained recommendations issued by the Ombudsman in 2024 were fully implemented by public bodies, with 17% rejected outright and 23% remaining pending.[73] Empirical assessments reveal further shortcomings in resolution efficacy. A 1995 Institute of Medicine review of U.S. state long-term care ombudsman programs found that 51% operated below full implementation capacity due to insufficient resources, correlating with lower complaint resolution rates and facility visitation coverage.[74] Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman's 2023-2024 data indicated that while nearly 60% of recommended remedies were initially accepted by councils, over 20% faced delayed execution beyond agreed timelines, undermining timely accountability.[75] These outcomes highlight a causal gap between investigative findings and remedial action, often exacerbated by resource shortages and institutional resistance. Jurisdictional boundaries further constrain ombudsman scope, excluding private sector disputes, cabinet-level decisions, judicial proceedings, and national security matters in many systems.[13] This fragmented coverage can render the institution ineffective for pervasive grievances, such as those involving commercial entities or high-level policy, where complainants must seek alternative, often costlier, avenues like courts.[76] Critics argue this design fosters a perception of superficial oversight, with ombudsmen serving more as advisory bodies than robust enforcers, potentially eroding public trust when complex cases yield protracted or inconclusive results without enforceable remedies.[77] In federal contexts like the United States, institutional analyses have described such offices as prone to futility due to entrenched bureaucratic obstacles and lack of visibility, limiting broader empirical impact on administrative reform.[77]Contemporary Trends and Challenges

Developments Since 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted ombudsman institutions globally to adapt their operations, with many offices reporting a surge in complaints related to public health measures, administrative delays, and crisis decision-making. For instance, the UK Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman investigated systemic issues in COVID-19 management, identifying trends in policy implementation failures through individual casework and influencing subsequent reforms. Similarly, an international survey by the Ombudsman Association highlighted leadership challenges, including resource strains and the need for rapid policy advocacy amid lockdowns, affecting over 100 ombudsman offices.[78] Post-pandemic, ombudsman roles increasingly incorporated digital tools and hybrid practices to enhance accessibility and efficiency. In higher education and organizational settings, the shift to virtual mediation and remote consultations rose significantly, enabling part-time and interim positions while expanding reach to geographically dispersed users.[79] This adaptation addressed backlogs exacerbated by the crisis, with empirical data from U.S. academic ombuds programs showing improved resolution rates through technology-driven grievance handling.[80] Several jurisdictions pursued remit expansions and strategic updates to tackle emerging issues like artificial intelligence governance and ethical lobbying. The European Ombudsman launched its "Towards 2024" strategy in December 2020, emphasizing transparency in EU decision-making and setting global benchmarks for lobbying ethics amid post-COVID recovery funding.[81] Nationally, Ireland's Ombudsman outlined a 2025 strategy to drive remit growth in consumer and public sectors, while New Zealand's Chief Ombudsman updated its international engagement plan for 2024-2026 to foster cross-border accountability.[82][83] The International Ombudsman Institute's 2024-2025 reforms further promoted capacity-building in AI oversight, citing increased complaints on algorithmic biases in public administration.[84][85] Challenges persisted regarding independence and resource adequacy, with offices like Australia's Commonwealth Ombudsman noting in its 2025-26 plan the need to counter political pressures amid rising caseloads from regulatory changes.[86] In specialized domains, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve's ombudsman, procedural amendments in 2020 strengthened appeal mechanisms for supervisory disputes, reflecting broader empirical pushes for evidentiary rigor in resolutions.[87] These developments underscore a trend toward proactive, data-informed evolution, though empirical evaluations, including those from the OECD, indicate varied effectiveness tied to institutional autonomy.[9]Ongoing Debates on Independence and Scope

A central debate concerns the extent to which ombudsmen maintain genuine independence from the executive or legislative branches they oversee, particularly amid political pressures and resource constraints. Critics argue that appointment processes, often controlled by parliaments or governments, can prioritize loyalty over impartiality, as seen in cases where ombudsmen face dismissal threats for investigating high-level officials.[88][78] In the Philippines, for example, a 2025 controversy highlighted questions over the ombudsman's authority to remove sitting lawmakers, reviving arguments that such powers undermine separation of branches without robust safeguards.[89] Empirical analyses indicate that funding dependencies exacerbate this, with ombudsmen in resource-scarce environments sometimes deferring to government priorities to secure budgets, thereby eroding public trust.[90] Proponents counter that parliamentary linkages, as in Scandinavian models, provide insulation via multi-party consensus, though recent global surveys by the International Ombudsman Institute (IOI) reveal increasing attacks on offices championing human rights in polarized contexts.[78] On scope, ongoing discussions focus on the tension between broadening mandates to address contemporary issues—like corruption, human rights violations, and emerging technologies—and the risk of institutional overload or diluted focus. Since the early 2020s, many ombudsmen have assumed multiple roles beyond traditional maladministration redress, including anti-corruption enforcement and vulnerable population protections, as evidenced by IOI reports on mandate expansions in over 20 jurisdictions.[88][91] This shift, while enhancing relevance, has led to criticisms of ineffectiveness due to limited coercive powers, relying instead on persuasion and recommendations, which succeed in only 10-15% of investigated cases per Danish Ombudsman data analogs applied globally.[77] Debates intensified post-2020 with calls to extend scope into AI governance and digital rights, as discussed at the 2025 International Ombudsman Conference, where panels questioned whether such additions strain resources without corresponding independence enhancements.[92] A 2025 UN General Assembly resolution affirmed ombudsmen's expanded role in sustainable development goals, yet highlighted implementation gaps in jurisdictions with overlapping mandates, potentially fragmenting accountability efforts.[93]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ombudsman