Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

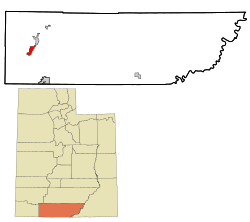

Orderville, Utah

View on Wikipedia

Orderville is a town in western Kane County, Utah, United States. The population was 598 at the 2020 census.[4] The town was founded and operated under the United Order of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This system allowed the community to flourish for some time, but ultimately ended in 1885.[5]

Key Information

History

[edit]

Distribution of goods and services

[edit]Orderville was established at the direction of LDS Church president Brigham Young in 1875 specifically to live the United Order, a voluntary form of communal living defined by Joseph Smith. Orderville was settled primarily by destitute refugees from failed settlements on the Muddy River in Nevada. When it was settled, Orderville included 335 acres (136 ha) of land and contained 18 houses, 19 oxen, 103 cows, 43 horses, 500 sheep, 30 hogs, 400 chickens, and 30,000 feet of lumber. The settlement began completely debt-free.[6]

Homes were one- or two-room apartment units arranged around the town square. Community dining halls and public buildings were constructed. The dining hall began operation for the town on July 24, 1875, and prepared meals for more than 80 families. Men ate first, followed by women and children. Meal times were scheduled at 7 am, 12 pm, and 6 pm.[6]

Under the United Order, no person in Orderville could have private property, as it was all considered to be God's land. Each person was made a steward over some personal effects, and every family a steward over a home. During the first two years, the settlers worked without receiving income. They were allowed to use supplies and take food as needed. The bishop of Orderville oversaw the distribution of goods. Credits were recorded for all work done by men, women, and children and used to obtain needed materials and keep track of the labor done in the settlement. In 1877, the order began a price system to replace the credit system, and monetary values were assigned to all labor and goods. At the beginning of each year, debts were forgiven, and those who had earned a surplus voluntarily gave it back to the order.[6]

The settlers there grew their own crops and had some small farms surrounding the settlement. They also used local materials to make their own soap, brooms, buckets, furniture, etc. Orderville settlers produced silk thread and wove it into articles of clothing. They later opened up their own tannery. There were blacksmiths, clerks, artists, musicians, and other professions. Priddy Meeks came to Orderville to serve as the settlement's doctor in 1876. Ten percent of the net increase of Orderville was donated to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to follow the law of tithing.[6]

Management

[edit]The group was managed by an annually-elected Board of Management consisting of nine men who bought and sold goods on behalf of the entire settlement. They also directed labor performed by the settlers. The president was the bishop, and the vice presidents were usually his counselors. Thus, there was a very close connection between spiritual and secular. Orderville was divided into 33 departments, and each year members of the board met with the department directors to determine what the needs were and how many workers would be proportioned to the department.[6]

In order for new members to join, the entire community had to vote. A new member was welcomed into Orderville only if the admission vote was a two-thirds majority. All newcomers were interviewed to determine their motives for wanting to join the society. They were also asked a number of questions regarding their moral and spiritual habits. New members had to agree to follow the strict standards and conditions of the settlement, including no swearing and giving up tobacco, tea, and coffee. Brigham Young cautioned against "allowing those whom might become parasites on the body from becoming members." When members wanted to leave, they were given back the capital they had initially invested along with their surplus credits for that year. If the members leaving had debts, they were usually forgiven.[6]

Success

[edit]Although the United Order was practiced in many Utah communities during the late 1870s, Orderville was unique in both the level of success it experienced under the communal living style, and in the duration of the experiment. In the course of a few years, Orderville grew into a thriving, self-sufficient community. The success and relative wealth of the community attracted more settlers, and Orderville grew to about 700 people. Orderville not only provided for the needs of its population, but produced a significant surplus for sale to other communities, which was used to purchase additional land and equipment. The extreme poverty of these settlers likely contributed significantly to their devotion to the principles of the United Order.[6]

End of the Order

[edit]The Order continued in Orderville for approximately 10 years. During the early 1870s, the economic environment improved in southern Utah. The discovery of silver nearby led to railroad facilities and an influx of people to the area. Local farmers were able to find a market for their goods and gained more profit. The neighboring towns that had once bought goods from Orderville now found themselves able to import materials from other regions. Orderville goods became "old fashioned". The youth of Orderville envied the youth in other communities, creating friction within the community. Due to this friction, the communal dining system was abandoned in 1880. Three years later the value system assigned to labor was adjusted, introducing a level of inequality that had not existed before. Families were also given their own spending money. These changes led to tension and much internal disruption of the Order. While these internal conflicts and changes eventually would have led to the end of the practice of the United Order in Orderville, national legislation ensured it. In 1885, the enforcement of the Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act of 1882 effectively ended the order by jailing many of the order's leaders and driving many of the others underground. Members of the community held an auction using their credits as payment. Orderville continued its tannery, wool factory, and sheep enterprise, which were overseen by the Board of Management until 1889.[6]

Orderville's current leadership is headed by Mayor Lyle Goulding.[7]

Geography

[edit]Orderville is in western Kane County within the Long Valley, formed by the East Fork of the Virgin River. U.S. Route 89 passes through the town, leading north 4 miles (6 km) to Glendale and 45 miles (72 km) to Panguitch, and south 21 miles (34 km) to Kanab, the Kane county seat.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 9.2 square miles (23.7 km2), all land.[8] Its current limits include the former incorporated communities of Mount Carmel and Mount Carmel Junction.[9][10] From Mount Carmel Junction, Utah State Route 9 leads west 23 miles (37 km) to Zion National Park.

Climate

[edit]This region experiences warm (but not hot) and dry summers, with no average monthly temperatures above 73.1 °F (22.8 °C). According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Orderville has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate, abbreviated "Csb" on climate maps.[11]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 514 | — | |

| 1890 | 289 | −43.8% | |

| 1900 | 418 | 44.6% | |

| 1910 | 380 | −9.1% | |

| 1920 | 378 | −0.5% | |

| 1930 | 439 | 16.1% | |

| 1940 | 441 | 0.5% | |

| 1950 | 371 | −15.9% | |

| 1960 | 398 | 7.3% | |

| 1970 | 399 | 0.3% | |

| 1980 | 423 | 6.0% | |

| 1990 | 422 | −0.2% | |

| 2000 | 596 | 41.2% | |

| 2010 | 577 | −3.2% | |

| 2020 | 598 | 3.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 577 people, 209 households, and 155 families residing in the town. The racial makeup of the town was 98.1% White, 0.2% Native American, 0.2% from other races, and .7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.4% of the population.[2]

There were 209 households, out of which 25% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.1% were married couples living together, 7.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.8% were non-families. 30.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.76 and the average family size was 3.28.[2]

In the town, the population was spread out, with 30.6% under the age of 18, 5% from 20 to 24, 16.8% from 25 to 44, 23% from 45 to 64, and 17.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.5 years. The total female population was 49.7% with 50.3% being male.[2]

The median income for a household in the town was $51,838 in 2015. Males had a median income of $29,375 versus $15,000 for females. 6.2% of people in Orderville were below the poverty line. 17.9% of the population does not have health insurance. The median value for a house is $125,800.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Census Bureau profile: Orderville town, Utah". United States Census Bureau. May 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2025.

- ^ May, Dean L. "The United Order Movement". Utah History Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arrington, Leonard J. (March 1954). "Orderville, Utah: A Pioneer Mormon Experiment in Economic Organization". Utah State Agricultural College Monograph Series. 2 (2).

- ^ "Directory". Town of Orderville. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Orderville town, Utah". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "TIGERweb: Orderville, Utah". Geography Division, U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "Mt. Carmel, UT". Acme Mapper. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "Climate Summary for Orderville, Utah".

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Orderville town, Utah". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Unofficial town website

- Guide to Zion National Park Archived May 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Zion National Park Archived May 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Utah History Encyclopedia

Orderville, Utah

View on GrokipediaOrderville is a small town in Kane County, southern Utah, United States, with a population of 595 as of the 2020 United States Census.[1] The town was founded in 1875 under the direction of Brigham Young, second president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as a settlement operating under the United Order, a voluntary communal economic system aimed at implementing principles of consecration and stewardship to achieve self-sufficiency and eliminate poverty.[2][3] Orderville's implementation of the United Order, which emphasized collective labor, shared resources, and assigned work, proved relatively successful and enduring, lasting over a decade until its dissolution in the mid-1880s amid broader economic pressures and the shift toward private enterprise.[4] Today, the town functions as a rural community near Zion National Park, deriving economic support from tourism centered on hiking, slot canyons, and proximity to natural attractions along U.S. Route 89.[5]

History

Founding and Early Settlement

The Long Valley region, where Orderville is located, saw initial Mormon exploration in 1852 by a party led by John D. Lee under direction from Parowan leaders.[6] Formal settlement efforts began in spring 1864 when a group of pioneers from southern Utah communities, including Parowan and St. George, established temporary camps along the East Fork of the Virgin River.[7] Priddy Meeks, a physician and early Mormon settler, became the first permanent resident in the lower Long Valley area, constructing a dugout home in the hillside near the current Orderville site.[6] These early outposts faced significant challenges from Native American Paiute tribes amid broader regional tensions exacerbated by the Black Hawk War.[8] By 1866, settlers evacuated the valley due to threats of attack, abandoning structures and returning to safer northern settlements like Parowan.[9] Resettlement resumed around 1871 as conflicts subsided, with families reoccupying sites and establishing small farming and ranching operations focused on subsistence agriculture in the fertile valley soils.[8] These pioneers, primarily from Kane and Washington counties, laid the groundwork for community development, constructing basic log cabins and irrigation ditches to harness the Virgin River's waters for crops such as wheat, corn, and vegetables.[10] By mid-1875, the growing cluster of homes prompted formal organization under church direction, setting the stage for Orderville's distinct communal structure.[2]Establishment of the United Order

The United Order in Orderville was formally organized on July 14, 1875, by Mormon settlers in Kane County, Utah, as an extension of earlier communal experiments in the Long Valley region, including the Mount Carmel United Order. Approximately 30 families, who had begun arriving in the area around 1870–1871, pooled their resources—including cash, livestock, tools, and land claims—into a collective entity governed by principles of consecration and stewardship derived from Latter-day Saint doctrine.[11][3] This establishment occurred under the direct oversight of Brigham Young, president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who had initiated the broader United Order movement in 1874 to promote economic self-sufficiency and equality amid post-Civil War challenges like debt and speculation in Utah Territory. Young dispatched representatives, including apostle Brigham Young Jr., to encourage and regulate such orders, viewing Orderville's adoption as a model for implementing the biblical "Order of Enoch" through shared labor and property distribution. Participants formalized their commitment via rebaptism, surrendering individual titles to assets while receiving assigned stewardships based on family needs and community roles.[4][12][13] Initial leadership included a board of directors elected from among the members, with Israel Hoyt serving as an early presiding figure in the local order before transitions to figures like Ebenezer Robinson as bishop. The community's layout was planned communally, with uniform housing arranged in a rectangular formation to symbolize equality, and all production directed toward collective sustenance rather than personal profit. This structure distinguished Orderville from less rigorous united orders elsewhere, emphasizing total consecration without private ownership.[14][15][16]Operations and Communal Practices

The United Order in Orderville operated as a highly centralized communal system from its establishment in 1875, with an elected board of directors overseeing all facets of production, distribution, and daily activities to emulate the biblical "Order of Enoch."[4] All property was consecrated to the collective upon entry, eliminating private ownership; incoming members deeded assets to the Order, which assigned stewardships based on family needs, while surplus contributed to communal growth, expanding total assets from $21,551 for 80 families in 1875 to $69,562 by 1879 and nearly $80,000 by 1883.[4] [2] Labor was divided by a board assigning roles according to age, sex, and aptitude, with an 1877 accounting system valuing work uniformly—initially independent of output—to foster equality, though this shifted to unequal wages and partial private stewardships by 1883 amid emerging inefficiencies.[4] [2] Communal practices emphasized uniformity and interdependence to curb individualism and pride. Residents resided in standardized apartments within a U-shaped fort of "shanties," dined together in a central hall serving up to 300 pounds of bread daily until its destruction by flood in 1880, and were summoned for meals by a blacksmith playing hymns on a coronet.[14] [4] [17] Clothing consisted of locally produced homespun wool and cotton uniforms, manufactured in the Order's woolen and cotton factories, with later allowances for store-bought items reflecting gradual relaxations.[4] [17] Children assisted in distributing goods to families, and work credits accrued daily could be redeemed at the bishop's storehouse, with annual audits balancing individual contributions against allotments to maintain equity.[14] [17] Economic operations centered on self-sufficiency through diverse industries, including a tannery, gristmill, sawmill, molasses mill, bucket factory, silk production, dairying, broom and hat making, extensive farming of orchards and gardens, and livestock herding of sheep and cattle across ranches in Kane County and grazing rights on the Buckskin Mountains.[14] These enterprises, such as the woolen mill and sheep company leased post-1885 until 1900, supported the community's population growth to 700–800 by 1876 and generated goods like leather products and fabric for internal use and trade.[14] [2] The system prioritized collective welfare over personal gain, with baptismal covenants reinforcing labor for the community's benefit, though federal pressures like the 1882 Edmunds Act ultimately contributed to its 1885 dissolution.[17] [4]Challenges, Controversies, and Decline

Despite its relative success compared to other United Order experiments, Orderville faced mounting internal challenges by the late 1870s, including disputes over work assignments, water rights, and the burdens imposed by less diligent members who strained communal resources.[17] [18] A notable controversy arose in 1880 with the "pants rebellion," where young men, dissatisfied with the uniform homespun wool trousers mandated by the Order, traded communal wool for store-bought pants from Nephi, Utah, sparking conflict with the Board of Management over external influences and individualism.[19] This incident highlighted growing youth discontent and the appeal of market goods, leading to adjustments like allowing external cotton cloth for clothing.[19] [17] Economic prosperity, with assets rising from $21,551 in 1875 to $80,000 by 1883, paradoxically fueled jealousy and calls for inequality, prompting shifts such as an 1877 accounting system valuing labor and commodities uniformly, the end of communal dining after a 1880 flood destroyed facilities, and adoption of partial stewardship with unequal wages in 1883 under apostle Erastus Snow's recommendation.[4] [2] These modifications diluted the pure communal model, reflecting causal pressures from human incentives and practical inefficiencies in enforcing equality amid varying productivity.[2] [18] External factors accelerated decline, particularly the death of Brigham Young in 1877, which removed centralized oversight, and the Edmunds Act of 1882, which prosecuted polygamous leaders, imprisoning or exiling figures like bishop Thomas Chamberlain and decimating governance.[4] [17] [2] Federal anti-polygamy campaigns threatened property confiscation, prompting apostles Brigham Young Jr. and Heber J. Grant to counsel disincorporation in 1885.[17] [18] The Order formally dissolved that year via community vote, with assets like the tannery, woolen mill, and sheep ranch auctioned or distributed by 1889, marking the transition to private ownership, though the corporation lingered until lapsing in 1904.[2] [4]Dissolution and Transition to Private Enterprise

The communal system in Orderville began eroding in the late 1870s due to internal frictions over equal distribution and external economic pressures, culminating in significant changes by the early 1880s.[2][4] A devastating flood on January 23, 1880, destroyed the central dining hall and kitchens, which had symbolized the Order's unity by serving up to 700 communal meals daily; this event effectively ended the practice of shared eating, as families shifted to preparing food in their individual homes.[4][2] In response to growing inefficiencies and dissatisfaction with strict equalization, Apostle Erastus Snow, overseeing southern Utah stakes, recommended in 1883 the adoption of an unequal wage system and partial stewardships, allowing families to receive assigned plots of land for personal cultivation and retention of surplus produce beyond basic needs.[4][2] These reforms marked the initial transition from full communalism, with Order enterprises such as the tannery, woolen mill, and sheep operations increasingly leased to individual operators who paid fees to the collective, fostering elements of private initiative within the framework.[2][4] The Edmunds Act of 1882, federal legislation criminalizing polygamy and intensifying scrutiny on Mormon economic cooperatives, further strained the system by leading to the arrest, imprisonment, or exile of several Orderville leaders, exacerbating leadership vacuums and internal disruptions.[2] The United Order formally dissolved in 1885 under directive from central church authorities, who advised disbandment to mitigate federal antagonism toward Mormon communal practices and polygamy.[4][2] Most assets, including land and improvements, were auctioned off that year, enabling former members to repurchase properties approximating their original contributions or stewardships, thereby reestablishing private ownership and individual farming operations.[20][19] Community-held enterprises persisted under collective oversight until 1889, after which the incorporating corporation lapsed in 1904, completing the shift to a private enterprise model centered on agriculture and small-scale industry.[2] Post-dissolution, Orderville transitioned into a conventional rural farming community, with residents relying on private landholdings for sustenance and trade.[12]Geography

Location and Physical Features

Orderville occupies a position in western Kane County, southern Utah, within the Long Valley region formed by the East Fork of the Virgin River.[2] This valley setting places the town amid the Colorado Plateau's characteristic geological structures, including elevated plateaus, deep canyons, mesas, and buttes.[21] The terrain reflects the broader physiography of Kane County, dominated by eroded sandstone formations and arid highlands.[21] Geographic coordinates for Orderville center at approximately 37.28°N latitude and 112.64°W longitude.[22] The town's elevation averages around 5,460 feet (1,664 meters) above sea level, contributing to a high-desert environment with surrounding mountainous elevations rising sharply.[23] Proximity to Zion National Park westward and Bryce Canyon National Park northeastward underscores the area's rugged topography and scenic relief, shaped by fluvial erosion and tectonic uplift over millions of years.[15]Climate

Orderville lies at an elevation of 5,460 feet (1,664 m) above sea level, which moderates temperatures compared to surrounding lower-elevation deserts while contributing to low humidity and significant daily temperature swings. The locality experiences a semi-arid climate with hot, dry summers and cold, occasionally snowy winters, receiving limited precipitation that supports sparse vegetation dominated by sagebrush and junipers. Average annual precipitation measures 16.81 inches (42.7 cm), concentrated primarily from late fall through spring, with summer months typically seeing less than 0.8 inches (2 cm) combined. Snowfall totals average 29 inches (73.7 cm) yearly, mostly occurring between November and March.[24] Average temperatures range from a yearly high of 67°F (19°C) to a low of 36°F (2°C), based on 1991–2020 normals. Winters feature frequent freezes, with January averages of 46.6°F (8.1°C) highs and 20.5°F (-6.4°C) lows, while July brings peak warmth at 92°F (33°C) highs and 59°F (15°C) lows. Extreme heat can exceed 100°F (38°C) in summer, and subzero (°F) conditions occur in winter, though prolonged cold snaps are mitigated by elevation-driven solar radiation.[24]| Month | Avg. High (°F) | Avg. Low (°F) | Avg. Precip. (in.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 46.6 | 20.5 | 1.5 |

| February | 49.8 | 23.6 | 1.6 |

| March | 57.0 | 28.6 | 1.4 |

| April | 65.7 | 33.3 | 0.9 |

| May | 75.4 | 41.5 | 0.7 |

| June | 86.7 | 49.6 | 0.4 |

| July | 92.1 | 58.3 | 0.5 |

| August | 90.0 | 56.3 | 0.7 |

| September | 82.6 | 48.4 | 0.8 |

| October | 71.1 | 37.6 | 1.0 |

| November | 56.5 | 27.9 | 1.1 |

| December | 47.3 | 20.8 | 1.4 |