Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Orans

View on Wikipedia

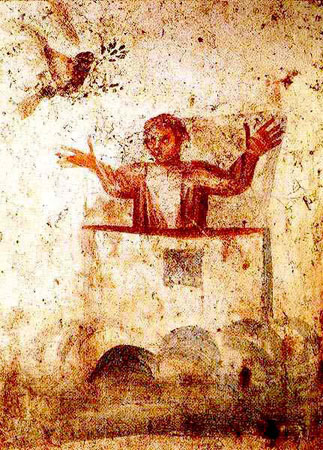

Orans, a loanword from Medieval Latin orans (Latin: [ˈoː.raːns]) translated as "one who is praying or pleading", also orant or orante, as well as lifting up holy hands, is a posture or bodily attitude of prayer, usually standing, with the elbows close to the sides of the body and with the hands outstretched sideways, palms up.[1][2][3] The orans posture of prayer has a Scriptural basis in 1 Timothy 2 (1 Timothy 2:8): "I desire, then, that in every place the men should pray, lifting up holy hands without anger or argument" (NRSV).[1][2][3]

It was common in early Christianity and can frequently be seen in early Christian art, being advised by several early Church Fathers, who saw it as "the outline of the cross".[1][3] In modern times, the orans position is still preserved in Oriental Orthodoxy, as when Coptic Christian believers pray the seven canonical hours of the Agpeya at fixed prayer times.[4] The orans also occurs within parts of the Catholic, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, and Anglican liturgies, Pentecostal and charismatic worship, and the ascetical practices of some religious groups.[2][3]

History

[edit]The orans posture is widespread in the art of the Ancient Near East, both in the Levant and in Egypt, from at least the Late Bronze Age. It was in origin a gesture of supplication or submission shown towards a deity (or the image of a deity) upon entering a temple.[5]

The orans position is seen throughout the Old Testament, in Isaiah as well as in certain Psalms (such as Psalm 134:2–3, Psalm 28:2, Psalm 63:4–5, Psalm 141:2, Psalm 143:6).[6] It has been argued that the gesture was adopted by Early Christianity from Second Temple Judaism.[7] References in the New Testament are 1 Timothy 2:8, and Hebrews 12:12–13.[7]

The biblical ordinance of lifting hands up in prayer was advised by many early Christian apologists, including Marcus Minucius Felix, Clement of Rome, Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian.[1][2] Christians saw the position as representing the posture of Christ on the Cross; therefore, it was the favorite of early Christians. Some scholars also assert that the deference this pose exhibits—with the outstretched hands showing a sort of submission to a religious power—is intertwined with Roman ideas of pietas; this encapsulates notions of family values, civic honor and charitable behavior.[8][9]

In Oriental Orthodoxy, Coptic Christian believers pray the seven canonical hours of the Agpeya at fixed prayer times in the orans position while standing.[4] In Western Christianity, until at least the ninth century, the posture was used by entire congregations during celebrations of the Eucharist.[10][3] By the twelfth century, however, the joining of hands began to replace the orans posture as the preferred position for prayer. The orans posture has continued to be used at certain points in the liturgies of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox and Churches.[3] In the Catholic Church, Masses in the Latin liturgical rites see the celebrating priest prays the orations, the Eucharistic Prayer, and the Lord's Prayer in the gesture of orans; in the Maronite Church's Holy Qurbana, the congregation together with the priest lift up their hands in the orans posture during various parts of the liturgy, such as the anaphora and Lord's Prayer.[11][3] The orans gesture survived the Reformation and was preserved in the liturgy of the Lutheran and Anglican Churches.

The orans posture experienced a revival within Pentecostalism and Charismatic Christianity under the umbrella of the contemporary worship movement of the mid-20th century.[10][12][13]

Depictions in art

[edit]

Orans was common in early Sumerian cultures: "...it appears that Sumerian people might have a statue carved to represent themselves and do their worshipping for them—in their place, as a stand in. An inscription on one such statue translates, 'It offers prayers.' Another inscription says, 'Statue, say unto my king (god)..."[14] The custom of praying in antiquity with outstretched, raised arms was common to both Jews and Gentiles, and indeed the iconographic type of the Orans was itself strongly influenced by classic representations. But the meaning of the orans of Christian art is quite different from that of its prototypes.[15] It is possible that medieval representations of a diminutive body, figure of the soul, issuing from the mouths of the dying were reminiscences of the orans as a symbol of the soul. Other theories imply a less metaphorical view, instead arguing that the heavily feminine iconography of orans sheds light on the state of female involvement in the early Church.[8]

Numerous Biblical figures, for instance, depicted in the catacombs of Rome—Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, and Daniel in the lion's den—are pictured asking the Lord to deliver the soul of the person on whose tombs they are depicted as he once delivered the particular personage represented. But besides these Biblical orans figures there exist in the catacombs many ideal figures (153 in all) in the ancient attitude of prayer,[15] representing the deceased's soul in heaven, praying for their friends on earth.[16] One of the most convincing proofs that the orans was regarded as a symbol of the soul is an ancient lead medal in the Vatican Museum showing the martyr St. Lawrence, under torture, while his soul, in the form of a female orans, is just leaving the body. An arcosolium in the Ostrianum cemetery represents an orans with a petition for her intercession: Victoriæ Virgini … Pete … The Acts of St. Cecilia speaks of souls leaving the body like virgins: Vidit egredientes animas eorum de corporibus, quasi virgines de thalamo ("He saw their souls coming out of their bodies, like virgins from the chamber"), and so also the Acts of Sts. Peter and Marcellinus.[15] Other academic opinions, however, disagree with the metaphorical nature of the above theories; citing the large amount of female orans figures and their common characteristics, they argue that the prevalence of non-male figures indicates unacknowledged female leadership in the early church.[8][17] While writings focusing female leaders is rare in early Christianity, scholars look to art to provide a more holistic picture; in particular, women appearing to supervise eucharist—in orans position—in catacomb iconography leads some to propose the existence of female leadership in the church.[8][17] This represents a less metaphorical lens than that of the feminine orans representing the soul.

The earlier orantes were depicted in the simplest garb, and without any striking individual traits, but in the fourth century the figures become richly adorned, and of marked individuality, an indication of the approach of historic art. One of the most remarkable figures of the orans cycle, dating from the early fourth century, is interpreted by Wilpert as the Blessed Virgin interceding for the friends of the deceased. Directly in front of Mary is a boy, not in the orans attitude and supposed to be the Divine Child, while to the right and left are monograms of Christ.[15]

The Platytéra, a hagiographic depiction on the Virgin Mary as Our Lady of the Sign which is standing in the orans gesture, usually placed on the half-dome above the altar of Byzantine-style churches, and facing down the nave.

Gallery

[edit]-

Orans (catacombs of Rome), first half of IV c.

-

Orans of Kyiv. Mosaic. XI c.

-

Orans in Kyiv Saint Sophia cathedral

-

Our Lady of the Sign icon. Veliky Novgorod. First half of XII c.

-

Inexhaustible Chalice icon. Serpukhov. XIX c.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Couchman, Judith (5 March 2010). The Mystery of the Cross: Bringing Ancient Christian Images to Life. InterVarsity Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8308-7917-5.

Because early Christians were Jewish, they naturally lifted their hands in prayer, like the veiled orans figures in the catacombs. The apostle Paul advised the earliest Christians, "I want men everywhere to lift up holy hands in prayer, without anger or disputing" (1 Tim 2:8) and early church literature indicates the widespread practice of this prayer position. In the first through third centuries, Marcus Minucius Felix, Clement of Rome, Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian either advised Christians to lift up hands in prayer, or at least mentioned the practice.

- ^ a b c d Wainwright, Geoffrey (1997). For Our Salvation: Two Approaches to the Work of Christ. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8028-0846-2.

The piety shows itself in the informal signing of one's body with the sign of the cross, in what 1 Timothy 2:8 calls "lifting holy hands" in prayer (a gesture stretching from the orans pictures in the catacombs to modern Pentecostalism), in penitential or submissive kneeling, in reverential genuflections, in the ascetical practices suggested by the apostle Paul's athletic imagery (1 Cor. 9:24-27; 1 Tim. 6:6-16; 2 Tim. 4:7f).

- ^ a b c d e f g "Why do we extend our arms when praying the Our Father and at other times during the Maronite anaphora?". Living Maronite. 27 November 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

This is sometimes referred to as the Orans posture. The posture is explicitly directed by the presently used Maronite Qorbono. The posture has in its origins an association with prayer. It can be found in the Old Testament. In Psalm 141 we pray: "Let my prayer be counted as incense before you, and the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice." The posture is referred to in the New Testament at 1 Timothy 2:8, in the instructions concerning prayer: "I desire, then, that in every place the men should pray, lifting up holy hands without anger or argument;" We see the posture in the early Church catacomb icons as depicted here. The icon perhaps gives us the best indication of why the posture is presently used in the Maronite Mass.

- ^ a b Dawood, Bishoy (8 December 2013). "Stand, Bow, Prostrate: The Prayerful Body of Coptic Christianity: Clarion Review". Clarion Review. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

Standing facing the East is the most frequent prayer position. The person praying usually holds his or her hands outwards in the 'orans' position, which is a common Christian position of prayer, frequently portrayed in ancient Christian art, including in Coptic iconography. At other times, hands may be kept down to the sides or held together as a sign of standing in humility before God. Some people choose to hold a cross in their hands as they stand in the orans position; in this case, the sign of the cross traced over the body ends with kissing the cross.

- ^ David M. Calabro, "Gestures of Praise: Lifting and Spreading the Hands in Biblical Prayer", in David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick, and Matthew J. Grey (eds.),Ascending the Mountain of the Lord Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament (2013).

- ^ Byrum, Enoch Edwin (1904). "Ordinances of the Bible: Showing the Ordinances that Have Been Abolished, and Those Still in Vogue". Gospel Trumpet Company. p. 114.

- ^ a b Emminghaus, Johannes H. (1997). The Eucharist: Essence, Form, Celebration. Liturgical Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8146-1036-7.

This Jewish gesture of prayer was apparently adopted by Christians for private as well as communal prayer.

- ^ a b c d Cohick, L. H., & Hughes, A. B. "Christian Women in Catacomb Art." Christian women in the patristic world: Their influence, authority, and legacy in the second through Fifth Centuries, 65-88. Baker Academic. 2017.

- ^ Lamont., Brown, Peter Robert (1988). The body and society : men, women and sexual renunciation in early christianity. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-06100-5. OCLC 799698391.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Stephen Burns, SCM Studyguide to Liturgy (Hymns Ancient & Modern Ltd, 2006), 62.

- ^ "Liturgical Gestures." New Catholic Encyclopedia. second edition, volume 8. Detroit: Gale, 2003. 646-650. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 February 2012.

- ^ Paul Harvey and Philip Goff, The Columbia documentary history of religion in America since 1945 (Columbia University Press, 2005), 347.

- ^ Larry Witham, Who shall lead them?: the future of ministry in America (Oxford University Press, 1 July 2005), 134.

- ^ Benton, DiYanni, J. R, R (2008). Arts and Culture: An Introduction to the Humanities. Upper Saddle, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-536-41910-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Wilpert "Ein Cyklus christologischer Gemälde aus der Katakombe der Heiligen Petrus und Marcellinus" (Freiburg, 1891);

- ^ a b Torjesen, K. (2020). The Early Christian Orans: An Artistic Representation of Women's Liturgical Prayer and Prophecy. In Women Preachers and Prophets through Two Millennia of Christianity (pp. 42-56). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Orans". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Orans". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.