Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Conserved sequence

View on Wikipedia

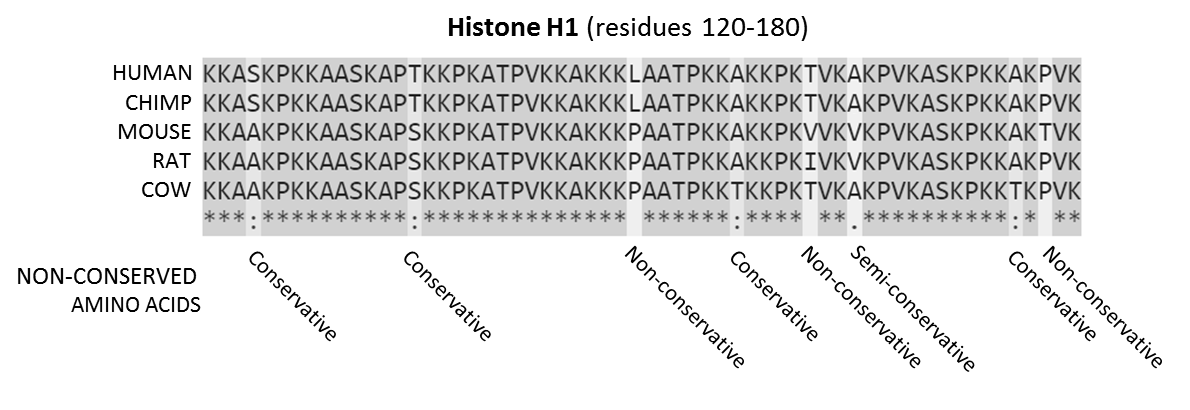

Sequences are the amino acids for residues 120-180 of the proteins. Residues that are conserved across all sequences are highlighted in grey. Below each site (i.e., position) of the protein sequence alignment is a key denoting conserved sites (*), sites with conservative replacements (:), sites with semi-conservative replacements (.), and sites with non-conservative replacements ( ).[1]

In evolutionary biology, conserved sequences are identical or similar sequences in nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) or proteins across species (orthologous sequences), or within a genome (paralogous sequences), or between donor and receptor taxa (xenologous sequences). Conservation indicates that a sequence has been maintained by natural selection.

A highly conserved sequence is one that has remained relatively unchanged far back up the phylogenetic tree, and hence far back in geological time. Examples of highly conserved sequences include the RNA components of ribosomes present in all domains of life, the homeobox sequences widespread amongst eukaryotes, and the tmRNA in bacteria. The study of sequence conservation overlaps with the fields of genomics, proteomics, evolutionary biology, phylogenetics, bioinformatics and mathematics.

History

[edit]The discovery of the role of DNA in heredity, and observations by Frederick Sanger of variation between animal insulins in 1949,[2] prompted early molecular biologists to study taxonomy from a molecular perspective.[3][4] Studies in the 1960s used DNA hybridization and protein cross-reactivity techniques to measure similarity between known orthologous proteins, such as hemoglobin[5] and cytochrome c.[6] In 1965, Émile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling introduced the concept of the molecular clock,[7] proposing that steady rates of amino acid replacement could be used to estimate the time since two organisms diverged. While initial phylogenies closely matched the fossil record, observations that some genes appeared to evolve at different rates led to the development of theories of molecular evolution.[3][4] Margaret Dayhoff's 1966 comparison of ferredoxin sequences showed that natural selection would act to conserve and optimise protein sequences essential to life.[8]

Mechanisms

[edit]Over many generations, nucleic acid sequences in the genome of an evolutionary lineage can gradually change over time due to random mutations and deletions.[9][10] Sequences may also recombine or be deleted due to chromosomal rearrangements. Conserved sequences are sequences which persist in the genome despite such forces, and have slower rates of mutation than the background mutation rate.[11]

Conservation can occur in coding and non-coding nucleic acid sequences. Highly conserved DNA sequences are thought to have functional value, although the role for many highly conserved non-coding DNA sequences is poorly understood.[12][13] The extent to which a sequence is conserved can be affected by varying selection pressures, its robustness to mutation, population size and genetic drift. Many functional sequences are also modular, containing regions which may be subject to independent selection pressures, such as protein domains.[14]

Coding sequence

[edit]In coding sequences, the nucleic acid and amino acid sequence may be conserved to different extents, as the degeneracy of the genetic code means that synonymous mutations in a coding sequence do not affect the amino acid sequence of its protein product.[15]

Amino acid sequences can be conserved to maintain the structure or function of a protein or domain. Conserved proteins undergo fewer amino acid replacements, or are more likely to substitute amino acids with similar biochemical properties.[16] Within a sequence, amino acids that are important for folding, structural stability, or that form a binding site may be more highly conserved.[17][18]

The nucleic acid sequence of a protein coding gene may also be conserved by other selective pressures. The codon usage bias in some organisms may restrict the types of synonymous mutations in a sequence. Nucleic acid sequences that cause secondary structure in the mRNA of a coding gene may be selected against, as some structures may negatively affect translation, or conserved where the mRNA also acts as a functional non-coding RNA.[19][20]

Non-coding

[edit]Non-coding sequences important for gene regulation, such as the binding or recognition sites of ribosomes and transcription factors, may be conserved within a genome. For example, the promoter of a conserved gene or operon may also be conserved. As with proteins, nucleic acids that are important for the structure and function of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) can also be conserved. However, sequence conservation in ncRNAs is generally poor compared to protein-coding sequences, and base pairs that contribute to structure or function are often conserved instead.[21][22]

Identification

[edit]Conserved sequences are typically identified by bioinformatics approaches based on sequence alignment. Advances in high-throughput DNA sequencing and protein mass spectrometry has substantially increased the availability of protein sequences and whole genomes for comparison since the early 2000s.[23][24]

Homology search

[edit]Conserved sequences may be identified by homology search, using tools such as BLAST, HMMER, OrthologR,[25] and Infernal.[26] Homology search tools may take an individual nucleic acid or protein sequence as input, or use statistical models generated from multiple sequence alignments of known related sequences. Statistical models such as profile-HMMs, and RNA covariance models which also incorporate structural information,[27] can be helpful when searching for more distantly related sequences. Input sequences are then aligned against a database of sequences from related individuals or other species. The resulting alignments are then scored based on the number of matching amino acids or bases, and the number of gaps or deletions generated by the alignment. Acceptable conservative substitutions may be identified using substitution matrices such as PAM and BLOSUM. Highly scoring alignments are assumed to be from homologous sequences. The conservation of a sequence may then be inferred by detection of highly similar homologs over a broad phylogenetic range.[28]

Multiple sequence alignment

[edit]

Multiple sequence alignments can be used to visualise conserved sequences. The CLUSTAL format includes a plain-text key to annotate conserved columns of the alignment, denoting conserved sequence (*), conservative mutations (:), semi-conservative mutations (.), and non-conservative mutations ( )[30] Sequence logos can also show conserved sequence by representing the proportions of characters at each point in the alignment by height.[29]

Genome alignment

[edit]

Whole genome alignments (WGAs) may also be used to identify highly conserved regions across species. Currently the accuracy and scalability of WGA tools remains limited due to the computational complexity of dealing with rearrangements, repeat regions and the large size of many eukaryotic genomes.[32] However, WGAs of 30 or more closely related bacteria (prokaryotes) are now increasingly feasible.[33][34]

Scoring systems

[edit]Other approaches use measurements of conservation based on statistical tests that attempt to identify sequences which mutate differently to an expected background (neutral) mutation rate.

The GERP (Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling) framework scores conservation of genetic sequences across species. This approach estimates the rate of neutral mutation in a set of species from a multiple sequence alignment, and then identifies regions of the sequence that exhibit fewer mutations than expected. These regions are then assigned scores based on the difference between the observed mutation rate and expected background mutation rate. A high GERP score then indicates a highly conserved sequence.[35][36]

LIST[37] [38] (Local Identity and Shared Taxa) is based on the assumption that variations observed in species closely related to human are more significant when assessing conservation compared to those in distantly related species. Thus, LIST utilizes the local alignment identity around each position to identify relevant sequences in the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and then it estimates conservation based on the taxonomy distances of these sequences to human. Unlike other tools, LIST ignores the count/frequency of variations in the MSA.

Aminode[39] combines multiple alignments with phylogenetic analysis to analyze changes in homologous proteins and produce a plot that indicates the local rates of evolutionary changes. This approach identifies the Evolutionarily Constrained Regions in a protein, which are segments that are subject to purifying selection and are typically critical for normal protein function.

Other approaches such as PhyloP and PhyloHMM incorporate statistical phylogenetics methods to compare probability distributions of substitution rates, which allows the detection of both conservation and accelerated mutation. First, a background probability distribution is generated of the number of substitutions expected to occur for a column in a multiple sequence alignment, based on a phylogenetic tree. The estimated evolutionary relationships between the species of interest are used to calculate the significance of any substitutions (i.e. a substitution between two closely related species may be less likely to occur than distantly related ones, and therefore more significant). To detect conservation, a probability distribution is calculated for a subset of the multiple sequence alignment, and compared to the background distribution using a statistical test such as a likelihood-ratio test or score test. P-values generated from comparing the two distributions are then used to identify conserved regions. PhyloHMM uses hidden Markov models to generate probability distributions. The PhyloP software package compares probability distributions using a likelihood-ratio test or score test, as well as using a GERP-like scoring system.[40][41][42]

Extreme conservation

[edit]Ultra-conserved elements

[edit]Ultra-conserved elements or UCEs are sequences that are highly similar or identical across multiple taxonomic groupings. These were first discovered in vertebrates,[43] and have subsequently been identified within widely-differing taxa.[44] While the origin and function of UCEs are poorly understood,[45] they have been used to investigate deep-time divergences in amniotes,[46] insects,[47] and between animals and plants.[48]

Universally conserved genes

[edit]The most highly conserved genes are those that can be found in all organisms. These consist mainly of the ncRNAs and proteins required for transcription and translation, which are assumed to have been conserved from the last universal common ancestor of all life.[49]

Genes or gene families that have been found to be universally conserved include GTP-binding elongation factors, Methionine aminopeptidase 2, Serine hydroxymethyltransferase, and ATP transporters.[50] Components of the transcription machinery, such as RNA polymerase and helicases, and of the translation machinery, such as ribosomal RNAs, tRNAs and ribosomal proteins are also universally conserved.[51]

Applications

[edit]Phylogenetics and taxonomy

[edit]Sets of conserved sequences are often used for generating phylogenetic trees, as it can be assumed that organisms with similar sequences are closely related.[52] The choice of sequences may vary depending on the taxonomic scope of the study. For example, the most highly conserved genes such as the 16S RNA and other ribosomal sequences are useful for reconstructing deep phylogenetic relationships and identifying bacterial phyla in metagenomics studies.[53][54] Sequences that are conserved within a clade but undergo some mutations, such as housekeeping genes, can be used to study species relationships.[55][56][57] The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, which is required for spacing conserved rRNA genes but undergoes rapid evolution, is commonly used to classify fungi and strains of rapidly evolving bacteria.[58][59][60][61]

Medical research

[edit]As highly conserved sequences often have important biological functions, they can be useful a starting point for identifying the cause of genetic diseases. Many congenital metabolic disorders and Lysosomal storage diseases are the result of changes to individual conserved genes, resulting in missing or faulty enzymes that are the underlying cause of the symptoms of the disease. Genetic diseases may be predicted by identifying sequences that are conserved between humans and lab organisms such as mice[62] or fruit flies,[63] and studying the effects of knock-outs of these genes.[64] Genome-wide association studies can also be used to identify variation in conserved sequences associated with disease or health outcomes. More than two dozen novel potential susceptibility loci have been discovered for Alzehimer's disease.[65][66]

Functional annotation

[edit]Identifying conserved sequences can be used to discover and predict functional sequences such as genes.[67] Conserved sequences with a known function, such as protein domains, can also be used to predict the function of a sequence. Databases of conserved protein domains such as Pfam and the Conserved Domain Database can be used to annotate functional domains in predicted protein coding genes.[68]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Clustal FAQ #Symbols". Clustal. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ Sanger, F. (24 September 1949). "Species Differences in Insulins". Nature. 164 (4169): 529. Bibcode:1949Natur.164..529S. doi:10.1038/164529a0. PMID 18141620. S2CID 4067991.

- ^ a b Marmur, J; Falkow, S; Mandel, M (October 1963). "New Approaches to Bacterial Taxonomy". Annual Review of Microbiology. 17 (1): 329–372. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.17.100163.001553. PMID 14147455.

- ^ a b Pace, N. R.; Sapp, J.; Goldenfeld, N. (17 January 2012). "Phylogeny and beyond: Scientific, historical, and conceptual significance of the first tree of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (4): 1011–1018. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.1011P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109716109. PMC 3268332. PMID 22308526.

- ^ Zuckerlandl, Emile; Pauling, Linus B. (1962). "Molecular disease, evolution, and genetic heterogeneity". Horizons in Biochemistry: 189–225.

- ^ Margoliash, E (October 1963). "Primary Structure and Evolution of Cytochrome C". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 50 (4): 672–679. Bibcode:1963PNAS...50..672M. doi:10.1073/pnas.50.4.672. PMC 221244. PMID 14077496.

- ^ Zuckerkandl, E; Pauling, LB (1965). "Evolutionary Divergence and Convergence in Proteins". Evolving Genes and And Proteins: 96–166. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4832-2734-4.50017-6. ISBN 978-1-4832-2734-4.

- ^ Eck, R. V.; Dayhoff, M. O. (15 April 1966). "Evolution of the Structure of Ferredoxin Based on Living Relics of Primitive Amino Acid Sequences". Science. 152 (3720): 363–366. Bibcode:1966Sci...152..363E. doi:10.1126/science.152.3720.363. PMID 17775169. S2CID 23208558.

- ^ Kimura, M (17 February 1968). "Evolutionary Rate at the Molecular Level". Nature. 217 (5129): 624–626. Bibcode:1968Natur.217..624K. doi:10.1038/217624a0. PMID 5637732. S2CID 4161261.

- ^ King, J. L.; Jukes, T. H. (16 May 1969). "Non-Darwinian Evolution". Science. 164 (3881): 788–798. Bibcode:1969Sci...164..788L. doi:10.1126/science.164.3881.788. PMID 5767777.

- ^ Kimura, M; Ohta, T (1974). "On Some Principles Governing Molecular Evolution". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 71 (7): 2848–2852. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.2848K. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.7.2848. PMC 388569. PMID 4527913.

- ^ Asthana, Saurabh; Roytberg, Mikhail; Stamatoyannopoulos, John; Sunyaev, Shamil (28 December 2007). Brudno, Michael (ed.). "Analysis of Sequence Conservation at Nucleotide Resolution". PLOS Computational Biology. 3 (12) e254. Bibcode:2007PLSCB...3..254A. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030254. ISSN 1553-7358. PMC 2230682. PMID 18166073.

- ^ Cooper, G. M.; Brown, C. D. (1 February 2008). "Qualifying the relationship between sequence conservation and molecular function". Genome Research. 18 (2): 201–205. doi:10.1101/gr.7205808. ISSN 1088-9051. PMID 18245453.

- ^ Gilson, Amy I.; Marshall-Christensen, Ahmee; Choi, Jeong-Mo; Shakhnovich, Eugene I. (2017). "The Role of Evolutionary Selection in the Dynamics of Protein Structure Evolution". Biophysical Journal. 112 (7): 1350–1365. arXiv:1606.05802. Bibcode:2017BpJ...112.1350G. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.029. PMC 5390048. PMID 28402878.

- ^ Hunt, Ryan C.; Simhadri, Vijaya L.; Iandoli, Matthew; Sauna, Zuben E.; Kimchi-Sarfaty, Chava (2014). "Exposing synonymous mutations". Trends in Genetics. 30 (7): 308–321. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2014.04.006. PMID 24954581.

- ^ Zhang, Jianzhi (2000). "Rates of Conservative and Radical Nonsynonymous Nucleotide Substitutions in Mammalian Nuclear Genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 50 (1): 56–68. Bibcode:2000JMolE..50...56Z. doi:10.1007/s002399910007. ISSN 0022-2844. PMID 10654260. S2CID 15248867.

- ^ Sousounis, Konstantinos; Haney, Carl E; Cao, Jin; Sunchu, Bharath; Tsonis, Panagiotis A (2012). "Conservation of the three-dimensional structure in non-homologous or unrelated proteins". Human Genomics. 6 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1479-7364-6-10. ISSN 1479-7364. PMC 3500211. PMID 23244440.

- ^ Kairys, Visvaldas; Fernandes, Miguel X. (2007). "SitCon: Binding site residue conservation visualization and protein sequence-to-function tool". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 107 (11): 2100–2110. Bibcode:2007IJQC..107.2100K. doi:10.1002/qua.21396. hdl:10400.13/5004. ISSN 0020-7608.

- ^ Chamary, JV; Hurst, Laurence D (2005). "Evidence for selection on synonymous mutations affecting stability of mRNA secondary structure in mammals". Genome Biology. 6 (9): R75. doi:10.1186/gb-2005-6-9-r75. PMC 1242210. PMID 16168082.

- ^ Wadler, C. S.; Vanderpool, C. K. (27 November 2007). "A dual function for a bacterial small RNA: SgrS performs base pairing-dependent regulation and encodes a functional polypeptide". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (51): 20454–20459. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10420454W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708102104. PMC 2154452. PMID 18042713.

- ^ Johnsson, Per; Lipovich, Leonard; Grandér, Dan; Morris, Kevin V. (March 2014). "Evolutionary conservation of long non-coding RNAs; sequence, structure, function". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1840 (3): 1063–1071. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.10.035. PMC 3909678. PMID 24184936.

- ^ Freyhult, E. K.; Bollback, J. P.; Gardner, P. P. (6 December 2006). "Exploring genomic dark matter: A critical assessment of the performance of homology search methods on noncoding RNA". Genome Research. 17 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1101/gr.5890907. PMC 1716261. PMID 17151342.

- ^ Margulies, E. H. (1 December 2003). "Identification and Characterization of Multi-Species Conserved Sequences". Genome Research. 13 (12): 2507–2518. doi:10.1101/gr.1602203. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 403793. PMID 14656959.

- ^ Edwards, John R.; Ruparel, Hameer; Ju, Jingyue (2005). "Mass-spectrometry DNA sequencing". Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 573 (1–2): 3–12. Bibcode:2005MRFMM.573....3E. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.07.021. PMID 15829234.

- ^ Drost, Hajk-Georg; Gabel, Alexander; Grosse, Ivo; Quint, Marcel (1 May 2015). "Evidence for Active Maintenance of Phylotranscriptomic Hourglass Patterns in Animal and Plant Embryogenesis". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (5): 1221–1231. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv012. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 4408408. PMID 25631928.

- ^ Nawrocki, E. P.; Eddy, S. R. (4 September 2013). "Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches". Bioinformatics. 29 (22): 2933–2935. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509. PMC 3810854. PMID 24008419.

- ^ Eddy, SR; Durbin, R (11 June 1994). "RNA sequence analysis using covariance models". Nucleic Acids Research. 22 (11): 2079–88. doi:10.1093/nar/22.11.2079. PMC 308124. PMID 8029015.

- ^ Trivedi, Rakesh; Nagarajaram, Hampapathalu Adimurthy (2020). "Substitution scoring matrices for proteins - An overview". Protein Science. 29 (11): 2150–2163. doi:10.1002/pro.3954. ISSN 0961-8368. PMC 7586916. PMID 32954566.

- ^ a b "Weblogo". UC Berkeley. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Clustal FAQ #Symbols". Clustal. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ "ECR Browser". ECR Browser. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Earl, Dent; Nguyen, Ngan; Hickey, Glenn; Harris, Robert S.; Fitzgerald, Stephen; Beal, Kathryn; Seledtsov, Igor; Molodtsov, Vladimir; Raney, Brian J.; Clawson, Hiram; Kim, Jaebum; Kemena, Carsten; Chang, Jia-Ming; Erb, Ionas; Poliakov, Alexander; Hou, Minmei; Herrero, Javier; Kent, William James; Solovyev, Victor; Darling, Aaron E.; Ma, Jian; Notredame, Cedric; Brudno, Michael; Dubchak, Inna; Haussler, David; Paten, Benedict (December 2014). "Alignathon: a competitive assessment of whole-genome alignment methods". Genome Research. 24 (12): 2077–2089. doi:10.1101/gr.174920.114. PMC 4248324. PMID 25273068.

- ^ Rouli, L.; Merhej, V.; Fournier, P.-E.; Raoult, D. (September 2015). "The bacterial pangenome as a new tool for analysing pathogenic bacteria". New Microbes and New Infections. 7: 72–85. doi:10.1016/j.nmni.2015.06.005. PMC 4552756. PMID 26442149.

- ^ Méric, Guillaume; Yahara, Koji; Mageiros, Leonardos; Pascoe, Ben; Maiden, Martin C. J.; Jolley, Keith A.; Sheppard, Samuel K.; Bereswill, Stefan (27 March 2014). "A Reference Pan-Genome Approach to Comparative Bacterial Genomics: Identification of Novel Epidemiological Markers in Pathogenic Campylobacter". PLOS ONE. 9 (3) e92798. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...992798M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092798. PMC 3968026. PMID 24676150.

- ^ Cooper, G. M. (17 June 2005). "Distribution and intensity of constraint in mammalian genomic sequence". Genome Research. 15 (7): 901–913. doi:10.1101/gr.3577405. PMC 1172034. PMID 15965027.

- ^ "Sidow Lab - GERP". Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Nawar Malhis; Steven J. M. Jones; Jörg Gsponer (2019). "Improved measures for evolutionary conservation that exploit taxonomy distances". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1556. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1556M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09583-2. PMC 6450959. PMID 30952844.

- ^ Nawar Malhis; Matthew Jacobson; Steven J. M. Jones; Jörg Gsponer (2020). "LIST-S2: Taxonomy Based Sorting of Deleterious Missense Mutations Across Species". Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (W1): W154 – W161. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa288. PMC 7319545. PMID 32352516.

- ^ Chang KT, Guo J, di Ronza A, Sardiello M (January 2018). "Aminode: Identification of Evolutionary Constraints in the Human Proteome". Sci. Rep. 8 (1): 1357. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.1357C. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-19744-w. PMC 5778061. PMID 29358731.

- ^ Pollard, K. S.; Hubisz, M. J.; Rosenbloom, K. R.; Siepel, A. (26 October 2009). "Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies". Genome Research. 20 (1): 110–121. doi:10.1101/gr.097857.109. PMC 2798823. PMID 19858363.

- ^ "PHAST: Home".

- ^ Fan, Xiaodan; Zhu, Jun; Schadt, Eric E; Liu, Jun S (2007). "Statistical power of phylo-HMM for evolutionarily conserved element detection". BMC Bioinformatics. 8 (1): 374. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-374. PMC 2194792. PMID 17919331.

- ^ Bejerano, G. (28 May 2004). "Ultraconserved Elements in the Human Genome". Science. 304 (5675): 1321–1325. Bibcode:2004Sci...304.1321B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.380.9305. doi:10.1126/science.1098119. PMID 15131266. S2CID 2790337.

- ^ Siepel, A. (1 August 2005). "Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes". Genome Research. 15 (8): 1034–1050. doi:10.1101/gr.3715005. PMC 1182216. PMID 16024819.

- ^ Harmston, N.; Baresic, A.; Lenhard, B. (11 November 2013). "The mystery of extreme non-coding conservation". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 368 (1632) 20130021. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0021. PMC 3826495. PMID 24218634.

- ^ Faircloth, B. C.; McCormack, J. E.; Crawford, N. G.; Harvey, M. G.; Brumfield, R. T.; Glenn, T. C. (9 January 2012). "Ultraconserved Elements Anchor Thousands of Genetic Markers Spanning Multiple Evolutionary Timescales". Systematic Biology. 61 (5): 717–726. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys004. PMID 22232343.

- ^ Faircloth, Brant C.; Branstetter, Michael G.; White, Noor D.; Brady, Seán G. (May 2015). "Target enrichment of ultraconserved elements from arthropods provides a genomic perspective on relationships among Hymenoptera". Molecular Ecology Resources. 15 (3): 489–501. arXiv:1406.0413. Bibcode:2015MolER..15..489F. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.12328. PMC 4407909. PMID 25207863.

- ^ Reneker, J.; Lyons, E.; Conant, G. C.; Pires, J. C.; Freeling, M.; Shyu, C.-R.; Korkin, D. (10 April 2012). "Long identical multispecies elements in plant and animal genomes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (19): E1183 – E1191. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121356109. PMC 3358895. PMID 22496592.

- ^ Isenbarger, Thomas A.; Carr, Christopher E.; Johnson, Sarah Stewart; Finney, Michael; Church, George M.; Gilbert, Walter; Zuber, Maria T.; Ruvkun, Gary (14 October 2008). "The Most Conserved Genome Segments for Life Detection on Earth and Other Planets". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 38 (6): 517–533. Bibcode:2008OLEB...38..517I. doi:10.1007/s11084-008-9148-z. PMID 18853276. S2CID 15707806.

- ^ Harris, J. K. (12 February 2003). "The Genetic Core of the Universal Ancestor". Genome Research. 13 (3): 407–412. doi:10.1101/gr.652803. PMC 430263. PMID 12618371.

- ^ Ban, Nenad; Beckmann, Roland; Cate, Jamie HD; Dinman, Jonathan D; Dragon, François; Ellis, Steven R; Lafontaine, Denis LJ; Lindahl, Lasse; Liljas, Anders; Lipton, Jeffrey M; McAlear, Michael A; Moore, Peter B; Noller, Harry F; Ortega, Joaquin; Panse, Vikram Govind; Ramakrishnan, V; Spahn, Christian MT; Steitz, Thomas A; Tchorzewski, Marek; Tollervey, David; Warren, Alan J; Williamson, James R; Wilson, Daniel; Yonath, Ada; Yusupov, Marat (February 2014). "A new system for naming ribosomal proteins". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 24: 165–169. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2014.01.002. PMC 4358319. PMID 24524803.

- ^ Gadagkar, Sudhindra R.; Rosenberg, Michael S.; Kumar, Sudhir (15 January 2005). "Inferring species phylogenies from multiple genes: Concatenated sequence tree versus consensus gene tree". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 304B (1): 64–74. Bibcode:2005JEZB..304...64G. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21026. PMID 15593277.

- ^ Ludwig, W; Schleifer, KH (October 1994). "Bacterial phylogeny based on 16S and 23S rRNA sequence analysis". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 15 (2–3): 155–73. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00132.x. PMID 7524576.

- ^ Hug, Laura A.; Baker, Brett J.; Anantharaman, Karthik; Brown, Christopher T.; Probst, Alexander J.; Castelle, Cindy J.; Butterfield, Cristina N.; Hernsdorf, Alex W.; Amano, Yuki; Ise, Kotaro; Suzuki, Yohey; Dudek, Natasha; Relman, David A.; Finstad, Kari M.; Amundson, Ronald; Thomas, Brian C.; Banfield, Jillian F. (11 April 2016). "A new view of the tree of life". Nature Microbiology. 1 (5): 16048. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.48. PMID 27572647.

- ^ Zhang, Liqing; Li, Wen-Hsiung (February 2004). "Mammalian Housekeeping Genes Evolve More Slowly than Tissue-Specific Genes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (2): 236–239. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh010. PMID 14595094.

- ^ Clermont, O.; Bonacorsi, S.; Bingen, E. (1 October 2000). "Rapid and Simple Determination of the Escherichia coli Phylogenetic Group". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 66 (10): 4555–4558. Bibcode:2000ApEnM..66.4555C. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000. PMC 92342. PMID 11010916.

- ^ Kullberg, Morgan; Nilsson, Maria A.; Arnason, Ulfur; Harley, Eric H.; Janke, Axel (August 2006). "Housekeeping Genes for Phylogenetic Analysis of Eutherian Relationships". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (8): 1493–1503. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl027. PMID 16751257.

- ^ Schoch, C. L.; Seifert, K. A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J. L.; Levesque, C. A.; Chen, W.; Bolchacova, E.; Voigt, K.; Crous, P. W.; Miller, A. N.; Wingfield, M. J.; Aime, M. C.; An, K.-D.; Bai, F.-Y.; Barreto, R. W.; Begerow, D.; Bergeron, M.-J.; Blackwell, M.; Boekhout, T.; Bogale, M.; Boonyuen, N.; Burgaz, A. R.; Buyck, B.; Cai, L.; Cai, Q.; Cardinali, G.; Chaverri, P.; Coppins, B. J.; Crespo, A.; Cubas, P.; Cummings, C.; Damm, U.; de Beer, Z. W.; de Hoog, G. S.; Del-Prado, R.; Dentinger, B.; Dieguez-Uribeondo, J.; Divakar, P. K.; Douglas, B.; Duenas, M.; Duong, T. A.; Eberhardt, U.; Edwards, J. E.; Elshahed, M. S.; Fliegerova, K.; Furtado, M.; Garcia, M. A.; Ge, Z.-W.; Griffith, G. W.; Griffiths, K.; Groenewald, J. Z.; Groenewald, M.; Grube, M.; Gryzenhout, M.; Guo, L.-D.; Hagen, F.; Hambleton, S.; Hamelin, R. C.; Hansen, K.; Harrold, P.; Heller, G.; Herrera, C.; Hirayama, K.; Hirooka, Y.; Ho, H.-M.; Hoffmann, K.; Hofstetter, V.; Hognabba, F.; Hollingsworth, P. M.; Hong, S.-B.; Hosaka, K.; Houbraken, J.; Hughes, K.; Huhtinen, S.; Hyde, K. D.; James, T.; Johnson, E. M.; Johnson, J. E.; Johnston, P. R.; Jones, E. B. G.; Kelly, L. J.; Kirk, P. M.; Knapp, D. G.; Koljalg, U.; Kovacs, G. M.; Kurtzman, C. P.; Landvik, S.; Leavitt, S. D.; Liggenstoffer, A. S.; Liimatainen, K.; Lombard, L.; Luangsa-ard, J. J.; Lumbsch, H. T.; Maganti, H.; Maharachchikumbura, S. S. N.; Martin, M. P.; May, T. W.; McTaggart, A. R.; Methven, A. S.; Meyer, W.; Moncalvo, J.-M.; Mongkolsamrit, S.; Nagy, L. G.; Nilsson, R. H.; Niskanen, T.; Nyilasi, I.; Okada, G.; Okane, I.; Olariaga, I.; Otte, J.; Papp, T.; Park, D.; Petkovits, T.; Pino-Bodas, R.; Quaedvlieg, W.; Raja, H. A.; Redecker, D.; Rintoul, T. L.; Ruibal, C.; Sarmiento-Ramirez, J. M.; Schmitt, I.; Schussler, A.; Shearer, C.; Sotome, K.; Stefani, F. O. P.; Stenroos, S.; Stielow, B.; Stockinger, H.; Suetrong, S.; Suh, S.-O.; Sung, G.-H.; Suzuki, M.; Tanaka, K.; Tedersoo, L.; Telleria, M. T.; Tretter, E.; Untereiner, W. A.; Urbina, H.; Vagvolgyi, C.; Vialle, A.; Vu, T. D.; Walther, G.; Wang, Q.-M.; Wang, Y.; Weir, B. S.; Weiss, M.; White, M. M.; Xu, J.; Yahr, R.; Yang, Z. L.; Yurkov, A.; Zamora, J.-C.; Zhang, N.; Zhuang, W.-Y.; Schindel, D. (27 March 2012). "Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (16): 6241–6246. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117018109. PMC 3341068. PMID 22454494.

- ^ Man, S. M.; Kaakoush, N. O.; Octavia, S.; Mitchell, H. (26 March 2010). "The Internal Transcribed Spacer Region, a New Tool for Use in Species Differentiation and Delineation of Systematic Relationships within the Campylobacter Genus". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 76 (10): 3071–3081. Bibcode:2010ApEnM..76.3071M. doi:10.1128/AEM.02551-09. PMC 2869123. PMID 20348308.

- ^ Ranjard, L.; Poly, F.; Lata, J.-C.; Mougel, C.; Thioulouse, J.; Nazaret, S. (1 October 2001). "Characterization of Bacterial and Fungal Soil Communities by Automated Ribosomal Intergenic Spacer Analysis Fingerprints: Biological and Methodological Variability". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 67 (10): 4479–4487. Bibcode:2001ApEnM..67.4479R. doi:10.1128/AEM.67.10.4479-4487.2001. PMC 93193. PMID 11571146.

- ^ Bidet, Philippe; Barbut, Frédéric; Lalande, Valérie; Burghoffer, Béatrice; Petit, Jean-Claude (June 1999). "Development of a new PCR-ribotyping method for based on ribosomal RNA gene sequencing". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 175 (2): 261–266. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13629.x. PMID 10386377.

- ^ Ala, Ugo; Piro, Rosario Michael; Grassi, Elena; Damasco, Christian; Silengo, Lorenzo; Oti, Martin; Provero, Paolo; Di Cunto, Ferdinando; Tucker-Kellogg, Greg (28 March 2008). "Prediction of Human Disease Genes by Human-Mouse Conserved Coexpression Analysis". PLOS Computational Biology. 4 (3) e1000043. Bibcode:2008PLSCB...4E0043A. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000043. PMC 2268251. PMID 18369433.

- ^ Pandey, U. B.; Nichols, C. D. (17 March 2011). "Human Disease Models in Drosophila melanogaster and the Role of the Fly in Therapeutic Drug Discovery". Pharmacological Reviews. 63 (2): 411–436. doi:10.1124/pr.110.003293. PMC 3082451. PMID 21415126.

- ^ Huang, Hui; Winter, Eitan E; Wang, Huajun; Weinstock, Keith G; Xing, Heming; Goodstadt, Leo; Stenson, Peter D; Cooper, David N; Smith, Douglas; Albà, M Mar; Ponting, Chris P; Fechtel, Kim (2004). "Evolutionary conservation and selection of human disease gene orthologs in the rat and mouse genomes". Genome Biology. 5 (7): R47. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-7-r47. PMC 463309. PMID 15239832.

- ^ Ge, Dongliang; Fellay, Jacques; Thompson, Alexander J.; Simon, Jason S.; Shianna, Kevin V.; Urban, Thomas J.; Heinzen, Erin L.; Qiu, Ping; Bertelsen, Arthur H.; Muir, Andrew J.; Sulkowski, Mark; McHutchison, John G.; Goldstein, David B. (16 August 2009). "Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance". Nature. 461 (7262): 399–401. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..399G. doi:10.1038/nature08309. PMID 19684573. S2CID 1707096.

- ^ Bertram, L. (2009). "Genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer's disease". Human Molecular Genetics. 18 (R2): R137 – R145. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp406. PMC 2758713. PMID 19808789.

- ^ Kellis, Manolis; Patterson, Nick; Endrizzi, Matthew; Birren, Bruce; Lander, Eric S. (15 May 2003). "Sequencing and comparison of yeast species to identify genes and regulatory elements". Nature. 423 (6937): 241–254. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..241K. doi:10.1038/nature01644. PMID 12748633. S2CID 1530261.

- ^ Marchler-Bauer, A.; Lu, S.; Anderson, J. B.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M. K.; DeWeese-Scott, C.; Fong, J. H.; Geer, L. Y.; Geer, R. C.; Gonzales, N. R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D. I.; Jackson, J. D.; Ke, Z.; Lanczycki, C. J.; Lu, F.; Marchler, G. H.; Mullokandov, M.; Omelchenko, M. V.; Robertson, C. L.; Song, J. S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R. A.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, N.; Zheng, C.; Bryant, S. H. (24 November 2010). "CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (Database): D225 – D229. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1189. PMC 3013737. PMID 21109532.

Conserved sequence

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Types

A conserved sequence refers to a segment of DNA, RNA, or protein that exhibits high similarity or remains relatively unchanged across distantly related species or evolutionary lineages, signifying preservation due to functional constraints that limit mutations.[5][6] These sequences are identified through comparative analyses showing minimal variation over millions of years, often indicating essential roles in cellular processes or organismal development.[5] The concept of conserved sequences was introduced in the 1960s, with advances in DNA sequencing techniques in the 1970s enabling the detection of invariant regions resistant to evolutionary change.[7][8] Conservation primarily occurs at the sequence level (primary structure), which often preserves higher-order structures such as secondary (e.g., alpha-helices or beta-sheets formed by hydrogen bonding) and tertiary (three-dimensional folds stabilized by hydrophobic interactions and disulfide bonds) in proteins.[9][10] In terms of length, short conserved motifs typically span 5-20 base pairs (bp) and often serve as regulatory elements, like transcription factor binding sites, while longer conserved domains exceed 100 bp and encompass functional units such as enzyme active sites.[11] Representative examples include the highly invariant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences essential for translation machinery across all domains of life and the Hox gene clusters, which maintain organizational similarity in animals to regulate body patterning.[12][13] Conservation also varies by evolutionary scale. Within a single species, conserved sequences display low polymorphism, reflecting strong purifying selection that suppresses genetic variation.[14] Between species, they appear in orthologous genes shared through common ancestry, such as core metabolic enzymes.[6] At the pan-genomic level, they form core genome elements present in all strains of a microbial species or across broader taxa, underpinning universal biological functions.[15]Biological Importance

Conserved sequences are preserved across species primarily due to functional constraints that render mutations deleterious to organismal fitness. In coding regions, mutations in highly conserved residues, such as those forming protein active sites, can abolish enzymatic activity or structural integrity, thereby disrupting vital cellular processes. Similarly, in non-coding regions, conservation maintains the integrity of regulatory elements like promoters and enhancers, which orchestrate precise gene expression patterns, as well as splicing signals essential for accurate mRNA processing. These constraints ensure that sequence variations are minimized in regions where even subtle changes could impair protein function or regulatory precision.[16][17][18] From an evolutionary perspective, the persistence of conserved sequences reflects ongoing purifying selection, where deleterious mutations are systematically eliminated from populations, resulting in low tolerance for variation in functionally critical genomic regions. This selective pressure facilitates the identification of essential genes and elements, as highly conserved loci are more likely to underpin core biological functions. For example, recent estimates suggest approximately 10-11% of the human genome exhibits evolutionary constraint and conservation (as of 2024), far exceeding the ~1.5-2% occupied by protein-coding sequences, highlighting the broad evolutionary importance of both coding and non-coding conserved elements. Recent whole-genome sequencing efforts (as of 2024-2025) continue to refine estimates of conserved regions using large-scale population data. Such patterns of conservation provide insights into adaptive fitness, as they indicate genomic features that have been refined over millions of years to support survival and reproduction.[19][20][21][22][23] Prominent examples illustrate the biological significance of these conserved sequences. The cytochrome c protein, central to mitochondrial electron transport, maintains over 60% amino acid identity across diverse eukaryotic species, from humans to yeast, reflecting its indispensable role in energy production and apoptosis regulation.[24] In developmental biology, conserved signaling pathways like Wnt exemplify how sequence preservation enables coordinated cell fate decisions; the core Wnt/β-catenin components are evolutionarily conserved from invertebrates to vertebrates, ensuring robust patterning during embryogenesis. These cases demonstrate how conservation safeguards mechanisms critical for cellular homeostasis and organismal development.[25] Metrics derived from comparative analyses further quantify the functional relevance of conserved sequences. For instance, regions exhibiting greater than 80% sequence identity over spans of 100 base pairs or more often correlate with essential regulatory or structural roles, serving as reliable proxies for inferring biological importance in genomic studies. These thresholds help prioritize sequences under strong selective pressure, aiding in the annotation of functional elements without exhaustive experimental validation.[26]Historical Development

Early Observations in Molecular Biology

The concept of conserved sequences emerged in the mid-20th century through comparative analyses of proteins and nucleic acids, revealing that certain molecular structures remained remarkably similar across diverse species, suggesting functional constraints on evolution. In 1962, Émile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling proposed the molecular clock hypothesis, positing that protein sequences evolve at approximately constant rates over time, with slower changes in functionally critical regions implying sequence conservation due to selective pressures.[27] This idea stemmed from their examination of hemoglobin variants, highlighting how essential amino acids were preserved while neutral positions varied, laying foundational groundwork for understanding evolutionary conservation in molecular biology. Early comparative sequencing of cytochrome c, starting with horse in 1961 and extending to multiple species by Emanuel Margoliash and colleagues in the mid-1960s, further demonstrated high sequence similarity across vertebrates and invertebrates, reinforcing the notion of conserved functional motifs in electron transport proteins.[28] Pioneering experiments in protein sequencing provided direct evidence of conservation in specific biomolecules. Vernon Ingram's 1957 work on sickle cell anemia demonstrated that normal and mutant human hemoglobins differed by a single amino acid substitution in a peptide chain, yet the overall core structure was highly conserved across vertebrate hemoglobins when compared manually via fingerprinting techniques. Similarly, in the 1970s, Carl Woese utilized partial sequencing of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to identify conserved structural elements shared among bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea, enabling the construction of a universal tree of life based on these invariant sequences that underpin ribosomal function. Early detection of conserved sequences relied on rudimentary tools like manual amino acid sequencing and nucleic acid hybridization methods. DNA-RNA hybridization techniques, developed in the early 1960s, allowed researchers to quantify sequence similarity by measuring the stability of hybrid molecules formed between DNA from one species and RNA from another.[29] Such approaches complemented protein comparisons by extending observations to nucleic acids without full sequencing capabilities. A key milestone was the recognition of extreme conservation in histones during the 1960s, as partial sequencing and amino acid composition analyses showed that these DNA-binding proteins exhibited near-identical sequences in species ranging from peas to humans, underscoring their indispensable role in chromatin packaging and establishing conservation as a marker of essential cellular components.[30]Key Advances in Genomics

The advent of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 1983 and the widespread adoption of Sanger sequencing during the 1980s and 1990s revolutionized the ability to perform large-scale genomic comparisons, shifting from manual cloning and restriction mapping to automated, high-throughput analysis of DNA sequences across species.[31] These technologies facilitated the sequencing of entire genes and small genomes, such as those of bacteria and viruses, enabling early alignments that highlighted conserved motifs in essential proteins like ribosomal RNA.[32] By the mid-1990s, PCR amplification combined with Sanger's chain-termination method had scaled up to support comparative studies, revealing patterns of sequence conservation in eukaryotic genomes that suggested functional constraints beyond coding regions.[33] The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 marked a pivotal milestone, providing a reference sequence that underscored the limited extent of coding conservation—approximately 1.5% of the human genome—while indicating higher conservation in non-coding regions through initial alignments with other vertebrates.[34] In the 2000s, the ENCODE project, launched in 2003, systematically mapped functional elements across the human genome, identifying thousands of conserved non-coding sequences that regulate gene expression and development, often preserved across distant species.[35] Concurrently, comparative genomics efforts, such as alignments between human and mouse genomes, demonstrated that around 40% of the human genome shares homologous sequences with the mouse, with enhanced conservation in regulatory elements beyond exons.[36] In recent years up to 2025, long-read sequencing technologies like PacBio's high-fidelity reads and Oxford Nanopore's ultra-long reads have improved genome assembly accuracy, particularly in repetitive and structurally complex regions, allowing the detection of previously elusive ultra-conserved elements spanning hundreds of kilobases.[37] AI-driven tools, exemplified by AlphaFold's 2021 release, have advanced predictions of protein structures from sequences, inferring conservation patterns in disordered regions where traditional sequence alignment falls short.[38] These developments have driven a broader impact, transitioning research from protein-centric analyses to comprehensive genome-wide perspectives, with initiatives like the Earth BioGenome Project—aiming to sequence all known eukaryotic species by around 2032—enabling pan-eukaryotic comparisons to uncover universal conserved sequences essential for life.[39][40]Mechanisms of Conservation

Conservation in Coding Regions

Coding regions, which encode proteins, exhibit high levels of sequence conservation due to the functional constraints imposed by the need to maintain protein structure, stability, and activity. Mutations in these sequences often lead to deleterious effects on the protein product, such as altered folding or loss of enzymatic function, resulting in purifying selection that eliminates harmful variants from populations. For example, orthologous genes between closely related vertebrates such as humans and mice typically show 70-90% sequence identity in their coding exons, reflecting this strong selective pressure to preserve essential biochemical properties.[41] A key mechanism driving this conservation is the distinction between synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions. Synonymous changes, which do not alter the amino acid sequence, occur at a higher rate than non-synonymous ones, as measured by the dN/dS ratio (where dN is the rate of non-synonymous substitutions and dS is the synonymous rate); values less than 1 indicate purifying selection favoring conservation of the protein sequence. This pattern is evident in comparisons of exons versus introns, where exons display significantly higher conservation (often 2-5 times greater nucleotide identity) due to their direct role in translation, while introns accumulate more neutral mutations. Additionally, codon usage bias contributes to conservation by favoring codons that optimize translation efficiency and accuracy, reducing the fitness cost of rare codons in highly expressed genes. Specific structural features within coding regions further amplify conservation. Functional domains, such as kinase domains in signaling proteins, are under intense selective pressure to remain invariant, as even single amino acid changes can disrupt phosphorylation activity critical for cellular regulation. Prominent examples include universally conserved ribosomal proteins, like RP S3, which is highly conserved across bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes due to its indispensable role in ribosome assembly and function, ensuring translational fidelity across all domains of life. Similarly, homeobox domains in developmental genes, such as those in the Hox gene family, maintain high sequence similarity (often >80% identity) to preserve DNA-binding specificity essential for embryonic patterning. These cases underscore how conservation in coding regions is tightly linked to the preservation of protein-level phenotypes vital for organismal survival.Conservation in Non-coding Regions

Non-coding regions of the genome, which constitute the majority of eukaryotic DNA, exhibit significant evolutionary conservation in specific functional elements essential for gene regulation and structural integrity. These conserved sequences often include promoters, enhancers, untranslated regions (UTRs), and intronic elements, where preservation across species indicates selective pressure against mutations that could disrupt regulatory processes. Unlike coding regions, conservation here primarily supports non-protein-coding functions, such as modulating transcription initiation, mRNA stability, and chromatin architecture.[42] Promoters harbor conserved transcription factor (TF) binding motifs, such as the TATA box, which is recognized by the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and facilitates assembly of the pre-initiation complex in eukaryotes. Enhancers, frequently comprising conserved non-coding elements (CNEs), act as distal regulatory sequences that loop to promoters to activate gene expression, particularly in developmental contexts. In UTRs, conserved microRNA (miRNA) binding sites in the 3' UTRs of mRNAs enable post-transcriptional repression by miRNAs, with seed-matching sequences (nucleotides 2-7 of the miRNA) showing preferential evolutionary conservation across vertebrates. Introns contain functional elements like conserved splice sites adhering to the universal GT-AG rule, where the GT dinucleotide at the 5' splice site and AG at the 3' splice site are nearly invariant in eukaryotic pre-mRNA splicing. Additionally, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) often feature conserved scaffolds that serve as platforms for protein complexes, contributing to gene regulation.[43][42][44][45][46] The primary reasons for conservation in these non-coding regions stem from their critical roles in gene regulation and chromatin organization. TF binding motifs like the TATA box are under strong purifying selection to maintain precise transcription control, while CNEs in enhancers preserve developmental gene expression patterns across vertebrates. lncRNAs and other non-coding elements provide structural scaffolds that organize chromatin domains, facilitating phase separation into nuclear condensates or recruiting chromatin-modifying complexes to specific loci, thereby influencing epigenetic states and genome architecture. These functions impose selective constraints, often stronger than in neutral non-coding DNA, ensuring functional integrity over evolutionary timescales.[43][42][47] In vertebrate genomes, CNEs exemplify this conservation, with sequences longer than 200 base pairs clustering near developmental genes, such as those encoding homeodomain transcription factors, and showing up to 70% identity across distant species. Approximately 3-5% of the human genome consists of such conserved non-coding elements, a subset of the broader non-coding DNA that experiences elevated selection pressure compared to neutrally evolving regions. These patterns underscore the functional significance of non-coding conservation in maintaining regulatory networks essential for organismal development and homeostasis.[42][22]Identification Methods

Sequence Alignment Approaches

Sequence alignment approaches form the foundational computational methods for identifying conserved sequences by comparing biological sequences, such as DNA, RNA, or proteins, to reveal regions of similarity that suggest evolutionary conservation. Pairwise alignment techniques, which compare two sequences at a time, were among the earliest developed and remain essential for detecting conserved motifs or domains. The Needleman-Wunsch algorithm, introduced in 1970, performs global alignment by finding the optimal alignment across the entire length of two sequences using dynamic programming, accounting for matches, mismatches, and gaps to maximize a similarity score. This method is particularly useful for aligning closely related sequences where conservation is expected throughout.[48] In contrast, the Smith-Waterman algorithm, developed in 1981, enables local alignment by identifying the highest-scoring subsequences between two sequences, allowing for the detection of conserved regions without requiring alignment of the full sequences. This approach is advantageous for distantly related sequences where only specific functional elements, such as protein active sites, are conserved. Both algorithms handle gaps—representing insertions or deletions (indels)—through affine gap penalties, but their computational complexity of O(nm) time and space, where n and m are sequence lengths, limits them to shorter sequences.[49] For analyzing conservation across multiple species or homologs, multiple sequence alignment (MSA) extends pairwise methods to three or more sequences, enabling the visualization of conserved blocks amid variations. Progressive alignment, a widely adopted heuristic, constructs the MSA by first aligning the most similar pairs using a guide tree derived from pairwise distances, then progressively incorporating remaining sequences while preserving prior alignments. ClustalW, released in 1994, exemplifies this approach with enhancements like sequence weighting and position-specific gap penalties to improve sensitivity for protein and nucleotide alignments. MUSCLE, introduced in 2004, refines progressive methods through iterative optimization, achieving higher accuracy and throughput by repeatedly adjusting the alignment to minimize errors from early decisions.[50] These MSA tools are applied to align orthologous genes across species, highlighting conserved regions that indicate functional importance, such as in phylogenetic studies where alignments reveal evolutionary patterns. For instance, alignments of vertebrate genomes in the UCSC Genome Browser's conservation tracks display conserved blocks as histograms of similarity scores, aiding researchers in pinpointing non-coding conserved elements. Challenges in these approaches include managing indels and variable sequence lengths, which can introduce alignment artifacts; progressive methods risk propagating early errors, whereas iterative refinements in tools like MUSCLE mitigate this but increase computational demands. These alignment techniques underpin homology detection in broader comparative analyses.[51][52] Recent advances as of 2025 have focused on scalability and integration of artificial intelligence for large-scale MSAs. For example, HAlign 4 (2024) enables rapid alignment of millions of sequences using hybrid strategies, improving throughput for metagenomic data.[53] Similarly, FAMSA2 (2025) provides high-accuracy protein alignments at unprecedented speeds, suitable for billion-sequence datasets.[54] Deep learning approaches like BetaAlign further enhance accuracy by training on simulated alignments to refine progressive methods.[55]Comparative Genomics and Homology

Comparative genomics leverages large-scale sequence comparisons across multiple species to identify conserved sequences, primarily through the detection of homology, which indicates shared evolutionary ancestry. Homology is categorized into orthologs and paralogs: orthologs arise from speciation events, retaining similar functions in different species due to vertical descent from a common ancestral gene, while paralogs result from gene duplication within a lineage, often leading to functional divergence.[56] Tools such as BLAST, introduced in 1990, enable rapid detection of homologous sequences by performing local alignments optimized for similarity scores, facilitating initial homology inference in comparative studies.[57] More advanced pipelines like OrthoMCL, developed in 2003, cluster proteins into orthologous groups using reciprocal best-hits and Markov clustering algorithms, distinguishing orthologs from paralogs across eukaryotic genomes.[58] Whole-genome alignments extend pairwise comparisons to reveal conserved regions amid genomic rearrangements. Methods like BLASTZ, from 2003, align human and mouse genomes by identifying high-scoring segment pairs, providing a foundation for detecting syntenic regions with conserved gene order. Mauve, introduced in 2004, supports multiple genome alignments while accounting for rearrangements, using seed-and-extend approaches to identify locally collinear blocks that preserve synteny, essential for tracing conserved sequences in bacterial and eukaryotic genomes.[59] Integrated pipelines such as Ensembl Compara automate cross-species alignments by combining pairwise tools with tree-based reconciliation, generating orthology predictions and multi-alignments for over 300 species, including vertebrates and invertebrates.[60] Key approaches in comparative genomics include phylogenetic hidden Markov models (phylo-HMMs) for scoring conservation and synteny-based block identification. PhastCons, a 2005 phylo-HMM method, analyzes multi-species alignments to compute per-base conservation probabilities, distinguishing neutrally evolving from conserved sites by modeling substitution rates along a phylogenetic tree.[61] Syntenic blocks, identified through tools like Mauve, highlight genomic segments with conserved order and content, aiding in the annotation of orthologous regions resistant to shuffling over evolutionary time. Advances in multi-species alignments have scaled comparisons dramatically, enhancing conserved sequence detection. The UCSC 100-way vertebrate alignment project, released in 2012, integrated genomes from 100 species using progressive alignment strategies, enabling phylo-HMM analyses that identified millions of conserved elements across diverse vertebrates.[62] By 2023, projects like Zoonomia expanded this to 240 mammalian genomes, producing whole-genome alignments via reference-free methods such as Progressive Cactus, which improved alignment coverage and accuracy for distant species, revealing novel conserved non-coding elements. These resources underpin homology-based inference, supporting functional predictions through shared sequence conservation.Statistical Scoring and Evaluation

Scoring systems for assessing conserved sequences in alignments rely on substitution matrices that quantify the likelihood of amino acid or nucleotide replacements based on evolutionary observations. The Point Accepted Mutation (PAM) matrices, developed by Dayhoff et al., model evolutionary changes over time by extrapolating from closely related protein sequences, where each matrix represents substitutions after a specified number of point accepted mutations per 100 residues.[63] Similarly, BLOSUM matrices, introduced by Henikoff and Henikoff, derive log-odds scores from conserved blocks in distantly related proteins, with BLOSUM62 being widely used for its balance between sensitivity and specificity in detecting moderate homology.[64] These matrices assign positive scores to conservative substitutions and negative scores to unlikely ones, enabling the computation of alignment scores as sums of pairwise substitution values. Gap penalties in sequence alignments account for insertions or deletions, which represent evolutionary indels, by subtracting costs from the total score to discourage excessive gaps while allowing biologically plausible ones. Common implementations include linear penalties proportional to gap length or affine penalties that charge a fixed opening cost plus an extension cost per residue, as formalized in dynamic programming algorithms for optimal alignments. These penalties are empirically tuned to reflect the relative rarity of indels compared to substitutions, ensuring that conserved regions are not artifactually fragmented. Statistical tests evaluate the significance of conservation by comparing observed alignments to null models of random sequences. In tools like BLAST, the E-value measures the expected number of alignments with scores at least as extreme by chance, derived from an extreme value distribution under a random model, where lower E-values (e.g., <10^{-5}) indicate significant homology. Conservation scores such as GERP (Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling) quantify constraint by estimating the number of rejected substitutions at each site relative to neutral expectations, with positive GERP scores signaling evolutionary conservation across multiple species alignments. Evaluation of conservation incorporates background models of neutral evolution rates to distinguish adaptive constraint from stochastic variation. Neutral rates are estimated from putatively unconstrained sites or fourfold degenerate codons, providing a baseline for expected substitutions under no selection. Bayesian methods, such as those in PhastCons, compute posterior probabilities of conservation at each site using hidden Markov models that integrate phylogenetic substitution rates and prior assumptions about conserved versus neutral states, yielding probabilities >0.9 for strongly conserved elements. Key formulas underpin these approaches. The log-odds score for a substitution in alignments is given bywhere is the observed probability of the pair in aligned sequences and is the expected probability under independence, often scaled in half-bit units for matrices like BLOSUM.[65] For coding regions, the dN/dS ratio assesses purifying selection as

with values <1 indicating conservation due to negative selection, as originally estimated via Jukes-Cantor-like corrections for multiple hits. Recent developments as of 2025 incorporate machine learning for enhanced evaluation, such as protein language models that identify conserved motifs in intrinsically disordered regions by analyzing evolutionary patterns in large datasets.[66]