Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sequence homology

View on Wikipedia

Sequence homology is the biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences, defined in terms of shared ancestry in the evolutionary history of life. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of three phenomena: either a speciation event (orthologs), or a duplication event (paralogs), or else a horizontal (or lateral) gene transfer event (xenologs).[1]

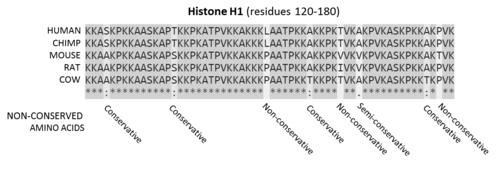

Homology among DNA, RNA, or proteins is typically inferred from their nucleotide or amino acid sequence similarity. Significant similarity is strong evidence that two sequences are related by evolutionary changes from a common ancestral sequence. Alignments of multiple sequences are used to indicate which regions of each sequence are homologous.

Identity, similarity, and conservation

[edit]

The term "percent homology" is often used to mean "sequence similarity", that is the percentage of identical residues (percent identity), or the percentage of residues conserved with similar physicochemical properties (percent similarity), e.g. leucine and isoleucine, is usually used to "quantify the homology." Based on the definition of homology specified above this terminology is incorrect since sequence similarity is the observation, homology is the conclusion.[3] Sequences are either homologous or not.[3] This involves that the term "percent homology" is a misnomer.[4]

As with morphological and anatomical structures, sequence similarity might occur because of convergent evolution, or, as with shorter sequences, by chance, meaning that they are not homologous. Homologous sequence regions are also called conserved. This is not to be confused with conservation in amino acid sequences, where the amino acid at a specific position has been substituted with a different one that has functionally equivalent physicochemical properties.

Partial homology can occur where a segment of the compared sequences has a shared origin, while the rest does not. Such partial homology may result from a gene fusion event.

Beyond sequence similarity

[edit]Proteins are known to conserve their tertiary structure more strongly than their amino acid sequences. Two distantly related proteins can have minimal or even undetectable sequence similarity, yet have highly similar folds that can be compared via structural alignment. Examples of these proteins used to be only discovered by experimental structual determination methods. Modern protein structure prediction methods such as AlphaFold2 allow possible homologs to be identified without wet lab work.[5]

RNA is also known to conserve tertiary structure more strongly than primary structure. RNA secondary structure prediction was found to be helpful in human-to-mouse comparison.[6]

Orthology

[edit]

Homologous sequences are orthologous if they are inferred to be descended from the same ancestral sequence separated by a speciation event: when a species diverges into two separate species, the copies of a single gene in the two resulting species are said to be orthologous. Orthologs, or orthologous genes, are genes in different species that originated by vertical descent from a single gene of the last common ancestor. The term "ortholog" was coined in 1970 by the molecular evolutionist Walter Fitch.[7]

For instance, the plant Flu regulatory protein is present both in Arabidopsis (multicellular higher plant) and Chlamydomonas (single cell green algae). The Chlamydomonas version is more complex: it crosses the membrane twice rather than once, contains additional domains and undergoes alternative splicing. However, it can fully substitute the much simpler Arabidopsis protein, if transferred from algae to plant genome by means of genetic engineering. Significant sequence similarity and shared functional domains indicate that these two genes are orthologous genes,[8] inherited from the shared ancestor.

Orthology is strictly defined in terms of ancestry. Given that the exact ancestry of genes in different organisms is difficult to ascertain due to gene duplication and genome rearrangement events, the strongest evidence that two similar genes are orthologous is usually found by carrying out phylogenetic analysis of the gene lineage. Orthologs often, but not always, have the same function.[9]

Orthologous sequences provide useful information in taxonomic classification and phylogenetic studies of organisms. The pattern of genetic divergence can be used to trace the relatedness of organisms. Two organisms that are very closely related are likely to display very similar DNA sequences between two orthologs. Conversely, an organism that is further removed evolutionarily from another organism is likely to display a greater divergence in the sequence of the orthologs being studied.[citation needed]

Databases of orthologous genes and de novo orthology inference tools

[edit]Given their tremendous importance for biology and bioinformatics, orthologous genes have been organized in several specialized databases that provide tools to identify and analyze orthologous gene sequences. These resources employ approaches that can be generally classified into those that use heuristic analysis of all pairwise sequence comparisons, and those that use phylogenetic methods. Sequence comparison methods were first pioneered in the COGs database in 1997.[10] These methods have been extended and automated in twelve different databases the most advanced being AYbRAH Analyzing Yeasts by Reconstructing Ancestry of Homologs[11] as well as these following databases right now. Some tools predict orthologous de novo from the input protein sequences, might not provide any Database. Among these tools are SonicParanoid and OrthoFinder.

- eggNOG[12][13]

- GreenPhylDB[14][15] for plants

- InParanoid[16][17] focuses on pairwise ortholog relationships

- OHNOLOGS[18][19] is a repository of the genes retained from whole genome duplications in the vertebrate genomes including human and mouse.

- OMA[20]

- OrthoDB[21] appreciates that the orthology concept is relative to different speciation points by providing a hierarchy of orthologs along the species tree.

- OrthoInspector[22] is a repository of orthologous genes for 4753 organisms covering the three domains of life

- OrthologID[23][24]

- OrthoMaM[25][26][27] for mammals

- OrthoMCL[28][29]

- Roundup[30]

- SonicParanoid[31][32] is a graph based method that uses machine learning to reduce execution times and infer orthologs at the domain level.

Tree-based phylogenetic approaches aim to distinguish speciation from gene duplication events by comparing gene trees with species trees, as implemented in databases and software tools such as:

- LOFT[33]

- TreeFam[34][35]

- OrthoFinder[36]

A third category of hybrid approaches uses both heuristic and phylogenetic methods to construct clusters and determine trees, for example:

Paralogy

[edit]Paralogous genes are genes that are related via duplication events in the last common ancestor (LCA) of the species being compared. They result from the mutation of duplicated genes during separate speciation events. When descendants from the LCA share mutated homologs of the original duplicated genes then those genes are considered paralogs.[1]

As an example, in the LCA, one gene (gene A) may get duplicated to make a separate similar gene (gene B), those two genes will continue to get passed to subsequent generations. During speciation, one environment will favor a mutation in gene A (gene A1), producing a new species with genes A1 and B. Then in a separate speciation event, one environment will favor a mutation in gene B (gene B1) giving rise to a new species with genes A and B1. The descendants' genes A1 and B1 are paralogous to each other because they are homologs that are related via a duplication event in the last common ancestor of the two species.[1]

Additional classifications of paralogs include alloparalogs (out-paralogs) and symparalogs (in-paralogs). Alloparalogs are paralogs that evolved from gene duplications that preceded the given speciation event. In other words, alloparalogs are paralogs that evolved from duplication events that happened in the LCA of the organisms being compared. The example above is an example alloparalogy. Symparalogs are paralogs that evolved from gene duplication of paralogous genes in subsequent speciation events. From the example above, if the descendant with genes A1 and B underwent another speciation event where gene A1 duplicated, the new species would have genes B, A1a, and A1b. In this example, genes A1a and A1b are symparalogs.[1]

Paralogous genes can shape the structure of whole genomes and thus explain genome evolution to a large extent. Examples include the Homeobox (Hox) genes in animals. These genes not only underwent gene duplications within chromosomes but also whole genome duplications. As a result, Hox genes in most vertebrates are clustered across multiple chromosomes with the HoxA-D clusters being the best studied.[41]

Another example are the globin genes which encode myoglobin and hemoglobin and are considered to be ancient paralogs. Similarly, the four known classes of hemoglobins (hemoglobin A, hemoglobin A2, hemoglobin B, and hemoglobin F) are paralogs of each other. While each of these proteins serves the same basic function of oxygen transport, they have already diverged slightly in function: fetal hemoglobin (hemoglobin F) has a higher affinity for oxygen than adult hemoglobin. Function is not always conserved, however. Human angiogenin diverged from ribonuclease, for example, and while the two paralogs remain similar in tertiary structure, their functions within the cell are now quite different.[citation needed]

It is often asserted that orthologs are more functionally similar than paralogs of similar divergence, but several papers have challenged this notion.[42][43][44]

Regulation

[edit]Paralogs are often regulated differently, e.g. by having different tissue-specific expression patterns (see Hox genes). However, they can also be regulated differently on the protein level. For instance, Bacillus subtilis encodes two paralogues of glutamate dehydrogenase: GudB is constitutively transcribed whereas RocG is tightly regulated. In their active, oligomeric states, both enzymes show similar enzymatic rates. However, swaps of enzymes and promoters cause severe fitness losses, thus indicating promoter–enzyme coevolution. Characterization of the proteins shows that, compared to RocG, GudB's enzymatic activity is highly dependent on glutamate and pH.[45]

Paralogous chromosomal regions

[edit]Sometimes, large regions of chromosomes share gene content similar to other chromosomal regions within the same genome.[46] They are well characterised in the human genome, where they have been used as evidence to support the 2R hypothesis. Sets of duplicated, triplicated and quadruplicated genes, with the related genes on different chromosomes, are deduced to be remnants from genome or chromosomal duplications. A set of paralogy regions is together called a paralogon.[47] Well-studied sets of paralogy regions include regions of human chromosome 2, 7, 12 and 17 containing Hox gene clusters, collagen genes, keratin genes and other duplicated genes,[48] regions of human chromosomes 4, 5, 8 and 10 containing neuropeptide receptor genes, NK class homeobox genes and many more gene families,[49][50][51] and parts of human chromosomes 13, 4, 5 and X containing the ParaHox genes and their neighbors.[52] The Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on human chromosome 6 has paralogy regions on chromosomes 1, 9 and 19.[53] Much of the human genome seems to be assignable to paralogy regions.[54]

Ohnology

[edit]Ohnologous genes are paralogous genes that have originated by a process of whole-genome duplication. The name was first given in honour of Susumu Ohno by Ken Wolfe.[55] Ohnologues are useful for evolutionary analysis because all ohnologues in a genome have been diverging for the same length of time (since their common origin in the whole genome duplication). Ohnologues are also known to show greater association with cancers, dominant genetic disorders, and pathogenic copy number variations.[56][57][58][59][60]

Xenology

[edit]Homologs resulting from horizontal gene transfer between two organisms are termed xenologs. Xenologs can have different functions if the new environment is vastly different for the horizontally moving gene. In general, though, xenologs typically have similar function in both organisms. The term was coined by Walter Fitch.[7]

Homoeology

[edit]Homoeologous (also spelled homeologous) chromosomes or parts of chromosomes are those brought together following inter-species hybridization and allopolyploidization to form a hybrid genome, and whose relationship was completely homologous in an ancestral species.[61] In allopolyploids, the homologous chromosomes within each parental sub-genome should pair faithfully during meiosis, leading to disomic inheritance; however in some allopolyploids, the homoeologous chromosomes of the parental genomes may be nearly as similar to one another as the homologous chromosomes, leading to tetrasomic inheritance (four chromosomes pairing at meiosis), intergenomic recombination, and reduced fertility.[citation needed]

Gametology

[edit]Gametology denotes the relationship between homologous genes on non-recombining, opposite sex chromosomes. The term was coined by García-Moreno and Mindell.[62] 2000. Gametologs result from the origination of genetic sex determination and barriers to recombination between sex chromosomes. Examples of gametologs include CHDW and CHDZ in birds.[62]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Koonin EV (2005). "Orthologs, paralogs, and evolutionary genomics". Annual Review of Genetics. 39: 309–38. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.114725. PMID 16285863.

- ^ "Clustal FAQ #Symbols". Clustal. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ a b Reeck GR, de Haën C, Teller DC, Doolittle RF, Fitch WM, Dickerson RE, et al. (August 1987). ""Homology" in proteins and nucleic acids: a terminology muddle and a way out of it". Cell. 50 (5): 667. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90322-9. PMID 3621342. S2CID 42949514.

- ^ Holman C (January 2004). "Protein Similarity Score: A Simplified Version of the Blast Score as a Superior Alternative to Percent Identity for Claiming Genuses of Related Protein Sequences". Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal. 21 (1): 55. ISSN 0882-3383.

- ^ Zhang, S; Zhang, T; Fu, Y (1 December 2023). "Proteome-wide structural analysis quantifies structural conservation across distant species". Genome Research. 33 (11): 1975–1993. doi:10.1101/gr.277771.123. PMC 10760455. PMID 37993136.

- ^ Torarinsson E, Sawera M, Havgaard JH, Fredholm M, Gorodkin J (2006). "Thousands of corresponding human and mouse genomic regions unalignable in primary sequence contain common RNA structure". Genome Res. 16 (7): 885–9. doi:10.1101/gr.5226606. PMC 1484455. PMID 16751343.

- ^ a b Fitch WM (June 1970). "Distinguishing homologous from analogous proteins". Systematic Zoology. 19 (2): 99–113. doi:10.2307/2412448. JSTOR 2412448. PMID 5449325.

Where the homology is the result of gene duplication so that both copies have descended side by side during the history of an organism (for example, a and b hemoglobin) the genes should be called paralogous (para = in parallel). Where the homology is the result of speciation so that the history of the gene reflects the history of the species (for example a hemoglobin in man and mouse) the genes should be called orthologous (ortho = exact).

- ^ Falciatore A, Merendino L, Barneche F, Ceol M, Meskauskiene R, Apel K, Rochaix JD (January 2005). "The FLP proteins act as regulators of chlorophyll synthesis in response to light and plastid signals in Chlamydomonas". Genes & Development. 19 (1): 176–87. doi:10.1101/gad.321305. PMC 540235. PMID 15630026.

- ^ Fang G, Bhardwaj N, Robilotto R, Gerstein MB (March 2010). "Getting started in gene orthology and functional analysis". PLOS Computational Biology. 6 (3) e1000703. Bibcode:2010PLSCB...6E0703F. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000703. PMC 2845645. PMID 20361041.

- ^ COGs: Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins

Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ (October 1997). "A genomic perspective on protein families". Science. 278 (5338): 631–7. Bibcode:1997Sci...278..631T. doi:10.1126/science.278.5338.631. PMID 9381173. - ^ Correia K, Yu SM, Mahadevan R (January 2019). "AYbRAH: a curated ortholog database for yeasts and fungi spanning 600 million years of evolution". Database. 2019. doi:10.1093/database/baz022. PMC 6425859. PMID 30893420.

- ^ eggNOG: evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups

Muller J, Szklarczyk D, Julien P, Letunic I, Roth A, Kuhn M, et al. (January 2010). "eggNOG v2.0: extending the evolutionary genealogy of genes with enhanced non-supervised orthologous groups, species and functional annotations". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (Database issue): D190-5. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp951. PMC 2808932. PMID 19900971. - ^ Powell S, Forslund K, Szklarczyk D, Trachana K, Roth A, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. (January 2014). "eggNOG v4.0: nested orthology inference across 3686 organisms". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (Database issue): D231-9. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1253. PMC 3964997. PMID 24297252.

- ^ GreenPhylDB

Conte MG, Gaillard S, Lanau N, Rouard M, Périn C (January 2008). "GreenPhylDB: a database for plant comparative genomics". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (Database issue): D991-8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm934. PMC 2238940. PMID 17986457. - ^ Rouard M, Guignon V, Aluome C, Laporte MA, Droc G, Walde C, et al. (January 2011). "GreenPhylDB v2.0: comparative and functional genomics in plants". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Database issue): D1095-102. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq811. PMC 3013755. PMID 20864446.

- ^ Inparanoid: Eukaryotic Ortholog Groups

Ostlund G, Schmitt T, Forslund K, Köstler T, Messina DN, Roopra S, et al. (January 2010). "InParanoid 7: new algorithms and tools for eukaryotic orthology analysis". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (Database issue): D196-203. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp931. PMC 2808972. PMID 19892828. - ^ Sonnhammer EL, Östlund G (January 2015). "InParanoid 8: orthology analysis between 273 proteomes, mostly eukaryotic". Nucleic Acids Research. 43 (Database issue): D234-9. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1203. PMC 4383983. PMID 25429972.

- ^ Singh PP, Arora J, Isambert H (July 2015). "Identification of Ohnolog Genes Originating from Whole Genome Duplication in Early Vertebrates, Based on Synteny Comparison across Multiple Genomes". PLOS Computational Biology. 11 (7) e1004394. Bibcode:2015PLSCB..11E4394S. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004394. PMC 4504502. PMID 26181593.

- ^ "Vertebrate Ohnologs". ohnologs.curie.fr. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ^ Altenhoff AM, Glover NM, Train CM, Kaleb K, Warwick Vesztrocy A, Dylus D, et al. (January 2018). "The OMA orthology database in 2018: retrieving evolutionary relationships among all domains of life through richer web and programmatic interfaces". Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (D1): D477 – D485. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx1019. PMC 5753216. PMID 29106550.

- ^ Zdobnov EM, Tegenfeldt F, Kuznetsov D, Waterhouse RM, Simão FA, Ioannidis P, et al. (January 2017). "OrthoDB v9.1: cataloging evolutionary and functional annotations for animal, fungal, plant, archaeal, bacterial and viral orthologs". Nucleic Acids Research. 45 (D1): D744 – D749. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw1119. PMC 5210582. PMID 27899580.

- ^ Nevers Y, Kress A, Defosset A, Ripp R, Linard B, Thompson JD, et al. (January 2019). "OrthoInspector 3.0: open portal for comparative genomics". Nucleic Acids Research. 47 (D1): D411 – D418. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1068. PMC 6323921. PMID 30380106.

- ^ OrthologID

Chiu JC, Lee EK, Egan MG, Sarkar IN, Coruzzi GM, DeSalle R (March 2006). "OrthologID: automation of genome-scale ortholog identification within a parsimony framework". Bioinformatics. 22 (6): 699–707. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btk040. PMID 16410324. - ^ Egan M, Lee EK, Chiu JC, Coruzzi G, Desalle R (2009). "Gene orthology assessment with OrthologID". In Posada D (ed.). Bioinformatics for DNA Sequence Analysis. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 537. Humana Press. pp. 23–38. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-251-9_2. ISBN 978-1-59745-251-9. PMID 19378138.

- ^ OrthoMaM

Ranwez V, Delsuc F, Ranwez S, Belkhir K, Tilak MK, Douzery EJ (November 2007). "OrthoMaM: a database of orthologous genomic markers for placental mammal phylogenetics". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 241. Bibcode:2007BMCEE...7..241R. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-241. PMC 2249597. PMID 18053139. - ^ Douzery EJ, Scornavacca C, Romiguier J, Belkhir K, Galtier N, Delsuc F, Ranwez V (July 2014). "OrthoMaM v8: a database of orthologous exons and coding sequences for comparative genomics in mammals". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (7): 1923–8. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu132. PMID 24723423.

- ^ Scornavacca C, Belkhir K, Lopez J, Dernat R, Delsuc F, Douzery EJ, Ranwez V (April 2019). "OrthoMaM v10: Scaling-Up Orthologous Coding Sequence and Exon Alignments with More than One Hundred Mammalian Genomes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (4): 861–862. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz015. PMC 6445298. PMID 30698751.

- ^ OrthoMCL: Identification of Ortholog Groups for Eukaryotic Genomes

Chen F, Mackey AJ, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS (January 2006). "OrthoMCL-DB: querying a comprehensive multi-species collection of ortholog groups". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (Database issue): D363-8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj123. PMC 1347485. PMID 16381887. - ^ Fischer S, Brunk BP, Chen F, Gao X, Harb OS, Iodice JB, et al. (September 2011). "Using OrthoMCL to assign proteins to OrthoMCL-DB groups or to cluster proteomes into new ortholog groups". Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. Chapter 6 (1): Unit 6.12.1–19. doi:10.1002/0471250953.bi0612s35. ISBN 978-0-471-25095-1. PMC 3196566. PMID 21901743.

- ^ Roundup

Deluca TF, Wu IH, Pu J, Monaghan T, Peshkin L, Singh S, Wall DP (August 2006). "Roundup: a multi-genome repository of orthologs and evolutionary distances". Bioinformatics. 22 (16): 2044–6. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl286. PMID 16777906. - ^ Cosentino, Salvatore; Iwasaki, Wataru (1 January 2019). "SonicParanoid: fast, accurate and easy orthology inference". Bioinformatics. 35 (1): 149–151. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty631. PMC 6298048. PMID 30032301.

- ^ Cosentino, Salvatore; Sriswasdi, Sira; Iwasaki, Wataru (25 July 2024). "SonicParanoid2: fast, accurate, and comprehensive orthology inference with machine learning and language models". Genome Biology. 25 (1): 195. doi:10.1186/s13059-024-03298-4. PMC 11270883. PMID 39054525.

- ^ TreeFam: Tree families database

van der Heijden RT, Snel B, van Noort V, Huynen MA (March 2007). "Orthology prediction at scalable resolution by phylogenetic tree analysis". BMC Bioinformatics. 8: 83. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-83. PMC 1838432. PMID 17346331. - ^ TreeFam: Tree families database

Ruan J, Li H, Chen Z, Coghlan A, Coin LJ, Guo Y, et al. (January 2008). "TreeFam: 2008 Update". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (Database issue): D735-40. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1005. PMC 2238856. PMID 18056084. - ^ Schreiber F, Patricio M, Muffato M, Pignatelli M, Bateman A (January 2014). "TreeFam v9: a new website, more species and orthology-on-the-fly". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (Database issue): D922-5. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1055. PMC 3965059. PMID 24194607.

- ^ OrthoFinder: Orthologs from gene trees

Emms DM, Kelly S (November 2019). "OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics". Genome Biology. 20 (1): 238. doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. PMC 6857279. PMID 31727128. - ^ Vilella AJ, Severin J, Ureta-Vidal A, Heng L, Durbin R, Birney E (February 2009). "EnsemblCompara GeneTrees: Complete, duplication-aware phylogenetic trees in vertebrates". Genome Research. 19 (2): 327–35. doi:10.1101/gr.073585.107. PMC 2652215. PMID 19029536.

- ^ Thanki AS, Soranzo N, Haerty W, Davey RP (March 2018). "GeneSeqToFamily: a Galaxy workflow to find gene families based on the Ensembl Compara GeneTrees pipeline". GigaScience. 7 (3): 1–10. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giy005. PMC 5863215. PMID 29425291.

- ^ Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, et al. (January 2011). "Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Database issue): D38-51. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1172. PMC 3013733. PMID 21097890.

- ^ Fulton DL, Li YY, Laird MR, Horsman BG, Roche FM, Brinkman FS (May 2006). "Improving the specificity of high-throughput ortholog prediction". BMC Bioinformatics. 7: 270. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-7-270. PMC 1524997. PMID 16729895.

- ^ a b Zakany J, Duboule D (August 2007). "The role of Hox genes during vertebrate limb development". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 17 (4): 359–66. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.011. PMID 17644373.

- ^ Studer RA, Robinson-Rechavi M (May 2009). "How confident can we be that orthologs are similar, but paralogs differ?". Trends in Genetics. 25 (5): 210–6. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2009.03.004. PMID 19368988.

- ^ Nehrt NL, Clark WT, Radivojac P, Hahn MW (June 2011). "Testing the ortholog conjecture with comparative functional genomic data from mammals". PLOS Computational Biology. 7 (6) e1002073. Bibcode:2011PLSCB...7E2073N. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002073. PMC 3111532. PMID 21695233.

- ^ Eisen J (20 September 2011). "Special Guest Post & Discussion Invitation from Matthew Hahn on Ortholog Conjecture Paper".

- ^ Noda-Garcia L, Romero Romero ML, Longo LM, Kolodkin-Gal I, Tawfik DS (July 2017). "Bacilli glutamate dehydrogenases diverged via coevolution of transcription and enzyme regulation". EMBO Reports. 18 (7): 1139–1149. doi:10.15252/embr.201743990. PMC 5494520. PMID 28468957.

- ^ Lundin LG (April 1993). "Evolution of the vertebrate genome as reflected in paralogous chromosomal regions in man and the house mouse". Genomics. 16 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1006/geno.1993.1133. PMID 8486346.

- ^ Coulier F, Popovici C, Villet R, Birnbaum D (December 2000). "MetaHox gene clusters". The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 288 (4): 345–51. Bibcode:2000JEZ...288..345C. doi:10.1002/1097-010X(20001215)288:4<345::AID-JEZ7>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 11144283.

- ^ Ruddle FH, Bentley KL, Murtha MT, Risch N (1994). "Gene loss and gain in the evolution of the vertebrates". Development. 1994: 155–61. doi:10.1242/dev.1994.Supplement.155. PMID 7579516.

- ^ Pébusque MJ, Coulier F, Birnbaum D, Pontarotti P (September 1998). "Ancient large-scale genome duplications: phylogenetic and linkage analyses shed light on chordate genome evolution". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 15 (9): 1145–59. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026022. PMID 9729879.

- ^ Larsson TA, Olsson F, Sundstrom G, Lundin LG, Brenner S, Venkatesh B, Larhammar D (June 2008). "Early vertebrate chromosome duplications and the evolution of the neuropeptide Y receptor gene regions". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8 (1): 184. Bibcode:2008BMCEE...8..184L. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-184. PMC 2453138. PMID 18578868.

- ^ Pollard SL, Holland PW (September 2000). "Evidence for 14 homeobox gene clusters in human genome ancestry". Current Biology. 10 (17): 1059–62. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.1059P. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00676-X. PMID 10996074. S2CID 32135432.

- ^ Mulley JF, Chiu CH, Holland PW (July 2006). "Breakup of a homeobox cluster after genome duplication in teleosts". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (27): 10369–10372. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10310369M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600341103. PMC 1502464. PMID 16801555.

- ^ Flajnik MF, Kasahara M (September 2001). "Comparative genomics of the MHC: glimpses into the evolution of the adaptive immune system". Immunity. 15 (3): 351–62. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00198-4. PMID 11567626.

- ^ McLysaght A, Hokamp K, Wolfe KH (June 2002). "Extensive genomic duplication during early chordate evolution". Nature Genetics. 31 (2): 200–4. doi:10.1038/ng884. PMID 12032567. S2CID 8263376.

- ^ Wolfe K (May 2000). "Robustness--it's not where you think it is". Nature Genetics. 25 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1038/75560. PMID 10802639. S2CID 85257685.

- ^ Singh PP, Affeldt S, Cascone I, Selimoglu R, Camonis J, Isambert H (November 2012). "On the expansion of "dangerous" gene repertoires by whole-genome duplications in early vertebrates". Cell Reports. 2 (5): 1387–98. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.034. PMID 23168259.

- ^ Malaguti G, Singh PP, Isambert H (May 2014). "On the retention of gene duplicates prone to dominant deleterious mutations". Theoretical Population Biology. 93: 38–51. Bibcode:2014TPBio..93...38M. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2014.01.004. PMID 24530892.

- ^ Singh PP, Affeldt S, Malaguti G, Isambert H (July 2014). "Human dominant disease genes are enriched in paralogs originating from whole genome duplication". PLOS Computational Biology. 10 (7) e1003754. Bibcode:2014PLSCB..10E3754S. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003754. PMC 4117431. PMID 25080083.

- ^ McLysaght A, Makino T, Grayton HM, Tropeano M, Mitchell KJ, Vassos E, Collier DA (January 2014). "Ohnologs are overrepresented in pathogenic copy number mutations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (1): 361–6. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111..361M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1309324111. PMC 3890797. PMID 24368850.

- ^ Makino T, McLysaght A (May 2010). "Ohnologs in the human genome are dosage balanced and frequently associated with disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (20): 9270–4. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9270M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914697107. PMC 2889102. PMID 20439718.

- ^ Glover NM, Redestig H, Dessimoz C (July 2016). "Homoeologs: What Are They and How Do We Infer Them?". Trends in Plant Science. 21 (7). Cell Press: 609–621. Bibcode:2016TPS....21..609G. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2016.02.005. PMC 4920642. PMID 27021699.

- ^ a b García-Moreno J, Mindell DP (December 2000). "Rooting a phylogeny with homologous genes on opposite sex chromosomes (gametologs): a case study using avian CHD". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 17 (12): 1826–32. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026283. PMID 11110898.