Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

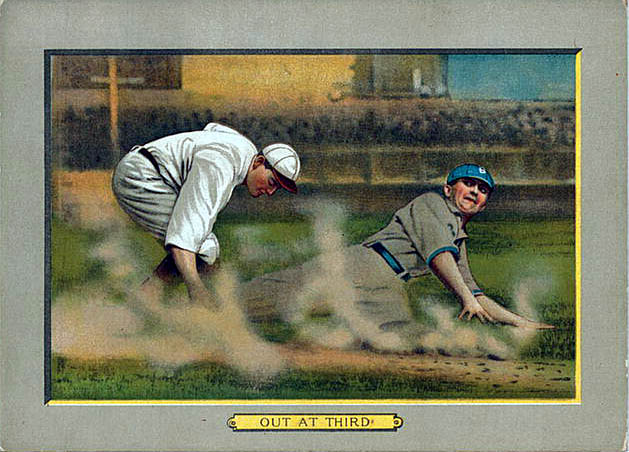

Out (baseball)

View on Wikipedia

In baseball, an out occurs when the umpire rules a batter or baserunner out. When a batter or runner is out, they lose their ability to score a run and must return to the dugout until their next turn at bat. When three outs are recorded in a half-inning, the batting team's turn expires.

To signal an out, an umpire generally makes a fist with one hand, and then flexes that arm either upward, particularly on pop flies, or forward, particularly on routine plays at first base. Home plate umpires often use a "punch-out" motion to signal a called strikeout.

Ways of making outs

[edit]- The most common ways batters or runners are put out are when:

- The batter strikes out (they make three batting mistakes, known as strikes, without hitting the ball into fair territory);

- The batter flies out (they hit the ball and it is caught before landing);

- A baserunner fails to return to their time-of-pitch base after a flyout occurs and a fielder with the ball touches the base (commonly known as "doubling off" or "doubling up", as this would constitute a double play);

- a baserunner is tagged out (they are touched by the ball, held in an opponent's hand, while not on a base);

- a baserunner is forced out (an opponent with the ball reaches the base the runner is forced to advance to before the runner does).

- The batter is out when:

- Strikeout-related outs:

- with two strikes, the batter swings at a pitched ball and misses;[1]

- with two strikes, they do not swing at a pitch that the umpire judges to be in the strike zone (and the catcher catches the ball and does not drop it);[1]

- with two strikes, the batter foul tips a pitch directly back into the catcher's mitt, and the catcher holds the ball and does not drop it;[2][3]: 5.09(a)(2)

- with two strikes, they bunt a pitch into foul territory;[1][3]: 5.09(a)(4)

- the third strike is pitched and caught in flight;[3]: 5.09(a)(1)

- on any third strike, if a baserunner is on first and there are fewer than two outs (even when not caught);[3]: 5.09(a)(3)

- Outs related to the batter's box:

- they are hit by their own fair ball, outside the batter's box, before the ball is played by a fielder;[3]: 5.09(a)(7)

- they hit a pitch while one foot is entirely outside the batter's box;

- they step from one batter's box to the other when the pitcher is ready to pitch;

- Other ways of being out:

- they commit interference;[3]: 5.09(a)(8–9)

- they fail to bat in their proper turn and is discovered in an appeal; or

- they are found to have used an altered bat.[3]: 6.03(a)(5)

- Strikeout-related outs:

- Ways that runners can be out:

- The batter-runner is out when:

- a preceding runner interferes with a fielder trying to complete a double play on the batter-runner;

- Tag-related outs:

- a fielder with a live ball in their possession touches first base or tags the batter-runner before the batter-runner reaches first base (except when the batter is awarded first base, such as on a base on balls)

- the batter-runner does not return directly to first base after overrunning the bag and they are tagged with the ball by a fielder.

- Flyout-related outs:

- a batted ball is caught in flight (fly out);

- they hit an infield popup while the infield fly rule applies;

- a fielder intentionally drops a line drive with fewer than two outs in a force situation (man on first, men on first and second, men on first and third, bases loaded) in an attempt to create a double play;

- Any baserunner, other than the batter-runner, is out when:

- they are forced out; that is, they fail to reach their force base before a fielder with a live ball touches that base;

- a fielder catches a batted ball in flight, and subsequently, some fielder with a live ball in possession touches the runner's time of pitch base before the runner returns to it (appeal play);

- while they are attempting to reach home plate with fewer than two outs, the batter interferes with a fielder and such action hinders a potential tag out near home plate;

- they are found to have committed a mockery of the game, for example, a stolen base of first from the second; or

- they are found to be an illegal substitute.

- Any baserunner, including the batter-runner, is out when:

- they are tagged out; that is, touched by a fielder's hand holding a live ball while in jeopardy, such as while not touching a base;

- they stray more than three feet (0.9 meters) from their running baseline in attempting to avoid a tag;

- they pass a base without touching it and a member of the defensive team properly executes a live ball appeal;

- they pass a preceding runner who is not out;

- they commit interference, such as when they contact a fielder playing a batted ball, or when they contact a live batted ball before it passes a fielder other than the pitcher;

- they are touched by a fair ball in fair territory before the ball has touched or passed an infielder. The ball is dead and no runner may score, nor runners advance, except runners forced to advance. EXCEPTION: If a runner is touching their base when touched by an infield fly, they are not out, although the batter is out;

- they intentionally abandon their effort to run the bases after touching first base; or

- they run the bases in reverse order in an attempt to confuse the defence or to make a travesty of the game.[3]: 5.09(b)(10)

- The batter-runner is out when:

Note: When a fielder makes a putout, they must maintain secure possession of the ball. The general exception is when a fielder loses possession of the ball because they attempt to throw it immediately after making the out.

Crediting outs

[edit]In baseball statistics, each out must be credited to exactly one defensive player, namely the player who was the direct cause of the out. When referring to outs credited to a defensive player, the term putout is used. Example: a batter hits a fair ball that is fielded by the shortstop. The shortstop then throws the ball to the first baseman. The first baseman then steps on first base before the batter reaches it. For this play, only the first baseman is credited with a putout, while the shortstop is credited with an assist. For a strikeout, the catcher is credited with a putout, because the batter is not out until the pitched ball is caught by the catcher. (If the catcher drops the third strike and has to throw the batter-runner out at the first base, the first baseman receives the putout while the catcher receives an assist.) When an out is recorded without a fielder's direct involvement, such as where a runner is hit by a batted ball, the fielder nearest to the action is usually credited with the putout.

Although pitchers seldom get credited with putouts, they are credited with their role in getting outs through various pitching statistics such as innings pitched (a measure of the number of outs made by the pitcher, used in calculating their ERA) and strikeouts.

Outs that occur in specific situations

[edit]Certain terms are sometimes used to better describe the circumstances under which an out occurred.

For strike outs:

- A strike out looking means that a third strike was called because the ball was in the strike zone

- A strikeout swinging refers to a swinging third strike.

For force outs and/or tag outs (outs that retire runners):

- Throw out: refers to when a throw is made to a fielder covering a base, who then uses the ball to put out a runner coming to that base.[4]

- Ground out: when the batter hits a ground ball that leads to them being thrown out.

For fly outs:

- Pop out: When the batter hits a pop up (a fly ball that goes high but not far) and it is caught.[5]

- Line out: A line drive that is caught.

- Foul out: A foul fly ball that is caught.

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Baseball Explained by Phillip Mahony, McFarland Books, 2014. See www.baseballexplained.com Archived August 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Baseball Explained by Phillip Mahony, McFarland Books, 2014. See www.baseball explained.com[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Official Baseball Rules 2017 Edition. United States of America: Office of the Commissioner of Baseball. 2017. ISBN 978-0-9961140-4-2. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "Rule 2 - Section 24 - OUT: FORCE-OUT, PUTOUT, STRIKEOUT, TAG OUT, THROW-OUT". Baseball Rules Academy. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Pop Out | A Baseball Term at Sports Pundit". www.sportspundit.com. Retrieved August 25, 2021.