Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Genetic engineering

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Genetic engineering |

|---|

|

| Genetically modified organisms |

| History and regulation |

| Process |

| Applications |

| Controversies |

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including the transfer of genes within and across species boundaries to produce improved or novel organisms. New DNA is obtained by either isolating and copying the genetic material of interest using recombinant DNA methods or by artificially synthesising the DNA. A construct is usually created and used to insert this DNA into the host organism. The first recombinant DNA molecule was made by Paul Berg in 1972 by combining DNA from the monkey virus SV40 with the lambda virus. As well as inserting genes, the process can be used to remove, or "knock out", genes. The new DNA can either be inserted randomly or targeted to a specific part of the genome.[1]

An organism that is generated through genetic engineering is considered to be genetically modified (GM) and the resulting entity is a genetically modified organism (GMO). The first GMO was a bacterium generated by Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen in 1973. Rudolf Jaenisch created the first GM animal when he inserted foreign DNA into a mouse in 1974. The first company to focus on genetic engineering, Genentech, was founded in 1976 and started the production of human proteins. Genetically engineered human insulin was produced in 1978 and insulin-producing bacteria were commercialised in 1982. Genetically modified food has been sold since 1994, with the release of the Flavr Savr tomato. The Flavr Savr was engineered to have a longer shelf life, but most current GM crops are modified to increase resistance to insects and herbicides. GloFish, the first GMO designed as a pet, was sold in the United States in December 2003. In 2016 salmon modified with a growth hormone were sold.

Genetic engineering has been applied in numerous fields including research, medicine, industrial biotechnology and agriculture. In research, GMOs are used to study gene function and expression through loss of function, gain of function, tracking and expression experiments. By knocking out genes responsible for certain conditions it is possible to create animal model organisms of human diseases. As well as producing hormones, vaccines and other drugs, genetic engineering has the potential to cure genetic diseases through gene therapy. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells are used in industrial genetic engineering. Additionally mRNA vaccines are made through genetic engineering to prevent infections by viruses such as COVID-19. The same techniques that are used to produce drugs can also have industrial applications such as producing enzymes for laundry detergent, cheeses and other products.

The rise of commercialised genetically modified crops has provided economic benefit to farmers in many different countries, but has also been the source of most of the controversy surrounding the technology. This has been present since its early use; the first field trials were destroyed by anti-GM activists. Although there is a scientific consensus that food derived from GMO crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food, critics consider GM food safety a leading concern. Gene flow, impact on non-target organisms, control of the food supply and intellectual property rights have also been raised as potential issues. These concerns have led to the development of a regulatory framework, which started in 1975. It has led to an international treaty, the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, that was adopted in 2000. Individual countries have developed their own regulatory systems regarding GMOs, with the most marked differences occurring between the United States and Europe.

Genetic engineering: Process of inserting new genetic information into existing cells in order to modify a specific organism for the purpose of changing its characteristics.

Overview

[edit]

Genetic engineering is a process that alters the genetic structure of an organism by either removing or introducing DNA, or modifying existing genetic material in situ. Unlike traditional animal and plant breeding, which involves doing multiple crosses and then selecting for the organism with the desired phenotype, genetic engineering takes the gene directly from one organism and delivers it to the other. This is much faster, can be used to insert any genes from any organism (even ones from different domains) and prevents other undesirable genes from also being added.[4]

Genetic engineering could potentially fix severe genetic disorders in humans by replacing the defective gene with a functioning one.[5] It is an important tool in research that allows the function of specific genes to be studied.[6] Drugs, vaccines and other products have been harvested from organisms engineered to produce them.[7] Crops have been developed that aid food security by increasing yield, nutritional value and tolerance to environmental stresses.[8]

The DNA can be introduced directly into the host organism or into a cell that is then fused or hybridised with the host.[9] This relies on recombinant nucleic acid techniques to form new combinations of heritable genetic material followed by the incorporation of that material either indirectly through a vector system or directly through micro-injection, macro-injection or micro-encapsulation.

Genetic engineering does not normally include traditional breeding, in vitro fertilisation, induction of polyploidy, mutagenesis and cell fusion techniques that do not use recombinant nucleic acids or a genetically modified organism in the process.[9] However, some broad definitions of genetic engineering include selective breeding.[10] Cloning and stem cell research, although not considered genetic engineering,[11] are closely related and genetic engineering can be used within them.[12] Synthetic biology is an emerging discipline that takes genetic engineering a step further by introducing artificially synthesised material into an organism.[13]

Plants, animals or microorganisms that have been changed through genetic engineering are termed genetically modified organisms or GMOs.[14] If genetic material from another species is added to the host, the resulting organism is called transgenic. If genetic material from the same species or a species that can naturally breed with the host is used the resulting organism is called cisgenic.[15] If genetic engineering is used to remove genetic material from the target organism the resulting organism is termed a knockout organism.[16] In Europe genetic modification is synonymous with genetic engineering while within the United States of America and Canada genetic modification can also be used to refer to more conventional breeding methods.[17][18][19]

History

[edit]Humans have altered the genomes of species for thousands of years through selective breeding, or artificial selection[20]: 1 [21]: 1 as contrasted with natural selection. More recently, mutation breeding has used exposure to chemicals or radiation to produce a high frequency of random mutations, for selective breeding purposes. Genetic engineering as the direct manipulation of DNA by humans outside breeding and mutations has only existed since the 1970s. The term "genetic engineering" was coined by the Russian-born geneticist Nikolay Timofeev-Ressovsky in his 1934 paper "The Experimental Production of Mutations", published in the British journal Biological Reviews.[22] Jack Williamson used the term in his science fiction novel Dragon's Island, published in 1951[23] – one year before DNA's role in heredity was confirmed by Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase,[24] and two years before James Watson and Francis Crick showed that the DNA molecule has a double-helix structure – though the general concept of direct genetic manipulation was explored in rudimentary form in Stanley G. Weinbaum's 1936 science fiction story Proteus Island.[25][26]

In 1972, Paul Berg created the first recombinant DNA molecules by combining DNA from the monkey virus SV40 with that of the lambda virus.[27] In 1973 Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen created the first transgenic organism by inserting antibiotic resistance genes into the plasmid of an Escherichia coli bacterium.[28][29] A year later Rudolf Jaenisch created a transgenic mouse by introducing foreign DNA into its embryo, making it the world's first transgenic animal[30] These achievements led to concerns in the scientific community about potential risks from genetic engineering, which were first discussed in depth at the Asilomar Conference in 1975. One of the main recommendations from this meeting was that government oversight of recombinant DNA research should be established until the technology was deemed safe.[31][32]

In 1976 Genentech, the first genetic engineering company, was founded by Herbert Boyer and Robert Swanson and a year later the company produced a human protein (somatostatin) in E. coli. Genentech announced the production of genetically engineered human insulin in 1978.[33] In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court in the Diamond v. Chakrabarty case ruled that genetically altered life could be patented.[34] The insulin produced by bacteria was approved for release by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1982.[35]

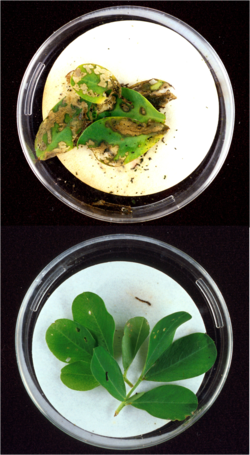

In 1983, a biotech company, Advanced Genetic Sciences (AGS) applied for U.S. government authorisation to perform field tests with the ice-minus strain of Pseudomonas syringae to protect crops from frost, but environmental groups and protestors delayed the field tests for four years with legal challenges.[36] In 1987, the ice-minus strain of P. syringae became the first genetically modified organism (GMO) to be released into the environment[37] when a strawberry field and a potato field in California were sprayed with it.[38] Both test fields were attacked by activist groups the night before the tests occurred: "The world's first trial site attracted the world's first field trasher".[37]

The first field trials of genetically engineered plants occurred in France and the US in 1986, tobacco plants were engineered to be resistant to herbicides.[39] The People's Republic of China was the first country to commercialise transgenic plants, introducing a virus-resistant tobacco in 1992.[40] In 1994 Calgene attained approval to commercially release the first genetically modified food, the Flavr Savr, a tomato engineered to have a longer shelf life.[41] In 1994, the European Union approved tobacco engineered to be resistant to the herbicide bromoxynil, making it the first genetically engineered crop commercialised in Europe.[42] In 1995, Bt potato was approved safe by the Environmental Protection Agency, after having been approved by the FDA, making it the first pesticide producing crop to be approved in the US.[43] In 2009 11 transgenic crops were grown commercially in 25 countries, the largest of which by area grown were the US, Brazil, Argentina, India, Canada, China, Paraguay and South Africa.[44]

In 2010, scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute created the first synthetic genome and inserted it into an empty bacterial cell. The resulting bacterium, named Mycoplasma laboratorium, could replicate and produce proteins.[45][46] Four years later this was taken a step further when a bacterium was developed that replicated a plasmid containing a unique base pair, creating the first organism engineered to use an expanded genetic alphabet.[47][48] In 2012, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier collaborated to develop the CRISPR/Cas9 system,[49][50] a technique which can be used to easily and specifically alter the genome of almost any organism.[51]

Process

[edit]

Creating a GMO is a multi-step process. Genetic engineers must first choose what gene they wish to insert into the organism. This is driven by what the aim is for the resultant organism and is built on earlier research. Genetic screens can be carried out to determine potential genes and further tests then used to identify the best candidates. The development of microarrays, transcriptomics and genome sequencing has made it much easier to find suitable genes.[52] Luck also plays its part; the Roundup Ready gene was discovered after scientists noticed a bacterium thriving in the presence of the herbicide.[53]

Gene isolation and cloning

[edit]The next step is to isolate the candidate gene. The cell containing the gene is opened and the DNA is purified.[54] The gene is separated by using restriction enzymes to cut the DNA into fragments[55] or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify up the gene segment.[56] These segments can then be extracted through gel electrophoresis. If the chosen gene or the donor organism's genome has been well studied it may already be accessible from a genetic library. If the DNA sequence is known, but no copies of the gene are available, it can also be artificially synthesised.[57] Once isolated the gene is ligated into a plasmid that is then inserted into a bacterium. The plasmid is replicated when the bacteria divide, ensuring unlimited copies of the gene are available.[58] The RK2 plasmid is notable for its ability to replicate in a wide variety of single-celled organisms, which makes it suitable as a genetic engineering tool.[59]

Before the gene is inserted into the target organism it must be combined with other genetic elements. These include a promoter and terminator region, which initiate and end transcription. A selectable marker gene is added, which in most cases confers antibiotic resistance, so researchers can easily determine which cells have been successfully transformed. The gene can also be modified at this stage for better expression or effectiveness. These manipulations are carried out using recombinant DNA techniques, such as restriction digests, ligations and molecular cloning.[60]

Inserting DNA into the host genome

[edit]

There are a number of techniques used to insert genetic material into the host genome. Some bacteria can naturally take up foreign DNA. This ability can be induced in other bacteria via stress (e.g. thermal or electric shock), which increases the cell membrane's permeability to DNA; up-taken DNA can either integrate with the genome or exist as extrachromosomal DNA. DNA is generally inserted into animal cells using microinjection, where it can be injected through the cell's nuclear envelope directly into the nucleus, or through the use of viral vectors.[61]

Plant genomes can be engineered by physical methods or by use of Agrobacterium for the delivery of sequences hosted in T-DNA binary vectors. In plants the DNA is often inserted using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation,[62] taking advantage of the Agrobacteriums T-DNA sequence that allows natural insertion of genetic material into plant cells.[63] Other methods include biolistics, where particles of gold or tungsten are coated with DNA and then shot into young plant cells,[64] and electroporation, which involves using an electric shock to make the cell membrane permeable to plasmid DNA.

As only a single cell is transformed with genetic material, the organism must be regenerated from that single cell. In plants this is accomplished through the use of tissue culture.[65][66] In animals it is necessary to ensure that the inserted DNA is present in the embryonic stem cells.[62] Bacteria consist of a single cell and reproduce clonally so regeneration is not necessary. Selectable markers are used to easily differentiate transformed from untransformed cells. These markers are usually present in the transgenic organism, although a number of strategies have been developed that can remove the selectable marker from the mature transgenic plant.[67]

Further testing using PCR, Southern hybridization, and DNA sequencing is conducted to confirm that an organism contains the new gene.[68] These tests can also confirm the chromosomal location and copy number of the inserted gene. The presence of the gene does not guarantee it will be expressed at appropriate levels in the target tissue so methods that look for and measure the gene products (RNA and protein) are also used. These include northern hybridisation, quantitative RT-PCR, Western blot, immunofluorescence, ELISA and phenotypic analysis.[69]

The new genetic material can be inserted randomly within the host genome or targeted to a specific location. The technique of gene targeting uses homologous recombination to make desired changes to a specific endogenous gene. This tends to occur at a relatively low frequency in plants and animals and generally requires the use of selectable markers. The frequency of gene targeting can be greatly enhanced through genome editing. Genome editing uses artificially engineered nucleases that create specific double-stranded breaks at desired locations in the genome, and use the cell's endogenous mechanisms to repair the induced break by the natural processes of homologous recombination and nonhomologous end-joining. There are four families of engineered nucleases: meganucleases,[70][71] zinc finger nucleases,[72][73] transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs),[74][75] and the Cas9-guideRNA system (adapted from CRISPR).[76][77] TALEN and CRISPR are the two most commonly used and each has its own advantages.[78] TALENs have greater target specificity, while CRISPR is easier to design and more efficient.[78] In addition to enhancing gene targeting, engineered nucleases can be used to introduce mutations at endogenous genes that generate a gene knockout.[79][80]

Applications

[edit]Genetic engineering has applications in medicine, research, industry and agriculture and can be used on a wide range of plants, animals and microorganisms. Bacteria, the first organisms to be genetically modified, can have plasmid DNA inserted containing new genes that code for medicines or enzymes that process food and other substrates.[81][82] Plants have been modified for insect protection, herbicide resistance, virus resistance, enhanced nutrition, tolerance to environmental pressures and the production of edible vaccines.[83] Most commercialised GMOs are insect resistant or herbicide tolerant crop plants.[84] Genetically modified animals have been used for research, model animals and the production of agricultural or pharmaceutical products. The genetically modified animals include animals with genes knocked out, increased susceptibility to disease, hormones for extra growth and the ability to express proteins in their milk.[85]

Medicine

[edit]Genetic engineering has many applications to medicine that include the manufacturing of drugs, creation of model animals that mimic human conditions and gene therapy. One of the earliest uses of genetic engineering was to mass-produce human insulin in bacteria.[33] This application has now been applied to human growth hormones, follicle stimulating hormones (for treating infertility), human albumin, monoclonal antibodies, antihemophilic factors, vaccines and many other drugs.[86][87] Mouse hybridomas, cells fused together to create monoclonal antibodies, have been adapted through genetic engineering to create human monoclonal antibodies.[88] Genetically engineered viruses are being developed that can still confer immunity, but lack the infectious sequences.[89]

Genetic engineering is also used to create animal models of human diseases. Genetically modified mice are the most common genetically engineered animal model.[90] They have been used to study and model cancer (the oncomouse), obesity, heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, substance abuse, anxiety, aging and Parkinson disease.[91] Potential cures can be tested against these mouse models.

Gene therapy is the genetic engineering of humans, generally by replacing defective genes with effective ones. Clinical research using somatic gene therapy has been conducted with several diseases, including X-linked SCID,[92] chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),[93][94] and Parkinson's disease.[95] In 2012, Alipogene tiparvovec became the first gene therapy treatment to be approved for clinical use.[96][97] In 2015 a virus was used to insert a healthy gene into the skin cells of a boy suffering from a rare skin disease, epidermolysis bullosa, in order to grow, and then graft healthy skin onto 80 percent of the boy's body which was affected by the illness.[98]

Germline gene therapy would result in any change being inheritable, which has raised concerns within the scientific community.[99][100] In 2015, CRISPR was used to edit the DNA of non-viable human embryos,[101][102] leading scientists of major world academies to call for a moratorium on inheritable human genome edits.[103] There are also concerns that the technology could be used not just for treatment, but for enhancement, modification or alteration of a human beings' appearance, adaptability, intelligence, character or behavior.[104] The distinction between cure and enhancement can also be difficult to establish.[105] In November 2018, He Jiankui announced that he had edited the genomes of two human embryos, to attempt to disable the CCR5 gene, which codes for a receptor that HIV uses to enter cells. The work was widely condemned as unethical, dangerous, and premature.[106] Currently, germline modification is banned in 40 countries. Scientists that do this type of research will often let embryos grow for a few days without allowing it to develop into a baby.[107]

Researchers are altering the genome of pigs to induce the growth of human organs, with the aim of increasing the success of pig to human organ transplantation.[108] Scientists are creating "gene drives", changing the genomes of mosquitoes to make them immune to malaria, and then looking to spread the genetically altered mosquitoes throughout the mosquito population in the hopes of eliminating the disease.[109]

Research

[edit]

Genetic engineering is an important tool for natural scientists, with the creation of transgenic organisms one of the most important tools for analysis of gene function.[110] Genes and other genetic information from a wide range of organisms can be inserted into bacteria for storage and modification, creating genetically modified bacteria in the process. Bacteria are cheap, easy to grow, clonal, multiply quickly, relatively easy to transform and can be stored at -80 °C almost indefinitely. Once a gene is isolated it can be stored inside the bacteria providing an unlimited supply for research.[111]

Organisms are genetically engineered to discover the functions of certain genes. This could be the effect on the phenotype of the organism, where the gene is expressed or what other genes it interacts with. These experiments generally involve loss of function, gain of function, tracking and expression.

- Loss of function experiments, such as in a gene knockout experiment, in which an organism is engineered to lack the activity of one or more genes. In a simple knockout a copy of the desired gene has been altered to make it non-functional. Embryonic stem cells incorporate the altered gene, which replaces the already present functional copy. These stem cells are injected into blastocysts, which are implanted into surrogate mothers. This allows the experimenter to analyse the defects caused by this mutation and thereby determine the role of particular genes. It is used especially frequently in developmental biology.[112] When this is done by creating a library of genes with point mutations at every position in the area of interest, or even every position in the whole gene, this is called "scanning mutagenesis". The simplest method, and the first to be used, is "alanine scanning", where every position in turn is mutated to the unreactive amino acid alanine.[113]

- Gain of function experiments, the logical counterpart of knockouts. These are sometimes performed in conjunction with knockout experiments to more finely establish the function of the desired gene. The process is much the same as that in knockout engineering, except that the construct is designed to increase the function of the gene, usually by providing extra copies of the gene or inducing synthesis of the protein more frequently. Gain of function is used to tell whether or not a protein is sufficient for a function, but does not always mean it is required, especially when dealing with genetic or functional redundancy.[112]

- Tracking experiments, which seek to gain information about the localisation and interaction of the desired protein. One way to do this is to replace the wild-type gene with a 'fusion' gene, which is a juxtaposition of the wild-type gene with a reporting element such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) that will allow easy visualisation of the products of the genetic modification. While this is a useful technique, the manipulation can destroy the function of the gene, creating secondary effects and possibly calling into question the results of the experiment. More sophisticated techniques are now in development that can track protein products without mitigating their function, such as the addition of small sequences that will serve as binding motifs to monoclonal antibodies.[112]

- Expression studies aim to discover where and when specific proteins are produced. In these experiments, the DNA sequence before the DNA that codes for a protein, known as a gene's promoter, is reintroduced into an organism with the protein coding region replaced by a reporter gene such as GFP or an enzyme that catalyses the production of a dye. Thus the time and place where a particular protein is produced can be observed. Expression studies can be taken a step further by altering the promoter to find which pieces are crucial for the proper expression of the gene and are actually bound by transcription factor proteins; this process is known as promoter bashing.[114]

Industrial

[edit]Organisms can have their cells transformed with a gene coding for a useful protein, such as an enzyme, so that they will overexpress the desired protein. Mass quantities of the protein can then be manufactured by growing the transformed organism in bioreactor equipment using industrial fermentation, and then purifying the protein.[115] Some genes do not work well in bacteria, so yeast, insect cells or mammalian cells can also be used.[116] These techniques are used to produce medicines such as insulin, human growth hormone, and vaccines, supplements such as tryptophan, aid in the production of food (chymosin in cheese making) and fuels.[117] Other applications with genetically engineered bacteria could involve making them perform tasks outside their natural cycle, such as making biofuels,[118] cleaning up oil spills, carbon and other toxic waste[119] and detecting arsenic in drinking water.[120] Certain genetically modified microbes can also be used in biomining and bioremediation, due to their ability to extract heavy metals from their environment and incorporate them into compounds that are more easily recoverable.[121]

In materials science, a genetically modified virus has been used in a research laboratory as a scaffold for assembling a more environmentally friendly lithium-ion battery.[122][123] Bacteria have also been engineered to function as sensors by expressing a fluorescent protein under certain environmental conditions.[124]

Agriculture

[edit]

One of the best-known and controversial applications of genetic engineering is the creation and use of genetically modified crops or genetically modified livestock to produce genetically modified food. Crops have been developed to increase production, increase tolerance to abiotic stresses, alter the composition of the food, or to produce novel products.[126]

The first crops to be released commercially on a large scale provided protection from insect pests or tolerance to herbicides. Fungal and virus resistant crops have also been developed or are in development.[127][128] This makes the insect and weed management of crops easier and can indirectly increase crop yield.[129][130] GM crops that directly improve yield by accelerating growth or making the plant more hardy (by improving salt, cold or drought tolerance) are also under development.[131] In 2016 Salmon have been genetically modified with growth hormones to reach normal adult size much faster.[132]

GMOs have been developed that modify the quality of produce by increasing the nutritional value or providing more industrially useful qualities or quantities.[131] The Amflora potato produces a more industrially useful blend of starches. Soybeans and canola have been genetically modified to produce more healthy oils.[133][134] The first commercialised GM food was a tomato that had delayed ripening, increasing its shelf life.[135]

Plants and animals have been engineered to produce materials they do not normally make. Pharming uses crops and animals as bioreactors to produce vaccines, drug intermediates, or the drugs themselves; the useful product is purified from the harvest and then used in the standard pharmaceutical production process.[136] Cows and goats have been engineered to express drugs and other proteins in their milk, and in 2009 the FDA approved a drug produced in goat milk.[137][138]

Other applications

[edit]Genetic engineering has potential applications in conservation and natural area management. Gene transfer through viral vectors has been proposed as a means of controlling invasive species as well as vaccinating threatened fauna from disease.[139] Transgenic trees have been suggested as a way to confer resistance to pathogens in wild populations.[140] With the increasing risks of maladaptation in organisms as a result of climate change and other perturbations, facilitated adaptation through gene tweaking could be one solution to reducing extinction risks.[141] Applications of genetic engineering in conservation are thus far mostly theoretical and have yet to be put into practice.

Genetic engineering is also being used to create microbial art.[142] Some bacteria have been genetically engineered to create black and white photographs.[143] Novelty items such as lavender-colored carnations,[144] blue roses,[145] and glowing fish,[146][147] have also been produced through genetic engineering.

Regulation

[edit]The regulation of genetic engineering concerns the approaches taken by governments to assess and manage the risks associated with the development and release of GMOs. The development of a regulatory framework began in 1975, at Asilomar, California.[148] The Asilomar meeting recommended a set of voluntary guidelines regarding the use of recombinant technology.[31] As the technology improved the US established a committee at the Office of Science and Technology,[149] which assigned regulatory approval of GM food to the USDA, FDA and EPA.[150] The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, an international treaty that governs the transfer, handling, and use of GMOs,[151] was adopted on 29 January 2000.[152] One hundred and fifty-seven countries are members of the Protocol, and many use it as a reference point for their own regulations.[153]

The legal and regulatory status of GM foods varies by country, with some nations banning or restricting them, and others permitting them with widely differing degrees of regulation.[154][155][156][157] Some countries allow the import of GM food with authorisation, but either do not allow its cultivation (Russia, Norway, Israel) or have provisions for cultivation even though no GM products are yet produced (Japan, South Korea). Most countries that do not allow GMO cultivation do permit research.[158] Some of the most marked differences occur between the US and Europe. The US policy focuses on the product (not the process), only looks at verifiable scientific risks and uses the concept of substantial equivalence.[159] The European Union by contrast has possibly the most stringent GMO regulations in the world.[160] All GMOs, along with irradiated food, are considered "new food" and subject to extensive, case-by-case, science-based food evaluation by the European Food Safety Authority. The criteria for authorisation fall in four broad categories: "safety", "freedom of choice", "labelling", and "traceability".[161] The level of regulation in other countries that cultivate GMOs lie in between Europe and the United States.

| Region | Regulators | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| US | USDA, FDA and EPA[150] | |

| Europe | European Food Safety Authority[161] | |

| Canada | Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency[162][163] | Regulated products with novel features regardless of method of origin[164][165] |

| Africa | Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa[166] | Final decision lies with each individual country.[166] |

| China | Office of Agricultural Genetic Engineering Biosafety Administration[167] | |

| India | Institutional Biosafety Committee, Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation and Genetic Engineering Approval Committee[168] | |

| Argentina | National Agricultural Biotechnology Advisory Committee (environmental impact), the National Service of Health and Agrifood Quality (food safety) and the National Agribusiness Direction (effect on trade)[169] | Final decision made by the Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock, Fishery and Food.[169] |

| Brazil | National Biosafety Technical Commission (environmental and food safety) and the Council of Ministers (commercial and economical issues)[169] | |

| Australia | Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (oversees all GM products), Therapeutic Goods Administration (GM medicines) and Food Standards Australia New Zealand (GM food).[170][171] | The individual state governments can then assess the impact of release on markets and trade and apply further legislation to control approved genetically modified products.[171] |

One of the key issues concerning regulators is whether GM products should be labeled. The European Commission says that mandatory labeling and traceability are needed to allow for informed choice, avoid potential false advertising[172] and facilitate the withdrawal of products if adverse effects on health or the environment are discovered.[173] The American Medical Association[174] and the American Association for the Advancement of Science[175] say that absent scientific evidence of harm even voluntary labeling is misleading and will falsely alarm consumers. Labeling of GMO products in the marketplace is required in 64 countries.[176] Labeling can be mandatory up to a threshold GM content level (which varies between countries) or voluntary. In Canada and the US labeling of GM food is voluntary,[177] while in Europe all food (including processed food) or feed which contains greater than 0.9% of approved GMOs must be labelled.[160]

Controversy

[edit]Critics have objected to the use of genetic engineering on several grounds, including ethical, ecological and economic concerns. Many of these concerns involve GM crops and whether food produced from them is safe and what impact growing them will have on the environment. These controversies have led to litigation, international trade disputes, and protests, and to restrictive regulation of commercial products in some countries.[178]

Accusations that scientists are "playing God" and other religious issues have been ascribed to the technology from the beginning.[179] Other ethical issues raised include the patenting of life,[180] the use of intellectual property rights,[181] the level of labeling on products,[182][183] control of the food supply[184] and the objectivity of the regulatory process.[185] Although doubts have been raised,[186] economically most studies have found growing GM crops to be beneficial to farmers.[187][188][189]

Gene flow between GM crops and compatible plants, along with increased use of selective herbicides, can increase the risk of "superweeds" developing.[190] Other environmental concerns involve potential impacts on non-target organisms, including soil microbes,[191] and an increase in secondary and resistant insect pests.[192][193] Many of the environmental impacts regarding GM crops may take many years to be understood and are also evident in conventional agriculture practices.[191][194] With the commercialisation of genetically modified fish there are concerns over what the environmental consequences will be if they escape.[195]

There are three main concerns over the safety of genetically modified food: whether they may provoke an allergic reaction; whether the genes could transfer from the food into human cells; and whether the genes not approved for human consumption could outcross to other crops.[196] There is a scientific consensus[197][198][199][200] that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food,[201][202][203][204][205] but that each GM food needs to be tested on a case-by-case basis before introduction.[206][207][208] Nonetheless, members of the public are less likely than scientists to perceive GM foods as safe.[209][210][211][212]

In popular culture

[edit]Genetic engineering features in many science fiction stories.[25] Frank Herbert's novel The White Plague describes the deliberate use of genetic engineering to create a pathogen which specifically kills women.[25] Another of Herbert's creations, the Dune series of novels, uses genetic engineering to create the powerful Tleilaxu.[213] Few films have informed audiences about genetic engineering, with the exception of the 1978 The Boys from Brazil and the 1993 Jurassic Park, both of which make use of a lesson, a demonstration, and a clip of scientific film.[214][215] Genetic engineering methods are weakly represented in film; Michael Clark, writing for the Wellcome Trust, calls the portrayal of genetic engineering and biotechnology "seriously distorted"[215] in films such as The 6th Day. In Clark's view, the biotechnology is typically "given fantastic but visually arresting forms" while the science is either relegated to the background or fictionalised to suit a young audience.[215]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Genetic Engineering". Genome.gov. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Terms and Acronyms". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency online. Archived from the original on 19 February 1999. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Vert M, Doi Y, Hellwich KH, Hess M, Hodge P, Kubisa P, Rinaudo M, Schué F (2012). "Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 84 (2): 377–410. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04. S2CID 98107080.

- ^ "How does GM differ from conventional plant breeding?". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Erwin E, Gendin S, Kleiman L (22 December 2015). Ethical Issues in Scientific Research: An Anthology. Routledge. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-134-81774-0.

- ^ Alexander DR (May 2003). "Uses and abuses of genetic engineering". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 79 (931): 249–51. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.931.249. PMC 1742694. PMID 12782769.

- ^ Nielsen J (1 July 2013). "Production of biopharmaceutical proteins by yeast: advances through metabolic engineering". Bioengineered. 4 (4): 207–11. doi:10.4161/bioe.22856. PMC 3728191. PMID 23147168.

- ^ Qaim M, Kouser S (5 June 2013). "Genetically modified crops and food security". PLOS ONE. 8 (6) e64879. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864879Q. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064879. PMC 3674000. PMID 23755155.

- ^ a b The European Parliament and the council of the European Union (12 March 2001). "Directive on the release of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) Directive 2001/18/EC ANNEX I A". Official Journal of the European Communities.

- ^ "Economic Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops on the Agri-Food Sector; p. 42 Glossary – Term and Definitions" (PDF). The European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013.

Genetic engineering: The manipulation of an organism's genetic endowment by introducing or eliminating specific genes through modern molecular biology techniques. A broad definition of genetic engineering also includes selective breeding and other means of artificial selection

- ^ Van Eenennaam A. "Is Livestock Cloning Another Form of Genetic Engineering?" (PDF). agbiotech. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

- ^ Suter DM, Dubois-Dauphin M, Krause KH (July 2006). "Genetic engineering of embryonic stem cells" (PDF). Swiss Medical Weekly. 136 (27–28): 413–5. doi:10.4414/smw.2006.11406. PMID 16897894. S2CID 4945176. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011.

- ^ Andrianantoandro E, Basu S, Karig DK, Weiss R (16 May 2006). "Synthetic biology: new engineering rules for an emerging discipline". Molecular Systems Biology. 2 (2006.0028): 2006.0028. doi:10.1038/msb4100073. PMC 1681505. PMID 16738572.

- ^ "What is genetic modification (GM)?". CSIRO.

- ^ Jacobsen E, Schouten HJ (2008). "Cisgenesis, a New Tool for Traditional Plant Breeding, Should be Exempted from the Regulation on Genetically Modified Organisms in a Step by Step Approach". Potato Research. 51: 75–88. doi:10.1007/s11540-008-9097-y. S2CID 38742532.

- ^ Capecchi MR (October 2001). "Generating mice with targeted mutations". Nature Medicine. 7 (10): 1086–90. doi:10.1038/nm1001-1086. PMID 11590420. S2CID 14710881.

- ^ Staff Biotechnology – Glossary of Agricultural Biotechnology Terms Archived 30 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine United States Department of Agriculture, "Genetic modification: The production of heritable improvements in plants or animals for specific uses, via either genetic engineering or other more traditional methods. Some countries other than the United States use this term to refer specifically to genetic engineering.", Retrieved 5 November 2012

- ^ Maryanski JH (19 October 1999). "Genetically Engineered Foods". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition at the Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009.

- ^ Staff (28 November 2005) Health Canada – The Regulation of Genetically Modified Food Archived 10 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine Glossary definition of Genetically Modified: "An organism, such as a plant, animal or bacterium, is considered genetically modified if its genetic material has been altered through any method, including conventional breeding. A 'GMO' is a genetically modified organism.", Retrieved 5 November 2012

- ^ Root C (2007). Domestication. Greenwood Publishing Groups.

- ^ Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss E (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of plants in the old world. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Timofeev-Ressovsky NW (October 1934). "The Experimental Production of Mutations". Biological Reviews. 9 (4): 411–457. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1934.tb01255.x. S2CID 86396986.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (2004). "Genetic Engineering". Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction Literature. Scarecrow Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8108-4938-9.

- ^ Hershey AD, Chase M (May 1952). "Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage". The Journal of General Physiology. 36 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1085/jgp.36.1.39. PMC 2147348. PMID 12981234.

- ^ a b c "Genetic Engineering". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Shiv Kant Prasad; Ajay Dash (2008). Modern Concepts in Nanotechnology, Volume 5. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8356-296-6.

- ^ Jackson DA, Symons RH, Berg P (October 1972). "Biochemical method for inserting new genetic information into DNA of Simian Virus 40: circular SV40 DNA molecules containing lambda phage genes and the galactose operon of Escherichia coli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 69 (10): 2904–9. Bibcode:1972PNAS...69.2904J. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.10.2904. PMC 389671. PMID 4342968.

- ^ Arnold P (2009). "History of Genetics: Genetic Engineering Timeline".

- ^ Gutschi S, Hermann W, Stenzl W, Tscheliessnigg KH (1 May 1973). "[Displacement of electrodes in pacemaker patients (author's transl)]". Zentralblatt für Chirurgie. 104 (2): 100–4. PMID 433482.

- ^ Jaenisch R, Mintz B (April 1974). "Simian virus 40 DNA sequences in DNA of healthy adult mice derived from preimplantation blastocysts injected with viral DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (4): 1250–4. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.1250J. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.4.1250. PMC 388203. PMID 4364530.

- ^ a b Berg P, Baltimore D, Brenner S, Roblin RO, Singer MF (June 1975). "Summary statement of the Asilomar conference on recombinant DNA molecules". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 72 (6): 1981–4. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.1981B. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.6.1981. PMC 432675. PMID 806076.

- ^ "NIH Guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules". Office of Biotechnology Activities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012.

- ^ a b Goeddel DV, Kleid DG, Bolivar F, Heyneker HL, Yansura DG, Crea R, Hirose T, Kraszewski A, Itakura K, Riggs AD (January 1979). "Expression in Escherichia coli of chemically synthesized genes for human insulin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 76 (1): 106–10. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76..106G. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.1.106. PMC 382885. PMID 85300.

- ^ US Supreme Court Cases from Justia & Oyez (16 June 1980). "Diamond V Chakrabarty". Justia. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Artificial Genes". Time. 15 November 1982. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Bratspies R (2007). "Some Thoughts on the American Approach to Regulating Genetically Modified Organisms". Kansas Journal of Law & Public Policy. 16 (3): 101–31. SSRN 1017832.

- ^ a b "GM crops: A bitter harvest?". 14 June 2002. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Maugh, Thomas H. II (9 June 1987). "Altered Bacterium Does Its Job: Frost Failed to Damage Sprayed Test Crop, Company Says". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ James C (1996). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995" (PDF). The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ James C (1997). "Global Status of Transgenic Crops in 1997" (PDF). ISAAA Briefs No. 5.: 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2009.

- ^ Bruening G, Lyons JM (2000). "The case of the FLAVR SAVR tomato". California Agriculture. 54 (4): 6–7. doi:10.3733/ca.v054n04p6 (inactive 12 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ MacKenzie D (18 June 1994). "Transgenic tobacco is European first". New Scientist.

- ^ "Lawrence Journal-World - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ "Executive Summary: Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2009 - ISAAA Brief 41-2009 | ISAAA.org". www.isaaa.org. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Pennisi E (May 2010). "Genomics. Synthetic genome brings new life to bacterium". Science. 328 (5981): 958–9. doi:10.1126/science.328.5981.958. PMID 20488994.

- ^ Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, et al. (July 2010). "Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome". Science. 329 (5987): 52–6. Bibcode:2010Sci...329...52G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.167.1455. doi:10.1126/science.1190719. PMID 20488990. S2CID 7320517.

- ^ Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Lavergne T, Chen T, Dai N, Foster JM, Corrêa IR, Romesberg FE (May 2014). "A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 385–8. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..385M. doi:10.1038/nature13314. PMC 4058825. PMID 24805238.

- ^ Thyer R, Ellefson J (May 2014). "Synthetic biology: New letters for life's alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 291–2. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..291T. doi:10.1038/nature13335. PMID 24805244. S2CID 4399670.

- ^ Pollack A (11 May 2015). "Jennifer Doudna, a Pioneer Who Helped Simplify Genome Editing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E (August 2012). "A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity". Science. 337 (6096): 816–21. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..816J. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. PMC 6286148. PMID 22745249.

- ^ Ledford H (March 2016). "CRISPR: gene editing is just the beginning". Nature. 531 (7593): 156–9. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..156L. doi:10.1038/531156a. PMID 26961639.

- ^ Koh HJ, Kwon SY, Thomson M (26 August 2015). Current Technologies in Plant Molecular Breeding: A Guide Book of Plant Molecular Breeding for Researchers. Springer. p. 242. ISBN 978-94-017-9996-6.

- ^ "How to Make a GMO". Science in the News. 9 August 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Nicholl, Desmond S.T. (29 May 2008). An Introduction to Genetic Engineering. Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-139-47178-7.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. (2002). "Isolating, Cloning, and Sequencing DNA". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ^ Kaufman RI, Nixon BT (July 1996). "Use of PCR to isolate genes encoding sigma54-dependent activators from diverse bacteria". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (13): 3967–70. doi:10.1128/jb.178.13.3967-3970.1996. PMC 232662. PMID 8682806.

- ^ Liang J, Luo Y, Zhao H (2011). "Synthetic biology: putting synthesis into biology". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 3 (1): 7–20. doi:10.1002/wsbm.104. PMC 3057768. PMID 21064036.

- ^ "5. The Process of Genetic Modification". www.fao.org. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ J M Blatny, T Brautaset, C H Winther-Larsen, K Haugan and S Valla: "Construction and use of a versatile set of broad-host-range cloning and expression vectors based on the RK2 replicon", Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, Volume 63, Issue 2, p. 370

- ^ Berg P, Mertz JE (January 2010). "Personal reflections on the origins and emergence of recombinant DNA technology". Genetics. 184 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.112144. PMC 2815933. PMID 20061565.

- ^ Chen I, Dubnau D (March 2004). "DNA uptake during bacterial transformation". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 2 (3): 241–9. doi:10.1038/nrmicro844. PMID 15083159. S2CID 205499369.

- ^ a b National Research Council (US) Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health (1 January 2004). Methods and Mechanisms for Genetic Manipulation of Plants, Animals, and Microorganisms. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ Gelvin SB (March 2003). "Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation: the biology behind the "gene-jockeying" tool". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 67 (1): 16–37, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.67.1.16-37.2003. PMC 150518. PMID 12626681.

- ^ Head G, Hull RH, Tzotzos GT (2009). Genetically Modified Plants: Assessing Safety and Managing Risk. London: Academic Pr. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-12-374106-6.

- ^ Tuomela M, Stanescu I, Krohn K (October 2005). "Validation overview of bio-analytical methods". Gene Therapy. 12 Suppl 1 (S1): S131-8. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302627. PMID 16231045. S2CID 23000818.

- ^ Narayanaswamy, S. (1994). Plant Cell and Tissue Culture. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. vi. ISBN 978-0-07-460277-5.

- ^ Hohn B, Levy AA, Puchta H (April 2001). "Elimination of selection markers from transgenic plants". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 12 (2): 139–43. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00188-9. PMID 11287227.

- ^ Setlow JK (31 October 2002). Genetic Engineering: Principles and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-306-47280-0.

- ^ Deepak S, Kottapalli K, Rakwal R, Oros G, Rangappa K, Iwahashi H, Masuo Y, Agrawal G (June 2007). "Real-Time PCR: Revolutionizing Detection and Expression Analysis of Genes". Current Genomics. 8 (4): 234–51. doi:10.2174/138920207781386960. PMC 2430684. PMID 18645596.

- ^ Grizot S, Smith J, Daboussi F, Prieto J, Redondo P, Merino N, Villate M, Thomas S, Lemaire L, Montoya G, Blanco FJ, Pâques F, Duchateau P (September 2009). "Efficient targeting of a SCID gene by an engineered single-chain homing endonuclease". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (16): 5405–19. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp548. PMC 2760784. PMID 19584299.

- ^ Gao H, Smith J, Yang M, Jones S, Djukanovic V, Nicholson MG, West A, Bidney D, Falco SC, Jantz D, Lyznik LA (January 2010). "Heritable targeted mutagenesis in maize using a designed endonuclease". The Plant Journal. 61 (1): 176–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04041.x. PMID 19811621.

- ^ Townsend JA, Wright DA, Winfrey RJ, Fu F, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Voytas DF (May 2009). "High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases". Nature. 459 (7245): 442–5. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..442T. doi:10.1038/nature07845. PMC 2743854. PMID 19404258.

- ^ Shukla VK, Doyon Y, Miller JC, DeKelver RC, Moehle EA, Worden SE, Mitchell JC, Arnold NL, Gopalan S, Meng X, Choi VM, Rock JM, Wu YY, Katibah GE, Zhifang G, McCaskill D, Simpson MA, Blakeslee B, Greenwalt SA, Butler HJ, Hinkley SJ, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD (May 2009). "Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases". Nature. 459 (7245): 437–41. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..437S. doi:10.1038/nature07992. PMID 19404259. S2CID 4323298.

- ^ Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF (October 2010). "Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases". Genetics. 186 (2): 757–61. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.120717. PMC 2942870. PMID 20660643.

- ^ Li T, Huang S, Jiang WZ, Wright D, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B (January 2011). "TAL nucleases (TALNs): hybrid proteins composed of TAL effectors and FokI DNA-cleavage domain". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (1): 359–72. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq704. PMC 3017587. PMID 20699274.

- ^ Esvelt KM, Wang HH (2013). "Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology". Molecular Systems Biology. 9: 641. doi:10.1038/msb.2012.66. PMC 3564264. PMID 23340847.

- ^ Tan WS, Carlson DF, Walton MW, Fahrenkrug SC, Hackett PB (2012). "Precision editing of large animal genomes". Advances in Genetics Volume 80. Vol. 80. pp. 37–97. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-404742-6.00002-8. ISBN 978-0-12-404742-6. PMC 3683964. PMID 23084873.

- ^ a b Malzahn A, Lowder L, Qi Y (24 April 2017). "Plant genome editing with TALEN and CRISPR". Cell & Bioscience. 7 21. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0148-4. PMC 5404292. PMID 28451378.

- ^ Ekker SC (2008). "Zinc finger-based knockout punches for zebrafish genes". Zebrafish. 5 (2): 121–3. doi:10.1089/zeb.2008.9988. PMC 2849655. PMID 18554175.

- ^ Geurts AM, Cost GJ, Freyvert Y, Zeitler B, Miller JC, Choi VM, Jenkins SS, Wood A, Cui X, Meng X, Vincent A, Lam S, Michalkiewicz M, Schilling R, Foeckler J, Kalloway S, Weiler H, Ménoret S, Anegon I, Davis GD, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Jacob HJ, Buelow R (July 2009). "Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases". Science. 325 (5939): 433. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..433G. doi:10.1126/science.1172447. PMC 2831805. PMID 19628861.

- ^ "Genetic Modification of Bacteria". Annenberg Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ Panesar, Pamit et al. (2010) "Enzymes in Food Processing: Fundamentals and Potential Applications", Chapter 10, I K International Publishing House, ISBN 978-93-80026-33-6

- ^ "GM traits list". International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications.

- ^ "ISAAA Brief 43-2011: Executive Summary". International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications.

- ^ Connor S (2 November 2007). "The mouse that shook the world". The Independent.

- ^ Avise JC (2004). The hope, hype & reality of genetic engineering: remarkable stories from agriculture, industry, medicine, and the environment. Oxford University Press US. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-516950-8.

- ^ "Engineering algae to make complex anti-cancer 'designer' drug". PhysOrg. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Roque AC, Lowe CR, Taipa MA (2004). "Antibodies and genetically engineered related molecules: production and purification". Biotechnology Progress. 20 (3): 639–54. doi:10.1021/bp030070k. PMID 15176864. S2CID 23142893.

- ^ Rodriguez LL, Grubman MJ (November 2009). "Foot and mouth disease virus vaccines". Vaccine. 27 (Suppl 4): D90-4. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.039. PMID 19837296.

- ^ "Background: Cloned and Genetically Modified Animals". Center for Genetics and Society. 14 April 2005. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Knockout Mice". Nation Human Genome Research Institute. 2009.

- ^ Fischer A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Cavazzana-Calvo M (June 2010). "20 years of gene therapy for SCID". Nature Immunology. 11 (6): 457–60. doi:10.1038/ni0610-457. PMID 20485269. S2CID 11300348.

- ^ Ledford H (2011). "Cell therapy fights leukaemia". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.472.

- ^ Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, Park J, Wang X, Cowell LG, et al. (March 2013). "CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Science Translational Medicine. 5 (177): 177ra38. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930. PMC 3742551. PMID 23515080.

- ^ LeWitt PA, Rezai AR, Leehey MA, Ojemann SG, Flaherty AW, Eskandar EN, et al. (April 2011). "AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial". The Lancet. Neurology. 10 (4): 309–19. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70039-4. PMID 21419704. S2CID 37154043.

- ^ "Gene therapy: Glybera approved by European Commission". BBC News. 2 November 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Richards S. "Gene Therapy Arrives in Europe". The Scientist. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Genetically Altered Skin Saves A Boy Dying of a Rare Disease". NPR.org. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "1990 The Declaration of Inuyama". 5 August 2001. Archived from the original on 5 August 2001.

- ^ Smith KR, Chan S, Harris J (October 2012). "Human germline genetic modification: scientific and bioethical perspectives". Archives of Medical Research. 43 (7): 491–513. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.09.003. PMID 23072719.

- ^ Kolata G (23 April 2015). "Chinese Scientists Edit Genes of Human Embryos, Raising Concerns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, et al. (May 2015). "CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes". Protein & Cell. 6 (5): 363–372. doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. PMC 4417674. PMID 25894090.

- ^ Wade N (3 December 2015). "Scientists Place Moratorium on Edits to Human Genome That Could Be Inherited". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Bergeson ER (1997). "The Ethics of Gene Therapy". Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Hanna KE. "Genetic Enhancement". National Human Genome Research Institute.

- ^ Begley S (28 November 2018). "Amid uproar, Chinese scientist defends creating gene-edited babies – STAT". STAT.

- ^ Li, Emily (31 July 2020). "Diagnostic Value of Spiral CT Chest Enhanced Scan". Journal of Clinical and Nursing Research.

- ^ "GM pigs best bet for organ transplant". Medical News Today. 21 September 2003. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Harmon A (26 November 2015). "Open Season Is Seen in Gene Editing of Animals". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Praitis V, Maduro MF (2011). "Transgenesis in C. elegans". Caenorhabditis elegans: Molecular Genetics and Development. Methods in Cell Biology. Vol. 106. pp. 161–85. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-544172-8.00006-2. ISBN 978-0-12-544172-8. PMID 22118277.

- ^ "Rediscovering Biology – Online Textbook: Unit 13 Genetically Modified Organisms". www.learner.org. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). "Studying Gene Expression and Function". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ^ Park SJ, Cochran JR (25 September 2009). Protein Engineering and Design. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-7659-2.

- ^ Kurnaz IA (8 May 2015). Techniques in Genetic Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-6090-8.

- ^ "Applications of Genetic Engineering". Microbiologyprocedure. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ "Biotech: What are transgenic organisms?". Easyscience. 2002. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Savage N (1 August 2007). "Making Gasoline from Bacteria: A biotech startup wants to coax fuels from engineered microbes". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Summers R (24 April 2013). "Bacteria churn out first ever petrol-like biofuel". New Scientist. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ "Applications of Some Genetically Engineered Bacteria". Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Sanderson K (24 February 2012). "New Portable Kit Detects Arsenic in Wells". Chemical and Engineering News. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB (2011). Campbell Biology Ninth Edition. San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-321-55823-7.

- ^ "New virus-built battery could power cars, electronic devices". Web.mit.edu. 2 April 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Hidden Ingredient in New, Greener Battery: A Virus". Npr.org. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "Researchers Synchronize Blinking 'Genetic Clocks' – Genetically Engineered Bacteria That Keep Track of Time". ScienceDaily. 24 January 2010.

- ^ Suszkiw J (November 1999). "Tifton, Georgia: A Peanut Pest Showdown". Agricultural Research. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ Magaña-Gómez JA, de la Barca AM (January 2009). "Risk assessment of genetically modified crops for nutrition and health". Nutrition Reviews. 67 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00130.x. PMID 19146501.

- ^ Islam A (2008). "Fungus Resistant Transgenic Plants: Strategies, Progress and Lessons Learnt". Plant Tissue Culture and Biotechnology. 16 (2): 117–38. doi:10.3329/ptcb.v16i2.1113.

- ^ "Disease resistant crops". GMO Compass. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010.

- ^ Demont M, Tollens E (2004). "First impact of biotechnology in the EU: Bt maize adoption in Spain". Annals of Applied Biology. 145 (2): 197–207. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2004.tb00376.x.

- ^ Chivian E, Bernstein A (2008). Sustaining Life. Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-19-517509-7.

- ^ a b Whitman DB (2000). "Genetically Modified Foods: Harmful or Helpful?". Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Pollack A (19 November 2015). "Genetically Engineered Salmon Approved for Consumption". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Rapeseed (canola) has been genetically engineered to modify its oil content with a gene encoding a "12:0 thioesterase" (TE) enzyme from the California bay plant (Umbellularia californica) to increase medium length fatty acids, see: Geo-pie.cornell.edu Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bomgardner MM (2012). "Replacing Trans Fat: New crops from Dow Chemical and DuPont target food makers looking for stable, heart-healthy oils". Chemical and Engineering News. 90 (11): 30–32. doi:10.1021/cen-09011-bus1.

- ^ Kramer MG, Redenbaugh K (1 January 1994). "Commercialization of a tomato with an antisense polygalacturonase gene: The FLAVR SAVR™ tomato story". Euphytica. 79 (3): 293–97. Bibcode:1994Euphy..79..293K. doi:10.1007/BF00022530. ISSN 0014-2336. S2CID 45071333.

- ^ Marvier M (2008). "Pharmaceutical crops in California, benefits and risks. A review" (PDF). Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 28 (1): 1–9. Bibcode:2008AgSD...28....1M. doi:10.1051/agro:2007050. S2CID 29538486. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2018.

- ^ "FDA Approves First Human Biologic Produced by GE Animals". US Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010.

- ^ Rebêlo P (15 July 2004). "GM cow milk 'could provide treatment for blood disease'". SciDev.

- ^ Angulo E, Cooke B (December 2002). "First synthesize new viruses then regulate their release? The case of the wild rabbit". Molecular Ecology. 11 (12): 2703–9. Bibcode:2002MolEc..11.2703A. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01635.x. hdl:10261/45541. PMID 12453252. S2CID 23916432.

- ^ Adams JM, Piovesan G, Strauss S, Brown S (2 August 2002). "The Case for Genetic Engineering of Native and Landscape Trees against Introduced Pests and Diseases". Conservation Biology. 16 (4): 874–79. Bibcode:2002ConBi..16..874A. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00523.x. S2CID 86697592.

- ^ Thomas MA, Roemer GW, Donlan CJ, Dickson BG, Matocq M, Malaney J (September 2013). "Ecology: Gene tweaking for conservation". Nature. 501 (7468): 485–6. doi:10.1038/501485a. PMID 24073449.

- ^ Pasko JM (4 March 2007). "Bio-artists bridge gap between arts, sciences: Use of living organisms is attracting attention and controversy". msnbc. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ Jackson J (6 December 2005). "Genetically Modified Bacteria Produce Living Photographs". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 16 December 2005.

- ^ "Plant gene replacement results in the world's only blue rose". phys.org. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Katsumoto Y, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Fukui Y, Brugliera F, Holton TA, Karan M, Nakamura N, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Togami J, Pigeaire A, Tao GQ, Nehra NS, Lu CY, Dyson BK, Tsuda S, Ashikari T, Kusumi T, Mason JG, Tanaka Y (November 2007). "Engineering of the rose flavonoid biosynthetic pathway successfully generated blue-hued flowers accumulating delphinidin". Plant & Cell Physiology. 48 (11): 1589–600. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.319.8365. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcm131. PMID 17925311.

- ^ "WIPO - Search International and National Patent Collections". patentscope.wipo.int. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Stewart CN (April 2006). "Go with the glow: fluorescent proteins to light transgenic organisms" (PDF). Trends in Biotechnology. 24 (4): 155–62. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.02.002. PMID 16488034. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Berg P, Baltimore D, Boyer HW, Cohen SN, Davis RW, Hogness DS, Nathans D, Roblin R, Watson JD, Weissman S, Zinder ND (July 1974). "Letter: Potential biohazards of recombinant DNA molecules" (PDF). Science. 185 (4148): 303. Bibcode:1974Sci...185..303B. doi:10.1126/science.185.4148.303. PMC 388511. PMID 4600381. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ McHughen A, Smyth S (January 2008). "US regulatory system for genetically modified [genetically modified organism (GMO), rDNA or transgenic] crop cultivars". Plant Biotechnology Journal. 6 (1): 2–12. Bibcode:2008PBioJ...6....2M. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00300.x. PMID 17956539.

- ^ a b U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy (June 1986). "Coordinated framework for regulation of biotechnology; announcement of policy; notice for public comment" (PDF). Federal Register. 51 (123). U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy: 23302–23350. PMID 11655807. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ Redick, T.P. (2007). "The Cartagena Protocol on biosafety: Precautionary priority in biotech crop approvals and containment of commodities shipments, 2007". Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy. 18: 51–116.

- ^ "About the Protocol". The Biosafety Clearing-House (BCH). 29 May 2012.

- ^ "AgBioForum 13(3): Implications of Import Regulations and Information Requirements under the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety for GM Commodities in Kenya". 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms. Library of Congress, March 2014 (LL File No. 2013-009894). Summary about a number of countries. via

- ^ Bashshur R (February 2013). "FDA and Regulation of GMOs". American Bar Association. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Sifferlin A (3 October 2015). "Over Half of E.U. Countries Are Opting Out of GMOs". Time.

- ^ Lynch D, Vogel D (5 April 2001). "The Regulation of GMOs in Europe and the United States: A Case-Study of Contemporary European Regulatory Politics". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms - Law Library of Congress". Library of Congress. 22 January 2017.

- ^ Marden, Emily (1 May 2003). "Risk and Regulation: U.S. Regulatory Policy on Genetically Modified Food and Agriculture". Boston College Law Review. 44 (3): 733.

- ^ a b Davison J (2010). "GM plants: Science, politics and EC regulations". Plant Science. 178 (2): 94–98. Bibcode:2010PlnSc.178...94D. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.12.005.

- ^ a b GMO Compass: The European Regulatory System. Archived 14 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Government of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (20 March 2015). "Information for the general public". www.inspection.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Forsberg, Cecil W. (23 April 2013). "Genetically Modified Foods". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Evans, Brent and Lupescu, Mihai (15 July 2012) Canada – Agricultural Biotechnology Annual – 2012 GAIN (Global Agricultural Information Network) report CA12029, United States Department of Agriculture, Foreifn Agricultural Service, Retrieved 5 November 2012

- ^ McHugen A (14 September 2000). "Chapter 1: Hors-d'oeuvres and entrees/What is genetic modification? What are GMOs?". Pandora's Picnic Basket. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850674-4.

- ^ a b "Editorial: Transgenic harvest". Nature. 467 (7316): 633–634. 2010. Bibcode:2010Natur.467R.633.. doi:10.1038/467633b. PMID 20930796.

- ^ "AgBioForum 5(4): Agricultural Biotechnology Development and Policy in China". 5 September 2003. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ "TNAU Agritech Portal :: Bio Technology". agritech.tnau.ac.in.

- ^ a b c "BASF presentation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011.

- ^ Agriculture – Department of Primary Industries Archived 29 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Welcome to the Office of the Gene Technology Regulator Website". Office of the Gene Technology Regulator. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 On Genetically Modified Food And Feed" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2014.

The labeling should include objective information to the effect that a food or feed consists of, contains or is produced from GMOs. Clear labeling, irrespective of the detectability of DNA or protein resulting from the genetic modification in the final product, meets the demands expressed in numerous surveys by a large majority of consumers, facilitates informed choice and precludes potential misleading of consumers as regards methods of manufacture or production.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 1830/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 concerning the traceability and labeling of genetically modified organisms and the traceability of food and feed products produced from genetically modified organisms and amending Directive 2001/18/EC". Official Journal L 268. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2003. pp. 24–28.

(3) Traceability requirements for GMOs should facilitate both the withdrawal of products where unforeseen adverse effects on human health, animal health or the environment, including ecosystems, are established, and the targeting of monitoring to examine potential effects on, in particular, the environment. Traceability should also facilitate the implementation of risk management measures in accordance with the precautionary principle. (4) Traceability requirements for food and feed produced from GMOs should be established to facilitate accurate labeling of such products.

- ^ "Report 2 of the Council on Science and Public Health: Labeling of Bioengineered Foods" (PDF). American Medical Association. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012.

- ^ American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Board of Directors (2012). Statement by the AAAS Board of Directors On Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods, and associated Press release: Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers Archived 4 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hallenbeck T (27 April 2014). "How GMO labeling came to pass in Vermont". Burlington Free Press. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ "The Regulation of Genetically Modified Foods". Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ Sheldon IM (1 March 2002). "Regulation of biotechnology: will we ever 'freely' trade GMOs?". European Review of Agricultural Economics. 29 (1): 155–76. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.7670. doi:10.1093/erae/29.1.155. ISSN 0165-1587.

- ^ Dabrock P (December 2009). "Playing God? Synthetic biology as a theological and ethical challenge". Systems and Synthetic Biology. 3 (1–4): 47–54. doi:10.1007/s11693-009-9028-5. PMC 2759421. PMID 19816799.

- ^ Brown C (October 2000). "Patenting life: genetically altered mice an invention, court declares". CMAJ. 163 (7): 867–8. PMC 80518. PMID 11033718.

- ^ Zhou W (10 August 2015). "The Patent Landscape of Genetically Modified Organisms". Science in the News. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Puckett L (20 April 2016). "Why The New GMO Food-Labeling Law Is So Controversial". Huffington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Miller H (12 April 2016). "GMO food labels are meaningless". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Savage S. "Who Controls The Food Supply?". Forbes. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Knight AJ (14 April 2016). Science, Risk, and Policy. Routledge. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-317-28081-1.

- ^ Hakim D (29 October 2016). "Doubts About the Promised Bounty of Genetically Modified Crops". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Areal FJ, Riesgo L, Rodríguez-Cerezo E (1 February 2013). "Economic and agronomic impact of commercialized GM crops: a meta-analysis". The Journal of Agricultural Science. 151 (1): 7–33. doi:10.1017/S0021859612000111. S2CID 85891950.

- ^ Finger R, El Benni N, Kaphengst T, Evans C, Herbert S, Lehmann B, Morse S, Stupak N (10 May 2011). "A Meta Analysis on Farm-Level Costs and Benefits of GM Crops" (PDF). Sustainability. 3 (5): 743–62. Bibcode:2011Sust....3..743F. doi:10.3390/su3050743. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2018.

- ^ Klümper W, Qaim M (3 November 2014). "A meta-analysis of the impacts of genetically modified crops". PLOS ONE. 9 (11) e111629. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1629K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111629. PMC 4218791. PMID 25365303.

- ^ Qiu J (2013). "Genetically modified crops pass benefits to weeds". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.13517. S2CID 87415065.

- ^ a b "GMOs and the environment". www.fao.org. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Dively GP, Venugopal PD, Finkenbinder C (30 December 2016). "Field-Evolved Resistance in Corn Earworm to Cry Proteins Expressed by Transgenic Sweet Corn". PLOS ONE. 11 (12) e0169115. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1169115D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169115. PMC 5201267. PMID 28036388.

- ^ Qiu, Jane (13 May 2010). "GM crop use makes minor pests major problem". Nature News. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.464.7885. doi:10.1038/news.2010.242.

- ^ Gilbert N (May 2013). "Case studies: A hard look at GM crops". Nature. 497 (7447): 24–6. Bibcode:2013Natur.497...24G. doi:10.1038/497024a. PMID 23636378. S2CID 4417399.

- ^ "Are GMO Fish Safe for the Environment? | Accumulating Glitches | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ "Q&A: genetically modified food". World Health Organization. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Nicolia A, Manzo A, Veronesi F, Rosellini D (March 2014). "An overview of the last 10 years of genetically engineered crop safety research". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 34 (1): 77–88. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.823595. PMID 24041244. S2CID 9836802.

We have reviewed the scientific literature on GE crop safety for the last 10 years that catches the scientific consensus matured since GE plants became widely cultivated worldwide, and we can conclude that the scientific research conducted so far has not detected any significant hazard directly connected with the use of GM crops. The literature about Biodiversity and the GE food/feed consumption has sometimes resulted in animated debate regarding the suitability of the experimental designs, the choice of the statistical methods or the public accessibility of data. Such debate, even if positive and part of the natural process of review by the scientific community, has frequently been distorted by the media and often used politically and inappropriately in anti-GE crops campaigns.

- ^ "State of Food and Agriculture 2003–2004. Agricultural Biotechnology: Meeting the Needs of the Poor. Health and environmental impacts of transgenic crops". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 8 February 2016.